Abstract

Background

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is abundant in the aquatic environment particularly in warmer waters and is the leading cause of seafood borne gastroenteritis worldwide. Prior to 1995, numerous V. parahaemolyticus serogroups were associated with disease, however, in that year an O3:K6 serogroup emerged in Southeast Asia causing large outbreaks and rapid hospitalizations. This new highly virulent strain is now globally disseminated.

Results

We performed a four-way BLAST analysis on the genome sequence of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, an O3:K6 isolate from Japan recovered in 1996, versus the genomes of four published Vibrio species and constructed genome BLAST atlases. We identified 24 regions, gaps in the genome atlas, of greater than 10 kb that were unique to RIMD2210633. These 24 regions included an integron, f237 phage, 2 type III secretion systems (T3SS), a type VI secretion system (T6SS) and 7 Vibrio parahaemolyticus genomic islands (VPaI-1 to VPaI-7). Comparative genomic analysis of our fifth genome, V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810, an O3:K6 isolate recovered in 1983, identified four regions unique to each V. parahaemolyticus strain. Interestingly, AQ3810 did not encode 8 of the 24 regions unique to RMID, including a T6SS, which suggests an additional virulence mechanism in RIMD2210633. The distribution of only the VPaI regions was highly variable among a collection of 42 isolates and phylogenetic analysis of these isolates show that these regions are confined to a pathogenic clade.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is considerable genomic flux in this species and that the new highly virulent clone arose from an O3:K6 isolate that acquired at least seven novel regions, which included both a T3SS and a T6SS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Gram-negative halophilic, aerobic bacterium that is distributed in marine and estuarine environments worldwide [1]. In the 1950s, Fujino demonstrated that V. parahaemolyticus was the etiological agent responsible for a gastroenteritis outbreak in Osaka, Japan. Presently, in Taiwan, Japan and other South East Asian countries, V. parahaemolyticus cause over half of all food poisoning outbreaks of bacterial origin [2, 3]. Baross and Liston in the late 1960s identified V. parahaemolyticus in seawater, sediments and shellfish in the United States [4, 5]. Today, V. parahaemolyticus is the leading cause of seafood-associated bacterial gastroenteritis in the United States. V. parahaemolyticus can also cause serious wound infections resulting in necrotizing fasciitis when wounds are exposed to V. parahaemolyticus contaminated water [6–8]. Although less common, V. parahaemolyticus can cause fatal septicemia in immune compromised hosts [6, 7]. Most isolates of V. parahaemolyticus are non-pathogenic and only a small number can cause infections in humans [1]. Clinical isolates of V. parahaemolyticus produce beta type hemolysis on blood agar (Wagatsuma agar) called the Kanagawa-phenomenon (KP), which is linked to the production of a thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) [9–11]. TDH damages eukaryotic cells by acting as a pore forming toxin that alters the ion balance of cells [12]. The presence of the tdh gene, which encodes TDH is often used as a diagnostic tool to identify pathogenic isolates of V. parahaemolyticus. Five sequence variants of tdh (named tdh1 to tdh5) have been identified, however only tdh2 appears to have a high-level of transcription [13, 14]. In the 1980s, several cases of gastroenteritis caused by hemolytic KP-negative TDH-negative V. parahaemolyticus isolates were reported [11]. These isolates contained a TDH-related hemolysin (TRH) encoded by trh, which showed 69% sequence similarity with tdh [11]. TDH and TRH are considered the main virulence factors of V. parahaemolyticus and strains can contain either TDH or TRH or both [15–19]. Although isolates that do not contain tdh or those that have a deletion in tdh are still cytotoxic to cells. Hence, the overall mechanism involved in the organism's pathogenesis remains unclear.

Analysis of the complete genome sequence of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, a clinical isolate recovered in Japan in 1996, identified a type III secretion system (T3SS) on each chromosome designated T3SS-1 and T3SS-2 [20]. Subsequently, the functional significance of both T3SSs was determined using deletion mutants [21]. The T3SS-1 deletion mutants had significantly decreased cytotoxic activity compared with that of the wild type [21]. The T3SS-2 deletion mutants showed diminished intestinal fluid accumulation, in an enterotoxicity assay using the rabbit ileal loop test, whereas T3SS-1 mutants were similar to the wild type [21]. In addition, a number of effector proteins for these T3SSs have been identified [22–24]. T3SS-1 is present in both clinical and environmental isolates and has a percent G+C content similar to the rest of the genome indicating that this region is ancestral to the species [20]. Henke and Bassler [25] found that unlike other T3SSs in pathogenic E. coli, which are activated by quorum sensing, T3SS-1 in V. parahaemolyticus is repressed at high cell densities.

Associated with T3SS-2 encoded on chromosome 2 are Tdh1 and Tdh2, as well as a cytotoxic necrotizing factor, an exoenzyme T, and at least five transposases [20]. The presence of transposases and a G+C content of 40% (less than the overall genome), suggests that T3SS-2 may be a integrative element similar to pathogenicity islands identified in pathogenic E. coli, S. enterica, and V. cholerae, which we named Vibrio parahaemolyticus island-7 (VPaI-7) [20, 26]. T3SS-2 is present predominantly in the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 highly virulent strains recovered after 1995, whereas most clinical isolates recovered before 1995 do not encode T3SS-2 indicating that the region is not essential for virulence, but may enhance virulence when present [20].

Serotyping of V. parahaemolyticus isolates has identified more than 13 O antigen groups and 71 K antigen types [27]. Up until 1995, V. parahaemolyticus associated gastroenteritis was caused by many different serogroups, although in some geographic regions specific serogroups predominated. For example, in the United States a predominance of the O4 serogroup among clinical isolates was apparent [28–32]. In 1995, an outbreak of V. parahaemolyticus infections occurred in Calcutta, India, which caused rapid hospitalization of those infected and were caused by a single serotype, a new O3:K6 highly virulent strain [33]. Since 1995, a global dissemination of this V. parahaemolyticus new highly virulent strain is evident since it has now been isolated throughout Asia, America, Africa, and Europe [3, 29, 34–40]. For example, in 1998, the new highly virulent strain was responsible for a large outbreak of gastroenteritis in Galveston Bay, Texas [29]. Later on that year, the highly virulent strain was responsible for large gastroenteritis outbreaks in Long Island Sound-Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey [41]. In 2005, the highly virulent strain caused a major outbreak in Chile with over 1,000 cases [3]. Non-O3:K6 pathogenic isolates recovered since 1995, including O4:K68, O1:KUT, and O1:K25 serotypes, have been shown to be closely related to the new highly virulent O3:K6 strain based on molecular typing schemes and phylogenetic approaches [29, 30, 37–39, 42–44].

