Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mass and compromised bone structure, heritable traits that contribute to fracture risk. There have been no genome-wide association and linkage studies for these traits using high-density genotyping platforms.

Methods

We used the Affymetrix 100K SNP GeneChip marker set in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) to examine genetic associations with ten primary quantitative traits: bone mineral density (BMD), calcaneal ultrasound, and geometric indices of the hip. To test associations with multivariable-adjusted residual trait values, we used additive generalized estimating equation (GEE) and family-based association tests (FBAT) models within each sex as well as sexes combined. We evaluated 70,987 autosomal SNPs with genotypic call rates ≥80%, HWE p ≥ 0.001, and MAF ≥10% in up to 1141 phenotyped individuals (495 men and 646 women, mean age 62.5 yrs). Variance component linkage analysis was performed using 11,200 markers.

Results

Heritability estimates for all bone phenotypes were 30–66%. LOD scores ≥3.0 were found on chromosomes 15 (1.5 LOD confidence interval: 51,336,679–58,934,236 bp) and 22 (35,890,398–48,603,847 bp) for femoral shaft section modulus. The ten primary phenotypes had 12 associations with 100K SNPs in GEE models at p < 0.000001 and 2 associations in FBAT models at p < 0.000001. The 25 most significant p-values for GEE and FBAT were all less than 3.5 × 10-6 and 2.5 × 10-5, respectively. Of the 40 top SNPs with the greatest numbers of significantly associated BMD traits (including femoral neck, trochanter, and lumbar spine), one half to two-thirds were in or near genes that have not previously been studied for osteoporosis. Notably, pleiotropic associations between BMD and bone geometric traits were uncommon. Evidence for association (FBAT or GEE p < 0.05) was observed for several SNPs in candidate genes for osteoporosis, such as rs1801133 in MTHFR; rs1884052 and rs3778099 in ESR1; rs4988300 in LRP5; rs2189480 in VDR; rs2075555 in COLIA1; rs10519297 and rs2008691 in CYP19, as well as SNPs in PPARG (rs10510418 and rs2938392) and ANKH (rs2454873 and rs379016). All GEE, FBAT and linkage results are provided as an open-access results resource at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?id=phs000007.

Conclusion

The FHS 100K SNP project offers an unbiased genome-wide strategy to identify new candidate loci and to replicate previously suggested candidate genes for osteoporosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength leading to an increased risk of fracture [1]. In the United States alone, there are over 1.5 million fractures each year, including 280,000 hip fractures and 500,000 vertebral fractures. According to the recent U.S. Surgeon General's Report on Skeletal Health, fractures remain a large and growing public health concern [2]. Presently, the gold standard for assessment of fracture risk is measurement of bone mineral density (BMD, g/cm2) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Whereas low BMD is among the strongest risk factors for fracture [3, 4], a number of clinical studies have demonstrated that other measurements, such as quantitative ultrasound (QUS) and bone geometry, are important for fracture prediction and osteoporosis treatment monitoring [5–7]. Thus, QUS of the calcaneus is associated with hip fracture, largely independent of BMD [8, 9]. A growing body of evidence in recent years indicates that femoral geometry also contributes importantly to hip fracture risk [10, 11].

BMD, QUS, and femoral bone geometry are approximately normally distributed, complex traits. A wealth of studies have documented BMD to be under strong genetic control with 50–70% heritability [12, 13]. Similarly, QUS [8, 14, 15] and hip geometry [16–19] are probably regulated by additive genetic factors. However, despite years of research in the field of osteoporosis genetics, progress to date has been modest in successfully identifying major genes determining BMD, QUS, and bone geometry in the general population. The numbers of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and genes linked and/or associated with osteoporosis-related phenotypes continue to expand and the list has become considerably more detailed and complex. More than 20 genome linkage scans to date have revealed multiple QTLs covering all chromosomes but the Y chromosome [20]. Moreover, the results from one study have inconsistently been replicated in other samples. To overcome these obstacles, a collaborative meta-analysis of 9 genome-wide linkage searches of BMD was recently conducted, including data from 11,842 subjects, members of 3,045 families [13]. The meta-analysis suggested a number of specific QTLs to be pursued further (1p13.3-q23.3 and 1q32-q42.3, 3p25.3-p22.1, 11p12-q13.3, 12q24.31-qter, and 18p11-q12.3). An additional factor that adds to the complexity of finding genes for osteoporosis-related traits is the notion (including our own [21, 22]) that QTLs for bone density and geometry [23] are skeletal site-specific, age-group-, and sex-specific [24, 25].

Numerous biological candidate genes for bone phenotypes have also been proposed, but few have been validated with large-scale evidence [13]. Recent meta-analyses for estrogen receptor alpha [26], collagen type I alpha 1 [27], methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, [28] and vitamin D receptor [29] genes demonstrated that the polymorphisms in these genes each explain a small percentage of the variation in BMD or fracture. With the near completion of the International HapMap Project and the rapid improvements in high throughput genotyping technology, the ultimate understanding of the genetic basis of osteoporosis may come from a genome-wide association approach in which the whole human genome is surveyed for common genetic variation in osteoporosis-related heritable quantitative traits such as BMD [19]. To further advance the field of skeletal genetics, efforts are now turning toward studies that are able to cover the vast majority of the genome with a dense set of SNPs, in order to identify the genes linked and/or associated with osteoporosis-related traits. We thus performed genome-wide linkage and association analyses using a dense genome scan in members of extended pedigrees from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS).

