Abstract

Background

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a potent vasoconstrictor, and astrocytic ET-1 is reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemic injury and cytotoxic edema. However, it is still unknown whether astrocytic ET-1 also contributes to vasogenic edema and vasospasm during subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). In the present study, transgenic mice with astrocytic endothelin-1 over-expression (GET-1 mice) were used to investigate the pathophysiological role of ET-1 in SAH pathogenesis.

Results

The GET-1 mice experienced a higher mortality rate and significantly more severe neurological deficits, blood–brain barrier breakdown and vasogenic edema compared to the non-transgenic (Ntg) mice following SAH. Oral administration of vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist, SR 49059, significantly reduced the cerebral water content in the GET-1 mice. Furthermore, the GET-1 mice showed significantly more pronounced middle cerebral arterial (MCA) constriction after SAH. Immunocytochemical analysis showed that the calcium-activated potassium channels and the phospho-eNOS were significantly downregulated, whereas PKC-α expression was significantly upregulated in the MCA of the GET-1 mice when compared to Ntg mice after SAH. Administration of ABT-627 (ETA receptor antagonist) significantly down-regulated PKC-α expression in the MCA of the GET-1 mice following SAH.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that astrocytic ET-1 involves in SAH-induced cerebral injury, edema and vasospasm, through ETA receptor and PKC-mediated potassium channel dysfunction. Administration of ABT-627 (ETA receptor antagonist) and SR 49059 (vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist) resulted in amelioration of edema and vasospasm in mice following SAH. These data provide a strong rationale to investigate SR 49059 and ABT-627 as therapeutic drugs for the treatment of SAH patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a subset of stroke, which occurs due to bleeding between the brain and the meninges in the subarachnoid space. Patients with SAH suffer from fatal complications, such as rapid development of cerebral vasogenic brain edema, and rise of intracranial pressure, mainly due to hematoma [1]. One third of patients with SAH also suffer from secondary ischemia due to the delayed narrowing of intracranial arteries (vasospasm). Vasospasm results in the interruption of blood flow to the vital parts of the brain causing morbidity and mortality in up to 30% patients [2]. Vasopressin receptor (V1 or V2) antagonists have been evaluated in numerous studies using different brain injury paradigms to investigate their effects on attenuating edema development after brain injury in animal models [3–5]. Until now, the pathophysiological aspects and mechanisms of SAH-induced vasospasm have not been completely elucidated, and the treatment for SAH-induced vasospasm remains one of the major challenges in neurosurgery.

Break down of red blood cells and release of oxyhemoglobin is the putative cause of delayed vasospasm after SAH [6–9]. One of the oxyhemoglobin-mediated cerebral vasospasm mechanisms is the release of a potent vasoconstricting agent, endothelin-1 (ET-1) [10, 11]. ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor originally isolated from aortic endothelial cells. However, ET-1 has also been detected in several other types of brain cells, including endothelial cells, neurons and astrocytes [12–14]. It has been demonstrated that activated mononuclear leukocytes are involved in ET-1 production under SAH [15]. Additionally, the release of ET-1 can be stimulated by oxyhemogloblin or thrombin in endothelial and smooth muscle cells [16]. However, it is still unclear whether astrocytic ET-1 and the mechanisms of its release are responsible for cerebral vasospasm development. Several clinical studies have established a correlation between elevated ET-1 levels in plasma and cerebral spinal fluid, and cerebral vasospasm-mediated ischemic damage after SAH [17–19], indicating that ET-1 may also be produced during delayed ischemia after SAH.

Astrocytic ET-1 has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemic injury. Previously, we have demonstrated that transgenic mice (GET-1 mice) that over-express endothelin-1 (ET-1) specifically in the astrocytes are more susceptible to brain damage, including increased infarct volume, hemispheric swelling as well as cerebral water content, upon transient focal ischemia induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). We have also demonstrated that GET-1 mice develop more severe cytotoxic edema when induced by water intoxication [20, 21]. However, it is still unclear whether astrocytic ET-1 also plays an important role in vasogenic edema formation.

In the present study, transgenic mice with astrocytic endothelin-1 (GET-1 mice) over-expression were used to investigate the pathophysiological role(s) of ET-1 in SAH pathogenesis with the aim of dissecting the mechanisms involved in the formation of secondary ischemia in SAH. A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in SAH formation may help in formulation of therapeutic strategies for the treatment and management of the disease.

Methods

Mouse subarachnoid hemorrhage model

Both Ntg and GET-1 mice were housed under controlled diurnal lighting conditions and allowed free access to food and water. The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research in the University of Hong Kong.

SAH was induced in mice by the artery puncture method as previously described [22]. In brief, age-matched Ntg or GET-1 mice were anesthetized with gas (2% halothane in 70% N2O/30% O2 for induction and 1% halothane in 70% N2O/30% O2 for maintenance) [23]. Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was monitored and recorded with a Laser-Doppler system (PeriFlux 5001 and Perisoft software) during the whole surgical procedure to confirm successful SAH induction. The average value of rCBF was recorded one minute before induction of SAH served as the control value. SAH was induced, and rCBF was recorded for 20 minutes after SAH induction. The rectal temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C with a temperature control system (FHC, Brunswick, ME, USA). The right carotid artery was identified along with all its extracranial branches, and the external carotid artery was dissected. A sharpened 5–0 monofilament suture was advanced into the external carotid artery past the common carotid bifurcation and into the internal carotid artery. The suture was advanced distally into the intracranial internal carotid artery until resistance was felt and then pushed 3 mm further through the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA) near its intracranial bifurcation. The suture was then withdrawn into the external carotid artery immediately, which allowed reperfusion of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) leading to SAH. After the surgery, the mice were returned to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) to facilitate recovery from anesthesia.

Neurological evaluation following SAH

A subset of animals was used for neurological evaluation in the SAH experiment. A 100-point neurological scoring system (scoring scale 0 to 100), which assessed the general behavioral deficit, cranial nerve reflexes deficit, motor deficit, sensory deficit and coordination deficit, was used to evaluate the neurological deficit of mice 24 hours after SAH and continued for three days [24]. A general behavioral score (0–40) was derived from spontaneous activity and respirations. A cranial nerve reflex score (0–20) was derived from examination of olfactory, vision, blinding reflex, whisker movement and hearing response to stimulus. A motor score (0–10) was derived from examination of symmetry of limb movement. A sensory score (0–10) was derived from the response of mice while their tails were being pinched. A coordination score (0–20) was derived from examination of traveling ledge balance, righting reflex, front paws reaching and retreatment response. Mice were sacrificed afterwards and brain tissues were collected for further analysis. The behavioral tests were performed blinded to the genotypes.

