Abstract

Background

Children living with HIV continue to be in urgent need of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART). Strategies to scale up and improve pediatric HIV care in resource-poor regions, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, require further research from these settings. We describe treatment outcomes in children treated in rural Uganda after 1 and 2 years of ART start.

Methods

Cross-sectional assessment of all children treated with ART for 12 (M12) and 24 (M24) months was performed. CD4 counts, HIV RNA levels, antiretroviral resistance patterns, and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) plasma concentrations were determined. Patient adherence and antiretroviral-related toxicity were assessed.

Results

Cohort probabilities of retention in care were 0.86 at both M12 and M24. At survey, 71 (83%, M12) and 32 (78%, M24) children remained on therapy, and 84% participated in the survey. At ART start, 39 (45%) were female; median age was 5 years. Median initial CD4 percent was 11% [IQR 9-15] in children < 5 years old (n = 12); CD4 count was 151 cells/mm3 [IQR 38-188] in those ≥ 5 years old (n = 26). At M12, median CD4 gains were 11% [IQR 10-14] in patients < 5 years old, and 206 cells/mm3 [IQR 98-348] in ≥ 5 years old. At M24, median CD4 gains were 11% [IQR 5-17] and 132 cells/mm3 [IQR 87-443], respectively. Viral suppression (< 400 copies/mL) was achieved in 59% (M12) and 33% (M24) of children. Antiretroviral resistance was found in 25% (M12) and 62% (M24) of children. Overall, 29% of patients had subtherapeutic NNRTI plasma concentrations.

Conclusions

After one year of therapy, satisfactory survival and immunological responses were observed, but nearly 1 in 4 children developed viral resistance and/or subtherapeutic plasma antiretroviral drug levels. Regular weight-adjustment dosing and strategies to reinforce and maintain ART adherence are essential to maximize duration of first-line therapy in children in resource-limited countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the progress made in the last few years, in 2009 only 356,400 of the estimated 2.5 million children currently infected with HIV were receiving combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries [1]. Ninety percent of children infected with HIV were living in sub-Saharan Africa and the ART coverage in this area was 26% [2]. In the absence of therapy, more than 50% of HIV-infected children die before the age of 2 years [3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to increase access to treatment and care and to monitor the effectiveness of therapy.

Comprehensive evaluations of the effectiveness of generic fixed-drug ART in children come mainly from studies conducted in high-income countries [4–8] and, to a lesser extent, from urban areas of resource-poor settings [9, 10]. Assessments conducted in rural, resource-limited settings, where programs face important challenges to provide pediatric HIV care, are needed to adapt and improve existing treatment strategies.

In this study, we evaluated pediatric care provision in an HIV/AIDS program in rural, northwestern Uganda. Specifically, we describe survival and program retention, and, among children alive and on ART, patient adherence to therapy and presence of antiretroviral (ARV)-related toxicity. Also presented are plasma non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) concentrations and CD4 and virological responses, including resistance patterns, observed in children with detectable HIV viral load.

Methods

Arua Hospital AIDS Care Project

The Arua Hospital AIDS Care Project in Arua, Uganda has provided free treatment and care to patients living with HIV/AIDS since July 2002. Eligibility criteria for ART, patient management, and treatment are based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for scaling up ART in resource-poor settings [11, 12].

Pediatric first-line ART doses are adapted to children's weight. At the time of the study, children weighing < 10 kg received pediatric syrups of zidovudine (AZT)-lamivudine (3TC)-nevirapine (NVP); those 10-24 kg, adult fixed-dose combination (FDC) Triviro (3TC-stavudine [d4T]-NVP) or Coviro (3TC-d4T) tablets divided in half; and those ≥ 25 kg, whole tablets of Triviro or Triomune (3TC-d4T-NVP). In case of drug intolerance to NVP, efavirenz (EFV) was used. Due to drug shortages of Coviro and Triviro, between May 2004 and May 2006 children weighting ≥10 kg were given either whole or half Triomune tablets according to body weight. Second-line therapy regimens combined didanosine (ddI)-boosted lopinavir (LPV/r) and either AZT or abacavir (ABC) [13].

