Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal disorder of the blood forming cells characterized by accumulation of immature blast cells in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Being a heterogeneous disease, AML has been the subject of numerous studies that focus on unraveling the clinical, cellular and molecular variations with the aim to better understand and treat the disease. Cytogenetic-risk stratification of AML is well established and commonly used by clinicians in therapeutic management of cases with chromosomal abnormalities. Successive inclusion of novel molecular abnormalities has substantially modified the classification and understanding of AML in the past decade. With the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies the discovery of novel molecular abnormalities has accelerated. NGS has been successfully used in several studies and has provided an unprecedented overview of molecular aberrations as well as the underlying clonal evolution in AML. The extended spectrum of abnormalities discovered by NGS is currently under extensive validation for their prognostic and therapeutic values. In this review we highlight the recent advances in the understanding of AML in the NGS era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

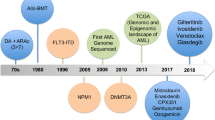

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the second most common hematological tumor and is characterized by increased proliferation and impaired maturation of early myeloid cells, leading to an accumulation of immature blood cells. The disease is now recognized as a very heterogeneous entity. Studies of chromosomal abnormalities by cytogenetics, followed by molecular genetics approach have played a significant role in deciphering the heterogeneity of AML as well as providing a profound insight into the biology of leukemia. Recurrent chromosomal and molecular defects detected at diagnosis have provided valuable prognostic information such as: response to induction chemotherapy, relapse risk and overall survival (OS). The 2008 WHO classification characterized AML based on recurrent genetic abnormalities and mutations in two oncogenes (NPM1 and CEBPA) [1]. Based on these genetic alterations, this classification system divides patients into three categories: favorable, intermediate and unfavorable. The cytogenetic profile for patients with favorable prognosis includes PML-RARA, RUNX1-RUNX1T and CBFB-MYH11 translocations. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) showing PML-RARA are treated on ATRA- and anthracycline-based or ATRA- and arsenic trioxide-based protocols, whereas the core binding factor (CBF) leukemias with RUNX1-RUNX1T and CBFB-MYH11 are treated with intensive chemotherapy involving cytarabine and are characterized by relatively favorable prognosis [2]. Cytogenetic abnormalities associated with unfavorable prognosis include monosomies of chromosomes 5 or 7, 11q23 alterations (excluding t(9;11)), inv(3), t(6;9), monosomal karyotype (defined as having greater or equal to two autosomal monosomies or a single monosomy with additional structural abnormalities) and complex karyotype (presence of three or more chromosomal abnormalities). These patients require allogeneic bone marrow transplantation during their first remission. About 50% of AML patients having cytogenetically normal karyotype (CN-AML) are categorized in the intermediate group [3]. Multiple mutations emerge in this group, which have prognostic effect determining the outcome for the therapy. The most common mutation is NPM1 in CN-AML. Patients having NPM1 mutation in the absence of a FLT3-ITD mutation have better remission rate and overall survival rate. On the other hand, CN-AML patients positive for FLT3-internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) have poor prognosis [1, 3]. Morphological, immunological as well as cytogenetic evaluation of peripheral blood and bone marrow have been the mainstay of leukemia diagnosis. Recently updated recommendations of the European Leukemia Net (ELN) for the diagnosis and management of AML has been reviewed extensively by Dohner H et al[4].

The advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has expedited the discovery of novel genetic lesions in AML. A number of re-sequencing studies in AML patients, particularly those showing normal cytogenetics, have led to the discovery of several new mutations (including DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, TET2) [5]. An effort to use the newly identified mutations, alone or in conjunction with previously characterized genetic anomalies, for gaining prognostic insights has begun. The therapy of AML has largely remained unchanged from the standard 3+7 regimen, for this reason the most important advances to current prognostic markers will be identifying those gene mutation(s) that can prospectively stratify patients who will benefit from an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). However, given the risks associated with HSCT, the identification of underlying genomic alterations in AML has a great potential for the incorporation of rationally-targeted therapies, generating a hope for improvement in treatment outcome. In this review, we have outlined the recent advances in the genomics of AML namely: the use of different NGS methodologies, novel mutations identified using NGS and their clinical impact.

Next Generation Sequencing Technologies

In the past decade, conventional Sanger sequencing method has been overtaken by several new technological advances collectively known as next generation sequencing (NGS). These technologies apply different target enrichment strategies and clonal amplification of the DNA resulting in the possibility of sequencing millions of DNA strands in parallel. This massively parallel sequencing facilitates high-throughput sequencing with a significant reduction in costs. The advent of NGS has significantly accelerated the effort to understand the molecular basis of cancers [6]. Recent development of “bench-top NGS Instruments” such as Ion Torrent PGM from Life Technologies and Mi-Seq from Illumina has been of tremendous utility in clinical settings and individual laboratories. Ion torrent PGM is based on semiconductor sequencing in which detection is done on a semiconductor chip. This technology detects the pH change due to release of hydrogen ions when a new nucleotide is inserted during synthesis [7]. Mi-Seq technology adopted the ‘sequencing by synthesis’ approach in which the template amplification and data analysis is combined in a single instrument. These instruments are smaller in size, having high throughput, high accuracy and less running time. In addition, these machines provide shorter read lengths which makes them more suitable for clinical and diagnostic applications [8]. Comprehensive reviews are available that discuss various technological aspects of NGS and its recent advancements [8–10].

