Abstract

Background

SRY is the pivotal gene initiating male sex determination in most mammals, but how its expression is regulated is still not understood. In this study we derived novel SRY 5' flanking genomic sequence data from bovine and caprine genomic BAC clones.

Results

We identified four intervals of high homology upstream of SRY by comparison of human, bovine, pig, goat and mouse genomic sequences. These conserved regions contain putative binding sites for a large number of known transcription factor families, including several that have been implicated previously in sex determination and early gonadal development.

Conclusion

Our results reveal potentially important SRY regulatory elements, mutations in which might underlie cases of idiopathic human XY sex reversal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sex in mammals normally correlates with the presence or absence of the Y chromosome. Male sex determination in almost all mammals is directly caused by the correct expression and function of a single Y-linked gene, SRY[1–4]. SRY activity in males causes the bipotential gonad, the genital ridge, to set off on the path to becoming a testis. If the fetal genital ridge does not express SRY, ovary development is initiated instead. A majority of gonadal dysgenesis cases cannot be attributed to mutations within or immediately 5' of SRY, or to any other gene known to have a role in sex determination. We hypothesise that this is because SRY's regulatory regions are uncharted, therefore providing no means to check specific areas for mutation.

SRY carries out a similar function in all mammals in which it is present, but displays a high degree of variability between species. This situation is thought to result from the location of SRY on the Y chromosome, exposing it to a higher rate of mutation compared to autosomal genes, thereby leading to DNA degradation and even loss [5]. The region of SRY best conserved between species is the high mobility group (HMG) box, which confers the encoded protein its transcription factor role by allowing it to bind and bend DNA [6, 7]. Outside the HMG box, SRY is very poorly conserved between species. This lack of conservation has made it difficult to define functional motifs required for the role of SRY protein in directing male sex determination.

The regulation of SRY is under tight control to ensure its expression at the right time, place and level necessary to initiate male sex determination. In mice, delayed onset of Sry expression, or reduced levels of Sry expression, is known to cause full or partial XY sex reversal [8–10]. Therefore, an understanding of how SRY expression is regulated is an important part of the overall picture of its functions in male sex determination and of how disturbances in function can lead to disorders of sex development.

As with the SRY coding region, sequences beyond the transcription unit of SRY are very poorly conserved between species, a situation that has contributed to an almost total lack of understanding of how the expression of this gene is regulated. Comparative genomics is normally a powerful tool for identifying biologically important gene regulatory regions, based on the conservation of functional regulatory modules being under selective pressure during evolution [11–13], but this method has shown only limited success in studies of SRY to date. Although mice are most useful for a range of developmental and functional genetic studies, their utility in comparative genomics is limited by their unusually high rate of sequence drift, thought to be linked to their short generation time [14].

Progress in identifying potential gene regulatory motifs through comparative genomics relies on the availability of genome sequences from a range of non-murine mammals. A study analysing non-coding sequences in 39 bovine, human and mouse gene orthologues revealed 73 putative regulatory intervals conserved between bovine and human genes, only 13 of which were also conserved in mice [15]. Further comparative genomic analysis of these regions showed that the homology to human is highest in bovine, and weakest in the mouse. Other studies also point to an excellent conservation of bovine and human sequences in the promoter region of genes such as Oct4, but relatively poor conservation of the corresponding mouse sequences [16].

In the present study we generated novel bovine and caprine SRY 5' sequence data in order to conduct comparative genomic analysis of 5' sequences from human, bull, pig, goat and mouse Sry. In this way we identified four novel sequence intervals that may be important for the correct regulation of SRY expression and therefore for correct function of SRY in mammalian sex determination. The identification of these candidate regulatory regions provides a focus for efforts to discover new mutations associated with human idiopathic XY sex reversal.

Results

Generation of novel Sry genomic flanking sequence from bovine and caprine BACs

In order to provide new tools for comparative genomic analysis of potential SRY 5' regulatory sequences, we first generated novel flanking sequence from the bovine and caprine SRY genes. The BAC clone RP42-95D10 containing bovine SRY [17] was found by Southern blotting and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to contain a 15 kb Eco R1 fragment harbouring SRY (data not shown). This fragment was subcloned, and sequenced to five times coverage [GenBank EU581861].