Perfusion-fixation and vascular diameter measurement

At 72 hours after SAH induction, when vasospasm has been reported to peak in mice models [25], cerebral vascular perfusion and vascular diameter measurement were performed as described previously [26]. After neurological deficit evaluation, mice were anesthetized. The chest was opened, and the aorta was cannulated with a blunted 20-gauge needle. Flexible plastic tubing connected to the needle was used to deliver infusion solutions by manual pulsatile syringe pressure, and the tubing was connected to a 30-ml syringe. An incision was made in the right atrium to allow outflow of perfusion solutions. 20 ml of 0.9% NaCl was infused followed by 10% formalin and gelatin-india ink solution. The dead mice were refrigerated for 24 hours to allow gelatin solidification, and thereafter the brains were harvested and stored in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde. The cerebral vasculature was photographed by using a video-linked microscope (Fluorescence Stereo Microscope, MZ FLIII, Leica). At 72 hours after SAH induction, the diameter of the left and right MCA was measured at the site 1 mm distal to the MCA-ACA bifurcation [27]. All procedures were performed blinded to the genotypes.

Water content measurement

Different groups of animals were used for the water content measurement. Brain tissue was removed for the brain water content analysis at 24 hours after SAH. The brain was weighted immediately to obtain the wet weight. The brain was then dried in an oven at 105°C for 48 hours and weighed again to obtain the dry weight. The percentage of water content was calculated as [(wet weight-dry weight)/wet weight] × 100% [28].

Evans Blue extravasation

Different groups of animals were used for the Evans Blue (EB) extravasation. On Day 3 (72 hours) after SAH induction, 0.1 ml of 4% EB in saline was injected intravenously into the mice and allowed to circulate for 3 hours [29]. For extraction of EB from brain, the brain was placed in 1 ml PBS and homogenized by sonication. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 mins and 0.5 ml supernatant was added to an equal volume of trichloroacetic acid. The mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight and centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4°C for 30 mins after incubation. The supernatant was collected, and EB was measured at an excitation wavelength of 620 nm and an emission wavelength of 680 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer. EB concentrations were calculated using the standard curve, and expressed as μg/g brain tissue [30].

Immunocytochemical (ICC) analysis

On Day 3 after SAH induction, brain samples were collected after neurological evaluation, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. MCA was isolated according to a published protocol [31]. In brief, the first cut was made at the groove between the forebrain and cerebellum (−4.5 mm from bregma), then the second cut at −6.5 mm from bregma, and the final cut at 3 mm anterior to the groove (−1.5 mm from bregma). The anterior portion of the forebrain was then turned 90° and two sagittal cuts were made at the midline crossing the olfactory tract to expose the cross section of the MCA [31]. 7 μm thick coronal brain slices were used for the ICC study. Brain sections were incubated with antibodies against GFAP (1:2000, Z0334, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA), nNOS (1:200, 610310, BD Transduction Lab., USA), eNOS (1:200, 610298, BD Transduction Lab., USA), p-eNOS (1:100, 9571, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), ETAR (1:100, 324758, Calbichem, Merck, Germany), Maxi K+α (1:500, 444910, Cabiochem, Merck, Germany ), PKC-α (1:500, abcam ab4124, UK) and endothelin 1 (1:250, abcam ab2786, UK). Signals were visualized by Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA, USA). All the conditions were followed as described in our previous study [20].

Quantification of ICC photomicrographs

Pictures of the brain sections with positive staining (GFAP: magnified 50×; MCA: magnified 100×) were analyzed with the software ImageJ [32]. For analyzing the staining of the MCA, the entire vascular wall of the MCA with staining was marked and the intensity of the staining was measured [33]. The value was expressed as mean ± SEM. All immunocytochemical photomicrograph quantifications were performed in a blinded manner and the results were expressed relative to Ntg sham group, which were arbitrarily assigned a value of 100%.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from the brains of sham and SAH groups of Ntg and GET-1 mice after 3 days. The brain tissues were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% NP-40, plus proteinase inhibitor cocktail). Homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C, 3000 g for 5 mins, and the supernatant was used for the Western blot analysis. Blots were incubated with antibodies against PKC-α (1:500, ab4124, abcam, UK), phospho-PKC-α (1:1000, Cat. no. #9375, Cell Signaling) and α-tubulin (1:5000, sc-5286, Santa Cruz). Signals were visualized by ECL (Amersham) and quantitated using PhotoImager (Molecular Dynamics). Values for protein levels were given as relative percentage to Ntg sham group after normalization with individual α-tubulin levels for equal loading.

Drug treatments

For the drug treatment, ETA receptor antagonist, ABT-627, was dissolved in 0.25 M NaCO3. Both Ntg and GET-1 mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg ETA receptor antagonist, ABT-627 (a generous gift from Dr. Ruth Wu-Wong), 5 mins after onset of SAH. For the vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist treatment, SR 49059 was dissolved in 10% DMSO. The mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg SR 49059, 5 mins after SAH. The dosage concentration used was similar to the effective dosage concentration used in a previous study [34]. For all the drug tests, vehicle-treated mice were used as controls.

Results

GET-1 mice had a higher death rate than the Ntg mice after SAH

The survival rate of Ntg, and GET-1 mice was 100% and 77%, respectively, 24 hours after SAH. The survival rate of Ntg mice decreased steadily on Day 2 (90%) and Day 3 (80%) after SAH. However, GET-1 mice showed a substantial drop in the survival rate, 61% and 54% on Day 2 and Day 3, respectively. GET-1 mice were more susceptible to SAH damage with a death rate of about 50% three days after SAH (Figure 1A).

Effects of subarachnoid hemorrhage induction in Ntg and GET-1 mice after subarachnoid hemorrhage. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves show the survival data of the Ntg (solid line, n = 10) and the GET-1 (broken line, n = 13) mice after subarachnoid hemorrhage. (B) Line graph shows the cerebral blood flow of Ntg and GET-1 mice during SAH. (C) Histogram comparing the neurological deficit scores for the Ntg (white bar) and GET-1 (black bar) mice after SAH for 3 days. (*P < 0.05, Mann-Whitey test; n = 10 for Ntg and GET-1 mice).

Laser-doppler flowmetry

Upon subarachnoid hemorrhage induction, there was a dramatic and immediate decrease in cerebral perfusion (to < 20% of baseline) in both Ntg and GET-1 mice (Figure 1 B). The relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was recovered gradually to about >80% in the Ntg mice and about 70% in the GET-1 mice after 20 minutes. Ntg mice showed significantly higher rCBF when compared with the GET-1 mice during the reperfusion time points of 10, 12 and 14 minutes (Ntg: 50.6 ± 8.4, 55.9 ± 6.5, 66.5 ± 6.3 vs GET-1: 26.9 ± 3.8, 34.1 ± 4.8, 43.6 ± 6.1, n = 9, *P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney test). In the sham groups, no changes of rCBF were observed in both Ntg and GET-1 mice (~ 100%) and at all time points, the rCBF of sham groups was significantly higher than the SAH-induced group (data not shown).

