Abstract

Background

Cyclopropane fatty acids (CPA) have been found in certain gymnosperms, Malvales, Litchi and other Sapindales. The presence of their unique strained ring structures confers physical and chemical properties characteristic of unsaturated fatty acids with the oxidative stability displayed by saturated fatty acids making them of considerable industrial interest. While cyclopropenoid fatty acids (CPE) are well-known inhibitors of fatty acid desaturation in animals, CPE can also inhibit the stearoyl-CoA desaturase and interfere with the maturation and reproduction of some insect species suggesting that in addition to their traditional role as storage lipids, CPE can contribute to the protection of plants from herbivory.

Results

Three genes encoding cyclopropane synthase homologues GhCPS1, GhCPS2 and GhCPS3 were identified in cotton. Determination of gene transcript abundance revealed differences among the expression of GhCPS1, 2 and 3 showing high, intermediate and low levels, respectively, of transcripts in roots and stems; whereas GhCPS1 and 2 are both expressed at low levels in seeds. Analyses of fatty acid composition in different tissues indicate that the expression patterns of GhCPS1 and 2 correlate with cyclic fatty acid (CFA) distribution. Deletion of the N-terminal oxidase domain lowered GhCPS's ability to produce cyclopropane fatty acid by approximately 70%. GhCPS1 and 2, but not 3 resulted in the production of cyclopropane fatty acids upon heterologous expression in yeast, tobacco BY2 cell and Arabidopsis seed.

Conclusions

In cotton GhCPS1 and 2 gene expression correlates with the total CFA content in roots, stems and seeds. That GhCPS1 and 2 are expressed at a similar level in seed suggests both of them can be considered potential targets for gene silencing to reduce undesirable seed CPE accumulation. Because GhCPS1 is more active in yeast than the published Sterculia CPS and shows similar activity when expressed in model plant systems, it represents a strong candidate gene for CFA accumulation via heterologous expression in production plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fatty acids containing three-carbon carbocyclic rings, especially cyclopropane fatty acids, occur infrequently in plants and their major plant producers include Malvaceae, Sterculiaceae, Bombaceae, Tilaceae, Gnetaceae and Sapindaceae [1–4]. They can represent a significant component of seed oils and accumulate to as much as 40% in Litchi chinensis [1, 5].

Cyclopropane synthases (CPSs) catalyze the cyclopropanation of unsaturated lipids in bacteria [6, 7], plants [8, 9] and parasites [10]. There are two principle classes of bacterial cyclopropane synthases: the Escherichia coli cyclopropane synthase (ECPS) type that uses unsaturated phospholipids as substrates and Mycobacterium tuberculosis cyclopropane mycolic acid synthases (CMAs) that perform the introduction of cis-cyclopropane rings at proximal and distal positions of unsaturated mycolic acids [11–14]. Despite their different substrates the two classes of enzymes share up to 33% sequence identity suggesting a common fold and reaction mechanism. Moreover, a shared reaction mechanism is suggested by the fact that both E. coli CPS and M. tuberculosis CMA active site residues are almost completely conserved and harbor a bicarbonate ion in their active site [15, 16].

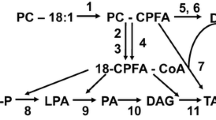

Although CPA had been identified in a few plant seeds as early as 1960s [17], the key gene responsible for their biochemical synthesis was not identified for more than three decades when Bao et al. [8] identified a cyclopropane synthase from S. foetida. The SfCPS is a microsomal-localized membrane enzyme, which catalyzes the addition of a methylene group derived from S-adenosyl-L-methionine across the double bond of oleic acid esterified to the sn-1 position of PC [9]. The S. foetida enzyme is the first plant CPS that has been characterized, the other plant CPS has been reported to date is from Litchi sinensis (WO/2006087364).

E. coli CPS is thought to be involved in the long-term survival of non-growing cells and its expression can be associated with environmental stresses [6]. Plant CPEs inhibit some insect stearoyl-CoA desaturases thereby interfering with their maturation and reproduction, suggesting that in addition to their role as storage lipids, CPE can also serve as protective agents. CPE are also strong inhibitors of a variety of fatty acid desaturases in animals [18–21], and feeding animals with CPE -containing oilseeds, such as cotton seed meal, leads to accumulation of hard fats and other physiological disorders [20, 22, 23]. For the same reasons vegetable oils that contain CPE must be treated with high temperature hydrogenation before human consumption. These treatments add to processing costs and also result in the accumulation of undesirable trans-fatty acids. Therefore, reducing the levels of CPE in cotton seed oil by gene-silencing or other techniques could reduce processing costs and the associated production of undesirable trans fatty acids as well as increasing the value of processed seed meal for food consumption (US2010/0115669).

