Abstract

Background

Alginate overproduction in P. aeruginosa, also referred to as mucoidy, is a poor prognostic marker for patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). We previously reported the construction of a unique mucoid strain which overexpresses a small envelope protein MucE leading to activation of the protease AlgW. AlgW then degrades the anti-sigma factor MucA thus releasing the alternative sigma factor AlgU/T (σ22) to initiate transcription of the alginate biosynthetic operon.

Results

In the current study, we mapped the mucE transcriptional start site, and determined that P mucE activity was dependent on AlgU. Additionally, the presence of triclosan and sodium dodecyl sulfate was shown to cause an increase in P mucE activity. It was observed that mucE-mediated mucoidy in CF isolates was dependent on both the size of MucA and the genotype of algU. We also performed shotgun proteomic analysis with cell lysates from the strains PAO1, VE2 (PAO1 with constitutive expression of mucE) and VE2ΔalgU (VE2 with in-frame deletion of algU). As a result, we identified nine algU-dependent and two algU-independent proteins that were affected by overexpression of MucE.

Conclusions

Our data indicates there is a positive feedback regulation between MucE and AlgU. Furthermore, it seems likely that MucE may be part of the signal transduction system that senses certain types of cell wall stress to P. aeruginosa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

P. aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium, is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) [1]. In CF, P. aeruginosa is often isolated from sputum samples and exhibits a phenotype called mucoidy, which is due to overproduction of an exopolysaccharide called alginate. It is also an environmental bacterium which normally does not overproduce alginate [2]. The emergence of mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates in CF sputum specimens signifies the onset of chronic respiratory infections. Mucoidy plays an important role in the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa infections in CF, which includes, but is not limited to: increased resistance to antibiotics [1], increased resistance to phagocytic killing [3, 4] and assistance in evading the host’s immune response [3].

A major pathway for the conversion to mucoidy in P. aeruginosa is dependent upon AlgU (AlgT, σ22), an alternative sigma factor that drives transcription of algD encoding the key enzyme for alginate biosynthesis [5, 6]. Previous studies have shown that several genes take part in the regulation of AlgU activation and alginate overproduction. MucA is a trans-membrane protein that negatively regulates mucoidy by acting as an anti-sigma factor via sequestering AlgU to the cytoplasmic membrane [7]; MucB and intra-membrane proteases AlgW, MucP and ClpXP were reported to affect alginate production by affecting the stability of MucA [8]. A small envelope protein called MucE was found to be a positive regulator for mucoid conversion in P. aeruginosa strains with a wild type MucA [9]. The mechanism for mucE induced mucoidy is due to its C-terminal –WVF signal, which can activate the protease AlgW possibly by interaction with the PDZ domain [9]. Upon activation, AlgW initiates the proteolytic degradation of the periplasmic portion of MucA, causing the release of AlgU to drive expression of the alginate biosynthetic operon [9]. While the function of MucE as an alginate inducer was identified, its physiological role, and its role in the regulation of mucoidy in clinical isolates, remains unknown.

Comparative analysis through Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) using the genomes of Pseudomonas species from the public databases reveals that MucE orthologues are found only in the strains of P. aeruginosa[9]. In order to study the role and regulation of MucE in P. aeruginosa, we first mapped the mucE transcriptional start site. We then examined the effect of five different sigma factors on the expression of mucE in vivo. Different cell wall stress agents were tested for the induction of mucE transcription. Expression of MucE was also analyzed in non-mucoid CF isolates to determine its ability to induce alginate overproduction.

Methods

Bacteria strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB, Tryptone 10 g/L, Yeast extract 5 g/L and sodium chloride 5 g/L) or LB agar. P. aeruginosa strains were grown at 37°C in LB or on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA) plates (Difco). When required, carbenicillin, tetracycline or gentamicin were added to the growth media. The concentration of carbenicillin, tetracycline or gentamycin was added at the following concentrations: for LB broth or plates 100 μg ml-1, 20 μg ml-1 or 15 μg ml-1, respectively. The concentration of carbenicillin, tetracycline or gentamycin to the PIA plates was 300 μg ml-1, 200 μg ml-1 or 200 μg ml-1, respectively.

The mucEprimer extension assay

Total RNA was isolated from P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown to an OD600 of 0.6 in 100 ml LB at 37°C as previously described [10]. The total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers for mucE (PA4033), seq 1 (5′-CCA TGG CTA CGA CTC CTT GAT AG-3′) and seq 2 (5′-CAA GGG CTG GTC GCG ACC AG-3′), were radio-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and γP32-ATP. Primer extensions were performed using the Thermoscript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with either PA4033 seq 1 or seq 2 with 10–20 μg of total RNA. Extensions were performed at 55°C for an hour. Primer extension products then were electrophoresed through a 6% acrylamide/8M urea gel along with sequencing reactions (Sequenase 2.0 kit, USB, Cleveland, OH) using the same primers used in the extension reactions.

