Abstract

Background

Peak first derivative of femoral artery pressure (arterial dP/dtmax) derived from fluid-filled catheter remains questionable to assess left ventricular (LV) contractility during shock. The aim of this study was to test if arterial dP/dtmax is reliable for assessing LV contractility during various hemodynamic conditions such as endotoxin-induced shock and catecholamine infusion.

Methods

Ventricular pressure-volume data obtained with a conductance catheter and invasive arterial pressure obtained with a fluid-filled catheter were continuously recorded in 6 anaesthetized and mechanically ventilated pigs. After a stabilization period, endotoxin was infused to induce shock. Catecholamines were transiently administrated during shock. Arterial dP/dtmax was compared to end-systolic elastance (Ees), the gold standard method for assessing LV contractility.

Results

Endotoxin-induced shock and catecholamine infusion lead to significant variations in LV contractility. Overall, significant correlation (r = 0.51; p < 0.001) but low agreement between the two methods were observed. However, a far better correlation with a good agreement were observed when positive-pressure ventilation induced an arterial pulse pressure variation (PPV) ≤ 11% (r = 0.77; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

While arterial dP/dtmax and Ees were significantly correlated during various hemodynamic conditions, arterial dP/dtmax was more accurate for assessing LV contractility when adequate vascular filling, defined as PPV ≤ 11%, was achieved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction occurs more frequently than expected while its severity is often underestimated [1]. Indeed, quantification of left ventricular (LV) inotropic function during sepsis is an ongoing preoccupation of clinicians. The theoretical gold standard for assessment of LV contractility is the end-systolic pressure volume relation (ESPVR). The slope of the relation defines the maximum elastance, also called end-systolic elastance (Ees), a load-independent index of LV contractility [2]. However, this method is difficult to apply in clinical practice because requiring preload reduction and catheterization of the left ventricle with a high-fidelity pressure catheter. Several other contractility indices have been proposed but most of them are influenced by cardiac loading conditions [3–8]. A relative exception to this is the peak first derivative of LV pressure (LV dP/dtmax) which is relatively afterload independent [9]. Most critically ill patients with hemodynamic instability are instrumented with a femoral fluid-filled catheter for accurate arterial pressure monitoring. dP/dtmax can be derived from the arterial pressure curve (the maximal ascending slope of the peripheral arterial pressure curve). However, the use of arterial dP/dtmax as an index of LV contractility remains questionable because dP/dtmax is derived from arterial pressure obtained with a fluid-filled catheter and is influenced by preload and vascular filling conditions [4, 10]. Vascular filling and fluid requirement in critically ill patients are usually assessed by positive-pressure ventilation-induced arterial pulse pressure variation (PPV), which is a sensitive and specific predictor of preload responsiveness. PPV is measured over a single respiratory cycle and defined as the maximal pulse pressure (systolic-diastolic pressure) less the minimal pulse pressure divided by the average of these two pressures. In hypovolemic states, PPV due to cycling pressure gradient from mechanical ventilation is high. However, when adequate vascular filling is obtained, PPV is low [11]. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether arterial dP/dtmax derived from fluid-filled femoral artery catheter can be used to assess LV contractility in different hemodynamic conditions. To test this hypothesis, arterial dP/dtmax, LV dP/dtmax and Ees were compared during various alterations in LV contractile function resulting from endotoxin-induced shock and catecholamine infusion. PPV was continuously monitored to assess the vascular filling.