Cyclic fatty acids, especially CPA such as dihydrosterculic acid, are desirable for numerous industrial applications and therefore it would be useful to identify candidate enzymes for heterologous expression in production plants with the goal of optimizing the accumulation of CPAs. CPAs have physical characteristics somewhere in between saturated and mono unsaturated fatty acids. The strained bond angles of the carbocyclic ring are responsible for their unique chemistry and physical properties. Hydrogenation results in ring opening to produce methyl-branched fatty acids. These branched fatty acids have the low temperature properties of unsaturated fatty acids, but unlike unsaturated fatty acids, their esters are not susceptible to oxidation and are therefore ideally suited for use in lubricant formulations [24] (WO 99/18217). Moreover, the methyl branched fatty acids are an alternative to isostearic acids that are used as cosmetics. Oils with high levels of cyclopropene fatty acids self-polymerize at elevated temperatures because the cyclopropene ring is highly strained and readily opens in an exothermic reaction. This property makes CPE particularly suitable for the productions of coatings and polymers. Sterculic acid (18-carbon cyclopropene) also has potential applications as a biocide in fatty acid soap formulation (US2008/0155714A1).

In this study, we identify three CPS isoforms from cotton and analyze their expression in different tissues to help define their physiological roles. We also present an analysis of the consequences of over-expressing cotton GhCPS1, 2 and 3 in yeast, tobacco suspension cells and Arabidopsis.

Methods

Plant growth conditions and transgenic analyses

Arabidopsis and camelina plants were grown in walk-in-growth chambers at 22°C for 16 h photoperiod, and cotton plants were grown in the greenhouse at 28°C for 16 h photoperiod. The full length cDNA corresponding to GhCPS1[GenBank:574036.1], GhCPS2 [GenBank:574037.1] and GhCPS3[GenBank:574038.1] genes were PCR amplified using gene specific primers with restriction site-encoding linkers and subsequently digested and cloned into pYES2 (Invitrogen) via corresponding SacI and EcoRI restriction sites. For Arabidopsis and camelina transformation, the genes were cloned downstream of the phaseolin seed-specific promoter in binary vector pDsRed [25]. These binary vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation and were used to transform Arabidopsis via the floral dip method [26], and camelina through vacuum infiltration [27]. Seeds of transformed plants were screened under fluorescence, emitted upon illumination with green light from a X5 LED flashlight (Inova) in conjunction with a 25A red camera filter [25]. For tobacco Bright Yellow 2 (BY2) transformation, GhCPS1 was cloned into pBI121 using BamHI and SacI sites, and GhCPS2 and 3 were cloned into pBI121 using the XbaI and SacI restriction sites and transformed into BY2 cells. After 4-5 months kanamycin selection, stable transformed cell lines were collected 7 days after subculture and analyzed for fatty acid composition. The composition of pBI121-containing negative control lines were compared with lines transformed with SfCPS in pBI121.

Primers used in this study for:

Yeast expression

GCPS1-Y2F: ACCGGAGCTCAcca t g g a a g t g g c c g t g a t c g

GCPS2-Y2F: ACCGGAGCTC Acca t g g a a g t g g c g g t g a t c g

GCPS1+2-R: CCGGAATTC t c a a t c a t c c a t g a a g g a a t a t g c

GCPS3-Y2F: ACCGGAGCTC AccATGGGTa t g a a a a t a g c a g t g a t a g g a g g a g

GCPS3-R: CCGGAATTC t t a a g a a g c t g a g g g g a a g t c t t t

Arabidopsis transformation

GCPS1-5'PacI: tcccTTAATTAA a t g g a a g t g g c c g t g a t c g

GCPS2-5'PacI: tcccTTAATTAA a t g g a a g t g g c g g t g a t c g

GCPS1+2-3'XmaI: tcccCCCGGG t c a a t c a t c c a t g a a g g a a t a t g

SfCPS-5'PacI: tcccTTAATTAA a t g g g a g t g g c t g t g a t c g

SfCPS-3'XmaI: tcccCCCGGG t c a a t t a t c c g a g t a g g a a t a t g c

GCPS3-5'PacI: tcccTTAATTAA a t g a a a a t a g c a g t g a t a g g a g g a

GCPS3-3'XbaI: GCTCTAGA t t a a g a a g c t g a g g g g a a g t c t t t

Tobacco BY2 transformation

GCPS3-5'XbaI: GCTCTAGA a t g a a a a t a g c a g t g a t a g g a g g a

GCPS3-3'SacI: ACCGGAGCTC t t a a g a a g c t g a g g g g a a g t c t t t

GCPS2-5'XbaI: GCTCTAGA a t g g a a g t g g c g g t g a t c g

GCPS1+2-3'SacI: ACCGGAGCTC t c a a t c a t c c a t g a a g g a a t a t g

GCPS1-5'BamHI: CGCGGATCC a t g g a a g t g g c c g t g a t c g

SfCPS-5'XbaI: GCTCTAGA a t g g g a g t g g c t g t g a t c g

SfCPS-3'SacI: ACCGGAGCTC t c a a t t a t c c g a g t a g g a a t a t g c

Sequence homologous to the CPS sequences in lower case, flanking sequences in boldface, restriction site sequence underlined.