Alignment of the bovine sequence with published human [EMBL: NT_011896.9 nucleotides 5177–21272] and mouse [EMBL: NT_078925.6 nucleotides 1917040–1934040] SRY 5' sequence allowed the preliminary identification of several potentially conserved sequence blocks. We generated corresponding fragments of the goat SRY 5' region by PCR using as template a goat BAC clone containing SRY and known to cause female to male sex reversal in mice [18]. These fragments were sequenced, aligned, and appended to existing goat SRY sequence where possible, and used for further analysis [Genbank EU581862, EU581863, and EU581864].

Comparative genomic sequence analysis

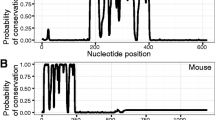

We next used the novel 15 kb of bovine SRY 5' sequence as a reference point for comparative genomic studies. VISTA alignment of the bovine sequence with human, porcine (4.6 kb) [19], caprine (individual regions described above), and mouse (17 kb), revealed four sequence blocks of significant homology (Figure 1). These blocks (A, B, C and D) from human, caprine and porcine SRY displayed at least 50% nucleotide identity to bovine sequence by VISTA analysis using 100 bp windows. The four conserved blocks were separated by non-conserved sequence, the length of which varied between species (Figure 2). In the goat no intervening sequences were detected between region C and D. The main features of each conserved block are as follows:

Homology of human, caprine, porcine and mouse SRY 5' sequences to bovine SRY. Pink shading indicates 70% or higher homologies calculated over 100 bp. Peaks of homology are labelled Region A to D above the graph. Repetitive elements (LINEs and SINEs) are indicated in green, and the SRY coding region in blue. Grey line below each graph shows the extent of sequence used.

Region A (480 bp) lies about 8.3 kb upstream of the start of transcription in bovine SRY (5.6 kb in human; Figure 2). It showed more than 70% conservation in 100 bp windows between bovine, human and caprine sequence over a large proportion of its length using VISTA (Figure 1, pink shading). ClustalW showed overall homology between the three species as 63 – 87% (Figure 3).

Region B (1.5 kb) begins 6.7 kb 5' of the bovine SRY start of transcription (5 kb in human; Figure 2). Bovine/human homology, in 100 bp windows of this region, was above 70%, limited to two short sequence intervals (Figure 1). This high homology between bovine and caprine, and moderate homology between bovine and human sequences, was reflected in overall ClustalW homology analysis of these regions (Figure 3). As in region A, homology of mouse sequence was minimal in this region. The available 4.6 kb of porcine genomic sequence stopped partway through this region, but aligned well with bovine sequence (Figure 1).

Region C (1 kb) was found 3.9 kb upstream on the bovine sequence (3.6 kb in human; Figure 2). This was the least conserved area between bovine and human, not reaching 70% in any 100 bp window using the VISTA browser (Figure 1), and only 19% overall by ClustalW (Figure 3). Caprine sequence showed high homology to bovine in this region, porcine intermediate, and mouse negligible (Figures 1, 3).

Region D was found immediately upstream of bovine, human and caprine SRY, and so represents the proximal promoter region in these species (1.9, 1.5 and 1.9 kb respectively). This region showed strong to moderate conservation across all species except mouse (Figure 1, 3). Conservation between bovine and human sequences was stronger in this region than other regions (Figure 3).

No additional regions of homology were detected distal to region A within the 15 kb of bovine sequence used as anchor, when compared with 17 kb of human and 16 kb of mouse sequence.

Conserved transcription factor binding sites

We next searched for potential transcription factor binding sites in conserved regions A-D in order to evaluate the possible significance of these regions for SRY regulation. In silico DiAlignTF analysis revealed 210 conserved, canonical transcription factor binding sites across the four regions, representing 38 transcription factor families (Table 1 and 2, Figure 4 and additional file 1). None of the transcription factor binding sites were shown as conserved in the mouse using DiAlignTF, although some nucleotide conservation was detectable when viewed by eye (Additional file 1). To allow us to add levels of significance to the putative sites they were grouped according to their occurrence patterns in the sequences (Table 1): most frequent (total number of times represented in the four regions), most common (number of regions containing each type of site) and level of conservation (number of species containing the site) among the four species examined other than mice. In addition, the matrix similarity score for each site (that is, the similarity of each putative site to the canonical binding site for the relevant transcription factor) is shown in Table 3, as further indication of the likely relevance of each putative binding site.

