Abstract

Background

The aims of this study were to determine the accuracy of concurrent core needle biopsy (CNB) and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) for breast lesions and to estimate the false-negative rate using the two methods combined.

Methods

Over a seven-year period, 2053 patients with sonographically detectable breast lesions underwent concurrent ultrasound-guided CNB and FNAB. The sonographic and histopathological findings were classified into four categories: benign, indeterminate, suspicious, and malignant. The histopathological findings were compared with the definitive excision pathology results. Patients with benign core biopsies underwent a detailed review to determine the false-negative rate. The correlations between the ultrasonography, FNAB, and CNB were determined.

Results

Eight hundred eighty patients were diagnosed with malignant disease, and of these, 23 (2.5%) diagnoses were found to be false-negative after core biopsy. After an intensive review of discordant FNAB results, the final false-negative rate was reduced to 1.1% (p-value = 0.025). The kappa coefficients for correlations between methods were 0.304 (p-value < 0.0001) for ultrasound and FNAB, 0.254 (p-value < 0.0001) for ultrasound and CNB, and 0.726 (p-value < 0.0001) for FNAB and CNB.

Conclusions

Concurrent CNB and FNAB under ultrasound guidance can provide accurate preoperative diagnosis of breast lesions and provide important information for appropriate treatment. Identification of discordant results using careful radiological-histopathological correlation can reduce the false-negative rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Breast cancer has become a serious threat to women's health in Taiwan over recent decades. Breast cancer ranks fourth among the top 10 causes of death from cancer in women, and the death rate has increased from 5 to 12.8 per 100,000 population in the past two decades (data from the Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taiwan; http://www.doh.gov.tw/statistic/data). Because of this increase in the death rate, screening has become more important in health care in Taiwan, and screening programs with mammography and ultrasound (US) are used routinely. However, as in several Asian countries, Taiwanese women have smaller breasts and denser breast tissue than do Western women,[1, 2] and this can cause false-negative findings on mammography. Breast US is an excellent diagnostic method for efficiently detecting breast tumors in dense breast tissue[3–5].

Breast lesions detected in a screening US should be diagnosed histopathologically because any misdiagnosis can delay treatment of the cancer. Minimizing the number of unnecessary surgeries is essential in the diagnosis and treatment of breast tumors. Three main diagnostic procedures are used in the pathological examination of suspicious breast lesions: fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), core needle biopsy (CNB), and surgical open biopsy. FNAB and CNB are minimally invasive procedures that can be performed on an outpatient basis[6, 7].

The diagnostic accuracies of CNB and FNAB have been compared. FNAB is a relevant test, especially in combination with palpation and imaging findings[8–10]. Compared with histological evaluation, CNB is generally considered to produce better results than the cytological results acquired by FNAB,[11–15] especially for lesions highly suspected of being malignant. However, a CNB can produce false-negative results because of missampling or technical failure. Both FNAB and CNB have a specificity approaching 100% in the presence of carcinoma, but their sensitivities range between 80% and 97%. The overall sensitivity may increase when the tests are combined[6, 7, 14, 15, 17].

In this investigation, we analyzed data derived from a combination of FNAB and CNB under US guidance. The objectives of this study were to confirm the diagnostic accuracy of concurrent US-guided FNAB and CNB and to analyze the methodology to identify and reduce the rate of false-negative diagnoses.

Methods

Study population

From April 2000 to June 2007, the study population of women with breast abnormalities who presented with ultrasonically visible lesions was evaluated at National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan, using US-guided FNAB and CNB. A total of 2053 patients (age range, 12-102 years; mean age, 44.8 years) were identified. No initial biopsies by surgical excision, stereotactic biopsy, or any other studies of these lesions were performed before the US-guided biopsies. Patients with lesions not clearly visualized on US were excluded from this study. Ethical approval was provided by Human Experiment and Ethics committee of the National Cheng Kung University Hospital (ER-99-074).

