Abstract

Background

EST sequencing is one of the most efficient means for gene discovery and molecular marker development, and can be additionally utilized in both comparative genome analysis and evaluation of gene duplications. While much progress has been made in catfish genomics, large-scale EST resources have been lacking. The objectives of this project were to construct primary cDNA libraries, to conduct initial EST sequencing to generate catfish EST resources, and to obtain baseline information about highly expressed genes in various catfish organs to provide a guide for the production of normalized and subtracted cDNA libraries for large-scale transcriptome analysis in catfish.

Results

A total of 17 cDNA libraries were constructed including 12 from channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and 5 from blue catfish (I. furcatus). A total of 31,215 ESTs, with average length of 778 bp, were generated including 20,451 from the channel catfish and 10,764 from blue catfish. Cluster analysis indicated that 73% of channel catfish and 67% of blue catfish ESTs were unique within the project. Over 53% and 50% of the channel catfish and blue catfish ESTs, respectively, had significant similarities to known genes. All ESTs have been deposited in GenBank. Evaluation of the catfish EST resources demonstrated their potential for molecular marker development, comparative genome analysis, and evaluation of ancient and recent gene duplications. Subtraction of abundantly expressed genes in a variety of catfish tissues, identified here, will allow the production of low-redundancy libraries for in-depth sequencing.

Conclusion

The sequencing of 31,215 ESTs from channel catfish and blue catfish has significantly increased the EST resources in catfish. The EST resources should provide the potential for microarray development, polymorphic marker identification, mapping, and comparative genome analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Catfish is the primary aquaculture species in the United States with an annual yield of over 600 million pounds [1]. While channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) accounts for the majority of commercial production, the closely related blue catfish (I. furcatus) possesses several economically important traits that have led to the production of an interspecific hybrid (channel female × blue male) recently available for commercial use [2, 3]. Channel catfish is also an important model species for the study of comparative immunology, reproductive physiology, and toxicology. The channel catfish immune system is among the best characterized of any fish species, with decades of research leading to the establishment of clonal functionally distinct lymphocyte lines, panels of specific monoclonal antibody reagents for detection of catfish immunocytes, and characterization of much of the machinery of teleost adaptive immunity (see [4] for a summary).

Genome research requires the development of a number of resources that facilitate the organization of large amounts of genetic information into units that can be easily captured, mapped, and characterized. These resources include linkage maps, physical maps, bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries, and expressed sequence tags (ESTs). While BAC libraries and physical and linkage maps have been developed for catfish [5–11], large-scale EST resources have been lacking. Expressed sequence tag (EST) sequencing and analysis is an effective means for rapid gene discovery and annotation [12–19]. Large-scale EST projects have been carried out in several teleost species to date [20–22]. A successful EST project can quickly provide a wealth of genetic information for a species, often considerably shortening the laborious process of gene isolation. Large-scale EST projects provide the raw material for expression profiling experiments utilizing microarrays based on the transcript sequences. In addition to expression analysis, ESTs are vitally important to genome research in a given species. They provide a valuable source of gene-linked markers for linkage mapping [23], can be utilized in comparative genome analysis [24, 25], and allow an assessment of gene duplications, a common phenomenon in teleost fish [26]. Sequencing the ESTs of two closely-related species such as channel catfish and blue catfish provides further benefits – gene identification is usually additive across the species, while molecular markers and gene orthologues are valuable for mapping and differentiating allelic and gene variants. Here we report the generation of 31,215 EST sequences from channel catfish and blue catfish and their potential for the development of molecular tools for mapping, genome analysis and expression profiling.

Results and discussion

cDNA library construction and sequencing of catfish ESTs

To obtain baseline information concerning the most abundantly expressed genes in catfish tissues and to capture a wide range of the transcriptome, we constructed cDNA libraries from various tissues of channel catfish and blue catfish (Table 1). These cDNA libraries were sequenced to generate the 31,215 ESTs reported here. Two of these libraries (channel catfish head kidney and spleen) have been previously reported [27, 28], but were sequenced at greater depths in this project. Twelve of the cDNA libraries were produced from channel catfish tissues, and five from blue catfish tissues. Tissue libraries were produced by pooling tissue from fish experimentally infected with Edwardsiella ictaluri and tissue from healthy, control fish, to ensure that libraries included transcripts under both healthy and diseased conditions.

