Abstract

Background

Although β-lactam antibiotics are heavily used in many developing countries, the diversity of β-lactamase genes (bla) is poorly understood. We screened for major β-lactamase phenotypes and diversity of bla genes among 912 E. coli strains isolated from clinical samples obtained between 1992 and 2010 from hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients.

Results

None of the isolates was resistant to carbapenems but 30% of all isolates were susceptible to cefepime, cephamycins and piperacillin-tazobactam. Narrow spectrum β-lactamase (NSBL) phenotype was observed in 278 (30%) isolates that contained blaTEM-1 (54%) or blaSHV-1 (35%) or both (11%). Extended Spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) phenotype was detected in 247 (27%) isolates which carried blaCTX-M-14 (29%), blaCTX-M-15 (24%), blaCTX-M-9 (2%), blaCTX-M-8 (4%), blaCTX-M-3 (11%), blaCTX-M-1 (6%), blaSHV-5 (3%), blaSHV-12 (5%), and bla TEM-52 (16%). Complex Mutant TEM-like (CMT) phenotype was detected in 220 (24%) isolates which carried blaTEM-125 (29%), while blaTEM-50, blaTEM-78, blaTEM-109, blaTEM − 152 and blaTEM-158 were detected in lower frequencies of between 7% and 11%. Majority of isolates producing a combination of CTX-M-15 + OXA-1 + TEM-1 exhibited resistance phenotypes barely indistinguishable from those of CMT-producers. Although 73 (8%) isolates exhibited Inhibitor Resistant TEM-like (IRT) phenotype, blaTEM-103 was the only true IRT-encoding gene identified in 18 (25%) of strains with this phenotype while the rest produced a combination of TEM-1 + OXA-1. The pAmpCs-like phenotype was observed in 94 (10%) isolates of which 77 (82%) carried blaCMY-2 while 18% contained blaCMY-1.

Isolates from urine accounted for 53%, 53%, 74% and 72% of strains exhibiting complex phenotypes such as IRT, ESBL, CMT or pAmpC respectively. On the contrary, 55% isolates from stool exhibited the relatively more susceptible NSBL-like phenotype. All the phenotypes, and majority of the bla genes, were detected both in isolates from hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients but complex phenotypes were particularly common among strains obtained between 2000 and 2010 from urine of hospitalized patients.

Conclusions

The phenotypes and diversity of bla genes in E. coli strains implicated in clinical infections in non-hospitalized and hospitalized patients in Kenya is worryingly high. In order to preserve the efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics, culture and susceptibility data should guide therapy and surveillance studies for β-lactamase-producers in developing countries should be launched.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

β-lactam antibiotics are an important arsenal of agents used against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Resistance to this class of antimicrobials is therefore of immense clinical significance. It is important to investigate the epidemiology of strains that are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics especially in Sub-Saharan Africa where treatment with alternative or more effective agents may be beyond the reach of majority of patients. Before treatment using β-lactam antibiotics is initiated, proper and timely identification of the β-lactamase phenotype is of critical importance. Failure or delay to do this may lead to therapeutic failure and death of patients [1]. In order to guide therapy and in order to understand the molecular epidemiology of β-lactamase-producers, a combination of susceptibility profiling, PCR and sequencing techniques may be required [2–4]. These techniques are not always available or affordable in resource-poor settings. Therefore, the prevalence of β-lactamases in developing countries is largely undetermined and the use of β-lactam antibiotics in such countries remains largely empiric.

Based on resistance to β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor antibiotics, bacteria strains may be conveniently categorized into various resistant phenotypes [5]. Strains exhibiting Narrow Spectrum β-lactamase Phenotypes (NSBLs) normally produce TEM-1 and/or SHV-1 enzymes that effectively degrade penicillins but are susceptible to other classes of β-lactams [6]. However, mutations on the promoter region of the gene encoding TEM-1 may result to over-production of these otherwise narrow-spectrum enzymes. This overproduction may in turn confer resistance to other classes of β-lactams besides penicillins [7–10]. Point mutations on these enzymes may also generate inhibitor resistant enzymes such as the Inhibitor Resistant TEMs (IRTs) that degrade penicillins but are not impeded by β-lactamase inhibitors such clavulanic acid or sulbactam [4, 11]. Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBLs) may also be derived from TEM- and SHV-type enzymes. ESBLs exhibit a wide hydrolytic ability to different generations of cephalosporins but remain susceptible to β-lactamase inhibitors [12]. Complex Mutant TEMs (CMTs) are also derived from TEM-1 or TEM-2 and degrade most β-lactams but are susceptible to β-lactamase inhibitors including tazobactam. The CMTs are also susceptible to cephamycins and carbapenems [13]. Plasmid–encoded AmpC (pAmpC) such as CMYs mediate resistance to most classes of β-lactams except to fourth generation cephalosporins and carbapenems [14]. The β-lactamases with the worst clinical implications are those that degrade carbapenems, the most potent class of β-lactam antibiotics available today. Some carbapenemases such as the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC) degrade virtually all classes of β-lactams [15–17]. Some carbapenemases such as metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) are however susceptible to aztreonam, a monobactam [18]. It is therefore clear that determination of β-lactamase phenotypes may not only aid the choice of agents to treat patients but may also guide the screening of bla genes and therefore save costs in surveillance studies. Understanding molecular epidemiology of bla gene is also important because majority of broad-spectrum resistant enzymes, especially the ESBLs and CMYs are encoded in conjugative plasmids that may be acquired across species barrier. Therefore, such genes have a high potential for spread via horizontal gene transfer mechanisms [19–22].