Nurses or clinical officers monitored the children every 2 to 6 months to determine clinical stage and diagnosed and treated ARV-related toxicity or intercurrent diseases. CD4 testing was performed at initiation and every 6 months thereafter (every year after 2005). No routine viral load monitoring was performed. Adherence counseling focused on parent/caregiver education. No specialized child psychological support or specific training for pediatric clinical management was offered at that time.

Study Population

We retrospectively analyzed two observational cohorts of children treated with ART for 12 ± 2 months (M12 cohort) or 24 ± 2 months (M24 cohort). Children alive still followed on treatment were eligible to participate in the cross-sectional survey, conducted between November 2005 and May 2006.

Study Procedures

We used a standardized questionnaire to collect sociodemographic information, WHO clinical stage data, weight, height, ART information (history of ARV use before enrollment, date of therapy start and regimen, current regimen), reported clinical ARV intolerances (asthenia, lipodystrophy, or gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and neurological symptoms), presence of ARV-related morphological disorders, and adherence to treatment. Two indicators of adherence as reported by parents/caregivers were used: i) percentage of pills taken in the last 4 days (number of pills taken divided by the total number of pills prescribed during the previous 4 days); and ii) percentage of adherence during the last 30 days using a 6-point visual analogue scale (VAS; 0 meaning no medication taken, and 6 all medication taken). For both indicators, poor adherence was defined using a threshold of < 95% [11], moderate adherence as 95-99%, and good adherence as 100%.

Hemoglobin level, platelet count, neutrophil fraction, plasma creatinine level, and transaminase level were measured in the children. Proteinuria and glucosuria was also determined using a urine dipstick technique. Severity of laboratory-based ARV toxicity was graded according to WHO guidelines [14]. CD4 counts were measured using either semi-automated (Cyflow counter, Partec, Münster, Germany) or manual (Dynabead, Dynal Biotech SA, Compiègne, France) techniques. HIV RNA testing was quantified with the automated TaqMan real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay (limit of detection 400 copies/mL) [15].

Samples of children with virological failure (viral load ≥ 1,000 copies/mL) were tested for genotypic resistance. Resistance mutation determination was based on the International AIDS Society Resistance Testing-USA panel and resistant virus defined according to the French ANRS resistance algorithm (http://www.hivfrenchresistance.org) [16, 17]. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [18, 19] was used to determine NVP or EFV plasma concentrations in blood samples collected 12 hours after the last dose intake.

Signed informed consent was sought from all parents or legal caregivers. The study protocol was approved by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, the Ugandan AIDS Research Committee, and the Saint-Germain-en-Laye Hospital Consultative Ethics Committee, France.

Statistical Analysis

Weight-for-height nutritional Z-scores (WHZ) were calculated using WHO growth reference data for children and adolescents [20–22]. Normal NNRTI therapeutic ranges (4,000-8,000 ng/mL for NVP and 1,000-4,000 ng/mL for EFV) [23], were used to define three categories of plasma concentrations: low (below the lower therapeutic limit), normal (within the therapeutic range), and high (above the higher therapeutic limit). Immunological failure was defined according to WHO guidelines [24]: CD4 values < 15% in children of < 36 months, < 10% in the 36-59 month group, and < 100 cells/mm3 in those aged ≥ 5 years.

Children who missed their last appointment for 2 months or more were considered lost-to-follow-up (LFU). Probabilities of survival and care retention were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. Patient follow-up was right-censored at the date of the study visit, death, or last visit for children LFU or transferred to another program. All study data were double-entered and analyses performed in Stata 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

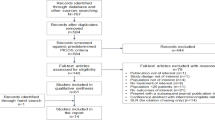

Eighty-seven children had initiated ART 12 ± 2 months (M12 cohort), and 41 children 24 ± 2 months (M24 cohort), before the study inclusion period (Figure 1). Overall, 6 children died, 11 were LFU, and 9 transferred to another program. A total of 102 children (80% of M12 and 79% of M24) were still alive and receiving ART. Of these, 59 (M12) and 27 (M24) children, respectively, participated in the cross-sectional survey (11 patients could not be found and 5 were screened too late).

Of the 6 recorded deaths before the survey, 4 occurred within 6 months of treatment start. Median time to death was 2.3 months [IQR 1.7-7.8]. Probabilities of care retention were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.85-0.95) at 6 months and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.79-0.91) at both 12 and 24 months. Probabilities of survival among children not LFU were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.91-0.99) at 6 months, and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.88-0.98) at both 12 and 24 months.