Phylogenetic and sequence analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of the cyclopropane fatty acid synthase (CPS) family was conducted by using full length protein sequences from cotton and cyclopropane fatty acid synthase from Sterculia, E. coli, Agrobacterium, Mycobacterium, and Arabidopsis. Full-length amino-acid sequences were first aligned by CLUSTALW version 2.0.12 (Additional file 1) [28] with default parameters (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw/), and imported into the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) package version 5.0 [29]. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method [30] implemented in MEGA, with the pair-wise deletion option for handling alignment gaps, and the Poisson correction model for computing distance. The final tree graphic was generated using TreeView program [31].

RNA extraction, Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR analyses

RNA from cotton leaf, flower, stem and seeds at different development stages were extracted according to Wu et al. [32] and RNA from cotton root was isolated using Qiagen's plant Mini RNA kit. RNA quality and concentration were determined by gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop spectroscopy. Reverse transcription (RT) was carried out using Qiagen's QuanTect Reverse Transcription Kit. Quantitative PCR analyses were carried out using Bio-RAD iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix as described in Additional file [2]. Primers ubiq7-1F (5'- GAAGGCATTCCACCTGACCAAC -3') and Ubiq7-1R (5'- CTTGACCTTCTTCTTCTTGTGCTTG -3') were used to amplify ubiquitin 7 as internal standard. Gene-specific primers used for qRT-PCR analysis were qGCPS-1F(5'- TTAAGTGGTCAACCGGCCATGCAA -3') and qGCPS-1R (5'-TTCTTTGGACTGGGCGGAACAGAA -3'), qGCPS2-1F (5'-ATATTCCCTGGAGGAACC CTG CTT-3') and qGCPS2-1R (5'-AAACCGGCAGCGCAGTAATCGAAA-3') for GhCPS2, and qGCPS3-1F (5'-ACTGGTTGCGAGGTGCATTCTGTT-3) and qGCPS3-1R (5'-TTGGAAAGCGCCAAGCACTGTTGA -3') for GhCPS3.

Fatty acid analyses

Yeast culture, expression induction, and fatty acid analyses were carried out as described [33]. Lipids were extracted in methanol/chloroform (2:1) from 0.1 g of fresh weight cotton tissue and internal standard heptadecanoic acid was added. The isolated lipid was methylated in 1% sodium methoxide at 50°C for 1 hr and extracted with hexane. To analyze the fatty acids of single seeds, fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were prepared by incubating the seeds with 35 μL 0.2M trimethylsulfonium hydroxide in methanol [34]. For analysis of CFA in BY2 cell lines, FA were extracted from ~0.1 g of BY2 callus tissue, FAMEs were prepared as described above for cotton tissue, or FA dimethyloxazoline (DMOX) derivatives were prepared in a one-pot reaction in which FA are reacted with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol in a nitrogen atmosphere at 190°C for 4 hours [35]. Lipid profiles and acyl group identification were analyzed on a Hewlett Packard 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a 5973 mass selective detector (GC/MS) and either Agilent J&W DB 23 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 μm × 0.25 μm) or SUPELCO SP-2340 (60 m × 0.25 μm × 0.20 μm) column. The injector was held at 225°C and the oven temperature was varied from 100-160°C at 25°C/min, then 10°C/min to 240°C. The percentage values were converted to mole percent and presented as means of at least three replicates.

Results

The cotton cyclopropane fatty acid synthase family consists of three highly conserved members

A database search of the cotton genome database (http://cottondb.org/) identified three genes predicted to encode proteins with high sequence similarity to Sterculia CPS (Figure 1). The predicted polypeptides encoded by the cotton CPS isoforms range from 865 to 873 amino acids. Sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis of the different isozymes conducted using the MEGA5 program revealed that the GhCPS1 and 2 isozymes are the most similar, showing 97% identity at the amino acid level, and group in a clade with Sterculia CPS. GhCPS1 and 2 showed 82% and 84% identity to Sterculia CPS, respectively. The GhCPS3 protein showed divergence from these 3 synthases, arising from a completely separate branch (Figure 1). Sequence comparisons showed GhCPS3 had 64% identity with GhCPS1 and 65% with GhCPS2.

Phylogenetic tree of cyclopropane synthase genes revealing evolutionary sequence relationships. The tree was constructed by neighbor-joining distance analysis. Line lengths indicate the relative distances between nodes. Sequences of characterized enzymes and CPS homologues from Arabidopsis and cotton were used for alignment, pcaA, mycolic acid synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv [NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000962.2]; cmaA1, Cyclopropane mycolic acid synthase 1 from Mycobacterium bovis AF2122/97 [NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_002945.3]; AtCPs, cyclopropane synthase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (AGR-C-3601p); EcCPS, cyclopropane synthase from E.Coli [NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000913]; cmaA2, Cyclopropane mycolic acid synthase 2 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis [NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_215017.1]; mmaA2, Cyclopropane mycolic acid synthase MmaA2 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis [NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_215158.1].