Materials and methods

Study sample

The Framingham Osteoporosis Study is an ancillary study of the Framingham Heart Study (see description of the FHS sample in the Overview paper [30]). Beginning at biennial examination 20 of the Original Cohort, bone mineral density (BMD) was obtained using single and dual photon absorptiometry. The Original Cohort participants underwent bone densitometry by DXA with a Lunar DPX-L (Lunar Corp., Madison, WI, USA) during their examination 22 (1992–1993). In order to maximize the sample size, we used DXA scans from examination 24 (in 1996–1997) for 31 Original Cohort members who did not have DXAs at examination 22. The Offspring Cohort was scanned with the same machine at their examination cycle 6 or 7 (between 1996 and 2001). Right calcaneal bone ultrasonography (QUS) was performed with a portable QUS device, the Sahara® bone sonometer (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA), in members of the Offspring Cohort at their examination cycle 6/7 and the Original Cohort during their exam 24 assessment. There were 1141 phenotyped individuals, 245 from the Original Cohort (86 men and 159 women, mean age 77.5 yrs) and 896 Offspring Cohort participants (409 men and 487 women, mean age 58.5 yrs), belonging to 241 families.

Phenotype definition and residual creation

Original Cohort participants had bone measures performed at either exam 22 or 24. Offspring Cohort participants had these measures obtained during a period that included part of the official Framingham exams 6 and 7. The following traits were studied: Bone mineral density (including femoral neck, FNBMD; trochanter, TRBMD; L2–L4 lumbar spine, LSBMD); quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus (broadband ultrasound attenuation, BUA; speed of sound, SOS), and geometric indices of the hip from DXA (femoral neck-shaft angle, NSA; femoral neck length, NeckLeng; section modulus, Z, and width, W, at the "narrow neck", Neck, and the shaft, S, regions of the hip). In total, 10 traits are reported here. Details of the measurements and phenotype definition [15, 23, 31] as well as coefficients of variation for the different component variables were previously reported for BUA (5.3%), SOS (0.4%) [32], LSBMD (0.9%), FNBMD (1.7%), TRBMD (2.5%) [33], and for the geometric traits, ranged from 3.3% (NeckW) to 9.1% (NeckLeng) [34].

Multivariate regression analysis was performed in each sex (men and women) and Cohort (Original and Offspring) in order to obtain normalized or ranked residual phenotypes, adjusted for covariates. Table 1 lists the covariates used for each trait. The covariate measurements have been described in previous work [22]. We used ranked residuals in order to correct for the deviations from the normal kurtosis and skewness in some of the phenotypes, since variance component analysis (VCA) is sensitive to the high kurtosis [35].

Genotyping methods

We used the Affymetrix 100K SNP GeneChip marker set in the Framingham Heart Study to examine genetic associations with the above phenotypes (see description of the FHS 100K and Marshfield STRs in the Overview paper [30]). We evaluated autosomal SNPs with genotypic call rates ≥80%, HWE p ≥ 0.001, MAF ≥10% in up to 1141 phenotyped individuals (495 men and 646 women). Ultimately, 70,987 SNPs were analyzed.

Statistical analysis methods

We performed genome-wide association (GWA) analyses by two approaches, using both family-based and population-based methods. (See description of the general statistical methods for GWA and linkage analyses in the Overview paper [30]). Both sex-specific and combined-sexes analyses were performed. We used additive generalized estimating equation (GEE) and family-based association tests (FBAT) models to test associations of our phenotypes. Family based association testing has a great power to detect genetic variants of modest effect size [30, 36].

In order to prioritize SNPs potentially associated with multiple phenotypes, we evaluated several phenotypic subgroups: (1) clinically important bone mineral density traits (FNBMD, TRBMD, LSBMD), (2) a combination of BMDs with BUA, (3) hip geometry (NSA, NeckLeng, NeckW and ShaftW), and (4) hip BMDs with hip geometry. We also focused on BMD in sex-specific subgroups. For each SNP we calculated the number of traits significantly associated with this SNP at alpha <0.01 in both GEE and FBAT, assuring that the FBAT and GEE effects were in the same direction. We then selected top SNPs with highest numbers of nominally significantly associated traits. For identical proportions of nominally significant traits, SNPs were additionally ranked by the mean of GEE p-values across traits (as well, GEE p-values were used for SNP ranking in the sex-specific subgroups due to a small sample size for FBAT analysis).

For SNPs that were selected by more than one strategy and that pertained to a specific gene (according to the NCBI Build 35), we perused Entrez Gene and also queried PubMed using the gene name and "osteoporosis", "fracture" or "bone mass" terms, in order to identify biological plausibility or evidence relating these genes specifically to bone disease.

Variance component analyses (VCA) for all phenotypes were performed on normalized or rank-normalized residuals using the computer package Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR, SFBR/NIH, San Antonio, TX) version 2.0, available online http://www.sfbr.org/solar/doc/00.contents.html. Heritability (h2) of each phenotype was estimated as the proportion of the total phenotypic variance attributable to the additive effects of genes. Subsequent linkage analyses were also conducted using SOLAR. This method, described in detail elsewhere [37] (see description of the linkage methods in the Overview paper [30]), entails specification of the genetic covariance between arbitrary relatives as a function of the identity-by-descent (IBD) relationships at a given marker locus and models the covariance matrix for a pedigree as the sum of the additive genetic covariance attributable to the QTL, the additive genetic covariance due to the effects of loci other than the QTL, and the variance due to unmeasured environmental factors. VCA linkage used IBDs values that were calculated from 11,200 markers.

