Abstract

Background

This study conducted in Northeastern Brazil, evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori infection and the presence of gastritis in HIV-infected patients.

Methods

There were included 113 HIV-positive and 141 age-matched HIV-negative patients, who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms. H. pylori status was evaluated by urease test and histology.

Results

The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly lower (p < 0.001) in HIV-infected (37.2%) than in uninfected (75.2%) patients. There were no significant differences between H. pylori status and gender, age, HIV viral load, antiretroviral therapy and the use of antibiotics. A lower prevalence of H. pylori was observed among patients with T CD4 cell count below 200/mm3; however, it was not significant. Chronic active antral gastritis was observed in 87.6% of the HIV-infected patients and in 780.4% of the control group (p = 0.11). H. pylori infection was significantly associated with chronic active gastritis in the antrum in both groups, but it was not associated with corpus chronic active gastritis in the HIV-infected patients.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that the prevalence of H. pylori was significantly lower in HIV-positive patients compared with HIV-negative ones. However, corpus gastritis was frequently observed in the HIV-positive patients, pointing to different mechanisms than H. pylori infection in the genesis of the lesion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Helicobacter pylori infection is the major etiologic factor of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer in the general population. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are frequent among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [1, 2] However, the role of H. pylori infection in the GI tract mucosa of HIV patients is not well defined [3]. Some studies suggested that interactions between the immune/inflammatory response, gastric physiology and host repair mechanisms play an important role in dictating the disease outcome in response to H. pylori infection, suggesting that the host's immune competence might be an important issue in H. pylori infection [4, 5].

Data in regard to the prevalence of H. pylori infection in HIV-infected population are controversial. Some reports have shown that the rate of the infection in HIV-positive patients is remarkably low when compared with the general population [6, 7]. Conversely, other studies have not found similar results [8–10].

It is well known that the immune deficiencies caused by HIV give rise to many different gastrointestinal opportunistic infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and fungal esophagitis [11, 12]. However, there are few studies evaluating the gastric mucosa of patients co-infected by H. pylori and HIV [13–15].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of H. pylori infection, risk factors associated with the infection, as well as the macroscopic and microscopic alterations of the gastric mucosa of HIV-infected patients in a high H. pylori prevalence area in Northeastern, Brazil.

Methods

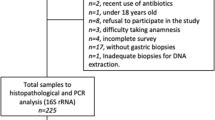

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Research of the University of Ceará, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. This prospective cross-sectional study was carried out at the Hospital São José, a major referral center for assistance of HIV-infected individuals in the city of Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. From May 2001 to April 2003, 113 HIV-positive patients who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms were included in the study. The control group was composed by 141 HIV-negative patients who were undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for investigation of dyspeptic symptoms at the University Hospital Walter Cantideo, Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil. Patients and age matched controls (interval of 10 years) were enrolled at the same period. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study and answered a questionnaire about symptoms and consumption of medications, including acid secretion inhibitors and antibiotics six months before endoscopy. In the HIV-positive patient group, data regarding the risk factors for HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy were also obtained. Total T CD4 cell count and HIV viral load were accepted as valid if the blood sample for their determination had been taken within 1 month before or after the entrance in the study.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Gastro-endoscopy was performed with Olympus video endoscopes (Olympus Optical Co, Ltd. GIF TYPE V) in the standard manner. Fragments of the gastric mucosa were obtained from the five sites recommended by the Houston-updated Sydney system for classification of gastritis and to evaluate the presence of spiral microorganism stained by Giemsa [16]. Two fragments from the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum and two from the lesser curvature of the lower gastric body were obtained for urease test. The activity of chronic gastritis was classified as mild, moderate and marked based on the number of neutrophil infiltration. The specimens were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and 5-mm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histology and with Giemsa staining to evaluate H. pylori status.

Exclusion criteria included age below 18 years old or above 80 years old, other serious medical problems, or previous treatment for H. pylori infection. H. pylori status was determined by the rapid urease test and histology (Giemsa staining) and was considered negative when both tests were negative.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the software SPSS (version 10.0, Chicago, IL). Chi square test with Yates' correction or Fischer's exact test were used to compare results among the different groups. Significance was accepted at P values below 0.05.

Results

Two hundred and fifty four subjects were included: 113 HIV-infected patients and 141 age-matched controls. The mean age of HIV infected patients was 36.0 years (range, 21-70 years) and 61.9% (70/113) were male. The mean age of the control group was 39.7 years (range 18-76 years) and 36.2% (51/141) were male. Most of the symptoms of HIV-positive patients were nonspecific, such as diarrhea, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, odynophagia or dysphagia. The frequency of diarrhea, odynophagia, and dysphagia was significantly higher in HIV-positive group compared with the controls (P < 0.05).