Conserved transcription factor binding sites in each region of homology. Black text indicates conservation between 3 species of which one is human, grey text indicates 3-species conservation without human, and red text indicates conservation between 4 species (human, bovine, porcine and caprine). An example of the highly conserved area of region D is shown as a sequence alignment with conserved transcription factor binding sites boxed or shaded.

The most frequently occurring transcription factor binding sites were those of BRNF and OCT1, which were represented in regions C and D a total of six times. PARF and FKHD binding sites were the next most frequent, represented four times between regions C and D. The HOXF family member binding sites were the most common, found in all of the regions and, in the case of region C, the site was conserved across four species. Eight transcription factor binding sites (HOXF, FKHD, SRFF, LHXF, CDXF repeated twice in the same region, MYT1, PLZF, and NFκB) were conserved across four species, and therefore displayed the highest level of conservation. With the exception of HOXF and LHXF (found in region C), all of these transcription factor binding sites at this four-way conservation level were found to localise to region D (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Region A showed nine areas of conserved transcription factor binding sites, the most common being GATA, occurring twice. All of the sites were conserved between bovine, goat and human. Transcription factor family members unique to Region A were EVI1, TBPF, HOXC, GFI1, PITI, and OCTP (Table 1, Figure 4).

Region B contained the fewest transcription factor binding sites of all the regions. Sites unique to this region were RORA, HAML and RBPF (Table 1, Figure 4).

Region C contained 17 transcription factor binding site family members, with three repeated twice (BRNF, OCT1 and ETSF). Although there appeared to be many conserved transcription factor binding sites, not all were present in the human sequence. Transcription factor binding sites that were conserved in humans are HOXF, ETSF, LHXF and GZF1, all unique to this region with the exception of HOXF (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Region D contained by far the largest number of transcription factor binding sites, with almost 50% of the total found. The majority showed conservation in the human sequence, and six sites were found to be very highly conserved across four species. CDXF sites are unique to region D and appeared twice close to each other conserved across four species. MYT1, PLZF, and NFκB were also unique to region D and showed conservation in four species. Other sites unique to region D and present in human were NKXH, MOKF, HOMF, RBIT and CLOX (Table 1 and Figure 4).

Many of the transcription factor binding sites identified in the sequences were found in clusters of two or more, adjacent to or overlapping one another. Region A transcription factor binding sites were localised to three clusters, with the largest harbouring five transcription factor binding sites. Region B had two clusters, Region C had five, two of which contained four sites each, and Region D contained nine clusters, although on average each cluster contained only two transcription factor binding sites (Figure 4).

Discussion

The identification of gene regulatory regions through comparative genomics is a powerful entrée to directed studies of gene regulation. Using this method we have identified, for the first time, four regions upstream of SRY that show high conservation between human, bovine, pig and goat. Furthermore, these regions of homology share transcription factor binding sites that appear to be subject to strong evolutionary pressure for conservation and may therefore be important for correct regulation of SRY.

Mouse Sry 5' sequences were found to be markedly dissimilar to other species across all regions of homology identified. This is perhaps not surprising given that mouse Sry coding sequences show particularly low homology to other species at the nucleotide and amino acid levels [7, 20]. Moreover, mouse Sry is expressed for a short, specific time, with detectable levels of Sry transcripts first appearing at 10.5 dpc and waning by 13.25 dpc [21, 22, 2, 23]. In other mammals, including humans, sheep, and pig, the gene remains actively transcribed into adulthood, albeit at a lower expression level than in fetal stages [24–27]. Therefore, mouse Sry evidently is regulated differently compared to other species and is therefore unlikely to have well conserved 5' regulatory regions.

Previous data bearing on the likely position of SRY regulatory elements has come from limited homology searches, transgenesis studies, and mutation analyses. Due to the unavailability of Y chromosome sequences from mammals other than mouse and human to date, minimal sequence has been available for homology studies. One study looked for conserved sequences upstream of SRY across ten species of mammal, including human, chimpanzee, gorilla, sheep, pig, bull, gazelle, mouse, rat, and guinea pig [28]. However, only 427 to 610 bp of 5' sequence was analysed, and no meaningful conservation was identified.