GET-1 mice exhibited more severe neurological dysfunction than the Ntg mice after SAH

The neurological deficits of the Ntg and GET-1 mice were evaluated for 3 days after SAH. As indicated in the neurological deficit score, the Ntg mice exhibited the greatest neurological dysfunction on Day 1 after SAH (40.0± 7.5; n = 10) and recovered gradually on Day 2 (31.1± 7.6; n = 10) and Day 3 (23.1± 6.4; n = 10). In the GET-1 mice, the neurological dysfunction on Day 1 after SAH was 56.8± 8.1(n = 10) and the mice gradually recovered on Day 2 (51.7.1± 7.0; n = 10) and Day 3 (39.2± 5.3; n = 10). During the whole period of neurological deficit assessment, GET-1 mice showed higher dysfunction compared to Ntg mice after SAH, with a significant difference on Day 2 (*P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 1C).

GET-1 mice were more susceptible to blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown than Ntg mice after SAH

To further understand the role of astrocytic ET-1 in SAH-induced neurological dysfunction in GET-1 mice, the BBB integrity in both Ntg and GET-1 mice was investigated with Evans Blue (EB) extravasation experiment (Figure 2A). At 24 hours after SAH, the amount of EB leakage was increased in NTg and GET-1 mice when compared with their sham groups. Most importantly, a significant elevation of EB leakage was observed in GET-1 brains (Ntg: 2.42 ± 0.54 μg/hemisphere vs GET-1: 5.74 ± 0.87 μg/hemisphere, n = 8, **P < 0.01 by Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 2A), indicating increased BBB permeability and more BBB breakdown in the brains of GET-1 mice after SAH.

GET-1 mice showed more severe brain edema with upregulation of ET-1 and GFAP expressions after subarachnoid hemorrhage. (A) Analysis the integrity of the BBB with the EB extravasation in Ntg and GET-1 brain after SAH. (*P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 4 for the sham groups and n = 8 for the SAH groups). (B) Histogram comparing the water content of the Ntg and GET-1 mice with or without SR 49059 treatment after SAH (*P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 4 for each group of mice). (C) Immunocytochemical analysis of ET-1 expression in Ntg brain after SAH. Representative micrograph shows the expression of ET-1 in the hippocampal region of the Ntg brain after Sham (i) and SAH (ii) (n = 4 for each group). Histogram below shows the quantification results (relative value in percentage) of ET-1 Sham and SAH of Ntg brain sections using software ImageJ. (**P < 0.01, student t-test; n = 4 for each group of mice). (D) Immunocytochemical analysis of GFAP expression after SAH. Representative micrograph shows the localization and expression of GFAP in the astrocytes of the hippocampus of the Ntg and GET-1 brain at (i-iv) low and (v-viii) high magnification (n = 4 for each group). The GFAP signals in the astrocytes at the SAH groups of the Ntg and GET-1 brains is increased, and they have longer processes (arrowheads). Histogram below shows the quantification results (relative value in percentage) of GFAP Sham and SAH of Ntg and GET-1 brain sections using software ImageJ. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 4 for each group of mice).

GET-1 mice accumulated more water in their brains than the Ntg mice after SAH, and SR 49059 significantly reduced the water content in the GET-1 mice after SAH

GET-1 mice brains showed more severe BBB breakdown, suggesting that those mice experienced more severe vasogenic edema after SAH. A significant difference was observed in the cerebral water content between the Ntg and the GET-1 mice (Ntg: 78.0 ± 0.20%; GET-1: 79.60 ± 0.23%; *P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney test) suggesting that the GET-1 mice were more susceptible to SAH-induced cerebral edema (Figure 2B).

A previous study reported that arginine vasopressin (AVP) V2 receptor antagonist ameliorates cytotoxic edema and SAH-induced cerebral edema formation [35]. To investigate whether another subtype of vasopressin receptor is also involved in SAH-induced vasogenic edema development, V1a receptor antagonist, SR 49059, was tested. A significant reduction of cerebral water content was observed in both Ntg and GET-1 mice treated with SR 49059 when compared with their vehicle-treated group (Ntg vehicle-treated: 78.03 ± 0.18%; Ntg SR 49059-treated: 77.24 ± 0.21%, GET-1 vehicle-treated: 79.68 ± 0.20%; GET-1 SR 49059-treated: 78.60 ± 0.21%, *P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 2B). For both genotypes, all mice survived 24 hours after SR 49059 treatment.

Upregulation of endothelin-1 (ET-1) in the wild-type mice brain after SAH

To investigate whether ET-1 is involved in the pathophysiology of SAH, the expression level of ET-1 was examined by the immunocytochemical analysis. After SAH, the Ntg brains showed a significant upregulation of ET-1 expression in the hippocampal region, where astrocytes are highly re-activated under stress conditions, when compared with the sham control. This suggested that astrocytic ET-1 played a role in the pathophysiology of SAH condition (Figure 2C).

Increased glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the GET-1 mice brain after SAH

To further understand the role of over-expressing astrocytic ET-1 in the pathogenesis after SAH, immunocytochemistry was used to determine the expression and cellular location of GFAP.

GFAP is an intermediate filament cytoskeletal protein expressed primarily by astroglia. Increased expression of GFAP represents astroglial activation and gliosis in many neurodegenerative diseases; therefore, GFAP has been used as an indicator of brain injury [36–38]. After SAH, both Ntg and GET-1 brains showed a significant increase in the GFAP expression in the hippocampal region when compared with their sham control. At a higher magnification, GFAP-labeled astrocytes were stained brownish and appeared star-shaped. The GFAP staining in the brain of the GET-1 mice was significantly more intense and widespread in the hippocampal region compared to the Ntg mice. Furthermore, longer astrocytic processes were observed in the GET-1 mice brains (Figure 2D).

GET-1 mice exhibited a more severe vasospasm after SAH

To investigate the role of astrocytic ET-1 on SAH-induced vasospasm, MCAs were isolated and examined from both genotypes after SAH. Vasospasm in the MCA was observed in both Ntg and GET-1 when compared to their sham groups, and the MCA in the brains of the GET-1 mice showed more severe constrictions compared to the Ntg mice (Sham: Ntg 126.2 ± 7.4 μm vs GET-1 132.2 ± 10.4 μm; SAH: Ntg 106.5 ± 2.3 μm vs GET-1 99.7 ± 3.1 μm, n = 5, *P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 3A).

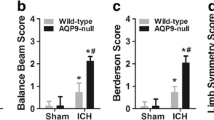

Vasospasm analysis and NOS expressions in MCA after subarachnoid hemorrhage. (A) Representative pictures show the histological analysis of MCA. Vasospasm is observed in both Ntg and GET-1 brain after SAH when compared to that of their sham group (n = 5). Histogram shows the arterial diameter measurement of MCA in Ntg and GET-1 after SAH. (*P < 0.05, Mann-Whitey test; n = 5 for Ntg and GET-1 mice). Expression of NOS in MCA after SAH. Representative photos shows the (B) nNOS, (C) eNOS and (D) p-eNOS expressions of sham and SAH of MCA in Ntg and GET-1 brain. Arrowheads show the expression of nNOS (tunica adventitia) and eNOS/p-eNOS (tunica intima), (n = 4 for each group of mice). Histograms show the quantification results (relative value in percentage) of immunocytochemistry of sham and SAH of Ntg and GET-1 MCA sections. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 4 for each group of mice).