AML Whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) based on NGS techniques offers the possibility to identify the complete range of genomic alterations: point mutations, indels, copy number changes, and structural rearrangements including translocations, cryptic rearrangements, inversions and complex rearrangements in the whole genome. The first whole cancer genome to be sequenced using NGS was from an AML patient in 2008 by Ley et al [11]. Genomic DNA samples from tumor and skin tissues of the cytogenetically normal AML patient were sequenced. The group performed 32.7-fold ‘haploid’ coverage (98 billion bases) for the tumor and 13.9-fold coverage (41.8 billion bases) for the normal sample, resulting in identification of 10 somatic mutations. Out of these, two recurrent somatic mutations (FLT3 and NPM1) have well-defined implications in AML. The other eight were somatic non-synonymous novel mutations. A year later, another AML patient with normal cytogenetics was sequenced by the same group. They identified sixty four somatic mutations which include mutations in the coding sequences of genes and in the conserved regulatory portions of the genome [12]. The identified mutations were validated in a larger cohort of 187 AML samples with recurring mutations found in NPM1, NRAS and IDH1 genes. In a 2010 study, Ley et al used the paired end deep sequencing approach to re-sequence the AML samples from their first study. This led to the identification of a recurrent somatic mutation in the DNA methyltransferase-3-alpha gene (DNMT3A). The frequency of DNMT3A mutation was 22% (62/281). They concluded that DNMT3A mutation is a recurrent mutation in patients with de novo AML classified into intermediate risk category [13]. Welch et al used whole genome sequencing to accurately diagnose an AML case that was referred to their institute for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The patient had complex cytogenetic profile associated with unfavorable prognosis, no detection of PML-RARA fusion transcript by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) but appeared to have APL. Whole genome sequencing was performed that led to the identification of PML-RARA fusion gene and two other fusion genes: LOXL1-PML and RARA-LOXL1. Finally, the patient was treated as APL with ATRA consolidation leading to extended remission [14]. This was an example showing how NGS based diagnosis could be useful in guiding clinicians to select the treatment path. A recent comprehensive study by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network analyzed whole genomes of 50 de novo AML cases. This study also combined whole exome and methylome analysis, and concluded that AML genomes have fewer mutations than other cancers, with an average of 13 gene mutations of which an average of 5 genes show recurrent mutations in AML [15].

In another study using whole genome sequencing, Welch et al compared the genomes of 12 AML M3 cases having known initiation event (PML-RAR) vs genomes of 12 AML M1 CN-AML patients, to identify the initiating mutation in CN-AML [16]. It was found that both AML groups have approximately same number of overall mutations, however, AML M1 genomes have mutations in NPM1, DNMT3A and IDH1 but not in AML M3. It was concluded that these mutations might act as major initiating mutations in this group. FLT3-ITD mutation was found in both genomes suggesting it to be a cooperating mutation rather than an initiating mutation. Although 13 recurrently mutated genes were found only in AML M1 samples, there were 9 recurrent mutations detected in both groups suggesting cooperation of initiating mutations can lead to AML. This study also proposed that most of the mutations in the AML genome are random events or exits as background mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell. After the initiating mutation event, cells expand with the same history of mutations to become the founding clone. This clone can acquire additional mutations to evolve into sub clones that can contribute to disease progression or relapse. Later on, Ding et al reported the clonal evolution of mutations in acute and relapsed myeloid leukemia that have been reviewed extensively elsewhere [17–19].

