Abstract

Background

Nosocomial infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa presenting resistance to beta-lactam drugs are one of the most challenging targets for antimicrobial therapy, leading to substantial increase in mortality rates in hospitals worldwide. In this context, P. aeruginosa harboring acquired mechanisms of resistance, such as production of metallo-beta-lactamase (MBLs) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) have the highest clinical impact. Hence, this study was designed to investigate the presence of genes codifying for MBLs and ESBLs among carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolated in a Brazilian 720-bed teaching tertiary care hospital.

Methods

Fifty-six carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strains were evaluated for the presence of MBL and ESBL genes. Strains presenting MBL and/or ESBL genes were submitted to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for genetic similarity evaluation.

Results

Despite the carbapenem resistance, genes for MBLs (bla SPM-1 or bla IMP-1) were detected in only 26.7% of isolates. Genes encoding ESBLs were detected in 23.2% of isolates. The bla CTX-M-2 was the most prevalent ESBL gene (19.6%), followed by bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 detected in one isolate each. In all isolates presenting MBL phenotype by double-disc synergy test (DDST), the bla SPM-1 or bla IMP-1 genes were detected. In addition, bla IMP-1 was also detected in three isolates which did not display any MBL phenotype. These isolates also presented the bla CTX-M-2 gene. The co-existence of bla CTX-M-2 with bla IMP-1 is presently reported for the first time, as like as co-existence of bla GES-1 with bla IMP-1.

Conclusions

In this study MBLs production was not the major mechanism of resistance to carbapenems, suggesting the occurrence of multidrug efflux pumps, reduction in porin channels and production of other beta-lactamases. The detection of bla CTX-M-2, bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 reflects the recent emergence of ESBLs among antimicrobial resistant P. aeruginosa and the extraordinary ability presented by this pathogen to acquire multiple resistance mechanisms. These findings raise the concern about the future of antimicrobial therapy and the capability of clinical laboratories to detect resistant strains, since simultaneous production of MBLs and ESBLs is known to promote further complexity in phenotypic detection. Occurrence of intra-hospital clonal dissemination enhances the necessity of better observance of infection control practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for a large spectrum of invasive diseases in healthcare settings, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections and bacteremia [1]. For such infections, antimicrobial therapy may become a difficult task, because Pseudomonas aeruginosa is naturally resistant to many drugs, and presents a remarkable ability to acquire further resistance mechanisms to multiple classes of antimicrobial agents, even during the course of a treatment [2]. In this context, infections by P. aeruginosa presenting acquired resistance to beta-lactam drugs are considered one of the most challenging targets for antimicrobial therapy [3], being responsible for high rates of therapeutic failure, increase in mortality, morbidity, and in overall cost of treatment [4–6].

The Ambler’s class B beta-lactamases (metallo-beta-lactamases – MBLs) and class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) are acquired resistance determinants that present high clinical impact [7, 8]. These enzymes, usually codified by genes associated with mobile genetic elements, are matter of major concern with regard to the future of antimicrobial chemotherapy because of its remarkable dissemination capability [9].

MBLs such as IMP, VIM, SPM, GIM and AIM represent the leading acquired mechanism of resistance to beta-lactams in P. aeruginosa. These enzymes hydrolyze the majority of beta-lactam drugs [10] and compromise clinical utility of carbapenems, the most potent agents for treating severe infections caused by multidrug resistant strains [11]. More recently, appearance of ESBLs such as TEM, SHV, CTX-M, BEL, PER, VEB, GES, PME and OXA-type beta-lactamases has become an emergent public health problem, since these enzymes confer resistance to at least all expanded spectrum cephalosporins and compromise efficiency of ceftazidime, an important antibiotic regimen for P. aeruginosa[12–14].

