Abstract

Background

Primary intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is one of the common vascular insults with a relatively high rate of mortality. The aim of the current study was to determine the mortality rate and to evaluate the influence of various factors on the mortality of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Demographic characteristics along with clinical features and neuroimaging information on 122 patients with primary ICH admitted to Sina Hospital between 1999–2002 were assessed by multivariate analysis.

Results

Of 122 patients diagnosed with intracerebral hemorrhage, 70 were men and 52 were women. Sixtynine percent of subjects were between 60 to 80 years of age. A history of hypertension was the primary cause in 67.2% of participants and it was found more frequent compared to other cardiovascular risk factors such as a history of ischemic heart disease (17.2%), diabetes mellitus (18%) and cigarette smoking (13.1%).

The overall mortality rate among ICH patients admitted to the hospital was 46.7%. About one third of the deaths occurred within the first two days after brain injury. Factor independently associated with in-hospital mortality were Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (≤ 8), diabetes mellitus disease, volume of hematoma and and intraventricular hematoma.

Conclusion

Higher rate of mortality were observed during the first two weeks of hospitalization following ICH. Neuroimaging features along with GCS score can help the clinicians in developing their prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in developed countries, after heart disease and cancer, and it is also a leading cause of disability in adults. Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs in 10% to 15% of all stroke cases [1], with an incidence of 10 to 20 per 100,000 [2, 3]. The incidence of ICH increases with age and is more common in men, particularly those above 55 years of age [4].

The high rates of mortality and morbidity with ICH are well recognized. Fortunately, two-thirds of the survivors can live an independent life. The 30-day mortality rate is reported to be around 25% – 50% [2, 5], a majority of them die soon after the stroke [4, 5]. Though hypertension is the most prevalent risk factor in ICH patients [3], other factors such as apolipoprotein allele E2 or E4, frequent use of alcohol and cigarette smoking are other risk factors [2].

Evaluation of prognostic factors in spontaneous ICH occurrence based on hematoma criteria have been performed by some investigators. Other investigators assessed the role of age, sex, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cigarette smoking on ICH. Each factor appears to impact the outcome of study differently.

The goal of the present study was to investigate the mortality rate and to evaluate the effects of demographic data, vascular risk factors, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Score, Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP), and neuroimaging features of hematoma on a cohort of 122 consecutive primary ICH patients in a prospective stroke registry.

Methods

Data were collected between May 1999 and April 2002 on 122 patients with primary ICH, who were admitted consecutively to the Department of Neurology at Sina Hospital.

All patients with symptoms of cerebrovascular disease were received at the hospital within 48 hours of onset or at the time of onset of symptoms. Subjects were initially observed at the emergency room and subsequently admitted to the Department of Neurology after a brain computed tomography (CT) scan. Upon admission, demographic data, clinical and neurological examinations, laboratory tests (complete blood cell count, biochemical profile, serum electrolytes, and urinalysis), chest radiography and 12 lead electrocardiography were obtained. Neurological examinations were performed twice daily. Patients who exhibited further clinical deterioration underwent a second CT scan. For each patient, demographic data (age and sex), vascular risk factors, MAPs and GCSs upon arrival and neuroimaging findings were recorded. Anamnestic findings consisted of the history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking (>20 cigarettes/day), and previous cerebral infarction.

The anatomic sites and total volumes of hematoma were determined on the CT images. The total volumes of paranchymal hemorrhage were estimated using ellipsoid formula (4/3 π a × b × c), where a, b, and c represents the respective radii in 3 dimensional neuroimaging. Variables in relation to the region of hemorrhage included basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, brainstem, lobar and multiple topographic involvements (when more than one of the aforementioned topographies were affected) and primary intraventricular hemorrhage. Secondary intraventricular hematoma extension was also assessed. Outcome variables included cerebral herniation, cardiac events (cardiac arrhythmia, failure or infarction), respiratory events (infection, embolism) and infectious complications.

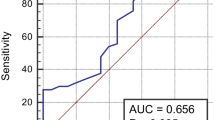

Univariate analysis for each variable (demographic data, vascular risk factors, and neuroimaging features) was assessed using student's t-test and the chi-square test (with Yates correction as needed).