Boyer et al. (2006) used 3.3 kb and 5 kb of human SRY upstream sequence linked to human SRY coding sequence to produce transgenic mice, but only the larger fragment resulted in genital ridge expression of SRY. The same study showed that the pig 1.6 kb SRY promoter was sufficient for genital ridge expression [14]. Therefore we can postulate that the region necessary for genital ridge-specific regulation of SRY lies 5 kb upstream of the start of transcription in humans (corresponding to regions B, C and D from this study), and that this same site should be conserved in the pig 1.6 kb promoter (Region D). However, transgenic mouse models are subject to positional effects of the location of transgene insertion, which can cloud efforts to pinpoint gene regulatory sequences.

Two documented cases of mutations 5' of the coding region of SRY leading to pure gonadal dysgenesis have been reported in human. The first, a point mutation 75 bp 5' to the gene, was associated with male to female sex reversal. A nucleotide change from G to A, located in a motif conserved in primates, was found to be responsible [29], but this motif is not conserved in other species [30]. This mutation maps to region D of the present study. The second, a 25 kb deletion 1.7 kb upstream of human SRY was identified in a sex reversed patient [31]. The deletion would remove regions A-C and part of D, identified in the present study, supporting the hypothesis that regions A-D harbour important functional SRY regulatory elements, although the possibility that the deletion affects regulatory elements lying further 5' cannot be excluded as a cause of human sex reversal.

What transcription factor(s) may regulate expression of SRY? SRY is a master genetic switch that triggers testis development by initiating a cascade of gene expression. Its up-regulation marks the first male-specific gene expression event in the developing gonad. Therefore, any gene hypothesised to regulate SRY must be expressed equally in both sexes, before sex differentiation begins. Sf1, Sp1 and Wt1 are all expressed in genital ridges of both sexes and have been shown to influence expression of Sry in cell culture experiments [32–34]. Moreover, Sf1- and Wt1-knockout mice show gonadal sex development phenotypes [35, 36]. Other genes known to have a role in gonadal formation and development, based on experiments in genital ridges and the absence of gonads in knockout mice are Lim1 [37], Lhx9 [38], and Gata4 [39].

The present study identified binding sites for a number of transcription factors 5' of SRY. The transcription factor families whose binding sites displayed the highest levels of conservation were LHXF, CDXF, HOXF, PLZF and NFκB. These families all have members that are plausible candidates for a role in SRY regulation. The highly conserved LHXF binding site found in region C could potentially bind either LIM1 or LHX9 transcription factors. Lhx9 is expressed in the genital ridges of male and female mice between 9.5 and 11.5 dpc. Gonads fail to form in mice null for each of these genes [37, 38]. However, complete gonadal agenesis would implicate these genes in functions other than, or possibly additional to, regulation of Sry. PLZF and Nanog may bind to the HOXF and PLZF sites in the SRY 5' region, respectively. However, both are early germ cell transcription factors, and are therefore not present in the nuclei of supporting cell precursors in which SRY is expressed. NFκB is implicated in various stages of gonad development including spermatogenesis [40]. It is known to interact with AMH, and is likely have a role during the later stages of testis function, but expression in early gonadal development has not been described.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the two conserved CDXF binding sites in region D point to a role for CDX1 in SRY regulation (Figure 4). Cdx1 has been shown to be a direct target of retinoic acid [41], present in the gonads and mesonephroi of both sexes from an early stage [42, 43]. Cdx1 is expressed in the mesonephros in the developing mouse embryo and remains detectable till 12 dpc. Cdx1 knockout mice are viable and show homeotic vertebral transformations [44]. In view of the present data, it will be useful to examine the gonadal phenotype of these knockout mice.

Conclusion

In summary, we identified a large number of potential transcription factor binding sites localised to short regions of particularly high conservation in the SRY gene in human, bovine, porcine and caprine 5' flanking sequences. However, areas of high homology also exist that appear to lack binding sites for known transcription factors. These areas may also be important for the proper regulation of the gene by harbouring binding sites for unidentified proteins or transcription factors whose binding sites have not been characterized. The identification in the present study of regions of conservation upstream of SRY may facilitate the discovery of new mutations associated with human idiopathic XY sex reversal.