EST sequencing was conducted in two phases. In phase I, 200–300 clones were sequenced from each library to provide a list of the most abundantly expressed genes. In phase II, the most abundantly expressed genes (Supplemental Table 1) were subtracted from the clones to be sequenced by screening with overgo probes, to provide a higher gene discovery rate under a restricted budget. Overgo probes were designed for 200 genes, and the probes were used for colony lifting hybridization. Subsequently, only negative clones were picked for phase II sequencing. The number of ESTs generated from each library is given in Table 1. A total of 20,451 ESTs were successfully sequenced from channel catfish, and 10,764 ESTs were sequenced from blue catfish. These ESTs have been submitted to NCBI dbEST [GenBank: BM438128–BM439194, BQ096608–BQ097456, CF261473–CF266494, CF970744–CF972299, CK401558–CK426402, and EE993123–EE993655]. Furthermore, a database, ESTIMA: Catfish, was established for free public access [29]. These ESTs represent a significant fraction of the EST resources from channel catfish and the sole publicly available transcripts from blue catfish.

Sequence assembly

A total of 31,215 clean sequences, with average length of 778 bp, were assembled using the CAP3 program [30] to evaluate the level of sequence redundancy. Blue catfish and channel catfish ESTs were assembled separately. Assembling of the 20,451 channel catfish sequences generated 1,848 clusters and 13,115 singletons. The average cluster contained 3.96 sequences. A total of 14,963 unique sequences were generated from channel catfish for this project. Assembling of the 10,764 blue catfish ESTs produced 881 clusters and 6,368 singletons with an average cluster size of 4.98 sequences. By this measure, sequencing of the blue catfish ESTs generated 7,249 unique sequences (Table 2). For the purpose of practical applications, we also performed clustering analysis by combining the ESTs from both channel catfish and blue catfish (data not presented here, but are available in the database). For instance, the clustering analysis of the ESTs from both species allowed design of microarrays with a larger set of unique sequences. For the identification of polymorphic microsatellites and SNPs, we also used ESTs from both species as our resource families were produced using the interspecific hybrids of channel catfish × blue catfish.

Sequence annotation

The putative identities of the sequenced ESTs were determined using BLASTX searches against the non-redundant (nr) database in GenBank. Of the 20,451 channel catfish ESTs, 10,859 (53%) had significant hits (cutoff E-value of e-5), while the remaining 9,592 ESTs (47%) had no significant similarity to any sequences contained in GenBank (Table 2). Similarly, of the 10,764 blue catfish ESTs, 5,456 (50.7%) had significant hits (cutoff E-value of e-5), while the remaining 5,308 ESTs (49.3%) had no significant similarity to any sequences contained in the database. While a significant fraction of ESTs could not be identified by similarity searches, our results are comparable to other EST work in fishes. The unidentified transcripts are still valuable sources of microsatellite markers, and can be furthered sequenced if determined to be important in QTL analysis or expression profiling with microarrays. Additionally, many of these currently unknown transcripts will likely be identified when they cluster with additional transcripts produced in the future.

Assessment of the sequenced catfish transcriptome

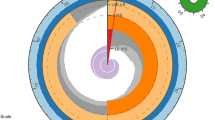

To link these catfish EST resources to a comparative genome analysis framework, we conducted systematic TBLASTN searches on all existing catfish ESTs using Tetraodon chromosome-linked proteins as queries. The TBLASTN search parameters were set to select the top catfish hit and used a relatively more stringent cutoff E-value of e-10. Approximately 50% of annotated Tetraodon genes had a significant hit against catfish ESTs (Table 3), providing a rough assessment of the percentage of the catfish transcriptome now sequenced. However, BLAST-based comparisons between sequences of the two species have several shortcomings. First, rapid intraspecific diversification of gene families within catfish and Tetraodon has obscured gene homologies between the species. Second, short and/or divergent protein sequences would be excluded with the stringent parameters used. Altogether, 6,720 unique catfish ESTs were returned as the top hit of one or more Tetraodon proteins (Fig. 1). The factors mentioned above, especially gene family diversification, could also be responsible for the modest number of catfish hits. The majority of these catfish ESTs (3,929) were hit by a single Tetraodon query. However, a sizeable proportion (22%) were hit by three or more Tetraodon queries (Table 3, Fig. 1). A survey of the catfish ESTs hit by 20 or more Tetraodon queries revealed that these represented large gene families often functioning in developmental processes. Examples of the families hitting single catfish ESTs included the protocadherin clusters, notch proteins, zinc fingers, netrin family, and Hox proteins. Analysis of the chromosomal origins of these repetitive Tetraodon queries indicates that many are clustered tightly together and have likely resulted from rapid tandem gene duplication in their local environ [31, 32]. High sequence conservation between members of these gene families may obscure their relationships with homologous families in catfish. Alternatively, transcripts representing gene family members in catfish may not have yet been sequenced.

