Abstract

Background

The DLX gene family encodes for homeobox transcription factors involved in the control of morphogenesis and tissue homeostasis. Their expression can be regulated by Endothelin1 (ET1), a peptide associated with breast cancer invasive phenotype. Deregulation of DLX gene expression was found in human solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. In particular, DLX4 overexpression represents a possible prognostic marker in ovarian cancer. We have investigated the role of DLX genes in human breast cancer progression.

Methods

MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma cells were grown in vitro or injected in nude mice, either subcutaneously, to mimic primary tumor growth, or intravenously, to mimic metastatic spreading. Expression of DLX2, DLX5 and DLX6 was assessed in cultured cells, either treated or not with ET1, tumors and metastases by RT-PCR. In situ hybridization was used to confirm DLX gene expression in primary tumors and in lung and bone metastases. The expression of DLX2 and DLX5 was evaluated in 408 primary human breast cancers examining the GSE1456 and GSE3494 microarray datasets. Kaplan-Meier estimates for disease-free survival were calculated for the patients grouped on the basis of DLX2/DLX5 expression.

Results

Before injection, or after subcutaneous growth, MDA-MB-231 cells expressed DLX2 but neither DLX5 nor DLX6. Instead, in bone and lung metastases resulting from intravenous injection we detected expression of DLX5/6 but not of DLX2, suggesting that DLX5/6 are activated during metastasis formation, and that their expression is alternative to that of DLX2. The in vitro treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with ET1, resulted in switch from DLX2 to DLX5 expression. By data mining in microarray datasets we found that expression of DLX2 occurred in 21.6% of patients, and was significantly correlated with prolonged disease-free survival and reduced incidence of relapse. Instead, DLX5 was expressed in a small subset of cases, 2.2% of total, displaying reduced disease-free survival and high incidence of relapse which was, however, non-significantly different from the other groups due to the small size of the DLX+ cohort. In all cases, we found mutually exclusive expression of DLX2 and DLX5.

Conclusions

Our studies indicate that DLX genes are involved in human breast cancer progression, and that DLX2 and DLX5 genes might serve as prognostic markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The abnormal expression of homeobox genes in many solid tumors and hematological malignancies [1, 2] has reinforced the notion that these key regulators of embryogenesis can also play a role in neoplastic processes. DLX genes, the vertebrate homologues of Drosophila distal-less (dll), constitute a family of homeobox transcription factors involved in control of cell differentiation and morphogenesis. The mouse and human DLX gene system is formed by three bi-gene clusters: DLX1 and DLX2; DLX5 and DLX6; DLX3 and DLX4. All DLX genes are expressed by embryonic stem cells and play a role in the control of craniofacial embryogenesis [3], of neurogenesis [4], and of formation of the distal regions of extending appendages [5]. Furthermore, DLX5 and DLX6 are expressed in all developing bones and control osteoblastogenesis and osteoblast/osteoclast coupling Although DLX genes are expressed in several adult tissues, including bone, brain and epithelia, little is known about their possible involvement in neoplastic process. We have previously demonstrated [6, 7] that Dlx genes participate to the regulatory cascade initiated by acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)-1 gene, a master regulator gene whose disruption is implicated in human acute leukemias [8]. DLX genes respond differently to the t(4;11)(q21;q23) chromosomal abnormality: while the expression of DLX2, DLX3, and DLX4 is virtually abrogated, that of DLX5 and DLX6 is increased [8]. These data indicate that different members of the DLX gene family could play diverse roles in predisposing cells to leukemic transformation. Furthermore, evidences have been found on DLX5 involvement in T-cell lymphomas both in mouse models and in humans [9].

In non-hematological malignancies most of the available information concerns DLX4. DLX4 overexpression by ovarian cancer is strongly associated with high tumor grade and advanced disease stage [10]. This gene, when overexpressed in the breast cancer cell line MCF7, inhibits apoptosis [11]. However, recently published microarray studies demonstrated the upregulation of DLX5 in several human solid tumors, suggesting that overexpression of DLX5 could contribute to tumor progression and represent a novel prognostic marker [12, 13]. The analysis of factors involved in Dlx gene regulation has evidenced that Endothelin1 (ET1) is directly involved in the activation of Dlx5 and Dlx6 and inhibits the expression of Dlx2 [14–16]. It is of note that ET1 expression has been directly associated to the invasive phenotype of breast tumor cells [17].