Concurrent US-guided CNB and FNAB were used to evaluate all sonographically visible lesions and were performed in the supine position with the arm elevated, using a high-resolution 10-14-MHz linear array transducer with adjustable puncture and biopsy guides (Falcon Premium 2101, B-K Medical's, Herlev, Denmark). All procedures were performed under local anesthesia via an injection of 5 cc of 1% lidocaine into the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and around the tumor. For FNAB, the specimen was taken with at least 10 passes without needle withdrawal and under constant negative pressure. The cytology was checked immediately under a microscope in the outpatient clinic to ensure that examinable cells were obtained. For CNB, a 14-gauge automated needle device with a 22 mm throw biopsy gun (Bard-Magnum Biopsy Instrument, Covington, GA, USA) was used. The needle was placed at the edge of the lesion in the prefiring position, and the 22 mm core needle throw was executed. The passage of the needle across the index lesion was confirmed under direct visualization with postfire US images. At least five specimens were obtained from each lesion. Specimens were placed in formalin and then submitted for histopathological evaluation; the number of samples was dependent on the lesion size, consistency, and ultrasonographic visibility. Patients with discordance between the core biopsy, fine needle biopsy, and US findings were reviewed, and if necessary, another biopsy or further excision was performed.

The records of all pathologic breast reports were collected and classified under the following categories[18].

B: Benign

I: Benign, but uncertain malignant potential

S: Suspicious of malignancy

M: Malignant

The findings of all breast US examinations were classified after the modification according to American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System Atlas for Ultrasound[19] as follows.

B: Benign (BI-RADS II)

I: Probably benign findings (BI-RADS III)

S: Suspicion of malignancy (BI-RADS IV)

M: Highly suggestive of malignancy (BI-RADS V)

For patients with lesions with a benign finding after the rebiopsy, a sonography follow-up at 6 months was recommended. For evaluation of false-negative cases, the case series were reviewed through linkage with the National Cancer Registry of Taiwan.

Statistical analysis

After tabulation of the data, the specificity, sensitivity, negative and positive predictive values, false-negative rate, false-positive rate, and accuracy were determined for the types of lesion to calculate whether the concurrent CNB and FNAC results agreed with the histopathological findings of the final excisional biopsy, surgery, or clinical follow-up. Chi-squared test assessed paired observation on two variables, which independent of each other. Kappa coefficient measures the agreement between the binary variable. All p-values were two-tailed, with p = 0.05 or lower considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 13.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

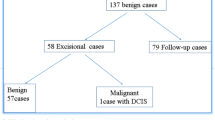

CNB and FNAB under US guidance were performed concurrently to assess the breast lesions by ascertaining a histological diagnosis. A total of 2053 CNB and FNAB were performed. Of these, 880 patients were diagnosed with malignant disease. On US, the average size of the lesion was 16.7 mm (median 13 mm; range 4-150 mm). The sensitivity of CNB and FNAB under US guidance to identify infiltrating breast lesions was 98% and 95%, and the specificity was 99% and 86%, respectively. The correlation between US and FNAB was 306.775 (p < 0.0001) on the chi-squared test, and the kappa coefficient was 0.304 (p < 0.0001). The sensitivity and specificity were 27.07% and 97.91%, respectively. The positive predictive value was 86.12%, and the negative predictive value was 73.7% (Table 1). The correlation between US and CNB was 289.732 (p < 0.0001) on the chi-squared test, and the kappa coefficient was 0.254 (p < 0.0001). The sensitivity and specificity were 23.3% and 99.66%, respectively. The positive predictive value was 98.09%, and the negative predictive value was 63.39% (Table 2). The correlation between FNAB and CNB was 1137.806 (p < 0.0001) on the chi-squared test, and the kappa coefficient was 0.726 (p < 0.0001). The sensitivity and specificity were 72.61% and 97.78%, respectively. The positive predictive value was 96.09%, and the negative predictive value was 82.64% (Table 3).