Methods

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Liege and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Experimental model

Experiments were performed on 6 healthy pure Pietran pigs of either sex weighing from 16 to 28 kg. The animals were premedicated with intramuscular administration of tiletamine (250 mg) and zolazepam (250 mg). Anaesthesia was then induced and maintained by a continuous infusion of sufentanil (0.5 μg/kg/h) and pentobarbital (5 mg/kg/h). Spontaneous movements were prevented by cisatracurium (0.1 mg/kg/h). After endotracheal intubation via a cervical tracheostomy, the pigs were connected to a volume-cycled ventilator (Datex Ohmeda, Engström Carestation, General Electric, USA) set to deliver a tidal volume of 10 ml/kg at a respiratory rate of 20/min with a FiO2 of 0.4 and a PEEP of 5 cm H2O. A 7F, multi-electrode (9-mm interelectrode distance) conductance micromanometer-tipped catheter (Scisense, Canada) was inserted through the left carotid artery into the left ventricle and positioned so that all electrodes remained in the LV cavity. A central venous line was inserted into the right jugular vein and placed inside the superior vena cava. Arterial blood pressure was monitored via a 4F fluid-filled catheter (Pulsiocath, Pulsion Medical System, Germany) inserted into the right femoral artery. A 6F Fogarty balloon catheter (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Oakland, CA, USA) was advanced into the inferior vena cava through a right femoral venotomy. Inflation of this balloon produced a gradual preload reduction.

Experimental protocol

After surgical preparation, the animals were allowed to stabilize for 30 min ('basal' period). Hemodynamic data including mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate (HR), cardiac output (CO), LV volume and pressure, were continuously recorded. Then, the animals had a 0.5 mg/kg intravenous infusion of a freshly prepared endotoxin solution (lipopolysaccharide from E.coli serotype 0127:B8, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) over 30 min ('endo' period). When systolic arterial pressure significantly dropped, dobutamine (5 mcg/kg/min) and norepinephrine (0.05 mcg/kg/min) were administrated during 60 minutes ('catechol' period) and then stopped ('shock' period). Fluid administration with Hartmann's solution was continuously controlled by preload responsiveness. When PPV was ≤ 11%, animals were considered as adequately filled.

Data collection and analysis

All analog signals were continuously digitalized and recorded (Notocord-hem evolution, Notocord, Paris, France). During each period of measurement, three transient occlusions of the inferior vena cava using the Fogarty balloon were performed during apnea. Analysis of the signals was performed offline. Arterial dP/dtmax and LV_dP/dtmax were calculated on 6 steady-state cycles just before occlusion of the vena cava. These indices were compared with the gold-standard Ees, calculated during transient preload reduction.

Statistical analysis

Arterial dP/dtmax, LV dP/dtmax and Ees were compared using linear regressions. A normalized Bland-Altman test (Statistica version 7, StatSoft) was also performed. Changes in hemodynamic parameters were evaluated by a repeated-measures analysis of variance. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

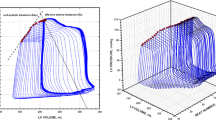

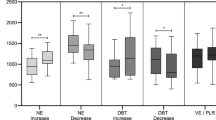

The effects of endotoxin infusion and catecholamine administration on arterial pressure, HR, ejection fraction (EF) and cardiac output (CO) are summarized in Table 1. The evolution of LV contractility assessed by both Ees and arterial dP/dtmax is shown in Figure 1. Ees significantly decreased from 1.63 ± 0.4 to 1.18 ± 0.55 mm Hg/mL during the state of shock. Arterial and LV dP/dtmax significantly decreased from 1004 ± 41 and 2414 ± 514 to 795 ± 305 and 1235 ± 224 mm Hg/sec, respectively. However, during catecholamine infusion, Ees significantly increased to 2.5 ± 0.77 mm Hg/mL and arterial and LV dP/dtmax significantly increased to 1872 ± 491 and 3181 ± 485 mm Hg/sec, respectively.

LV contractility assessed by both Ees and arterial dP/dt max . Basal conditions ('basal'), immediately after endotoxin infusion ('endo'), during shock with and without catecholamine infusion ('catechol' and 'shock' respectively). Values are given as mean ± SD. All directional changes in contractility were significant (p < 0.05) for each challenge, except between 'basal' and 'endo'.

