Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is endemic in China; perinatal transmission is the main source of chronic HBV infection. Simultaneous administration of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and hepatitis B vaccine is highly effective to prevent perinatal transmission of HBV; however, the effectiveness also depends on full adherence to the recommended protocols in daily practice. In the present investigation, we aimed to identify gaps in immunoprophylaxis of perinatal transmission of HBV between recommendations and routine practices in Jiangsu Province, China.

Methods

Totally 626 children from 6 cities and 8 rural areas across Jiangsu Province, China, born from February 2003 to December 2004, were enrolled; 298 were born to mothers with positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and 328 were born to HBsAg-negative mothers. Immunoprophylactic measures against hepatitis B were retrospectively reviewed for about half of the children by checking medical records or vaccination cards and the vaccine status was validated for most of children.

Results

Of 298 children born to HBV carrier mothers, 11 (3.7%) were HBsAg positive, while none of 328 children born to non-carrier mothers was HBsAg positive (P < 0.01). The rates of anti-HBs ≥ 10 mIU/ml in children of carrier and non-carrier mothers were 69.5% and 69.2% respectively (P = 0.95). The hepatitis B vaccine coverage in two groups was 100% and 99.4% respectively (P = 0.50), but 15.1% of HBV-exposed infants did not receive the timely birth dose. Prenatal HBsAg screening was performed only in 156 (52.3%) of the carrier mothers. Consequently, only 112 (37.6%) of HBV-exposed infants received HBIG after birth. Furthermore, of the 11 HBV-infected children, only one received both HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine timely, seven missed HBIG, two received delayed vaccination, and one missed HBIG and received delayed vaccination.

Conclusions

There are substantial gaps in the prevention of perinatal HBV infection between the recommendations and routine practices in China, which highlights the importance of full adherence to the recommendations to eliminate perinatal HBV infection in the endemic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem worldwide, particularly in Asia and Africa, and Asian communities in low or high HBV endemic areas [1, 2]. Prevention of perinatal HBV infection from HBV carrier mothers to their infants is critical to eliminate chronic hepatitis B since as high as 90% of the neonatal infections will become chronically infected. Simultaneous administration with one dose (0.5–1 ml, 100–200 IU) of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) within 12 hours after birth and three doses of hepatitis B vaccine on a 0-, 1-, and 6-month schedule, which has been adopted by many countries as well as China as the recommended immunoprophylaxis for infants born to HBV carrier mothers, is highly effective to prevent perinatal HBV infections [3–5]. Up to 2008, 177 countries included the hepatitis B vaccine into their national infant immunization programs [6]. The Chinese government formally integrated hepatitis B vaccine into its Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in 2002, and since then all newborns in China may receive three doses of hepatitis B vaccine without charge [7, 8].

The protective effect of a vaccine is not only dependent on its quality, but also on full adherence to the recommended protocols in daily practice. In developed countries, the vaccination schedule against hepatitis B has been followed well in the routine practices and the protective efficiency was 90–100% in infants born to HBV carrier mothers, as high as the protective rates achieved in the clinical trials [9–12]. In developing countries like China, where HBV infection is highly endemic, however, the protective efficiency in daily practice has been less studied. In the present study, we surveyed the administration of hepatitis B vaccine and HBIG and measured the serologic markers in infants born to HBV carrier mothers based on the pregnant women population in Jiangsu province, China, to determine whether there are gaps in the immunoprophylaxis against perinatal HBV transmission between national recommendations and the routine practices after the integration of hepatitis B vaccine into the EPI of China.

Methods

Study design and subjects

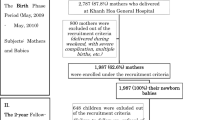

During August 2002 to July 2004, serum samples from 19 904 pregnant women aged 20–42 years, at 15–20 weeks of gestation, from 6 cities (urban) and 8 counties (rural area) across Jiangsu Province, China, were collected in a study on the provincial prevalence of birth defects [13]. The samples were stored at −30°C. These pregnant women had been selected to represent the pregnant women population in Jiangsu and all delivered their infants in hospitals. Jiangsu Province is located in the east of China, and is one of the six financially prosperous provinces in China and has the densest population with more than 76 million inhabitants. There are approximately 500 000 live births per year. Recently, we retrospectively measured the HBV serologic markers in the 6398 sera, which were randomly selected from above samples, and 429 (6.7%) were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) [14]. Of the 429 HBsAg positive sera, 10 were negative for antibody against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) and either hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) or anti-HBe. The positivity of HBsAg in these 10 samples was validated by retesting with Architect HBsAg Reagents (Abbott, North Chicago, USA) and by detection of HBV DNA [14]; we speculated that these 10 women were in the incubation period of HBV infection when the sera were collected. Thus, we excluded these 10 women from the study and planned to follow up the children of 419 HBsAg positive women, of whom 125 (29.8%) were also positive for HBeAg [14]. Because of the “one family one child policy” in China, the target population was the 419 children born from February 2003 to December 2004 (Figure 1). As control subjects, 453 children born to HBsAg negative mothers in the same areas and same period of time were randomly selected (Figure 1).