Methods

2.1. Cell culture and ET1 treatment

MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from Dr. Paola Manduca (Dipartimento di Oncologia, Biologia e Genetica, Università di Genova, Italy). Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 1% glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Biochrom Seromed, Berlin, Germany) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere.

For ET1 treatment, adherent sub-confluent MDA-MB-231 cells were starved for 24 h in serum-free medium, trypsinized and centrifuged. Pellets were resuspended in serum-free medium either containing or not 100 nM ET1 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); cells were then plated into a 12-well tissue culture plate and incubated for 8 h. Total RNA was then isolated from each well using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. All experiments were run in triplicate.

2.2. Animals

We used nude female mice of 5-6 weeks of age (Charles River, Calco, Italy) housed in laminar flow isolated hoods at the Animal Facility of the National Institute for Cancer Research in Genova. Housing and treatments of animals were in accordance with the Italian and European Community guidelines (D.L. 2711/92 No.116; 86/609/EEC Directive), and approved by the internal Ethic Committee.

2.3. Injection of MDA-MB-231 in mice

Sub-confluent MDA-MB-231 cells were trypsinized, resuspended in PBS and counted. Primary tumors were obtained by injecting 3 nude mice subcutaneously with 4 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells. Nodules developed within 2-3 weeks and were dissected when they reached an approximate volume of 250 mm3, generally within 1 month from injection. Metastases were obtained by injection of 2 × 105 cells in 100 μl of PBS in the left cardiac ventricle of 10 nude mice. Mice were sacrificed 2 months after cell inoculation and subjected to necropsy. Before sacrifice bone metastases were identified by radiography. Nodules and metastases were immediately processed for total RNA extraction or paraffin embedding.

2.4. Human samples

We examined normal breast tissues from 2 women undergoing reductive mammoplastic and primary breast cancer tissues from 2 patients undergoing curative surgery, one for invasive ductal carcinoma and one for invasive mixed carcinoma. Samples were kindly provided by Dr. L. Mastracci (Dipartimento di Discipline Chirurgiche, Anestesiologiche, Morfologiche e Metodologie Integrate, Università di Genova, Italy), through the GTB (Genoa Tissue Bank). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and approved by the S. Martino Hospital's Ethical Committee, Genova, Italy. This investigation conformed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. DLX2 and DLX5 expression was investigated by RT-PCR.

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

All bones (hindlimbs, ribs and tail) were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PAF) at 4°C, washed in PBS, decalcified for 18-24 hrs in Osteodec (Bio-Optica, Milano, Italy) and embedded in paraffin. All other organs were fixed in 4% PAF at 4°C, washed in PBS and embedded in paraffin. For immunohistochemistry staining, de-waxed sections were treated in microwave oven for 15 min in 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 and incubated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min. After 1 hr in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum in PBS), sections were incubated for 40 min at room temperature with either a rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki67 (1:250) or a mouse monoclonal anti-Keratin 18 (K18) Ab-8 clone L2A1 (1:100) (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA). After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary biotinylated antibody (BIO-SPA, Milano, Italy) for 30 min at room temperature followed by 10 min incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (BIO-SPA). HRP enzymatic activity was then revealed with diaminobenzidine (DAB).