For the establishment of the appropriate antimicrobial therapy and for assessment and control of the spread of drug resistant P. aeruginosa, the molecular detection and surveillance of resistance genes is becoming increasingly important [15, 16]. Despite of this, epidemiological data reporting the prevalence of MBL and ESBL producing P. aeruginosa is sparse, due to the inexistence of standardized methods for phenotypic detection of ESBL and MBL production [7, 17] and the complexity for the implementation of PCR based methods in the routine of clinical laboratories [17]. In order to overcome this difficulty, a number of commercial rapid molecular tests are being developed that identify pathogens and the presence of genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance [18, 19]. The association of such new technologies with current classical methods may improve the ability of clinical laboratories to provide accurate and fast results that will impact on patient care.

Hence, this study was performed to investigate the carriage of genes codifying MBLs and ESBLs by P. aeruginosa isolated from patients admitted to a Brazilian 720-bed teaching tertiary care hospital. Despite the high rates of carbapenem resistance, genes for MBLs production were not observed in the majority of the isolates. Notably ESBLs codifying genes bla CTX-M-2, bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 were detected in several strains, and the coexistence of bla CTX-M-2 with bla IMP-1, and bla GES-1 with bla IMP-1 in P. aeruginosa was observed, and is presently reported for the first time. These findings underline the emergence of class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among P. aeruginosa.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

In this study were included a total of 56 P. aeruginosa isolates resistant to ceftazidime, imipenem and/or meropenem, nonrepetitively obtained from patients admitted to a teaching hospital in São Paulo State, Brazil, over a period between June to December 2009. Isolates were obtained from specimens originated from urinary tract, respiratory tract, bloodstream and soft tissue. Clinical specimens were collected in intensive care units, clinical and surgical wards as well as from outpatients as a standard care procedure and were stored for this work. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board from our institution (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa – FAMERP) under protocol # 3131/2009.

Susceptibility testing and phenotypic detection of MBL production

Antimicrobial susceptibility to aztreonam, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and polymyxin B were determined by the disk diffusion method, following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute recommendations [20]. Phenotypic detection of MBLs was performed by double-disc synergy test (DDST) using the 2-mercaptopropionic acid as a MBL inhibitor [17].

Genotypic detection of MBL and ESBL genes

Specific primers and protocols were used to detect and sequence bla TEM bla SHV bla CTX-M bla GES bla KPC bla IMP and bla VIM[17, 21–24]. The detection and sequencing of bla SPM-1 was performed using primers previously described [25] and also others specifically designed for this study using DS Gene 2.0 Software (Accelrys, USA). PCR products were purified in ethanol according to previously described methodology [26] and subjected to direct sequencing with the ABI PRISM 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The products were aligned with Accelrys Gene 2.0 (Accelrys Software Inc. 2006). Database similarity searches were run with BLAST at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Molecular typing

Genetic relatedness was evaluated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using SpeI (Fermentas Life Sciences, MD, EUA) with a CHEF-DR II apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, EUA) as described elsewhere [27]. BioNumerics software (Applied Maths) was used for dendrogram construction and clustering, based on the band-based Dice’s similarity coefficient and using the unweighted pair group method (UPGMA) using arithmetic averages. Isolates were considered to belong to the same cluster when similarity coefficient was 90% [28]. The visual Tenover criteria were also applied [29].

Results

A total of 80.3% (45/56) of isolates were resistant to the combination piperacillin/tazobactam, 62.5% (35/56) to aztreonam, 78.6% (44/56) to ceftazidime, 96.4% (54/56) to cefepime, 96.4% (54/56) to imipenem, 75.0% (42/56) to meropenem, 51.8% (29/56) to amikacin, 82.1% (46/56) to gentamicin, 78.6% (44/56) to ciprofloxacin and 85.7% (48/56) to levofloxacin. All isolates showed sensitivity to polymyxin B (data not shown). Thirteen isolates (23.2%) presented MBL phenotype by the DDST (Table 1).