The cotton CPSs have two enzymatic domains as reported for the Sterculia CPS [8]; the carboxy terminus encodes the CPS domain and catalyzes the synthesis of dihydrosterculate while the amino terminus encodes a distinct oxidase domain of unknown function. A sequence proposed to play a role in S-AdoMet binding, VL(E/D)xGxGxG [36, 37], was found in GhCPS3 as ILEIGCGWG and in a more degenerate form (DxGxGxG) in GhCPS1 and 2. Given that S-AdoMet binding and methyl group transfer is the only known function shared between CPS and other S-AdoMet binding enzymes, this segment of the GhCPSs seems very likely to be involved in binding this substrate. It should be noted that all CPS coding sequences lack the phenylalanine residue of the FxGxG, proposed by both Lauster [38] and Smith et al. [39]. However, this motif has been found only in methyltransferases that act on nucleic acids [37].

Active site conservation

The crystallized M. tuberculosis CPS structure shows a bicarbonate ion hydrogen-bonded to five active-site residues [15], including two interactions via backbone amides. In E.coli CPS C139, I268, E239, H266, and Y317 are strictly conserved within all non-plant CPSs [16]. In cotton, the amino acids corresponding to E. Coli I268, E239, and Y317 are conserved in all 3 GhCPS genes, i.e. I739, E710, Y794 for GhCPS1; I731, E702, Y786 for GhCPS2 and I736, E707, Y791 for GhCPS3. However, H266 has been substituted for Q in GhCPS (Q737, I729 and Q734 respectively). Interestingly, C139 remains the same in GhCPS3 as C602, but is substituted for S in the other two GhCPS (S602 in GhCPS1 and S595 in GhCPS2). An E. coli C139S mutant is less active than the wild-type enzyme (its catalytic efficiency is 31%), but addition of bicarbonate increases its Kcat, by a factor of two [16].

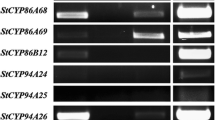

The GhCPS genes exhibit tissue-specific differences in their expression

To provide clues as to possible physiological roles of the three isozymes, their expression patterns in various tissues of cotton plants were examined. Quantitative reverse transcriptase (qRT)-PCR analysis of RNA from leaf, stem, root, flower and seeds at different development stages using gene-specific primers for the three isoforms revealed that GhCPS1 and 2 are highly expressed in root, stem, and flower. Both GhCPS1 and 2 showed low transcription levels in leaf and seeds at early development stages, i.e., from 0 to 25 day post anthesis (dpa) (Figure 2 A and B). In contrast, GhCPS3 showed highest transcription in leaf and flower but reduced levels in root and stem (Figure 2, C). All three GhCPS gene-transcript levels increased with seed development (Figure 2).

GhCPS expression level in different tissues. qRT-PCR analysis of putative cyclopropane synthase GhCPS1 (A), GhCPS2 (B) and GhCPS3 (C) among different tissues of cotton: leaf, stem, root, flower and seeds at different developing stages. The relative expression levels are reported relative to the expression of the ubiquitin 7 transcript. Data represents mean of triplicate measurements, error bar represents standard deviation.

Expression of GhCPS1 and 2 correlates with cyclic fatty acid accumulation levels

The FA profile of leaf, stem, root, flower and seeds at different development stages were determined to evaluate how they differed in their fatty acid compositions (Table 1). In root, stem and flower tissues, cyclic fatty acids made up about 19.2%, 9.9% and 4.0% of total fatty acids, respectively. Of these fatty acids, malvalic acid (7-(2-octyl-1-cyclopropenyl) heptanoic acid) was the most abundant, accounting for 11.9%, 6.9% and 3.0% of total fatty acids in root, stem and flower tissues, respectively. Cyclopropane and cyclopropene fatty acids were present at less than 2% in cotton leaf and seed tissues. With seed development, cyclic fatty acid increased to1.5% at 40 dpa seeds from less than 1.0% in 0, 5, 10 and 25 dpa seeds, and decreased to 1.2% in 50 dpa seeds.

In cotton tissues the abundance of GhCPS1 and 2 transcripts in different tissues is in general agreement with the cyclic fatty acid distribution, while GhCPS3 is expressed at very low levels in the root and stem tissues which are rich in the cyclic fatty acid. This suggests that GhCPS1 and 2 contribute to the CFA production in cotton. Cyclic fatty acids are synthesized very early in seed development, which was detected as early as 0 dpa in the ovule, and increased to peak at 40 dpa and then decreased a little at 50 dpa. This pattern is consistent with the expression pattern of GhCPS1, 2 and 3, but we cannot rule out GhCPS3 involvement in CFA production in the seed.