Clinical features of false-negative CNB findings

Overall, 23 patients had an initial benign CNB and a subsequent diagnosis of malignancy, giving a false-negative rate of 2.5%. The distribution of the pathology of these cases was as follows: intraductal papilloma (n = 6), fibrocystic change (n = 5), atypical ductal hyperplasia (n = 4), fibrous mastopathy (n = 2), papillary lesion (n = 1), sclerosing adenosis (n = 1), lactating adenosis (n = 1), atypical cell (n = 1), chronic inflammation (n = 1), and other (n = 1) (Table 4).

Correlation between the FNAB and CNB findings

In 13 of the 23 false-negative cases, malignancy was shown in the FNAB (adenocarcinoma in patients 1, 4-7, 9, 12-14, 16, 19, 20, and 22) (Table 4). Using this information, the number of false-negative cases could be reduced to 10, which produced a false-negative rate of 1.1%.

Compared with the rate of 2.5% obtained by CNB only, concurrent examination with CNB and FNAB reduced the false-negative rate by 44% (2.5% to 1.1%, p = 0.025).

In these 23 false-negative cases, discordance was recognized immediately in nine because the CNB diagnosis was either papilloma (patients 2, 8, 10, 17, and 18) or atypia (patient 11), and there was a malignant appearance in one patient on sonography (patient 15), which required an open biopsy. In two cases (patients 3 and 21), microcalcification was recognized on mammography one year later, and patient 23 showed progression at the annual follow-up.

Discussion

Accurate preoperative assessment of breast lesions is crucial for treatment planning. In particular, image-guided biopsy has become an established technique. Information on the best biopsy modality to secure a diagnosis of breast lesions is controversial. CNB has been shown to be an excellent tool when working with true tissue specimens because it permits the evaluation of both the architectural and cytological patterns. The diagnostic accuracy of routine paraffin-embedded CNB samples has been verified since the early 1990s, and in their review article, Usami et al reported high concordance between the diagnoses from CNB and surgical biopsy[20]. The study by Dillon et al of 2427 core biopsies taken using three different CNB modalities had an overall false-negative rate of 6.1%. However, US-guided CNB showed the lowest false-negative rate of 1.7%[21]. The accuracy of CNB is associated with the number of CNBs taken. In a prospective study of FNAC and CNB in the diagnosis of breast cancer in 143 patients with a palpable lump measuring > 2 cm,[22] four core biopsy specimens were taken with a 14-gauge 10 cm biopsy needle using an automated spring-loaded device. The sensitivity of CNB increased with the number of cores taken (one core, 76.2%; two cores, 80.9%; three cores, 89.2%; four cores, 95.2%)[6]. To ensure accuracy, at least five cores were taken from each of our patients.

FNAB is a simple, quick, and relatively painless procedure. However, the false-negative rate in the presence of cancer is 6-11%[8, 23]. Factors that may influence these results include the experience of the clinician and pathologist, and the size and histological type of the tumor[7, 24]. Inadequate sampling is a contributory factor to the reduced sensitivity of cytology. This can be improved by instant cytodiagnosis after sampling in the outpatient clinic, which can also confirm the presence of examinable cells. If the examined cells are absent, the sampling will repeat immediately in the outpatient clinic. Nevertheless, the reading of the CNB slides is only possible after formalin fixation by the pathologist.