Potential for comparative genome analysis and directed gene mapping

Comparative genome analysis is also an efficient approach for transferring linkage information from map-rich species to map-poor species [33]. In catfish, a gene-based genetic map is not yet available. In the absence of such a map, direct comparison of gene organization on chromosomes across species is difficult. However, the premise for comparative mapping is that many chromosome segments should be conserved among fish species. Of the 9,181 chromosome-linked Tetraodon proteins with significant hits on catfish ESTs, 2,529 hit a single EST. This subset should exclude many of the large intraspecific gene families and include genes with more apparent homologies. Concentrating on those ESTs with especially high p-values may further refine the set (Table 4). Associating the catfish ESTs with chromosome-linked Tetraodon proteins allows the development of a set of markers likely to be well-distributed across catfish chromosomes and which can provide anchors for a framework comparative map. Previously published analysis of microsatellite content of the ESTs described here, along with others in GenBank at the time of analysis, identified 4,855 microsatellites from 43,033 catfish ESTs. Of these, 4,103 were believed to represent unique genes [34]. Many of these microsatellites are being utilized for the construction of a gene-based linkage map for catfish. To make these markers more informative, the catfish ESTs hit by a single chromosome-linked Tetraodon query were searched for microsatellites. A total of 245 of these catfish ESTs contain a microsatellite and will aid in comparing the catfish linkage map to Tetraodon nigroviridis, providing an early assessment of genomic conservation between the two teleost species.

Two species system for identification of ancient and recent gene duplications

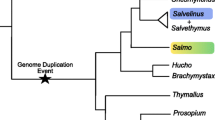

Gene duplication is a widespread phenomenon in vertebrate species and a particularly important trait of teleost fish. It has been proposed that a whole-genome duplication event occurred in the teleost lineage after its split from the tetrapod lineage, but that only a subset of the duplicated genes has been retained [35]. ESTs are a valuable tool for the identification of duplicated genes in species with and without a sequenced genome. For species with completed genome sequences, a large EST collection is invaluable for gene annotation in duplicated regions and facilitates the study of sub-functionalization among duplicated gene copies [36]. In species like catfish, where whole-genome sequencing is yet to be initiated, ESTs are important early indicators of gene copy numbers. However, comparisons of highly similar transcripts often do not allow researchers to differentiate between allelic variants and gene duplications. Using a two species system of EST sequencing and analysis, such as in channel catfish and blue catfish, can help to distinguish between these two possibilities. We surveyed the catfish EST resources for gene duplication events, applying the rationale that allelic variation within the same species should be smaller than the variation present between orthologues from different species [37]. Using this rationale, two highly similar channel catfish sequences would be considered paralogues if one of them is more closely related to a transcript from blue catfish than related to the other transcript from channel catfish. Likely instances of catfish gene duplication that included ESTs from both species were identified by BLASTN searches and then reciprocal BLASTX searches carried out. Most identified "duplications" were members of large, previously identified gene families that were the result of ancient gene duplications, i.e. similar members are present in other species such as Danio rerio. More informative were cases where all selected catfish ESTs were highly similar to the same BLASTX hit and/or gene copy number could not be predicted based on BLAST results, indicators of more recent gene duplication within catfish. Examples of these cases, where allelic variants could not be distinguished from gene paralogues based on the data from a single species alone, were subjected to phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2). The putative blue catfish orthologues provided the context necessary to differentiate between the highly similar channel catfish transcripts. The ability to utilize the ESTs from the two closely related catfish species for analysis of local gene and genome-based duplications was one of the reasons for continuing EST sequencing efforts in catfish conducted by the Joint Genome Institute (see below).

Selected examples of the ability to differentiate between catfish allelic variants and gene duplicates (paralogues) using both blue catfish and channel catfish sequences. Highly similar channel catfish sequences (Channel) and at least one blue catfish sequence (Blue) sharing the same BLAST identity were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The topological stability of the neighbor joining trees was evaluated by 1000 bootstrapping replications, and the bootstrapping values are indicated by numbers at the nodes. Channel catfish and blue catfish genes placed into the same clade indicate that the additional, related channel catfish sequence is likely a paralogue rather than an allelic variant.