Immunocytochemical studies of NOS expression in MCA

Nitric oxide (NO), also known as an Endothelium-Derived Relaxing Factor, which is generated by vascular endothelium and is one of the important factors that regulates smooth muscle tone [39]. nNOS is produced in the adventitia and eNOS is produced in intima [40], and studies have shown that both neuronal (nNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) depletion underlies vasospasm [39, 41]. ICC was performed to investigate the expression of NOs in GET-1 mice brains after SAH. After SAH, the expression of nNOS in the layer of adventitia (arrows) of MCA was reduced in both genotypes when compared to their sham groups. Significant reduction in nNOS was observed in the MCA of GET-1 mice compared to the Ntg mice after SAH (Figure 3B). Furthermore, both eNOS and p-eNOS expressions were significantly reduced in both of Ntg and GET-1 MCA after SAH compared to their sham groups. Additionally, p-eNOS expression of GET-1 MCA after SAH was significantly reduced when compared to that of Ntg MCA (Figure 3C and D).

GET-1 mice showed an upregulation of PKC-α/phospho-PKC-α expression in the brain after SAH

In SAH, ET-1 induces the development of vasospasm through enhancement of PKC-α activity, and the increased-PKC-α activity inhibits eNOS production [42, 43]. To investigate whether PKC-α mediates astrocytic ET-1 induced downregulation of NOS, Western blot analysis was performed. Significant upregulation of PKC-α and p-PKC-α was observed in the brain of both Ntg and GET-1 mice after SAH when compared to their sham groups (Ntg Sham: 100 ± 3.7% vs Ntg SAH: 119.7 ± 4.6%, P < 0.05; GET-1 Sham: 100.5 ± 3.7% vs GET-1 SAH: 135.8 ± 1.6% P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney test; n = 4). Significant difference was observed between Ntg and GET-1 mice brain after SAH (Ntg SAH; 119.7 ± 4.6% vs GET-1 SAH 135.8 ± 1.6% P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney test; n = 4) (Figure 4).

Western blot analysis of PKC-α and p-PKC-α in Ntg and GET-1 brain after SAH. Representative blots show PKC-α and p-PKC-α expression in the sham and SAH groups of Ntg and GET-1 brain. Histogram below shows the quantification (relative percentage) of the Western blot. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Mann-Whitey test; n = 4 for Ntg and GET-1 mice).

GET-1 MCA showed downregulation of potassium channels after SAH

The vascular tone of the smooth muscle is regulated by the K+ membrance conductance and studies have shown that reduced expression of the potassium channels might contribute to vasospasm after SAH [44, 45]. To investigate the expression of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel in the MCA after SAH, immunocytochemical analysis was performed. Significant downregulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel expression was observed in both Ntg and GET-1 MCA after SAH compared to their sham groups. GET-1 MCA after SAH showed a significant reduction of Ca2+-activated K+ channel expression compared to the Ntg MCA (Figure 5A), suggesting that astrocytic ET-1 mediated-SAH induces a more severe dysfunction of K+ channel that might lead to cerebral vasospasm.

Immunocytochemical analysis of Ca2+-activated K+channel and ET A R expressions in Ntg and GET-1 MCA after SAH. (A) Representative micrograph shows the localization and expression of Ca2+-activated K+ channel in the MCA of the Ntg and GET-1 after SAH. (n = 3 from each group of mice). Histogram shows the quantification results (relative value in percentage) of immunocytochemistry of sham and SAH of Ntg and GET-1 MCA sections. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 3 for each group of mice). (B) Representative micrograph shows the localization and expression of ETAR in the smooth muscle cells (arrows) of MCA in Ntg and GET-1 mice. Histogram shows the quantification results (relative value in percentage) of immunocytochemistry of sham and SAH of Ntg and GET-1 MCA sections. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test; n = 3 for each group of mice). (C) Representative micrograph shows the immunocytochemical expressions of PKC-α and the diameters of MCA after treating with ETAR antagonist ABT-627. Histogram below shows the measurements of MCA diameter. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Mann-Whitey test; n = 3 for Ntg and GET-1 mice).

ETAreceptor antagonist ameliorated vasospasm after SAH

ET-1 is one of the important factors in development of vasospasm after SAH and plays a role in vascular tone of smooth muscle contraction through ETA receptor [46]. ETA receptor is localized in the vascular smooth muscle cells and mediates vascular contraction [47]. When compared to their sham groups, the expression of ETA receptor only slightly increased in the smooth muscle cells (tunica media) (arrows) in both Ntg and GET-1 MCA after SAH (Figure 5B). To determine if ETA receptor plays a role in the development of vasospasm, ABT-627, a competitive ETA receptor anatagonist, was administrated 5 mins after onset of SAH. Treatment with ABT-627 resulted in an improvement in neurological deficits and reduced infarct size after MCAO in GET-1 mice. In Figure 5C, down-regulation of PKC-α was observed in both Ntg and GET-1 MCA after ABT-627 treatment when compared to the vehicle controls. In addition, ABT-627 treatment significantly ameliorated vasospasm in the MCA of both GET-1 and Ntg mice compared to their vehicle controls. ABT-627 treatment resulted in a more promising improvement in GET-1 mice when compared to Ntg mice (Ntg SAH: 114.5 ± 4.9 μm vs Ntg SAH + ABT-627: 133.5 ± 5.1 μm; GET-1 SAH: 104.7 ± 3.1 μm vs GET-1 SAH + ABT-627: 138.6 ± 1.0 μm, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 Mann–Whitney test; n = 3). Administration of ETB receptor anatagonist, BQ788, however, did not show any effect in either genotypes (data not shown).

Discussion

Elevation of ET-1 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid after SAH have been reported in SAH patients [18]. ET-1 is known to be a potent endothelium-derived vasoconstricting agent [48]. In the CNS, ET-1 can be produced by astrocytes, neurons and pituitary cells under normal physiological conditions [12, 14, 49]. ET-1 is also released from endothelial and smooth muscle cells when stimulated by thrombin and oxyhemoglobin [8, 50]. However, to date the source and the release mechanisms of ET-1 are still largely unknown. In order to address whether astrocytic ET-1 plays a role in the development of cerebral edema and vasospasm after SAH, transgenic mice over-expressing ET-1 in astrocytes (GET-1) was used to exaggerate the effects of ET-1 during SAH and delayed ischemia after SAH. The GET-1 mice (from 1 week to 20 weeks old) show higher endothelin-1 mRNA and peptide levels in the brain when compared to Ntg brains. In spite of the increased level of astrocytic ET-1, GET-1 mice appear normal under physiological condition. The cerebrovasculature and the mean artery blood pressure is similar in the GET-1 compared to the Ntg mice, suggesting that the GET-1 mice show no significant difference in the cerebral artery under normal physiological condition [20]. Although GET-1 mice have been shown to have higher endothelin-1 mRNA and peptide levels in the brain when compared to Ntg brains [20], their cerebrovasculatures showed no significant difference to that of Ntg brains. We speculate that the insignificant increased level of ET-1 in GET-1 mice may not cause any exacerbating effects on cerebral vasospasm and edema formation; however, these mice will be more susceptible to these pathophysiological processes under stress conditions, such as SAH when astrocytic ET-1 level will be increased substantially.