Variables that were significantly related to in-hospital mortality (p < 0.05) or with a p-value of less than 0.3 in univariate analysis plus GCS (used as a continuous variable with a constant odds ratio [OR] for each score) were subjected to multivariate analysis with a logistical regression procedure and forward stepwise selection. Dependent variables coded as zero for surviving and 1 for deceased patients. A first predictive model was based on demographic and vascular risk factors (total of 3 variables). In addition, clinical and neuroimaging variables dichotomized as present or absent were included in the second model (total of 8 variables). Significant level was determined to be 0.15 with the tolerance level at 0.0001. The maximum likelihood approach was used to estimate weights of the logistical parameters. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

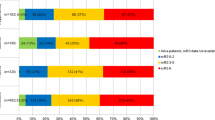

Of the 122 patients (70 men and 52 women) consecutively admitted with ICH, 57 (46.7%) died in the hospital: 31.5% on the first and second days and 82.5% by the fourteenth day of the event. The mean duration between the time of admission and death were 8.21 ± 8.7 days. The mean age of ICH patients were 66 ± 13.28 years (67.3 ± 14.6 for patients who died and 64.9 ± 12.03 for surviving participants, p = 0.34).

Causes of death included cerebral herniation (32 patients), pneumonia (6 patients), sepsis (8 patients), myocardial infarction (2 patients), pulmonary embolism (3 patients), sudden death (2 patients) and unknown causes (4 patients).

A number of ICH patients (9%) were on antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs before the event (one on warfarin, one on heparin, seven on aspirin and two on combination of heparin and low doses aspirin because of myocardial infarction). The two patients on heparin and aspirin died after ICH and brain herniation.

The mean GCS score of surviving patients was 12.8 ± 0.37 compared to a mean GCS score of 8.5 ± 0.50 of those who died (p < 0.001). In another model, patients with a GCS score of >8 compared those with a GCS score of ≤8 who exhibited a significant mortality rate (p < 0.001). The mean MAP was at 153.78 ± 34.5 for those who died compared to 154.23 ± 33.1 for surviving patients (p = 0.641).

Ninety percent of patients with a hematoma volume of more than 60 cc died. Data on demographic features, clinical findings and neuroimaging variables are summarized in Table 1.

The locations of hematoma in order of frequency were basal ganglia/internal capsule, lobar, thalamus, multiple site, cerebellum, brainstem and primary intraventricular. Analysis by site of bleeding did not show significant statistical differences with regard to in-hospital mortality (Table 2).

After multivariate analysis, independent prognostic factors associated with in-hospital mortality were GCS score at time of admission, hematoma volume, intraventricular hematoma and diabetes melitus disease (Table 3).

Discussion

Primary intracerebral hemorrhage is one of the most frequent causes of hospital admission and mortality in the world. Mortality rates of 40% to 50% [4–6] have been reported for primary intracerebral hemorrhage. During the course of present study, which took three years, we investigated 122 cases of ICH enrolled in the hospital. Fifty-seven of the subjects died in hospital, 31.5% of which occurred in the first two days. Two Previous studies also reported a higher mortality rate in the first two to four days following hospital admission [4, 5]. Our study indicated the mortality rate of 46.7% with a higher rate of death in men than in women, which is consistent with previously reported studies [5, 6]. Neither the gender mortality, as previously reported by Qureshi [7], nor the mean age among the deceased and surviving patients can be reported as a significant outcome predictor of our investigation.

Other investigators have reported the age of patients (80 and ≥ 85) as a risk factor [1, 8]. Similarly, our data suggest a higher mortality in patients aged ≥ 85. A majority of our patients (approximately 65%) had a history of hypertension, similar to reports of previous studies, 40–84% [5, 10]. Wide variations reported among investigators can be attributed to how successfully hypertension is controlled in different countries.

More deaths were reported by Schwarz [11] among diabetic patients with ICH. Arboix et al showed diabetes mellitus as an independent factor on mortality rate among ICH patients [12]. Similarly, our data suggest diabetes mellitus as an independent factor on mortality rate. Our study shows no correlation in mortality rate among patients who developed ICH as a complication of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drug consumption.