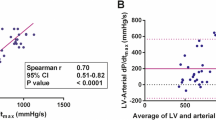

Overall, arterial dP/dtmax and Ees were significantly correlated (r = 0.51, p < 0.001) but there was low agreement (Figures 2 and 3). LV dP/dtmax and arterial dP/dtmax were significantly correlated (r = 0.58, p < 0.001) but arterial dP/dtmax systematically underestimated LV dP/dtmax. (bias = 1018 ± 364 mmHg/sec). LV dP/dtmax and Ees were significantly correlated (r = 0.78, p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Normalized Bland-Altman plot of the agreement between Ees and arterial dP/dt max . Average = (Ees° + arterial dP/dtmax°)/2 and difference = Ees° - arterial dP/dtmax° where X° is the normalized value of X [X° = (value of X - mean of X)/standard deviation of X]. Lines represent mean difference (solid lines) and 95% confidence interval (light dashed line) (PPV ≤ 11%).

When adequate filling (PPV ≤ 11%) was obtained, a far better correlation between arterial dP/dtmax and Ees was found (r = 0.77, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). In that case, normalized Bland-Altman analysis revealed a good agreement between the two methods (Figure 3). Correlation between LV dP/dtmax and arterial dP/dtmax was also improved when adequate filling was achieved (r = 0.66, p < 0.001) while correlation between LV dP/dtmax and Ees did not significantly changed (r = 0.76, p < 0.001) (Figure 5).

Discussion

Determination of LV contractility is a cornerstone in clinical practice [6, 12]. Numerous methods for assessing LV contractility have been reported but none have been adequately validated in clinical practice, or require the presence of an intraventricular pressure catheter, prohibiting routine use in clinical practice [13, 14]. The gold standard method, Ees, requires both ventricular pressure and volume measurements on a beat to beat basis with preload variation [2]. Single beat analysis has been developed, but requires the whole ventricular pressure waveform [15]. dP/dtmax can be easily calculated in clinical practice but is sensitive to both LV contractility and preload [9]. In the present study, we tested whether arterial dP/dtmax, derived from femoral fluid-filled catheter, was accurate for assessing LV contractility. While LV dP/dtmax is considered as a good index of LV contractility despite its preload dependence, little is known about arterial dP/dtmax [16, 17]. One study performed in perioperative patients found that arterial dP/dtmax and LV dP/dtmax were significantly correlated and concluded that changes in arterial dP/dtmax were accurate for assessing changes LV contractility [18]. To the best of our knowledge, despite its wide use in critically ill patients, arterial dP/dtmax has never been directly compared with Ees during changes in LV function, at different levels of vascular filling. Our results demonstrated that there was significant correlation between arterial dP/dtmax and Ees. Furthermore, a far better correlation with a good agreement between arterial dP/dtmax and Ees were observed when adequate vascular filling was achieved. Similar improvement was observed between arterial and LV dP/dtmax. However, correlation between LV dP/dtmax and Ees did not significantly change when adequate vascular filling was achieved. Arterial dP/dtmax is an ejection phase index depending on arterial compliance and waves reflections from periphery to aorta. All factors that may affect arterial compliance and waves reflections (vascular filling conditions, vasoactive agents) may also affect arterial dP/dtmax independently of LV contractile function. As a result, the combination of fluid responsiveness and changes in arterial compliance and waves reflections due to endotoxin and/or catecholamines could enhance discrepancies between arterial and LV dP/dtmax and consequently between arterial dP/dtmax and the reference method, Ees [19]. In this study, fluid administration was directed by PPV.