The prevalence of isolates harboring MBL genes was 30.3% (17/56). Ten (17.8%) presented the bla SPM-1 gene, and the bla IMP-1 was detected in seven isolates (12.5%). In all thirteen isolates presenting MBL phenotype by DDST, bla SPM-1 or bla IMP-1 was detected. In addition, the bla IMP-1 gene was also detected in three isolates which did not display any MBL phenotype. These isolates also presented the bla CTX-M-2 gene (Table 1). No bla VIM type was detected.

Genes encoding ESBLs were detected in 23.2% (13/56) of the isolates. The bla CTX-M-2 was detected in eleven isolates (19.6%), bla GES-1 was detected in one and bla GES-5 was detected in one isolate. Co-existence of bla CTX-M-2 with bla IMP-1 was detected in three isolates and bla GES-1 with bla IMP-1 in one isolate (Table 1). No bla TEM and bla SHV types were detected GenBank Accession Numbers are provided in Supplemental Material (Additional File 1).

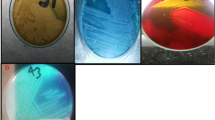

The degree of relatedness among the Pseudomonas aeruginosa harboring MBL and ESBL genes was assessed by PFGE analysis (Figure 1). Eight isolates harboring bla SPM-1 were typed, and by visual inspection all were considered closely related, presenting up to three bands of difference. According to PFGE profiles these isolates were grouped within three clusters (A, B and C). Similarity between cluster A and B was of 89.1%. Clusters A and B presented 87.6% of similarity with cluster C.

Dendrogram of PFGE patterns presented by carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa included in this study. ER, emergence room; E-ICU, emergence intensive care unit; G-ICU, geral intensive care unit; S-ICU, semi-intensive care unit; C-ICU, cardiology intensive care unit; P-ICU, pediatrics intensive care unit, N-ICU, neonatal intensive care unit N-Dep, neurology department; C-Dep, cardiology department; SC, surgical ward, CI, cancer institute.

The P. aeruginosa harboring bla IMP-1 were distributed among five different clusters (E to I), and isolates harboring bla CTX-M-2 in three clusters (D, E, H). Cluster E included seven isolates presenting similarity of at least 92.3%. Within this cluster, four isolates exhibited bla CTX-M-2, one exhibited bla IMP-1 and two isolates exhibited bla IMP-1 and bla CTX-M-2 simultaneously. One isolate harboring bla CTX-M-2 was placed in cluster D, four isolates harboring bla IMP-1 were placed in clusters F, G, H and I, and one isolate exhibiting bla IMP-1 and bla CTX-M-2 simultaneously was placed in cluster H. Isolates harboring bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 could not be typed.

Discussion

The pattern of multidrug resistance presented by the P. aeruginosa included in this study was expected, since carbapenem resistant strains exhibit a broad-spectrum resistance to beta-lactams and often present resistant phenotype to additional classes of drugs. Also, acquired ESBL and MBL genes typically group with other drug resistance determinants in the variable region of multi-resistance integrons [30–32]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa isolated in Latin America, including Brazil, are reported as presenting the higher rates of antibiotic resistance [33]. P. aeruginosa strains resistant to polymyxins were not detected in this study. However, this result should be confirmed by a dilution method, considering that the disc diffusion technique, commonly used in clinical microbiology laboratories is reported to be an unreliable method for evaluating the susceptibility to polymyxins because these drugs diffuse poorly into agar [34].

In this study MBL genes were detected in 26.7% of isolates, indicating that despite the increasing significance of MBL production among P. aeruginosa, this was not the main mechanism of resistance to imipenem and/or meropenem. This reality was previously reported in another Brazilian hospital [35]. In fact, resistance to carbapenems in P. aeruginosa is due not only to the production of carbapenemases, but also to different mechanisms such as upregulation of multidrug efflux pumps, cell wall mutations leading to reduction in porin channels and production of different beta-lactamases [1, 11]. Expression of these mechanisms, isolated or in combination, may cause variation in rates of resistance to imipenem and meropenem, observed in this study [5]. The twelve isolates presenting MBL phenotype by the DDST harbored MBL genes (bla SPM-1 or bla IMP-1), confirming the efficacy of this method for the phenotypic detection of MBL producing strains [17, 36].