Previously, it was thought that V. parahaemolyticus was confined to tropical climates, however recent studies report the recovery of O3:K6 isolates from the water in Southern Chile and Alaska, that up until now were considered too cold to support the growth of this organism [35, 45, 46]. These recent discoveries suggest a change in the organism's ability to adapt and survive in colder environments. Indeed the ability of V. parahaemolyticus to survive and proliferates in its environmental niches, in shellfish and in the human intestine may have resulted from the acquisition of regions encoding novel traits which are differentially regulated in different niches. Additionally, the spread of the organism is another indication of global warming, which is likely to play a role in increasing V. parahaemolyticus distribution and occurrence.

First, we used a two step genomic approach to elucidate the genomic changes that may have resulted in the emergence of the new highly virulent O3:K6 and related strains. We performed in silico whole genome comparisons of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 versus the genome sequences of V. cholerae N16961, V. vulnificus YJ016 and CMCP6, and V. fischeri ES114. We constructed genome BLAST atlases of each species to determine regions unique to V. parahaemolyticus. We uncovered 24 regions greater than 10 kb that were unique to RIMD2210633 and absent from the other Vibrio species examined. These included functionally distinct regions such as the class 1 integron, f237-like phages, Vibrio parahaemolyticus genomic island regions (VPaI-1 to VPaI-7), a lipopolysaccaride (LPS)/capsule polysaccharide (CPS) region, two osmotic stress response clusters, two T3SSs and a T6SS. Next, we compared the RIMD2210633 genome sequence to that of AQ3810, an O3:K6 strain isolated in 1983, to elucidate the steps involved in the emergence of the globally disseminated O3:K6 highly virulent strain. This analysis identified several regions unique to one isolate or the other. Molecular analysis of the distribution of regions unique to RIMD2210633 among 42 natural isolates revealed that only regions encoding integrase or transposase genes (7 island regions) were variably present. We reconstructed the phylogeny of the 42 isolates based on multilocus sequence analysis, and mapped the distribution of the 7 island regions, which showed that these regions were acquired by the new O3:K6 highly virulent strain and predominant in one clade.

Results and Discussion

Comparative genome analysis of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 versus V. cholerae N16961, V. vulnificus YJ016 and CMCP6, and V. fischeriES114

Systematic BLAST analysis was carried out for each of the ORFs of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 compared with each of the ORFs from the genome sequences of V. cholerae N16961, V. vulnificus YJ016 and CMCP6, and V. fischeri ES114. This four-way BLAST analysis was used to construct genome BLAST atlases of chromosome 1 and 2 of the four Vibrio species with V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as a reference (Fig. 1). The four outer circles of solid color represent conserved proteins of the BLASTed genomes for both chromosome 1 and 2. The outer most circle represents the V. fischeri ES114 genome (purple circle), the next two circles represents V. vulnificus YJ016 and CMCP6 (navy and green circles), followed by the fourth circle (brown circle), which represents V. cholerae N16961. The innermost circles show DNA structure features, repeat sequences and base composition properties of the reference V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 (Fig. 1). It is of interest to note that chromosome 1 shows a higher level of overall conservation among the species examined than chromosome 2 indicating that a lot of species specific genes lie on chromosome 2. There are approximately 44 gap regions (greater than 1 kb) on chromosome 1 and 29 gap regions (greater than 1 kb) on chromosome 2, common to all four outer circles and these gaps represent regions of the V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 chromosomes that are unique being absent from all other isolates examined. Differences in these regions in their DNA structural features such as intrinsic curvature, stacking energy and position preference correlate with some of the gap regions and represent phages, integrons and genomic islands, that is signatures of foreign DNA acquired by horizontal transfer (Fig. 1).

Genome BLAST Atlas of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus V. fischeri ES114 (outer most circle purple), V. vulnificus strains YJ016 and CMCP6 (2nd navy and 3rd green circles) and V. cholerae N16961 (4th circle brown) for chromosome 1 (a) and chromosome 2 (b)[60]. The gaps or holes in the outer four circles represent regions present in V. parahaemolyticus strain RIMD2210633 that are absent from the other three species. The innermost circles show DNA structure features, DNA intrinsic curvature (circle 5), DNA stacking energy (circle 6), DNA position preference (circle 7), positive and negative coding strands are indicated by dark blue and red circle. Global direct and global inverted repeats are represented by circles 9 and 10, respectively and the two inner most circles represent GC shew and AT content, respectively.

Of the 73 gap regions, our analysis uncovered 24 regions greater than 10 kb that are present in RIMD2210633 and absent from the other species examined, that is the gap regions in the four outer circles in Figure 1 (Table 1). Of the 24 regions identified, 11 regions encoded an integrase or transposase, 9 regions had aberrant GC content (45 ± 3%), 7 regions of which had lower G+C content compared to the rest of the genome suggesting that these regions were acquired by horizontal gene transfer (Table 1). The 24 regions included 14 previously identified: lipopolysaccharide and capsule polysaccharide gene clusters, a class 1 integron, 2 f237 phage regions, 2 osmotic stress response gene clusters, 2 T3SSs, and the Vibrio parahaemolyticus island (VPaI) regions (Table 1) [20, 26, 47]. The 10 additional regions unique to V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 included 2 regions encoded on chromosome 1 and 8 regions encoded on chromosome 2 (Table 1). On chromosome 1, region VP0081 to VP0092 encodes mainly hypothetical proteins of unknown function; VP0081 encodes a homologue of a hyper osmotic shock protection protein. Region VP1386 to VP1420 encodes hemo utilization/adhesion proteins, OmpA, a ClpA/B type protease, a BfdA homologue, a putative IcmF-related protein and related type VI secretion system (T6SS) proteins (VP1401 to VP1409), which is predicted to be involved in intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport in other Gram-negative pathogens. On chromosome 2, region VPA0434 to VPA0458 encodes a large number of homologues of genes involved in degradation processes. Region VPA887 to VPA0914 encode proteins that show homology to phage f237 on chromosome 1. Within region VPA0950 to VPA0962 are homologues of biofilm associated proteins among others. Region VPA0989 to VPA0999 contains homologues of a number of peptidase, lipase and amylase genes, and region VPA1440 to VPA1444 encode a type I secretion system (Table 1). Region VPA1503 to VPA1513 contained a type 1 pilin homologue similar to Pap pilin identified in Burkholderia pseudomallie, Pseudomonas spp and Yersinia spp. Region VPA1559 to VPA1583 encodes a number of proteins with a possible role in antibiotic resistance and region VPA1652 to VPA1679 contains a ferric uptake system.