Transformation and conjugation

E. coli One Shot TOP10 cells (Invitrogen) were transformed via standard heat shock method according to the supplier’s instructions. Plasmid transfer from E. coli to Pseudomonas was performed via triparental conjugations using the helper plasmid pRK2013 [11].

Generating PAO1 miniCTX-P mucE -lacZreporter strain

PAO1 genomic DNA was used as a template to amply 618 bp upstream of the start site (ATG) of mucE using two primers with built-in restriction sites, HindIII-mucE-P-F (5′-AAA GCT TGG TCG TTG AAA GTC TGC ACC TCA-3′) and EcoRI-mucE-P-R: (5′-CGA ATT CGG TTG ATG TCA CGC AAA CGT TGG C-3′). The P mucE amplicon was TOPO cloned and digested with HindIII and EcoRI restriction enzymes before ligating into the promoterless Pseudomonas integration vector miniCTX-lacZ. The promoter fusion construct miniCTX-P mucE -lacZ was integrated onto the P. aeruginosa chromosome of strain PAO1 at the CTX phage att site [12] following triparental conjugation with E. coli containing the pRK2013 helper plasmid [11].

Screening for a panel of chemical agents that can promote P mucE transcription

Membrane disrupters and antibiotics were first tested by serial dilution to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for strain PAO1::attB::P mucE -lacZ. An arbitrary sub-MIC concentration for each compound was then tested for the induction effect through the color change of 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal, diluted in dimethylformamide to a concentration of 4% (w/v)). The final concentration of the compounds used in this study are listed as follows: triclosan 25 μg/ml, tween-20 0.20% (v/v), hydrogen peroxide 0.15%, sodium hypochlorite 0.03%, SDS 0.10%, ceftazidimine 2.5 μg/ml, tobramycin 2.5 μg/ml, gentamicin 2.5 μg/ml, colisitin 2.5 μg/ml, and amikacin 2.5 μg/ml. PAO1::attB::P mucE -lacZ was cultured overnight in 2 ml LB broth, 10 μl of overnight culture and 10 μl of 4% X-gal was added to each treatment culture tube (2 ml LB broth + cell wall stress agent). The cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm and were used to visually observe the change of the color. LB broth lacking X-gal was used as a negative control.

The β-galactosidase activity assay

Pseudomonas strains were cultured at 37°C on three PIA plates. After 24 hours, bacterial cells were harvested and re-suspended in PBS. The OD600 was measured and adjusted to approximately 0.3. Cells were then permeabilized using toluene, and β-galactosidase activity was measured at OD420 and OD550. The results in Miller Units were calculated according to this formula: Miller Units = 1000 × [OD420 - (1.75 × OD550)]/[Reaction time (minutes) × Volume (ml) × OD600] [13]. The reported values represent an average of three independent experiments with standard error.

Alginate assay

P. aeruginosa strains were grown at 37°C on PIA plates in triplicate for 24 hrs or 48 hrs. The bacteria were collected and re-suspended in PBS. The OD600 was analyzed for the amount of uronic acid in comparison with a standard curve made with D-mannuronic acid lactone (Sigma-Aldrich), as previously described [14].

iTRAQ®MALDI TOF/TOF proteome analysis

Strains PAO1, VE2 and VE2ΔalgU were cultured on PIA plates for 24 hrs at 37°C. Protein preparation and iTRAQ mass spectrometry analysis was performed according to previously described methods [15].

Results

Mapping of the mucEpromoter in PAO1

We previously identified MucE, a small envelope protein, which induces mucoid conversion in P. aeruginosa when overexpressed [9]. Induction of MucE activates the intramembrane protease AlgW resulting in activation of the cytoplasmic sigma factor AlgU and conversion from nonmucoidy to mucoidy in strains with a wild type MucA [9]. Stable production of copious amounts of alginate is characteristic of strain VE2 which carries a mariner transposon insertion before mucE[9]. This insertion is likely responsible for the constitutive expression of the mucE gene [9]. However, it is unclear how mucE is naturally expressed in parent PAO1. To determine this, primer extension analysis of the mucE promoter region was performed. With higher amounts of PAO1 RNA (20 μg), we observed one prominent transcriptional start site that is initiated 88 nucleotides upstream of the mucE translational start site (Figure 1). This suggests that, under these conditions, mucE has one promoter that is active in PAO1.

Mapping of the mucE transcriptional start site in P. aeruginosa PAO1. A) Primer extension mapping of mRNA 5′ end. Total RNA was isolated from the non-mucoid PAO1. The conditions used for labelling of primers for mucE are described in Methods. The primer extension product was run adjacent to the sequencing ladder generated with the same primer as highlighted in the mucE sequence. The arrow indicates the position of the P1 transcriptional start site of mucE. B) The mucE promoter sequence in strains PAO1 and PAO1VE2. The transposon (Tn) insertion site of PAO1VE2 is underlined along with the putative ribosome binding site (RBS) for mucE. In strain PAO1VE2, the gentamicin resistance cassette (aacC1) gene carries a σ70 dependent promoter. The arrow pointing leftward corresponds to the position of primer seq 1 used for mapping the P1 start site.