2.6. In situ hybridization

8 μm sections were de-waxed, rehydrated, incubated in 10 μg/ml Proteinase K for 20 min at 37°C, and fixed with 4% PAF for 15 min at room temperature (RT). After washing in PBS, slides were incubated for 10 min in 0.2 M triethanolamine and 0.25% acetic anhydride, washed with PBS and incubated 15 min in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100. After washing, sections were prehybridized in 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 5X Denhardt's solution, 0.25 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 0.5 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA (all from Sigma). Overnight hybridization was performed at 60°C in prehybridization buffer containing 0.5 μg/ml probe. Dlx5 and Dlx6 probes were kindly provided by Dr. Giorgio Merlo (Università di Torino, Italy). Slides were washed in 5X SSC 5 min at 60°C, 1 hr at 60°C with 0.2 XSSC, 5 min in 0.2X SSC at RT and then incubated for 1 hr with blocking solution containing 10% goat serum in 0.1 M Tris pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl at RT in a humidified chamber. Alkaline Phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche Biochemicals, Basel, Switzerland) in blocking solution was then added to slides and incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Finally slides were washed in a solution containing 0.1 M Tris pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, equilibrated 5 min in a solution containing 0.1% Tween 20, 0.1 M Tris pH 9.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.05 M MgCl2, 1 mM levamisole and stained with BMPurple (Roche). Negative controls were run in parallel using sense probes.

2.7. RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 70-80% confluent MDA-MB-231 cells and from human and murine tissue samples using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription of 1 μg of DNase I-treated total RNA was performed using a Mo-MLV RNase-H(-) RT (Promega, Madison, WI) in a reaction volume of 20 μl. Resulting cDNA was then diluted by addition of 30 μl of water to reach a final volume of 50 μl and a concentration of cDNA 10×. Two μl of cDNA were used for amplification using TaqDNA polymerase (TibMolBiol, Genova, Italy).

The following primers were used:

human DLX5 sense 5'-ACCATCCGTCTCAGGAATCG

human DLX5 antisense 5'-ACCTTCTCTGTAATGCGGCC

human DLX6 sense 5'-GAACTGGCAGCTTCCTTA

human DLX6 antisense 5'-ACCAGTGAGAATAGCCAG

human DLX2 sense 5'-CTCTGCCTGCCTCATAAGG

human DLX2 antisense 5'-ATCGTAAGAACAGCGCAACC

human G3PDH sense 5'-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT

human G3PDH antisense 5'-TGGTTTCCGGACTTTCTTTG

murine β-actin sense 5'-TCGTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCAC

murine β-actin antisense 5'-TGGCCTTAGGGTTCAGGGGG.

The primers used for RT-PCR where specific for the human DLX genes and did not recognize mouse Dlxs. Annealing temperature was set to 60°C in all case, using 25 cycles for G3PDH and β-actin, and 35 cycles for the other genes.

2.8. Microarray data analysis

Expression analyses of human breast cancers were performed on the dataset GSE1456 [17] and GSE3494 [18] obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo. The data sets consists of 159 and 249 breast cancers from unselected consecutive patients who received surgery at Karolinska Hospital from 1994-1996 or at the Uppsala County Hospital from 1987-1989, respectively. Expression sets were calculated from raw microarray of the two combined datasets using the GCRMA algorithms implemented in Bioconductor [19]. The threshold level of positive gene expression was set to five on the log2-scale [20]. GeneSpring 7.1 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) software was used for visualization of expression data. Samples were clustered according to the expression of DLX2 and DLX5 to enhance visual interpretation by hierarchical clustering with average linkage. Kaplan-Meier curves for disease-free survival were calculated using the package "survival" of Bioconductor [19].