Characteristics at ART Initiation

At ART initiation, 39 (45.3%) of the children surveyed were female, median age was 5 years [IQR 3-8], and no children were aged < 12 months (Table 1). Fifty-one (59.3%) children were in clinical stage 3, and 14 (16.3%) in stage 4. Eighteen of 77 (23.4%) children had WHZ < -2. CD4 levels were measured in 38 children at ART initiation. Median CD4 measurement was 11% [IQR 9-15; n = 12] in children aged < 5 years and 151 cells/mm3 [IQR 38-188; n = 26] in children ≥ 5 years.

At therapy start, two children (2.3%) were ART-experienced (M12 cohort). Two others had received prevention of mother-to-child HIV infection prophylaxis, one patient received short-course AZT together with single-dose NVP (M12 cohort), and one patient received single-dose NVP (M24 cohort). Seventy (81.4%) children were started on AZT-3TC-NVP. A greater proportion of children had received ARV pediatric formulation in the M12 than in the M24 cohort (72.9% vs. 14.8%).

Characteristics at Survey

Mothers were the main caregivers for 50.8% of children in the M12 cohort but only for 37.0% in the M24 cohort (Table 2). Twenty-one percent of all children were orphans.

Using the 4-day recall adherence indicator, all children were classified as fully or moderately adherent to ART (Table 2). The 30-day VAS classified 14% (M12) and 11% (M24) of children, respectively, as poorly adherent to ART (< 95% score).

Gastrointestinal symptoms (43.0%) and peripheral neuropathy (38.4%) were the most frequently reported ARV-related toxicities. Morphological disorders were diagnosed in 20.9% (18/86) of children, including abdominal adipose tissue increase (15.1%, n = 13), lower limb muscle loss (4.7%, n = 4), gluteal muscle loss (3.5%, n = 3), breast adipose tissue increase (1.2%, n = 1), and facial muscle loss (1.2%, n = 1). Grade 1 or 2 neutropenia was the laboratory-related toxicity most frequently observed (16.3%), and severe toxicity was found in only one child (neutropenia of grade 3, M12).

Three children (11.1%) were in immunological failure at the time of the study; all were aged ≥ 5 years and received treatment for 2 years. In the M12 cohort, median CD4 percent gain was 11% [IQR 10-14; n = 10] in children aged < 5 years, and CD4 count gain 206 cells/mm3 [IQR 98-348; n = 11] in those of ≥ 5 years. In the M24 cohort, the CD4 percent gain was 11% [IQR 5-17; n = 2] in children aged < 5 years, and CD4 count gain 132 cells/mm3 [IQR 87-443; n = 15] in the elder group.

Plasma NNRTI Concentrations

Plasma concentrations of NNRTIs were measured in all children: 81 receiving NVP-based and 5 EFV-based therapy. Median prescribed NVP dose per body surface area was 150.3 mg/m2 [IQR 124.1-184.9] and decreased with increasing weight (Figure 2a). Subtherapeutic NNRTI plasma levels were detected in 32.2% (19/59) and 22.2% (6/27) of children at M12 and M24, respectively (Table 2). Only children weighing < 30 kg were found to be underdosed for NVP (37.0% of those who were prescribed 100 mg, 18.8% of those on 200 mg, and none of those on 25 mg of NVP twice daily; Figure 2b). Those weighing 20-30 kg were more frequently underdosed for NVP than other children (51.9% compared to 21.3% for children of < 10 kg; P = 0.005). Furthermore, 16.9% (10/59) of M12 and 7.4% (2/27) of M24 children had high plasma concentrations of NNRTIs (NVP or EFV).

Virological Response and Drug Resistance

HIV RNA suppression (< 400 copies/mL) was observed in 59.3% (35/59) of M12 and 33.3% (9/27) of M24 children (Table 3). Treatment adherence was not associated with either viral suppression (overall Fisher's exact P = 0.42 for VAS and 1.00 for 4-day recall) or presence of low NNRTI plasma concentrations (P = 0.35). Similarly, no association was observed between weight and viral suppression (P = 0.17), and, among children with detectable HIV RNA, weight was not correlated with viral load measurements (overall Spearman's correlation coefficient 0.07, and 0.05 for M12 only).