Subtraction probes for normalization of cDNA libraries

Sequencing a large number of cDNA libraries widened the range of the catfish transcriptome sequenced while providing information concerning the most abundantly expressed genes in a variety of tissue types. This information is critical to ensure high numbers of unique transcripts can be obtained when sequencing a library to greater depths. To produce a list of most abundantly expressed genes for further subtraction, we conducted cluster analysis of all catfish ESTs in the dbEST database of NCBI. Clusters were sorted by size and those containing 2 or more transcripts per 10,000 sequences were selected as subtraction drivers for use during the construction of normalized/subtracted cDNA libraries to be used for a large-scale EST project (Supplemental Table 2). Through the Community Sequencing Program, a project for sequencing 300,000 clones of catfish ESTs was recently approved by the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) of the Department of Energy (DOE). Subtraction of highly abundant genes based on information gained through the current project should markedly increase the number of unique transcripts obtained by JGI sequencing, and initial sequencing and quality control determination by JGI of the subtracted cDNA libraries we produced using this strategy confirmed this assessment.

Conclusion

A large number of cDNA libraries have been made from both channel catfish and blue catfish, and they should be valuable resource for various molecular studies and for the construction of normalized cDNA libraries. This work is the first large-scale EST project in catfish. In addition to significant expansion of the channel catfish EST resources, and generation of the sole source of the blue catfish EST resource, the sequencing of 31,215 ESTs from channel catfish and blue catfish has provided the potential for the development of a number of molecular tools valuable for genome research. The EST resources will be particularly useful as sources of polymorphic markers including microsatellites and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for gene mapping. In addition, the EST resources have aided in the identification and characterization of important genes involved in immune response [38, 39]. The generated sequences are currently being utilized as reference points in comparative genome analysis and have been validated as an important tool for the assessment of gene duplications in catfish. Additionally, the ESTs served as a foundation for the creation of normalized, subtracted cDNA libraries currently being used for the sequencing of 300,000 ESTs from both ends by JGI. The development of microarrays [40, 41] and linkage maps based on the catfish EST resources will further extend their applications in research.

Methods

Tissue samples and RNA isolation

All procedures involving the handling and treatment of fish used during this study were approved by the Auburn University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AU-IACUC) prior to initiation. Channel and blue catfish were raised in troughs in the hatchery of the Auburn University Fish Genetics Hatchery for four weeks before harvesting of tissues. To create resource cDNA libraries containing a full complement of gene transcripts, including those expressed after infection, both healthy and infected catfish were used. Channel catfish and blue catfish were challenged with Edwardsiella ictaluri using procedures adapted from Dunham et al. [42]. Fish were divided into 2 groups, the non-challenged controls and the fish for challenge (N = 240). The fingerlings used for disease challenge were placed into a 150 L tank containing 1.1 × 106 E. ictaluri cells/ml for 1 h. The challenged fish were then removed and stocked into a 1000 L tank. At time of sampling, fish were euthanized with MS-222 at 300 mg/L before dissection. Tissue samples were collected from 15 control and 5 infected fish each at 24 h, 3 d, and 7 d during the challenge, pooled, quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until RNA extraction. The following tissues were collected: channel catfish gill, head kidney, trunk kidney, intestine, liver, skeletal muscle myomere, olfactory organ, ovary, pituitary, spleen, stomach, and testes; blue catfish head kidney, heart, intestine, liver and spleen. Equal tissue weights of all the control and infected pools for each tissue within a species were combined, ground to a fine powder with mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen and thoroughly mixed. A fraction of the tissue samples was used for RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated following the guanidium thiocyanate method [43] using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer's instructions. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified from total cellular RNA using the Poly(A)+ Pure kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Library construction

Initial sequencing of four catfish cDNA libraries, channel catfish brain, head kidney, skin, and spleen, was previously reported [27, 28, 44, 45]. Fifteen additional libraries from the tissues listed above were constructed here closely following protocols used previously. Briefly, the cDNA libraries were constructed using the pSPORT-1 Superscript Plasmid Cloning System from Invitrogen. This cloning system provides a vector with capacity for uni-directional cloning of cDNAs that support choices of EST sequencing from either the 5'-, or 3'-end of the transcript. In this work, all ESTs were sequenced from upstream of the transcripts (5' sequencing) to provide a longer length of ESTs. Two micrograms of Poly(A)+ RNA were used in each initial reaction. Procedures followed instructions provided by the manufacturer with the exception that ElectroMax DH12S cells (Invitrogen) were used for electroporation of the cDNA library. The quality of the cDNA libraries was determined by number of primary recombinants and average insert size. Before sequencing analysis, the primary cDNA libraries were amplified once [46]. The pooled libraries were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C.