The alternative sigma factor AlgU activates transcription of mucE in vivo

In order to determine which sigma factor is responsible for driving mucE transcription, miniCTX-P mucE -lacZ was integrated onto the PAO1 chromosome. To identify the sigma factor that activates the expression of P mucE , we expressed P. aeruginosa sigma factors (RpoD, RpoN, RpoS, RpoF and AlgU) in trans and measured P mucE -lacZ activity in this PAO1 fusion strain. As seen in Figure 2, Miller assay results showed that AlgU significantly increased the promoter activity of P mucE in PAO1. However, we did not observe any significant increases in promoter activity of P mucE with other sigma factors tested in this study. As stated earlier, AlgU is a sigma factor that controls the promoter of the alginate biosynthetic gene algD[5, 6]. In order to determine whether the activity of P mucE is elevated in mucoid strains, pLP170-P mucE was conjugated into mucoid laboratory and clinical P. aeruginosa strains. As seen in Figures 3A and 3B, the activity of P mucE increased in mucoid laboratory and CF isolates.

Effect of overexpression of sigma factors on the P mucE expression. The sigma factors AlgU, RpoD, RpoN, RpoS and RpoF were expressed from an arabinose-inducible promoter in pHERD20T [16], and the P mucE activity was determined via β-galactosidase assay from a merodiploid strain of PAO1 carrying PmucE-lacZ integrated on the chromosome. The values reported in this figure represent an average of three independent experiments with standard error.

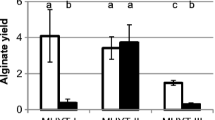

Correlation between the P mucE activity and alginate overproduction in various strains of P. aeruginosa . A) Measurement of the P mucE activity in various mucoid laboratory and clinical strains. B) Measurement of alginate production (μg/ml/OD600) by the same set of strains as in A grown on PlA plates without carbenicillin for 24 h at 37°C. The algU(WT)-PAO1 represents the PAO1 strain contained the pHERD20T-algU(WT). The values reported in this figure represent an average of three independent experiments with standard error.

Cell wall stress promotes expression of mucE from P mucE

Since the mucE promoter was active in nonmucoid PAO1 and further increased in mucoid cells (Figure 3A), the conditions that induce mucE expression were examined. To do this, we used the same P mucE -lacZ strain of PAO1 to measure the activation of mucE by some compounds previously shown to cause cell wall perturbations [17, 18]. The phenotypes of strains harboring the P mucE -lacZ fusion in the presence of various cell wall stress agents are shown in Figure 4A. While sodium hypochlorite and colistin didn’t induce a visual change in P mucE activity, three compounds, triclosan, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and ceftazidime induced marked expression of P mucE -lacZ in PAO1. Each resulted in elevated levels of β-galactosidase activity as indicated by the blue color of the growth media. This suggests that the P mucE promoter activity was increased in response to these stimuli (Figure 4A). Miller assays were performed to measure the changes in P mucE -lacZ activity due to these compounds. Triclosan increased P mucE -lacZ activity by almost 3-fold over LB alone (Figure 4B). An increase in P mucE -lacZ should increase P algU -lacZ activity. As expected, triclosan caused a 5-fold increase in P algU -lacZ activity. However, SDS and ceftazidime increased the P mucE -lacZ activity, but did not promote the P algU -lacZ activity (Figure 4B).

Induction of P mucE activity by cell wall stress. A. A 1/200 dilution of the PAO1::attB::P mucE -lacZ recombinant strain grown overnight was inoculated into LB media containing X-gal and the agents listed as follows, 1) LB (control), 2) triclosan 25 μg/ml, 3) tween-20 0.20% (v/v), 4) hydrogen peroxide 0.15%, 5) bleach 0.03%, 6) SDS 0.10%, 7) ceftazidimine 2.5 μg/ml, 8) tobramycin 2.5 μg/ml, 9) gentamicin 2.5 μg/ml, 10) colisitin 2.5 μg/ml, and 11) amikacin 2.5 μg/ml. B. Triclosan, SDS, and ceftazidimine were tested for the induction of the P mucE and P algU promoters. The activities of the promoter fusions were measured by β-galactosidase activity as described in Methods.