Results

3.1. DLX5, DLX6 and DLX2 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells, primary tumors and metastasis

To analyze the role of DLX2, DLX5, and DLX6 in breast primary tumor and metastasis formation, we used an experimental model of breast cancer metastasis. The MDA-MB-231 human mammary carcinoma cell line gives rise to metastases in several organs, including bones, when inoculated into the left cardiac ventricle of immunocompromised mice [21]. Instead, when MDA-MB-231 cells are injected subcutaneously, a nodule grows at the site of injection, without significant metastatic spreading [22]. We first analyzed the expression of DLX genes by RT-PCR in MDA-MB-231 cells in sub-confluent culture, the same cell density used for in vivo experiments. We found that cells express DLX2, but neither DLX5 nor DLX6 (Figure 1). Then, to assess DLX gene expression in primary tumors, we injected MDA-MB-231 cells subcutaneously in nude mice. By RT-PCR analysis we found that subcutaneous nodules were positive for DLX2, but neither for DLX5 nor for DLX6, as the in vitro cultured cell line (Figure 1). Instead, a different expression pattern was found when the expression of DLX2, DLX5, and DLX6 was checked in lung and bone metastases growing from MDA-MB-231 cells injected into the left cardiac ventricle. Expression of DLX5 and DLX6, but not of DLX2, was found by RT-PCR in lung metastases, a result opposite to that obtained in cultured cells and subcutaneous nodules, suggesting that activation of DLX5/6 and suppression of DLX2 had taken place during metastasis formation (Figure 1). To obtain a confirmation, we analyzed by in situ hybridization the expression of DLX5 and DLX6 on tissue sections of lung and bone metastases. Metastases showed high levels of DLX5 and DLX6 expression (Figures 2B, C and 3D, E). It is interesting to note that in situ hybridization on bone metastases showed an increased DLX5/6 expression signal intensity in tumor cells in close contact with the bone tissue, suggesting a correlation between expression of these genes and the invasion front. DLX5 and DLX6 signals co-localized with that of human K18, identified by immunohistochemistry with a human-specific antibody not cross-reacting with mouse, confirming that DLX-expressing cells were indeed of human origin (Figure 3G). To assess if DLX5/6 expression was related to cell proliferation, sections adjacent to those used for hybridization were stained with an anti-Ki67 antibody that specifically identifies actively proliferating cells. We could not find any clear correlation between the staining obtained with in situ hybridization and the location of Ki67-positive nuclei (Figure 3F). Confirming the results obtained by RT-PCR, no expression of DLX5 or DLX6 was found in subcutaneous nodules (Figure 3B, C).

Expression of DLX2 , DLX5 and DLX6 in MDA-MB231 cells in vitro and in vivo. The pattern of expression of DLX2, 5 and 6 in cultured MDA-MB-231 cells paralleled that observed in nodules resulting from subcutaneous injection into nude mice: a strong DLX2 expression was found, while neither DLX5 nor DLX6 were present. Lung metastases generated by injection of MDA-MB-231 into the left cardiac ventricle of nude mice displayed the opposite pattern of expression, with undetectable levels of DLX2 and high levels of DLX5 and 6.

In situ hybridization for DLX5 and DLX6 in MDA-MB-231 bone metastases. (A) A bone metastasis, visualized by radiography. (B and C) In-situ hybridization on sections of long bones containing MDA-MB-231 metastases showing high expression of DLX5 and DLX6. The signal was more intense at the invasion front (arrows). bn, cortical bone; met, metastasis.

In situ hybridization for DLX5 and DLX6 in MDA-MB-231 lung metastases and subcutaneous nodules. (A and C) Expression of DLX5 and DLX6 analyzed by in situ hybridization on sections of nodules derived by subcutaneous injection of MDA-MB231 cells in nude mice or (D and E) in sections of lung metastases derived from intracardiac injection of the same cells. (F) The proliferative state of the metastases was evidenced by Ki67 immunostaining. (G) K18 immunostaining of metastases was used to specifically identify human cells.

3.2. ET1 treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells induces DLX2 to DLX5 switch

During embryonic development ET1 plays a central role in the control of Dlx gene expression. In particular ET1 signaling is necessary and sufficient for the activation of Dlx5 in the mandibular arch [14, 16]. ET1 expression has been directly associated to the invasive phenotype of breast tumor cells in mouse models, but cultured MDA-MB-231 cells do not express ET1 [23]. To test whether ET1 signaling could be at the origin of the switch in DLX gene expression observed during metastasis formation, starved MDA-MB-231 cells where treated with ET1. We observed a clear reduction of DLX2 expression, paralleled by induction of DLX5 (Figure 4), suggesting that ET1 signaling could be involved in the DLX2 to DLX5 switch observed in metastases.

ET1 treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells induces DLX2 to DLX5 switch. Expression of DLX2 and DLX5 expression in of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with ET1. Subconfluent cultures were serum-starved and treated with vehicle alone (-) or ET1. RT-PCR analysis for DLX2, DLX5 and G3PDH was performed on total RNA isolated from individual wells.