Macroscopic lesions in the HIV-infected group included, widespread esophageal candidiasis (32.7%; 37/113), esophageal ulcers (7.9%; 9/113) and candidiasis plus esophageal ulcers (1.7%; 2/113). Cryptosporidium was found in the gastric mucosa of two HIV-infected patients. Table 1 shows the endoscopic gastric mucosal findings in HIV-positive and HIV-negative dyspeptic patients. Corpus gastritis was significantly more frequently observed in the dyspeptic HIV-positive than in HIV-negative patients.

The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly lower (p < 0.001) in HIV-infected patients (37.2%; 42/113) when compared with the controls (75.2%; 106/141); and did not increase with age (p = 0.73). Of note, the infection prevalence in the oldest group did not differ between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the HIV-positive patients and controls according to the age is shown in Figure 1.

In the HIV-positive group, there was no significant difference between H. pylori status and gender, age, HIV viral load, antiretroviral therapy and the use of antibiotics and H2-blocker. Only 4 patients referred the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI). A non-significant lower prevalence of H. pylori infection was observed in the patients with T CD4 cell count below 200 (Table 2).

The gastric mucosa histological results are shown in Table 3. Chronic active antral gastritis was observed in 87.6% (99/113) of the HIV-infected patients and in 80.1% (113/141; p = 0.11) of the control group. H. pylori infection was significantly associated with the presence of chronic active antral gastritis in both groups (p = 0.03 and p < 0.001, respectively). No significant difference (p = 0.89) was also observed between the groups in respect to the frequency of chronic active corpus gastritis (53.1% in the HIV-positive patients and 53.9% in the HIV-negative patient). However, the H. pylori infection did not associate with chronic active corpus gastritis in the HIV-positive patients (p = 0.15), but high association was observed in the HIV-negative ones (p < 0.001). Additionally, in the HIV-negative group, the degree of gastritis was also associated with H. pylori infection, being the presence of the microorganism more frequently observed in the more marked (50%, 40/80) than in moderated (10%, 2/20) gastritis. Atrophy/intestinal metaplasia was observed less frequently in the gastric corpus of HIV-positive (6.2%, 7/113) than in the gastric corpus of HIV-negative (9.9%, 14/141) patients, but the differences were not significant (p = 0.27).

Discussion

The prevalence of H. pylori infection was lower in the HIV-positive group than in the age-matched controls. The low prevalence of H. pylori infection we observed in the HIV-positive patients differs profoundly from that previously reported (82.0%) in HIV-negative adults from a poor urban Community in the same city (Fortaleza; Brazil) [17]. A similar result has been observed in a cross-sectional study in Southeastern Brazil that evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori infection in 528 HIV-infected patients (32.38% of H. pylori positivity) [18]. Studies from East countries, where H. pylori infection is highly prevalent such as Taiwan [19] and China [20] also demonstrated a lower H. pylori infection prevalence (17.3% and 22.1%, respectively) in HIV-infected than in-non-infected (63.5% and 44.8%, respectively) patients. Conversely, studies from Argentina and from India showed similar H. pylori infection prevalence in HIV-infected and non infected patients [13, 21, 22].

It has to be emphasized that H. pylori infection was diagnosed by histology and urease test in all patients. The results were concordant with those obtained by the evaluation of H. pylori specific ureA gene in the paraffin imbedded gastric tissue from a subgroup of patients (data not shown) and both HIV-positive and -negative patients belong to the same low-income population. As above mentioned, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in a similar population from Fortaleza in respect to the socio-economical level is high [17]. It is well known that H. pylori infection is mainly acquired during childhood and that once acquired it is life-long lasting [1]. Therefore, we may hypothesize that the HIV-infected patients we studied had been exposed to the bacterium early in life and most of them became infected, but loose the infection after acquired HIV infection. Alternatively, the H. pylori gastric load might be decreased in the HIV-positive patients leading to H. pylori infection misdiagnosis. Explanations include decreased gastric acid secretion predisposing to gastric colonization by other microorganisms that might compete with H. pylori, the use of either antibiotics or PPI and, as suggested in other studies, the low count of T CD4 cells in AIDS patients [6, 21, 23, 24].

It has been suggested that T CD4 cells play a role in inducing or perpetuating tissue and epithelial damage that may facilitate H. pylori colonization [25]. In this study, HIV-positive patients were stratified according to the T CD4 cell counts above or below 200 cells/mm3 and a tendency of lower prevalence of H. pylori infection was observed in the group of patients with T CD4 cell count of 200 or below.