Transcriptome sequencing

Transcriptome sequencing is a technique that can sequence transcribed genes, coding RNA and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) that represents the complete transcriptome. The main advantage of transcriptome sequencing over WGS is that it provides: gene expression level information, identification of expressed fusion transcripts, post-transcriptional modification including alternative splicing, single nucleotide variants (SNV) and RNA editing events [20]. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a recent refinement that typically involve poly-A selection, cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription, fragmentation followed by ligation of sequencing primers [21]. Using paired-end RNA-Seq, Wen et al identified novel fusion transcript in a group of 45 AML patients that included 29 CN-AML cases, 8 cases with abnormal karyotype and 8 cases with no karyotype information [22]. The sensitivity of RNA-Seq method was shown by detection of well-known fusions in AML (RUNX-RUNX1T1, MLL-MLLT1 and MLL-MLLT3) with abnormal karyotype. Of the 134 identified fusions identified in all AML cases, seven transcript fusions were found exclusively in CN-AML. Three CIITA-DEXI fusions on chromosome 16 were detected in 14 out of 29 CN-AML patients. However, this significant finding is yet to be reproduced by other studies. Recently, Masetti et al used transcriptome sequencing to identify two novel fusion transcripts in pediatric CN-AML: CBFA2T3-GLIS2 fusion and DHH-RHEBL1 fusion [23, 24]. In a large cohort validation, CBFA2T3-GLIS2 transcript was recurrently found in pediatric CN-AML cases and predicted poor outcome [23]. The DHH-RHEBL1 transcript was detected in 40% of CBFA2T3-GLIS2-rearranged patients and conferred even worse prognosis than patients carrying CBFA2T3-GLIS-rearragment [24]. Although the role of fusion transcripts detected in this study remains to be elucidated in the context of leukemogenesis, this study has highlighted the possibility of using transcriptome sequencing for identification of chromosomal aberrations even in a large heterogeneous group of CN-AML patients, which are otherwise considered to be devoid of chromosomal rearrangements.

Exome Sequencing

The exome is the coding region of the genome and accounts for only about 1% of the whole genome. Selectively sequencing the exome is an effective and economic strategy to identify novel sequence variations in the coding region of the genome [25]. With the recent development in high-throughput sequence capture methods, exome sequencing has become an attractive and practical approach for investigating coding region variations [26, 27]. Several studies have been conducted to sequence the AML exomes and the trend is increasing. Using exome sequencing in nine AML-M5 patients, Yan et al identified mutations in 14 genes; out of which six genes having mutations previously implicated in cancers or other diseases are: DNMT3A, NSD1, GATA2, CCND3, ATP2A2 and C10orf2. The key finding in this study was the presence of three different DNMT3A variants in 23 out of 112 samples (20.5%), with individuals carrying DNMT3A mutants showing inferior prognosis as compared to ones carrying wild type DNMT3A. In addition MLL abnormalities including MLL translocations, NPM1 and NRAS mutations and FLT3 internal tandem duplications were also identified [28]. Grief et al sequenced three PML-RARA positive APL patients in leukemic and remission states. APL specific somatic mutations were identified in WT1, KRAS, HDX, and LYN that contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease [29]. Using whole exome sequencing, Grossman et al studied CN-AML patients with no mutation in NPM1, CEBPA, FLT3-ITD, IDH and MLL-PTD genes (AML index patients). Mutations in 11 genes were detected of which the most likely candidates for AML pathogenesis were: DNMT3A, BCOR, YY2 and SSRP1. The frequency of BCOR mutation was 17.1% in AML index patients, whereas the overall frequency of BCOR in unselected CN-AML was 3.8%. Mutations in BCOR were not detected in 131 AML cases having various cytogenetic abnormalities. Interestingly, 50% of the mutated BCOR patients have DNMT3A mutations suggesting that BCOR and DNMT3A might have role in the pathogenesis of CN-AML with wild type FLT3 and CEBPA [30]. Using exome sequencing, Grief et al identified novel GATA2 zinc finger 1 mutation in 2 of 5 biallelic CEBPA (biCEBPA) AML patients. Further mutational screening in 33 biCEBPA AML patients showed mutations in: GATA2 (39.4%), FLT3-ITD (18.2%), DNMT3A (9.1%), IKZF1 (6.1%). All mutations in GATA2 were found in the highly conserved N-terminal zinc finger domain (ZF1 domain) [31]. Opatz et al identified a novel N676K mutation in fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) using exome sequencing in core binding factor (CBF) leukemia [32]. This study underscores the potential use of exome sequencing in detecting novel sequence alterations even in extensively studied genes.

Targeted next generation gene sequencing

NGS techniques are continuously evolving to decrease the cost and time of sequencing, however, the amount of data generated and the effort in data analysis may not be manageable in a clinical diagnostic setting. On the other hand, a full molecular diagnostic profiling of AML may be increasingly required for clinical management of patients. For this reason, targeted gene sequencing method has gained popularity in recent years. This is a promising and effective way for targeted molecular genotyping of AML patients. Duncavage et al used targeted gene sequencing in AML cell lines to validate a method for identifying prognostically significant gene mutations including translocations, single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels on a single platform [33]. Conte et al described targeted DNA capture method using cRNA bait combined with deep sequencing for identification of 24 recurrently mutated genes in CN-AML [34]. They sequenced seven AML patients and identified 20 exonic mutations and 1 intronic mutation in known recurrently mutated genes like FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA, DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1 & 2, WT1 >and KRAS. Out of these 20 exonic mutations, 11 were single base substitutions and 9 were small indels. Two to four mutations were present in each AML patient [34]. In a recent study by Kihara et al, targeted NGS of 51 genes were performed. A total of 505 mutations in 44 genes were identified, out of which five genes: FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA, DNMT3A >and KIT, were mutated in more than 10% of the patients [35]. In addition, this comprehensive study analyzed the clinical features and prognostic impact of mutations and suggested alternative risk stratification of AML patients by inclusion of DNMT3A, MLL-PTD and TP53 genes in the proposed European Leukemia Net (ELN) system [35, 36]. With time, advancement in targeted gene sequencing may prove useful in clinical settings for the detection of known chromosomal translocations and gene mutations, requiring less procedural time and leading to correct diagnosis and risk stratification of AML patients.