Colony lifting hybridization and sequencing

Colony-lifting hybridization [46] was conducted using overgos as probes to reduce the sequencing redundancy of a set of 200 genes determined to be highly expressed by preliminary sequencing of the libraries. Oligonucleotides were custom made by Sigma Genosys (St. Louis, MO). Overgos were designed to overlap for 8 bases where the sense and antisense oligos pair, leaving the remaining 5' overhang for filling in using labeled nucleotides, P32-dATP and P32-dCTP [47, 48]. All the overgos were labeled in a single reaction. Overgo hybridization was conducted at 45°C overnight using conditions as previously reported [49]. The filters were washed using 2× SSC at room temperature four times for 15 minutes each. After exposure of X-ray films, bacterial plates were aligned to match the patterns of the exposed colonies on the X-ray film. Negative colonies were picked for sequencing and manually arrayed into 384 well plates containing LB with antibiotics and 10% glycerin and stored at -80°C until sequencing. Sequencing was conducted using ABI PRISM 3730 automated sequencers located in the Core Facility of Purdue University.

Sequence analysis, EST clustering, and sequence annotation

ESTs were trimmed for vector and adaptor sequences. Base calling was performed using the Phred program with quality cut-off set at 20. Sequences were assembled in CAP3 using a criteria of a minimum overlap of 70 bp sharing 90% sequence identities for clustering. Cleaned ESTs were used as queries for BLASTX searches against the nr database at NCBI and annotated based on the top, informative BLAST hit. A cutoff E-value of e-5 was used for annotation. The channel catfish and blue catfish ESTs were submitted to dbEST. A database was developed to facilitate information dissemination. ESTs were annotated using the Gene ontology (GO) terms and the results built into the database.

Catfish ESTs and comparative analysis

Chromosome-assigned proteins of Tetraodon nigroviridis as well as those from undetermined chromosome locations were downloaded from the protein database of NCBI. All proteins linked to a given Tetraodon chromosome were uploaded separately as query files onto the University of Illinois Keck Center's Gridblast server. All catfish ESTs from NCBI's dbEST were uploaded as a database on the same server. The TBLASTN search parameters were set to select the top catfish hit, using a cutoff E-value of e-10. Resulting text files were parsed to obtain Tetraodon query IDs, catfish hit IDs, and e-values and these were imported into Excel spreadsheets. Results were further sorted to separate those catfish ESTs hit by a single Tetraodon query and those hit by multiple Tetraodon queries. Catfish ESTs hit by a single Tetraodon query were uploaded to Msatfinder [50] to search for microsatellites contained in the sequences. BLASTX searches were carried out on those catfish ESTs hit by 20 or more Tetraodon queries.

Assessment of gene duplication

Channel catfish TIGR consensus (TC) sequences, composed in part by the ESTs reported here [51] were used as queries for BLASTN searches against the est_others database of NCBI, limiting the entrez query to Ictalurus. Top hits with perfect matches (E-value = 0.0) were the channel catfish sequences from the TC. If additional highly similar hits (E-value <e-25) from both channel catfish and blue catfish ESTs were present, these sequences were noted for further analysis as potential gene duplicates. Reciprocal BLASTX searches were carried out using at least three ESTs from the initial searches, with at least one of these ESTs from blue catfish. When all ESTs shared the same top BLASTX hit, they were translated, and areas of amino acid overlap identified. Phylogenetic trees were drawn by the neighbor-joining method [52] within the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA 3.0) package [53]. Data were analyzed using Poisson correction and gaps were removed by complete deletion. The topological stability of the trees was evaluated by 1,000 bootstrapping replications.

References

USDA: Catfish Production Report. National Agricultural Statistics Service USDA Washington, D.C, (July 23, 2005)

He C, Chen L, Simmons M, Li P, Kim S, Liu ZJ: Putative SNP discovery in interspecific hybrids of catfish by comparative EST analysis. Anim Genet. 2003, 34 (6): 445-8. 10.1046/j.0268-9146.2003.01054.x.

Chatakondi NG, Yant DR, Dunham RA: Commercial production and performance evaluation of channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus female × blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus male F-1 hybrids. Aquaculture. 2005, 247: 8-

Bengten E, Clem LW, Miller NW, Warr GW, Wilson M: Channel catfish immunoglobulins: repertoire and expression. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006, 30 (1–2): 77-92. 10.1016/j.dci.2005.06.016.