Hypochlorhydria has been described in HIV-positive patients [23]. Previous studies have shown that HIV-positive patients with overt AIDS have significantly increased serum levels of gastrin and pepsinogen II compared with HIV-positive patients without overt AIDS [26]. Hypochlorhydria may provide a less suitable environment for H. pylori and predispose to overgrowth of other bacteria [27]. Inhibition of H. pylori by competition with other opportunistic pathogens such as Cytomegalovirus via unknown mechanisms has been also suggested [23, 28]. The intragastric environment may be also modified by previous use of PPI. In this study; however, only four HIV-positive patients were under PPI therapy. The frequent usage of antibiotics for treatment or prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in patients at an advanced stage of HIV infection might explain the low prevalence of H. pylori infection in the patient group. However, the antibiotics most commonly used in AIDS patients are not always efficacious against H. pylori. Furthermore, low H. pylori eradication ratio is observed with the use of mono therapy, even with clarithromycin that has a good anti-H. pylori activity [29].

An interesting finding observed in this study was the presence of active chronic gastritis in the gastric body of HIV-positive patients independently of the H. pylori positivity, in agreement with the studies of Welage et al.; Marano et al., and Mach et al. [23, 30, 31], which; however, was not observed by others [6, 32]. Otherwise, in this study, the H. pylori status was significantly associated with the presence of active chronic gastritis in the antral gastric mucosa of HIV-positive and -negative patients. Taking together the data, it is possible that different mechanisms participate in the development of corpus chronic active gastritis in HIV-positive patients. Therefore, other microorganisms such as Cytomegalovirus or some drugs used to treat AIDS and to prevent opportunistic infections may play a role [18, 33].

Conclusion

Although the prevalence of H. pylori infection in HIV-positive patients was lower than in HIV-negative ones, the presence of chronic active gastritis was similarly high either in HIV-positive or -negative patients, which points to the possibility that other mechanisms than H. pylori infection are involved in the genesis of corpus gastritis in HIV positive patients.

References

Peterson WL: Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324: 1043-1048. 10.1056/NEJM199106273242623.

Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL: Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321: 1562-1566. 10.1056/NEJM198912073212302.

Romanelli F, Smith KM, Murphy BS: Does HIV infection alter the incidence or pathology of Helicobacter pylori infection?. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007, 21 (12): 908-919. 10.1089/apc.2006.0215.

Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe S: Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998, 114: 482-492. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70531-1.

Moran AP, Svennerholm AM, Penn CW: Pathogenesis and host response of Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 2002, 10 (12): 545-7. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02481-2.

Edwards PD, Carrick J, Turner J, Lee A, Mitchell H, Cooper DA: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis is rare in AIDS: antibiotic effect or a consequence of immunodeficiency?. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991, 86: 1761-1764.

Francis ND, Logan RP, Walker MM, Polson RJ, Boylston AW, Pinching AJ, Harris JR, Baron JH: Campylobacter pylori in the upper GI tract of the patients with HIV-1 infection. J Clin Pathol. 1990, 43: 60-2. 10.1136/jcp.43.1.60.

Sud A, Ray P, Bhasin D, Wanchu A, Bambery P, Singh S: Helicobacter pylori in Indian HIV infected patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002, 23 (2): 79-81.

Olmos M, Araya V, Pskorz E, Quesada EC, Concetti H, Perez H, Cahn P: Coinfection: Helicobacter pylori/human immunodeficiency virus. Dig Dis Sci. 2004, 49: 1836-39. 10.1007/s10620-004-9580-5.

Alimohamed F, Lule GN, Nyong'o A, Bwayo J, Rana FS: Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and endoscopic findings in HIV seropositive patients with upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms at Kenyatta national hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2002, 79: 226-231.

Francis ND, Boylston AW, Roberts AH, Parkin JM, Pinching AJ: Cytomegalovirus infection in gastrointestinal tracts of patients infected with HIV-1 or AIDS. J Clin Pathol. 1989, 42: 1055-1064. 10.1136/jcp.42.10.1055.

Dieterich DT, Wilcox CM: Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal diseases associated with HIV infection. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996, 91: 2265-2269.

Sud A, Ray P, Bhasin D, Wanchu A, Bambery P, Singh S: Helicobacter pylori in Indian HIV infected patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002, 23 (2): 79-81.

Battan R, Raviglione MC, Palagiano A, Boyle JF, Sabatini MT, Sayad K, Ottaviano LJ: Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990, 85: 1576-1579.

Lim SG, Lipman MC, Squire S, Pillay D, Gillespie S, Sankey EA, Dhillon AP, Johnson MA, Lee CA, Pounder RE: Audit of endoscopic surveillance biopsy specimens in HIV positive patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 1993, 34 (10): 1429-32. 10.1136/gut.34.10.1429.

Dixon MF, Path FRC, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P: Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International workshop on the histopathology of gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996, 20: 1161-81. 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001.

