Abstract

Background

Evidence for the impact of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy on bacteremia is mainly from studies in medical centers. We investigated the impact of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy on bacteremia in a community hospital. In particular, patients from the hospital’s affiliated nursing home were sent to the hospital with adequate referral information.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study to collect data of patients with bacteremia in a community hospital in Taiwan from 2005 to 2007.

Results

A total of 222 patients with blood stream infection were diagnosed, of whom 104 patients (46.8%) died. The rate of initial inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions was high (59%). Multivariate analysis revealed that patients with initial inappropriate antibiotics, patients with ventilator support and patients requiring ICU care were the independent predictors for inhospital mortality. Patients referred from the hospital-affiliated nursing home and patients with normal WBC counts had better survival outcome. More than 80% cases infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Enterococcus faecalis received initial inappropriate antimicrobial therapy. With the longer delay to administer appropriate antibiotic, a trend of higher mortality rates was observed.

Conclusions

Bacteremia patients from a hospital-affiliated nursing home had a better prognosis, which may have been due to the adequate referral information. Clinicians should be aware of the commonly ignored drug resistant pathogens, and efforts should be made to avoid delaying the administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Blood stream infections (BSI) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and they are also associated with an increased one-year mortality rate [1]. Two important factors for the decreased efficacy of antimicrobial therapy are treatment with inappropriate antimicrobial agents and the delay of appropriate antimicrobial therapy [2]. However, the increasing antimicrobial resistance of micro-organisms has decreased the likelihood of patients receiving appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy.

Many studies have reported that inappropriate empirical antimicrobial treatment for BSI resulted in higher patient morbidity and mortality rates and increased healthcare costs [1, 3–11]. Most of these studies were conducted in medical centers and university hospitals. However, other studies have failed to find a relationship between mortality and initial inappropriate antibiotic treatment in BSI patients [12, 13]. The conflicting findings may be due to different rates of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy, the case number in each study, differences in disease severity and comorbidities of the patients, and differences in hospital care systems [14]. It is therefore interesting to investigate the influencing factors in different hospital settings and healthcare systems.

Studies of the impact of inadequacy of antibiotics on BSI patients in medical centers in Taiwan have been reported [3, 6, 15]. However, no studies have focused on community hospital setting. In addition, the correlation of BSI outcomes and different BSI case sources (communities, nursing homes, and hospitals) has never been documented. A current trend in Taiwan is for a hospital to have an affiliated or contracted nursing home that may or may not include respiratory care wards. It is possible for BSI patients who are referred from an affiliated nursing home to the parent hospital to have an advantage over patients admitted directly to the hospital for BSI because healthcare workers of the affiliated nursing home provide patients’ medical information. However, this has not been thoroughly studied before.

We performed this retrospective study in a community hospital in Taiwan. The hospital received cases from the community, including those from the hospital affiliated nursing home with which there was good communication and 24-hour physician coverage. All of the patients residing at the nursing home were sent to the parent hospital when they became ill.

The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of initial inappropriate or appropriate antibiotic treatment, focusing on mortality, pathogens and clinical parameters. We also investigated the epidemiology, microbiology and prognosis in community acquired, nursing home acquired and hospital acquired blood stream infections.

Methods

Study location and patient selection

This study was conducted at Wen-Hsiung Hospital, which is a community hospital located in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. There is a 20-bed respiratory care ward, a 6-bed intensive care unit and a 26-bed ordinary ward in the hospital. Patients in a 128-bed nursing home which is affiliated to Wen-Hsiung Hospital are sent to the hospital when medical needs arise. Patients in the affiliated nursing home are cared for by at least one staff physician from the community hospital either in-house or on-call at all times. For there was no Institute Ethics Committee at the community hospital, this work was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH-IRB-2013003) according to Taiwan national regulation.

All cases of bacteremia were divided into three sources: community acquired, hospital acquired and nursing home acquired. The patients were identified by review of microbiology laboratory records from January 1, 2005 through December 31, 2007. They were included in the study if their blood cultures were drawn either at the hospital or in the emergency department immediately prior to admission, and if the culture results were positive for a fungus or bacteria. Patients younger than 18 years and patients who visited the emergency department but were not hospitalized were excluded. All case records were reviewed by two physicians (Dr. Yang CJ and Dr. Chung YC). All of the clinical and mortality data were obtained from the patients’ medical records as well as their charts.