3.3. DLX2 expression in human breast cancer is positively associated with disease-free survival

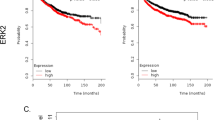

In order to assess the role of DLX2 and DLX5 gene expression also in humans, we performed a preliminary analysis of the DLX status on 2 samples of normal breast tissue and on 2 samples of primary breast tumor. Normal breast tissues expressed DLX2 but not DLX5. Instead, the two cases of mammary carcinoma were positive for DLX5, but negative for DLX2 (Figure 5A). These preliminary findings indicate that in humans, as in mice, expression of DLX5 could be related to metastatic capacity. To confirm this hypothesis, we analyzed the expression of DLX genes in a dataset of 408 cases of human breast cancers obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus, and correlated results with disease-free survival and relapse. In mammary tumors, the expression levels of DLX1, DLX3, DLX4 and DLX6 did not significantly differ from those observed in normal tissue (data not shown). Instead, DLX2 was expressed in 21.6% (88/408) of the tumors, while DLX5 expression was present in only 2.2% (9/408) of the tumors (Figure 5B). In all cases expression of the two genes was mutually exclusive, in no instance co-expression of DLX2 and DLX5 was observed. Patients were then divided into three groups, i.e. DLX2+/DLX5-, DXL2-/DLX5+ and DLX2-/DLX5-, and disease-free survival and relapse were assessed. The DLX2+/DLX5- patients had the longest average disease-free survival, whilst the DLX2-/DLX5+ patients had the shortest one. Kaplan-Meier analysis of disease-free survival showed a significant difference between the DLX2+/DLX5- and DLX2-/DLX5- groups (p = 0.018), however, the very small size of the DLX2-/DLX5+ sample resulted in non-significant difference when comparing this group of patients with either the DLX2+/DLX5- or the DLX5/2- groups (Figure 5C and 5D). Taking into account the age of patients as a co-variant did not modify these results.

DLX2 and DLX5 expression and correlation with disease-free survival in human breast cancers. (A) DLX2 and DLX5 expression were analyzed by RT-PCR in normal breast tissue (lane 1), ductal breast carcinoma (lane 2), and mixed breast carcinoma (lane 3). (B) Relative expression of DLX2 and DLX5 in 408 human breast cancer samples as analyzed by microarrays (Gene Expression Omnibus datasets GSE1459 and GSE3494). Expression values are color-coded, red: expression above the mean value, green: expression below the mean value. Intensity of colour correlates to the strength of up- or downregulation. Samples are ordered by hierarchical clustering based on the expression values of these two genes. Incidence of relapse is indicated in the lower bar (brown: no relapse, pink: relapse; 12 year follow-up). (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates of disease free survival of DLX2+/DLX5- patients (n = 88), DLX2-/DLX5- patients (n = 311), and DLX2-/DLX5+ patients (n = 9). (D) Statistical analysis of relapse incidence among the three groups. The incidence of relapse was 18/88 for DLX2+/DLX5- patients, 106/311 for DLX2-/DLX5- patients, and 5/9 for DLX2-/DLX5+ patients. P = p-value, RR = relative risk, OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Several homeobox genes are deregulated in a variety human tumors, and their deregulation appears to enhance cell survival and proliferation and to inhibit differentiation [2]. Among the DLX family of homeobox-containing genes, BP1, an isoform of DLX4, was found to correlate with poor prognosis in human breast cancer [24]. In the present study we specifically investigated the involvement of DLX2 and DLX5/6 in breast tumor progression.

In our mouse model, we found that DLX5 and DLX6, not expressed by MDA-MB-231 cells either cultured or grown subcutaneously, were specifically induced in metastases growing in bone or lung. On the contrary, DLX2 was expressed in cultured cells and in subcutaneous nodules, but not in bone or lung metastases. These results indicate that transition to metastatic phenotype is characterized by inhibition of DLX2 and induction of DLX5/6 expression. The expression of DLX5/6 in metastases of different tissues suggests that this phenomenon is independent from the microenvironment present at the site of metastasis formation. The lack of relationship with Ki67 expression indicates that in this model the expression of DLX5/6 is independent also from cell proliferation, though previous data indicated that Dlx5 contributes to increased cell proliferation in mouse thymic lymphomas [9].