For the diagnosis of sonographically detectable breast lesions, US-guided FNAB was performed as the initial sampling method, and only for uncertain lesions, a complementary CNB was performed at our facility. This study provides data on US-guided biopsy, particularly in relation to the proportion of breast cancer cases in the study population. US-guided techniques are performed in real time, and the direct visualization of needle placement with US allows the accuracy of the sampling to be assessed. The procedure time is also shorter. Therefore, US-guided biopsies have considerable advantages over stereotactic techniques. US-guided biopsy causes less patient discomfort compared with a stereotactic-guided biopsy because the patient is in a prone position, and it does not involve ionizing radiation and is less expensive than stereotactic techniques[8, 25–27]. False-negative rates of 0.6-22.2% have been reported [11, 22, 26, 28–46]. Only a few studies have been published on sonographic guidance [26, 28, 32, 43, 46]. To our knowledge, our study involves one of the largest sample sizes studied to investigate US-guided biopsy and demonstrates that the combination of FNAB and CNB is accurate with a false-negative rate of 1.1%.

A false-negative diagnosis may delay the treatment of breast cancer. The analysis by Dillon et al of the management and outcome of patients with false-negative cores showed that reviewing the radiological, clinical, and pathological results after the biopsy reduces the delay in the cancer diagnosis to less than one month[21]. US and clinical findings were found to raise the level of suspicion in most of these cases, and FNAB can help the clinician recognize suspicious lesions. In 13 of the 23 patients with false-negative biopsies in our study, it was primarily the FNAB findings that prompted further investigation. This demonstrates a benefit of FNAB because it decreased the false-negative rate by 44% in patients who had this procedure. Combining CNB and FNAB techniques improves the sensitivity of the diagnostic procedure and is supported by other studies[7, 13, 15, 17, 47].

FNAB and CNB are complementary in the accurate diagnosis of breast cancer. There is a small risk of misdiagnosis, which was shown by the need for an open surgical approach in nine patients. Concurrent CNB and FNAB as routine assessments could have reduced the false-negative rate in our study from 2.5% (23 of 903) to 1.1% (10 of 903). Thirteen invasive cancers were found by FNAB after being proved by open biopsy despite a benign diagnosis after CNB. Because the cytological finding did not agree with the suspicious FNAB results, 13 patients were shown to have invasive cancers. After subtracting these cases, only 10 cases of true core misses would have had a false-negative diagnosis and resulted in the subsequent suboptimal treatment of patients. Fortunately, one of these lesions was removed at the patient's request. Therefore, if a discordant benign lesion in a core biopsy is recognized promptly by FNAB, a re-biopsy is warranted, so that a false-negative diagnosis can be identified and prevented. To identify the discordance between imaging, FNAB, and CNB, the breast specialist must be familiar with the sonographic features and the histopathological details, and be able to correlate these data. Our classification using four categories can simplify the diagnosis and thus improve the detection of false-negative cases.

High-risk lesions that have uncertain malignant potential or are suspicious for malignancy, such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, papillary lesions, or fibrocystic changes with atypical features, can cause the underestimation of carcinoma [48–53]. Some authors have suggested using a second biopsy or open biopsy in cases of imaging-histological discordance[54, 55]. There is a lack of clarity regarding the optimal management of these lesions. Our study shows that FNAB might reduce the need for an unnecessary open biopsy of these lesions. However, papillary lesions can cause underestimation of breast carcinoma[56]. In some institutions, surgical excision is performed for papillary lesions[57–60]. In a review of 57 patients with different papillary subtypes, Sydnor showed an incidence of carcinoma in benign papilloma of 3% compared with 67% for atypical papilloma[61]. This demonstrates the wide spectrum of papillary lesions and the indications for surgical excision. Papillary lesions tend to present with intralesional heterogeneity, and there is a risk of concurrent or subsequent malignancy.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that concurrent US-guided CNB and fine needle biopsy are accurate for the histological diagnosis of breast tumors. The combination of histopathological and radiological findings can provide important information for the prompt recognition of the discordant results in the one-stop breast outpatient clinic. Using a combined US, FNAB, and CNB assessment and review could minimize the delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer in women with false-negative core biopsies.

References

Hou MF, Chuang HY, Ou-Yang F, Wang CY, Huang CL, Fan HM, Chuang CH, Wang JY, Hsieh JS, Liu GC, et al: Comparison of breast mammography sonography and physical examination for screening women at high risk of breast cancer in taiwan. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002, 28 (4): 415-420. 10.1016/S0301-5629(02)00483-0.