Definition and data collection

Bloodstream infections was diagnosed by the presence of clinical or laboratory evidence of sepsis. The definition of sepsis was based on the ACCP/SCCM consensus conference committee [16]. The possibility of a contaminated blood culture was determined after agreement by two doctors. A community-acquired BSI was defined when bacteremia occurred within the first 48 hours of hospital admission for patients from the local community. A nursing home-acquired BSI was defined when it occurred at the time of hospital admission or within 48 hours of admission for patients who came from the hospital affiliated nursing home. A hospital-acquired BSI was defined when it occurred more than 48 hours after the beginning of a period of hospitalization. Patients who were transferred from other hospitals or other nursing homes were excluded from the study. In addition, polymicrobial blood stream infections were also excluded.

Mortality was the main outcome. Appropriate antibiotic therapy was defined as the initial antimicrobial agent being active in vitro against the infecting organism, and if the drug was given at an appropriate dose and by appropriate route of administration. Initial therapy was defined as the antibiotics received on the first day of therapy for the BSI. Time to appropriate antibiotic administration was recorded in the inappropriate therapy group.

Information with regards to comorbid medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver cirrhosis, ventilator support, end stage renal disease, vascular disease (including coronary artery disease and cerebral vascular disease) were documented. The other recorded variables were age, sex, source of infection, leukocytes, use of catheters, tracheostomy status, steroid use, postoperative status, length of stay more than 30 days, hospitalized site, sepsis status (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome), microorganism isolates, CURB-65 score items including confusion, blood urine nitrogen > 20 mg/dl, shock status (systolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg or diastolic pressure < 60 mmHg), respiratory rate > 30 per minute) [17] and the different sources include community, hospital and the hospital affiliated nursing home. The referral medical information from nursing homes included hospitalization history, previous culture report, and recent infection sites, Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the BSI isolates was performed according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory standards [18].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were implemented to summarize the patient characteristics as mean (SD) or proportions. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for the categorical data and the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for the continuous data were used to compare data between different groups. In the multivariaate analysis, we analyzed variables with a P value <0.05 from the univariate analysis. To control for potential confounding factors, a multinominal logistic regression analysis was performed evaluating the possible covariates. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SPSS version 14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

Between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2007, a total of 222 cases of BSI were diagnosed at the hospital. Thirty-six patients had community-acquired, 129 patients had hospital-acquired, and 57 patients had nursing home-acquired BSI. The initial inappropriate antibiotic prescription rate was 59% (131/222). One hundred and four patients (46.8%) died during their hospitalization. Among the three sources, hospital-acquired acquired bacteremia had the worst prognosis with a mortality rate of 58.91%, and patients with nursing home-acquired BSI had the best prognosis, with a mortality rate of 26.3%. In the nursing home-acquired group, the four most common pathogens were Escherichia coli (16 cases, 28.07%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5 cases, 8.77%), Proteus mirabilis (5 cases, 8.77%) and Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (5 cases, 8.77%). The most common sources of infection were urinary tract infections (23 cases, 40.35%) and respiratory tract infections (20 cases, 35.08%).

Univariate analysis of the demographics, comorbidities, laboratory data, sources of infection, sepsis status, admission site and adequacy of the antibiotic treatment with regards to survival and mortality is present in Table 1 and Table 2. Hospital mortality was correlated with older age, higher serum creatinine, lower serum albumin, more ventilator support and more central venous catheterization. The mortality rate was higher in those with a serum white blood cell count > 20 × 103/ul, length of hospital stay > 30 days, hospitalized in the intensive care unit, with septic shock, confused status, blood urine nitrogen > 20 mg/dL, systolic BP < 90 mmHg or diastolic BP < 60 mmHg, nosocomial infection and inappropriate antibiotic treatment. In contrast, those with a normal white blood cell count (between 4 × 103 to 10 × 103/ul), admitted to the ordinary ward, sepsis status and with nursing home-acquired BSI were more likely to survive.