A preliminary analysis on human samples showed inhibition of DLX2 and induction of DLX5 expression in breast cancer, as compared with normal breast tissue. Furthermore, analysis of microarray data on human breast tumors showed that breast cancer patients with DLX2 expression had on average better prognosis and less incidence of relapse, while DLX5 expression and DLX2 downregulation, was related to a subset of more aggressive tumors. In the data set we examined BP1 had not been studied, so we cannot confirm the previous finding of a relationship between the expression of this gene and poor prognosis in human breast cancer [24]. As in mice, shift from DLX2 to DLX5 expression seems to be related to progression toward an increasingly malignant phenotype. However, DLX5 expression in human breast tumors is not associated with expression of DLX6. This is not surprising: also in human lymphomas upregulation of DLX5 occurs without accompanying up-regulation of DLX6 [9].

We suggest that the alternative expression of DLX2 and DLX5 might be considered as markers of better and worse prognosis. It has to be noted that also in primary lung tumors DLX5 expression is associated with poor prognosis [25]. Both in our model system and in human tumors, the expressions of DLX5 and DLX2 were mutually exclusive, in agreement with other experimental data demonstrating that these genes reciprocally downregulate their expression in different territories [26, 27]. The opposite expression pattern of DLX2 and DLX5 in tumors are also consistent with previous observations, showing that DLX2 is expressed at higher levels in tumor cell lines which are more sensitive to apoptotic induction by fenretinide, whereas DLX5 and DLX6 appear to segregate in a distinct functional compartment [28]. The involvement of ET1 signaling could be at the origin of this switch in DLX gene expression. Indeed, ET-1 plays a role in breast cancer progression: it is associated with invading regions of tumors and is more common in tumors with high histological grade and lymph node invasion [29]. Furthermore, serum ET-1 is increased in patients with lymph node metastases, compared to those with no lymph node involvement. On these bases, ET-1 receptor antagonists have been used to prevent metastatic spreading in animal tumor models [30, 31]. However, clinical trials so far have failed to demonstrate a therapeutical effect of this class of drugs in human solid tumors [31, 32]. Not surprisingly, ET-1 was not independently predictive or relapse-free and overall survival in breast cancer [33] and, in the dataset we used ET1 is broadly present. Indeed, ET-1 induction could occur at the site of metastases and not of primary tumors.

Conclusions

Herein we show that a DLX2-to-DLX5/6 switch in gene expression occurs during metastasis formation by MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma cells injected into nude mice. This switch also occurs in vitro by treating MDA-MB-231 cells with ET1. In breast carcinoma patients, DLX2 expression is associated with increased disease-free survival, while expression of DLX5 is present in a small number of particularly aggressive cases. Expressions of DLX2 and DLX5 are mutually exclusive. Our data suggest that DLX2 and DLX5 are involved in human breast cancer progression, and that they might serve as good or poor prognostic markers, respectively. In particular DLX5 overexpression, together with concomitant DLX2 downregulation, could identify a subset of more aggressive cancers that would need a different treatment and a more careful follow-up. We suggest considering DLX2 and DLX5 as potential prognostic markers, provided that our results are confirmed in a different and broader cohort of patients.

References

Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK: Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2007, 26: 6766-6776. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210760.

Samuel S, Naora H: Homeobox gene expression in cancer: insights from developmental regulation and deregulation. European Journal of Cancer. 2005, 41: 2428-2437. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.014.

Beverdam A, Merlo GR, Paleari L, Mantero S, Genova F, Barbieri O, Janvier P, Levi G: Jaw transformation with gain of symmetry after Dlx5/Dlx6 inactivation: mirror of the past?. Genesis. 2002, 34: 221-227. 10.1002/gene.10156.

Perera M, Merlo GR, Verardo S, Paleari L, Corte G, Levi G: Defective neuronogenesis in the absence of Dlx5. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004, 25: 153-161. 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.004.

Merlo GR, Zerega B, Paleari L, Trombino S, Mantero S, Levi G: Multiple functions of Dlx genes. Int J Dev Biol. 2000, 44: 619-626.