Adequate vascular filling was defined as PPV ≤ 11%. On the basis of clinical settings, this PPV threshold value allows the best discrimination between responders and nonresponders to intravascular fluid administration [20–23]. In perioperative patients, De Hert et al. showed that changes in femoral dP/dtmax accurately reflected changes in LV dP/dtmax during various interventions. However, absolute values of LV contractility are required for potential ventriculo-arterial interaction analysis [24]. These authors also found that leg elevation induced significant increase in central venous pressure and LV end-diastolic pressure, but arterial and LV dP/dtmax remained unaltered [18]. However, it is well recognized that static indices (like central venous pressure or LV end-diastolic pressure) are poor indicators of vascular filling and preload responsiveness [11]. Masutani et al. showed that LV dP/dtmax can be predicted from aortic dP/dtmax but their method requires aortic impedance which is difficult to calculate in clinical practice [25]. Therefore, assessing LV contractility from arterial dP/dtmax, when adequate vascular filling is achieved, could be a simple and accurate method with the potential for ventriculo-arterial interaction analysis.

Other methodological issues should be taken into account. First, the use of a fluid-filled catheter could be another source of discrepancy between arterial dP/dtmax and Ees. As pointed out by numerous authors, pressure waves measured with a fluid-filled catheter have to be interpreted cautiously, because the pressure waveform may be distorted by the dynamic response of the catheter. By taking care of a properly flushed catheter system and by filtering out artifacts, the catheter response were optimized in our study [26]. Secondly, arterial and LV dP/dtmax could also be influenced by heart rate. Heart rate variability was not significant enough to analyze its influence on arterial dP/dtmax in the present observations.

Conclusions

Arterial dP/dtmax, the minimally invasive method derived from femoral artery fluid-filled pressure catheter and Ees, the reference method for assessing LV contractility, derived from intraventricular conductance micromanometer-tipped catheter, were significantly correlated over a wide range of hemodynamic conditions resulting from endotoxin-induced shock and catecholamine infusion. However, arterial dP/dtmax was more accurate for assessing LV contractility when adequate vascular filling, defined as PPV ≤ 11%, was achieved. Using dynamic indices to ensure adequate vascular filling, LV contractility could be accurately predicted by arterial dP/dtmax derived from femoral artery fluid-filled pressure catheter in critically ill patients.

References

Levy RJ, Piel DA, Acton PD, Zhou R, Ferrari VA, Karp JS, Deutschman CS: Evidence of myocardial hibernation in the septic heart. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 2752-2756. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000189943.60945.77.

Sagawa K, Maughan WL, Suga H, Sunagawa K: Cardiac contraction and the pressure-volume relationship. 1988, New York & Oxford: Oxford Univ Press

Drake-Holland AJ, Mills CJ, Noble MI, Pugh S: Responses to changes in filling and contractility of indices of human left ventricular mechanical performance. J Physiol. 1990, 422: 29-39.

Kass DA, Maughan WL, Guo ZM, Kono A, Sunagawa K, Sagawa K: Comparative influence of load versus inotropic states on indexes of ventricular contractility: experimental and theoretical analysis based on pressure-volume relationships. Circulation. 1987, 76: 1422-1436. 10.1161/01.CIR.76.6.1422.

Lambert CR, Nichols WW, Pepine CJ: Indices of ventricular contractile state: comparative sensitivity and specificity. Am Heart J. 1983, 106: 136-144. 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90451-9.

Robotham JL, Takata M, Berman M, Harasawa Y: Ejection fraction revisited. Anesthesiology. 1991, 74: 172-183. 10.1097/00000542-199101000-00026.

Zhong L, Tan RS, Ghista DN, Ng EY, Chua LP, Kassab GS: Validation of a novel noninvasive cardiac index of left ventricular contractility in patients. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007, 292: H2764-H2772. 10.1152/ajpheart.00540.2006.

Quinones MA, Gaasch WH, Alexander JK: Influence of acute changes in preload, afterload, contractile state and heart rate on ejection and isovolumic indices of myocardial contractility in man. Circulation. 1976, 53: 293-302.

Little WC: The left ventricular dP/dtmax-end-diastolic volume relation in closed-chest dogs. Circ Res. 1985, 56: 808-815.

Gillebert TC, Leite-Moreira AF, De Hert SG: Relaxation-systolic pressure relation. A load-independent assessment of left ventricular contractility. Circulation. 1997, 95: 745-752.