Alginate production is reduced in the mucEmutant compared to PAO1

Expression of mucE can cause alginate overproduction [9]. However, we wondered if mucE would affect transcriptional activity at P algU and P algD promoters. In order to determine this, both pLP170-P algU and pLP170-P algD with each promoter fused to a promoterless lacZ gene were conjugated into PAO1 and PAO1VE2, respectively. As seen in Additional file 1: Figure S1, the activity of P algU (PAO1VE2 vs. PAO1: 183,612.04 ± 715.23 vs. 56.34 ± 9.68 Miller units) and P algD (PAO1VE2 vs PAO1: 760,637.8 ± 16.87 vs. 138.18 ± 9.68 Miller units) was significantly increased in the mucE over-expressed strain PAO1VE2. Although, Qiu et al. [9] have reported that AlgU is required for MucE induced mucoidy, we wanted to know whether MucE is required for AlgU induced mucoidy. As seen in Additional file 1: Figure S2, we did not observe that the over-expression of MucE induced mucoidy in PAO1ΔalgU. This result is consistent with what was previously reported by Qiu et al.[9]. However, the alginate production induced by AlgU was decreased in the mucE knockout strain. The alginate production induced by AlgU in two isogenic strains, PAO1 and PAO1mucE::ISphoA/hah is 224.00 ± 7.35 and 132.81 ± 2.66 μg/ml/OD600, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S2). These results indicate that alginate overproduction in PAO1 does not require MucE. However, MucE can promote the activity of AlgU resulting in a higher level of alginate production in PAO1 compared to the mucE knockout. Previously, Boucher et al.[19] and Suh et al.[20] have reported that sigma factors RpoN and RpoS were involved in alginate regulation. In order to determine whether mucE induced mucoidy was also dependent on other sigma factors besides AlgU, pHERD20T-mucE was conjugated and over-expressed in PAO1ΔrpoN, PAO1rpoS::ISlacZ/hah and PAO1rpoF::ISphoA/hah. The results showed that the mucE induction caused mucoid conversion in PAO1rpoS::ISlacZ/hah and PAO1rpoF::ISphoA/hah when 0.1% L-arabinose was added to the media. However, 0.5% L-arabinose was required for mucoid conversion in PAO1ΔrpoN. The alginate production induced by MucE in PAO1rpoS::ISlacZ/hah, PAO1rpoF::ISphoA/hah and PAO1ΔrpoN is 150.62 ± 5.27, 85.53 ± 4.10 and 31.84 ± 0.25 μg/ml/OD600, respectively. These results suggested that RpoN, RpoS and RpoF are not required for MucE-induced mucoidy in PAO1. Conversely, over-expression of these sigma factors rpoD, rpoN, rpoS and rpoF did not induce mucoid conversion in PAO1. When the strains of PAO1 with sigma factor overexpression were measured for alginate production, the level is as follows: 5.11 ± 1.25 (+rpoD), 13.07 ± 4.16 (+rpoN), 3.50 ± 0.10 (+rpoS) and 7.68 ± 1.23 (+rpoF) μg/ml/OD600.

MucE-induced mucoidy in clinical CF isolates is based on two factors, size of MucA and genotype of algU

Although, Qiu et al. [9] have reported that over-expression of mucE can induce mucoidy in laboratory strains PAO1 and PA14, its ability to induce mucoidy in clinical CF isolates has not been investigated. Particularly, mucE’s relationship to mucA mutations is unknown since different mutations would result in production of MucA with various molecular masses. To test if the length of MucA had an effect on MucE-mediated mucoid induction, we selected a group of nonmucoid clinical isolates and observed any phenotypic change after overexpression of mucE. Figure 5 summarizes the results. First, strains with wild type AlgU and MucA became mucoid. Although, MucA of CF2 carries a missense mutation, CF2 became mucoid. Secondly, as seen in Figure 5 and Additional file 1: Table S2, mucE could induce mucoidy in CF17 (MucA143 + 3 aa) and CF4349 (MucA125 + 3 aa) with wild type AlgU, but not in strains containing algU carrying a missense mutation [CF14 (MucA143 + 3 aa), FRD2 (MucA143 + 3 aa) and CF149 (MucA125 + 3 aa)]. Thirdly, overexpression of mucE did not induce mucoidy in CF11 and CF28, whose MucA length was 117aa, despite a wild type AlgU in CF11. These results suggest that MucE-mediated mucoidy is dependent on the combination of two factors, MucA length and algU genotype (Figure 5). The effect of MucE on mucoid induction is more obvious in strains with MucA length up to 125 amino acid residues coupled with wild type AlgU, but missense mutations in AlgU can significantly reduce the potency of MucE.

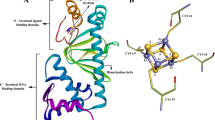

MucE-mediated mucoid conversion in nonmucoid clinical isolates is dependent on MucA length and algU genotype. The length of MucA is shown with two functional domains as depicted with RseA_N and RseA_C, which represent the N-terminal domain of MucA predicted to interact with AlgU in the cytoplasm and C-terminal domain of MucA located in the periplasm, respectively. The domain prediction is based on the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD). The blue vertical line represents the truncated MucA due to the mutation from each CF strain relative to the full length of wild type MucA. The type of AlgU is indicated for each CF strain (WT or mutant with the indicated change of amino acid due to missense mutation). Those strains that become mucoid upon mucE induction are shown in red, while those that remain nonmucoid are shown in black. The red arrow indicates the cutting site of MucA by AlgW. pHERD20T-mucE was conjugated into these non-mucoid CF isolates, and then incubated on PIA plates containing carbenicillin and 0.1% L-arabinose at 37°C for 24 hours. Mucoid or non-mucoid phenotype was scored based on visual inspection and the amount of alginate production. The quantity of alginate was measured and shown in Table S2.