Results

Bone-related quantitative traits and derived phenotypes analyzed in the FHS 100K SNP resource are listed in Table 1. Each trait was analyzed as multivariable-adjusted residuals from cohort- and sex-specific models; in addition, geometric traits were adjusted for age, age2 only. Among these, the following ten multivariable-adjusted residuals are the primary phenotypes presented here: BMD of the femoral neck (FNBMD; n with data = 1141), trochanter (TRBMD; n = 1141) and the second to fourth vertebral bodies of the lumbar spine (LSBMD; n = 1127); a quantitative ultrasound measure of the calcaneus, broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA; n = 1105); femoral geometry measures at the "narrow neck" region of the hip and the femoral shaft including narrow neck section modulus (NeckZr; n = 1107) and width (NeckWr; n = 1106), femoral shaft section modulus (ShaftZr; n = 1037) and width (ShaftW; n = 1037), femoral neck-shaft angle (NSA; n = 1107), and femoral neck length (NeckLeng; n = 1101). Additional bone-related quantitative phenotypes are available in the FHS 100K SNP resource (web posted at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?id=phs000007) including calcaneal speed of sound; several hip geometry measures including neck cross-sectional moment of inertia; neck, shaft and intertrochanteric buckling ratio, and shaft cross sectional moment of inertia from these same examinations.

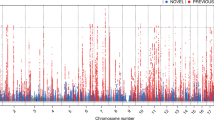

Heritability estimates for all bone phenotypes ranged from 30–66%. We consider here only multivariable-adjusted, residual phenotypes derived from ten primary traits defined above. There were 12 associations with 100K SNPs in GEE models at p < 0.000001 and 2 associations in FBAT models with p < 0.000001. The 25 SNPs with the lowest p-values in GEE (p < 3.5 × 10-6) and FBAT models (p < 2.5 × 10-5), ordered by chromosomal position, are shown in Tables 2a and 2b, respectively. Of these SNPs, 10 (GEE) and 19 (FBAT) were within 60 kb of a known gene. Several SNPs associated with phenotypes were in high pairwise LD (r2 ≥ 0.8). When this occurred we displayed results for the higher ranking SNP based on a combination of FBAT and GEE p-values. Of note, some SNPs were associated with more than one trait: thus, rs10514345 on chromosome 5 was associated (GEE) with NeckZ1 (combined sample) and LSBMD (females) and rs1209921 on chromosome 21 was associated (FBAT) with TRBMD (combined sample) and FNBMD (females) (Tables 2a and 2b, respectively).

In Table 2c we present results with LOD scores above 2.0 from genome-wide linkage analyses with their corresponding 1.5-LOD confidence interval. There were linkage peaks observed for the majority of chromosomes, and in general there were a greater number of linkages with bone geometry traits than with either BMD or ultrasound measures. LOD scores ≥3.0 were found on chromosomes 15 (1.5 LOD support interval, 51,336,679–58,934,236 bp) and 22 (35,890,398–48,603,847 bp), with femoral shaft section modulus. There were no linkage regions of overlap with markers that were found to be associated with bone phenotypes in the FBAT and GEE analyses. Notably, when we restricted our sample to members of the Offspring Cohort, LOD scores for BMD phenotypes increased; for example, for LSBMD on chr. 7 (63,211,216 bp) from 1.25 to 2.43; for FNBMD on chr. 9 (104,660,212 bp) from 1.79 to 2.65, and on chr. 17 (63,038,023 bp) from 1.83 to 2.43 (not shown in the Table 2c).

In order to prioritize SNPs potentially associated with multiple phenotypes, we evaluated four phenotypic subgroups by both population- and family-based tests. The first subgroup was BMD (femoral neck, trochanter and spine), the second was BMD + bone ultrasound (BUA), the third was bone geometry (femoral neck-shaft angle, femoral neck length, femoral neck width, and shaft width), and the fourth, hip BMDs with hip geometry. For each SNP we calculated the number of traits in the subgroup that were significantly associated with the SNP at p < 0.01 in both GEE and FBAT, and then ranked SNPs with highest numbers of nominally significantly associated traits in which the direction of association was the same. In cases where SNPs had the same proportions of nominally significant traits, SNPs were additionally ranked by the mean of GEE p-values across traits.

In Table 3a we present only the SNPs selected based on associations with p-value of both GEE and FBAT < 0.01 with the first subgroup (BMD phenotypes only), for a combined sample of men and women. Using the annotation by UCSC genome browser tables http://genome.ucsc.edu/, of the top 20 SNPs for the BMD subgroup, 9 (45%) were identified in genes or within 60 kb of a known gene, and none were coding (Table 3a). The nominally significant intragenic SNPs were found in several genes, including cadherin 9 type 2 (CDH9) on 5p14 and gene deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) on 18q21. It is also noteworthy that the association of TRBMD with rs1209926 on chr. 21 (39,078,994 bp) occurred in the region identified in our original genome-wide linkage study in the FHS [22] SNP rs2938392 in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) was also associated with the BMD traits in GEE tests and less strongly in FBAT analyses (not shown in Table 3a).