Diversity of MBL among P. aeruginosa varies by regional areas [37]. In this study the 17.5% of the carbapenem resistant isolates presented the bla SPM-1 gene, and bla IMP-1 was detected in 10.5% of the isolates. SPM-1 is in fact the most prevalent MBL in Brazil [38]. In a different way, IMP-1 producing strains have been reported in various Brazilian hospitals in diverse rates [35, 39, 40].

Molecular typing by PFGE showed a wide diversity of patterns. All isolates exhibiting bla SPM-1, a chromosomally located gene [41, 42] presented high coefficient of similarity and closely related PFGE patterns, suggesting a close genetic relationship. This is in agreement with previously described data, showing that the Brazilian SPM-1-producing P. aeruginosa are probably derived from a single clone [43]. According to the same study, even a recent genomic variety recently observed among various SPM-1-producing P.aeruginosa isolates is result of the accumulation of mutations along the time.

Occurrence of bla IMP-1 in P. aeruginosa described in this study is likely a result of gene horizontal transferring, since isolates harboring bla IMP-1 belong to five different clusters. Dissemination of bla IMP among Gram-negative pathogens is mediated by mobile elements of DNA, explaining why the same gene might be detected in different strains. The genes for IMP enzymes are often carried as cassettes within integrons, which facilitate recombination and facilitate rapid horizontal transferring [44–46].

The coexistence of bla IMP-1 with bla CTX-M-2 in P. aeruginosa was, at the best of our knowledge, detected for the first time. Interestingly, the three isolates presenting this combination of genes did not provide a positive result in the DDST test, and were the only bla IMP-1 carriers in which MBL phenotypic detection was unsuccessful. Since ceftazidime is poorly hydrolyzed by CTX-M-2 [31], we could not assume that inactivation of this antimicrobial, used as substrate, may have been responsible for this result. However, simultaneous production of MBLs and ESBLs by the same strain is known to promote further complexity in phenotypic detection [7, 47, 48]. This result emphasizes the importance of molecular methods for the identification of antimicrobial resistance in multidrug resistant pathogenic bacteria. In this matter, detection of resistance genes by PCR may provide clinically relevant information with positive impact in patient prognosis [18].

The detection of bla CTX-M-2 bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 in this study reflects the recent emergence of ESBLs in P. aeruginosa as result of the great dissemination capability exhibited by these genes that occur mostly as part of integron structures on mobile transmissible genetic elements [49–52]. Location of bla CTX-M-2 in P. aeruginosa is believed to be a result of their transfer from Enterobacteriaceae[51]. Recently, a high prevalence of K. pneumoniae harboring bla CTX-M-2 in the same hospital was reported [21], and this may have been the reservoir for horizontal transmission.

Regarding GES-type ESBLs, although these enzymes are not considered as primary β-lactamases in P. aeruginosa, acquisition in conditions of antimicrobial pressure may be beneficial [52]. The bla GES-1 was detected in co-existence with bla IMP-1, and bla GES-5 was detected in a strain resistant to imipenem and meropenem, but presenting no MBL phenotype. Considering that GES-5 presents enhanced hydrolyse activity against carbapenems [10], it is likely that GES-5 production contributed for the carbapenem resistance in this isolate.

Conclusion

Production of MBLs was not the main mechanism of resistance to carbapenems among the studied strains. However, IMP-1 is disseminated among different strains of carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa, and intra-hospital spread of SPM-1 producing strains was observed. The detection of bla CTX-M-2, bla GES-1 and bla GES-5 and the unique coexistence of bla CTX-M-2 with bla IMP-1 and bla GES-1 with bla IMP-1 exemplify the extraordinary ability presented by P. aeruginosa to acquire multiple resistance mechanisms.

Clonal dissemination of multidrug resistant P. aeruginosa within the hospital was inferred by the observation of strains presenting the identical PFGE profiles infecting different patients, and the occurrence of clonal dissemination in different ICUs and wards. This finding enhances the necessity of better observance of infection control practices, to prevent further dissemination of this challenging pathogen.