Expression of GhCPS1 and 2 in yeast demonstrates their physiological activity

To test whether the identified GhCPSs have enzymatic activity, the 3 genes were cloned into pYES2 vector and transformed into host strain YPH499. In addition to the authentic GhCPS2 sequence, a mutant, GhCPS2 I733T was identified and since the mutant point I733T is only one amino acid from the biocarbonate ion binding site, we decided to include it in our analysis. As shown in Figure 3, the fatty acid composition of yeast expressing GhCPS1 shows the production of two extra fatty acids relative to the control, the 17:0 CFA and 19:0 CFA. 17:0 CFA is identified by its mass ion from GC/MS. As shown in Figure 4, the GhCPS1 overexpression strain converted 16:1 FA to 2.96% of 17CFA and 18:1 FA into 2.32% of 19CFA, i.e., yielding a total of 5.28% CFA accumulation. The expression of GhCPS1 resulted in almost twice the CFA accumulation reported for the expression of the CPS from Sterculia [8]; SfCPS produced 2.36% of 17CFA and 0.82% of 19CFA, i.e., 3.18% total CFA. Expression of GhCPS2 resulted in only 0.36% CFA accumulation, while the expression of GhCPS3 didn't result in detectable levels of CFAs. Interestingly, the fortuitously obtained GhCPS2 I733T mutant resulted in the accumulation of 2.50% 17C and 19C cyclopropane, i.e., approximately 10-fold that of the WT GhCPS2. These results demonstrate that GhCPS 1 and 2 are indeed active CPSs that can act on both 16:1 and 18:1 fatty acid substrates to produce both 17C and 19C cyclopropane fatty acids.

Deletion of the N-terminal oxidase domain decreases CPS activity

Compared to bacterial CPS, GhCPS contain a ~400-amino acids-long N-terminal extension, homologous to oxidases that possesses an FAD-binding motif. In order to deduce the function of the oxidase domain of cotton CPS, different lengths of the N-terminal extension were deleted and the resulting constructs were expressed in yeast. After a 2-days of induction, a full length GhCPS1 yielded 2.94% 17CFA and 2.36% 19CFA, totaling 5.30% CFA. When the entire oxidase portion (409 aa) was deleted, the GhCPS1 still retained about 30% of the activity demonstrating that the oxidase activity is not necessary for CPS activity, but that it enhances CPS activity by an as yet unknown mechanism. Surprisingly, deletion of part of the oxidase domain, reduced CFA accumulation more than a total deletion (Figure 5), possibly by making the mRNA unstable or by incorrect folding of the protein, destabilizing it. Further deletion beyond the oxidase domain, i.e., into the N-terminal portion of the CPS domain, resulted in additional decreases in activity, with only 1.21% CFA accumulating upon deletion of 426 aa and 0.84% CFA upon deletion of 433 aa.

Effect of N-terminal deletions on the CPS activity of GhCPS1. Different portions of the N-terminal domain ranging from 21aa to 433 aa were deleted from GhCPS1, and their effects on CFA production analyzed. Both 17:0 and 19:0 CFAs were calculated as a percentage of the total fatty acids. The values represent the mean and standard deviation of three replicates.

Co-expression of the Agrobacterium oxidase with the E. Coli CPS resulted in lower CFA accumulation in yeast compared to expression of the CPS alone. A similar decrease was found when the Agrobacterium oxidase was fused with E. Coli CPS protein. Fusion of a plant CPS N-terminal oxidase to E.Coli CPS also inhibited its ability to produce CFA (data not shown). These results demonstrate that unlike the cotton CPSs, E.Coli CPS activity is not enhanced by the oxidase domain. We cloned the Agrobacterium, gene AGR-C-3599p (N-terminal homolog to plant CPS) and AGR-C-3601p (C-terminal homolog to plant CPS) that was located 802 bp upstream of AGR-C-3599p. We also failed to detect any CFA from the ACPS over expression in yeast, and neither co-expression of these two proteins in yeast nor the fusion of these two polypeptides into a single polypeptide yielded any cyclopropane fatty acids (data not shown).

Heterologous expression of GhCPS1 and 2 results in CFA accumulation in plants

The CPS genes were transformed into Arabidopsis fad2/fae1 background with the GhCPS1 transgenic seeds yielding about 1.0% of 19C cyclopropane. No significant accumulation of cyclopropane products was detected in GhCPS2 and 3 over expression lines (Figure 6). Consistent with the GhCPS expression in yeast, a trace amount of cyclopropane was detected upon the expression of the SfCPS and GhCPS2 I733T mutant. Expression of CPSs in Arabidopsis seeds didn't lead to significant changes in other fatty acid composition and the oil content (data not shown).

When these genes were expressed in BY2 cell lines, ~1.0% of 19C cyclopropane was produced in GhCPS1 lines and SfCPS lines, and only a trace amount of CFA was detected in GhCPS2 transformed BY2 lines. No cyclopropane fatty acid was detected in lines transformed with GhCPS3, the chromatograms of which were indistinguishable from control pBI121-containing lines. In one of the 16 GhCPS2 I733T lines, 2.9% of CFA was detected.

These results demonstrate that GhCPS1 and 2 can cause the accumulation of CPA FA upon heterologous expression in plants.

Discussion

Blast searching of the cotton genome database using the Sterculia CPS gene resulted in the identification of three cotton CPS homologous genes (GhCPS1, 2, 3). GhCPS1 and 2 show high similarities to the published SfCPS gene and their expression patterns correlate closely with CFA distributions in a variety of tissues. In addition, we confirmed their biochemical identity as cyclopropane synthases in yeast and plant.

