Abstract

Background

Maleness in mammals is genetically determined by the Y chromosome. On the Y chromosome SRY is known as the mammalian male-determining gene. Both placental mammals (Eutheria) and marsupial mammals (Metatheria) have SRY genes. However, only eutherian SRY genes have been empirically examined by functional analyses, and the involvement of marsupial SRY in male gonad development remains speculative.

Results

In order to demonstrate that the marsupial SRY gene is similar to the eutherian SRY gene in function, we first examined the sequence differences between marsupial and eutherian SRY genes. Then, using a parsimony method, we identify 7 marsupial-specific ancestral substitutions, 13 eutherian-specific ancestral substitutions, and 4 substitutions that occurred at the stem lineage of therian SRY genes. A literature search and molecular dynamics computational simulations support that the lineage-specific ancestral substitutions might be involved with the functional differentiation between marsupial and eutherian SRY genes. To address the function of the marsupial SRY gene in male determination, we performed luciferase assays on the testis enhancer of Sox9 core (TESCO) using the marsupial SRY. The functional assay shows that marsupial SRY gene can weakly up-regulate the luciferase expression via TESCO.

Conclusions

Despite the sequence differences between the marsupial and eutherian SRY genes, our functional assay indicates that the marsupial SRY gene regulates SOX9 as a transcription factor in a similar way to the eutherian SRY gene. Our results suggest that SRY genes obtained the function of male determination in the common ancestor of Theria (placental mammals and marsupials). This suggests that the marsupial SRY gene has a function in male determination, but additional experiments are needed to be conclusive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sex determination systems are different among organisms, and flexibly evolved. In species in which male development is genetically determined, a sex-determining gene on the sex chromosomes is a dominant inducer of sex determination. The sex-determining gene is expressed in male bi-potential gonads, and enhances testis formation by regulating specific downstream genes and signaling pathways. It is believed that the origin of male-determining genes is different in mammals and fishes, and that it has independently evolved in several lineages [1,2,3,4].

In eutherian (placental) mammals such as humans and mice, the sex-determining region on Y (SRY) is the male-determining gene [1, 2]. The SRY gene is a transcription factor, and has a high-mobility group (HMG) domain (~78 amino acids). The HMG domain binds in the minor groove of specific DNA sequences, resulting in substantial DNA bending [5,6,7]. The protein complex of SRY and steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1 or also called NR5A1/Ad4BP) directly binds the testis enhancer of sry-box 9 (SOX9) core (TESCO), and up-regulates the expression of SOX9 [8, 9]. SOX9 drives testis development by mediating certain pathways, and maintains Sertoli cell specification by activating fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling and Prostaglandin D2 (Pgd2) signaling [10, 11]. Sertoli cells produce anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), causing regression of the female Müllerian ducts, and facilitate spermatogenesis and the differentiation of androgen-producing Leydig cells [10].

In mammals, SRY has been identified in only marsupial and eutherian mammals [12, 13]. This means that SRY evolved in an ancestor of Theria (marsupial and eutherian mammals). This is consistent with the observation that SRY does not exist in Monotremata (monotremes) such as platypuses and echidnas [12, 13]. However, the function of marsupial SRY is not fully understood, because to date there have been no functional assays or transgenic analyses performed using the marsupial SRY gene. It is not clear whether the marsupial SRY gene has a function in male determination, nor when SRY obtained the male determining function during the therian evolution. In general, SRY is expressed earlier than SOX9 in the male wallaby newborn as well as the human fetus [14]. Although the eutherian SRY gene is expressed mainly in the testis and brain, the wallaby SRY gene is expressed in a broad range of tissues including testis, brain, kidney and mesonephros [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. It is of interest to ask whether the marsupial SRY gene has a function in male determination or not [23].

In this study, we clarify the sequence difference between marsupial and eutherian SRY genes using the currently available SRY sequences, and indicate how the marsupial SRY gene is similar to the eutherian SRY gene. We then identify ancestral substitutions of the SRY gene at the marsupial, eutherian or therian common ancestor. We test whether the marsupial SRY gene is able to control the expression of SOX9 via the TESCO system in a similar way to the eutherian SRY gene. We also perform computational analyses of the molecular evolution and molecular dynamics, and show the evolutionary process of the therian SRY gene.