The phenotypic diversity of β-lactamase-producers in Kenya is poorly described and the diversity of bla genes has not been properly investigated [23–28]. The aim of the current study was to determine the β-lactamase phenotypes and carriage of bla genes of critical importance in E. coli obtained from blood, stool and urine obtained from hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients seeking treatment in Kenyan hospitals during an 18-year period (1992 to 2010).

Results

Phenotypic diversity of β-lactamase-producers

None of the 912 isolates tested in this study were resistant to carbapenems. Cefepime, (a fourth generation cephalosporin), cefoxitin (a cephamycin), and piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP), were effective against majority (60%) of these isolates. The NSBL-like phenotype was the most dominant phenotype in our collection and was observed in 278 (30%) of the 912 isolates compared to 73 (8%), 247 (27%), 220 (24%) and 94 (10%) of isolates found to exhibit IRT-, ESBL-, CMT and pAmpC-like phenotypes respectively, Table 1. Based on resistance phenotypes, 247 ESBL-producers fit into two sets. The first set comprised of 142 isolates exhibiting resistance to combinations of aztreonam and multiple cephalosporins including ceftazidime. The other set of 105 isolates were resistant to the same panel of antibiotics but not to ceftazidime. The 220 isolates with a CMT-like phenotype were resistant to all generations of cephalosporins but were susceptible to cephamycins and carbapenems. Resistance to all β-lactamase inhibitors including TZP was observed in 160 (73%) of the CMT-producers. Among 40 isolates with a CMT-like phenotype that had intermediate resistance to TZP, tiny ghost zones (≤ 3 mm) were observed between amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC) and ceftazidime (CAZ) and/or Cefotaxime (CTX). These isolates therefore exhibited a combination of both ESBL- and CMT-like phenotypes. The most resistant strains were those exhibiting a pAmpC-like phenotype. These 94 isolates comprising about 10% of all the isolates in our collection were resistant to most generations of cephalosporins and β-lactamase inhibitors including TZP but were susceptible to carbapenems.

Distribution of β-lactamase-producers

All the β-lactamase phenotypes reported in this study were observed in isolates from all specimen-types obtained during the 1990s and 2000s and from both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, Table 2. While majority of isolates from stool exhibited the relatively susceptible NSBL-like phenotype, isolates from urine accounted for 55%, 53%, 57% and 72% of strains with complex resistances such as IRT-, ESBL-, CMT- and pAmpC-like phenotypes respectively. Majority of isolates from hospitalized patients, especially those diagnosed with UTIs, exhibited such complex phenotypes compared to those obtained from patients seeking outpatient treatment. These complex resistances were also more common among isolates obtained in recent years (2000–2010).

Carriage of bla genes

Carriage of blaTEM- 1 or blaSHV-1 was associated with the NSBL-like phenotype in 54% and 35% of the 155 isolates exhibiting this phenotype respectively. The two genes were also found together in 11% of the NSBL-producers, Table 3. The only IRT-encoding gene identified in this study was blaTEM- 103 that was detected in 18 (25%) of the 73 isolates with an IRT-like phenotype. The other 55 (75%) of isolates with this phenotype carried a combination of blaTEM- 1+blaOXA-1 genes. Majority (78%) of the 247 isolates with an ESBL-like phenotype tested positive for CTX-M-type ESBLs. While blaCTX-M- 14 and blaCTX-M-15 were detected in 29% and 24% of these isolates respectively, blaCTX-M- 1, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-9 and blaCTX-M- 8 were detected in lower frequencies of 6%, 11%, 2% and 4% respectively, Table 3. Isolates which carried blaCTX-M- 1 alone exhibited intermediate resistances to aztreonam and cefotaxime and were fully susceptible to ceftazidime. The blaTEM-52 that was detected in 22 (16%) of ESBL-producers was the only TEM-type ESBL identified in this study. The carriage and diversity of SHV-type ESBL genes was also low in which case, only blaSHV- 5 and blaSHV- 12 ESBL-encoding genes were detected in 3% and 5% of the ESBL-producers respectively. Resistance to ceftazidime among the ESBL-producers was attributed mainly to carriage of blaCTX-M-15 or a combination of bla CTX-Ms + blaOXA- 1 + blaTEM- 1 genes. A significant proportion (39%) of isolates containing bla CTX-Ms or bla SHV -type ESBLs in the absence of blaOXA- 1 or blaTEM- 1 were susceptible to ceftazidime.