We also constructed genome BLAST atlases of all 28 genomes available for members of the family Vibrionaceae in the database, this included eight additional species of the Vibrionaceae family. V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810, V. cholerae 1587, AM-19226, MAK757, MO10, MZO-2, MZO-3, B33, NCTC8457, RC385, O395, V51, V52, 623–39, and 2740–80, V. harveyi ATCC BAA116, V. alginolyticus 12G01, Vibrio sp. Ex25, V. vulnificus CMCP6 and YJ016, V. splendidus 12B01, Vibrio sp. MED222, V. fischeri ES114, V. salmonicida LF1238, V. angustum S14, P. profundum SS9 and 3TCK for chromosome 1 (a) and chromosome 2 (b), in which each gap region can be zoomed in on to examine in detail (see Additional file 1 &2) [48].

Most of the 24 gap regions remained unique to V. parahaemolyticus, exceptions were noted (see Additional file 1 and 2). For example, on chromosome 1 region VP0081 to VP0092 is present in V. alginolyticus 12G01 and Vibrio sp. Ex25, the osmotolerance gene clusters are partially present in V. alginolyticus 12G01, V. harveyi ATCC BAA116 and Vibrio sp. Ex25, and the T3SS-1 and T6SS (VP1388 to VP1414) are present in V. alginolyticus, V. harveyi and Vibrio sp. Ex25 (see Additional file 1 and 2). On chromosome 2, region VPA0950 to VPA0962 was present in Vibrio sp. Ex25, homology to VPaI-7 within the T3SS-2 region (VPA1332 to VPA1355 and VPA1358 to VPA1370) is present in V. cholerae strains 1587, AM-19226, V51 and 623–39. Region VPA1440 to VPA1442 is present in Vibrio sp. Ex25. Region VPA1503 to VPA1521, which encodes a type I pilin is present in V. alginolyticus, V. harveyi and Vibrio sp. Ex25 (see Additional file 1 and 2).

Genome sequence of V. parahaemolyticusAQ3810

The previously published V. parahaemolyticus genome sequence is from RIMD2210633 a tdh positive, trh and urease negative O3:K6 clinical isolate of the highly virulent clone recovered in Japan in 1996. In order to unravel events at the genome level that may have lead to the emergence and dissemination of the new highly virulent strain, we sequenced the genome of AQ3810, a tdh positive, trh and urease negative O3:K6 isolate recovered in Japan in 1983 for comparison. The complete genome sequence of AQ3810 is 5.8 Mb and 5509 proteins have been annotated within its genome compared with the 5.2 Mb genome of RIMD2210633, which has 4832 annotated proteins. There is extensive sequence homology between the two sequences, however genomic differences were noted. As had been found within other Vibrio species, the gene capture system, the -integron encoded in RIMD2210633 and AQ3810 do not share any significant sequence similarity.

We examined the genome of AQ3810 for the presence of the 24 regions identified as unique to RIMD2210633 from our species comparisons (Table 1). Of the 24 regions, 8 regions were absent from AQ3810, 5 genomic islands (VPa-1, VPaI-2, VPaI-4, VPaI-5 and VPaI-6), ORFs VP1386 to VP1420, which encodes T6SS, the class 1 integron, and phage f237 encoded on chromosome 1 (Table 1). These data confirm our previous result that VPaI-1, VPaI-4, VPaI-5 and VPaI-6 are unique to the new highly virulent strain recovered after 1995 [26]. For example, two of the missing regions, VPaI-1 and VPaI-4, integrate at a tRNA-met (VP0404.1) and tRNA-ser locus (VP2130.1), respectively in RIMD2210633, however, in AQ3810, both of these tRNA sites are empty (see Additional file 3). The other two missing regions VPaI-5 and VPaI-6 regions are located between core chromosomal ORFs VP2889 and VP2911, and VPA1252 and VPA1271, respectively in RIMD2210633, while in AQ3810, the homologues of these genes are contiguous indicating that these sites are empty (see Additional file 3).

Two VPaIs were rearranged. One, the VPaI-2 region (VP0634 to VP0643), is present at the tmRNA gene (ssrA) in RIMD2210633, a gene that encodes both tRNA and mRNA properties. In AQ3810, at this same locus, the first three genes of this region are present (VP0634 to VP0636), which encode homologues of a nitrilase/cyanide hydratase, OmpA and LysR, but the remaining genes are replaced by a novel region encoding an integrase (see Additional file 4). A second island region, VPaI-3 (VP1071 to VP1095) present at a second tRNA-ser locus (VP1070.1) in both RIMD2210633 and AQ3810 has 21 genes in common (ORFs VP1074 to VP1095) and 6 genes, two novel integrases and four hypothetical proteins, are adjacent to the tRNA-ser locus in AQ3810 (see Additional file 4).

Two additional regions named VPaI-8 and VPaI-9 were identified in AQ3810 (see Additional file 4). VPaI-8 is a 17 kb region located between homologues of VP3057 and VP3058 and contains ORFs A79_5175 to A79_5191, which encode a number of hypothetical proteins, homologues of SMF and KAP proteins, and two integrases separated by a single ORF (see Additional file 4). VPaI-9 is a 22 kb region integrated between homologues of VP0006 and VP0007. VPaI-9 encodes an integrase, an excisionase, a helicase and a type I restriction modification system.

ORFs VP1386 to VP1420 are absent from AQ3810. This regions encodes T6SS (ORFs VP1401 to VP1409) and a range of proteins that could be translocated by this system; hemo utilization/adhesion proteins, OmpA, a ClpA/B type protease, a BfdA homologue, a putative IcmF-related protein. This suggests the presence of an additional virulence mechanism in the highly virulent O3:K6 clone. T6SSs have been identified in a range of Gram-negative pathogens including pathogenic V. cholerae and in that species T6SS translocates a bacterial host protein into host cells that cross link actin [49].