We also examined men and women separately within the first phenotypic subgroup and confirmed the associations of BMD phenotypes, observed in the combined sample, with rs922028 (chromosome 4, no known gene), rs1479679 (in CDH9, chr. 5), and rs768207 (in DCC, chr. 18), all in women (Table 3b). There were also associations in one sex that were neither observed in the other sex nor in the combined sample, and men and women did not share many polymorphisms associated with BMD.

We also looked for evidence of pleiotropy by evaluating association results within the other three pre-specified phenotype subgroups, BMD + BUA and hip geometry, as well as combinations of hip BMD with hip geometry (fourth subgroup). Notably, pleiotropic associations between BMD and other traits were uncommon (not shown in a table). When considering BMD and BUA together (phenotype subgroup 2), there were nominally significant associations (p < 0.0005) with a SNP rs953934 in the interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 gene (IL1RL1) on 2q12 (not shown). Of the top SNPs for the Hip Geometry subgroup (NSA, NeckLeng, NeckW1r and ShaftW1), 50% were identified in genes or within 60 kb of a known gene; none were coding. The nominally significant intragenic SNPs were found in several genes, including rs7151976 in heat shock 70 kD protein 2 (HSPA2) on 14q24 and rs2834719 in runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1, or CBFA2) on 21q22. Significant associations of SNPs with BMD phenotypes did not overlap with geometric phenotypes, and within the hip geometry subgroup, SNPs significant for one geometric phenotype did not overlap with other phenotypes within this subgroup (data not shown).

We further queried the FHS 100K array results, to verify, in silico, whether previously reported candidate genes for osteoporosis were associated with BMD, QUS and bone geometry in our sample. Thus Table 4 shows SNPs in these pre-defined candidate genes that were associated at p ≤ 0.05 in either GEE or FBAT models. We selected the following six previously reported genes that had been extensively studied: COL1A1, CYP19, ESR1, LRP5, MTHFR, and VDR. For the MTHFR gene, we found 1 non-synonymous coding SNP (rs1801133) that was associated with femoral shaft section modulus and neck-shaft angle by GEE and FBAT, respectively. We [38] have previously reported an association of this SNP with BMD in unrelated participants in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study and others have confirmed this association [28, 39]. None of the three 100K SNPs in the ESR1 gene (rs1884052, rs3778099 and rs3866461) with nominally significant associations with bone phenotypes were in LD with widely published SNPs (rs2234693 and rs9340799). A single intronic 100K SNP from LRP5 (rs4988300) was associated with shaft section modulus in males and with femoral neck BMD in females. This 100K SNP was not in LD with published rs3736228 in LRP5 [40]. There were no LD data available on the HapMap website for the SNPs widely studied by others with respect to BMD (rs4988321 and rs627174). For the VDR gene there was a single 100K SNP (rs2189480) nominally significantly associated with femoral neck section modulus and spine BMD; however, there were no data available on LD between this 100K SNP and the 3 out of 5 SNPs reported in a recent meta-analysis of association studies for osteoporosis [29]. Two SNPs reported in that meta-analysis (rs1544410 and rs11568820) were not in LD with the one 100K SNP studied here. There were two 100K SNPs in the CYP19 gene (rs10519297 and rs2008691) associated with femoral neck-shaft angle that were in LD with at least one of the previously reported SNPs studied with respect to bone phenotypes (rs700518, rs4775936, rs10046, and rs11575899). Also, there was a single 100K SNP in the COL1A1 gene (rs2075555) that was associated with femoral neck width in women and shaft width in men; however, there were no data at the HapMap website regarding LD with the three other SNPs in this gene reported by other osteoporosis research groups (rs1107946, rs11327935, rs1800012).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first genome-wide association study of many of the most commonly measured osteoporosis-related phenotypes. This unbiased approach allowed simultaneous exploration of multiple genetic loci rather than focusing on a single-gene association. Using a strategy that combined GEE and FBAT association tests within the subgroup of BMD traits, 40 SNPs were each found to be associated with several bone phenotypes. More than half of these were in or near several genes, including cadherin 9 type 2 (CDH9) on 5p14, nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A gene (NR5A2) at 1q32, gene deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) on 18q21, and PPARG on 3p25. Some of the genes found to be associated with one or several bone density phenotypes have not previously been studied for osteoporosis. Analyses stratified by sex confirmed association of BMD phenotypes with CDH9 and DCC in women. The sex specificity of our findings is fully in line with the previous observations of both sex-specific linkage [13, 21] and sex-specific genetic association with BMD [25, 41].

Our phenotypic subgroup combining BMD and the ultrasound trait, BUA, demonstrated that the interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 (IL1RL1) gene on 2q12 was associated with all bone mass traits. In contrast there was a notable absence of pleiotropic associations between BMD and hip geometry (femoral neck length and width, neck-shaft angle, and shaft width). This is an important observation in light of the current debates about the role of femoral bone geometry in fracture prediction above and beyond BMD, as well as a criticism of DXA-derived bone geometric traits, which are perceived as partially captured in the BMD measurement. We have clearly shown that BMD traits (measured at the femoral neck, trochanter, and at the lumbar spine) share associations with SNPs in several genes, whereas there are no such SNPs that share associations with both hip BMD and hip geometric traits. Despite substantial shared genetic determinants between hip BMD and geometric traits (preliminary unpublished results from our group), these phenotypes are at least in part governed by distinct gene variants. Since genes contributing to variation in BMD do not always contribute to osteoporotic fractures [42], there is a necessity to genetically dissect geometric phenotypes along with BMD to derive a valid endophenotype of osteoporosis and to better encircle the complex heritability of this disease [31].