Rodrigues MN, Queiroz DM, Rodrigues RT, Rocha AM, Braga Neto MB, Braga LL: Helicobacter pylori infection in adults from a poor urban community in northeastern Brazil: demographic, lifestyle and environmental factors. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005, 9 (5): 405-10. 10.1590/S1413-86702005000500008.

Werneck-Silva AL, Prado IB: Dyspepsia in HIV-infected patients under highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, 22 (11): 1712-1716. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04897.x.

Chiu HM, Wu MS, Hung CC, Shun CT, Lin JT: Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori but high prevalence of cytomegalovirus associated peptic ulcer disease in AIDS patients: Comparative study of symptomatic subjects evaluated by endoscopy and CD4 counts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004, 19 (4): 423-428. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03278.x.

Fu-Jing LV, Xiao-Lan Luo, Meng Xin, Rui Jin, Ding Hui-Guo, Shu-Tian Zhang: A low prevalence of H pylori and endoscopic findings in HIVpositive Chinese patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13 (41): 5492-5496.

Olmos M, Araya V, Pskorz E, Quesada EC, Concetti H, Perez H, Cahn P: Coinfection: Helicobacter pylori/human immunodeficiency virus. Dig Dis Sci. 2004, 49: 1836-39. 10.1007/s10620-004-9580-5.

Alimohamed F, Lule GN, Nyong'o A, Bwayo J, Rana FS: Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and endoscopic findings in HIV seropositive patients with upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms at Kenyatta national hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2002, 79: 226-231.

Welage LS, Carver PL, Revankar S, Pierson C, Kauffman CA: Alterations in gastric acidity in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1995, 21: 1431-8.

Lichterfeld M, Lorenz C, Nischalke HD, Scheurlen C, Sauerbruch T, Rockstroh JK: Decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in HIV patients with AIDS defining diseases. Z Gastroenterol. 2002, 40: 11-4. 10.1055/s-2002-19637.

Bontems P, Fabienne R, Van Gossum A, Cadranel S, Mascart F: Helicobacter pylori modulation of gastric and duodenal mucosal T cell cytokine secretions in children compared with adults. Helicobacter. 2003, 8 (3): 216-226. 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00147.x.

Fabris P, Pilotto A, Bozzola L, Tositti G, Soffiatis G, Manfrin V: Serum pepsinogen and gastrin levels in HIV-positive patients: relationship with CD4+ cell count and Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002, 16: 807-11. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01234.x.

Lake-Bakaar G, Quadros E, Beidas S, Elsakr M, Tom W, Wilson DE, Dincsoy HP, Cohen P, Straus EW: Gastric secretory failure in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1988, 109: 502-4.

Shaffer RT, LaHatte LJ, Kelly JW, Kadakia S, Carrougher JG, Keate RF, Starnes EC: Gastric acid secretion in HIV-1 infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992, 12: 1777-80.

Peterson WL, Graham DY, Marshall B, Blaser MJ, Genta RM, Klein PD, Stratton CW, Drnec J, Prokocimer P, Siepman N: Clarithromycin as monotherapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993, 88: 1860-4.

Marano B, Smith F, Bonanno C: Helicobacter pylori prevalence in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993, 88 (5): 687-690.

Mach T, Skwara P, Biesiada G, Cieśla A, Macura : Morphological changes of the upper gastrointestinal tract mucosa and Helicobacter pylori infection in HIV-positive patients with severe immunodeficiency and symptoms of dyspepsia. Med Sci Monit. 2007, 13 (1): 14-19.

Skwara P, Mach T, Tomaszewska R: Morphological changes of gastric mucosa in HIV-infected patients. HIV&AIDS Review. 2002, 2: 47-51.

Rossi P, Rivasi F, Codeluppi M, Catania A, Tamburrini A, Righi E, Pozio E: Gastric involvement in AIDS associated cryptosporidiosis. Gut. 1998, 43: 476-77. 10.1136/gut.43.4.476.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/11/13/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EG: participated in the conception, performed the endoscopies, and helped writing the manuscript. MB and ABN participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation and critical writing of the manuscript. AMN: participated in implementation of the study, data collection, database management and statistical analysis. CT and CS: participated in design and implementation of the study. KC, JS and IS: participated in implementation of the study, data collection IM: statistical analysis, interpretation and writing the manuscript. DQ: performed critical writing and reviewing LB: participated in conception, design, implementation, coordination of the study and critical writing and reviewing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fialho, A.B., Braga-Neto, M.B., Guerra, E.J. et al. Low prevalence of H. pylori Infection in HIV-Positive Patients in the Northeast of Brazil. BMC Gastroenterol 11, 13 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-11-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-11-13