During October 2009 and March 2010, we invited these mothers and their children to participate in the present investigation as an “add-on” part of the project on the provincial prevalence of birth defects [13]. Each attending mother was asked to complete a questionnaire, which included demographic data of the mother and her child, screening for HBsAg during pregnancy, and use of hepatitis B vaccine and HBIG in the child. Nearly half of the HBsAg screening in pregnant women and the HBIG administration in infants were validated by checking the hospital discharge records. The use of hepatitis B vaccine was evidenced in 83.7% children by the vaccination record cards. Furthermore, ~3 ml of blood was collected from each child after obtaining the consent from the child’s mother.

This study followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institutional review boards of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital and Jiangsu Family Planning Institute. The pregnant women consented to participate in the birth defect study conducted from August 2002 to July 2004 [13] and their serum samples were used in this study; the mothers consented to be interviewed and consented to their children's participation in this follow-up study.

Laboratory procedures

All serum samples were tested by commercial ELISA kits for the presence of HBsAg, antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs), and anti-HBc. HBsAg was tested with an ELISA kit (Huakang Biotech, Shenzhen, China), and anti-HBs and anti-HBc were quantitatively tested with microparticle enzyme immunoassay (AxSYM AUSAB, Abbott, North Chicago, USA). Quantitative levels of anti-HBs were expressed in international units.

Definitions and statistical analysis

HBV infection was defined by the presence of HBsAg. The presence of anti-HBc in the absence of HBsAg represented resolved HBV infection. Timely vaccination referred to receipt of the first dose of the vaccine within 24 hours after birth.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Statistical comparisons of continuous variables between maternal HBsAg positive and negative groups were analyzed by t-test. A χ 2 test was used to analyze and compare categorical data. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of routine hepatitis B immunization on the prevalence of HBV in infants of HBsAg positive mothers

Of the 419 invited mothers with positive HBsAg, 298 (71.1%) mothers and their children participated in the study, while 328 (72.4%) of the 453 invited mothers who were negative for HBsAg and their children attended the investigation (Figure 1); the follow-up rates were comparable in these two groups (P > 0.05). Additionally, the follow-up rate of children born to HBV carrier mothers with positive HBeAg was also similar to that of children of carrier mothers with negative HBeAg (72.0% vs. 70.7%, Figure 1). The demographic data, vaccination coverage, status of HBV infection, and anti-HBs responses in children are shown in Table 1. Almost all infants in the both groups were vaccinated and the positive rates of anti-HBs were comparable. Of the children born to HBsAg positive mothers, 11 (3.7%) were HBsAg positive, demonstrating the HBV infection, and 16 (5.4%) were HBsAg negative but anti-HBc positive, indicating past resolved infection, whereas none of the children born to HBsAg negative mothers was infected with HBV and only 0.9% had the resolved infection.

Administration of immunoprophylaxis in infants of HBsAg positive mothers

Since recommended immunoprophylaxis against hepatitis B in infants born to HBsAg positive mothers requires the timely use of hepatitis B vaccine and HBIG, we particularly paid attention to collecting the data about the preventive measures used in the routine practices (Table 2). Although prenatal HBsAg screening is recommended for all pregnant women in China, the test was not done in nearly a third of the pregnant women in cities and more than half in rural areas. Consequently, only 37.6% of the HBV-exposed infants received HBIG after birth, and the use of HBIG in HBV-exposed infants was less frequently in rural areas than in cities (55.7% vs. 32.0%, P <0.001). In other words, 62.4% of the infants born to HBV carrier mothers were not administered with HBIG in Jiangsu Province from February 2003 to December 2004. This was a substantial gap in the prevention of HBV infection. Additionally, the first dose of the vaccine was delayed in 15.1% of the HBV-exposed infants.