Mutant AlgUs display partial activity resulting in decreased amount of alginate

Schurr et al. have reported that second-site suppressor mutations in algU can affect mucoidy [21]. DeVries and Ohman [22] also reported that mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing P. aeruginosa is often due to spontaneous mutations in algT (algU). Recently, Damkiaer et al. [23] showed that point mutations can result in a partially active AlgU. To test whether the activity of AlgU from different CF isolates is affected due to mutation, the CF149 and CF28 algU genes were cloned and over-expressed in PAO1ΔalgU and PAO1miniCTX-P algD -lacZ, respectively. As seen in Figure 6, these constructs retained the ability to promote the transcription of P algD and alginate production. Also, when transposon libraries were screened for mucoid revertants in CF149 [24] and FRD2, three and five mucoid mutants in CF149 and FRD2, respectively, were identified due to transposon insertion before algU causing the overexpression of algU (data not shown). However, the activity of the mutant AlgU is lower than that of wild type AlgU (Figure 6). In order to determine whether the mutant AlgU still has the ability to promote mucE transcription, algU genes from CF149 and CF28 were cloned into pHERD20T, respectively, and over-expressed in PAO1 miniCTX-P mucE -lacZ strain. As seen in Figure 2, mutant forms of AlgU were still able to promote mucE transcription, albeit at a reduced level.

AlgU with missense mutations induces decreased amount of alginate compared to wild type AlgU. PAO1, CF149 and CF28 algUs were cloned into pHERD20T vector, and conjugated into PAO1ΔalgU and PAO1miniCTX-P algD -lacZ, respectively. Alginate production (μg/ml/OD600) and P algD activity were measured after culture overnight on PIA plates supplemented with 300 μg/ml of carbenicillin. The values reported here represent an average of three independent experiments with standard error.

Characterization of the MucE regulon using iTRAQ analysis

In order to determine the effect of mucE expression on the proteome change, we performed iTRAQ proteome analysis via MALDI TOF/TOF. Total protein lysates of PAO1, VE2 (PAO1 with constitutive expression of mucE) and VE2ΔalgU (VE2 with in-frame deletion of algU) were collected and analyzed. Within the three samples, 166 unique proteins were identified with 1455 peptides assayed at/or above 95% confidence. The data set was then filtered to include only proteins that were significantly different between samples and the number of the detected peptides for each protein more than three (Additional file 1: Table S3). By comparing the proteomes of VE2 to PAO1, the effects of increased MucE levels on PAO1 were examined; while comparing VE2ΔalgU to PAO1 allowed for the determination of AlgU-independent protein production in VE2. As seen in Additional file 1: Table S3, compared to PAO1, 11 proteins were differentially expressed due to mucE over-expression, and two of them (elongation factor Tu and transcriptional regulator MvaT) are AlgU-independent.

Discussion

MucE is a small envelope protein whose overexpression can promote alginate overproduction in P. aeruginosa strains with a wild type MucA [9]. Here, we observed that AlgU can induce the expression from P mucE , and consistent with this result, the P mucE activity is higher in mucoid strains than in non-mucoid strains (Figure 3). AlgU is a stress-related alternate sigma factor that is auto-regulated from its multiple promoters [25]. As a sigma factor, AlgU drives transcription of the alginate biosynthetic gene algD[5] and the alginate regulator gene algR[26]. As shown in this study, AlgU can also activate the transcription of mucE, and subsequently, depending on the level of induction, MucE can increase P algU and P algD activity resulting in mucoid conversion in clinical strains. Together, these results suggest a positive feedback mechanism of action in which AlgU activates mucE expression at the P mucE promoter, and in return, the increased level of MucE can increase AlgU activity by activating AlgW, which further degrades MucA (Figure 7). This regulation between MucE and AlgU probably ensures that a cell, upon exposure to stress, can rapidly reach the desired level of AlgU and alginate production. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that a higher level of alginate production requires mucE in P. aeruginosa strains with a wild type MucA (Additional file 1: Figure S2). We also noted that some cell wall stress agents, like triclosan and SDS can induce the expression of mucE. However, the differential activation at P algU by triclosan but not SDS suggests SDS may not be an inducer at P algU , and/or the stimulation by SDS was not high enough to initiate the positive feedback regulation of MucE by AlgU. Nevertheless, this observation is consistent with what was previously reported by Wood et al. regarding the absence of induction at P algD by SDS [27]. Furthermore, we found that strain PAO1 does not become mucoid when cultured on LB or PIA plates supplemented with triclosan or SDS at the concentration as used in Figure 4 (data not shown).