Vasopressin levels increase in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid after SAH, suggesting that the antidiuretic hormone plays a critical role in edema development [51]. SR 49059 is considered to be the most potent and selective non-peptide V1a receptor antagonist in both animals and human [52, 53]. Recently, SR 49059 was shown to reduce intracerebral hemorrhagic brain injury-induced cerebral edema in mice [54]. In the present study, arterial puncture technique was used to induce subarachnoid hemorrhage, and GET-1 mice developed more severe brain damage and edema after this procedure. SR 49059 was administrated intraperitoneally to the NTg and GET-1 mice to evaluate the effect of vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist in the edema formation after SAH. The results showed that SR 49059 significantly reduced brain water content in both Ntg and GET-1 mice 24 hours after SAH, which is in agreement with a previous study [55] despite using a different type of hemorrhagic stroke model and paradigm. Collectively, these data suggest that SR 49059 is a promising drug in treating hemorrhagic brain edema and provide a strong rationale to investigate the drug in clinical settings.

Although many studies have reported that ET-1 levels are increased in plasma and CSF during ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [56, 57], it is still unclear whether the production and release of ET-1 is the primary response of the brain cells (astrocytes, endothelial cells, neurons) to the stroke, or the secondary response in which activation of the sympathoadrenal system increases the plasma catecholamine and vasopressin levels [58], which stimulates the release of ET-1 from the peripheral organs. In the present study, over-expression of astrocytic ET-1 in GET-1 mice resulted in a more severe brain damage and vasospasm, suggesting that astrocytes may be one of the major sources of ET-1 production and release under pathological conditions. Previous in vitro data suggested that the SAH-induced hypoxia-ischemia in astrocytes accounts for the ET-1 release into the subarachnoid space [56]. The present report provides the first documentation for the significance of astrocytic ET-1 in haemorrhagic stroke in an animal model. Our data demonstrate that overexpression of astrocytic ET-1 excerbates several pathophysiological processes after SAH, and this could be a contributing factor to these processes together with the physiological levels of astrocytic ET-1, however, we could not directly conclude that this is the case. Further studies in animals, such as with targeted deletion of astrocytic ET-1, will be required before drawing the conclusion.

In agreement with other studies, we demonstrate that astrocytic ET-1 also induces vasospasm with a concurrent elevation of PKC-α protein expression and activation [43, 59, 60]. ET-1 regulates the vascular tone of the cerebral blood vessels through its receptor subtypes, ETA and ETB. ETB receptors are known to mediate vasodilation upon localization to the endothelial cells of blood vessels. A recent study shows that the expression of ETB receptors is regulated by initial cerebral blood flow through the MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway [61]. ETA receptors are mainly found in smooth muscle cells and are involved in vasoconstriction; therefore, they are crucial in cerebral vasospasm [62]. In the present study, immunocytochemical analysis of ETA receptor expression in MCA showed an insignificant change in both Ntg and GET-1 after SAH, which is in agreement with the previous finding that the expression of smooth-muscle ETA receptors and their mRNA level is unchanged or slightly increased in the cerebral arteries after SAH [63, 64]. It is demonstrated that an increased coupling of the smooth muscle ETA receptor with the second cascade probably contributes to the development of cerebral vasospasm [64]. ETA receptor antagonists have been used in numerous studies in alleviating SAH-induced cerebral vasospasm [65–67]. However, other studies have also reported that ETA receptor antagonists have the potential adverse effects such as hypotension and pneumonia. Moreover, there are no significant differences in mortality or improving outcomes in the phase 3 clinical trials investigating ETA receptor antagonists as a therapeutic strategy for vasospasm [68–71]. However, ETA receptor antagonists, such as clazosentan, have been used in alleviating SAH-induced cerebral vasospasm [72]. In a clinical study, only high doses of clazosentan resulted in a significantly reduced vasospasm-related morbidity or all-cause mortality within 6 weeks post SAH, but not at longer time points [69], suggesting that ETA receptor antagonist could be used for treating vasospasm. However, the interference by other drugs taken by the patients during the clinical study may reduce the efficiency of the clazosentan at a later time point. In the current study, ETA receptor antagonist ABT-627 effectively attenuated SAH-induced vasospasm in both Ntg and GET-1 mice, and suggested that pathways elicited by astrocytic ET-1 through ETA receptor, but not ETB receptor, are involved in SAH-induced vasospasm. ABT-627 is reported to greatly improve neurological deficits and reduce infarct size in mice after ischemic stroke, suggesting that the drug could normalize the vasoconstriction effect of ET-1 [28], as shown in the present study. Although a few ETA receptor antagonists have been shown to have adverse effects in the SAH patients, we cannot rule out the possibility that there are pharmacological differences among ETA receptor antagonists as well as testing conducted under non-optimized conditions. Here we report another possible ETA receptor antagonist candidate, ABT-627, which may be an alternative therapeutic drug for treating SAH-induced vasospasm.

ET-1 stimulates the ETB receptor and increases NO production [73]. NO is suggested to reverse the effects of the ET-1-induced vasoconstriction, by negative feedback and reducing the level of ET-1 [73, 74]. Diminished production of NO and increased release of ET-1, therefore, are suggested to be the vital consequences of vasospasm in SAH [75]. It is reported that endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression as well as NO production are impaired by the elevated ET-1 level through a PKC-dependent pathway [42]. Since nitric oxide induces vascular relaxation by inhibiting PKC activity, the reduced NO production after SAH, therefore, enhances the PKC-dependent vasoconstriction [76]. Also, elevated level of ET-1 activates ETA receptor and decreases the vascular sensitivity to NO by a PKC-independent pathway [77]. Down-regulation of PKC-α was observed in both Ntg and GET-1 MCA after ETA receptor antagonist ABT-627 treatment (Figure 5C), suggesting that astrocytic ET-1 induced vasospasm is also mediated through ETA receptor and PKC. These data collectively provide a strong rationale to investigate ABT-627 as a therapeutic drug to treat SAH-induced vasospasm.

K+ channels are important in regulating the membrane potential of arterial smooth muscle. Large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel is one of the channels that is found in the arterial smooth muscle and contributes to the resting membrane potential [45]. Recently, the function and expression of ion channels, particularly the Ca2+-activated K+ channels, have been investigated in SAH-induced vasospasm. In the present study, the expression of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in MCA was largely reduced after SAH in both Ntg and GET-1 mice, which is in agreement with others findings that elevated PKC activity after SAH causes dysfunction in K+ channel activity and expression [78, 79].