Distribution of VPaI-2, VPaI-3 and VPaI-7

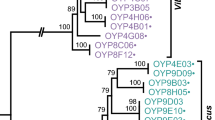

Previously, we examined the distribution of VPaI-1, VPaI-4, VPaI-5 and VPaI-6 among a worldwide collection of V. parahaemolyticus isolates and found that these regions are unique to 24 isolates of the highly virulent O3:K6 clone [26]. We determined the distribution of VPaI-2, VPaI-3 and VPaI-7 using primer pairs described in Table 2. Of the 42 V. parahaemolyticus isolates examined by PCR assays using two primer pairs encompassingVPaI-2, 27 isolates gave positive PCR bands. These isolates were recovered post-1995 and include the 24 isolates that were previously shown to contain VPaI-1, VPaI-4 to -6 (Fig. 2). VPaI-2 was also present in isolates UCMV586 and 1324, O8:K22 and O4:K6 isolates recovered after 1995, and ATCC43996, an O3:K4 clinical isolate from recovered in the UK in 1970 (Fig. 2). The presence of VPaI-2 in ATCC43996 indicates that this region was present in isolates before 1995, prior to its acquisition by the new highly virulent strain. VPaI-2 encodes an integrase, a resolvase, hypothetical proteins, a ribonuclease HI, an aminohydrolase, transcriptional regulators and a lipase.

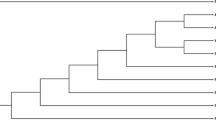

Evolutionary relationships of V. parahaemolyticus isolates based on the concatenated housekeeping gene tree. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method based on the based on Kimura 2-parameter distance using MEGA-3. The plus and minus signs represent the presence and absence of VPaIs among our collection of isolates.

Molecular analysis of the distribution of VPaI-3 found that the region is present in 25 V. parahaemolyticus isolates, which included the same set of isolates that contain VPaI-1, VPaI-2, and VPaI-4 to VPaI-6 (O3:K6 and related isolates recovered after 1995) (Fig. 2). One exception was noted, KE10462, an O3:K6 isolate recovered in Japan in 1986. In addition, in two O3:K6 pre-1995 isolates, KE9967 and U-5474, the VPaI-3 region was found to be partially present, suggesting that this region is unstable and has been deleted from these isolates. VPaI-3 contains several transcriptional regulators, hypothetical proteins and a methyl accepting chemotaxis protein.

VPaI-7, an 81 kb region present on chromosome 2, encodes T3SS-2, two copies of the tdh gene, a cytotoxic necrotizing factor, an exoenzyme T gene and five transposase genes [20]. T3SS-2 in V. parahaemolyticus showed similarity to a T3SS present in several pathogenic V. cholerae non-O1 and non-O139 isolates [50, 51]. To determine the distribution of VPaI-7, we used 12 primer pairs spanning the 81 kb region (Table 2). Of the 42 V. parahaemolyticus isolates examined, 30 isolates were found to contain the entire VPaI-7 region. Similar to the VPaI-2 and VPaI-3 regions, the 30 VPaI-7-positive isolates included all 24 highly virulent isolates as well as 3 O3:K6 strains isolated pre-1995, strains KE9967, U-5474, and ATCC43996 (Fig. 2). The region was present in three O4 serogroup isolates, 1324, an O4:K6, and two Spanish isolates, 30824 and 428/00 (Fig. 2). Although, T3SS-2 was previously reported to be present only in the highly virulent strain, this appears not to be the case as others have found [52]. This region was partially present in 6 isolates (Fig. 2). A primer pair designed within VPA1308/VPA1309, and a primer pair within and VPA1400/VPA1401 all gave a positive PCR product with all strains examined indicating that these genes represent core chromosomal flanking genes.

We examined 11 additional regions that were unique to V. parahaemolyticus for their distribution among our collection of isolates, all 11 regions were present in all the highly virulent isolates, in fact 3 regions were present in all strains examined (see Additional file 5). Five regions were absent from 1 to 3 isolates, which included the region that encodes T6SS that is absent from two pre-1995 O3:K6 strains. Three regions were absent from five isolates (see Additional file 5).

Evolutionary genetic relationships

To understand the evolutionary significance of the distribution of the VPaI regions among our collection of isolates, a phylogenetic frame work was constructed by multilocus sequence (MLS) analysis of an initial analysis of three housekeeping genes. MLS analysis was demonstrated in numerous studies to be a powerful method to both discriminate and determine the phylogenetic relationships among bacterial isolates including Vibrio species [53–55]. We found similar to others that V. parahaemolyticus isolates are highly related sharing substantial sequence similarity at the three loci we examined [37, 42] (Fig. 2). Within the 1854 bps examined among the 42 isolates, there were a total of 39 polymorphic sites of which 21 sites were phylogenetically informative and 12 sequence types (ST) were found. For the purposes of this study, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method using Kimura 2-parameter, which clustered the strains into two closely related but distinct groups named A and B (Fig. 2). The first group contains all highly virulent isolates whereas group B is comprised of mainly environmental isolates recovered in Spain in the early 2000s. Within group A are 25 isolates that are identical at all three loci examined; these isolates include 22 O3:K6 isolates with worldwide distribution recovered pre-1995 and post-1995, and 3 O1 serogroup isolates (O1:K25 and O1:KUT) recovered post-1995. O3:K6 and O1:K25 isolates recovered post-1995, and O3:K6 isolates recovered pre-1995 shared identical sequence profiles (Fig. 2). These data support the hypothesis that O1:K25 and O1:KUT serogroups arose from the O3:K6 highly virulent strain by acquisition of novel O and K antigens similar to the emergence of the pathogenic V. cholerae O139 serogroup strain from an O1 El Tor isolate. Acquisition of novel O and K antigens would be evolutionary advantageous since it may play a role in host immune avoidance in V. parahaemolyticus infection. Clustering with these O3:K6, O1:K25, O1:KUT isolates are four identical O4 serogroup isolates and KE10464, a divergent O3:K6 pre-1995 (Fig. 2). Thus, it appears that acquisition of novel O antigens is frequent in this species and more recent data suggests this is an ongoing event [3]. Also found within group A are several divergent O3:K6 pre-1995 and post-1995 isolates, and a single divergent O4:K8 post-1995, 1324 (Fig. 2). Group B consists of 5 isolates, with various serotype designations but all were recovered in Spain post-1995 (Fig. 2). Three of the strains were recovered from mollusks and sea sediment, and two strains 30824 and 428/00, which shared an identical ST, were from clinical sources. Overall, the phylogenetic tree constructed from concatenated sequences of three housekeeping genes indicates that pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus isolates are highly homologous as others have previously shown [42].