The blaTEM-125 was detected in 29% of the 124 isolates exhibiting a CMT-like phenotype and was therefore the most common CMT-encoding gene detected in this study. Other CMT genes: - bla TEM-50 , blaTEM-78, blaTEM-152 and blaTEM-158 were detected in much lower prevalences of 8%, 7%, 11%, and 8% respectively, Table 3. Carriage of CMT genes did not account for CMT-like phenotypes in 30% of isolates with this phenotype. Nine of such isolates tested positive for a combination of blaTEM-14 + blaOXA-1+blaTEM-1 while 14 strains carried a combination of blaTEM-15 + blaOXA-1+blaTEM-1. Another 15 isolates tested positive for a combination of a blaTEM-52 (a TEM-type ESBL gene), and blaOXA- 1. Production of OXA-1 and TEM-1 enzymes in the presence of CTX-M enzymes apparently masked the ESBL-phenotype that is otherwise conferred by CTX-M enzymes. Therefore, isolates producing a combination of such enzymes could hardly be distinguished from genuine CMT-producers. The blaCMY- 2 that was present in 77 (72%) of all isolates in our collection was the most common pAmpC-encoding genes detected in this study. The CMYs were also detected in strains co-producing TEM-1 and SHV-type ESBLs suggesting a possible co-evolution of penicillinases, ESBLs and AmpCs genes in the same isolate. While majority of blaOXA-1 genes were detected in strains bearing ESBL genes such as bla CTX-Ms or bla TEM-52, the blaOXA-2 were detected in strains carrying bla CMYs Table 3. None of the isolates investigated tested positive for bla- PER- like, bla ACC- like, bla VEB- like , or bla DHA- like genes.

Distribution of bla genes

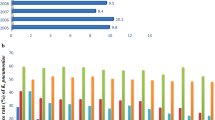

We also analyzed for the distribution of bla genes among strains obtained from different specimen-types and among those obtained from hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, Figure 1. Majority of bla genes were present in all specimen-types regardless of their clinical backgrounds. However, blaCTX-M-3 was only detected in isolates from urine while blaTEM- 78 was not detected among isolates from blood. bla TEM-109 and blaCTX-M-8 on the other hand, were exclusively detected among isolates obtained from hospitalized patients. All bla genes described in this study were found in isolates obtained from both the 1990s and 2000s except blaCMY- 1 that was exclusively detected among isolates obtained during the 2000–2010 period.

Occurrence of bla genes among isolates from different clinical backgrounds. 1a: Occurrence of bla genes among isolates from blood, stool and urine, 1b: Occurrence of bla genes among isolates from inpatient and outpatient populations: 1c: Occurrence of bla genes among isolates obtained in the 1990s and 2000s periods.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the diversity of β-lactamase genes in a large collection of E. coli from different types of clinical specimen obtained from hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients in Kenya. This study suggests that carbapenems and to a less extent, cefepime, cephamycins and piperacillin-tazobactam may still be potent against majority of the isolates investigated. Although we do not rule out that the panel of bla genes in our strains is wider than what is reported in this study, there was a general agreement between phenotypic data and the panel of bla genes detected in the strains analysed. The diversity of bla genes encountered in isolates from blood, stool and urine specimen of hospitalized patients was almost identical to the panel of genes encountered in corresponding specimens from non-hospitalized patients. This partially suggests a possible exchange of strains between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients or a flow of genes among strains from different clinical backgrounds. Based on the resistance profiles, we identify ESBL-, CMT- and pAmpC-producers as the most important set of strains whose spread in hospital and community settings should be closely monitored. If the prevalence of isolates with such highly resistant strains continues to rise, majority of β-lactam antibiotics may cease to be effective agents for management of community- and hospital-acquired infections in Kenya.