Genotypic resistance testing was successful in all 34 specimens with viral load ≥ 1,000 copies/mL (Table 3). HIV-1 subtypes were A1 (n = 7), C (n = 1), and D (n = 4), and for 22 children the subtype was not specified. Wild-type viruses were found in 4 patients (3 at M12 and 1 at M24). The most prevalent mutations were M184V (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTIs]) and Y181C (NNRTIs). Twenty-nine (85.3%) children had at least 1 major mutation conferring drug resistance to both NRTIs and NNRTIs. Prevalence of detectable resistant virus obtained after excluding the 8 children who had 400-999 HIV RNA copies/mL was 25% (13/52) at M12 and 62% (16/26) at M24. Twelve (M12) and 6 (M24) children had viruses resistant to both 3TC and NNRTIs (EFV and NVP). Eight specimens from the M24 cohort had K65R, T69A, V751, K103N, F116Y, Q151M, V179S, Y181C, and M184V mutations, conferring resistance to all NRTIs and to EFV and NVP.

Discussion

In these two pediatric cohorts of children followed in rural Uganda, we found retention rates of 86% and sustained immunological responses 1 and 2 years after ART start. Nevertheless, virological responses were suboptimal, as only 59% of M12 and 33% of M24 children achieved HIV viral suppression, and resistant viral strains were found in 25% and 62% of children, respectively.

As in other sub-Saharan African cohorts [25–28], all children followed in our program were enrolled and started therapy after the first year of life, median age at inclusion being 5 years old. Given that young, untreated children are at high risk of rapid disease progression and death before the age of 2 years [3, 29–32], the overall impact of HIV/AIDS programs in children living in these settings is likely to be suboptimal. Thus, delay in diagnosis of pediatric HIV infection and lack of availability of integrated HIV care and treatment in maternal and child health services at the time of the survey were likely to be partly responsible for the late start of therapy in our site.

Furthermore, as in other pediatric cohorts in resource-limited settings [26, 27, 33, 34], children in our program started therapy at advanced clinico-immunological stage and the majority of deaths and LFU occurred early in treatment. Delayed diagnosis of HIV infection and failure to diagnose and treat concurrent life-threatening infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, or sepsis [35] might be responsible for the early losses reported. Starting ART before 12 weeks of life has recently been associated with a 76% reduction in child mortality compared to deferred therapy until immunological or clinical progression is diagnosed [36]. Therefore, some of the early losses in our cohort could have been prevented if ART was started earlier. Despite this, we observed overall high and sustained survival and retention rates in children treated with ART up to 2 years after therapy start. These findings are consistent with reports from other programs from resource-limited settings [10, 25, 37].

Although direct comparison of immunological responses across studies is not possible because of its high dependence on patient age [38], we observed significant CD4 T-cell responses to ART independent of the virological status of the patient, and, as previously reported [27, 28, 38, 39], greater increases were seen in the first than in the second year of therapy among children aged ≥5 years (gains of 206 vs. 132 cells/mm3).

The small sample size in our survey must be considered when interpreting these findings. The small numbers of patients did not allow investigating risk factors for virological failure. Estimates reported in other studies range from 49% in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, to 80% in 63 children exposed to single-dose NVP in Durban, South Africa, at one year of therapy [9, 27, 40–42]. In the urban studies in Côte d'Ivoire and South Africa, 49% virological suppression was reported at 2 years of ART [9, 27]. Large differences in virological response rates have been observed between clinical studies among children, and the majority showed lower rates than in adults [38]. Possible explanations for such discrepancies could be differences in patient characteristics at ART initiation, regimens used, pediatric dose formulations, drug pharmacokinetics, and/or inadequate compliance to treatment.

As mentioned before, most children in our cohort started treatment at an advanced stage of disease. Presence of high HIV RNA at therapy start has been associated with slower decay rates of plasma viral levels and longer time to reach undetectable viral levels [42–45]. Increased risk of virological failure has also been reported in children with CD4 < 5% [40]. Our patients received NNRTI-based therapy, and most were given NVP. Higher rates of virological success have been shown in young patients treated with protease inhibitors than in those using NNRTI regimens in some [9] but not all studies [27, 46]. Furthermore, virological response has also been shown to vary in clinical studies using the same medication [38].