Expanding spectrum of molecular genetic abnormalities in AML: Implications for prognosis and therapy

Diverse cytogenetic and molecular genetic alterations in AML have profound influence on prognostic and therapeutic decisions taken by clinicians. Cytogenetic aberrations at diagnosis have become well defined genetic biomarkers for AML classification, treatment outcome and stand as independent prognostic indicators. Core-binding factor-acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML) defined by the presence of t(8;21) or inv(16), show good outcome with intensive chemotherapy when compared with other AML subtypes or CN-AML [37]. Complex karyotype AML (CK-AML) and AML with single autosomal monosomies have poor prognosis, however AML patients having multiple autosomal monosomies or autosomal monosomies in combination with at least one chromosomal structural abnormality have extremely poor outcome [38, 39]. Further prognostic stratification of poor prognosis AML is possible with the inclusion of additional molecular alterations. For example, CK- AML with TP53 alterations had significantly lower complete remission (CR) rates and worse relapse-free survival (RFS), overall survival (OS), and event-free survival (EFS) as compared to those without TP53 alterations [40]. In CBF-AML, the presence of a KIT mutation has been shown to bring an unfavorable influence on the outcome [41]. CN-AML that lacks these cytogenetic profiles accounts for 40-50% of adult AML and is the most heterogeneous sub-group of AML. Recurrent molecular aberrations like mutations in FLT3, NPM1, and CEBPA have been useful in prognostic sub classification of CN-AML and led to the inclusion of these markers in the revised WHO classification of AML in 2008 [42]. FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITDs) are found in approximately 20% of all AML cases and between 28%-34% in CN-AML [43]. AML with FLT3-ITD show worse prognosis and is associated with shorter EFS, RFS and OS when treated with conventional chemotherapy as compared to the FLT3-ITD negative patients [3, 43]. In contrast, patients having no FLT3-ITD but mutated biCEBPA or NPM1 gene show favorable outcome [44, 45].

With the advent of NGS technologies, several new mutations have been described (table 1). Since then, a number of studies have been started with the aim to determine the mutations that contribute to disease pathogenesis and impact clinical outcomes. The following novel gene mutations (summarized in table 2) have been recently studied for their prognostic values either independently or with other known molecular abnormalities: DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, TET2 and ASXL1.

DNMT3A belongs to a family of DNA methylation enzymes with three known mammalian members namely: DNMT1, DNMT3B and DNMT3A. While DNMT1 is responsible for maintaining DNA methylation patterns through cell division, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are known for de-novo methylation [46]. DNMT3A mutation is frequent in CN-AML (29%-36%) [47–52]. The most common mutation type is a missense mutation affecting amino acid R882. AML patients showing DNMT3A mutation had worse OS and RFS [49]. DNMT3A mutations are associated with higher age, high WBC count and female gender [50]. Marcucci G et al showed differential prognostic impact of different types of DNMT3A mutations in older vs younger patients: R882 mutations are associated with adverse prognosis in older patients whereas non–R882 mutations are associated with adverse prognosis in younger CN-AML [47]. Recent studies have demonstrated that AML cells having R882H mutation show severely reduced de novo methyltransferase activity and focal hypomethylation at specific CpGs throughout their genomes. This activity has been attributed to the dominant-negative inhibition of wild type DNMT3A by R882H DNMT3A mutant that disrupts DNMT3A tetramerization [53]. A similar finding was reported earlier from a murine embryonic stem cell study that showed: Dnmt3a R878H (corresponding to human R882H) mutant protein inhibits wild-type Dnmt3a/Dnmt3b, suggesting dominant-negative effects of mutant DNMT3a [54]. Another noteworthy fact about DNMT3A mutation is its stability in the clonal evolution of AML. In NPM1-mutated AML, Kronke et al, demonstrated the loss of NPM1 mutation and the persistence on DNMT3A mutation at relapse, suggesting DNMT3A mutation as a founder event in AML pathogenesis [55]. Other studies have suggested that the stability of DNMT3A mutations during disease progression could be useful for monitoring residual disease [56]. Using conditional ablation, Challen et al have demonstrated that Dnmt3a loss in mice impairs long-term HSC differentiation, upregulates multipotency genes and downregulates differentiation factors in HSC [57]. Similarly, the role of inactivating DNMT3A mutations in AML might be a key event that shuts down differentiation of long-term HSC, leaving the possibility of a secondary oncogenic event to drive transformation into AML. A more recent study demonstrates that DNMT3A mutations precede NPM1-mutation and are found in the HSC and progenitors at diagnosis and remission. Furthermore, this study also demonstrates that pre-leukemic HSCs bearing DNMT3A mutation generate multilineage engraftment and have a competitive advantage in the immunodeficient mice-based repopulation assays [58]. These recent studies not only suggest DNMT3A mutation as a potential therapeutic target and a marker for tracking residual disease, but also as a marker for pre-leukemic clones [56, 58].