Waldbieser GC, Bosworth BG, Nonneman DJ, Wolters WR: A microsatellite-based genetic linkage map for channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. Genetics. 2001, 158 (2): 727-34.

Liu Z, Karsi A, Li P, Cao D, Dunham R: An AFLP-based genetic linkage map of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) constructed by using an interspecific hybrid resource family. Genetics. 2003, 165 (2): 687-94.

Xu P, Wang S, Liu L, Peatman E, Somridhivej B, Thimmapuram J, Gong G, Liu Z: Channel catfish BAC-end sequences for marker development and assessment of syntenic conservation with other fish species. Anim Genet. 2006, 37 (4): 321-6. 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01453.x.

Wang S, Xu P, Thorsen J, Zhu B, de Jong PJ, Waldbieser G, Kucuktas H, Liu ZJ: Characterization of a BAC library from channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus: indications of high rates of evolution among teleost genomes. Mar Biotechnol. 2007, in review

Xu P, Wang S, Liu L, Thorsen J, Liu ZJ: A BAC-based physical map of the channel catfish genome. Genomics. 2007,

Quiniou SM, Waldbieser GC, Duke MV: A first generation BAC-based physical map of the channel catfish genome. BMC Genomics. 2007, 8: 40-10.1186/1471-2164-8-40.

Quiniou SM, Katagiri T, Miller NW, Wilson M, Wolters WR, Waldbieser GC: Construction and characterization of a BAC library from a gynogenetic channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus. Genet Sel Evol. 2003, 35 (6): 673-683. 10.1051/gse:2003046.

Liu ZJ: Transcriptome characterization through the generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags: Factors to consider for a successful EST project. Israel J Aquaculture. 2006, 58 (4): 328-41.

Govoroun M, Le Gac F, Guiguen Y: Generation of a large scale repertoire of Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) from normalised rainbow trout cDNA libraries. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7 (1): 196-10.1186/1471-2164-7-196.

Hagen-Larsen H, Laerdahl JK, Panitz F, Adzhubei A, Hoyheim B: An EST-based approach for identifying genes expressed in the intestine and gills of pre-smolt Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). BMC Genomics. 2005, 6: 171-10.1186/1471-2164-6-171.

Rexroad CE, Rodriguez MF, Coulibaly I, Gharbi K, Danzmann RG, Dekoning J, Phillips R, Palti Y: Comparative mapping of expressed sequence tags containing microsatellites in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). BMC Genomics. 2005, 6 (1): 54-10.1186/1471-2164-6-54.

Kim TH, Kim NS, Lim D, Lee KT, Oh JH, Park HS, Jang GW, Kim HY, Jeon M, Choi BH: Generation and analysis of large-scale expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from a full-length enriched cDNA library of porcine backfat tissue. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 36-10.1186/1471-2164-7-36.

Nelson RT, Shoemaker R: Identification and analysis of gene families from the duplicated genome of soybean using EST sequences. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 204-10.1186/1471-2164-7-204.

Chini V, Rimoldi S, Terova G, Saroglia M, Rossi F, Bernardini G, Gornati R: EST-based identification of genes expressed in the liver of adult seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.). Gene. 2006, 376 (1): 102-6. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.02.010.

Deng Y, Dong Y, Thodima V, Clem RJ, Passarelli AL: Analysis and functional annotation of expressed sequence tags from the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 264-10.1186/1471-2164-7-264.

Rexroad CE, Lee Y, Keele JW, Karamycheva S, Brown G, Koop B, Gahr SA, Palti Y, Quackenbush J: Sequence analysis of a rainbow trout cDNA library and creation of a gene index. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003, 102 (1–4): 347-54. 10.1159/000075773.

Clark MS, Edwards YJ, Peterson D, Clifton SW, Thompson AJ, Sasaki M, Suzuki Y, Kikuchi K, Watabe S, Kawakami K, Sugano S, Elgar G, Johnson SL: Fugu ESTs: new resources for transcription analysis and genome annotation. Genome Res. 2003, 13 (12): 2747-53. 10.1101/gr.1691503.

Rise ML, von Schalburg KR, Brown GD, Mawer MA, Devlin RH, Kuipers N, Busby M, Beetz-Sargent M, Alberto R, Gibbs AR, Hunt P, Shukin R, Zeznik JA, Nelson C, Jones SR, Smailus DE, Jones SJ, Schein JE, Marra MA, Butterfield YS, Stott JM, Ng SH, Davidson WS, Koop BF: Development and application of a salmonid EST database and cDNA microarray: data mining and interspecific hybridization characteristics. Genome Res. 2004, 14 (3): 478-90. 10.1101/gr.1687304.