We mapped the distribution of each of the VPaI genomic islands onto the phylogenetic tree to elucidate the possible steps involved in the emergence of the globally distributed V. parahaemolyticus new highly virulent strain. We found that similar to VPaI-1, VPaI-4, VPaI-5 and VPaI-6, VPaI-2 and VPaI-3 are predominately present among the highly virulent isolates recovered after 1995 with only one exception noted for VPaI-2, strain ATCC43996 recovered in the UK in 1970, an O3:K4 serogroup (Fig. 2). The VPaI-3 region was present in two pre-1995 O3:K6 isolates, KE9967 and U5474 that have an identical sequence type, and in KE10462, which shows an identical sequence type to five additional pre-1995 and 16 post-1995 O3:K6 isolates. KE10462 also appears to have contained the VPaI-7 regions since it is partially present in this isolate (Fig. 2). KE10462 has been shown to be positive for group specific PCR (GS-PCR), which is based on the toxRS nucleotide sequence, that has previously been shown to differentiate post-1995 pandemic strains from non-pandemic and pre-1995 isolates [26, 39].

In conclusion, the most parsimonious scenario for the evolution of the new highly virulent O3:K6 clone suggests that a pre-1995 O3:K6 strain obtained regions VPaI-1 to VPI-7, and a T6SS encoded within ORFs VP1386–VP1420, this secretion systems along with T3SS-2 may explain the highly virulent nature of the O3:K6 virulent clone. It appears that V. parahaemolyticus isolates have the ability to acquire large regions of DNA and that this is an ongoing process among pathogenic isolates. For example, the O1 and K antigens, which are encoded in the same genomic region, are undergoing frequent change among closely related strains and this may be a mechanism to avoid the host immune system.

The possible origins of the V. parahaemolyticus variable regions appear to be quite diverse. Blast analysis of the VPaI-1 encoded proteins found 7 ORFs highly homologous to a 22 Kb island present in V. cholerae strain 623–39 at the same tRNA-met insertion site, whereas a similar analysis of VPaI-3 showed high sequence similarity to a region in V. harveyi HY01 (AIQ_705 to AIQ_762). VPaI-2 encoded several ORFs with high similarity to ORFs identified in Vibrio sp Ex25. Most of VPaI-5 showed homology to ORFs from Shewanella woodyi and Shewanella sp, and similarly several ORFs of VPaI-6 were homologous to a region in Shewanella sp ANA-3. The T3SS-2 region encoded on island VPaI-2 is most closely related to a T3SS recently identified in V. cholerae V51, a non-O1 serogroup isolate [56]. Region VP1386 to VP1420, which encodes a T6SS as well as a Rhs element, showed extensive homology to a region in V. harveyi ATCC BAA-1116.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 42 V. parahaemolyticus isolates were examined in this study as previously described [26]. The 42 isolates were temporally (1970 to 2003) and geographically widespread (Asia, Europe and South America) and encompassed 10 different serotypes. All V. parahaemolyticus isolates were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) supplemented with 3% NaCl and stored at -70°C in LB broth with 20% (v/v) glycerol.

Comparative bioinformatics analysis

We performed four-way BLAST analysis of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, an O3:K6 isolated in 1996, versus V. vulnificus YJ016, V. vulnificus CMCP6, V. cholerae N16961 and V. fischeri ES114 to identify regions that were unique to V. parahaemolyticus. Complete nucleotide sequences and annotations for the V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633, V. vulnificus YJ016, V. vulnificus CMCP6, V. cholerae N16961 and V. fischeri ES114 were retrieved and downloaded from NCBI [20, 57–59]. These were used to construct a genome atlas of the complete genome sequence of all five isolates. The genome atlas plot maps DNA structure features, repeats, and base composition properties of V. parahaemolyticus as well as each gene present in RIMD2210633, and their homologues in all four additional species oriented at the ori[60]. In addition, we constructed a zoomable genome atlas of the complete genome sequences of all 27 members of the family Vibrionaceae available in the database. This data can be interactively examined for chromosome 1 and for chromosome 2 on the web [48]. We compared the genome of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 to the genome of V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810, an O3:K6 isolated in 1983, using the Artemis comparison tool (ACT) program [61].

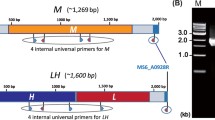

Molecular analysis

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from each V. parahaemolyticus isolate using the G-nome DNA isolation kit from Bio 101. To determine the distribution of regions unique to V. parahaemolyticus among our collection of 41 isolates, PCR assays were performed. Primer pairs were designed to target within the regions of interest as well as flanking the regions (Table 2). PCR was performed in a 25 μl reaction mixture with the following cycles: an initial denaturation step at 96°C for 3 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, 30s of primer pair annealing at the respective temperature, an extension step at 72°C for 1–4 min (depending on expected PCR product size). PCR primers to amplify three chromosomal housekeeping genes, gyrase subunit B (gyrB, VP0014), malate dehydrogenase (mdh, VP0325), and chaperonin (groEL-1, VP2851), were designed based on the sequence of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 (Table 1). The housekeeping genes were PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA isolated from all V. parahaemolyticus isolates and PCR products were purified using Jetquick PCR purification Kit (GENOMED). The mdh, gyrB and groEL-1 sequences were determined by MWG-Biotech based on the dye deoxy terminator method and the reaction products were separated and detected on an ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer.

Phylogenetic analysis

The multiple sequence alignment program ClustalW was used to align nucleotide sequences for each housekeeping gene [62]. Rates of synonymous substitutions/synonymous site (K S ) were calculated by the methods of Nei and Gojobori and Nei and Lin [63, 64]. To analyze the evolutionary relationships among V. parahaemolyticus isolates, the concatenated sequence of all three housekeeping genes was used to construct a Neighbour-Joining phylogenetic tree based on Kimura 2-parameter distance using MEGA-3 [65].