Huang CS, Chang KJ, Shen CY: Breast cancer screening in Taiwan and China. Breast Dis. 2001, 13: 41-48.

Crystal P, Strano SD, Shcharynski S, Koretz MJ: Using sonography to screen women with mammographically dense breasts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003, 181 (1): 177-182.

Uchida K, Yamashita A, Kawase K, Kamiya K: Screening ultrasonography revealed 15% of mammographically occult breast cancers. Breast Cancer. 2008, 15 (2): 165-168. 10.1007/s12282-007-0024-x.

Ohta T, Okamoto K, Kanemaki Y, Tsujimoto F, Nakajima Y, Fukuda M, Suka M: Use of ultrasonography as an alternative modality for first-line examination in detecting breast cancer in selected patients. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007, 7 (8): 624-626. 10.3816/CBC.2007.n.020.

Dennison G, Anand R, Makar SH, Pain JA: A prospective study of the use of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Breast J. 2003, 9 (6): 491-493. 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09611.x.

Farshid G, Rush G: The use of fine-needle aspiration cytology and core biopsy in the assessment of highly suspicious mammographic microcalcifications: analysis of outcome for 182 lesions detected in the setting of a population-based breast cancer screening program. Cancer. 2003, 99 (6): 357-364. 10.1002/cncr.11785.

Hitchcock A, Hunt CM, Locker A, Koslowski J, Strudwick S, Elston CW, Blamey RW, Ellis IO: A one year audit of fine needle aspiration cytology for the pre-operative diagnosis of breast disease. Cytopathology. 1991, 2 (4): 167-176. 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1991.tb00402.x.

Bulgaresi P, Cariaggi P, Ciatto S, Houssami N: Positive predictive value of breast fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in combination with clinical and imaging findings: a series of 2334 subjects with abnormal cytology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006, 97 (3): 319-321. 10.1007/s10549-005-9126-3.

Pilgrim S, Ravichandran D: Fine needle aspiration cytology as an adjunct to core biopsy in the assessment of symptomatic breast carcinoma. Breast. 2005, 14 (5): 411-414. 10.1016/j.breast.2004.11.001.

Ciatto S, Houssami N, Ambrogetti D, Bianchi S, Bonardi R, Brancato B, Catarzi S, Risso GG: Accuracy and underestimation of malignancy of breast core needle biopsy: the Florence experience of over 4000 consecutive biopsies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 101 (3): 291-297. 10.1007/s10549-006-9289-6.

Jackman RJ, Marzoni FA: Needle-localized breast biopsy: why do we fail?. Radiology. 1997, 204 (3): 677-684.

Crowe JP, Rim A, Patrick RJ, Rybicki LA, Grundfest-Broniatowski SF, Kim JA, Lee KB: Does core needle breast biopsy accurately reflect breast pathology?. Surgery. 2003, 134 (4): 523-526. 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00269-1. discussion 526-528.

Berner A, Davidson B, Sigstad E, Risberg B: Fine-needle aspiration cytology vs. core biopsy in the diagnosis of breast lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003, 29 (6): 344-348. 10.1002/dc.10372.

Hatada T, Ishii H, Ichii S, Okada K, Fujiwara Y, Yamamura T: Diagnostic value of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy core-needle biopsy and evaluation of combined use in the diagnosis of breast lesions. J Am Coll Surg. 2000, 190 (3): 299-303. 10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00300-2.

Agarwal T, Patel B, Rajan P, Cunningham DA, Darzi A, Hadjiminas DJ: Core biopsy versus FNAC for palpable breast cancers. Is image guidance necessary?. Eur J Cancer. 2003, 39 (1): 52-56. 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00459-8.