Ensuring adequate administration of ART to children is difficult and requires continuous dose adjustment in response to rapid changes in height and weight related to growth. In our cohorts, 1 in 4 children had subtherapeutic NVP plasma concentrations, especially children in the 20-30 kg weight range, highlighting the need for close monitoring of treatment, clear and simplified treatment guidelines, and availability of appropriate pediatric dose formulations.

Ensuring and maintaining good treatment adherence in children is also challenging, especially in resource-limited settings, since many children are orphans or live in difficult social situations: 1 in 5 patients were orphans in our study, and 43% had a caregiver other than a parent. Furthermore, palatable syrups or appropriate pediatric tablet formulations are expensive and not broadly available. In our study, 13% of children were identified as poorly adherent to ART, but this is likely to be underestimated since it was based on parental or caregiver reports. Four children with virological failure had wild-type virus and had therefore not been taking any treatment for some time. Furthermore, the prevalence of resistance mutations was relatively high but similar to those reported by a previous study in Côte d'Ivoire [26]. A recent review of studies investigating ART adherence in children treated in low- and middle-income countries identified difficult familial situations and low socioeconomic status, absence of parental and/or child HIV status disclosure, complicated regimens, and drug-related adverse events as barriers to treatment adherence [47, 48]. Age-adapted therapeutic education of children and extensive discussions and support to parents/caregivers need to be encouraged to improve ART uptake in this vulnerable group.

As reported by others [38, 49], we did not observe severe adverse drug reactions at the time of the survey, apart from one patient with severe neutropenia. However, 3 of 7 children reported gastrointestinal symptoms, which might interfere with drug absorption and affect treatment adherence [50]. Peripheral neuropathy and morphological disorders were not uncommon (38% and 21% of children, respectively). One longitudinal and one cross-sectional study also reported relatively high rates of lipodystrophy in children treated with d4T or protease inhibitors (29% and 33% of children, respectively), especially in those who started therapy at an advanced stage of disease [51, 52]. This syndrome is frequently associated with metabolic abnormalities such as hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia. However, its causal link to ART is to be established, and its long-term consequences for the treatment of children are unknown [52].

Conclusions

Important challenges need to be tackled to improve HIV pediatric care in resource-limited settings. These include increasing early HIV diagnosis through programs for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, training in pediatric clinical management and adherence counseling, and development of palatable and simplified pediatric drug formulations.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

abacabir

- ART:

-

combined antiretroviral therapy

- ARV:

-

antiretroviral

- AZT:

-

zidovudine

- d4T:

-

stavudine

- ddI:

-

didanosine

- EFV:

-

efavirenz

- FDC:

-

fixed-dose combination

- HPLC:

-

high performance liquid chromatography

- LFU:

-

lost to follow-up

- LPV/r:

-

boosted lopinavir with ritonavir

- NNRTI:

-

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NRTI:

-

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NVP:

-

nevirapine

- VAS:

-

visual analogue scale

- WHO:

-

the World Health Organization

- WHZ:

-

weight-for-height nutritional Z-scores.

References

UNICEF, UNAIDS, WHO, UNFPA and UNESCO: Children and AIDS: Fifth Stocktaking Report, 2010, Geneva, Switzerland. 2010

UNAIDS: Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010, Geneva, Switzerland. 2010

Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Serwadda D, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Sewankambo N, Kiduggavu M, Wawer M, Gray R: Mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected children of HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006, 41 (4): 504-508. 10.1097/01.qai.0000188122.15493.0a.

Chesney M: Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003, 17 (4): 169-177. 10.1089/108729103321619773.

Machado ES, Lambert JS, Afonso AO, Cunha SM, Oliveira RH, Tanuri A, Sill AM, Costa AJ, Soares MA: Alternative, age- and viral load-related routes of nelfinavir resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004, 23 (11): 1057-1059. 10.1097/01.inf.0000145874.88351.0f.

Eshleman SH, Jackson JB: Nevirapine resistance after single dose prophylaxis. AIDS Rev. 2002, 4 (2): 59-63.

Eshleman SH, Krogstad P, Jackson JB, Wang YG, Lee S, Wei LJ, Cunningham S, Wantman M, Wiznia A, Johnson G, Nachman S, Palumbo P: Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance in children receiving nucleoside analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors plus nevirapine, nelfinavir, or ritonavir (Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 377). J Infect Dis. 2001, 183 (12): 1732-1738. 10.1086/320728.