Interestingly, GhCPS3's transcription level is relatively low in roots and stems where higher abundance of CFA is found. In addition, when heterologously expressed GhCPS3 did not result in detectable CFA accumulation in yeast, tobacco BY2 cell lines, or in Arabidopsis seeds. A number of plant sequences are related to GhCPS3; for instance, in Arabidopsis, 5 genes clustered in the same clade with GhCPS3 (Fig 1) and are more closely related to GhCPS3 than to SfCPS or to GhCPS 1 and 2. CPA and CPE have not been reported in Arabidopsis so far consistent with our analysis of Arabidopsis seeds and leaves in which we failed to identify any cyclopropane or cyclopropene fatty acids (data not shown). Since GhCPS3 and its Arabidopsis homologues are mainly expressed in leaf, it is possible that they catalyze the formation of other cyclopropanated products [9].

The role of the N-terminal oxidase portion of the plant-type CPS gene remains to be determined. From an evolutionary point of view, it is interesting to speculate on the origin of the cyclopropane synthases that contain the oxidase domain at the N-terminus. The oxidase gene and CPS gene are located adjacent to one another in the genomes of Agrobacterium and Mycobacteria; in plants the genes are fused to form a single product; taken together this suggests that the N-terminal domain in plants and its homologs in bacteria may play a role(s) related to cyclopropanation [9]. There is a conserved FAD-binding motif in the first 21 aa of the plant oxidase domain. It is hard to envisage how a redox system such as a FAD-containing protein could be involved in the catalytic reaction of methylene addition. After removal of the oxidase portion, the C-terminal CPS portion of GhCPS1 still retains 30% of its activity, showing that the oxidase activity is not necessary for function but that an intact oxidase domain somehow enhances activity perhaps by conferring stability to the CPS polypeptide. Cotton CPS antibodies would be helpful in distinguishing whether the reduction of activity upon partial, or complete deletion, of the oxidase domain results from destabilization of the enzyme or from loss of catalytic activity. It is possible that the oxidase portion plays a potential role in either the desaturation of dihydrosterculic acid to produce sterculic acid or the α-oxidation of the product to form malvalic acid.

Malvalic acid is a predominant CPE in cotton. No chain-shortened CPA was found when GhCPSs are expressed in yeast, tobacco BY2 cell lines, or fad2/fae1 Arabidopsis seeds. The data also show that the presence of CPA was insufficient to induce α-oxidation in these systems. Since neither CPE nor α-oxidation products were observed, we conclude that additional gene products are required for these functions.

A variety of bacteria initiate the cyclopropanation of fatty acids in the stationary phase or upon exposure to low pH [6, 40, 41], osmotic stress [42, 43] and high temperature [44]. The conversion of unsaturated fatty acids into the corresponding CFAs reduces the levels of unsaturated fatty acids in membranes and therefore contributes to a reduction of the membrane fluidity which renders lipid bilayers more rigid [45]. Cyclization of fatty acid acyl chains is therefore generally regarded as a means to reduce membrane fluidity to adapt the cells for adverse conditions [6]. The content of cyclopropane fatty acids with 25 carbon atoms is correlated with early growth in spring for Galanthus nivalis L. and Anthriscus silvestris L. [46]. Lipids esterified with long chain cyclopropane fatty acids could contribute to the physiological adaptations of early spring plants and drought-tolerant plants by reducing membrane permeability to solvent [46].

CPE inhibited fatty acid desaturation in two fungi of interest to plant pathologists and CPE from Sterculia foetida affected U. maydis, the basidiomycete responsible for corn smut growth and morphology, suggesting that CPE serves as antifungal agent [47]. Study of gene expression changes in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum-infected cotton seedlings identified GhCPS2 (i.e., CD486555) as having increased expression in cotton roots at 3 days post-infection, together with a bacterially induced lipoxygenase. This makes GhCPS2 one of the few potential defense-related genes induced in infected roots and putative stress-related genes encoding proteins such as glutathione S-transferase (GST) 18 and nitropropane dioxygenase [48].

Conclusions

We have shown that both GhCPS1 and 2 contribute to CFA accumulation in cotton seeds; but GhCPS1 accounts for the majority of CFA accumulation in roots and stems. The information presented herein has potential uses for two distinct biotechnological applications. It is highly desirable to target both GhCPS1 and 2 for suppression to reduce the CPE content of cottonseed meal for use as animal feed. Conversely, to facilitate CPA accumulation for use as oleochemical feedstocks, our data suggests GhCPS1 to be the best choice for heterologous expression in a production plant.

References

Vickery JR: Fatty-Acid Composition of Seed Oils from 10 Plant Families with Particular Reference to Cyclopropene and Dihydrosterculic Acids. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1980, 57: 87-91. 10.1007/BF02674370.

Badami RC, Patil KB: Structure and occurrence of unusual fatty acids in minor seed oils. Prog Lipid Res. 1980, 19: 119-153. 10.1016/0163-7827(80)90002-8.

Ralaimanarivo A, Gaydou EM, Bianchini JP: Fatty-Acid Composition of Seed Oils from 6 Adansonia Species with Particular Reference to Cyclopropane and Cyclopropene Acids. Lipids. 1982, 17: 1-10. 10.1007/BF02535115.