References

Slama TG: Gram-negative antibiotic resistance: there is a price to pay. Crit Care. 2008, 12 (4): 1-7. 10.1186/cc6817.

Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND: Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009, 22 (4): 582-610. 10.1128/CMR.00040-09.

Mesaros N, Nordmann P, Plésiat P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Van Eldere J, Glupczynski Y, Van Laethem Y, Jacobs F, Lebecque P, Malfroot A, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007, 13 (6): 560-578. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01681.x.

Nordmann P, Naas T, Fortineau N, Poirel L: Superbugs in the coming new decade; multidrug resistance and prospects for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 2010. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007, 10 (5): 436-440. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.07.004.

Strateva T, Yordanov D: Pseudomonas aeruginosa – a phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2009, 58 (9): 1133-1148. 10.1099/jmm.0.009142-0.

Tam VH, Rogers CA, Chang KT, Weston JS, Caeiro JP, Garey KW: Impact of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia on patient outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (9): 3717-3722. 10.1128/AAC.00207-10.

Glupczynski Y, Bogaerts P, Deplano A, Berhin C, Huang TD, Van Eldere J, Rodriguez-Villalobos H: Detection and characterization of class A extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Belgian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65 (5): 866-871. 10.1093/jac/dkq048.

Lin SP, Liu MF, Lin CF, Shi ZY: Phenotypic detection and polymerase chain reaction screening of extended-spectrum β-lactamases produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012, 45 (3): 200-207. 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.11.015. [Epub ahead of print]

Bush K: New beta-lactamases in gram-negative bacteria: diversity and impact on the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001, 32 (7): 1085-1089. 10.1086/319610.

Zhao WH, Hu ZQ: Beta-lactamases identified in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010, 36 (3): 245-258. 10.3109/1040841X.2010.481763.

Shu JC, Chia JH, Siu LK, Kuo AJ, Huang SH, Su LH, Wu TL: Interplay between mutational and horizontally acquired resistance mechanisms and its association with carbapenem resistance amongst extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (XDR-PA). Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012, 39 (3): 217-222. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.023.

Weldhagen GF, Poirel L, Nordmann P: Ambler class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel developments and clinical impact. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003, 47 (8): 2385-2392. 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2385-2392.2003.

Poirel L, Docquier JD, De Luca F, Verlinde A, Ide L, Rossolini GM, Nordmann P: BEL-2, an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase with increased activity toward expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (1): 533-535. 10.1128/AAC.00859-09.

Tian GB, Adams-Haduch JM, Bogdanovich T, Wang HN, Doi Y: PME-1, an extended-spectrum β-lactamase identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55 (6): 2710-2713. 10.1128/AAC.01660-10.

Picão RC, Poirel L, Gales AC, Nordmann P: Diversity of beta-lactamases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates causing bloodstream infections in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 53 (9): 3908-3913. 10.1128/AAC.00453-09.

Zhao WH, Chen G, Ito R, Hu ZQ: Relevance of resistance levels to carbapenems and integron-borne blaIMP-1, blaIMP-7, blaIMP-10 and blaVIM-2 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2009, 58 (8): 1080-1085. 10.1099/jmm.0.010017-0.

Picão RC, Andrade SS, Nicoletti AG, Campana EH, Moraes GC, Mendes RE, Gales AC: Metallo-β-Lactamase Detection: Comparative Evaluation of Double-Disk Synergy versus Combined Disk Tests for IMP-, GIM-, SIM- SPM-, or VIM-Producing Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46 (6): 2028-2037. 10.1128/JCM.00818-07.

Tenover FC: Potential impact of rapid diagnostic tests on improiving antimicrobial uses. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010, 1213: 70-80. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05827.x. [Epub ahead of print]

Endimiani A, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Kurz S, Jacobs MR, Perlin DS, Bonomo RA: Are we ready for novel detection methods to treat respiratory pathogens in hospital-acquired pneumonia?. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (S4): S373-S383.