Inadequate implementation of the immunoprophylaxis responsible for most HBV infection in children

Of the 298 children born to HBV carrier mothers, 11 were infected with HBV and 16 experienced resolved infections (Table 1). To clarify the factors responsible for the infections, we analyzed the HBeAg status in their mothers and the immunoprophylactic measures used in these children. All 11 children infected with HBV and 12 of 16 children with the resolved infection were born to HBeAg positive mothers. These results are in agreement with the previous reports that children born to HBV carrier mothers with positive HBeAg are much more frequently to be infected than those born to HBeAg negative HBV carrier mothers [15, 16]. On the other hand, of the 11 children infected with HBV, only one received timely administration of both HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine, and 10 others did not receive HBIG or received delayed hepatitis B vaccine (Table 3). Of the 16 children with the resolved infections, 9 were not administered with HBIG and one was given the first dose of vaccine 40 days after birth (Table 3). The results demonstrated that the infections in children born to HBV carrier mothers were mostly attributed to the inadequate implementation of the immunoprophylaxis.

Discussion

In the present population-based study, we found that, although most children of HBV carrier mothers were protected against chronic HBV infection after the introduction of the universal immunization, there were considerable gaps in the immunoprophylaxis of perinatal HBV infection between the routine practices and national recommendations in China. Such gaps may also exist in other developing countries since only 23.7% of the 8–10-year-old children in East Java, Indonesia, were anti-HBs positive after introduction of universal vaccination program [17] and the vaccine coverage in remaining quilombo communities in Central Brazil is suboptimal [18]. Therefore, the significance of full compliance with the recommended procedures to prevent perinatal HBV transmission should be emphasized in China as well as other developing countries.

Prenatal HBsAg screening has been recommended in all pregnant women in China since the late of 1980s, however, the actual screening rate in the present investigation was only 52.3%, far from the rates of 90–99% in developed countries [19–22]. The gap is particularly substantial in the rural areas as only 46.9% of pregnant women underwent the prenatal screening. Since all investigated women had experienced prenatal examinations and delivered their children in hospitals, we considered that the low HBsAg screening rate was largely attributed to the health care providers’ unawareness of the importance of the screening. We can imagine that the adherence to preventive measures may be worse in infants of mothers delivering at home in remote rural areas of China. Thus, more intensive information about the importance of preventing mother-to-infant transmission of HBV should be provided to health care providers as well as pregnant women to increase prenatal HBsAg screening.

The administration of prophylactic measures against hepatitis B in HBV-exposed infants was far from optimal in China. Although all the infants received hepatitis B vaccine, the birth dose was delayed in 15.1% of the newborns and three doses were not completed in 7% of them. Furthermore, HBIG was used only in 37.6% of the high risk infants. The untimely use of the birth dose vaccine was apparently due to the oversight of the health care providers since it is recommended that the birth dose vaccine be given within 24 hours after birth. The low usage of HBIG might be caused by several reasons, first, unavailability of HBIG in some hospitals because these hospitals do not have specific policies on preventing perinatal HBV infection; second, the lack of knowledge on the standard prophylaxis in the health care providers; third, neglecting the use of HBIG by some health care providers since the implementation of universal vaccination against hepatitis B, whatever the status of the mother, might have been confusing for those not specialized in HBV infection; and fourth, also most important, unknown HBsAg status in the pregnant women before birth because of the low rate of prenatal HBsAg screening. Unlike the recommendation in USA, in which infants born to women with unknown HBsAg status are administered with both HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine [23], the policy in China is that only infants born to known HBV carrier mothers receive passive-active immunoprophylaxis.