When we queried the FHS 100K association results, several SNPs in previously well-studied candidate genes for osteoporosis were identified (FBAT or GEE p < 0.05), such as rs1801133 in MTHFR; rs1884052 and rs3778099 in ESR1; rs4988300 in LRP5; rs2189480 in VDR; rs2075555 in COLIA1; rs10519297 and rs2008691 in CYP19. We also examined SNPs in other candidate genes of interest to our group such as SNPs in PPARG (rs10510418 and rs2938392) that were associated with BMD and ultrasound and SNPs in ANKH (rs2454873 and rs379016) that were associated with femoral neck section modulus.

We observed limited overlap between the results of the association and linkage analyses, which may, in part, be attributed to a low power of the linkage analysis. The resolution of linkage peaks depends not only upon the extracted information content of the genotyped markers, but also upon the useful recombination information contained in the sample (which is related to family structure and sample size). Despite low power for detecting modest genetic effects in linkage analyses, we identified several loci with a substantial indication of linkage, such as LOD scores ≥3.0 on chromosomes 15 (around 55,573,538 bp) and 22 (around 44,039,280 bp) for bone geometry phenotypes. Also, LOD scores for BMD phenotypes generally increased after restricting our sample to the members of the Offspring Cohort only, despite potential loss of power due to smaller sample size. This observation indirectly supports our previous finding of refined LOD scores in subgroups of age [21] and may be explained by the younger age of the Offspring Cohort members. The BMD phenotypes in that cohort might be less affected by aging-related artifacts in DXA scans, such as osteophytes, ossification of ligaments, and abdominal aortic calcification. We also observed little overlap between the results of the linkage analysis reported above and our previous studies of the same phenotypes [23, 31], which may, in part, be attributed to low power of these linkage analyses and limited overlap between the 100K sample and the relatively large sample of FHS pedigrees published before [23, 31].

To our knowledge, this is a first genome-wide association study of many of the most commonly measured osteoporosis-related phenotypes. It is distinct in many respects. First, this is a population-based sample rather than a study of affected families. Second, our study included adults from two generations of the same families. The longitudinal nature of the FHS and ongoing recruitment of the third generation (grandchildren of the Original Cohort) will enable us to validate the results of this study with an even larger sample of 3 generations. Third, results of this collaborative effort (FHS 100K SNP study) are publicly available on the web http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?id=phs000007, which makes it a unique resource contributing to ongoing efforts of other groups.

One of the strengths of this study lies in the unbiased approach that allowed simultaneous exploration of multiple genetic loci rather than focusing on a single-gene association. However osteoporosis is likely to be a polygenic condition with a strong environmental component. Therefore, an obvious limitation of this study is the absence of analyses testing gene-environment and gene-by-gene interactions [43], which is a demanding element of study design and statistical analyses. We did not formally test for associations of the SNPs with some known environmental factors, such as smoking or estrogen replacement therapy in women, for which FHS has well-documented longitudinal data, because of sample size considerations.

A second potential limitation of this study is that there may be unmeasured factors that would affect the association or impact on generalizability of our results. Sampling of homogenous individuals is needed to minimize these effects. We attempted to approach this problem in part by stratifying our sample by gender; however, a more involved stratification, such as younger men or postmenopausal women, was not performed due to sample size restrictions. A third potential shortcoming of this study is the limited coverage of the genome by the 100K SNP array. These SNPs are undersampled from coding regions (both non-synonymous and synonymous) and oversampled from regions outside genes, relative to SNPs in the overall HapMap database [44]. Current plans of the FHS include the genotyping and analysis of over half a million genetic variants in approximately 9,000 men and women from three generations of the FHS. This higher density genotyping will provide wider coverage of genomic variation and thus will clearly have advantages for GWA and linkage studies in the future.

Fourth, at the present there is no clear-cut strategy for prioritization of the regions identified by our approach to whole genome analyses. We implemented one possible SNP prioritization strategy based on a somewhat arbitrary grouping of multiple phenotypes. Pleiotropy across different (but probably related) phenotypes may be an indication of genes that influence more than one biological pathway and thus may affect overall risk of osteoporosis.

Finally, we are hesitant to regard any result reported in this paper as genome-wide significant. Although observing evidence for association at a significance level of .0001 in both the GEE and FBAT test is very encouraging, it does not meet the standard of genome-wide significance. Not only do we have a large number of statistical tests for each phenotype, but we also have numerous phenotypes [30]. None of our findings should be considered true positive results until they are replicated in independent samples and/or functional studies are performed that provide the mechanism of the SNP effect.

Conclusions and future directions

An unbiased genome-wide strategy to detect genetic associations with skeletal traits provides an opportunity to identify novel pathways for replication in other human populations. This study is thus hypothesis-generating and awaits replication in comparable samples. On one hand, ample data on genetic markers and associated traits may form the basis of new phenotype definitions, aimed at defining phenotypic groupings that are characterized by the sharing of genetic linkage and association. Such data may uncover biological mechanisms not obvious at the phenotypic level [42]. On the other hand, a composite genetic risk score that combines the effects of multiple loci may prove to be of more practical utility for a common and complex chronic disease such as osteoporosis, [43] rather than results of single-gene association studies. Identification of such a molecular profile and creation of an array for genetic screening will be a very useful tool for prevention and management of osteoporosis.