After excluding CURB-65 parameters (confusion, BUN >20, RR > 30, SBP <90, DBP <60) and septic status (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, MODS), the multivariate analysis revealed that the patients from nursing home (OR 0.267, 95% CI 0.091-0.970, P = 0.044), and normal WBC (OR 0.198, CI 0.068-0.574, P = 0.003) were significant for better outcome. In contrast, the patients with Initial inappropriate antibiotics use (OR 3.715, 95% CI 1.736-7.948, P = 0.001). In other hand, patients admitted to ICU (OR 4.241, 95% CI 1.620-11.104, P = 0.003) and needed ventilator use (OR 3.290, CI 1.034-10.466, P = 0.044) had the worst prognosis (Table 3). Furthermore, initial inappropriate antibiotic administration was significant associated with a higher mortality rate (Log Rank Test, P = 0.018) (Figure 1) and delayed appropriate antibiotic administration was associated with a trend of a higher mortality rate (P = 0.07) (Figure 2).

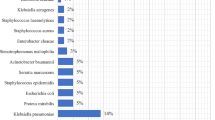

The pathogen related mortality rate and ratio of inappropriate antibiotic use are shown in Table 4. The most common pathogens in the study were E. coli (42 cases), K. pneumoniae (34 cases), MRSA (31 cases), and Burkholderia cepacia (23 cases). There was an outbreak of B. cepacia infection in the hospital between 2006 and 2007 [19]. The pathogens with mortality rates of more than 50% included MRSA, coagulase negative Staphylococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Viridans Streptococcus, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter spp., Hemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. For the species with at least 10 isolates in the study, cases infected with MRSA and Enterococcus faecalis had more than 80% chance to receive initial inappropriate antimicrobial therapy.

The most common inappropriate antibiotics used were cefazolin (57 cases, 43.5%), gentamicin (49 cases, 37.4%), and amoxicillin/clavulanate (35 cases 26.7%) (Table 5). For the other antibiotics, the rates were less than 10%.

The 30-day mortality rate and the analysis of factors associated with 30-day mortality were provided in the supplemental data (Table 6).

Discussion

This is the first report about inappropriate antibiotic use and outcomes of cases of bacteremia in a community hospital in Taiwan. Multiple drug resistant microorganisms were frequently encountered in the island nation [20, 21]. A high rate (59%) of initial inappropriate antibiotic use was observed, which is higher than most published studies [1, 3–11] and have led to the poor outcomes. We observed that nursing home-acquired BSI cases had the best prognosis when compared to the hospital-acquired and community-acquired BSI groups. Patients with ventilator support and patients requiring ICU care were the independent predictors for inhospital mortality. Patients with normal WBC counts had better survival outcome. Delayed appropriate antibiotic administration was found to be associated with a higher mortality rate.

One of the major causes of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy was the ignorance of the possibility of antimicrobial-resistant organisms causing the infections. Only 16.2% (36/222) of the BSI in the study was community-acquired. Not surprisingly, cefazolin, gentamicin and amoxicillin/clavulanate were the most commonly used initially and inappropriate antibiotics when most bacteremia episodes were healthcare associated. These drugs are frequently prescribed empirically in Taiwan due to the low cost. The regulations of the National Health Insurance (NHI) authority in Taiwan may have contributed to this prescription habit. Almost all hospitals in Taiwan are included in the reimbursement system of the NHI. The amount of reimbursement for each hospital is usually fixed every year, and the NHI refuses to reimburse the medical expenditure when the expense is higher than the fixed amount [22]. All hospitals are requested to reduce cost; therefore, newer antimicrobial agents those may cost more are restricted from being used as the initial antibiotics in some hospitals. Even though most antimicrobial resistance surveillance studies show that the major pathogens in Taiwan are resistant to the first or secondary generations of beta-lactams and aminoglycosides [20, 23, 24], cefazolin, gentamicin and amoxicillin/clavulanate are still common choices of empiric antibiotics in community hospitals. Our result alerts clinicians to notice impact on patient outcomes due to inappropriate antibiotic administration. It is also necessary to improve the physicians’ appropriate use of costlier antimicrobials when patients with sepsis are at high risk of acquiring drug resistant pathogens. Furthermore, the time taken to change to appropriate antibiotic therapy influenced the outcome of patients with BSI in this study, consistent with other reports [25–27]. It is therefore necessary to evaluate BSI cases from time to time and adjust the antibiotics accordingly. This is especially important for patients in a critical condition with septic shock status and confused consciousness, both of which were prognostic factors for poor outcomes.