Here we propose the possible mechanism of the astrocytic ET-1 mediated cerebral vasospasm after SAH (Figure 6). The astrocytic ET-1 induces cerebral vasospasm through the ETA receptor, which leads to an upregulation of PKC-α.

Proposed mechanism of astrocytic ET-1 mediated cerebral vasospasm after SAH. GET-1 mice with over-expressed in ET-1 showed more severe neurological deficits and vasospasm after SAH. Increased astrocytic ET-1 during SAH induces cerebral vasospasm through the ETA receptor and mediated by PKC-α, which leads to dynfunction in the K+ channels. Administration of ETA receptor antagonist ABT-627 ameliorates the SAH-induced vasospasm. The impairment of NO system also exaggerates the vasospasm effect. Astrocytic ET-1 leads to more severe cerebral edema and BBB breakdown that further contributes to cerebral vasoconstriction. Vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist, SR 49059, significantly reduced the SAH-induced edema, suggesting that astrocytic ET-1 induces edema in SAH through vasopressin V1a receptor.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to elucidate the role of astrocytic ET-1 in vasogenic edema formation and vasospasm development in SAH-induced brain injured mice. Both the vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist, SR 49059, and ETA receptor inhibitor, ABT-627 significantly ameliorated the astrocytic ET-1 induced complications after SAH. These potential therapeutic drugs could be used in future for treating SAH patients.

References

Claassen J, Carhuapoma JR, Kreiter KT, Du EY, Connolly ES, Mayer SA: Global cerebral edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: frequency, predictors, and impact on outcome. Stroke. 2002, 33 (5): 1225-1232. 10.1161/01.STR.0000015624.29071.1F.

Macdonald RL: Pathophysiology and molecular genetics of vasospasm. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2001, 77: 7-11.

Molnar AH, Varga C, Berko A, Rojik I, Parducz A, Laszlo F, Laszlo FA: Inhibitory effect of vasopressin receptor antagonist OPC-31260 on experimental brain oedema induced by global cerebral ischaemia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008, 150 (3): 265-271. 10.1007/s00701-007-1400-1.

Liu X, Nakayama S, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Ottersen OP, Bhardwaj A: Arginine-vasopressin V1 but not V2 receptor antagonism modulates infarct volume, brain water content, and aquaporin-4 expression following experimental stroke. Neurocrit Care. 2010, 12 (1): 124-131. 10.1007/s12028-009-9277-x.

Kleindienst A, Fazzina G, Dunbar JG, Glisson R, Marmarou A: Protective effect of the V1a receptor antagonist SR 49059 on brain edema formation following middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006, 96: 303-306. 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_65.

Sano K, Asano T, Tanishima T, Sasaki T: Lipid peroxidation as a cause of cerebral vasospasm. Neurol Res. 1980, 2 (3–4): 253-272.

Kanamaru K, Waga S, Kojima T, Fujimoto K, Niwa S: Endothelium-dependent relaxation of canine basilar arteries. Part 2: Inhibition by hemoglobin and cerebrospinal fluid from patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1987, 18 (5): 938-943. 10.1161/01.STR.18.5.938.

Cocks TM, Malta E, King SJ, Woods RL, Angus JA: Oxyhaemoglobin increases the production of endothelin-1 by endothelial cells in culture. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991, 196 (2): 177-182. 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90425-P.

Macdonald RL, Weir BK: A review of hemoglobin and the pathogenesis of cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 1991, 22 (8): 971-982. 10.1161/01.STR.22.8.971.

Asano T, Ikegaki I, Suzuki Y, Satoh S, Shibuya M: Endothelin and the production of cerebral vasospasm in dogs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989, 159 (3): 1345-1351. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92258-4.

Mima T, Yanagisawa M, Shigeno T, Saito A, Goto K, Takakura K, Masaki T: Endothelin acts in feline and canine cerebral arteries from the adventitial side. Stroke. 1989, 20 (11): 1553-1556. 10.1161/01.STR.20.11.1553.

Giaid A, Gibson SJ, Ibrahim BN, Legon S, Bloom SR, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Varndell IM, Polak JM: Endothelin 1, an endothelium-derived peptide, is expressed in neurons of the human spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989, 86 (19): 7634-7638. 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7634.

Lee ME, de la Monte SM, Ng SC, Bloch KD, Quertermous T: Expression of the potent vasoconstrictor endothelin in the human central nervous system. J Clin Invest. 1990, 86 (1): 141-147. 10.1172/JCI114677.

MacCumber MW, Ross CA, Snyder SH: Endothelin in brain: receptors, mitogenesis, and biosynthesis in glial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87 (6): 2359-2363. 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2359.

Fassbender K, Hodapp B, Rossol S, Bertsch T, Schmeck J, Schutt S, Fritzinger M, Horn P, Vajkoczy P, Wendel-Wellner M, et al: Endothelin-1 in subarachnoid hemorrhage: An acute-phase reactant produced by cerebrospinal fluid leukocytes. Stroke. 2000, 31 (12): 2971-2975. 10.1161/01.STR.31.12.2971.

Kasuya H, Weir BK, White DM, Stefansson K: Mechanism of oxyhemoglobin-induced release of endothelin-1 from cultured vascular endothelial cells and smooth-muscle cells. J Neurosurg. 1993, 79 (6): 892-898. 10.3171/jns.1993.79.6.0892.

Ehrenreich H, Lange M, Near KA, Anneser F, Schoeller LA, Schmid R, Winkler PA, Kehrl JH, Schmiedek P, Goebel FD: Long term monitoring of immunoreactive endothelin-1 and endothelin-3 in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid, plasma, and 24-h urine of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Res Exp Med (Berl). 1992, 192 (4): 257-268.

Fujimori A, Yanagisawa M, Saito A, Goto K, Masaki T, Mima T, Takakura K, Shigeno T: Endothelin in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 1990, 336 (8715): 633.

Suzuki R, Masaoka H, Hirata Y, Marumo F, Isotani E, Hirakawa K: The role of endothelin-1 in the origin of cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1992, 77 (1): 96-100. 10.3171/jns.1992.77.1.0096.

Lo AC, Chen AY, Hung VK, Yaw LP, Fung MK, Ho MC, Tsang MC, Chung SS, Chung SK: Endothelin-1 overexpression leads to further water accumulation and brain edema after middle cerebral artery occlusion via aquaporin 4 expression in astrocytic end-feet. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005, 25 (8): 998-1011. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600108.

Yeung PK, Lo AC, Leung JW, Chung SS, Chung SK: Targeted overexpression of endothelin-1 in astrocytes leads to more severe cytotoxic brain edema and higher mortality. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29 (12): 1891-1902. 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.175.

Bederson JB, Germano IM, Guarino L: Cortical blood flow and cerebral perfusion pressure in a new noncraniotomy model of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat. Stroke. 1995, 26 (6): 1086-1091. 10.1161/01.STR.26.6.1086. discussion 1091–1082

Huang Z, Huang PL, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA: Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science. 1994, 265 (5180): 1883-1885. 10.1126/science.7522345.