Although only 3.7% of HBV-exposed infants in this investigation were infected with HBV, our findings indicate that there is still a room to increase the protection conferred by the vaccination against hepatitis B, because the failure of the protection is largely due to the inappropriate administration of the recommended prophylactic procedures in the routine practices (Table 3). Additionally, recent studies show that in developed countries, 98–100% of the HBV-exposed infants were protected against the chronic infection after passive-active immunoprophylaxis had been strictly followed [9–12]. This highlights the importance of the full adherence to the standard immunoprophylaxis in the prevention of perinatal HBV infections.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, the overall follow-up rate (71.1%) in HBV-exposed children was not high. However, it is less likely that the HBsAg positive rate in the children was biased due to this reason, since a comparable follow-up rate (72%) in children born to HBeAg positive carrier mothers, whose infants are more prone to be infected, was achieved. Second, the perinatal HBV infection in this study was examined at the age of 5–7 years, rather than at 12 months old. However, spontaneous HBsAg loss in children perinatally infected is very low [24], and novel HBV infection in vaccinated children rarely occurs [25]. Thus, the positive rate of HBsAg in children at ages of 5–7 years whose mothers are infected with HBV may essentially represent the perinatal infection. Third, the measures in the routine practices investigated in this survey were implemented during 2002–2004 and not all the data on screening for HBsAg in pregnant women and administration of HBIG in infants were validated by medical records; the current status of services for infants of HBV carrier mothers could be improved. However, a recent preliminary survey in the prevention of perinatal HBV transmission among obstetric and gynecological medical staffs in China showed that there is insufficient training in the application of immunoprophylaxis, particularly in rural areas (unpublished data), suggesting there is a big room to improve the immunoprophylaxis against hepatitis B. On the other hand, there are two strengths in this study. One is that the study subjects were from 14 areas across Jiangsu; the data should be superior to those from a single center study. The other is that we conducted this study as the third party in a more objective manner.

Although the results in this study were derived from a province in China, we consider that the identified gaps also exist in most areas of China as Jiangsu is one of the six financially prosperous regions among the 31 provinces in Mainland China. We also consider that the data of the present study may basically reflect the scenario in some developing countries like China. Thus, a national organization dedicated to educating health care providers in delivery units and delivery hospitals about the knowledge of preventing perinatal HBV infection will be critical for filling the gaps.

Conclusions

Despite the availability of effective immunoprophylaxis in the prevention of perinatal transmission of HBV for more than 20 years, there are substantial gaps between the recommendations and routine practices in China, which highlights the importance of full adherence to the recommendations to eliminate perinatal HBV infections in the endemic regions.

Abbreviations

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBIG:

-

Hepatitis B immune globulin

- HBeAg:

-

Hepatitis B e antigen

- Anti-HBs:

-

Antibody against HBsAg

- Anti-HBc:

-

Antibody against hepatitis B core antigen

- EPI:

-

Expanded program on immunization.

References

Mahamat A, Louvel D, Vaz T, Demar M, Nacher M, Djossou F: High prevalence of HBsAg during pregnancy in Asian communities at Cayenne Hospital, French Guiana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 83: 711-713. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0727.

Rein DB, Lesesne SB, Leese PJ, Weinbaum CM: Community-based hepatitis B screening programs in the United States in 2008. J Viral Hepat. 2010, 17: 28-33. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01165.x.

McMahon BJ, Bulkow LR, Singleton RJ, Williams J, Snowball M, Homan C, Parkinson AJ: Elimination of hepatocellular carcinoma and acute hepatitis B in children 25 years after a hepatitis B newborn and catch-up immunization program. Hepatology. 2011, 54: 801-807. 10.1002/hep.24442.

Ni YH, Huang LM, Chang MH, Yen CJ, Lu CY, You SL, Kao JH, Lin YC, Chen HL, Hsu HY, Chen DS: Two decades of universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan, impact and implication for future strategies. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 1287-1293. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.055.

Chen DS: Hepatitis B vaccination, The key towards elimination and eradication of hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009, 50: 805-816. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.002.

World Health Organization: Hepatitis B vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009, 84: 405-420.

Zhou YH, Wu C, Zhuang H: Vaccination against hepatitis B, the Chinese experience. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009, 122: 98-102.

Lu FM, Zhuang H: Prevention of hepatitis B in China, achievements and challenges. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009, 122: 2925-2927.

Heininger U, Vaudaux B, Nidecker M, Pfister RE, Posfay-Barbe KM, Bachofner M, Hoigne I, Gnehm HE: Evaluation of the compliance with recommended procedures in newborns exposed to HBsAg-positive mothers, a multicenter collaborative study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010, 29: 248-250. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181bd7f89.

Plitt SS, Somily AM, Singh AE: Outcomes from a Canadian public health prenatal screening program for hepatitis B, 1997–2004. Can J Public Health. 2007, 98: 194-197.

Bracciale L, Fabbiani M, Sansoni A, Luzzi L, Bernini L, Zanelli G: Impact of hepatitis B vaccination in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers, a 20-year retrospective study. Infection. 2009, 37: 340-343. 10.1007/s15010-008-8252-3.

Stroffolini T, Bianco E, Szklo A, Bernacchia R, Bove C, Colucci M, Cristina Coppola R, D'Argenio P, Lopalco P, Parlato A, Ragni P, Simonetti A, Zotti C, Mele A: Factors affecting the compliance of the antenatal hepatitis B screening programme in Italy. Vaccine. 2003, 21: 1246-1249. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00439-5.