Abbreviations

- BMD:

-

bone mineral density

- Chr:

-

chromosome

- DXA:

-

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- FBAT:

-

family based association testing

- GEE:

-

generalized estimating equations

- GWA:

-

Genome wide association

- HWE:

-

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- IBD:

-

identity-by-descent

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- LOD:

-

logarithm of the odds

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- QUS:

-

bone quantitative ultrasound

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- VCA:

-

variance component analysis.

References

Klibanski A, Adams-Campbell L, Bassford T, Blair S, Boden S, Dickersin K, Gifford D, Glasse L, Goldring S, Hruska K, Johnson S, McCauley L, Russell W: Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001, 285 (6): 785-795. 10.1001/jama.285.6.785.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services: Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2004, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD

Cummings SR, Melton LJ: Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002, 359 (9319): 1761-1767. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9.

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H: Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures [see comments]. Bmj. 1996, 312 (7041): 1254-1259.

Greenspan SL, Beck TJ, Resnick NM, Bhattacharya R, Parker RA: Effect of hormone replacement, alendronate, or combination therapy on hip structural geometry: a 3-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20 (9): 1525-1532. 10.1359/JBMR.050508.

Uusi-Rasi K, Beck TJ, Semanick LM, Daphtary MM, Crans GG, Desaiah D, Harper KD: Structural effects of raloxifene on the proximal femur: results from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation trial. Osteoporos Int. 2006, 17 (4): 575-586. 10.1007/s00198-005-0028-3.

Uusi-Rasi K, Semanick LM, Zanchetta JR, Bogado CE, Eriksen EF, Sato M, Beck TJ: Effects of teriparatide [rhPTH (1–34)] treatment on structural geometry of the proximal femur in elderly osteoporotic women. Bone. 2005, 36 (6): 948-958. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.003.

Arden NK, Baker J, Hogg C, Baan K, Spector TD: The heritability of bone mineral density, ultrasound of the calcaneus and hip axis length: a study of postmenopausal twins. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1996, 11 (4): 530-534.

Gluer CC, Hans D: How to use ultrasound for risk assessment: a need for defining strategies. Osteoporos Int. 1999, 9 (3): 193-195. 10.1007/s001980050135.

Faulkner KG, Wacker WK, Barden HS, Simonelli C, Burke PK, Ragi S, Del Rio L: Femur strength index predicts hip fracture independent of bone density and hip axis length. Osteoporos Int. 2006, 17 (4): 593-599. 10.1007/s00198-005-0019-4.

Faulkner KG, Cummings SR, Black D, Palermo L, Gluer CC, Genant HK: Simple measurement of femoral geometry predicts hip fracture: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1993, 8 (10): 1211-1217.

Shen H, Recker RR, Deng HW: Molecular and genetic mechanisms of osteoporosis: implication for treatment. Curr Mol Med. 2003, 3 (8): 737-757. 10.2174/1566524033479375.

Ioannidis JP, Ng MY, Sham PC, Zintzaras E, Lewis CM, Deng HW, Econs MJ, Karasik D, Devoto M, Kammerer CM, Spector T, Andrew T, Cupples LA, Duncan EL, Foroud T, Kiel DP, Koller D, Langdahl B, Mitchell BD, Peacock M, Recker R, Shen H, Sol-Church K, Spotila LD, Uitterlinden AG, Wilson SG, Kung AW, Ralston SH: Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans provides evidence for sex- and site-specific regulation of bone mass. J Bone Miner Res. 2007, 22 (2): 173-183. 10.1359/jbmr.060806.

Howard GM, Nguyen TV, Harris M, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA: Genetic and environmental contributions to the association between quantitative ultrasound and bone mineral density measurements: a twin study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998, 13 (8): 1318-1327. 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.8.1318.

Karasik D, Myers RH, Hannan MT, Gagnon D, McLean RR, Cupples LA, Kiel DP: Mapping of quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus bone to chromosome 1 by genome-wide linkage analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2002, 13 (10): 796-802. 10.1007/s001980200110.

Koller DL, Liu G, Econs MJ, Hui SL, Morin PA, Joslyn G, Rodriguez LA, Conneally PM, Christian JC, Johnston CC, Foroud T, Peacock M: Genome screen for quantitative trait loci underlying normal variation in femoral structure. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2001, 16 (6): 985-991. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.985.

Peacock M, Koller DL, Lai D, Hui S, Foroud T, Econs MJ: Sex-specific quantitative trait loci contribute to normal variation in bone structure at the proximal femur in men. Bone. 2005, 37 (4): 467-473. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.005.

Shen H, Long JR, Xiong DH, Liu YJ, Liu YZ, Xiao P, Zhao LJ, Dvornyk V, Zhang YY, Rocha-Sanchez S, Liu PY, Li JL, Deng HW: Mapping quantitative trait loci for cross-sectional geometry at the femoral neck. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20 (11): 1973-1982. 10.1359/JBMR.050715.

Xiong DH, Shen H, Xiao P, Guo YF, Long JR, Zhao LJ, Liu YZ, Deng HY, Li JL, Recker RR, Deng HW: Genome-wide scan identified QTLs underlying femoral neck cross-sectional geometry that are novel studied risk factors of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2006, 21 (3): 424-437. 10.1359/JBMR.051202.

Shen H, Liu Y, Liu P, Recker RR, Deng HW: Nonreplication in genetic studies of complex diseases--lessons learned from studies of osteoporosis and tentative remedies. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20 (3): 365-376. 10.1359/JBMR.041129.