Schematic diagram summarizing the positive feedback between MucE and AlgU and their relationship to alginate overproduction. AlgU is an alternative sigma factor that controls the alginate biosynthetic operon. Additionally, AlgU regulates itself, as well as drives transcription of mucE. MucE has the C-terminal –WVF motif that can activate the protease AlgW, thereby causing the degradation of the anti-sigma factor MucA. The degradation of MucA results in the release of AlgU to activate transcription at the PalgU, P algD and P mucE promoter sites.

Qiu et al. have reported that MucE can induce alginate overproduction when over-expressed in vivo[9]. However, nothing was known about the regulation of mucE. Recently, the genome-wide transcriptional start sites of many genes were mapped by RNA-seq in P. aeruginosa strain PA14 [28]. However, the transcriptional start site of the mucE gene (PA14_11670) was not included. In this study, we reported the mapping of the mucE transcriptional start site. Furthermore, we found the transcription of mucE is dependent on AlgU. Analysis of the upstream region of mucE reveals an AlgU promoter-like sequence (Figure 1). Previously, Firoved et al. identified 35 genes in the AlgU regulon, based on scanning for AlgU promoter consensus sequence (GAACTTN16-17TCtgA) in the PAO1 genome [26]. In this study, we found that AlgU can activate the transcription of mucE. In order to determine whether AlgU can bind to P mucE region, AlgU was purified (Additional file 1: Figure S3) and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed. As seen in Additional file 1: Figure S4, our results showed that AlgU affected the mobility of P mucE DNA, especially in the presence of E. coli RNA polymerase core enzyme, suggesting a direct binding of AlgU to P mucE . However, whether small regulatory RNAs or other unknown regulator proteins are also involved in the transcriptional regulation of mucE needs further study. LptF is another example of an AlgU-dependent gene, but doesn’t have the consensus sequence in the promoter region [29]. While MucE, as a small envelope protein is positively regulated through a feedback mechanism, it’s not clear how many AlgU-regulated genes follow the same pattern of regulation as MucE.

The mucA mutation is a major mechanism for the conversion to mucoidy. Mutation can occur throughout the mucA gene (585 bps) [30]. These mutations result in the generation of MucA proteins of different sizes. For example, unlike the wild type MucA with 194 amino acid residues, MucA25, which is produced due to a frameshift mutation, results in a protein containing the N-terminal 59 amino acids of MucA, fused with a stretch of 35 amino acids without homology to any known protein sequence [31]. MucA25 lacks the trans-membrane domain of wild type MucA, predicting a cytoplasmic localization. Therefore, different mucA mutations could possibly result in different cellular compartment localization. Identification of MucE’s function as an inducer of alginate in strains with wild type MucA and AlgU strongly suggests MucE acts through interaction with AlgW in the periplasm. On the other hand, the loss of this predicted MucA-AlgW interaction can be seen in two strains, CF11 and CF28, which lack the major cleavage site of AlgW [32] (Figure 5). Interestingly, we observed that the missense mutation in algU can reduce, but not completely abolish, the activity of AlgU as an activator for alginate production. This data may explain why mutant algU alleles have reduced P mucE activity (Figure 2). Furthermore, since AlgU is an auto-regulated protein [25], this may explain why the P mucE activity induced by mutant AlgU is lower than that of wild type AlgU. A slightly higher activity of P mucE noted in CF149(+algU) than in PAO1VE1 (Figure 3A) could be due to a combined effect of dual mutation of algU and mucA in CF149. In strains of FRD2 and CF14, the retention of the AlgW cleavage site is not sufficient to restore mucoidy. This is because of the partial function of AlgU, which can be seen with alginate production and AlgU-dependent P algD promoter activity (Figure 6). Altogether, these results suggest that mucoidy in clinical isolates can be modulated by a combination of two factors, the size of the MucA protein and the genotype of the algU allele in a particular strain. MucA size determines its cellular localization and its ability to sequester AlgU, and the algU allele determines whether AlgU is fully or partially active.