Samee N, de Vernejoul MC, Levi G: Role of DLX regulatory proteins in osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2007, 17: 173-186.

Samee N, Geoffroy V, Marty C, Schiltz C, Vieux-Rochas M, Levi G, de Vernejoul MC: Dlx5, a positive regulator of osteoblastogenesis, is essential for osteoblast-osteoclast coupling. Am J Pathol. 2008, 173: 773-780.

Ferrari N, Palmisano GL, Paleari L, Basso G, Mangioni M, Fidanza V, Albini A, Croce CM, Levi G, Brigati C: DLX genes as targets of ALL-1: DLX 2,3,4 down-regulation in t(4;11) acute lymphoblastic leukemias. J Leukoc Biol. 2003, 74: 302-305. 10.1189/jlb.1102581.

Tan Y, Timakhov RA, Rao M, A AD, Xu J, Liu Z, Gao Q, Janwar SC, Di Cristofano A, Wiest DL, et al: A Novel Recurrent Chromosomal Inversion Implicates the Homeobox Gene Dlx5 in T-Cell Lymphoma from Lck-Akt2 Transgenic Mice. Cancer Research. 2008, 68: 1296-1302. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3218.

Hara F, Samuel S, Liu J, Rosen D, Langley RR, Naora H: A homeobox gene related to Drosophila distal-less promotes ovarian tumorigenicity by inducing expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2. Am J Pathol. 2007, 170: 1594-1606. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061025.

Stevenson HS, Fu SW, Pinzone JJ, Rheey J, Simmens SJ, PE B: BP1 transcriptionally activates bcl-2 and inhibits TNFalpha-induced cell death in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research. 2007, 9: R60-10.1186/bcr1766.

Pedersen N, Mortensen S, Sorensen SB, Pedersen MW, Rieneck K, Bovin LF, Poulsen HS: Transcriptional Gene Expression Profiling of Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Cancer Research. 2003, 63: 1943-1953.

Maxwell GL, Chandramouli GV, Dainty L, Litzi TJ, Berchuck A, Barrett JC, Risinger JI: Microarray analysis of endometrial carcinomas and mixed mullerian tumors reveals distinct gene expression profiles associated with different histologic types of uterine cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005, 11: 4056-4066. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2001.

Sato T, Kurihara Y, Asai R, Kawamura Y, Tonami K, Uchijima Y, Heude E, Ekker M, Levi G, Kurihara H: An endothelin-1 switch specifies maxillomandibular identity. Proceeding of the national Academy of Science USA. 2008, 105: 18806-18811. 10.1073/pnas.0807345105.

Ozeki H, Kurihara Y, Tonami K, Watatani S, Kurihara H: Endothelin-1 regulates the dorsoventral branchial arch patterning in mice. Mech Dev. 2004, 121: 387-395. 10.1016/j.mod.2004.02.002.

Charité J, McFadden DG, Merlo GR, Levi G, Clouthier DE, Yanagisaw M, Richardson JA, Olson EN: Role of Dlx6 in regulation of an endothelin-1-dependent, dHAND branchial arch enhancer. Genes Dev. 2001, 15: 3039-3049. 10.1101/gad.931701.

Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, Vega VB, Vergara L, Ploner A, Pawitan Y, Hall P, Klaar S, Liu ET, Bergh J: An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 13550-13555. 10.1073/pnas.0506230102.

Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP: Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31: e15-10.1093/nar/gng015.

Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al: Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004, 5: R80-10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80.

Chelly J, Concordet J, Kaplan J, Kahn A: Illegitimate transcription: transcription of any gene in any cell type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989, 86: 2617-2621. 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2617.

Sasaki A, Boyce BF, Story B, Wright KR, Chapman M, Boyce R, Mundy GR, Yoneda T: Biphosphonate risedronate reduces metastatic human breast cancer burden in bone in nude mice. Cancer research. 1995, 55: 3551-3557.

Price JE, Polyzos A, Zhang RD, Daniels LM: Tumorigenicity and metastases of human breast carcinoma cell lines in nude mice. Cancer Research. 1990, 50: 717-721.