It is highly likely that heavy use of antibiotics to treat different infections, and urethral tract infections (UTI) in particular, has selected for isolates carrying multiple bla genes such as those encountered in this study. Since the antibiotic-use policy is rarely enforced in Kenya, and since most prescriptions are issued without culture and susceptibility data, β-lactam antibiotics are likely to be glossily misused. This may partially explain why complex phenotypes such as ESBL-, CMT- and pAmpC-like phenotypes were observed even among isolates from stool. The current study also shows that 41% of the isolates were resistant to at least one β-lactamase inhibitor. High resistances to inhibitor antibiotics may emerge as a result of over-reliance on amoxicillin-clavulanic acid to treat different infections in Kenya even without a valid prescription. It is however interesting to note that the prevalence of inhibitor resistant bla genes is still very low among strains exhibiting an IRT-like phenotype. Similar studies conducted in Spain reported a similar low prevalence of IRTs [29, 30]. The only true IRT reported in this study was TEM-103 while majority (75%) of isolates with an IRT-like phenotype carried a combination of blaTEM-1 + blaOXA-1. These two genes were also frequently detected in isolates exhibiting a combination of an ESBL- and CMT-like phenotypes. However, blaOXA-1 and bla TEM-1 were also detected in isolates susceptible to inhibitors. We speculate that besides conferring resistance to narrow spectrum penicillins, some TEM-1 and OXA-1 may be implicated in resistance to other classes of antimicrobials such as various generations of cephalosporins and possibly, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. These hypothesis is partially based on findings from a recent study conducted in Kenya that described novel blaOXA-1 enzymes in Salmonella strains that contain promoter mutations that confer resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics including β-lactamase inhibitors [23]. Furthermore, studies conducted elsewhere have also reported resistance to multiple β-lactam antibiotics due to promoter mutations that result to over-production of TEM-1 enzymes [30]. It is therefore important to further investigate genetic basis of resistance and the role of these otherwise narrow-spectrum β-lactamases (TEM-1 and OXA-1) in mediating resistance to advanced classes of β-lactam antibiotics in developing countries.

In the current study, we found a high diversity of CMTs, yet these enzymes have been reported only in a few countries [13]. It is possible that the ease of access to β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in Kenya without valid susceptibility data has selected for strains with CMT genes that are rarely reported from other countries. In contrast, majority of CTX-M- and SHV-type ESBLs and CMY-type pAmpCs genes identified are those with a global-like spread pattern [31–39]. Similarly, TEM-52, the only TEM-type ESBL reported in this study, is frequently reported in USA [39] and Europe [40]. The wide dissemination of genes encoding these ESBLs and pAmpCs is attributed to physical association between these genes and mobile genetic elements such as ISEcp 1, transposons and conjugative plasmids [41–43]. Such genetic affiliations further underline the potential of these genes described in this study to spread to susceptible strains through horizontal gene transfer mechanisms.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the need to combine phenotypic and molecular methods in order to understand important aspects of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in developing countries. We recommend that measures be put in place to minimize possible exchange of strains between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Prudent use of β-lactam antibiotics in developing countries should be advocated and in such countries, the existing empiric treatment regimes should be revised occasionally in order to reflect prevailing resistance phenotypes. Such measures may help to preserve the potency of β-lactam antibiotics and improve success of chemotherapy. Finally, the diversity of bla genes described in this study is relatively high and majority of genes in circulation among E. coli strains investigated have a global-like spread. We recommend that attempts be made to investigate the role of Africa and other developing countries as sources or destinations of β-lactamase-producing strains.

Methods

Bacterial strains

Between 1992 and 2010, our laboratory at the KEMRI Centre for Microbiology Research received 912 E. coli isolates from 13 health centres in Kenya. All the 912 isolates were resistant to penicillins alone (e.g. ampicillin), or a combination of penicillins and different classes of β-lactam antibiotics. These isolates were from urine (395), blood (202), stool (315) and were obtained from confirmed cases of urethral tract infections (UTIs), septicaemia and diarrhoea-like illnesses respectively. Out of the 912 isolates, 255 (28 %) were obtained between 1992 and 1999 while 657 (72 %) were obtained between 2000 and 2010. This difference was as a result of an increase in isolation rates as a result of better detection and screening techniques in recent years. These isolates were obtained from 350 patients seeking outpatient treatment and 562 were from hospitalised patients. Upon receipt, the isolates were sub-cultured on MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, U`K) and species identification done using standard biochemical tests as described before [44]. Ethical clearance to carry out this study was obtained from the KEMRI/National Ethics Committee (Approval: SSC No. 1177).