Westenend PJ, Sever AR, Beekman-De Volder HJ, Liem SJ: A comparison of aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in the evaluation of breast lesions. Cancer. 2001, 93 (2): 146-150. 10.1002/cncr.9021.

Tsuchiya S, Akiyama F, Moriya T, Tsuda H, Umemura S, Katayama Y, Ishihara A, Inai Y, Itoh H, Kitamura T: A new reporting form for breast cytology. Breast Cancer. 2009, 16 (3): 202-206. 10.1007/s12282-009-0128-6.

Mendelson EB BJ, Berg W, Merritt C, Rubin E: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System BIRADS: Ultrasound. 2003, Reston VA: American College of Radiology

Usami S, Moriya T, Kasajima A, Suzuki A, Ishida T, Sasano H, Ohuchi N: Pathological aspects of core needle biopsy for non-palpable breast lesions. Breast Cancer. 2005, 12 (4): 272-278. 10.2325/jbcs.12.272.

Dillon MF, Hill AD, Quinn CM, O'Doherty A, McDermott EW, O'Higgins N: The accuracy of ultrasound stereotactic, and clinical core biopsies in the diagnosis of breast cancer with an analysis of false-negative cases. Ann Surg. 2005, 242 (5): 701-707. 10.1097/01.sla.0000186186.05971.e0.

Gisvold JJ, Goellner JR, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Sykes MW, Karsell PR, Coffey SL, Jung SH: Breast biopsy: a comparative study of stereotaxically guided core and excisional techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994, 162 (4): 815-820.

Park IA, Ham EK: Fine needle aspiration cytology of palpable breast lesions. Histologic subtype in false negative cases. Acta Cytol. 1997, 41 (4): 1131-1138.

Lamb J, Anderson TJ: Influence of cancer histology on the success of fine needle aspiration of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 1989, 42 (7): 733-735. 10.1136/jcp.42.7.733.

Mainiero MB, Gareen IF, Bird CE, Smith W, Cobb C, Schepps B: Preferential use of sonographically guided biopsy to minimize patient discomfort and procedure time in a percutaneous image-guided breast biopsy program. J Ultrasound Med. 2002, 21 (11): 1221-1226.

Sauer G, Deissler H, Strunz K, Helms G, Remmel E, Koretz K, Terinde R, Kreienberg R: Ultrasound-guided large-core needle biopsies of breast lesions: analysis of 962 cases to determine the number of samples for reliable tumour classification. Br J Cancer. 2005, 92 (2): 231-235.

Shah VI, Raju U, Chitale D, Deshpande V, Gregory N, Strand V: False-negative core needle biopsies of the breast: an analysis of clinical radiologic, and pathologic findings in 27 concecutive cases of missed breast cancer. Cancer. 2003, 97 (8): 1824-1831. 10.1002/cncr.11278.

Cassano E, Urban LA, Pizzamiglio M, Abbate F, Maisonneuve P, Renne G, Viale G, Bellomi M: Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted core breast biopsy: experience with 406 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 102 (1): 103-110. 10.1007/s10549-006-9305-x.

Rissanen TJ, Makarainen HP, Kiviniemi HO, Suramo : Ultrasonographically guided wire localization of nonpalpable breast lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 1994, 13 (3): 183-188.

Pijnappel RM, Donk van den M, Holland R, Mali WP, Peterse JL, Hendriks JH, Peeters PH: Diagnostic accuracy for different strategies of image-guided breast intervention in cases of nonpalpable breast lesions. Br J Cancer. 2004, 90 (3): 595-600. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601559.

Andreu FJ, Sentis M, Castaner E, Gallardo X, Jurado I, Diaz-Ruiz MJ, Mendez I, Rey M, Florensa R: The impact of stereotactic large-core needle biopsy in the treatment of patients with nonpalpable breast lesions: a study of diagnostic accuracy in 510 consecutive cases. Eur Radiol. 1998, 8 (8): 1468-1474. 10.1007/s003300050577.