Zhou J, Hu Y, Liu Q, Chen Q, Xu B, The Group of Birth Defects Intervention Project in Jiangsu Province: Analysis of birth defects based on population survey in Jiangsu Province. Jiangsu Medical Journal. 2007, 33: 1218-1220. in Chinese

Zhang S, Li RT, Wang Y, Liu Q, Zhou YH, Hu Y: Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen among pregnant women in Jiangsu, China, 17 years after introduction of hepatitis B vaccine. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010, 109: 194-197. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.002.

Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, Heron LG, Maley MW, Ayres A, Locarnini SA, Levy MT: Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus, an Australian experience. Med J Aust. 2009, 190: 489-492.

Song YM, Sung J, Yang S, Choe YH, Chang YS, Park WS: Factors associated with immunoprophylaxis failure against vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus. Eur J Pediatr. 2007, 166: 813-818. 10.1007/s00431-006-0327-5.

Utsumi T, Yano Y, Lusida MI, Amin M, Soetjipto , Hotta H, Hayashi Y: Serologic and molecular characteristics of hepatitis B virus among school children in East Java, Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 83: 189-193. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0589.

Motta-Castro AR, Gomes SA, Yoshida CF, Miguel JC, Teles SA, Martins RM: Compliance with and response to hepatitis B vaccination in remaining quilombo communities in Central Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009, 25: 738-742. 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000400004.

Bascom S, Miller S, Greenblatt J: Assessment of perinatal hepatitis B and rubella prevention in New Hampshire delivery hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005, 115: e594-e599. 10.1542/peds.2004-2057.

Liu CY, Chang NT, Chou P: Seroprevalence of HBV in immigrant pregnant women and coverage of HBIG vaccine for neonates born to chronically infected immigrant mothers in Hsin-Chu County, Taiwan. Vaccine. 2007, 25: 7706-7710. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.056.

Papaevangelou V, Hadjichristodoulou C, Cassimos D, Theodoridou M: Adherence to the screening program for HBV infection in pregnant women delivering in Greece. BMC Infect Dis. 2006, 6: 84-10.1186/1471-2334-6-84.

Spada E, Tosti ME, Zuccaro O, Stroffolini T, Mele A, Collaborating Study Group: Evaluation of the compliance with the protocol for preventing perinatal hepatitis B infection in Italy. J Infect. 2011, 62: 165-171. 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.11.014.

Willis BC, Wortley P, Wang SA, Jacques-Carroll L, Zhang F: Gaps in hospital policies and practices to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus. Pediatrics. 2010, 125: 704-711. 10.1542/peds.2009-1831.

Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F: Natural history of chronic hepatitis B, special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008, 48: 335-352. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011.

Chen CY, Hsu HY, Liu CC, Chang MH, Ni YH: Stable seroepidemiology of hepatitis B after universal immunization in Taiwan, A 3-year study of national surveillance of primary school students. Vaccine. 2010, 28: 5605-5608. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.029.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/221/prepub

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Jihong Sun, Ms. Fengxiang He, and members in Family Planning Institutes of Xuzhou, Tongshan, Ganyu, Lianyungang, Sheyang, Baoying, Qidong, Yangzhou, Liuhe, Zhenjiang, Liyang, Wuxi, Wujiang, and Nanjing Xuanwu for blood sampling by venepuncture and assistance in collecting relevant information.

This study was supported by a Grant (ZKM06050 to YHZ) for the Development of Medical Sciences from the Health Bureau of Nanjing City, by Special Grants for Leading Principal Investigators (LJ200628 to YH), for Principal Investigators (RC2007005 to YHZ), and for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (XK200709 to YH) from Health Department of Jiangsu Province, by Natural Science Grant (BK2008501 to QL) from Jiangsu Science and Technology Department, and by a Research Grant (2011208) from Population Family Planning Commission of Jiangsu Province, and by a Grant (2010CB945104 to YH) from National Key Basic Research Project (973 Planning), China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

YH and SZ participated in the design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of the data; CL and QL performed the laboratory procedures. SZ performed the statistical analysis. YHZ conceived of and designed the study, directed its implementation, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yali Hu, Shu Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Zhang, S., Luo, C. et al. Gaps in the prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus between recommendations and routine practices in a highly endemic region: a provincial population-based study in China. BMC Infect Dis 12, 221 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-221

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-221