Karasik D, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Kiel DP: Age, gender, and body mass effects on quantitative trait loci for bone mineral density: the Framingham study. Bone. 2003, 33 (3): 308-316. 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00173-X.

Karasik D, Myers RH, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Gagnon DR, Herbert A, Kiel DP: Genome screen for quantitative trait loci contributing to normal variation in bone mineral density: the Framingham Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2002, 17 (9): 1718-1727. 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1718.

Demissie S, Dupuis J, Cupples LA, Beck TJ, Kiel DP, Karasik D: Proximal hip geometry is linked to several chromosomal regions: Genome-wide linkage results from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Bone. 2007, 40 (3): 743-750. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.020.

Ferrari SL, Karasik D, Liu J, Karamohamed S, Herbert AG, Cupples LA, Kiel DP: Interactions of interleukin-6 promoter polymorphisms with dietary and lifestyle factors and their association with bone mass in men and women from the framingham osteoporosis study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004, 19 (4): 552-559. 10.1359/JBMR.040103.

Shearman AM, Karasik D, Gruenthal KM, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Housman DE, Kiel DP: Estrogen receptor Beta polymorphisms are associated with bone mass in women and men: the Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004, 19 (5): 773-781. 10.1359/JBMR.0301258.

Ioannidis JP, Stavrou I, Trikalinos TA, Zois C, Brandi ML, Gennari L, Albagha O, Ralston SH, Tsatsoulis A: Association of polymorphisms of the estrogen receptor alpha gene with bone mineral density and fracture risk in women: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2002, 17 (11): 2048-2060. 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.11.2048.

Mann V, Ralston SH: Meta-analysis of COL1A1 Sp1 polymorphism in relation to bone mineral density and osteoporotic fracture. Bone. 2003, 32 (6): 711-717. 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00087-5.

Riancho JA, Valero C, Zarrabeitia MT: MTHFR polymorphism and bone mineral density: meta-analysis of published studies. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006, 79 (5): 289-293. 10.1007/s00223-006-0143-y.

Uitterlinden AG, Ralston SH, Brandi ML, Carey AH, Grinberg D, Langdahl BL, Lips P, Lorenc R, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Reeve J, Reid DM, Amedei A, Bassiti A, Bustamante M, Husted LB, Diez-Perez A, Dobnig H, Dunning AM, Enjuanes A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Fang Y, Karczmarewicz E, Kruk M, van Leeuwen JP, Mavilia C, van Meurs JB, Mangion J, McGuigan FE, Pols HA, Renner W, Rivadeneira F, van Schoor NM, Scollen S, Sherlock RE, Ioannidis JP: The association between common vitamin D receptor gene variations and osteoporosis: a participant-level meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2006, 145 (4): 255-264.

Cupples L, Arruda H, Benjamin E, D'Agostino R, Demissie S, DeStefano A, Dupuis J, Falls K, Fox C, Gottlieb D, Govindaraju D, Heard-Costa N, Hwang S, Kathiresan S, Kiel D, Laramie J, Larson M, Levy D, Lunetta K, Mailman M, Manning A, Meigs J, Murabito J, Newton-Cheh C, O'Connor G, O'Donnell C, Pandey M, Seshadri S, Vasan R, Wilk J, Wolf P, Yang Q, Atwood L: The Framingham Heart Study 100K SNP genome-wide association study resource: Overview of 17 phenotype working group reports. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8 (Suppl 1): S1-

Karasik D, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Kiel DP: Genome screen for a combined bone phenotype using principal component analysis: the Framingham study. Bone. 2004, 34 (3): 547-556. 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.017.

McLean RR, Hannan MT, Epstein BE, Bouxsein ML, Cupples LA, Murabito J, Kiel DP: Elderly cohort study subjects unable to return for follow-up have lower bone mass than those who can return. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 151 (7): 689-692.

Hannan MT, Felson DT, Dawson-Hughes B, Tucker KL, Cupples LA, Wilson PW, Kiel DP: Risk factors for longitudinal bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000, 15 (4): 710-720. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.710.

Khoo BC, Beck TJ, Qiao QH, Parakh P, Semanick L, Prince RL, Singer KP, Price RI: In vivo short-term precision of hip structure analysis variables in comparison with bone mineral density using paired dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans from multi-center clinical trials. Bone. 2005, 37 (1): 112-121. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.007.

Blangero J, Williams JT, Almasy L: Robust LOD scores for variance component-based linkage analysis. Genet Epidemiol. 2000, 19 (Suppl 1): S8-14. 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Lange C, Silverman EK, Xu X, Weiss ST, Laird NM: A multivariate family-based association test using generalized estimating equations: FBAT-GEE. Biostatistics. 2003, 4 (2): 195-206. 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.195.

Almasy L, Blangero J: Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998, 62 (5): 1198-1211. 10.1086/301844.

McLean RR, Karasik D, Selhub J, Tucker KL, Ordovas JM, Russo GT, Cupples LA, Jacques PF, Kiel DP: Association of a common polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene with bone phenotypes depends on plasma folate status. J Bone Miner Res. 2004, 19 (3): 410-418. 10.1359/JBMR.0301261.

Abrahamsen B, Madsen JS, Tofteng CL, Stilgren L, Bladbjerg EM, Kristensen SR, Brixen K, Mosekilde L: Are effects of MTHFR (C677T) genotype on BMD confined to women with low folate and riboflavin intake? Analysis of food records from the Danish osteoporosis prevention study. Bone. 2005, 36 (3): 577-583. 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.014.