The iTRAQ results showed that the expression of two proteins was significantly increased and the expression of nine proteins was decreased in the mucE over-expressed strain VE2 (Additional file 1: Table S3). Of these 11 proteins, nine of them are AlgU dependent, for including flagellin type B. Garrett et al. previously reported that AlgU can negatively regulate flagellin type B and repress flagella expression [33]. However, no AlgU consensus promoter sequences were found within the upstream of the 11 regulated genes through bioinformatics analysis, indicating that these may be indirect effect. In addition, two proteins (elongation factor Tu and transcriptional regulator MvaT) were significantly decreased when compared to PAO1 proteome, but remained unchanged when comparison was made between VE2 and VE2ΔalgU, suggesting the reduction of these two proteins was independent of AlgU in the MucE over-expressed strain. MvaT is a global regulator of virulence in P. aeruginosa[34], and elongation factor Tu is important for growth and translation. Elongation factor Tu has also been shown to act as a chaperone in E. coli, consistent with induction of proteins involved in responding to heat or other protein damaging stresses [35]. Recently, elongation factor Tu has been shown to have a unique post-translational modification that has roles in colonization of the respiratory tract [36, 37]. The differential expression of Tu due to mucE overexpression suggests there may be signaling networks dependent upon mucE that we have not yet been identified. Although, previous studies have shown that the growth rate is slower in mucoid strains and the virulence is increased after deleting AlgU [15, 38], the relationship between MucE and growth or virulence need further study. Together, iTRAQ analysis suggests that MucE signaling affected both AlgU-dependent and AlgU-independent protein expression.

Conclusions

The alternative sigma factor AlgU was responsible for mucE transcription. Together, our results suggest there is a positive feedback regulation of MucE by AlgU in P. aeruginosa, and the expression of mucE can be induced by exposure to certain cell wall stress agents, suggesting that mucE may be part of the signal transduction that senses the cell wall stress to P. aeruginosa.

References

Govan JR, Deretic V: Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996, 60 (3): 539-574.

May TB, Shinabarger D, Maharaj R, Kato J, Chu L, DeVault JD, Roychoudhury S, Zielinski NA, Berry A, Rothmel RK, et al: Alginate synthesis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a key pathogenic factor in chronic pulmonary infections of cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991, 4 (2): 191-206.

Leid JG, Willson CJ, Shirtliff ME, Hassett DJ, Parsek MR, Jeffers AK: The exopolysaccharide alginate protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria from IFN-gamma-mediated macrophage killing. J Immunol. 2005, 175 (11): 7512-7518.

Pier GB, Coleman F, Grout M, Franklin M, Ohman DE: Role of alginate O acetylation in resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2001, 69 (3): 1895-1901. 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1895-1901.2001.

Martin DW, Holloway BW, Deretic V: Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: AlgU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J Bacteriol. 1993, 175 (4): 1153-1164.

Hershberger CD, Ye RW, Parsek MR, Xie ZD, Chakrabarty AM: The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative sigma factor (sigma E). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995, 92 (17): 7941-7945. 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7941.

Xie ZD, Hershberger CD, Shankar S, Ye RW, Chakrabarty AM: Sigma factor-anti-sigma factor interaction in alginate synthesis: inhibition of AlgT by MucA. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178 (16): 4990-4996.

Damron FH, Goldberg JB: Proteolytic regulation of alginate overproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2012, 84 (4): 595-607. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08049.x.

Qiu D, Eisinger VM, Rowen DW, Yu HD: Regulated proteolysis controls mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104 (19): 8107-8112. 10.1073/pnas.0702660104.

Lizewski SE, Schurr JR, Jackson DW, Frisk A, Carterson AJ, Schurr MJ: Identification of AlgR-regulated genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by use of microarray analysis. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186 (17): 5672-5684. 10.1128/JB.186.17.5672-5684.2004.

Figurski DH, Helinski DR: Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979, 76 (4): 1648-1652. 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648.

Hoang TT, Kutchma AJ, Becher A, Schweizer HP: Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid. 2000, 43 (1): 59-72. 10.1006/plas.1999.1441.

Miller JH: Beta-Galactosidase Assay. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Edited by: Miller JH. 1972, Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 352-355.

Damron FH, Qiu D, Yu HD: The Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensor kinase KinB negatively controls alginate production through AlgW-dependent MucA proteolysis. J Bacteriol. 2009, 191 (7): 2285-2295. 10.1128/JB.01490-08.

Damron FH, Owings JP, Okkotsu Y, Varga JJ, Schurr JR, Goldberg JB, Schurr MJ, Yu HD: Analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulon controlled by the sensor kinase KinB and sigma factor RpoN. J Bacteriol. 2012, 194 (6): 1317-1330. 10.1128/JB.06105-11.

Qiu D, Damron FH, Mima T, Schweizer HP, Yu HD: PBAD-based shuttle vectors for functional analysis of toxic and highly regulated genes in Pseudomonas and Burkholderia spp. and other bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008, 74 (23): 7422-7742. 10.1128/AEM.01369-08.

Wood LF, Ohman DE: Use of cell wall stress to characterize sigma 22 (AlgT/U) activation by regulated proteolysis and its regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 72 (1): 183-201. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06635.x.

Damron FH, Davis MR, Withers TR, Ernst RK, Goldberg JB, Yu G, Yu HD: Vanadate and triclosan synergistically induce alginate production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 2011, 81 (2): 554-570. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07715.x.

Boucher JC, Schurr MJ, Deretic V: Dual regulation of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and sigma factor antagonism. Mol Microbiol. 2000, 36 (2): 341-351. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01846.x.