Nucleotide sequence accession no

The sequences of mdh, gyrB and groEL-1 were submitted to GenBank and given the accession numbers GenBank EU629305–EU629345.

Abbreviations

- T3SS:

-

type III secretion systems

- T6SS:

-

type VI secretion system

- VPaI:

-

Vibrio parahaemolyticus genomic islands

- TDH:

-

thermostable direct hemolysin

- KP:

-

Kanagawa-phenomenon

- TRH:

-

TDH-related hemolysin

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccaride

- CPS:

-

capsule polysaccharide (CPS).

References

Joseph SW, Colwell RR, Kaper JB: Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related halophilic Vibrios. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1982, 10 (1): 77-124. 10.3109/10408418209113506.

Pan TM, Wang TK, Lee CL, Chien SW, Horng CB: Food-borne disease outbreaks due to bacteria in Taiwan, 1986 to 1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35 (5): 1260-1262.

Nair GB, Ramamurthy T, Bhattacharya SK, Dutta B, Takeda Y, Sack DA: Global dissemination of Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype O3:K6 and its serovariants. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007, 20: 39-48. 10.1128/CMR.00025-06.

Baross J, Liston J: Isolation of vibrio parahaemolyticus from the Northwest Pacific. Nature. 1968, 217 (5135): 1263-1264. 10.1038/2171263a0.

Baross J, Liston J: Occurrence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related hemolytic vibrios in marine environments of Washington State. Appl Microbiol. 1970, 20 (2): 179-186.

Daniels NA, MacKinnon L, Bishop R, Altekruse S, Ray B, Hammond RM, Thompson S, Wilson S, Bean NH, Griffin PM, Slutsker L: Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973-1998. J Infect Dis. 2000, 181 (5): 1661-1666. 10.1086/315459.

Daniels NA, Ray B, Easton A, Marano N, Kahn E, McShan AL, Del Rosario L, Baldwin T, Kingsley MA, Puhr ND, Wells JG, Angulo FJ: Emergence of a new Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype in raw oysters: A prevention quandary. Jama. 2000, 284 (12): 1541-1545. 10.1001/jama.284.12.1541.

Ralph A, Currie BJ: Vibrio vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus necrotising fasciitis in fishermen visiting an estuarine tropical northern Australian location. J Infect. 2007, 54 (3): e111-4. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.06.015.

Nishibuchi M, Kaper JB: Nucleotide sequence of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 1985, 162 (2): 558-564.

Nishibuchi M, Kumagai K, Kaper JB: Contribution of the tdh1 gene of Kanagawa phenomenon-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus to production of extracellular thermostable direct hemolysin. Microb Pathog. 1991, 11 (6): 453-460. 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90042-9.

Nishibuchi M, Fasano A, Russell RG, Kaper JB: Enterotoxigenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus with and without genes encoding thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1992, 60: 3539-3545.

Honda T, Ni Y, Miwatani T, Adachi T, Kim J: The thermostable direct hemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a pore-forming toxin. Can J Microbiol. 1992, 38 (11): 1175-1180.

Nishibuchi M, Kaper JB: Duplication and variation of the thermostable direct haemolysin (tdh) gene in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Mol Microbiol. 1990, 4 (1): 87-99. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02017.x.

Nakaguchi Y, Nishibuchi M: The promoter region rather than its downstream inverted repeat sequence is responsible for low-level transcription of the thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin (trh) gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187 (5): 1849-1855. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1849-1855.2005.

Honda T, Iida T: The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct heamolysin and related heamolysins. Rev Med Microbiol. 1993, 4: 106-113.

Honda T, Ni YX, Miwatani T: Purification and characterization of a hemolysin produced by a clinical isolate of Kanagawa phenomenon-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related to the thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1988, 56 (4): 961-965.

Honda T, Nishibuchi M, Miwatani T, Kaper JB: Demonstration of a plasmid-borne gene encoding a thermostable direct hemolysin in Vibrio cholerae non-O1 strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986, 52: 1218-1220.

Hondo S, Goto I, Minematsu I, Ikeda N, Asano N, Ishibashi M, Kinoshita Y, Nishibuchi N, Honda T, Miwatani T: Gastroenteritis due to Kanagawa negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Lancet. 1987, 1 (8528): 331-332. 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)92062-9.

Nishibuchi M, Kaper JB: Thermostable direct hemolysin gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a virulence gene acquired by a marine bacterium. Infect Immun. 1995, 63: 2093-2099.

Makino K, Oshima K, Kurokawa K, Yokoyama K, Uda T, Tagomori K, Iijima Y, Najima M, Nakano M, Yamashita A, Kubota Y, Kimura S, Yasunaga T, Honda T, Shinagawa H, Hattori M, Iida T: Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet. 2003, 361 (9359): 743-749. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12659-1.

Park KS, Ono T, Rokuda M, Jang MH, Okada K, Iida T, Honda T: Functional characterization of two type III secretion systems of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infect Immun. 2004, 72 (11): 6659-6665. 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6659-6665.2004.

Kodama T, Rokuda M, Park KS, Cantarelli VV, Matsuda S, Iida T, Honda T: Identification and characterization of VopT, a novel ADP-ribosyltransferase effector protein secreted via the Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion system 2. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9: 2598-609. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00980.x.

Ono T, Park KS, Ueta M, Iida T, Honda T: Identification of proteins secreted via Vibrio parahaemolyticus type III secretion system 1. Infect Immun. 2006, 74 (2): 1032-1042. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1032-1042.2006.

Bhattacharjee RN, Park KS, Kumagai Y, Okada K, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Kumar H, Kawai T, Iida T, Honda T, Takeuchi O, Akira S: VP1686, a Vibrio type III secretion protein, induces toll-like receptor-independent apoptosis in macrophage through NF-kappaB inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281 (48): 36897-36904. 10.1074/jbc.M605493200.

Henke JM, Bassler BL: Quorum sensing regulates type III secretion in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186 (12): 3794-3805. 10.1128/JB.186.12.3794-3805.2004.

Hurley CC, Quirke A, Reen FJ, Boyd EF: Four genomic islands that mark post-1995 pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 104-10.1186/1471-2164-7-104.

Iguchi T, Kondo S, Hisatsune K: Vibrio parahaemolyticus O serotypes from O1 to O13 all produce R-type lipopolysaccharide: SDS-PAGE and compositional sugar analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995, 130 (2-3): 287-292. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07733.x.