Koller DL, Ichikawa S, Johnson ML, Lai D, Xuei X, Edenberg HJ, Conneally PM, Hui SL, Johnston CC, Peacock M, Foroud T, Econs MJ: Contribution of the LRP5 Gene to Normal Variation in Peak BMD in Women. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20 (1): 75-80. 10.1359/jbmr.2005.20.1.75.

Kiel DP, Ferrari SL, Cupples LA, Karasik D, Manen D, Imamovic A, Herbert AG, Dupuis J: Genetic variation at the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) locus modulates Wnt signaling and the relationship of physical activity with bone mineral density in men. Bone. 2007, 40 (3): 587-596. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.029.

Schulze TG, McMahon FJ: Defining the phenotype in human genetic studies: forward genetics and reverse phenotyping. Hum Hered. 2004, 58 (3–4): 131-138. 10.1159/000083539.

Clark AG, Boerwinkle E, Hixson J, Sing CF: Determinants of the success of whole-genome association testing. Genome Res. 2005, 15 (11): 1463-1467. 10.1101/gr.4244005.

Nicolae DL, Wen X, Voight BF, Cox NJ: Coverage and characteristics of the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 100K SNP set. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2 (5): e67-10.1371/journal.pgen.0020067.

Ioannidis JP, Ralston SH, Bennett ST, Brandi ML, Grinberg D, Karassa FB, Langdahl B, van Meurs JB, Mosekilde L, Scollen S, Albagha OM, Bustamante M, Carey AH, Dunning AM, Enjuanes A, van Leeuwen JP, Mavilia C, Masi L, McGuigan FE, Nogues X, Pols HA, Reid DM, Schuit SC, Sherlock RE, Uitterlinden AG: Differential genetic effects of ESR1 gene polymorphisms on osteoporosis outcomes. Jama. 2004, 292 (17): 2105-2114. 10.1001/jama.292.17.2105.

Ferrari SL, Deutsch S, Choudhury U, Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, Dermitzakis ET, Rizzoli R, Antonarakis SE: Polymorphisms in the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene are associated with variation in vertebral bone mass, vertebral bone size, and stature in whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74 (5): 866-875. 10.1086/420771.

Lorentzon M, Swanson C, Eriksson AL, Mellstrom D, Ohlsson C: Polymorphisms in the aromatase gene predict areal BMD as a result of affected cortical bone size: the GOOD study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006, 21 (2): 332-339. 10.1359/JBMR.051026.

Yang TL, Zhao LJ, Liu YJ, Liu JF, Recker RR, Deng HW: Genetic and environmental correlations of bone mineral density at different skeletal sites in females and males. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006, 78 (4): 212-217. 10.1007/s00223-005-0267-5.

Enjuanes A, Garcia-Giralt N, Supervia A, Nogues X, Ruiz-Gaspa S, Bustamante M, Mellibovsky L, Grinberg D, Balcells S, Diez-Perez A: A new SNP in a negative regulatory region of the CYP19A1 gene is associated with lumbar spine BMD in postmenopausal women. Bone. 2006, 38 (5): 738-743. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.010.

Garcia-Giralt N, Nogues X, Enjuanes A, Puig J, Mellibovsky L, Bay-Jensen A, Carreras R, Balcells S, Diez-Perez A, Grinberg D: Two new single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the COL1A1 upstream regulatory region and their relationship to bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 2002, 17 (3): 384-393. 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.384.

Garcia-Giralt N, Enjuanes A, Bustamante M, Mellibovsky L, Nogues X, Carreras R, Diez-Perez A, Grinberg D, Balcells S: In vitro functional assay of alleles and haplotypes of two COL1A1-promoter SNPs. Bone. 2005, 36: 902-908. 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.012.

Grant SF, Reid DM, Blake G, Herd R, Fogelman I, Ralston SH: Reduced bone density and osteoporosis associated with a polymorphic Sp1 binding site in the collagen type I alpha 1 gene. Nat Genet. 1996, 14 (2): 203-205. 10.1038/ng1096-203.

Acknowledgements

From the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health and Boston University School of Medicine. The Framingham Heart Study core examinations were supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's (Contract No. N01-HC-25195). Measurements of phenotypes were funded by the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute on Aging (grants No. R01 AR/AG 41398 and R01 AR050066).

FHS 100K analyses were conducted using the Boston University. Linux Cluster for Genetic Analysis (LinGA) funded by the NIH NCRR (National Center for Research Resources) Shared Instrumentation grant 1S10RR163736-01A1 http://www.bu.edu/dbin/sph/departments/biostatistics/linga_publications.php.

We gratefully acknowledge the Framingham Study members who participated in this study, as well as the study coordinators, who contributed to the success of this work, as well as Yekyung (Kelly) Cho for her technical assistance, and Dr. L. Adrienne Cupples for her contributions to the design of the study and the statistical analysis.

This article has been published as part of BMC Medical Genetics Volume 8 Supplement 1, 2007: The Framingham Heart Study 100,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms resource. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/8?issue=S1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design or acquisition of phenotypic data. JD participated in the design of the study and performed statistical analyses; DPK, DEK, SD, JMM, and KLL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. DK and DPK drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiel, D.P., Demissie, S., Dupuis, J. et al. Genome-wide association with bone mass and geometry in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet 8 (Suppl 1), S14 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S14

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S14