Carrillo P, Takasu A, Safar P, Tisherman S, Stezoski SW, Stolz G, Dixon CE, Radovsky A: Prolonged severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in rats does not cause subtle brain damage. J Trauma. 1998, 45 (2): 239-248. 10.1097/00005373-199808000-00007. discussion 248–239

Kamii H, Kato I, Kinouchi H, Chan PH, Epstein CJ, Akabane A, Okamoto H, Yoshimoto T: Amelioration of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage in transgenic mice overexpressing CuZn-superoxide dismutase. Stroke. 1999, 30 (4): 867-871. 10.1161/01.STR.30.4.867. discussion 872

Mesis RG, Wang H, Lombard FW, Yates R, Vitek MP, Borel CO, Warner DS, Laskowitz DT: Dissociation between vasospasm and functional improvement in a murine model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurg Focus. 2006, 21 (3): E4.

McGirt MJ, Lynch JR, Parra A, Sheng H, Pearlstein RD, Laskowitz DT, Pelligrino DA, Warner DS: Simvastatin increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase and ameliorates cerebral vasospasm resulting from subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002, 33 (12): 2950-2956. 10.1161/01.STR.0000038986.68044.39.

Ostrowski RP, Colohan AR, Zhang JH: Mechanisms of hyperbaric oxygen-induced neuroprotection in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005, 25 (5): 554-571. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600048.

Altay O, Suzuki H, Hasegawa Y, Caner B, Krafft PR, Fujii M, Tang J, Zhang JH: Isoflurane attenuates blood–brain barrier disruption in ipsilateral hemisphere after subarachnoid hemorrhage in mice. Stroke. 2012, 43 (9): 2513-2516. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.661728.

Yatsushige H, Ostrowski RP, Tsubokawa T, Colohan A, Zhang JH: Role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosci Res. 2007, 85 (7): 1436-1448. 10.1002/jnr.21281.

Sabri M, Jeon H, Ai J, Tariq A, Shang X, Chen G, Macdonald RL: Anterior circulation mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2009, 1295: 179-185.

Mak KM, Lo AC, Lam AK, Yeung PK, Ko BC, Chung SS, Chung SK: Nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 deficiency increases the severity of neuronal cell death in ischemic injury. Neurosignals. 2012, 20 (4): 237-251.

Lin EY, Li JF, Gnatovskiy L, Deng Y, Zhu L, Grzesik DA, Qian H, Xue XN, Pollard JW: Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66 (23): 11238-11246. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1278.

Shuaib A, Xu Wang C, Yang T, Noor R: Effects of nonpeptide V(1) vasopressin receptor antagonist SR-49059 on infarction volume and recovery of function in a focal embolic stroke model. Stroke. 2002, 33 (12): 3033-3037. 10.1161/01.STR.0000039405.31526.06.

Laszlo FA, Varga C, Nakamura S: Vasopressin receptor antagonist OPC-31260 prevents cerebral oedema after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999, 364 (2–3): 115-122.

Liao CW, Fan CK, Kao TC, Ji DD, Su KE, Lin YH, Cho WL: Brain injury-associated biomarkers of TGF-beta1, S100B, GFAP, NF-L, tTG, AbetaPP, and tau were concomitantly enhanced and the UPS was impaired during acute brain injury caused by Toxocara canis in mice. BMC Infect Dis. 2008, 8: 84-10.1186/1471-2334-8-84.

Pekny M, Pekna M: Astrocyte intermediate filaments in CNS pathologies and regeneration. J Pathol. 2004, 204 (4): 428-437. 10.1002/path.1645.

Pekny M, Wilhelmsson U, Bogestal YR, Pekna M: The role of astrocytes and complement system in neural plasticity. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007, 82: 95-111.

Ignarro LJ: Nitric oxide as a unique signaling molecule in the vascular system: a historical overview. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002, 53 (4 Pt 1): 503-514.

Pluta RM: Dysfunction of nitric oxide synthases as a cause and therapeutic target in delayed cerebral vasospasm after SAH. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008, 104: 139-147. 10.1007/978-3-211-75718-5_28.

Pluta RM, Thompson BG, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Boock RJ, Oldfield EH: Loss of nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg. 1996, 84 (4): 648-654. 10.3171/jns.1996.84.4.0648.

Ramzy D, Rao V, Tumiati LC, Xu N, Sheshgiri R, Miriuka S, Delgado DH, Ross HJ: Elevated endothelin-1 levels impair nitric oxide homeostasis through a PKC-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2006, 114 (1 Suppl): I319-I326.

Nishizawa S, Chen D, Yokoyama T, Yokota N, Otha S: Endothelin-1 initiates the development of vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage through protein kinase C activation, but does not contribute to prolonged vasospasm. Acta Neurochir. 2000, 142 (12): 1409-1415. 10.1007/s007010070013.

Aihara Y, Jahromi BS, Yassari R, Nikitina E, Agbaje-Williams M, Macdonald RL: Molecular profile of vascular ion channels after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004, 24 (1): 75-83.

Standen NB, Quayle JM: K + channel modulation in arterial smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998, 164 (4): 549-557. 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00433.x.

Zimmermann M, Seifert V: Endothelin and subarachnoid hemorrhage: an overview. Neurosurgery. 1998, 43 (4): 863-875. 10.1097/00006123-199810000-00083. discussion 875–866

Zimmermann M, Seifert V: Endothelin receptor antagonists and cerebral vasospasm. Clin Auton Res. 2004, 14 (3): 143-145.

Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T: A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988, 332 (6163): 411-415. 10.1038/332411a0.

Yoshizawa T, Shinmi O, Giaid A, Yanagisawa M, Gibson SJ, Kimura S, Uchiyama Y, Polak JM, Masaki T, Kanazawa I: Endothelin: a novel peptide in the posterior pituitary system. Science. 1990, 247 (4941): 462-464. 10.1126/science.2405487.

Ehrenreich H, Costa T, Clouse KA, Pluta RM, Ogino Y, Coligan JE, Burd PR: Thrombin is a regulator of astrocytic endothelin-1. Brain Res. 1993, 600 (2): 201-207. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91374-2.

Laszlo FA, Varga C, Doczi T: Cerebral oedema after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Pathogenetic significance of vasopressin. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995, 133 (3–4): 122-133.

Serradeil-Le Gal C, Wagnon J, Garcia C, Lacour C, Guiraudou P, Christophe B, Villanova G, Nisato D, Maffrand JP, Le Fur G, et al: Biochemical and pharmacological properties of SR 49059, a new, potent, nonpeptide antagonist of rat and human vasopressin V1a receptors. J Clin Invest. 1993, 92 (1): 224-231. 10.1172/JCI116554.

Thibonnier M, Kilani A, Rahman M, DiBlasi TP, Warner K, Smith MC, Leenhardt AF, Brouard R: Effects of the nonpeptide V(1) vasopressin receptor antagonist SR 49059 in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999, 34 (6): 1293-1300. 10.1161/01.HYP.34.6.1293.