Results

The molecular evolution of the therian SRY gene

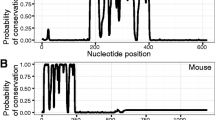

Fig. 1 shows the alignment of amino acid sequences of HMG domain in SRY genes. We use SOX1, SOX2 and SOX3 genes that are included in SOXB1 group, and it is believed that SRY and SOX3 genes originated from a common ancestral gene [13, 24]. The sea squirt genome has only one gene of the SOXB1 group, and the gene is an ancestral one of the vertebrate SOXB1 group. Although the regions outside of the HMG domain are not at all aligned between marsupial and eutherian SRY genes, the HMG domain is highly conserved in Theria (Fig. 1). The HMG domain has ~72.8% similarity between marsupials and eutherians, and ~85.1% and ~78.7% similarity within marsupials and eutherians, respectively. We computed dn/ds using the pairwise comparison of the alignment of the entire gene, and the ratio revealed that the SRY sequence was under purifying selection (overall dn/ds = 0.16). Fig. 2 shows a NJ tree of SRY and SOX1–3 genes. The topology of the tree obtained from NJ method is the same as that obtained from the other three methods (ME, MP and ML). We found that therian SRY genes were monophyletic, and the SOX3 and SRY genes formed one cluster (Fig. 2). This means that SRY and SOX3 originated from the common ancestral gene before the divergence of Theria, and it is consistent with previous studies [13, 24]. The interior branch of the stream lineage of the therian SRY genes is longer than that of the SOX3 genes, although the difference of the branch length between the stem lineage of SOX3 and SRY genes is not statistically significant (P > 0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

Comparison of HMG domain in SRY and SOX genes. The amino acid sequence alignment of HMG domain is shown. The gray box represents the position of the HMG domain. Eutherian-specific substitutions are indicated in blue, and marsupial-specific substitutions are indicated in green. The substitutions common to Theria are indicated in yellow. This information is also shown in Additional file 1: Table S1

In the HMG domain, SRY has 48 amino acid differences compared to SOX3 (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Of the substitutions, using the parsimonious method, the number of ancestral substitutions is estimated. Fig. 3 shows the ancestral substitutions that occurred in the common ancestor of Theria, marsupial or eutherian mammals, separately. Our results show that four substitutions occurred in the stem branch of Theria, and seven and 13 substitutions occurred in the stem branch of marsupial and eutherian mammals, respectively (Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Of the 13 eutherian substitutions, three amino acid residues (I55F, K59Q and E68K) have been conserved in the eutherian species used in this study. In marsupials, one amino acid residue (V64 K) has been conserved in the species used.

Inferred ancestral substitutions are shown on the tree by parsimony. Four substitutions were specific to the branch that SRY differentiated from SOX3 in the ancestor of Theria. 13 substitutions were on the branch containing the eutherian SRY, and seven substitutions were on the branch containing the marsupial SRY. The divergence time on the tree, 79 or 105 MYA coincides with the radiation of marsupials or eutherians, and 210–180 MYA is the divergence time of monotremes and Theria

The protein structure of the therian SRY gene

To compare the protein structure of SRY genes between marsupials and eutherians, DNA binding affinities of several SRY HMG domains were investigated using the MM/PB-SA method (See methods and Additional file 1: Table S2). In the simulation we predict marsupial (wallaby) SRY-DNA structure based on the human SRY-DNA 3-D structure, and find that wallaby SRY interacts with DNA through 9 amino acid residues (Additional file 1: Table S3). The marsupial (wallaby) HMG domain can bind DNA (binding energy: −208.53 kcal/mol), but the binding affinity is a little weaker than that of the human SRY HMG (binding energy: −243.42 kcal/mol; Fig. 4 and Additional file 1: Table S4). However, it is difficult to conclude whether the wallaby SRY is functionally similar to the human SRY from these computations.

Estimated binding energy of SRY protein and DNA. The vertical axis shows the estimated binding energy (kcal/mol) of SRY proteins and DNA. The horizontal axis shows the pair of proteins and DNA. Each box length represents a mean, and each error bar represents standard deviation for 100 snapshots. The smaller values mean high affinity of proteins-DNA binding. hW_H is a pair of human wild type protein and human DNA, wW_H is a pair of wallaby wild type protein and human DNA, and wW_W is a pair of wallaby wild type protein and wallaby DNA. hF55I_H, hY69F_H, hQ59K_H, hK68E_H, and hM9I_H are pairs of human mutant type protein and human DNA. It was reported that hM9I_H shows abnormal structure (Murphy et al. 2001). wK64V_W is a pair of wallaby mutant type protein and wallaby DNA. See Additional file 1: Table S2 for more details of the pairs. The values are shown in Additional file 1: Table S4

Amino acids conserved in the marsupial or eutherian mammals might affect the binding affinity, and we introduced mutations into wallaby or human amino acids in silico at positions conserved (See Material and Methods). Of the human mutant proteins, only K68E is predicted to exhibit lower binding affinity than the wild-type proteins (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Table S4). K at the position 68 is well conserved in the eutherian SRY, although the function of the amino acid residue is unknown. The other mutant proteins in the human and wallaby rather show relatively higher binding affinity than the wild-type proteins (Fig. 4; Additional file 1: Table S4). This result suggests the conserved amino acids affect the binding affinity of SRY, but does not show that all the conserved amino acids work for higher binding affinity.