Contrary to previously reported studies [13, 14] that high MAP at the time of hospital admission (>140 mmHg and >145 mmHg) is an independent risk factor on mortality in ICH patients, we didn't observe such phenomenal with our subjects. In our study, the location of hematoma on the right side or left side had no effect on mortality of patients.

Our findings confirmed previously reported results [1, 8, 15] that the volume of hematoma is an independent factor on mortality of ICH patients. Extension of hematoma to ventricles can be a strong predictor for death as was reported by other investigators [1, 9, 12]. Brain midline shift was significantly more frequent in patients who died, a finding similar to a previous report [15].

Conclusion

Our result indicated a higher mortality rate in the first two weeks following ICH. Diabetes mellitus, GCS score at the time of admission, volume of hematoma and intraventricular hematoma could serve as independent prognostic factors for poor outcome and may help clinicians to assess prognoses more accurately.

References

Hemophil JC, Bonvich DC, Besmerits L: The ICH score- A simple reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001, 32: 891-897.

Woo D, Souerbeck LR, Kissela BM: Genetic and environmental risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002, 33: 1190-1195. 10.1161/01.STR.0000014774.88027.22.

Hanel RA, Xavier AR, Mohammad Y: Outcome following intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2002, 24 (1): 58-62. 10.1179/016164102101200041.

Karnik R, Valentin A, Ammerer HP: Outcome in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage; predictor of survival. Wien Klin Wochenscher. 112 (4): 169-173. 2000 Feb 25

Broderick J, Brott T, Tomsick T: Management of intracerebral hemorrhage in a large metropolitan population. Neurosurgery. 1994, 34: 882-887.

Lisk DR, Pasteur W, Rhoades H: Early presentation of hemispheric intracerebral hemorrhage – prediction of outcome and guidelines for treatment allocation. Neurology. 1994, 44: 133-139.

Qureshi AL, Safdar K, Weil J: Predictors of early detorioration and mortality in Black Americans with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1995, 26: 1764-1767.

Arboix A, Llosera AV, Garcia-Eroles L: Clinical features and functional outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients aged 85 and older. JAGS. 2002, 50 (3): 449-454. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50109.x.

Cheung RTF, Yuzou L: Use of original, modified, or new intracerebral hemorrhage score to predict mortality and morbidity after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003, 34: 1717-1724. 10.1161/01.STR.0000078657.22835.B9.

Tuhrim S, Horowitz DR, Sacher M: Validation and comparison of models predicting survival following intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1995, 23: 950-954. 10.1097/00003246-199505000-00026.

Schwarz S, Hafer K, Aschoff A, Schwab S: Incidence and prognostic significance of fever following intracerebrsl hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000, 54 (2): 354-361.

Arboix A, Massons J, Garcia-Eroles L: Diabetes is an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality from acute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23 (10): 1527-1531.

Terayama Y, Tanahashi N, Fukuuchi Y: Prognostic value of admission blood pressure in patients with ICH. Stroke. 1997, 28: 1185-1188.

Fogelholm R, Nutila M: Prognostic value and determinants of first day MAP in spontaneous supratentorial ICH. Stroke. 1997, 28 (7): 1396-1400.

Arboix A, Comes E, Garcia-Eroles l: Site of bleeding and early outcome in primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002, 105: 282-288. 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.1o170.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/4/9/prepub

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Fatemeh Dehghanzadeh and Dr Hajar Tondgooian for their assistance in conducting the proposal and Dr. Mojtaba Mojtahedzadeh, the head of ICU ward for his cooperation and editorial assistance and we also would like to thank Dr. Parvin Tajic for her analysis revision and Mr. Mohammad Reza Razeghi for designing the tables.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

Mansooreh Togha coordinated this study and Khadige Bakhtavar reported the radiologic studies of the patients. The authors read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Togha, M., Bakhtavar, K. Factors associated with in-hospital mortality following intracerebral hemorrhage: a three-year study in Tehran, Iran. BMC Neurol 4, 9 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-4-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-4-9