Methods

Bovine and goat SRY BAC sequence

The BAC clone RP42-95D10 from the CHORI BAC/PAC Resource Centre was previously identified as containing the bovine SRY coding region[17]. A 15 kb Sry fragment isolated from the BAC was cloned into pBluescript II KS+ using Eco RI, and shotgun sequenced by the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) Brisbane, to five times coverage. The BAC clone (library number 568E7) containing goat SRY [18], was obtained from Dr. Eric Pailhoux. Primers designed from bovine sequences (MotAf, 5'-TCCTTCCTTTTCTCCTTTGTTG-3'; MotAr, 5'-TGGCCAAAAA CTACTTGATGA-3'; MotBf, 5'-GGAACAGGAGAGATCATGAAACA-3'; MotBr, 5'-CTTCACCATTCCCACTCACC-3'; MotCf, 5'-AACTTACATGCACTTCATTCCA-3'; and MotCr, 5'-GAGGACTTCA AATATTAATGTCATCAT-3') were used to amplify and sequence regions from the goat BAC. Assembly of goat sequences was performed using Sequencher version 4.6 (Gene Codes Corporation).

Sequence alignment and binding site analysis

mVISTA http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml and SLAGAN (Shuffle-LAGAN) [45] were used for global alignment of the sequences after masking of repetitive elements. Conserved sequence blocks were analysed for conserved transcription factor binding sites using DiAlignTF software from Genomatix [46]. This analysis was carried out on the full-length conserved sequence blocks, as well as on core areas of high conservation found with ClustalW http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/ within each block. Each block was first checked for sites conserved across four species, then three species. Only transcription factor binding sites that showed homology across more than two species were included in this report. Matrix similarity scores for the conserved binding sites were calculated by the MatInspector software from Genomatix [46].

Abbreviations

- BAC:

-

bacterial artificial chromosome

- bp:

-

base pair

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- dpc:

-

days post coitum

- HMG:

-

high mobility group

- kb:

-

kilobase pair

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- SRY:

-

Sex determining region on the Y chromosome

References

Sinclair AH, Berta P, Palmer MS, Hawkins JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, Foster JW, Frischauf A-M, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN: A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature. 1990, 346: 240-244.

Koopman P, Munsterberg A, Capel B, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R: Expression of a candidate sex-determining gene during mouse testis differentiation. Nature. 1990, 348: 450-452.

Gubbay J, Koopman P, Collignon J, Burgoyne P, Lovell-Badge R: Normal structure and expression of Zfy genes in XY female mice mutant in Tdy. Development. 1990, 109 (3): 647-653.

Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian H, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R: Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature. 1991, 351: 117-121.

Graves JA: Evolution of the testis-determining gene – the rise and fall of SRY. Novartis Found Symposium. 2002, 244: 86-97. discussion 97–101, 203–106, 253–107,

Harley VR, Jackson DI, Hextall PJ, Hawkins JR, Berkovitz GD, Sockanathan S, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN: DNA Binding Activity of Recombinant SRY from Normal Males and XY Females. Science. 1992, 255 (5043): 453-456.

Whitfield LS, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN: Rapid sequence evolution of the mammalian sex-determining gene SRY. Nature. 1993, 364 (6439): 713-715.

Albrecht KH, Eicher EM: DNA sequence analysis of Sry alleles (subgenus Mus) implicates misregulation as the cause of C57BL/6J-Y(POS) sex reversal and defines the SRY functional unit. Genetics. 1997, 147 (3): 1267-1277.

Albrecht KH, Young M, Washburn LL, Eicher EM: Sry expression level and protein isoform differences play a role in abnormal testis development in C57BL/6J mice carrying certain Sry alleles. Genetics. 2003, 164 (1): 277-288.

Bullejos M, Koopman P: Delayed Sry and Sox9 expression in developing mouse gonads underlies B6-YDOM sex reversal. Developmental Biology. 2005, 278: 473-481.