Vickery JR, Whitfield FB, Ford GL, Kennett BH: The Fatty-Acid Composition of Gymnospermae Seed and Leaf Oils. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1984, 61: 573-575. 10.1007/BF02677035.

Gaydou EM, Ralaimanarivo A, Bianchini JP: Cyclopropanoic Fatty-Acids of Litchi (Litchi-Chinensis) Seed Oil - a Reinvestigation. J Agr Food Chem. 1993, 41: 886-890. 10.1021/jf00030a009.

Grogan DW, Cronan JE: Cyclopropane ring formation in membrane lipids of bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997, 61: 429-441.

Barry CE, Lee RE, Mdluli K, Sampson AE, Schroeder BG, Slayden RA, Yuan Y: Mycolic acids: structure, biosynthesis and physiological functions. Prog Lipid Res. 1998, 37: 143-179. 10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00008-3.

Bao X, Katz S, Pollard M, Ohlrogge J: Carbocyclic fatty acids in plants: biochemical and molecular genetic characterization of cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis of Sterculia foetida. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99: 7172-7177. 10.1073/pnas.092152999.

Bao X, Thelen JJ, Bonaventure G, Ohlrogge JB: Characterization of cyclopropane fatty-acid synthase from Sterculia foetida. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 12846-12853. 10.1074/jbc.M212464200.

Rahman MD, Ziering DL, Mannarelli SJ, Swartz KL, Huang DS, Pascal RA: Effects of sulfur-containing analogues of stearic acid on growth and fatty acid biosynthesis in the protozoan Crithidia fasciculata. J Med Chem. 1988, 31: 1656-1659. 10.1021/jm00403a029.

George KM, Yuan Y, Sherman DR, Barry CE: The biosynthesis of cyclopropanated mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Identification and functional analysis of CMAS-2. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270: 27292-27298. 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27292.

Yuan Y, Barry CE: A common mechanism for the biosynthesis of methoxy and cyclopropyl mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 12828-12833. 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12828.

Glickman MS, Cox JS, Jacobs WR: A novel mycolic acid cyclopropane synthetase is required for cording, persistence, and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Cell. 2000, 5: 717-727. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80250-6.

Glickman MS: The mmaA2 gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes the distal cyclopropane synthase of the alpha-mycolic acid. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 7844-7849. 10.1074/jbc.M212458200.

Huang CC, Smith CV, Glickman MS, Jacobs WR, Sacchettini JC: Crystal structures of mycolic acid cyclopropane synthases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 11559-11569. 10.1074/jbc.M111698200.

Courtois F, Ploux O: Escherichia coli cyclopropane fatty acid synthase: is a bound bicarbonate ion the active-site base?. Biochemistry. 2005, 44: 13583-13590. 10.1021/bi051159x.

Kleiman R, Earle FR, Wolff IA: Dihydrosterculic Acid, a Major Fatty Acid Component of Euphoria Longana Seed Oil. Lipids. 1969, 4: 317-10.1007/BF02530999.

Fogerty AC, Johnson AR, Pearson JA: Ring position in cyclopropene fatty acids and stearic acid desaturation in hen liver. Lipids. 1972, 7: 335-338. 10.1007/BF02532651.

Fabrias G, Gosalbo L, Quintana J, Camps F: Direct inhibition of (Z)-9 desaturation of (E)-11-tetradecenoic acid by methylenehexadecenoic acids in the biosynthesis of Spodoptera littoralis sex pheromone. J Lipid Res. 1996, 37: 1503-1509.

Allen E, Johnson AR, Fogerty AC, Pearson JA, Shenstone FS: Inhibition by cyclopropene fatty acids of the desaturation of stearic acid in hen liver. Lipids. 1967, 2: 419-423. 10.1007/BF02531857.

Waltermann M, Steinbuchel A: In vitro effects of sterculic acid on lipid biosynthesis in Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630 and isolation of mutants defective in fatty acid desaturation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000, 190: 45-50.

Phelps RA, Shenstone FS, Kemmerer AR, Evans RJ: A Review of Cyclopropenoid Compounds: Biological Effects of Some Derivatives. Poult Sci. 1965, 44: 358-394.

Page AM, Sturdivant CA, Lunt DK, Smith SB: Dietary whole cottonseed depresses lipogenesis but has no effect on stearoyl coenzyme desaturase activity in bovine subcutaneous adipose tissue. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1997, 118: 79-84. 10.1016/S0305-0491(97)00027-8.

Kai Y, Pryde EH: Production of Branched-Chain Fatty-Acids from Sterculia Oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1982, 59: 300-305. 10.1007/BF02662231.

Pidkowich MS, Nguyen HT, Heilmann I, Ischebeck T, Shanklin J: Modulating seed beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II level converts the composition of a temperate seed oil to that of a palm-like tropical oil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 4742-4747. 10.1073/pnas.0611141104.

Clough SJ, Bent AF: Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16: 735-743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x.

Lu C, Kang J: Generation of transgenic plants of a potential oilseed crop Camelina sativa by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 2008, 27: 273-278. 10.1007/s00299-007-0454-0.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22: 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24: 1596-1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092.