Guyomard R, Mauger S, Tabet-Canale K, Martineau S, Genet C, Krieg F, Quillet E: A Type I and Type II microsatellite linkage map of Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with presumptive coverage of all chromosome arms. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7 (1): 302-10.1186/1471-2164-7-302.

Fredslund J, Madsen LH, Hougaard BK, Nielsen AM, Bertioli D, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Schauser L: A general pipeline for the development of anchor markers for comparative genomics in plants. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 207-10.1186/1471-2164-7-207.

Varshney RK, Grosse I, Hahnel U, Siefken R, Prasad M, Stein N, Langridge P, Altschmied L, Graner A: Genetic mapping and BAC assignment of EST-derived SSR markers shows non-uniform distribution of genes in the barley genome. Theor Appl Genet. 2006, 113 (2): 239-250. 10.1007/s00122-006-0289-z.

Taylor JS, Braasch I, Frickey T, Meyer A, Van de Peer Y: Genome duplication, a trait shared by 22000 species of ray-finned fish. Genome Res. 2003, 13 (3): 382-90. 10.1101/gr.640303.

Cao D, Kocabas A, Ju Z, Karsi A, Li P, Patterson A, Liu Z: Transcriptome of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus): initial analysis of genes and expression profiles of the head kidney. Anim Genet. 2001, 32 (4): 169-88. 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2001.00753.x.

Kocabas AM, Li P, Cao D, Karsi A, He C, Patterson A, Ju Z, Dunham RA, Liu Z: Expression profile of the channel catfish spleen: analysis of genes involved in immune functions. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 2002, 4 (6): 526-36. 10.1007/s10126-002-0067-0.

Catfish EST ESTIMA. [http://titan.biotec.uiuc.edu/cgi-bin/ESTWebsite/estima_start?seqSet=catfish]

Huang X, Madan A: CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999, 9 (9): 868-77. 10.1101/gr.9.9.868.

Robinson-Rechavi M, Marchand O, Escriva H, Bardet PL, Zelus D, Hughes S, Laudet V: Euteleost fish genomes are characterized by expansion of gene families. Genome Res. 2001, 11 (5): 781-88. 10.1101/gr.165601.

Peatman E, Liu Z: CC chemokines in zebrafish: evidence for extensive intrachromosomal gene duplications. Genomics. 2006, 88 (3): 381-5. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.014.

Kayang BB, Fillon V, Inoue-Murayama M, Miwa M, Leroux S, Feve K, Monvoisin JL, Pitel F, Vignoles M, Mouilhayrat C, Beaumont C, Ito S, Minvielle F, Vignal A: Integrated maps in quail (Coturnix japonica) confirm the high degree of synteny conservation with chicken (Gallus gallus) despite 35 million years of divergence. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 101-10.1186/1471-2164-7-101.

Serapion J, Kucuktas H, Feng J, Liu Z: Bioinformatic mining of type I microsatellites from expressed sequence tags of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Mar Biotechnol (NY). 2004, 6 (4): 364-77. 10.1007/s10126-003-0039-z.

Woods IG, Wilson C, Friedlander B, Chang P, Reyes DK, Nix R, Kelly PD, Chu F, Postlethwait JH, Talbot WS: The zebrafish gene map defines ancestral vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res. 2005, 15 (9): 1307-14. 10.1101/gr.4134305.

Krushna Padhi B, Akimenko MA, Ekker M: Independent expansion of the keratin gene family in teleostean fish and mammals: an insight from phylogenetic analysis and radiation hybrid mapping of keratin genes in zebrafish. Gene. 2006, 368: 37-45. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.016.

Chapman BA, Bowers JE, Schulze SR, Paterson AH: A comparative phylogenetic approach for dating whole genome duplication events. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20 (2): 180-5. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth022.

Peatman E, Bao B, Xu P, Baoprasertkul P, Brady Y, Liu Z: Catfish CC chemokines: genomic clustering, duplications, and expression after bacterial infection with Edwardsiella ictaluri. Mol Genet Genom. 2006, 275 (3): 297-309. 10.1007/s00438-005-0081-9.

Baoprasertkul P, Peatman E, Somridhivej B, Liu Z: Toll-like receptor 3 and TICAM genes in catfish (Ictalurus sp.): species-specific expression profiles following infection with Edwardsiella ictaluri. Immunogenetics. 2006, 58 (10): 817-30. 10.1007/s00251-006-0144-z.