Additional file 1 Table S1 shows functionally important amino acid residues in the SRY gene [7, 25]. The important amino acid residues are evolutionarily conserved except for the positions 55 and 69. In human SRY, the phenylalanine (F55) and tyrosine (Y69) maintain the protein structure by anchoring the C-terminal tail and DNA-helix to the N-terminal tail, and F55 is involved in packing interactions between the N-terminal and a DNA-helix [7]. However, in the SOX and marsupial SRY genes (with the exception of the bandicoot SRY gene), position 55 is an isoleucine (I), (Fig. 1). The I is likely an ancestral amino acid residue, changed to F in the stem lineage of eutherian mammals (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). The I55F substitution is not accompanied by the change of amino acid polarity. On the other hand, at position 69, three different kinds of amino acid substitutions are observed in marsupials: F in Diprotodontia, serine (S) in the dunnart and histidine (H) in the opossum (Fig. 1). In this case, an ancestral amino acid residue in marsupials at position 69 is Y. Two marsupial groups of the possum and bandicoot have the ancestral residue at the position 69 (Fig. 1), thus the substitution independently occurred in the three marsupial groups. Although the function of the amino acid residue is unknown, the physico-chemical characteristic of the amino acid residue (Y) in the eutherian SRY is slightly different from that (F, S, or H) in the marsupial SRY

The functional assay of the marsupial SRY gene

Although we observed different patterns of substitutions in marsupial SRY genes from eutherian SRY genes and that the function (DNA-binding ability) of wallaby (marsupial) SRY and human (eutherian) SRY appears to be similar, the function of marsupial SRY is still unclear. We attempted to test whether or not marsupial SRY genes have a similar function to eutherian SRY genes as a transcriptional factor, and performed a biochemical assay of wallaby SRY genes in a human cell culture system of NT2/D1 cells. We investigated whether the wallaby SRY protein can activate SOX9 transcription in the same manner as human SRY using SOX9 enhancer reporter gene luciferase assays. In the assay, human SRY (or SOX9) with SF1 can up-regulate the luciferase expression via the mouse TESCO [9]. When we co-transfect human SRY and SF1 expression vectors into NT2/D1 cells, the luciferase activity is increased (Fig. 5). Wallaby SRY also activated SOX9 enhancer activity, although the level of the enhancer activation by wallaby SRY/SF1 is less than that by human SRY/SF1. This suggests that function of wallaby SRY could be comparable with human SRY.

Luciferase reporter assays using SRY, Sox9, and SF1. The blue bar shows the luciferase values using TESCO-E1b-luc promoters. The red bar shows the luciferase values using only E1b-luc as a negative control. Horizontal axis indicates pairs of co-transfected vectors. (a) The vertical axis indicates raw luciferase values. (b) The vertical axis indicates fold changes over the raw luciferase value of SF1

Discussion

The function of marsupial SRY genes

Whether or not SRY is a sex determination gene in marsupials remains debatable [12, 22, 23, 26, 27]. Our results suggest that marsupial SRY is functionally similar to eutherian SRY, and indicate that marsupial SRY is a male determining gene. This is the first report showing that the marsupial SRY activates the SOX9 gene.

SRY mutations causing disorders of sex development (DSD), including gonadal dysgenesis and hermaphroditism, have been reported at 25 positions within HMG domain [25]. At those sites, most of the amino acid residues are strongly conserved, but one exception is observed at position 9 in the agile wallaby SRY gene (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). In the agile wallaby, a substitution from methionine (M) to leucine (L) has happened. An amino acid change from M to isoleucine (M9I) causes 46XY sex reversal in humans [7]. This substitution increases the angle of the bend in the DNA, and the abnormal bend may prevent distally placed proteins from interacting with a transcriptional initiation complex [7]. L and I are two of the four isomeric amino acids and the only difference between them is a position of CH3 in the side chain, and thus they have a similar physicochemical characteristic. We expect the substitution of I instead of L have a similar effect. This suggests that the SRY protein might not be functional during male determination in the agile wallaby.