We observed that the patients with BSI from the affiliated nursing home had better outcomes in multivariate analysis. Possible reasons for this are that the patients from the hospital affiliated nursing home had adequate medical information. These referral medical information includes hospitalization history, previous culture report, and recent infection sites, these could help the clinicians to estimate the risk of BSI cases to have multiple drug resistant pathogens, thereby allowing for a rapid intervention in the early phase of the BSI at the hospital, and help the clinicians to choose initial appropriate antibiotics.

In this study, old age and having ventilator support were the most important underlying conditions influencing survival (Table 1). These findings are similar to those previously reported by Lee et al., in which they showed that the impact of inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcomes of elderly patients with bacteremia was greater than that for younger adults [3]. A meta-analysis of BSI also revealed that inappropriate antimicrobial therapy significantly increased the odds of mortality in patients with ventilator support [9].

In this study, E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae were the three most common pathogens, which is similar to previous reports [6, 28] with the exception of B. cepacia bacteremia. However, there was an outbreak of B. cepacia due to contaminated multiple-dose heparin vials [19]. In addition, our study showed that MRSA led to the highest inappropriate antibiotic use (80.6%) and the highest in-hospital mortality rate (64.5%) among all pathogens. This suggests that local community hospital physicians may not recognize the risk factors and consequences of MRSA infections, which can be corrected by identifying the local risk factors for MRSA and continuing physician education.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a high mortality rate of patients with BSI was associated with a high rate of inappropriate antibiotic therapy in a community hospital in Taiwan. We observed a better prognosis in patients with BSI from a hospital-affiliated nursing home, whom were brought to the hospital with medical information. Efforts should be made to avoid the administration of inappropriate antibiotic therapy or delaying appropriate antibiotics administration in order to improve the outcomes of patients with BSI.

References

Laupland KB, Zygun DA, Doig CJ, Bagshaw SM, Svenson LW, Fick GH: One-year mortality of bloodstream infection-associated sepsis and septic shock among patients presenting to a regional critical care system. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31 (2): 213-219. 10.1007/s00134-004-2544-6.

Lueangarun S, Leelarasamee A: Impact of inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy on mortality of septic patients with bacteremia: a retrospective study. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012, 2012: 765205-

Lee CC, Chang CM, Hong MY, Hsu HC, Ko WC: Different impact of the appropriateness of empirical antibiotics for bacteremia among younger adults and the elderly in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013, 31 (2): 282-290. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.07.024.

Cortes JA, Garzon DC, Navarrete JA, Contreras KM: Impact of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy on patients with bacteremia in intensive care units and resistance patterns in Latin America. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2010, 42 (3): 230-234.

Laupland KB, Zygun DA, Davies HD, Church DL, Louie TJ, Doig CJ: Population-based assessment of intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections in adults: Incidence, risk factors, and associated mortality rate. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30 (11): 2462-2467. 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00010.

Lee CC, Lee CH, Chuang MC, Hong MY, Hsu HC, Ko WC: Impact of inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy on outcome of bacteremic adults visiting the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012, 30 (8): 1447-1456. 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.11.010.

Ibrahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH: The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest. 2000, 118 (1): 146-155. 10.1378/chest.118.1.146.

Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, Roberts D, Light B, Parrillo JE, Dodek P, Wood G, Simon D, Peters C, et al: Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009, 136 (5): 1237-1248. 10.1378/chest.09-0087.

Kuti EL, Patel AA, Coleman CI: Impact of inappropriate antibiotic therapy on mortality in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and blood stream infection: a meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2008, 23 (1): 91-100. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.08.007.

Khatib R, Saeed S, Sharma M, Riederer K, Fakih MG, Johnson LB: Impact of initial antibiotic choice and delayed appropriate treatment on the outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006, 25 (3): 181-185. 10.1007/s10096-006-0096-0.

Angkasekwinai N, Rattanaumpawan P, Thamlikitkul V: Epidemiology of sepsis in Siriraj Hospital 2007. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009, 92 (Suppl 2): S68-78.

Zaragoza R, Artero A, Camarena JJ, Sancho S, Gonzalez R, Nogueira JM: The influence of inadequate empirical antimicrobial treatment on patients with bloodstream infections in an intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003, 9 (5): 412-418. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00656.x.