Weitzman JB: Tracking evolution's footprints in the genome. J Biol. 2003, 2 (9–9.4):

Loots GG, Locksley RM, Blankespoor CM, Wang ZE, Miller W, Rubin EM, Frazer KA: Identification of a coordinate regulator of interleukins 4, 13, and 5 by cross-species sequence comparisons. Science. 2000, 288 (5463): 136-140.

Boffelli D, McAuliffe J, Ovcharenko D, Lewis KD, Ovcharenko I, Pachter L, Rubin EM: Phylogenetic shadowing of primate sequences to find functional regions of the human genome. Science. 2003, 299 (5611): 1391-1394.

Boyer A, Pilon N, Raiwet DL, Lussier JG, Silversides DW: Human and pig SRY 5' flanking sequences can direct reporter transgene expression to the genital ridge and to migrating neural crest cells. Developmental Dynamics. 2006, 235 (3): 623-632.

Miziara MN, Riggs PK, Amaral ME: Comparative analysis of noncoding sequences of orthologous bovine and human gene pairs. Genet Mol Res. 2004, 3 (4): 465-73.

Nordhoff V, Hubner K, Bauer A, Orlova I, Malapetsa A, Scholer HR: Comparative analysis of human, bovine, and murine Oct-4 upstream promoter sequences. Mamm Genome. 2001, 12 (4): 309-317.

Liu WS, de Leon FA: Assignment of SRY, ANT3, and CSF2RA to the bovine Y chromosome by FISH and RH mapping. Animal Biotechnology. 2004, 15 (2): 103-109.

Pannetier M, Tilly G, Kocer A, Hudrisier M, Renault L, Chesnais N, Costa J, Le Provost F, Vaiman D, Vilotte JL, et al: Goat SRY induces testis development in XX transgenic mice. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580 (15): 3715-3720.

Pilon N, Daneau I, Paradis V, Hamel F, Lussier JG, Viger RS, Silversides DW: Porcine SRY promoter is a target for steroidogenic factor 1. Biology of Reproduction. 2003, 68 (4): 1098-1106.

Daneau I, Houde A, Ethier JF, Lussier JG, Silversides DW: Bovine SRY gene locus: cloning and testicular expression. Biology of Reproduction. 1995, 52 (3): 591-599.

Bullejos M, Koopman P: Spatially dynamic expression of Sry in mouse genital ridges. Developmental Dynamics. 2001, 221 (2): 201-205.

Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R: Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995, 121: 1603-1614.

Jeske YW, Bowles J, Greenfield A, Koopman P: Expression of a linear Sry transcript in the mouse genital ridge. Nature Genetics. 1995, 10 (4): 480-482.

Hanley NA, Hagan DM, Clement-Jones M, Ball SG, Strachan T, Salas-Cortes L, McElreavey K, Lindsay S, Robson S, Bullen P, et al: SRY, SOX9, and DAX1 expression patterns during human sex determination and gonadal development. Mechanisms of Development. 2000, 91 (1–2): 403-407.

Payen E, Pailhoux E, Abou Merhi R, Gianquinto L, Kirszenbaum M, Locatelli A, Cotinot C: Characterization of ovine SRY transcript and developmental expression of genes involved in sexual differentiation. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 1996, 40 (3): 567-575.

Parma P, Pailhoux E, Cotinot C: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of genes involved in gonadal differentiation in pigs. Biology of Reproduction. 1999, 61 (3): 741-748.

Daneau I, Ethier JF, Lussier JG, Silversides DW: Porcine SRY gene locus and genital ridge expression. Biology of Reproduction. 1996, 55 (1): 47-53.

Margarit E, Guillen A, Rebordosa C, Vidal-Taboada J, Sanchez M, Ballesta F, Oliva R: Identification of Conserved Potentially Regulatory Sequences of the SRY Gene from 10 Different Species of Mammals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998, 245 (2): 370-7.

Veitia RA, Fellous M, McElreavey K: Conservation of Y chromosome-specific sequences immediately 5' to the testis determining gene in primates. Gene. 1997, 199 (1–2): 63-70.