Li RW, Waldbieser GC: Production and utilization of a high-density oligonucleotide microarray in channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. BMC Genomics. 2006, 7: 134-10.1186/1471-2164-7-134.

Peatman E, Baoprasertkul P, Terhune J, Xu P, Nandi S, Kucuktas H, Li P, Wang S, Somridhivej B, Dunham R, Liu Z: Expression analysis of the acute phase response in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) after infection with a Gram negative bacterium. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007, doi:10.1016/j.dci.2007.03.003,

Dunham RA, Brady Y, Vinitnantharat S: Response to challenge with Edwardsiella ictaluri by channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, selected for resistance to E. ictaluri. J Appl Aquaculture. 1993, 3: 211-22. 10.1300/J028v03n03_01.

Chomczynski P, Sacchi N: Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Analyt Biochem. 1987, 162 (1): 156-59. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90021-2.

Ju Z, Karsi A, Kocabas A, Patterson A, Li P, Cao D, Dunham R, Liu Z: Transcriptome analysis of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus): genes and expression profile from the brain. Gene. 2000, 261 (2): 373-82. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00491-1.

Karsi A, Cao D, Li P, Patterson A, Kocabas A, Feng J, Ju Z, Mickett KD, Liu Z: Transcriptome analysis of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus): initial analysis of gene expression and microsatellite-containing cDNAs in the skin. Gene. 2002, 285 (1–2): 157-68. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00414-6.

Sambrook J, Frisch EF, Maniatis T: Molecular Cloning, A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1989

Bao B, Peatman E, Xu P, Li P, Zeng H, He C, Liu ZJ: The catfish liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 (LEAP-2) gene is expressed in a wide range of tissues and developmentally regulated. Mol Immunol. 2006, 43 (4): 367-77. 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.014.

Wang Y, Wang Q, Baoprasertkul P, Peatman E, Liu Z: Genomic organization, gene duplication, and expression analysis of interleukin-1beta in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Mol Immunol. 2006, 43 (10): 1653-64. 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.09.024.

Han CS, Sutherland RD, Jewett PB, Campbell ML, Meincke LJ, Tesmer JG, Mundt MO, Fawcett JJ, Kim UJ, Deaven LL, Doggett NA: Construction of a BAC contig map of chromosome 16q by two-dimensional overgo hybridization. Genome Res. 2000, 10 (5): 714-21. 10.1101/gr.10.5.714.

Msatfinder. [http://www.genomics.ceh.ac.uk/msatfinder/]

The Gene Index Project. [http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi/gireport.pl?gudb=catfish]

Saitou N, Nei M: The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987, 4 (4): 406-25.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M: MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004, 5 (2): 150-63. 10.1093/bib/5.2.150.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant from USDA NRI Animal Genome Basic Genome Reagents and Tools Program (USDA/NRICGP 2003-35205-12827). We are grateful for an equipment grant from the National Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2005-35206-15274 from the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service. We thank Renee Beam, Karen Veverica, Esau Arana, and Randell Goodman for their excellence in the production and maintenance of fish used in this study and their assistance during challenge experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

PL constructed the cDNA libraries and participated in the sequencing efforts; EP conducted bioinformatic analysis and drafted the manuscript; SW and LL conducted bioinformatic analysis and constructed the database; JF, CH, PB, PX, HK, SN, BS, JS, MS, and CT participated in the sequencing and subtraction efforts; WM, RD, YB, and JG served as co-P.I.'s of the project for the overall project design, and ZL served as the P.I. for the overall design and execution of the project, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ping Li, Eric Peatman contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2006_890_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: The most abundantly expressed genes in various tissues of catfish. This file contains two Tables with Supplemental Table 1: Abundantly expressed transcripts in catfish cDNA libraries as determined by preliminary sequencing. Overgo probes were designed based on the given clone and used for subtraction of clones picked for further sequencing, and Supplemental Table 2: Abundantly expressed transcripts (>2 copies/10,000 transcripts) in catfish EST collection in NCBI's dbEST following the current project. Approximately 40,000 catfish ESTs were assembled. Indicated clones were used as drivers in subtraction of normalized cDNA libraries currently being sequenced by JGI. (DOC 594 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Peatman, E., Wang, S. et al. Towards the ictalurid catfish transcriptome: generation and analysis of 31,215 catfish ESTs. BMC Genomics 8, 177 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-177

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-177