The perspective for molecular coevolution of the SRY gene

The evolution of SRY probably consisted of two steps. The first step is the differentiation from SOX3 to SRY in the common ancestor of Theria. Our study estimates four substitutions in the stem lineage of Theria (during ~30 million years). Indeed, the tempo of the amino acid substitutions in the therian ancestor is significantly faster than that in the eutherian or marsupial ancestor (Fisher’s exact test; P < 0.001). This suggests a possibility of the functional diversification of SRY from SOX3 in the therian ancestor, but the biological meaning of the four substitutions or functional diversification is unknown. A previous study showed that ectopic SOX3 could activate SOX9 in the same way as SRY in mice [28]. Therefore, SOX3 might have a potential function for male determination, but as SOX3 is not expressed in the developing testis this precludes it from working as a male determination gene in nature. The changes of the expression pattern were necessary [29], so that the ancestral SOX3 could reach the top of the sex determination system as SRY. Moreover, the differentiation of protein sequences was essential for the therian ancestral gene to acquire the SRY functions.

The second step in the evolution of the SRY gene caused the functional difference between the marsupial and eutherian genes. In the eutherian ancestor, SRY probably obtained the ability to functionally interact with SF-1 and SOX9, and the SRY and SF-1 proteins could bind the SOX9 enhancer (TESCO). Our result indicates that the marsupial SRY can use the eutherian TESCO, but the TESCO sequence does not exist in marsupials [8, 30]. The upstream region of SOX9 in marsupials has only partial consensus sequences of the SRY and SF-1 binding sites, although there is a possibility that marsupials have a testis enhancer of SOX9 at a different position. We also found a difference in amino acid sequences between the marsupial and eutherian SRY genes, and the marsupial SRY interacted with DNA weakly compared to eutherian SRY. The sequence differences between the marsupial and eutherian SRY might affect the stability of protein-DNA complex.

The evolution of SRY is associated with the sub-functionalization of duplicate genes. One of the duplicate genes accumulates mutations, and sometimes reinforces one of the functions that the ancestral gene has [31]. Although SOX3 and SRY are homologous non-recombining genes shared between the X and Y called gametologs, SOX3 is the ancestral gene, and SRY is the reinforced new one. The sub-functionalization of SRY might be involved in leading to the emergence of sex chromosomes in Theria.

Conclusion

In this study, we showed that the marsupial SRY could work as a transcription factor in a human cell culture system, and could substitute for human SRY in the TESCO assay. Our study suggests that the marsupial SRY is functionally similar to the eutherian SRY. We found several sequence differences between the marsupial and eutherian SRY genes, and these sequence differences support functional differences between the marsupial and eutherian SRY genes including a different range of DNA-binding affinity in the proteins.

Materials and methods

Nucleotide sequences and animal samples used in the analysis

Nucleotide sequence data and corresponding gene information were obtained from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Ensembl databases (release 62; http://uswest.ensembl.org/index.html). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. A BLAST search was carried out using the human or wallaby SRY genes as a query to identify SRY homologs in eutherian and marsupial species. We found SRY sequences from 72 species (49 eutherians; 23 marsupials), but after exclusion of the same sequences in closely related species, 14 sequences from eutherians and ten sequences from marsupials were compared for coding region sequences. Of the ten marsupial SRYs, seven were published: brush-tailed possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), northern brown bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus), agile wallaby (Macropus agilis), tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii), brush-tailed rock wallaby (Petrogale penicillata), striped-faced dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura) and opossum (Monodelphis domestica), and three were obtained in this study as follows.

We experimentally identified three marsupial SRY homologs (accession numbers: LC111530; LC111531; LC111532) because published SRYs are limited and some are truncated. Liver and spleen samples were collected from swamp wallabies (Wallabia bicolor), eastern gray kangaroos (Macropus giganteus), and koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Those samples were donated from Kanazawa Zoo in Yokohama City, Japan, and informed consent for use of the samples was written. Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Genomic DNA (100 ng) was suspended in 50 μl of 1×Ex Taq PCR buffer, which contained 0.2 μM of each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTP), 0.5 μM of the one pair of primers, and 1 unit of TaKaRa Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa). The oligonucleotide primers used are F-TTGAGTCCGTGAAAAGTGGGTC and R-TTGTGAATCTGCCACGCTTGTC for swamp wallabies and koalas and F-GCTATGTATGGCTTCTTGAATG and R-AACTGTCATTCGTTTCAGGT for eastern gray kangaroos [22, 32, 33]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification included one cycle at 95 °C for 30 s followed by 30–40 cycles of denaturing for 15 s at 95 °C, annealing for 30–60 s at 50–60 °C, and extension for 60 s at 72 °C. A final extension was performed for 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN), or they were subcloned using the TOPO XL PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen). In the case of direct sequencing, PCR products were purified with ExoSAP-IT (United States Biochemical) for 30 min at 37 °C followed by 15 min at 80 °C. Those purified products were sequenced. The sequencing reactions were performed using the dideoxy chain-termination method [34] using BigDye Terminator v1.1 or 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems), and the sequencing reactions were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3130 genetic analyzer.