Marschall J, Agniel D, Fraser VJ, Doherty J, Warren DK: Gram-negative bacteraemia in non-ICU patients: factors associated with inadequate antibiotic therapy and impact on outcomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008, 61 (6): 1376-1383. 10.1093/jac/dkn104.

McGregor JC, Rich SE, Harris AD, Perencevich EN, Osih R, Lodise TP, Miller RR, Furuno JP: A systematic review of the methods used to assess the association between appropriate antibiotic therapy and mortality in bacteremic patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 45 (3): 329-337. 10.1086/519283.

Wang FD, Chen YY, Chen TL, Liu CY: Risk factors and mortality in patients with nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Infect Control. 2008, 36 (2): 118-122. 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.02.005.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, et al: Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008, 36 (1): 296-327. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41.

Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town GI, Lewis SA, Macfarlane JT: Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003, 58 (5): 377-382. 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377.

Ginocchio CC: Role of NCCLS in antimicrobial susceptibility testing and monitoring. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002, 59 (8 Suppl 3): S7-11.

Yang CJ, Chen TC, Liao LF, Ma L, Wang CS, Lu PL, Chen YH, Hwan JJ, Siu LK, Huang MS: Nosocomial outbreak of two strains of Burkholderia cepacia caused by contaminated heparin. J Hosp Infect. 2008, 69 (4): 398-400. 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.03.011.

Lu PL, Liu YC, Toh HS, Lee YL, Liu YM, Ho CM, Huang CC, Liu CE, Ko WC, Wang JH, et al: Epidemiology and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections in the Asia-Pacific region: 2009–2010 results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012, 40 (Suppl): S37-43.

Lin JN, Chen YH, Chang LL, Lai CH, Lin HL, Lin HH: Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteremias in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2011, 6 (6): 547-555. 10.1007/s11739-011-0707-3.

Chang L, Hung JH: The effects of the global budget system on cost containment and the quality of care: experience in Taiwan. Health Serv Manage Res. 2008, 21 (2): 106-116. 10.1258/hsmr.2008.007026.

Chen YH, Lu PL, Huang CH, Liao CH, Lu CT, Chuang YC, Tsao SM, Chen YS, Liu YC, Chen WY, et al: Trends in the susceptibility of clinically important resistant bacteria to tigecycline: results from the Tigecycline In Vitro Surveillance in Taiwan study, 2006 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56 (3): 1452-1457. 10.1128/AAC.06053-11.

Kao CH, Kuo YC, Chen CC, Chang YT, Chen YS, Wann SR, Liu YC: Isolated pathogens and clinical outcomes of adult bacteremia in the emergency department: a retrospective study in a tertiary Referral Center. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011, 44 (3): 215-221. 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.023.

Erbay A, Idil A, Gozel MG, Mumcuoglu I, Balaban N: Impact of early appropriate antimicrobial therapy on survival in Acinetobacter baumannii bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009, 34 (6): 575-579. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.07.006.

Suppli M, Aabenhus R, Harboe ZB, Andersen LP, Tvede M, Jensen JU: Mortality in enterococcal bloodstream infections increases with inappropriate antimicrobial therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011, 17 (7): 1078-1083. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03394.x.

Leibovici L, Shraga I, Drucker M, Konigsberger H, Samra Z, Pitlik SD: The benefit of appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment in patients with bloodstream infection. J Intern Med. 1998, 244 (5): 379-386. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00379.x.

Valles J, Rello J, Ochagavia A, Garnacho J, Alcala MA: Community-acquired bloodstream infection in critically ill adult patients: impact of shock and inappropriate antibiotic therapy on survival. Chest. 2003, 123 (5): 1615-1624. 10.1378/chest.123.5.1615.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/500/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. We thank Malcolm Higgins who provided medical writing services on behalf of Asia Training Solutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CYJ, TCC and PLL conceived and designed the experiments; CJY and YCC contributed to the acquisition of data; TCC and HLC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; CJY and TCC drafted the manuscript; YMT, MSH, YHC and PLL revised it critically and approved the final version. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) used in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of its analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Chih-Jen Yang, Yu-Chieh Chung contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, CJ., Chung, YC., Chen, TC. et al. The impact of inappropriate antibiotics on bacteremia patients in a community hospital in Taiwan: an emphasis on the impact of referral information for cases from a hospital affiliated nursing home. BMC Infect Dis 13, 500 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-500

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-500