Buchberger W, Niehoff A, Obrist P, Rettl G, Dunser M: Sonographically guided core needle biopsy of the breast: technique accuracy and indications. Radiologe. 2002, 42 (1): 25-32. 10.1007/s117-002-8113-9.

Crystal P, Koretz M, Shcharynsky S, Makarov V, Strano S: Accuracy of sonographically guided 14-gauge core-needle biopsy: results of 715 consecutive breast biopsies with at least two-year follow-up of benign lesions. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005, 33 (2): 47-52. 10.1002/jcu.20089.

Dahlstrom JE, Jain S, Sutton T, Sutton S: Diagnostic accuracy of stereotactic core biopsy in a mammographic breast cancer screening programme. Histopathology. 1996, 28 (5): 421-427. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.332376.x.

Duncan JL, Cederbom GJ, Champaign JL, Smetherman DH, King TA, Farr GH, Waring AN, Bolton JS, Fuhrman GM: Benign diagnosis by image-guided core-needle breast biopsy. Am Surg. 2000, 66 (1): 5-9. discussion 9-10.

Elvecrog EL, Lechner MC, Nelson MT: Nonpalpable breast lesions: correlation of stereotaxic large-core needle biopsy and surgical biopsy results. Radiology. 1993, 188 (2): 453-455.

Fuhrman GM, Cederbom GJ, Bolton JS, King TA, Duncan JL, Champaign JL, Smetherman DH, Farr GH, Kuske RR, McKinnon WM: Image-guided core-needle breast biopsy is an accurate technique to evaluate patients with nonpalpable imaging abnormalities. Ann Surg. 1998, 227 (6): 932-939. 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00017.

Jackman RJ, Nowels KW, Rodriguez-Soto J, Marzoni FA, Finkelstein SI, Shepard MJ: Stereotactic, automated large-core needle biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions: false-negative and histologic underestimation rates after long-term follow-up. Radiology. 1999, 210 (3): 799-805.

Lee CH, Philpotts LE, Horvath LJ, Tocino I: Follow-up of breast lesions diagnosed as benign with stereotactic core-needle biopsy: frequency of mammographic change and false-negative rate. Radiology. 1999, 212 (1): 189-194.

Liberman L, Feng TL, Dershaw DD, Morris EA, Abramson AF: US-guided core breast biopsy: use and cost-effectiveness. Radiology. 1998, 208 (3): 717-723.

Nguyen M, McCombs MM, Ghandehari S, Kim A, Wang H, Barsky SH, Love S, Bassett LW: An update on core needle biopsy for radiologically detected breast lesions. Cancer. 1996, 78 (11): 2340-2345. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961201)78:11<2340::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-0.

Parker SH, Jobe WE, Dennis MA, Stavros AT, Johnson KK, Yakes WF, Truell JE, Price JG, Kortz AB, Clark DG: US-guided automated large-core breast biopsy. Radiology. 1993, 187 (2): 507-511.

Schoonjans JM, Brem RF: Fourteen-gauge ultrasonographically guided large-core needle biopsy of breast masses. J Ultrasound Med. 2001, 20 (9): 967-972.

Smith DN, Rosenfield Darling ML, Meyer JE, Denison CM, Rose DI, Lester S, Richardson A, Kaelin CM, Rhei E, Christian RL: The utility of ultrasonographically guided large-core needle biopsy: results from 500 consecutive breast biopsies. J Ultrasound Med. 2001, 20 (1): 43-49.

Verkooijen HM: Diagnostic accuracy of stereotactic large-core needle biopsy for nonpalpable breast disease: results of a multicenter prospective study with 95% surgical confirmation. Int J Cancer. 2002, 99 (6): 853-859. 10.1002/ijc.10419.

Youk JH, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Oh KK: Sonographically guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy of breast masses: a review of 2,420 cases with long-term follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008, 190 (1): 202-207. 10.2214/AJR.07.2419.