Michard F, Teboul JL: Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest. 2002, 121: 2000-2008. 10.1378/chest.121.6.2000.

Schiller NB: Ejection fraction by echocardiography: the full monty or just a peep show?. Am Heart J. 2003, 146: 380-382. 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00247-3.

Bargiggia GS, Bertucci C, Recusani F, Raisaro A, de Servi S, Valdes-Cruz LM, Sahn DJ, Tronconi L: A new method for estimating left ventricular dP/dt by continuous wave Doppler-echocardiography. Validation studies at cardiac catheterization. Circulation. 1989, 80: 1287-1292. 10.1161/01.CIR.80.5.1287.

Bendjelid K, Romand JA: Fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a review of indices used in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2003, 29: 352-360.

Takeuchi M, Igarashi Y, Tomimoto S, Odake M, Hayashi T, Tsukamoto T, Hata K, Takaoka H, Fukuzaki H: Single-beat estimation of the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relation in the human left ventricle. Circulation. 1991, 83: 202-212.

Mason DT: Usefulness and limitations of the rate of rise of intraventricular pressure (dp-dt) in the evaluation of myocardial contractility in man. Am J Cardiol. 1969, 23: 516-527. 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90005-8.

Mason DT, Braunwald E, Covell JW, Sonnenblick EH, Ross J: Assessment of cardiac contractility. The relation between the rate of pressure rise and ventricular pressure during isovolumic systole. Circulation. 1971, 44: 47-58.

De Hert SG, Robert D, Cromheecke S, Michard F, Nijs J, Rodrigus IE: Evaluation of left ventricular function in anesthetized patients using femoral artery dP/dt(max). J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006, 20: 325-330. 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.11.006.

Perel A: Automated assessment of fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients. Anesth Analg. 2008, 106: 1031-1033. 10.1213/ane.0b013e318167abe5.

Kramer A, Zygun D, Hawes H, Easton P, Ferland A: Pulse pressure variation predicts fluid responsiveness following coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest. 2004, 126: 1563-1568. 10.1378/chest.126.5.1563.

Auler JO, Galas F, Hajjar L, Santos L, Carvalho T, Michard F: Online monitoring of pulse pressure variation to guide fluid therapy after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008, 106: 1201-1206. 10.1213/01.ane.0000287664.03547.c6. table.

Biais M, Stecken L, Ottolenghi L, Roullet S, Quinart A, Masson F, Sztark F: The ability of pulse pressure variations obtained with CNAP device to predict fluid responsiveness in the operating room. Anesth Analg. 2011, 113: 523-528.

Feissel M, Badie J, Merlani PG, Faller JP, Bendjelid K: Pre-ejection period variations predict the fluid responsiveness of septic ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33: 2534-2539. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000186415.43713.2F.

Kass DA, Kelly RP: Ventriculo-arterial coupling: concepts, assumptions, and applications. Ann Biomed Eng. 1992, 20: 41-62. 10.1007/BF02368505.

Masutani S, Iwamoto Y, Ishido H, Senzaki H: Relationship of maximum rate of pressure rise between aorta and left ventricle in pediatric patients. Implication for ventricular-vascular interaction with the potential for noninvasive determination of left ventricular contractility. Circ J. 2009, 73: 1698-1704. 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0954.

Lambermont B, Gerard P, Detry O, Kolh P, Potty P, D'Orio V, Marcelle R: Correction of pressure waveforms recorded by fluid-filled catheter recording systems: a new method using a transfer equation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998, 42: 717-720. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05307.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/12/13/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Leon Fredericq Foundation of the University of Liege.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

PM conceived the study, participated in the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. BL and TD participated in the experiments, analyzed the data and helped to draft the manuscript. NJ participated in the experiments. GC participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. VD participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Morimont, P., Lambermont, B., Desaive, T. et al. Arterial dP/dtmax accurately reflects left ventricular contractility during shock when adequate vascular filling is achieved. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 12, 13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-12-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-12-13