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed for all the 912 isolates using antibiotic discs (Cypress diagnostics, Langdorp, Belgium) on Mueller Hinton agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). E. coli ATCC 25922 was included as a control strain on each test occasion. Susceptibility tests were interpreted using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [45]. The antibiotics included in this panel were: - ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), oxacillin (OXA, 30 μg), amoxicillin (AML, 30 μg ), cephalothin (KF, 30 μg), cefuroxime (CXM 30 μg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30 μg) and ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg). Other antibiotics included cefepime (FEP, 30 μg), aztreonam (AZT, 30 μg), and cefoxitin (FOX, 30 μg). β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations included amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC, comprising amoxicillin 20 μg and clavulanic acid 10 μg), ampicillin/sulbactam (AMS) combinations in rations of 20 μg and 10 μg respectively, and piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) in potency ratio of 100/10 μg respectively. Imipenem (IM 30 μg) was used to test susceptibility to carbapenems.

Detection and Interpretation of β-lactamase phenotype

Two strategies were used for detection of β-lactamase phenotypes as detailed in the CLSI guidelines [45], and in other related studies [46]. The first strategy was the double-disc synergy test (m-DDST) in which the β-lactam antibiotics were placed adjacent to the amoxicillin/clavulanic (AMC) disc at inter-disc distances (centre to centre) of 20 mm. A clear extension of the edge of the disc zones towards the AMC (ghost zones or zones of synergy) was interpreted as positive for ESBL production. In the combined disc method (CDM), tests were first done using β-lactam antibiotics and then repeated using discs containing combinations of β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors. A result indicating a ≥ 5 mm increase in zone diameter for the β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor disc was interpreted as production of ESBLs [45, 46]. The results from the m-DDST and CDM methods were also used for empiric categorization of strains into NSBL-, IRT-, ESBL- CMT- and pAmpC-like β-lactamase phenotypes as detailed before [5].

PCR detection of β-lactamase genes

Preparation of DNA used as template in PCR reactions was obtained by boiling bacteria suspension from an 8 hr culture at 95 °C for 5 minutes. The supernatant was stored at -20o C until further use. Subsequent PCR amplifications were carried out in a final volume of 25 μL or 50 μL. A minimum of 5 μL of template DNA and 1 μL of 10 mM concentration of both forward and reverse primers were used in PCR reactions. Isolates from our collection that had been found to carry various bla genes in past studies [24, 27, 47], were used as positive controls in PCR screening for genes of interest. Sterile distilled water or E. coli strains susceptible to all β-lactam antibiotics were used as negative controls. PCR products were analyzed using electrophoresis in 1.5 % agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Visualization of the PCR products was done under UV light and the image recorded with the aid of a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Selection of isolates for further analysis

Isolates from each phenotype were selected for further analysis using PCR and sequencing strategies. For phenotypes with a high number of isolates (i.e. more than a hundred strains), at least 56% of the isolates were selected for further analysis. In order to minimize bias, the isolates selected from each phenotype were proportion to the total number of isolates obtained during each year of isolation (1992 to 2010). Similarly, the number of isolates selected from urine, stool and blood specimen was proportional to the total number of strains isolated from each specimen-type obtained from both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Using this criterion, 586 (64%) of the 912 isolates were selected for further analysis. Regardless of the source phenotype, all the selected isolates were investigated for carriage of the complete panel of bla genes screened for in this study.

Screening for bla genes

The strains were screened for genes frequently reported among members of family Enterobacteriaceae [11]. The list of primers used is indicated in Table 4. Consensus primers published in past studies were used for screening for blaSHV and blaTEM[48, 49], blaCTX-M[50] and blaCMY[51]. Isolates positive using blaCTX-M consensus primers were screened using primers specific for CTX-M group I to IV as described in a previous study [52]. Isolates positive using the blaCMY primers were analyzed using primers for blaCMY-1-like and blaCMY-2-like genes [53]. Detection of other β-lactamase genes was done as previously described for blaOXA-like [53, 54], blaPER-like [55] , blaACC-like [53], blaVEB-like [56], and blaDHA-like genes [57].

Sequencing

Amplicons used as template in sequencing reactions were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen Ltd., West Sussex, UK). Bi-directional sequencing of the products was done using the DiDeoxy chain termination method in ABI PRISM 310 automatic sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Consensus primers were used for sequencing except for bla CTX-M and bla OXA genes that were sequenced using group-specific primers. Translation of nucleotide sequences was done using bioinformatics tools available at the website of the National Center of Biotechnology Information on http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Alignment of the translated enzyme amino acid sequence was done against that of the wild-type using the ClustalW program on http://www.ebi.ac.uk [58]. Identification of enzyme mutations at amino acid level was determined by comparing the translated amino acid sequence with that of the wild-type enzyme published at http://www.lahey.org/studies.