Abbott SL, Powers C, Kaysner CA, Takeda Y, Ishibashi M, Joseph SW, Janda JM: Emergence of a restricted bioserovar of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as the predominant cause of Vibrio-associated gastroenteritis on the West Coast of the United States and Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 1989, 27 (12): 2891-2893.

DePaola A, Kaysner CA, Bowers J, Cook DW: Environmental investigations of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oysters after outbreaks in Washington, Texas, and New York (1997 and 1998). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000, 66 (11): 4649-4654. 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4649-4654.2000.

Okuda J, Ishibashi M, Abbott SL, Janda JM, Nishibuchi M: Analysis of the thermostable direct hemolysin (tdh) gene and the tdh-related hemolysin (trh) genes in urease-positive strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated on the West Coast of the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35 (8): 1965-1971.

Kaufman GE, Myers ML, Pass CL, Bej AK, Kaysner CA: Molecular analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from human patients and shellfish during US Pacific north-west outbreaks. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2002, 34 (3): 155-161. 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01076.x.

Kaysner CA, Abeyta C, Trost PA, Wetherington JH, Jinneman KC, Hill WE, Wekell MM: Urea hydrolysis can predict the potential pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated in the Pacific Northwest. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994, 60 (8): 3020-3022.

Okuda J, Ishibashi M, Hayakawa E, Nishino T, Takeda Y, Mukhopadhyay AK, Garg S, Bhattacharya SK, Nair GB, Nishibuchi M: Emergence of a unique O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Calcutta, India, and isolation of strains from the same clonal group from Southeast Asian travelers arriving in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35 (12): 3150-3155.

Ansaruzzaman M, Lucas M, Deen JL, Bhuiyan NA, Wang XY, Safa A, Sultana M, Chowdhury A, Nair GB, Sack DA, von Seidlein L, Puri MK, Ali M, Chaignat CL, Clemens JD, Barreto A: Pandemic serovars (O3:K6 and O4:K68) of Vibrio parahaemolyticus associated with diarrhea in Mozambique: spread of the pandemic into the African continent. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43 (6): 2559-2562. 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2559-2562.2005.

Gonzalez-Escalona N, Cachicas V, Acevedo C, Rioseco ML, Vergara JA, Cabello F, Romero J, RT E: Vibrio parahaemolyticus diarrhea, Chile, 1998 and 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005, 11 (1): 129-131.

Cabrera-Garcia ME, Vazquez-Salinas C, Quinones-Ramirez EI: Serologic and molecular characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from seawater and fish products of the Gulf of Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70 (11): 6401-6406. 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6401-6406.2004.

Chowdhury NR, Chakraborty S, Ramamurthy T, Nishibuchi M, Yamasaki S, Takeda Y, Nair GB: Molecular evidence of clonal Vibrio parahaemolyticus pandemic strains. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000, 6 (6): 631-636.

Martinez-Urtaza J, Lozano-Leon A, DePaola A, Ishibashi M, Shimada K, Nishibuchi M, Liebana E: Characterization of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus Isolates from clinical sources in Spain and comparison with Asian and North American pandemic isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (10): 4672-4678. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4672-4678.2004.

Matsumoto C, Okuda J, Ishibashi M, Iwanaga M, Garg P, Rammamurthy T, Wong HC, Depaola A, Kim YB, Albert MJ, Nishibuchi M: Pandemic spread of an O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and emergence of related strains evidenced by arbitrarily primed PCR and toxRS sequence analyses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38 (2): 578-585.

Yeung PS, Boor KJ: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of foodborne Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2004, 1 (2): 74-88. 10.1089/153531404323143594.

Pollack CV, Fuller J: Update on emerging infections from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection associated with eating raw oysters and clams harvested from Long Island Sound--Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, 1998. Ann Emerg Med. 1999, 34 (5): 679-680. 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70174-5.

Chowdhury NR, Stine OC, Morris JG, Nair GB: Assessment of evolution of pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42 (3): 1280-1282. 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1280-1282.2004.

Okura M, Osawa R, Arakawa E, Terajima J, Watanabe H: Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Pandemic Group-Specific DNA Sequence by Genomic Subtraction. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43 (7): 3533-3536. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3533-3536.2005.

Wong HC, Liu SH, Wang TK, Lee CL, Chiou CS, Liu DP, Nishibuchi M, Lee BK: Characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 from Asia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000, 66 (9): 3981-3986. 10.1128/AEM.66.9.3981-3986.2000.

Fuenzalida L, Hernandez C, Toro J, Rioseco ML, Romero J, Espejo RT: Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish and clinical samples during two large epidemics of diarrhoea in southern Chile. Environ Microbiol. 2006, 8 (4): 675-683. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00946.x.

McLaughlin JB, DePaola A, Bopp CA, Martinek KA, Napolilli NP, Allison CG, Murray SL, Thompson EC, Bird MM, Middaugh JP: Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters.N Engl J Med. 2005, 353: 1463-1470. 10.1056/NEJMoa051594.

Reen FJ, Almagro-Moreno S, Ussery D, Boyd EF: The genomic code: inferring Vibrionaceae niche specialization. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006, 4 (9): 697-704. 10.1038/nrmicro1476.

Genome Atlas. [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/GenomeAtlas/suppl/zoomatlas/]

Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ: Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104 (39): 15508-15513. 10.1073/pnas.0706532104.

Chen Y, Johnson JA, Pusch GD, Morris JG, Stine OC: The genome of non-O1 Vibrio cholerae NRT36S demonstrates the presence of pathogenic mechanisms that are distinct from O1 Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 2007, 75: 2645-7. 10.1128/IAI.01317-06.

Dziejman M, Serruto D, Tam VC, Sturtevant D, Diraphat P, Faruque SM, Rahman MH, Heidelberg JF, Decker J, Li L, Montgomery KT, Grills G, Kucherlapati R, Mekalanos JJ: Genomic characterization of non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae reveals genes for a type III secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102 (9): 3465-3470. 10.1073/pnas.0409918102.

Meador CE, Parsons MM, Bopp CA, Gerner-Smidt P, Painter JA, Vora GJ: Virulence gene- and pandemic group-specific marker profiling of clinical Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45 (4): 1133-1139. 10.1128/JCM.00042-07.