Saitou N, Nei M: The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987, 4: 406-425.

Page RD: TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996, 12: 357-358.

Wu YR, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES: A quick and easy method for isolating good-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) tissues. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2002, 20: 213-218. 10.1007/BF02782456.

Broadwater JA, Whittle E, Shanklin J: Desaturation and hydroxylation. Residues 148 and 324 of Arabidopsis FAD2, in addition to substrate chain length, exert a major influence in partitioning of catalytic specificity. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 15613-15620. 10.1074/jbc.M200231200.

Butte W, Eilers J, Kirsch M: Trialkysulfonium-hydroxides and trialkylselonium-hydroxides for the pyrolytic alkylation of acidic compounds. Anal Lett. 1982, 15: 841-850.

Christie WW, (Ed.): Lipid Analyalysis: Isolation, Separation, Identification and Structural Analysis of Lipids. 3rd edition. Bridgwater, England: The Oily Press, 2003.

Ingrosso D, Fowler AV, Bleibaum J, Clarke S: Sequence of the D-aspartyl/L-isoaspartyl protein methyltransferase from human erythrocytes. Common sequence motifs for protein, DNA, RNA, and small molecule S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 1989, 264: 20131-20139.

Haydock SF, Dowson JA, Dhillon N, Roberts GA, Cortes J, Leadlay PF: Cloning and sequence analysis of genes involved in erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea: sequence similarities between EryG and a family of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Mol Gen Genet. 1991, 230: 120-128. 10.1007/BF00290659.

Lauster R, Trautner TA, Noyer-Weidner M: Cytosine-specific type II DNA methyltransferases. A conserved enzyme core with variable target-recognizing domains. J Mol Biol. 1989, 206: 305-312. 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90480-4.

Smith HO, Annau TM, Chandrasegaran S: Finding sequence motifs in groups of functionally related proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87: 826-830. 10.1073/pnas.87.2.826.

Budin-Verneuil A, Maguin E, Auffray Y, Ehrlich SD, Pichereau V: Transcriptional analysis of the cyclopropane fatty acid synthase gene of Lactococcus lactis MG1363 at low pH. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005, 250: 189-194. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.007.

Grandvalet C, Assad-Garcia JS, Chu-Ky S, Tollot M, Guzzo J, Gresti J, Tourdot-Marechal R: Changes in membrane lipid composition in ethanol- and acid-adapted Oenococcus oeni cells: characterization of the cfa gene by heterologous complementation. Microbiology. 2008, 154: 2611-2619. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016238-0.

Guillot A, Obis D, Mistou MY: Fatty acid membrane composition and activation of glycine-betaine transport in Lactococcus lactis subjected to osmotic stress. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000, 55: 47-51. 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00193-8.

Monteoli-Vasanchez M, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Russell NJ: The Effect of Salinity and Compatible Solutes on the Biosynthesis of Cyclopropane Fatty-Acids in Pseudomonas halosaccharolytica. J Gen Microbiol. 1993, 139: 1877-1884.

Dubois-Brissonnet F, Malgrange C, Guerin-Mechin L, Heyd B, Leveau JY: Changes in fatty acid composition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442 induced by growth conditions: consequences of resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds. Microbios. 2001, 106: 97-110.

Loffhagen N, Hartig C, Geyer W, Voyevoda M, Harms H: Competition between cis, trans and cyclopropane fatty acid formation and its impact on membrane fluidity. Eng Life Sci. 2007, 7: 67-74. 10.1002/elsc.200620168.

Kuiper PJC, Stuiver B: Cyclopropane fatty acids in relation to earliness in spring and drought tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. 1972, 49: 307-309. 10.1104/pp.49.3.307.

Schmid KM, Patterson GW: Effects of cyclopropenoid fatty acids on fungal growth and lipid composition. Lipids. 1988, 23: 248-252. 10.1007/BF02535466.

Dowd C, Wilson IW, McFadden H: Gene expression profile changes in cotton root and hypocotyl tissues in response to infection with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004, 17: 654-667. 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.6.654.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Carl Andre at Brookhaven National Laboratory for critical reading of our manuscript, Prof. John Ohlorogge at Michigan State University for SfCPS gene, Prof. Kent Chapman at the University of North Texas for providing us with the cotton seeds, and Mr. Kevin Lutke from Donald Danforth Plant Science Center who helped with the BY2 transformation. This work was supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy (JS), and by the National Science Foundation (Grant DBI 0701919) (RR and X-HY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JS conceived of and provided the initial design of the study. X-HY and RR performed the research. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12870_2011_888_MOESM1_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 1: Sequence alignment of CPS. Amino acid sequence alignment of CPS from different organisms (DOCX 22 KB)

12870_2011_888_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: qPCR experiments/MIQE. Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (DOC 81 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, XH., Rawat, R. & Shanklin, J. Characterization and analysis of the cotton cyclopropane fatty acid synthase family and their contribution to cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis. BMC Plant Biol 11, 97 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-97

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-97