,: Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 19th informational supplement, M100-S19. 2009, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

Tollentino FM, Polotto M, Nogueira ML, Lincopan N, Neves P, Mamizuka EM, Remeli GA, De Almeida MT, Rúbio FG, Nogueira MC: High Prevalence of blaCTX-M Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from a Tertiary Care Hospital: First report of blaSHV-12, blaSHV-31, blaSHV-38, and blaCTX-M-15 in Brazil. Microb Drug Resist. 2011, 17 (1): 7-16. 10.1089/mdr.2010.0055.

Yan JJ, Hsueh P, Ko W, Luh W, Tsai S, Wu HM, Wu JJ: Metallo-β-lactamases in clinical Pseudomonas isolates in Taiwan and identification of VIM-3, a novel variant of the VIM-2 enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45 (8): 2224-2228. 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2224-2228.2001.

Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, Alberti S, Bush K, Tenover FC: Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45 (4): 1151-1161. 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001.

Poirel L, Naas T, Delphine N, Collet L, Bellais S, Cavallo JD, Nordmann P: Characterization of VIM-2, a Carbapenem-Hydrolyzing Metallo-β-Lactamase and Its Plasmid- and Integron-Born Gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolate in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000, 44 (4): 891-897. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.891-897.2000.

Pitout JD, Gregson DB, Poirel L, McClure JA, Le P, Church DL: Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing metallo-beta-lactamases in a large centralized laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43 (7): 3129-3135. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3129-3135.2005.

Sambrook J, Russel DW: Purification of PCR products in preparation for cloning. In Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. 2001, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 8.25-8.26. 3

Silbert S, Pfaller MA, Hollis RJ, Barth AL, Sader HS: Evaluation of three molecular typing techniques for nonfermentative Gram-negative bacilli. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004, 25 (10): 847-851. 10.1086/502307.

Tsutsui A, Suzuki S, Yamane K, Matsui M, Konda T, Marui E, Takahashi K, Arakawa Y: Genotypes and infection sites in an outbreak of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Hosp Infect. 2011, 78 (4): 317-322. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.04.013.

Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B: Interpreting Chromosomal DNA Restriction Patterns Produced By Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis: Criteria For Bacterial Strain Typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33 (9): 2233-2239.

Lagatolla C, Tonin EA, Monti-Bragadin C, Dolzani L, Gombac F, Bearzi C, Edalucci E, Gionechetti F, Rossolini GM: Endemic carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with acquired metallo-beta-lactamase determinants in European hospital. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004, 10 (3): 535-538. 10.3201/eid1003.020799.

Paterson DL, Bonomo RA: Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005, 18 (4): 657-686. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005.

Maltezou HC: Metallo-β-Lactamase in Gram-negative bacteria: introducing the era of pan-resistence?. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008, 33 (5): 405-407.

Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR: Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007, 57 (1): 7-13. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.05.009.

van der Heijden IM, Levin AS, De Pedri EH, Fung L, Rossi F, Duboc G, Barone AA, Costa SF: Comparison of disc diffusion, Etest and broth microdilution for testing susceptibility of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa to polymyxins. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2007, 6: 8-10.1186/1476-0711-6-8.

Marra AR, Pereira CA, Gales AC, Menezes LC, Cal RG, De Souza JM, Edmond MB, Faro C, Wey SB: Bloodstream infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: epidemiology, microbiology and clinical outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006, 50 (1): 388-390. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.388-390.2006.

Franco MR, Caiaffa-Filho HH, Burattini MN, Rossi F: Metallo-beta-lactamases among imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Brazilian university hospital. Clinics. 2010, 65 (9): 825-829. 10.1590/S1807-59322010000900002.

Cornaglia G, Giamarellou H, Rossolini GM: Metallo-β-lactamases: a last frontier for β-lactams?. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11 (5): 381-393. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70056-1.