Suh SJ, Silo-Suh L, Woods DE, Hassett DJ, West SE, Ohman DE: Effect of rpoS mutation on the stress response and expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181 (13): 3890-3897.

Schurr MJ, Martin DW, Mudd MH, Deretic V: Gene cluster controlling conversion to alginate-overproducing phenotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: functional analysis in a heterologous host and role in the instability of mucoidy. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176 (11): 3375-3382.

DeVries CA, Ohman DE: Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternate sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176 (21): 6677-6687.

Damkiaer S, Yang L, Molin S, Jelsbak L: Evolutionary remodeling of global regulatory networks during long-term bacterial adaptation to human hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110 (19): 7766-7771. 10.1073/pnas.1221466110.

Yeshi Y, Ryan Withers T, Xin W, Yu HD: Evidence for sigma factor competition in the regulation of alginate production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8 (8): e72329-10.1371/journal.pone.0072329.

Martin DW, Schurr MJ, Yu H, Deretic V: Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to sigma E and stress response. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176 (21): 6688-6696.

Firoved AM, Boucher JC, Deretic V: Global genomic analysis of AlgU (sigma(E))-dependent promoters (sigmulon) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and implications for inflammatory processes in cystic fibrosis. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184 (4): 1057-1064. 10.1128/jb.184.4.1057-1064.2002.

Wood LF, Leech AJ, Ohman DE: Cell wall-inhibitory antibiotics activate the alginate biosynthesis operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Roles of sigma (AlgT) and the AlgW and Prc proteases. Mol Microbiol. 2006, 62 (2): 412-426. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05390.x.

Wurtzel O, Yoder-Himes DR, Han K, Dandekar AA, Edelheit S, Greenberg EP, Sorek R, Lory S: The single-nucleotide resolution transcriptome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in body temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8 (9): e1002945-10.1371/journal.ppat.1002945.

Damron FH, Napper J, Teter MA, Yu HD: Lipotoxin F of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an AlgU-dependent and alginate-independent outer membrane protein involved in resistance to oxidative stress and adhesion to A549 human lung epithelia. Microbiology. 2009, 155 (Pt 4): 1028-1038.

Boucher JC, Yu H, Mudd MH, Deretic V: Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect Immun. 1997, 65 (9): 3838-3846.

Qiu D, Eisinger VM, Head NE, Pier GB, Yu HD: ClpXP proteases positively regulate alginate overexpression and mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2008, 154 (Pt 7): 2119-2130.

Cezairliyan BO, Sauer RT: Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgW protease cleavage of MucA by peptide signals and MucB. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 72 (2): 368-379. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06654.x.

Garrett ES, Perlegas D, Wozniak DJ: Negative control of flagellum synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is modulated by the alternative sigma factor AlgT (AlgU). J Bacteriol. 1999, 181 (23): 7401-7404.

Diggle SP, Winzer K, Lazdunski A, Williams P, Camara M: Advancing the quorum in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: MvaT and the regulation of N-acylhomoserine lactone production and virulence gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184 (10): 2576-2586. 10.1128/JB.184.10.2576-2586.2002.

Caldas TD, El Yaagoubi A, Richarme G: Chaperone properties of bacterial elongation factor EF-Tu. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273 (19): 11478-11482. 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11478.

Barbier M, Owings JP, Martinez-Ramos I, Damron FH, Gomila R, Blazquez J, Goldberg JB, Alberti S: Lysine trimethylation of EF-Tu mimics platelet-activating factor to initiate Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. MBio. 2013, 4 (3): e00207-e00213. 10.3391/mbi.2013.4.3.03.

Barbier M, Oliver A, Rao J, Hanna SL, Goldberg JB, Alberti S: Novel phosphorylcholine-containing protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic infection isolates interacts with airway epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197 (3): 465-473. 10.1086/525048.

Yu H, Boucher JC, Hibler NS, Deretic V: Virulence properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lacking the extreme-stress sigma factor AlgU (sigmaE). Infect Immun. 1996, 64 (7): 2774-2781.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration West Virginia Space Grant Consortium (NASA WVSGC) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF-YU11G0). F.H.D. was supported by grants from the NASA Graduate Student Researchers Program (NNX06AH20H), NASA West Virginia Space Grant Consortium, and a post-doctoral fellowship from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (DAMRON10F0). T.R.W. was supported through the NASA WVSGC Graduate Research Fellowship. H.D.Y. was supported by NIH P20RR016477 and P20GM103434 to the West Virginia IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors’ contributions

YY designed, performed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript; FHD, TRW and CLP performed the experiments and revised the manuscript; XW and MJS revised the manuscript; HDY designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, Y., Damron, F.H., Withers, T.R. et al. Expression of mucoid induction factor MucE is dependent upon the alternate sigma factor AlgU in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol 13, 232 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-232

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-232