Another epigenetic modifier mutated in AML is isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) enzyme. IDH family has three different isoforms: IDH1, IDH2 and IDH3 which take part in the metabolic Krebs cycle. IDH1 is localized in the cytoplasm. IDH2 and 3 are present in mitochondria, and these three enzymes catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to alpha ketoglutarate (α-KG) [59]. IDH1 mutation was recurrently found in 16% of CN-AML [12]. IDH2 mutation was also reported in AML by candidate gene sequencing study [60]. Recurrent mutations were found in codon R132 in the case of IDH1 and at codon R140 or R172 in case of IDH2, resulting in gain of function of these enzymes which reduce α-KG to oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) [61]. 2-HG was found to be elevated in the serum of AML patients carrying IDH mutations, and the level of this oncometabolite may be useful as a diagnostic and prognostic indicator [62]. The prognostic impact of IDH mutations in AML has been investigated by several studies. In CN-AML patients, IDH mutations were associated with adverse OS and disease free survival (DFS). In CN-AML with a favorable genotype (NPM or CEBPA mutated/FLT3 wt), IDH mutations were associated with poor outcome [60, 63–65], thereby indicating a possibility of further refinement of this subgroup of CN-AML. In addition to their diagnostic and prognostic values, IDH mutations have been recognized as important therapeutic targets. Recently, Wang et al used AGI-6780, a novel and selective inhibitor of mutant IDH2 to induce differentiation in TF-1 (an erythroleukemia cell line) and primary AML cells [66]. In another study, an inhibitor of mutant IDH1, AGI-5198, has been shown to delay growth and induce differentiation of glioma cells [67], providing a proof-of-concept that IDH mutants can be therapeutically targeted. Phase I clinical trials are ongoing with two orally available, selective, potent inhibitors IDH: AG-221 (for IDH2) and AG-120 (for IDH1) [68, 69].

Mutation in the Ten-Eleven Translocation 2 (TET2) gene was found in 24% of AML and also in other myeloid cancers [70]. TET2 is the member of TET family of dioxygenases that convert 5-methyl-cytosine (5-mC) to 5-hydroxymethyl-cytosine (5-hmC) [71]. 5-hmc plays an important role in DNA demethylation. TET2 mutations were found to be significant with older age, high WBC and associated with other genetic alterations like IDH1 mutations in CN-AML. Patients with TET2 mutations have shorter OS and lower CR rate [72]. Chou et al using mutational screening of primary AML patients demonstrated TET2 mutation as an unfavorable prognostic factor in AML with intermediate cytogenetics [73]. A study with younger adult AML patients with TET2 mutations in 7.6% cases found no influence of these mutations on the response to therapy and survival. In addition, TET2 mutations were found to be mutually exclusive with IDH mutations [74]. Comparing de novo and relapse stages of AML, Wakita et al demonstrated that mutations in the epigenetic modification genes (DNMT3A, TET2 and IDH) are stably present at diagnosis and relapse suggesting them as potential biomarker in minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring [75].

Mutations in genes that effect posttranslational modification of histones have been well known in AML through MLL1 gene aberrations that include translocations and in-frame duplications [76]. Mutations in ASXL1, a member of Polycomb group of proteins have been observed frequently in myelodysplastic syndromes, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and AML [77–79]. Schnittger et al recently observed that ASXL1 mutations are more frequent in intermediate risk aberrant karyotype AML (31%) than in CN-AML (12.5%). Patients with ASXL1 mutations had shorter OS and EFS. In addition, ASXL1 mutation appeared as an independent adverse factor for OS in multivariate analysis [80]. An earlier study by Metzeler et al demonstrated that ASXL1-mutated older AML, particularly those within ELN Favorable group have adverse clinical outcomes [81]. Although the biological function of ASXL1 is not fully understood, a number of physical interactions with several proteins have been uncovered. A recent study by Abdel-Wahab et al showed that hematopoietic-specific deletion of Asxl1 resulted in an increase in the number of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) and caused a progressive myelodysplasia that was transplantable. It was shown that Asxl1 loss resulted in a global reduction of H3K27 trimethylation and aberrant expression of known hematopoietic regulators [82], raising the possibility of using H3K27 demethylase inhibitors in this situation.