Authors’ information

JK and SK are research Scientist at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI). BMG is Professor at the K.U.Leuven (Faculty of Bioscience Engineering) while PB is a Senior Research Scientist at the Veterinary and Agrochemical Research Centre (VAR).

References

Huang SS, Lee MH, Leu HS: Bacteremia due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae other than Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006, 39: 496-502.

Bush K, Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA: A functional classification scheme for beta-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995, 39: 1211-1233. 10.1128/AAC.39.6.1211.

Bush K: New beta-lactamases in gram-negative bacteria: diversity and impact on the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001, 32: 1085-1089. 10.1086/319610.

Canton R, Coque TM: The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006, 9: 466-475. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011.

Canton R, Morosini MI, de la Maza OM, de la Pedrosa EG: IRT and CMT beta-lactamases and inhibitor resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, 14 (Suppl 1): 53-62.

Jacoby GA, Medeiros AA: More extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991, 35: 1697-1704. 10.1128/AAC.35.9.1697.

Beceiro A, Maharjan S, Gaulton T, Doumith M, Soares NC, Dhanji H, Warner M, Doyle M, Hickey M, Downie G, Bou G, Livermore DM, Woodford N: False extended-spectrum {beta}-lactamase phenotype in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli associated with increased expression of OXA-1 or TEM-1 penicillinases and loss of porins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 2006-2010. 10.1093/jac/dkr265.

Tristram SG, Hawes R, Souprounov J: Variation in selected regions of blaTEM genes and promoters in Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005, 56: 481-484. 10.1093/jac/dki238.

Nelson EC, Segal H, Elisha BG: Outer membrane protein alterations and blaTEM-1 variants: their role in beta-lactam resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003, 52: 899-903. 10.1093/jac/dkg486.

Lartigue MF, Leflon-Guibout V, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Nicolas-Chanoine MH: Promoters P3, Pa/Pb, P4, and P5 upstream from bla(TEM) genes and their relationship to beta-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 4035-4037. 10.1128/AAC.46.12.4035-4037.2002.

Knox JR: Extended-spectrum and inhibitor-resistant TEM-type beta-lactamases: mutations, specificity, and three-dimensional structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995, 39: 2593-2601. 10.1128/AAC.39.12.2593.

Sirot D, Sirot J, Labia R, Morand A, Courvalin P, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Perroux R, Cluzel R: Transferable resistance to third-generation cephalosporins in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification of CTX-1, a novel beta-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987, 20: 323-334. 10.1093/jac/20.3.323.

Henquell C, Chanal C, Sirot D, Labia R, Sirot J: Molecular characterization of nine different types of mutants among 107 inhibitor-resistant TEM beta-lactamases from clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995, 39: 427-430. 10.1128/AAC.39.2.427.

Caroff N, Espaze E, Gautreau D, Richet H, Reynaud A: Analysis of the effects of −42 and −32 ampC promoter mutations in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli hyperproducing ampC. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000, 45: 783-788. 10.1093/jac/45.6.783.

da Silva RM, Traebert J, Galato D: Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a review of epidemiological and clinical aspects. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012, 663-671.

Canton R, Akova M, Carmeli Y, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, Livermore DM, Miriagou V, Naas T, Rossolini GM, Samuelsen O, Seifert H, Woodford N, Nordmann P: Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012, 18: 413-431. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x.

Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L: Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm!. Trends Mol Med. 2012, 18 (5): 263-272. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003.

Nordmann P, Poirel L: Emerging carbapenemases in Gram-negative aerobes. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002, 8: 321-331. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00401.x.

Coudron PE, Hanson ND, Climo MW: Occurrence of extended-spectrum and AmpC beta-lactamases in bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae: isolates harbor plasmid-mediated FOX-5 and ACT-1 AmpC beta-lactamases. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41 (2): 772-777. 10.1128/JCM.41.2.772-777.2003.

Dolejska M, Frolkova P, Florek M, Jamborova I, Purgertova M, Kutilova I, Cizek A, Guenther S, Literak I: CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clone B2–O25b-ST131 and Klebsiella spp. isolates in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 2784-2790. 10.1093/jac/dkr363.

Eckert C, Gautier V, Arlet G: DNA sequence analysis of the genetic environment of various blaCTX-M genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006, 57 (1): 14-23.