Poulat F, Desclozeaux M, Tuffery S, Jay P, Boizet B, Berta P: Mutation in the 5' noncoding region of the SRY gene in an XY sex-reversed patient. Hum Mutat. 1998, S192-194. Suppl 1,

McElreavy K, Vilain E, Abbas N, Costa J-M, Souleyreau N, Kucheria K, Boucekine C, Thibaud E, Brauner R, Flamant F, et al: XY sex reversal associated with a deletion 5' to the SRY "HMG box" in the testis-determining region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992, 89: 11016-11020.

de Santa Barbara P, Mejean C, Moniot B, Malcles MH, Berta P, Boizet-Bonhoure B: Steroidogenic factor-1 contributes to the cyclic-adenosine monophosphate down-regulation of human SRY gene expression. Biology of Reproduction. 2001, 64 (3): 775-783.

Desclozeaux M, Poulat F, de Santa Barbara P, Soullier S, Jay P, Berta P, Boizet-Bonhoure B: Characterization of two Sp1 binding sites of the human sex determining SRY promoter. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998, 1397 (3): 247-252.

Hossain A, Saunders GF: The human sex-determining gene SRY is a direct target of WT1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001, 276 (20): 16817-16823.

Ingraham HA, Lala DS, Ikeda Y, Luo X, Shen WH, Nachtigal MW, Abbud R, Nilson JH, Parker KL: The nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 acts at multiple levels of the reproductive axis. Genes Dev. 1994, 8 (19): 2302-12.

Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenisch R: WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993, 74 (4): 679-691.

Shawlot W, Wakamiya M, Kwan KM, Kania A, Jessell TM, Behringer RR: Lim1 is required in both primitive streak-derived tissues and visceral endoderm for head formation in the mouse. Development. 1999, 126 (22): 4925-4932.

Birk OS, Casiano DE, Wassif CA, Cogliati T, Zhao L, Zhao Y, Grinberg A, Huang S, Kreidberg JA, Parker KL, et al: The LIM homeobox gene Lhx9 is essential for mouse gonad formation. Nature. 2000, 403 (6772): 909-913.

Molkentin JD, Olson EN: GATA4: a novel transcriptional regulator of cardiac hypertrophy?. Circulation. 1997, 96 (11): 3833-3835.

Delfino F, Walker WH: Stage-specific nuclear expression of NF-kappaB in mammalian testis. Molecular Endocrinology. 1998, 12 (11): 1696-1707.

Houle M, Prinos P, Iulianella A, Bouchard N, Lohnes D: Retinoic acid regulation of Cdx1: an indirect mechanism for retinoids and vertebral specification. Mol Cell Biol. 2000, 20 (17): 6579-86.

Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, Mamiya S, Yashiro K, Chawengsaksophak K, Wilson MJ, Rossant J, et al: Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006, 312 (5773): 596-600.

MacLean G, Li H, Metzger D, Chambon P, Petkovich M: Apoptotic extinction of germ cells in testes of Cyp26b1 knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2007, 148 (10): 4560-4567.

Subramanian V, Meyer BI, Gruss P: Disruption of the murine homeobox gene Cdx1 affects axial skeletal identities by altering the mesodermal expression domains of Hox genes. Cell. 1995, 83 (4): 641-653.

Brudno M, Malde S, Poliakov A, Do CB, Couronne O, Dubchak I, Batzoglou S: Glocal alignment: finding rearrangements during alignment. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2003, 19 (Suppl 1): i54-62.

Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T: MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2005, 21 (13): 2933-2942.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eric Pailhoux for the goat BAC clone, and Sean McWilliam for help with the comparative genomic and bioinformatic analyses. This work was supported by research grants from CSIRO Livestock Industries "Food Futures" flagship, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Australian Research Council (ARC). DF is supported by a CSIRO/IMB Postgraduate Research Award, and PK is a Federation Fellow of the ARC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DR, JB, PK and SL designed the study. DR executed all of the experiments. DR, JB, PK and SL wrote and proof-read the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12867_2008_342_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Multiple sequence alignment of Region A, B, C and D with transcription factor binding sites. ClustalW alignment of the four regions across human, bovine, caprine, porcine and mouse sequences with conserved transcription factor binding sites indicated using grey shading or boxing of relevant nucleotides. More detailed information on particular transcription factor families found per page are shown to the right of each alignment. (DOC 156 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, D.G., Bowles, J., Koopman, P. et al. New insights into SRY regulation through identification of 5' conserved sequences. BMC Molecular Biol 9, 85 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2199-9-85

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2199-9-85