Manaenko A, Fathali N, Khatibi NH, Lekic T, Hasegawa Y, Martin R, Tang J, Zhang JH: Arginine-vasopressin V1a receptor inhibition improves neurologic outcomes following an intracerebral hemorrhagic brain injury. Neurochem Int. 2011, 58 (4): 542-548. 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.01.018.

Manaenko A, Fathali N, Khatibi NH, Lekic T, Shum KJ, Martin R, Zhang JH, Tang J: Post-treatment with SR 49059 improves outcomes following an intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in mice. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011, 111: 191-196. 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_32.

Pluta RM, Boock RJ, Afshar JK, Clouse K, Bacic M, Ehrenreich H, Oldfield EH: Source and cause of endothelin-1 release into cerebrospinal fluid after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1997, 87 (2): 287-293. 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0287.

Bian LG, Zhang TX, Zhao WG, Shen JK, Yang GY: Increased endothelin-1 in the rabbit model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neurosci Lett. 1994, 174 (1): 47-50. 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90115-5.

Matsumura K, Abe I, Tsuchihashi T, Tominaga M, Kobayashi K, Fujishima M: Central effect of endothelin on neurohormonal responses in conscious rabbits. Hypertension. 1991, 17 (6 Pt 2): 1192-1196.

Nishizawa S, Obara K, Koide M, Nakayama K, Ohta S, Yokoyama T: Attenuation of canine cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage by protein kinase C inhibitors despite augmented phosphorylation of myosin light chain. J Vasc Res. 2003, 40 (2): 169-178. 10.1159/000070714.

Yang G, Li T, Xu J, Liu L: PKC plays an important mediated effect in arginine vasopressin induced restoration of vascular responsiveness and calcium sensitization following hemorrhagic shock in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010, 628 (1–3): 148-154.

Povlsen GK, Johansson SE, Larsen CC, Samraj AK, Edvinsson L: Early events triggering delayed vasoconstrictor receptor upregulation and cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. BMC Neurosci. 2013, 14 (1): 34-10.1186/1471-2202-14-34.

Chow M, Dumont AS, Kassell NF: Endothelin receptor antagonists and cerebral vasospasm: an update. Neurosurgery. 2002, 51 (6): 1333-1341. discussion 1342

Hansen-Schwartz J, Ansar S, Edvinsson L: Cerebral vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage–role of changes in vascular receptor phenotype. Front Biosci. 2008, 13: 2160-2164. 10.2741/2831.

Vatter H, Konczalla J, Weidauer S, Preibisch C, Zimmermann M, Raabe A, Seifert V: Effect of delayed cerebral vasospasm on cerebrovascular endothelin A receptor expression and function. J Neurosurg. 2007, 107 (1): 121-127. 10.3171/JNS-07/07/0121.

Clozel M, Watanabe H: BQ-123, a peptidic endothelin ETA receptor antagonist, prevents the early cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage after intracisternal but not intravenous injection. Life Sci. 1993, 52 (9): 825-834. 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90081-D.

Kita T, Kubo K, Hiramatsu K, Sakaki T, Yonetani Y, Sato S, Fujimoto M, Nakashima T: Profiles of an intravenously available endothelin A-receptor antagonist, S-0139, for preventing cerebral vasospasm in a canine two-hemorrhage model. Life Sci. 1998, 63 (4): 305-315. 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00274-4.

Zuccarello M, Lewis AI, Rapoport RM: Endothelin ETA and ETB receptors in subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994, 259 (1): R1-R2. 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90167-8.

Kramer A, Fletcher J: Do endothelin-receptor antagonists prevent delayed neurological deficits and poor outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage?: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009, 40 (10): 3403-3406. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.560243.

Macdonald RL, Higashida RT, Keller E, Mayer SA, Molyneux A, Raabe A, Vajkoczy P, Wanke I, Bach D, Frey A, et al: Clazosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage undergoing surgical clipping: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (CONSCIOUS-2). Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10 (7): 618-625. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70108-9.

Guo J, Shi Z, Yang K, Tian JH, Jiang L: Endothelin receptor antagonists for subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 9: CD008354.

Zemke D, Farooq MU, Mohammed Yahia A, Majid A: Delayed ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: result of vasospasm alone or a broader vasculopathy?. Vasc Med. 2007, 12 (3): 243-249. 10.1177/1358863X07081316.

Vatter H, Konczalla J, Weidauer S, Preibisch C, Raabe A, Zimmermann M, Seifert V: Characterization of the endothelin-B receptor expression and vasomotor function during experimental cerebral vasospasm. Neurosurgery. 2007, 60 (6): 1100-1108. discussion 1108–1109

Pluta RM: Delayed cerebral vasospasm and nitric oxide: review, new hypothesis, and proposed treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2005, 105 (1): 23-56. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.002.

Thomas JE, Nemirovsky A, Zelman V, Giannotta SL: Rapid reversal of endothelin-1-induced cerebral vasoconstriction by intrathecal administration of nitric oxide donors. Neurosurgery. 1997, 40 (6): 1245-1249. 10.1097/00006123-199706000-00026.

Rubanyi GM, Polokoff MA: Endothelins: molecular biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology. Pharmacol Rev. 1994, 46 (3): 325-415.

Nishizawa S, Yokota N, Yokoyama T, Uemura K: Obligatory roles of protein kinase C and nitric oxide in the regulation of cerebral vascular tone: an implication of a pathogenesis of vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998, 140 (10): 1063-1068. 10.1007/s007010050215.

Gilbert P, Tremblay J, Thorin E: Endothelium-derived endothelin-1 reduces cerebral artery sensitivity to nitric oxide by a protein kinase C-independent pathway. Stroke. 2001, 32 (10): 2351-2355. 10.1161/hs1001.096007.

Jahromi BS, Aihara Y, Ai J, Zhang ZD, Weyer G, Nikitina E, Yassari R, Houamed KM, Macdonald RL: Temporal profile of potassium channel dysfunction in cerebrovascular smooth muscle after experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neurosci Lett. 2008, 440 (1): 81-86. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.015.

Ishiguro M, Morielli AD, Zvarova K, Tranmer BI, Penar PL, Wellman GC: Oxyhemoglobin-induced suppression of voltage-dependent K + channels in cerebral arteries by enhanced tyrosine kinase activity. Circ Res. 2006, 99 (11): 1252-1260. 10.1161/01.RES.0000250821.32324.e1.

Acknowledgement

This study was partly supported by the RGC grant to Prof. S.K. Chung and the Area of Excellence from University Grants Council of Hong Kong on “Molecular Neuroscience: Basic Research and Drug Discovery” (AoE/B-15/01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PKKY performed the majority of the experimental work, designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. JS, SSMC and SKC conceived the idea, designed experiments and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeung, P.K., Shen, J., Chung, S.S. et al. Targeted over-expression of endothelin-1 in astrocytes leads to more severe brain damage and vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. BMC Neurosci 14, 131 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-14-131

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-14-131