Maiden MCJ, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant DA, Feavers IM, Achtman M, Spratt BG: Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 3140–3145-10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140.

Maiden MC: Multilocus sequence typing of bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006, 60: 561-588. 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121325.

Bisharat N, Cohen DI, Maiden MC, Crook DW, Peto T, Harding RM: The evolution of genetic structure in the marine pathogen, Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Genet Evol. 2007, 7 (6): 685-693. 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.07.007.

Murphy RA, Boyd EF: Three pathogenicity islands of Vibrio cholerae can excise from the chromosome and form circular intermediates. J Bacteriol. 2008, 190: 636-647. 10.1128/JB.00562-07.

Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM: DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000, 406 (6795): 477-483. 10.1038/35020000.

Chen CY, Wu KM, Chang YC, Chang CH, Tsai HC, Liao TL, Liu YM, Chen HJ, Shen AB, Li JC, Su TL, Shao CP, Lee CT, Hor LI, Tsai SF: Comparative genome analysis of Vibrio vulnificus, a marine pathogen. Genome Res. 2003, 13 (12): 2577-2587. 10.1101/gr.1295503.

Ruby EG, Urbanowski M, Campbell J, Dunn A, Faini M, Gunsalus R, Lostroh P, Lupp C, McCann J, Millikan D, Schaefer A, Stabb E, Stevens A, Visick K, Whistler C, Greenberg EP: Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102 (8): 3004-3009. 10.1073/pnas.0409900102.

Jensen LJ, Friis C, Ussery DW: Three views of microbial genomes. Res Microbiol. 1999, 150 (9-10): 773-777. 10.1016/S0923-2508(99)00116-3.

Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M, Rajandream MA, Barrell BG, Parkhill J: ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21 (16): 3422-3423. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22 (22): 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Nei M, Gojobori T: Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986, 3: 418-426.

Nei M, Jin L: Variances of the average numbers of nucleotide substitutions within and between populations. Mol Biol Evol. 1989, 6: 290-300.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M: MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004, 5 (2): 150-163. 10.1093/bib/5.2.150.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank those who kindly provided us with the V. parahaemolyticus strains used in this study. Special thanks to G. Balakrish Nair for his advice and AQ3810 and to John Heidelberg for sequencing AQ3810. This study was supported in part by the University of Delaware Research Foundation (UDRF2007-2008), the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE and Science Foundation Ireland graduate fellowships to ALC and LMN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

ALC and LMN performed bacteriological, genetic and phylogenetic studies, helped with the experimental design and drafted the manuscript, OCS was involved in the genome sequencing, annotation and drafted the manuscript, TTB and DWU performed genome BLAST atlas analysis. MAP was involved in the experimental design and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12866_2008_543_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Genome BLAST Atlas of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus 27 genomes of members of the family Vibrionaceae for chromosome 1. V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810, V. cholerae 1587, AM-19226, MAK757, MO10, MZO-2, MZO-3, B33, NCTC8457, RC385, O395, V51, V52, 623-39, and 2740-80, V. harveyi ATCCBAA116, V. alginolyticus 12G01, Vibrio sp. Ex25, V. vulnificus CMCP6 and YJ016, V. splendidus 12B01, Vibrio sp. MED222, V. fischeri ES114, V. salmonicida LF1238, V. angustum S14, P. profundum SS9 and 3TCK for chromosome 1. The gaps or holes in the outer four circles represent regions present in V. parahaemolyticus strain RIMD2210633 that are absent from the other species. The innermost circles show DNA structure features, DNA stacking energy, DNA position preference, positive and negative coding strands are indicated by dark blue and red circle. Global direct and global inverted repeats are represented and the two inner most circles represent GC shew and AT content, respectively. (PDF 2 MB)

12866_2008_543_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. Genome BLAST Atlas of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus 27 genomes of members of the family Vibrionaceae for chromosome 2. V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 as reference strain (inner most circle) versus V. parahaemolyticus AQ3810, V. cholerae 1587, AM-19226, MAK757, MO10, MZO-2, MZO-3, B33, NCTC8457, RC385, O395, V51, V52, 623-39, and 2740-80, V. harveyi ATCCBAA116, V. alginolyticus 12G01, Vibrio sp. Ex25, V. vulnificus CMCP6 and YJ016, V. splendidus 12B01, Vibrio sp. MED222, V. fischeri ES114, V. salmonicida LF1238, V. angustum S14, P. profundum SS9 and 3TCK for chromosome 2. The gaps or holes in the outer four circles represent regions present in V. parahaemolyticus strain RIMD2210633 that are absent from the other species. The innermost circles show DNA structure features, DNA stacking energy, DNA position preference, positive and negative coding strands are indicated by dark blue and red circle. Global direct and global inverted repeats are represented and the two inner most circles represent GC shew and AT content, respectively. (PDF 2 MB)

12866_2008_543_MOESM3_ESM.ppt

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Linear comparison of V. parahaemolyticus RIMD2210633 and AQ3810 created using ACT (Artemis Comparison Tool) at the insertion sites of (A) VPaI-1 and VPaI-4, and (B) VPaI-5 and VPaI-6. A homologous block of genomic sequence (BLASTN matches) is indicated by red lines between the chromosomal regions examined. The location of the genomic islands (GIs) identified in RIMD2210633 are illustrated above, and in AQ3810 below the genome comparison. Horizontal arrows represent annotated genes, striped arrows represent integrases, and the direction of the arrow indicates gene orientation. (PPT 164 KB)

12866_2008_543_MOESM4_ESM.ppt

Additional file 4: Fig. S4. Linear comparison of V. parahaemolyticus strain RIMD2210633 and strain AQ3810 created using ACT [59] at the insertion sites of (A) VPaI-2 and VPaI-3, and (B) VPaI-9 and VPaI-10. A homologous block of genomic sequence (BLASTN matches) is indicated by red and blue lines between the chromosomes; blue lines indicate chromosomal inversion events. The location of Vibrio parahaemolyticus islands (VPaIs) identified is illustrated above for RIMD2210633 and below for AQ3810 the region examined. Horizontal arrows represent annotated genes, striped arrows represent integrases, and the direction of the arrow indicates gene orientation. (PPT 143 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Boyd, E.F., Cohen, A.L.V., Naughton, L.M. et al. Molecular analysis of the emergence of pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. BMC Microbiol 8, 110 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-8-110

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-8-110