Conclusion and future directions

Recent high throughput NGS approaches have uncovered a number of novel genetic alterations. The main challenge is to integrate this knowledge into clinical management of AML. As highlighted in the sections above, a number of novel molecular mutations have been validated in studies with large number of AML patients and subsequently being used in prognostic subclassification of AML. DNMT3A, TP53 and MLL-PTD mutations, for example have been recently suggested to refine the ELN classification of AML [35]. Likewise, TET2 and ASXL1 have been suggested as candidate markers for improvement of CN-AML classification in ELN scheme [72, 81]. Prospective and large-scale studies are needed to clarify the influence of many of these novel molecular aberrations in conjunction with well characterized prognosticators (NPM1, FLT3-ITD and CEBPA), on prognosis of AML.

The application of NGS in clinical settings is limited by certain challenges such as: technical difficulties in capture of GC-imbalanced targets, inaccurate reading of repetitive genomic regions and time-consuming data analysis that need special bioinformatics skills. In addition, there is a lack of uniform practice for quality assessment of NGS data. A collaborative approach among scientists, bioinformaticians and physicians coupled with creation of easily accessible and understandable database will greatly enhance and ease the clinical application of NGS.

The NGS based AML sequencing has provided several biological insights into the pathogenesis of leukemia. One key lesson derived from these studies, owing to the simultaneous detection of the whole plethora of mutations in cells, is the cancer genome evolution. Paired analysis of diagnosis and relapse samples have revealed marked changes in the genetic makeup of the cells between these points [17]. It is now understood that in AML multiple subpopulations of genetically heterogeneous cells co-exist. Competition among the subpopulations that harbor driver events thus drives the evolution of cancer either in a linear trajectory, a branched trajectory, or a combination of both, eventually shaping the final tumor composition [18, 19]. A better understanding of the AML genome evolution is needed. This will help in understanding the mechanisms of relapse, provide information about driver and cooperating events, improve the understanding of recurrent patterns of therapy resistance and suggest appropriate molecular targets.

One way to understand the pathogenic relevance of novel genetic alterations is to perform functional studies in animal models. A number of studies have taken this approach recently in evaluating the role of: Asxl1 [82], Tet2 [83] and Dnmt3a [57]. However, many recently identified genetic alterations, including novel chromosomal translocations remain to be studied in detail. Exhaustive functional studies using in vitro and in vivo experimental models are needed to understand the biological significance of these novel alterations and to distinguish driver events from passenger events. In addition, these models would pave the way for preclinical studies including testing novel therapeutic interventions.

Identification of high frequency of mutations in potential epigenetic regulators (DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, ASXL1, and UTX) is particularly interesting. It remains imperative that the mechanisms underlying epigenetic dysregulation and its consequences be clearly understood. This may allow us to better use the available methylation and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors based on the underlying genetic abnormalities that have shown some clinical success in the treatment of myeloid leukemias [77, 84]. Many new drugs that target aberrant but reversible epigenetic modifications have been recently tested in preclinical leukemia models and leukemia cell lines: Schenk et al recently demonstrated that inhibitors of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1, also known as KDM1A) epigenetically reprogram the cells to make them sensitive to ATRA induced differentiation in AML [85]. A study by Deshpande et al demonstrated how inhibition of histone-methyltransferase DOT1L, that is the driving force behind MLL-AF6 fusion leukemias, resulted in inhibition of MLL-AF6-transformed cells [86]. Stewart et al demonstrated how targeting bromodomain containing protein 4 (BRD4) in combination with daunorubicin inhibited growth of DNMT3A/NPM1-mutated leukemia cells [87]. These studies stress the potential of targeted therapies against the expanding spectrum of mutations in AML.

The progressive enhancement in the molecular characterization of AML holds promise for undertaking the more precise and targeted therapeutic strategies leading to possibly better treatment outcomes. In addition to this, inclusion of NGS based deep sequencing methods in molecular diagnostics workup has the potential to realize the goals of personalized medicine.

Abbreviations

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- NGS:

-

next generation sequencing

- OS:

-

overall survival

- APL:

-

Acute promyelocytic leukemia

- CBF:

-

core binding factor

- CN-AML:

-

cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia

- WGS:

-

Whole genome sequencing

- DNMT3A:

-

DNA methyltransferase-3-alpha gene

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- TCGA:

-

the Cancer Genome Atlas

- ncRNA:

-

non-coding RNA

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA Sequencing

- biCEBPA:

-

biallelic CEBPA mutation

- ZF1 domain:

-

zinc finger domain

- FLT3:

-

fms-related tyrosine kinase 3

- CBF:

-

core binding factor

- SNVs:

-

single nucleotide variants

- ELN:

-

European Leukemia Net

- CK-AML:

-

complex karyotype

- MK:

-

monosomal karyotype

- RFS:

-

relapse-free survival

- DFS:

-

disease free survival

- CR:

-

complete remission

- OS:

-

overall survival

- EFS:

-

event-free survival

- IDH:

-

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- α-KG:

-

alpha ketoglutarate

- 2-HG:

-

2-hydroxyglutarate

- TET2:

-

Ten-Eleven Translocation 2

- 5-mC:

-

5-methyl-cytosine

- 5-hmC:

-

5-hydroxymethyl-cytosine

- MRD:

-

minimal residual disease

- HSPC:

-

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

- HDAC:

-

histone deacetylase

References

Hasserjian RP: Acute myeloid leukemia: advances in diagnosis and classification. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2013, 35 (3): 358-366. 10.1111/ijlh.12081.