Phylogenetic and data analyses

The nucleotide sequences were aligned using Clustal X [35], and the results were also checked manually. The entire alignment is available upon request. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using all four methods available in the MEGA4.1 program [36] and MEGA6.06 [37]: neighbor-joining (NJ) [38], minimum evolution (ME) [39], maximum parsimony (MP) [40] and maximum likelihood (ML) [41]. The reliability of the trees was assessed by bootstrap re-sampling with 1000 replications. Phylogeny inference package version 3.68 (PHYLIP) [42] and phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood (PAML) [43] were also used to construct a phylogeny based on ML.

Details of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

We performed MD simulations of 9 systems to analyze the binding affinity of human- or marsupial-DNA to SRY proteins. The DNA-protein pairs used in this analysis are shown in Additional file 1: Table S2. 6 mutant proteins were selected in order to understand the functional importance of an amino acid residue that was evolutionary conserved in the eutherian or marsupial SRY genes. The mutant proteins had a point mutation at the conserved amino acid residue, and we investigated the binding affinity between the mutant proteins and DNA. At positions 55, 59 and 68, three amino acid residues are eutherian-specific and evolutionary conserved in all the eutherians used. An amino acid residue at a position 64 is marsupial-specific and conserved in all the marsupials used. These amino acid residues might be important for a function in the SRY, and were changed to the ancestral one in silico. At a position 69, an amino acid residue (Y) is conserved well in SOX3 and SRY except for some marsupials (Diprotodontia, the dunnart and opossum). The amino acid residue might be important in the eutherian but not in the marsupial one. The amino acid residue (Y) in the human protein was changed to the Diprotodontia (wallaby) one (F). The amino acid residues at positions 55 and 69 are also essential to the human protein structure (Additional file 1: Table S1). The detail of M9I mutation was explained in Discussion [7]. The regulatory region of the human Amh was used as SRY protein binding sequence [7]. In addition, marsupial SRY binding sequence was used for the MD simulations and was identified from the 5′ regulatory regions of the wallaby and opossum SRY genes using MatInspector [44]. All initial structures were modeled by using modeling software MOE (Chemical Computing Group Inc.) based on nuclear magnetic resonance structure of human SRY HMG domain bound to a 14 nucleotide sequence (PDB ID: 1 J46) [7]. For the mutant proteins, the mutated residues were replaced manually by using MOE. These initial structures were solvated with explicit water molecules in a rectangular box, and counter ions (Na+ and Cl−) were added for neutralizing the protein’s charge. The minimum distance between a protein atom and the water wall was 12 Å. We did the energy minimization of the entire system, and then gradually increased the system’s temperature to 310 K using the Berendsen thermostat [45]. For each system, a 50-ns production run in the NPT ensemble was performed. The temperature of the system was controlled at 310 K using a Langevin thermostat. All simulations were carried out by using AMBER software package version 12 [46]. The simulations were done using a periodic boundary condition, and the long-range electrostatic interactions were treated using the particle-mesh Ewald method [47, 48]. We applied the ff99SB-ildn-NMR force field [49, 50] for amino acids and TIP3P model [51] for water molecules. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained by the SHAKE [52] and SETTLE [53] algorithms, and the time step of 1 fs was used.

Analysis of binding affinity between DNA and proteins

The DNA-binding affinity of HMG domains from eutherian, marsupial, or mutant SRY proteins was investigated from the trajectories of MD simulations. The binding energies between proteins and DNA were estimated by using the molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann and surface area (MM/PB-SA) method [54,55,56,57,58]. In MM/PB-SA method the binding free energy is calculated as

In the analysis of the binding energies, the water molecules were replaced with implicit solvation models. The conformations of the apoprotein (SRY) and free ligand (DNA) were extracted from the set of structures of protein/DNA complex for calculating G(apoprotein) and G(free ligand) in Eq. (1). < > denotes an average over a set of structures along an MD trajectory. Einternal includes the bond, angle, and torsion angle energies, and Eelectrostatic and EvdW are intermolecular electrostatic and vdW energies, respectively. The Gsolvationpolar was calculated by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation with Delphi program [59]. The dielectric constants for the solute and surrounding solvent were 1.0 and 80.0, respectively. In this study the entropy was not calculated. The MD trajectory was collected for a 30 ns (from 20 to 50 ns) with a time step of 300 ps for each system.

Cell culture and transfections

We evaluated the function of marsupial SRY in a human embryonic carcinoma cell line, NT2/D1, as a model of presumptive Sertoli cells [9]. Ethics approval is not necessary for research use of cell lines within Australia. NT2/D1 cell-lines (obtained from ATCC CRL-1973) were grown as an adherent monolayer in DMEM:F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (GIBCO) and 5% penicillin/streptomycin and were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in a humidifying incubator (NU AIRE). Cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates at a density of 200,000 cells per well. Cells were grown for 24 h before the transfection of DNA. Transient transfections were conducted using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche). The protocol required the use of a ratio of X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent to DNA of 3:1. Plasmid DNA was added to X-tremeGENE 9 in growth media and incubated for 20 min before addition to cells. Cell lysates were harvested after 48 h for reporter assays.