Fraaij PL, van Kampen JJ, Burger DM, de GR: Pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44 (9): 935-956. 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00004.

Jaspan HB, Berrisford AE, Boulle AM: Two-year outcomes of children on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and protease inhibitor regimens in a South african pediatric antiretroviral program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008, 27 (11): 993-998. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31817acf7b.

Reddi A, Leeper SC, Grobler AC, Geddes R, France KH, Dorse GL, Vlok WJ, Mntambo M, Thomas M, Nixon K, Holst HL, Karim QA, Rollins NC, Coovadia HM, Giddy J: Preliminary outcomes of a paediatric highly active antiretroviral therapy cohort from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Pediatr. 2007, 7: 13-10.1186/1471-2431-7-13.

Batallan A, Moreau G, Levine M, Longuet P, Bodard M, Matheron S: In utero exposure to Efavirenz: evaluation in children born alive. 2nd International AIDS Society Conference on HIV pathogenesis and treatment, Paris, France. 2003

Docze A, Benca G, Augustin A, Liska A, Beno P, Babela O, Krcmery V: Is antimicrobial multiresistance to antibiotics in Cambodian HIV-positive children related to prior antiretroviral or tuberculosis chemotherapy?. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004, 36 (10): 779-780.

Balkan S, Ciaffi L, Szumilin E: [Antiretroviral Treatment Protocol for Adults and Adolescents]. MSF-France (medical department), MSF-Suisse (medical department) (editors). 2006, Paris: Médecins Sans Frontières, 1-45.

WHO: HIV/AIDS Programme. Strengthening health services to fight HIV/AIDS. Antiretroviral Therapy For HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a public health approach. 2006 revision. Geneva. 2009

Rouet F: Transfer and evaluation of an automated, low-cost real-time reverse transcription-PCR test for diagnosis and monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in a West African resource-limited setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43 (6): 2709-2717. 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2709-2717.2005.

Descamps D: French national sentinel survey of antiretroviral drug resistance in patients with HIV-1 primary infection and in antiretroviral-naïve chronically infected patients in 2001-2002. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 38 (5): 545-552. 10.1097/01.qai.0000155201.51232.2e.

The French National Agency for AIDS Research AC11 Resistance group: HIV-1 Resistance group. HIV-1 genotypic drug resistance interpretation algorithms. 2005. 2007

Wu EY, Wilkinson JM, Naret DG, Daniels VL, Williams LJ, Khalil DA, Shetty BV: High-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of nelfinavir, a novel HIV-1 protease inhibitor, in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997, 695 (2): 373-380. 10.1016/S0378-4347(97)00193-X.

van Heeswijk RP, Hoetelmans RM, Meenhorst PL, Mulder JW, Beijnen JH: Rapid determination of nevirapine in human plasma by ion-pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1998, 713 (2): 395-399. 10.1016/S0378-4347(98)00217-5.

Dibley MJ, Staehling N, Nieburg P, Trowbridge FL: Interpretation of Z-score anthropometric indicators derived from the international growth reference. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987, 46 (5): 749-762.

Dibley MJ, Goldsby JB, Staehling NW, Trowbridge FL: Development of normalized curves for the international growth reference: historical and technical considerations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987, 46 (5): 736-748.

World Health Organization Working Group: Use and interpretation of anthropometric indicators of nutritional status. Bull World Health Organ. 1986, 64 (6): 929-941.

Taburet AM, Garrafo R, Goujard C, Molina M, Peytavin G, Treluyer JM: [Pharmacologie des Antirétroviraux: Indications des dosages plasmatiques des antirétroviraux]. Prise en charge médicale des personnes infectées par le VIH. Rapport 2006. Edited by: Flammarion SA, Direction Générale de la Sante, ANRS. 2006, Paris, 171-184.

World Health Organization: Switching an ARV Regimen in Infants and Children: Treatment Failure. Antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection in infants and children in resource-limited settings: towards universal access. Recommendations for a public health approach. 2006, Geneva, Switzerland, 44-49.

Fassinou P, Elenga N, Rouet F, Laguide R, Kouakoussui KA, Timite M, Blanche S, Msellati P: Highly active antiretroviral therapies among HIV-1-infected children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2004, 18 (14): 1905-1913. 10.1097/00002030-200409240-00006.