Grimwade D, Hills R: Independent prognostic factors for AML outcome. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2009, 385-395.

Ghanem H, Tank N, Tabbara IA: Prognostic implications of genetic aberrations in acute myelogenous leukemia with normal cytogenetics. American journal of hematology. 2012, 87 (1): 69-77. 10.1002/ajh.22197.

Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, Burnett AK, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson RA, et al: Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010, 115 (3): 453-474. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358.

Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013, 368 (22): 2059-2074.

Koboldt DC, Steinberg KM, Larson DE, Wilson RK, Mardis ER: The next-generation sequencing revolution and its impact on genomics. Cell. 2013, 155 (1): 27-38. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.006.

Morey M, Fernandez-Marmiesse A, Castineiras D, Fraga JM, Couce ML, Cocho JA: A glimpse into past, present, and future DNA sequencing. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2013, 110 (1-2): 3-24. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.024.

Loman NJ, Misra RV, Dallman TJ, Constantinidou C, Gharbia SE, Wain J, Pallen MJ: Performance comparison of benchtop high-throughput sequencing platforms. Nature biotechnology. 2012, 30 (5): 434-439. 10.1038/nbt.2198.

Liu L, Li Y, Li S, Hu N, He Y, Pong R, Lin D, Lu L, Law M: Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2012, 251364

Quail MA, Smith M, Coupland P, Otto TD, Harris SR, Connor TR, Bertoni A, Swerdlow HP, Gu Y: A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC genomics. 2012, 13: 341-10.1186/1471-2164-13-341.

Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, Fulton B, McLellan MD, Chen K, Dooling D, Dunford-Shore BH, McGrath S, Hickenbotham M, et al: DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008, 456 (7218): 66-72. 10.1038/nature07485.

Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Chen K, Koboldt DC, Fulton RS, Delehaunty KD, McGrath SD, et al: Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. The New England journal of medicine. 2009, 361 (11): 1058-1066. 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840.

Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, Payton JE, Baty J, Welch J, et al: DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2010, 363 (25): 2424-2433. 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143.

Welch JS, Westervelt P, Ding L, Larson DE, Klco JM, Kulkarni S, Wallis J, Chen K, Payton JE, Fulton RS, et al: Use of whole-genome sequencing to diagnose a cryptic fusion oncogene. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011, 305 (15): 1577-1584. 10.1001/jama.2011.497.

Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368 (22): 2059-2074.

Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, Miller CA, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, Wartman LD, Lamprecht TL, Liu F, Xia J, et al: The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012, 150 (2): 264-278. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023.

Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, Miller CA, Koboldt DC, Welch JS, Ritchey JK, Young MA, Lamprecht T, McLellan MD, et al: Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012, 481 (7382): 506-510. 10.1038/nature10738.

Landau D, Carter S, Getz G, Wu C: Clonal evolution in hematological malignancies and therapeutic implications. Leukemia. 2014, 28 (1): 34-43. 10.1038/leu.2013.248.

Rebecca AB, Charles S: The evolution of the unstable cancer genome. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2014, 24:

Welch JS, Link DC: Genomics of AML: clinical applications of next-generation sequencing. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2011, 30-35.

McGettigan P: Transcriptomics in the RNA-seq era. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2013, 17 (1): 4-11. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.12.008.

Wen H, Li Y, Malek SN, Kim YC, Xu J, Chen P, Xiao F, Huang X, Zhou X, Xuan Z, et al: New fusion transcripts identified in normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia. PloS one. 2012, 7 (12): e51203-10.1371/journal.pone.0051203.

Masetti R, Pigazzi M, Togni M, Astolfi A, Indio V, Manara E, Casadio R, Pession A, Basso G, Locatelli F: CBFA2T3-GLIS2 fusion transcript is a novel common feature in pediatric, cytogenetically normal AML, not restricted to FAB M7 subtype. Blood. 2013, 121 (17): 3469-3472. 10.1182/blood-2012-11-469825.

Masetti R, Togni M, Astolfi A, Pigazzi M, Manara E, Indio V, Rizzari C, Rutella S, Basso G, Pession A, et al: DHH-RHEBL1 fusion transcript: a novel recurrent feature in the new landscape of pediatric CBFA2T3-GLIS2-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2013, 4 (10): 1712-1720.

Wang Z, Liu X, Yang BZ, Gelernter J: The Role and Challenges of Exome Sequencing in Studies of Human Diseases. Frontiers in genetics. 2013, 4: 160-

Biesecker LG: Exome sequencing makes medical genomics a reality. Nature genetics. 2010, 42 (1): 13-14. 10.1038/ng0110-13.