Expression and reporter plasmids

Expression vector is a plasmid of pcDNA3 origin (Clontech) for all mammalian genes. Marsupial SRY ORF was amplified by PCR from tammar wallaby male genome DNA from Water Paul in Australian National University using a forward primer, ATCATAGATCTGCCACCATGTACCCATACGATGTTCCGGATTACGCTAGCCATATGTATGGCTTCTTGAATGTA, which is containing BamHI, FLAG and KOZAK sequences and a reverse primer, TTAGAAACTGTCATTCGTTTC, which replaces the stop codon with an EcoRI restriction site [9, 60]. The marsupial SRY clone was sub-cloned into pcDNA3. The mouse TESCO sequence was sub-cloned into E1b-luciferese vector [9]. Each HA-tagged human SF1 and SOX9 expression plasmid is previously described [9, 61]. It notes that a marsupial-originated plasmid is only SRY clone, but other SF1/SOX9/TESCO plasmids originate from human or mouse sequences because the sequences are highly conserved in Theria [8, 30, 62, 63].

Luciferase reporter assays

At 48 h post-transfection the culture media was removed from 12-well plates and cells were washed twice with 100 μl PBS per well. 100 μl of 1 x Reporter Lysis buffer (Promega) was added to each well and placed onto a shaker at room temperature for 10 min. Plates were then tapped gently to lift cells. Lysed cells were then collected and placed into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at top speed, and supernatant was used in reporter assays. For Luciferase reporter assays, 100 μl of the cell extract was added to a 96-well Luciferase plate. 100 μl of 2X Luciferase assay buffer was then added to each well. Luminescence readings at 405 nm were instantly measured, and Luciferase activity was determined. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s T-test.

Abbreviations

- 3-D:

-

three-dimensional

- AMH:

-

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- DSD:

-

Disorders of sex development

- F:

-

Phenylalanine

- FGF:

-

Fibroblast growth factor

- H:

-

Histidine

- HMG:

-

High-mobility group

- I:

-

Isoleucine

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics

- ME:

-

Minimum evolution

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- MM/PB-SA:

-

Molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann and surface area

- MP:

-

Maximum parsimony

- NJ:

-

Neighbor-joining

- PAML:

-

Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood

- Pgd2:

-

Prostaglandin D2

- PHYLIP:

-

Phylogeny inference package

- S:

-

Serine

- SF1:

-

Steroidogenic factor 1

- SOX:

-

Sry-box

- SRY:

-

Sex-determining region on Y

- TESCO:

-

Testis enhancer of Sox9 core

- Y:

-

Tyrosine

References

Sinclair AH, Berta P, Palmer MS, Hawkins JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, Foster JW, Frischauf AM, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PNA. Gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature. 1990;346:240–4.

Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature. 1991;351:117–21.

Matsuda M, Nagahama Y, Shinomiya A, Sato T, Matsuda C, Kobayashi T, Morrey CE, Shibata N, Asakawa S, Shimizu N, et al. DMY is a Y-specific DM-domain gene required for male development in the medaka fish. Nature. 2002;417:559–63.

Myosho T, Otake H, Masuyama H, Matsuda M, Kuroki Y, Fujiyama A, Naruse K, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M. Tracing the emergence of a novel sex-determining gene in medaka, Oryzias Luzonensis. Genetics. 2012;191:163–70.

Harley VR, Jackson DI, Hextall PJ, Hawkins JR, Berkovitz GD, Sockanathan S, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PNDNA. Binding activity of recombinant SRY from normal males and XY females. Science. 1992;255:453–6.

Pontiggia A, Rimini R, Harley VR, Goodfellow PN, Lovell-Badge R, Bianchi ME. Sex-reversing mutations affect the architecture of SRY-DNA complexes. EMBO J. 1994;13:6115–24.

Murphy EC, Zhurkin VB, Louis JM, Cornilescu G, Clore GM. Structural basis for SRY-dependent 46-X,Y sex reversal: modulation of DNA bending by a naturally occurring point mutation. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:481–99.

Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R. Sex determination involves synergistic action of SRY and SF1 on a specific Sox9 enhancer. Nature. 2008;453:930–4.

Knower KC, Kelly S, Ludbrook LM, Bagheri-Fam S, Sim H, Bernard P, Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R, Harley VR. Failure of SOX9 regulation in 46XY disorders of sex development with SRY, SOX9 and SF1 mutations. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17751.