Gales AC, Menezes LC, Silbert S, Sader HS: Dissemination in distinct Brazilian regions of an epidemic carbapanem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing SPM metallo-β-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52 (4): 699-702. 10.1093/jac/dkg416.

Sader HS, Reis AO, Silbert S, Gales AC: IMPs, VIMs and SPMs: the diversity of metallo-beta-lactamases produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005, 11 (1): 73-76. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01031.x.

Martins AF, Zavascki AP, Gaspareto PB, Barth AL: Dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing SPM-1-like and IMP-1-like metallo-beta-lactamases in hospitals from southern Brazil. Infection. 2007, 35 (6): 457-460. 10.1007/s15010-007-6289-3.

Poirel L, Magalhaes M, Lopes M, Nordmann P: Molecular analysis of metallo-ß-lactamase gene blaSPM-1 surrounding sequences from disseminated Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Recife, Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004, 48 (4): 1406-1409. 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1406-1409.2004.

Salabi AE, Toleman MA, Weeks J, Bruderer T, Frei R, Walsh TR: First report of the metallo-beta-lactamase SPM-1 in Europe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (1): 582-10.1128/AAC.00719-09.

Silva FM, Carmo MS, Silbert S, Gales AC: SPM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: analysis of the ancestor relationship using multilocus sequence typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and automated ribotyping. Microb Drug Resist. 2011, 17 (2): 215-220. 10.1089/mdr.2010.0140.

Livermore DM: Multiple Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Our Worst Nightmare. Clin Infect Dis. 2002, 34 (5): 634-640. 10.1086/338782.

Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Poirel L, Nordmann P: Metallo-β-Lactamases: the Quiet before the Storm. Clin Microb Rev. 2005, 18 (2): 306-325. 10.1128/CMR.18.2.306-325.2005.

Walsh TR: Emerging carbapenemases: a global perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 36 (3): 8-14.

Docquier JD, Luzzaro F, Amicosante G, Toniolo A, Rossolini GM: Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing PER-1 extended-spectrum serine-beta-lactamase and VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001, 7 (5): 910-911.

Woodford N, Zhang J, Kaufmann ME, Yarde S, Tomas Mdel M, Faris C, Vardhan MS, Dawson S, Cotterill SL, Livermore DM: Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates producing VEB-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008, 62 (6): 1265-1268. 10.1093/jac/dkn400.

Mansour W, Dahmen S, Poirel L, Charfi K, Bettaieb D, Boujaafar N, Bouallegue O: Emergence of SHV-2a extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a university hospital in Tunisia. Microb Drug Resist. 2009, 15 (4): 295-301. 10.1089/mdr.2009.0012.

Naas T, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, Lartigue MF, Quinn JP, Nordmann P: Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the beta-lactamase blaKPC gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52 (4): 1257-1263. 10.1128/AAC.01451-07.

Picão RC, Poirel L, Gales AC, Nordmann P: Further identification of CTX-M-2 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 53 (5): 2225-2226. 10.1128/AAC.01602-08.

Labuschagne Cde J, Weldhagen GF, Ehlers MM, Dove MG: Emergence of class 1 integron-associated GES-5 and GES-5-like extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in South Africa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008, 31 (6): 527-530. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.020.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/176/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a FAPESP grant to MCLN. MLN is supported by FAPESP and CNPq Grants. MLN is recipient of a CNPq Fellowship. MP is a recipient of a CAPES Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

MP, TC and MCLN carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment. MGL, FGR, MTGA, MLN and MCLN participated in the design of the study. MGL, MTGA and MP collected and characterize the isolates. MLN, MTGA, MCLN and FGR analyzed the results. MP, MLN and MCLN drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Polotto, M., Casella, T., de Lucca Oliveira, M.G. et al. Detection of P. aeruginosa harboring bla CTX-M-2, bla GES-1 and bla GES-5, bla IMP-1 and bla SPM-1causing infections in Brazilian tertiary-care hospital. BMC Infect Dis 12, 176 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-176

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-176