Escobar-Paramo P, Grenet K, Le MA, Rode L, Salgado E, Amorin C, Gouriou S, Picard B, Rahimy MC, Andremont A, Denamur E, Ruimy R: Large-scale population structure of human commensal Escherichia coli isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70: 5698-5700. 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5698-5700.2004.

Boyle F, Healy G, Hale J, Kariuki S, Cormican M, Morris D: Characterization of a novel extended-spectrum beta-lactamase phenotype from OXA-1 expression in Salmonella Typhimurium strains from Africa and Ireland. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011, 70: 549-553. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.04.007.

Kiiru J, Kariuki S, Goddeeris BM, Revathi G, Maina TW, Ndegwa DW, Muyodi J, Butaye P: Escherichia coli strains from Kenyan patients carrying conjugatively transferable broad-spectrum beta-lactamase, qnr, aac(6')-Ib-cr and 16 S rRNA methyltransferase genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66: 1639-1642. 10.1093/jac/dkr149.

Poirel L, Revathi G, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P: Detection of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55: 934-936. 10.1128/AAC.01247-10.

Pitout JD, Revathi G, Chow BL, Kabera B, Kariuki S, Nordmann P, Poirel L: Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a large tertiary centre in Kenya. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, 14: 755-759. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02030.x.

Kariuki S, Corkill JE, Revathi G, Musoke R, Hart CA: Molecular characterization of a novel plasmid-encoded cefotaximase (CTX-M-12) found in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45: 2141-2143. 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2141-2143.2001.

Kariuki S, Gilks CF, Kimari J, Muyodi J, Waiyaki P, Hart CA: Plasmid diversity of multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from children with diarrhoea in a poultry-farming area in Kenya. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997, 91: 87-94. 10.1080/00034989761355.

Miro E, Navarro F, Mirelis B, Sabate M, Rivera A, Coll P, Prats G: Prevalence of clinical isolates of Escherichia coli producing inhibitor-resistant beta-lactamases at a University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain, over a 3-year period. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 3991-3994. 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3991-3994.2002.

Perez-Moreno MO, Perez-Moreno M, Carulla M, Rubio C, Jardi AM, Zaragoza J: Mechanisms of reduced susceptibility to amoxycillin-clavulanic acid in Escherichia coli strains from the health region of Tortosa (Catalonia, Spain). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004, 10: 234-241. 10.1111/j.1198-743X.2004.00766.x.

Mendonca N, Leitao J, Manageiro V, Ferreira E, Canica M: Spread of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-producing escherichia coli clinical isolates in community and nosocomial environments in Portugal. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 1946-1955. 10.1128/AAC.01412-06.

Rodriguez-Bano J, Lopez-Cerero L, Navarro MD, de Diaz AP, Pascual A: Faecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: prevalence, risk factors and molecular epidemiology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008, 62: 1142-1149. 10.1093/jac/dkn293.

Carattoli A: Animal reservoirs for extended spectrum beta-lactamase producers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, 14 (Suppl 1): 117-123.

Livermore DM, James D, Reacher M, Graham C, Nichols T, Stephens P, Johnson AP, George RC: Trends in fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin) resistance in enterobacteriaceae from bacteremias, England and Wales, 1990–1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002, 8: 473-478. 10.3201/eid0805.010204.

Hanson ND, Moland ES, Hong SG, Propst K, Novak DJ, Cavalieri SJ: Surveillance of community-based reservoirs reveals the presence of CTX-M, imported AmpC, and OXA-30 beta-lactamases in urine isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in a U.S. community. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52: 3814-3816. 10.1128/AAC.00877-08.

Gangoue-Pieboji J, Bedenic B, Koulla-Shiro S, Randegger C, Adiogo D, Ngassam P, Ndumbe P, Hachler H: Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Yaounde, Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 3273-3277. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3273-3277.2005.

Livermore DM, Canton R, Gniadkowski M, Nordmann P, Rossolini GM, Arlet G, Ayala J, Coque TM, Kern-Zdanowicz I, Luzzaro F, Poirel L, Woodford N: CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007, 59: 165-174.

Pitout JD, Thomson KS, Hanson ND, Ehrhardt AF, Moland ES, Sanders CC: beta-Lactamases responsible for resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis isolates recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998, 42: 1350-1354.

Doi Y, Adams J, O'Keefe A, Quereshi Z, Ewan L, Paterson DL: Community-acquired extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producers, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007, 13: 1121-1123. 10.3201/eid1307.070094.

Cloeckaert A, Praud K, Doublet B, Bertini A, Carattoli A, Butaye P, Imberechts H, Bertrand S, Collard JM, Arlet G, Weill FX, Nakaya R: Dissemination of an extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase blaTEM-52 gene-carrying IncI1 plasmid in various Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from poultry and humans in Belgium and France between 2001 and 2005. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 1872-1875. 10.1128/AAC.01514-06.

Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Canica MM, Park YJ, Lavigne JP, Pitout J, Johnson JR: Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008, 61: 273-281.

Bae IK, Lee YN, Lee WG, Lee SH, Jeong SH: Novel complex class 1 integron bearing an ISCR1 element in an Escherichia coli isolate carrying the blaCTX-M-14 gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 3017-3019. 10.1128/AAC.00279-07.

Hopkins KL, Liebana E, Villa L, Batchelor M, Threlfall EJ, Carattoli A: Replicon typing of plasmids carrying CTX-M or CMY beta-lactamases circulating among Salmonella and Escherichia coli isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006, 50: 3203-3206. 10.1128/AAC.00149-06.

Cowan ST: Cowan and Steel's manual for identification of medical bacteria. 1985, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Performance standardsfor antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 15th informational supplement (M100-S15). 2007, Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne PA, USA: CLSI

Karisik E, Ellington MJ, Pike R, Warren RE, Livermore DM, Woodford N: Molecular characterization of plasmids encoding CTX-M-15 beta-lactamases from Escherichia coli strains in the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006, 58: 665-668. 10.1093/jac/dkl309.

Kariuki S, Revathi G, Corkill J, Kiiru J, Mwituria J, Mirza N, Hart CA: Escherichia coli from community-acquired urinary tract infections resistant to fluoroquinolones and extended-spectrum beta-lactams. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2007, 1: 257-262.

Arlet G, Rouveau M, Philippon A: Substitution of alanine for aspartate at position 179 in the SHV-6 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997, 152: 163-167. 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00196-1.

Arlet G, Brami G, Decre D, Flippo A, Gaillot O, Lagrange PH, Philippon A: Molecular characterisation by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of TEM beta-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995, 134: 203-208.

Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Nordmann P: Diversity of genetic environment of bla(CTX-M) genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004, 234: 201-207. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09534.x.

Winokur PL, Brueggemann A, DeSalvo DL, Hoffmann L, Apley MD, Uhlenhopp EK, Pfaller MA, Doern GV: Animal and human multidrug-resistant, cephalosporin-resistant salmonella isolates expressing a plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000, 44: 2777-2783. 10.1128/AAC.44.10.2777-2783.2000.

Pitout JD, Hossain A, Hanson ND: Phenotypic and molecular detection of CTX-M-beta-lactamases produced by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 5715-5721. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5715-5721.2004.

Hasman H, Mevius D, Veldman K, Olesen I, Aarestrup FM: beta-Lactamases among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-resistant Salmonella from poultry, poultry products and human patients in The Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005, 56: 115-121. 10.1093/jac/dki190.

Olesen I, Hasman H, Aarestrup FM: Prevalence of beta-lactamases among ampicillin-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolated from food animals in Denmark. Microb Drug Resist. 2004, 10: 334-340. 10.1089/mdr.2004.10.334.

Poirel L, Karim A, Mercat A, Le Thomas I, Vahaboglu H, Richard C, Nordmann P: Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing strain of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from a patient in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999, 43: 157-158. 10.1093/jac/43.1.157.

Kim JY, Park YJ, Kim SI, Kang MW, Lee SO, Lee KY: Nosocomial outbreak by Proteus mirabilis producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase VEB-1 in a Korean university hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004, 54: 1144-1147. 10.1093/jac/dkh486.

Verdet C, Benzerara Y, Gautier V, Adam O, Ould-Hocine Z, Arlet G: Emergence of DHA-1-producing Klebsiella spp. in the Parisian region: genetic organization of the ampC and ampR genes originating from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006, 50: 607-617. 10.1128/AAC.50.2.607-617.2006.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22: 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank staff and students attached to the CMR-WT unit lab at KEMRI and staff members of Bacteriology unit at VAR-Belgium. This work was supported by a PhD scholarship grant from the Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad (VLIR), Belgium (Grant number BBTP2007-0009-1086). This work is published with permission from the Director, KEMRI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None of the authors have competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JK designed the study, carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. SK, BM and PB designed the study and participated in manuscript write-up and review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Samuel Kariuki, Bruno M Goddeeris and Patrick Butaye contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiiru, J., Kariuki, S., Goddeeris, B.M. et al. Analysis of β-lactamase phenotypes and carriage of selected β-lactamase genes among Escherichia coli strains obtained from Kenyan patients during an 18-year period. BMC Microbiol 12, 155 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-155

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-155