Chaix ML, Rouet F, Kouakoussui KA, Laguide R, Fassinou P, Montcho C, Blanche S, Rouzioux C, Msellati P: Genotypic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance in highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005, 24 (12): 1072-1076. 10.1097/01.inf.0000190413.88671.92.

Rouet F, Fassinou P, Inwoley A, Anaky MF, Kouakoussui A, Rouzioux C, Blanche S, Msellati P, ANRS 1244/1278 Programme Enfants Yopougon: Long-term survival and immuno-virological response of African HIV-1-infected children to highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens. AIDS. 2006, 20 (18): 2315-2319. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328010943b.

Sutcliffe CG, van Dijk JH, Bolton C, Persaud D, Moss WJ: Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008, 8 (8): 477-489. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70180-4.

Dunn D: Short-term risk of disease progression in HIV-1-infected children receiving no antiretroviral therapy or zidovudine monotherapy: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003, 362 (9396): 1605-1611.

Taha TE, Graham SM, Kumwenda NI, Broadhead RL, Hoover DR, Markakis D, van Der Hoever L, Liomba GN, Chiphangwi JD, Miotti PG: Morbidity among human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected and -uninfected African children. Pediatrics. 2000, 106 (6): E77-10.1542/peds.106.6.e77.

Spira R, Lepage P, Msellati P, Van De Perre P, Leroy V, Simonon A, Karita E, Dabis F: Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in children: a five-year prospective study in Rwanda. Mother-to-Child HIV-1 Transmission Study Group. Pediatrics. 1999, 104 (5): e56-10.1542/peds.104.5.e56.

Dabis F, Elenga N, Meda N, Leroy V, Viho I, Manigart O, Dequae-Merchadou L, Msellati P, Sombie I, DITRAME Study Group: 18-Month mortality and perinatal exposure to zidovudine in West Africa. AIDS. 2001, 15 (6): 771-779. 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00013.

Verweel G, van Rossum AM, Hartwig NG, Wolfs TF, Scherpbier HJ, de GR: Treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children is associated with a sustained effect on growth. Pediatrics. 2002, 109 (2): E25-10.1542/peds.109.2.e25.

Janssens B, Raleigh B, Soeung S, Akao K, Te V, Gupta J, Vun MC, Ford N, Nouhin J, Nerrienet E: Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive children: evaluation at 12 months in a routine programme in Cambodia. Pediatrics. 2007, 120 (5): 2006-3503.

Puthanakit T, Aurpibul L, Oberdorfer P, Akarathum N, Kanjananit S, Wannarit P, Sirisanthana T, Sirisanthana V: Hospitalization and mortality among HIV-infected children after receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 44 (4): 599-604. 10.1086/510489.

Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Steyn J, Madhi SA, Jean-Philippe P, McIntyre JA, CHER Study Team: Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359 (21): 2233-2244. 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971.

O'Brien DP, Sauvageot D, Zachariah R, Humblet P: In resource-limited settings good early outcomes can be achieved in children using adult fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006, 20 (15): 1955-1960. 10.1097/01.aids.0000247117.66585.ce.

van Rossum AM, Fraaij PL, de GR: Efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected children. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002, 2 (2): 93-102. 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00183-4.

Patel K, Hernan MA, Williams PL, Seeger JD, McIntosh K, Dyke RB, Seage GR, Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 219/219 Study Team: Long-term effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ cell evolution among children and adolescents infected with HIV: 5 years and counting. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46 (11): 1751-1760. 10.1086/587900.

Kamya MR, Mayanja-Kizza H, Kambugu A, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Semitala F, Mwebaze-Songa P, Castelnuovo B, Schaefer P, Spacek LA, Gasasira AF, Katabira E, Colebunders R, Quinn TC, Ronald A, Thomas DL, Kekitiinwa A, Academic Alliance for AIDS Care and Prevention in Africa: Predictors of long-term viral failure among ugandan children and adults treated with antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 46 (2): 187-193. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814278c0.

Adje-Toure C, Hanson DL, Talla-Nzussouo N, Borget MY, Kouadio LY, Tossou O, Fassinou P, Bissagnene E, Kadio A, Nolan ML, Nkengasong JN: Virologic and immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy and predictors of HIV type 1 drug resistance in children receiving treatment in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008, 24 (7): 911-917. 10.1089/aid.2007.0264.