Yin JJ, Mohammad KS, Käkönen SM, Harris S, Wu-Wong JR, Wessale JL, Padley RJ, Garrett IR, Chirgwin JM, Guise TA: A causal role for endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of osteoblastic bone metastases. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science USA. 2003, 100: 10954-10959. 10.1073/pnas.1830978100.

Man YG, Fu SW, Schwartz A, Pinzone JJ, Simmens SJ, Berg PE: Expression of BP1, a novel homeobox gene, correlates with breast cancer progression and invasion. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2005, 90: 241-247. 10.1007/s10549-004-4492-9.

Kato T, Sato N, Takano A, Miyamoto M, Nishimura H, Tsuchiya E, Kondo S, Nakamura Y, Daigo Y: Activation of placenta-specific transcription factor distal-less homeobox 5 predicts clinical outcome in primary lung cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008, 14: 2363-2370. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1523.

Zhou QP, Lee TN, Qiu X, Spencer V, de Melo J, Du G, Plews M, Fonseca M, Sun JM, Davie JR, Eisenstat DD: Identification of a direct Dlx homeodomain target in the developing mouse forebrain and retina by optimization of chromatin immunoprecipitation. Nucleic Acid Research. 2004, 32: 884-892. 10.1093/nar/gkh233.

Zerucha T, Stühmer T, Hatch G, Park BK, Long Q, Yu G, Gambarotta A, Schultz JR, Rubenstein JL, Ekker M: A highly conserved enhancer in the Dlx5/Dlx6 intergenic region is the site of cross-regulatory interactions between Dlx genes in the embryonic forebrain. Journal of neuroscience. 2000, 20: 709-721.

Ferrari N, Paleari L, Palmisano GL, Tammaro P, Levi G, Albini A, Brigati C: Induction of apoptosis by fenretinide in tumor cell lines correlates with DLX2, DLX3 and DLX4 gene expression. Oncology Report. 2003, 10: 973-977.

Grimshaw M: Endothelin in breast tumor cell invasion. Cancer Letters. 2005, 222: 129-138. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.029.

Dréau D, Karaa A, Culberson C, Wyan H, McKillop IH, Clemens MG: Bosentan inhibits tumor vascularization and bone metastasis in an immunocompetent skin-fold chamber model of breast carcinoma cell metastasis. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 2006, 23: 41-53. 10.1007/s10585-006-9016-z.

Titus B, Frierson HF, Conaway M, Ching K, Guise T, Chirgwin J, Hampton G, Theodorescu D: Endothelin axis is a target of the lung metastasis suppressor gene RhoGDI2. Cancer Research. 2005, 65: 7320-7327. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1403.

Nelson JB, Love W, Chin JL, Saad F, Schulman CC, Sleep DJ, Qian J, Steinberg J, Carducci M, Group. APS: Phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of atrasentan in patients with nonmetastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer. 2008, 113: 2478-2487. 10.1002/cncr.23864.

Yamashita J, Ogawa M, Sakai K: Prognostic significance of three novel biologic factors in a clinical trial of adjuvant therapy for node-negative breast cancer. Surgery. 1995, 117: 601-608. 10.1016/S0039-6060(95)80001-8.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/649/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Giorgio Merlo for Dlx probes and Prof. Luca Mastracci for human tissue samples. We would like also to express our appreciation to Dr. Michele Cilli, Dr. Daniela Cantatore and Mr. Luca Boni for their valuable technical assistance in perform in vivo experiments and Dr. Francesca Delucchi for histology sections. This study was supported by the Ministero della Salute: Progetto Finalizzato 2006, MIUR: FIRB # RBAU01LM97, the European Consortium CRESCENDO "Nuclear Receptors in development and aging" and by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche - Project DrOS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MM and SA carried out the in vivo experiments, PCR and the ISH. LE carried out the immunohistochemistry. YG carried out the cell cultures. VM performed the microarray data analysis. MM, AS, GL and OB conceived the study, participated in its design and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Monica Morini, Simonetta Astigiano contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Morini, M., Astigiano, S., Gitton, Y. et al. Mutually exclusive expression of DLX2 and DLX5/6 is associated with the metastatic potential of the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. BMC Cancer 10, 649 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-649

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-649