Brennan J, Capel B. One tissue, two fates: molecular genetic events that underlie testis versus ovary development. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:509–21.

Adam IR, McLaren A. Sexually dimorphic development of mouse primordial germ cells: switching from oogenesis to spermatogenesis. Development. 2002;129:1155–64.

Foster JW, Brennan FE, Hampikian GK, Goodfellow PN, Sinclair AH, Lovell-Badge R, Selwood L, Renfree MB, Cooper DW, Graves JA. Evolution of sex determination and the Y chromosome: SRY-related sequences in marsupials. Nature. 1992;35:531–3.

Wallis MC, Waters PD, Delbridge ML, Kirby PJ, Pask AJ, Grützner F, Rens W, Ferguson-Smith MA, Graves JA. Sex determination in platypus and echidna: autosomal location of SOX3 confirms the absence of SRY from monotremes. Chromosom Res. 2007;15:949–59.

Pask AJ, Calatayud NE, Shaw G, Wood WM, Renfree MB. Oestrogen blocks the nuclear entry of SOX9 in the developing gonad of a marsupial mammal. BMC Biol. 2010;8:113.

Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995;121:1603–14.

Lahr G, Maxson SC, Mayer A, Just W, pilgrim C, Reisert I. Transcription of the Y chromosomal gene, Sry, in adult mouse brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;33:179–82.

Hanley NA, Hagan DM, Clement-Jones M, Ball SG, Strachan T, Salas-Cortés L, McElreavey K, Lindsay S, Robson S, Bullen P, et al. SRY, SOX9, and DAX1 expression patterns during human sex determination and gonadal development. Mech Dev. 2000;91:403–7.

Mayer A, Lahr G, Swaab DF, Pilgrim C, Reisert I. The Y-chromosomal genes SRY and ZFY are transcribed in adult human brain. Neurogenetics. 1998;1:281–8.

Daneau I, Houde A, Ethier JF, Lussier JG, Silversides DW, Bovine SRY. Gene locus: cloning and testicular expression. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:591–9.

Payen E, Pailhoux E, Abou Merhi R, Gianquinto L, Kirszenbaum M, Locatelli A, Cotinot C. Characterization of ovine SRY transcript and developmental expression of genes involved in sexual differentiation. Int J Dev Biol. 1996;40:567–75.

Parma P, Pailhoux E, Cotinot C. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of genes involved in gonadal differentiation in pigs. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:741–8.

Harry JL, Koopman P, Brennan FE, Graves JA, Renfree MB. Widespread expression of the testis-determining gene SRY in a marsupial. Nat Genet. 1995;11:347–9.

Graves JA, Renfree MB. Marsupials in the age of genomics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:393–420.

Katoh K, Miyata TA. Heuristic approach of maximum likelihood method for inferring phylogenetic tree and an application to the mammalian SOX-3 origin of the testis-determining gene SRY. FEBS Lett. 1999;463:129–32.

Assumpção JG, Benedetti CE, Maciel-Guerra AT, Guerra G, Baptista MT, Scolfaro MR, de Mello MP. Novel mutations affecting SRY DNA-binding activity: the HMG box N65H associated with 46,XY pure gonadal dysgenesis and the familial non-HMG box R30I associated with variable phenotypes. J Mol Med. 2002;80:782–90.

Graves JA. Interactions between SRY and SOX genes in mammalian sex determination. BioEssays. 1998;20:264–9.

Pask AJ, Harry JL, Renfree MB, Graves JA. Absence of SOX3 in the developing marsupial gonad is not consistent with a conserved role in mammalian sex determination. Genesis. 2000;27:145–52.

Sutton E, Hughes J, White S, Sekido R, Tan J, Arboleda V, Rogers N, Knower K, Rowley L, Eyre H, et al. Identification of SOX3 as an XX male sex reversal gene in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:328–41.

Ross DG, Bowles J, Koopman P, Lehnert S. New insights into SRY regulation through identification of 5′ conserved sequences. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:85.

Bagheri-Fam S, Sinclair AH, Koopman P, Harley VR. Conserved regulatory modules in the Sox9 testis-specific enhancer predict roles for SOX, TCF/LEF, Forkhead, DMRT, and GATA proteins in vertebrate sex determination. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:472–7.

Li WH. Molecular Evolution. Stamford: Sinauer Associates; 1997.

O'Neill RJ, Eldridge MD, Crozier RH, Graves JA. Low levels of sequence divergence in rock wallabies (Petrogale) suggest a lack of positive directional selection in SRY. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:350–3.

O'Neill RJ, Brennan FE, Delbridge ML, Crozier RH, Graves JA. De novo insertion of an intron into the mammalian sex determining gene. SRY Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1653–7.

Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, Hutchison CA, Slocombe PM, Smith M. Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA. Nature. 1977;265:687–95.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–82.

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–9.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25.

Rzhetsky A, Nei M. Statistical properties of the ordinary least-squares, generalized least-squares, and minimum-evolution methods of phylogenetic inference. J Mol Evol. 1992;35:367–75.

Sourdis J, Nei M. Relative efficiencies of the maximum parsimony and distance-matrix methods in obtaining the correct phylogenetic tree. Mol Biol Evol. 1988;5:298–311.

Kishino H, Hasegawa M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:170–9.

Felsenstein J. Mathematics vs. evolution: mathematical evolutionary theory. Science. 1989;246:941–2.

Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–91.

Quandt K, Frech K, Karas H, Wingender E, Werner T. MatInd and MatInspector: new fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4878–84.

Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–90.

Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Swails J, Götz AW, Kolossváry I, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Wolf RM, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh M-J, Cui G, Roe DR, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Salomon-Ferrer R, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman PA. AMBER 12. San Francisco: University of California; 2012. Accessed 31 July 2012

Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–92.

Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LGA. Smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–93.

Li DW, Brüschweiler R. NMR-based protein potentials. Angew Chem. 2010;122:6930–2.

Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2010;78:1950–8.

Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–35.

Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–41.

Miyamoto S, Kollman PA. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:952–62.

Chong LT, Duan Y, Wang L, Massova I, Kollman PA. Molecular dynamics and free-energy calculations applied to affinity maturation in antibody 48G7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14330–5.

Huo S, Massova I, Kollman PA. Computational alanine scanning of the 1:1 human growth hormone–receptor complex. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:15–27.

Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, Lee M, Lee T, Duan Y, Wang W, et al. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:889–97.

Srinivasan J, Cheatham TE, Cieplak P, Kollman PA, Case DA. Continuum solvent studies of the stability of DNA, RNA, and Phosphoramidate−DNA helices. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9401–9.

Gilson MK, Zhou HX. Calculation of protein-ligand binding affinities. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:21–42.

Honig B, Nicholls A. Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science. 1995;268:1144–9.

Harley VR, Clarkson MJ, Argentaro A. The molecular action and regulation of the testis-determining factors, SRY (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) and SOX9 [SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG) box 9]. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:466–87.

McDowall S, Argentaro A, Ranganathan S, Weller P, Mertin S, Mansour S, Tolmie J, Harley V. Functional and structural studies of wild type SOX9 and mutations causing campomelic dysplasia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24023–30.

Whitworth DJ, Pask AJ, Shaw G, Marshall Graves JA, Behringer RR, Renfree MB. Characterization of steroidogenic factor 1 during sexual differentiation in a marsupial. Gene. 2001;277:209–19.

Pask AJ, Harry JL, Graves JA, O'Neill RJ, Layfield SL, Shaw G, Renfree MB. SOX9 has both conserved and novel roles in marsupial sexual differentiation. Genesis. 2002;33:131–9.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful Dr. Naoyuki Takahata for his critical comments from the beginning of this research project, Ms. Kaori Kuno for her technical support, Dr. Mineyo Iwase and the staffs at Kanazawa Zoo in Yokohama for marsupial samples, and the RIKEN Integrated Cluster for the computational resources. The tammar wallaby genome DNA was a kind gift from Dr. Paul Waters. We also thank Drs. Jenifer Graves, Marilyn Renfree, Makoto Ono, Makoto Taiji and Atsushi Suenaga for their constructive discussion at the early stage.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; Wakate (B) 24770225 to Y.K., Yamada Science Foundation; long-term dispatch assistance (2013) to Y.K., The Japan Science Society; Sasakawa science research grant (24–429) to Y.K., Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Postdoctoral fellowship for Research Abroad (24177) to Y.K., and CREST, JST (JPMJCR14M3) to H.X. K.

Availability of data and materials

DNA sequence data that was generated for this study has been deposited into GenBank (accession numbers: LC111530; LC111531; LC111532).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK and VH designed the experiment; YK and JR performed the experiment; YK, HXK and YS analyzed and interpreted the data; YK, HXK, JR, VH and YS wrote the paper. All co-authors participated in the scientific discussions and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The functionally important amino acid residues and substitutions in SRY. Table S2. The pair of proteins and DNA used for the molecular dynamics analysis. Table S3. The list of amino acid residues interacting with DNA. Table S4. The values of the binding energy of protein and DNA. (XLSX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Katsura, Y., Kondo, H.X., Ryan, J. et al. The evolutionary process of mammalian sex determination genes focusing on marsupial SRYs. BMC Evol Biol 18, 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1119-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1119-z