Prendergast A, Mphatswe W, Tudor-Williams G, Rakgotho M, Pillay V, Thobakgale C, McCarthy N, Morris L, Walker BD, Goulder P: Early virological suppression with three-class antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected African infants. AIDS. 2008, 22 (11): 1333-1343. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830437df.

Spector SA, Hsia K, Yong FH, Cabral S, Fenton T, Fletcher CV, McNamara J, Mofenson LM, Starr SE: Patterns of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in infected children. J Infect Dis. 2000, 182 (6): 1769-1773. 10.1086/317621.

Starr SE, Fletcher CV, Spector SA, Yong FH, Fenton T, Brundage RC, Manion D, Ruiz N, Gersten M, Becker M, McNamaara J, Mofenson LM, Purdue L, Siminski S, Graham B, Kornhauser DM, Fiske W, Vincent C, Lischner HW, Dankner WM, Flynn PM: Combination therapy with efavirenz, nelfinavir, and nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 382 Team. N Engl J Med. 1999, 341 (25): 1874-1881. 10.1056/NEJM199912163412502.

Melvin AJ, Rodrigo AG, Mohan KM, Lewis PA, Manns-Arcuino L, Coombs RW, Mullins JI, Frenkel LM: HIV-1 dynamics in children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999, 20 (5): 468-473. 10.1097/00042560-199904150-00009.

Funk MB, Linde R, Wintergerst U, Notheis G, Hoffmann F, Schuster T, Kornhuber B, Ahrens P, Kreuz W: Preliminary experiences with triple therapy including nelfinavir and two reverse transcriptase inhibitors in previously untreated HIV-infected children. AIDS. 1999, 13 (13): 1653-1658. 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00008.

Vreeman RC, Wiehe SE, Ayaya SO, Musick BS, Nyandiko WM: Association of antiretroviral and clinic adherence with orphan status among HIV-infected children in Western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 49 (2): 163-170. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318183a996.

Vreeman RC, Wiehe SE, Pearce EC, Nyandiko WM: A systematic review of pediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008, 27 (8): 686-691. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816dd325.

Puthanakit T, Oberdorfer A, Akarathum N, Kanjanavanit S, Wannarit P, Sirisanthana T, Sirisanthana V: Efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children participating in Thailand's National Access to Antiretroviral Program. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41 (1): 100-107. 10.1086/430714.

da Silveira VL, Drachler ML, Leite JC, Pinheiro CA: Characteristics of HIV antiretroviral regimen and treatment adherence. Braz J Infect Dis. 2003, 7 (3): 194-201.

Arpadi SM, Cuff PA, Horlick M, Wang J, Kotler DP: Lipodystrophy in HIV-infected children is associated with high viral load and low CD4+ -lymphocyte count and CD4+ -lymphocyte percentage at baseline and use of protease inhibitors and stavudine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001, 27 (1): 30-34.

Jaquet D, Levine M, Ortega-Rodriguez E, Faye A, Polak M, Vilmer E, Lévy-Marchal C: Clinical and metabolic presentation of the lipodystrophic syndrome in HIV-infected children. AIDS. 2000, 14 (14): 2123-2128. 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00008.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/11/67/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their relatives for their participation in the study. They are also grateful to Robert Atayo, Helene Atizuyo, Hawa Avaru, Sylvester Awuta, Helene Chandiru, Jane Chandiru, Daniel Edemaga, William Hennequin, Emmanuel Kerukadho, Christopher Onzima, Lilian Osuru, and Ahmed Saadani for their field work, and Myrto Schaefer for technical assistance in the analysis and interpretation of results. The authors thank our partners in the Ministry of Health and MSF personnel working in Uganda for their support and collaboration. Thanks to Oliver Yun for his editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

LA designed and implemented the study, analyzed and managed data, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript. GG, PA, and CO set up and implemented the study in the field and contributed to the interpretations of results. LP prepared the study's EpiData database and performed data management. CR and A-MT performed the virological and genotypic testing and contributed to interpretation of these results. SB and DMO helped to design the study, interpret the results, and draft the manuscript. MP-R managed the data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted results, and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahoua, L., Guenther, G., Rouzioux, C. et al. Immunovirological response to combined antiretroviral therapy and drug resistance patterns in children: 1- and 2-year outcomes in rural Uganda. BMC Pediatr 11, 67 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-67

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-67