Ibrahim AE, Bateman AC, Theaker JM, Low JL, Addis B, Tidbury P, Rubin C, Briley M, Royle GT: The role and histological classification of needle core biopsy in comparison with fine needle aspiration cytology in the preoperative assessment of impalpable breast lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2001, 54 (2): 121-125. 10.1136/jcp.54.2.121.

Carder PJ, Garvican J, Haigh I, Liston JC: Needle core biopsy can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. Histopathology. 2005, 46 (3): 320-327. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02082.x.

Dillon MF, McDermott EW, Hill AD, O'Doherty A, O'Higgins N, Quinn CM: Predictive value of breast lesions of "uncertain malignant potential" and "suspicious for malignancy" determined by needle core biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007, 14 (2): 704-711. 10.1245/s10434-006-9212-8.

Houssami N, Ciatto S, Bilous M, Vezzosi V, Bianchi S: Borderline breast core needle histology: predictive values for malignancy in lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3). Br J Cancer. 2007, 96 (8): 1253-1257. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603714.

Moore MM, Hargett CW, Hanks JB, Fajardo LL, Harvey JA, Frierson HF, Slingluff CL: Association of breast cancer with the finding of atypical ductal hyperplasia at core breast biopsy. Ann Surg. 1997, 225 (6): 726-731. 10.1097/00000658-199706000-00010. discussion 731-723.

Yeh IT, Dimitrov D, Otto P, Miller AR, Kahlenberg MS, Cruz A: Pathologic review of atypical hyperplasia identified by image-guided breast needle core biopsy. Correlation with excision specimen. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003, 127 (1): 49-54.

Liberman L, Cohen MA, Dershaw DD, Abramson AF, Hann LE, Rosen PP: Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at stereotaxic core biopsy of breast lesions: an indication for surgical biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995, 164 (5): 1111-1113.

Liberman L, Drotman M, Morris EA, LaTrenta LR, Abramson AF, Zakowski MF, Dershaw DD: Imaging-histologic discordance at percutaneous breast biopsy. Cancer. 2000, 89 (12): 2538-2546. 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2538::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-#.

Renshaw AA, Cartagena N, Schenkman RH, Derhagopian RP, Gould EW: Atypical ductal hyperplasia in breast core needle biopsies. Correlation of size of the lesion complete removal of the lesion and the incidence of carcinoma in follow-up biopsies. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001, 116 (1): 92-96. 10.1309/61HM-89TD-0M3L-JAHH.

Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, Wilson A, Herbert G, Perry J, Eckert M, Smith D, Groo S, Brown T: Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007, 14 (10): 2979-2984. 10.1245/s10434-007-9470-0.

Liberman L, Bracero N, Vuolo MA, Dershaw DD, Morris EA, Abramson AF, Rosen PP: Percutaneous large-core biopsy of papillary breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999, 172 (2): 331-337.

Masood S, Loya A, Khalbuss W: Is core needle biopsy superior to fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of papillary breast lesions?. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003, 28 (6): 329-334. 10.1002/dc.10251.

Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM, Singer CI, Cangiarella J: Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2006, 238 (3): 801-808. 10.1148/radiol.2382041839.

Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G, Schniederjan M, Wood WC, Mosunjac M: Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008, 15 (4): 1040-1047. 10.1245/s10434-007-9780-2.

Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA, Massey HD, Shaw de Paredes ES: Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2007, 242 (1): 58-62. 10.1148/radiol.2421031988.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/371/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was presented and awarded at the 17th Asian Congress of Surgery, March 20-22, 2009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CTW designed the concept of this study, drafted the manuscript and performed treatment. CTW collected the data. KYL performed the statistical analysis. KYL designed the concept of this study and provided treatment coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, YL., Chang, TW. Can concurrent core biopsy and fine needle aspiration biopsy improve the false negative rate of sonographically detectable breast lesions?. BMC Cancer 10, 371 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-371

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-371