Mamanova L, Coffey AJ, Scott CE, Kozarewa I, Turner EH, Kumar A, Howard E, Shendure J, Turner DJ: Target-enrichment strategies for next-generation sequencing. Nature methods. 2010, 7 (2): 111-118. 10.1038/nmeth.1419.

Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, Pan CM, Lu G, Shen Y, Shi JY, Zhu YM, Tang L, Zhang XW, et al: Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nature genetics. 2011, 43 (4): 309-315. 10.1038/ng.788.

Greif PA, Yaghmaie M, Konstandin NP, Ksienzyk B, Alimoghaddam K, Ghavamzadeh A, Hauser A, Graf A, Krebs S, Blum H, et al: Somatic mutations in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) identified by exome sequencing. Leukemia. 2011, 25 (9): 1519-1522. 10.1038/leu.2011.114.

Grossmann V, Tiacci E, Holmes AB, Kohlmann A, Martelli MP, Kern W, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Klein HU, Dugas M, Schindela S, et al: Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of BCOR in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. 2011, 118 (23): 6153-6163. 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365320.

Greif PA, Dufour A, Konstandin NP, Ksienzyk B, Zellmeier E, Tizazu B, Sturm J, Benthaus T, Herold T, Yaghmaie M, et al: GATA2 zinc finger 1 mutations associated with biallelic CEBPA mutations define a unique genetic entity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012, 120 (2): 395-403. 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403220.

Opatz S, Polzer H, Herold T, Konstandin NP, Ksienzyk B, Zellmeier E, Vosberg S, Graf A, Krebs S, Blum H, et al: Exome sequencing identifies recurring FLT3 N676K mutations in core-binding factor leukemia. Blood. 2013, 122 (10): 1761-1769. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476473.

Duncavage EJ, Abel HJ, Szankasi P, Kelley TW, Pfeifer JD: Targeted next generation sequencing of clinically significant gene mutations and translocations in leukemia. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2012, 25 (6): 795-804. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.29.

Conte N, Varela I, Grove C, Manes N, Yusa K, Moreno T, Segonds-Pichon A, Bench A, Gudgin E, Herman B, et al: Detailed molecular characterisation of acute myeloid leukaemia with a normal karyotype using targeted DNA capture. Leukemia. 2013, 27 (9): 1820-1825. 10.1038/leu.2013.117.

Kihara R, Nagata Y, Kiyoi H, Kato T, Yamamoto E, Suzuki K, Chen F, Asou N, Ohtake S, Miyawaki S, et al: Comprehensive analysis of genetic alterations and their prognostic impacts in adult acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia. 2014

Döhner H, Estey E, Amadori S, Appelbaum F, Büchner T, Burnett A, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson R, et al: Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010, 115 (3): 453-474. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358.

Dombret H, Preudhomme C, Boissel N: Core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML): is high-dose Ara-C (HDAC) consolidation as effective as you think?. Current opinion in hematology. 2009, 16 (2): 92-97. 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283257b18.

Orozco JJ, Appelbaum FR: Unfavorable, complex, and monosomal karyotypes: the most challenging forms of acute myeloid leukemia. Oncology. 2012, 26 (8): 706-712.

Breems DA, Van Putten WL, De Greef GE, Van Zelderen-Bhola SL, Gerssen-Schoorl KB, Mellink CH, Nieuwint A, Jotterand M, Hagemeijer A, Beverloo HB, et al: Monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a better indicator of poor prognosis than a complex karyotype. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008, 26 (29): 4791-4797. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0259.

Rucker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, Kayser S, Teleanu V, Kett H, Habdank M, Kugler CM, Holzmann K, Gaidzik VI, et al: TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood. 2012, 119 (9): 2114-2121. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375758.

Paschka P: Core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Seminars in oncology. 2008, 35 (4): 410-417. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.011.

Martelli MP, Sportoletti P, Tiacci E, Martelli MF, Falini B: Mutational landscape of AML with normal cytogenetics: biological and clinical implications. Blood reviews. 2013, 27 (1): 13-22. 10.1016/j.blre.2012.11.001.

Dohner H, Gaidzik VI: Impact of genetic features on treatment decisions in AML. Hematology / the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2011, 36-42.

Preudhomme C, Sagot C, Boissel N, Cayuela JM, Tigaud I, de Botton S, Thomas X, Raffoux E, Lamandin C, Castaigne S, et al: Favorable prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA). Blood. 2002, 100 (8): 2717-2723. 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0990.

Verhaak RG, Goudswaard CS, van Putten W, Bijl MA, Sanders MA, Hugens W, Uitterlinden AG, Erpelinck CA, Delwel R, Lowenberg B, et al: Mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): association with other gene abnormalities and previously established gene expression signatures and their favorable prognostic significance. Blood. 2005, 106 (12): 3747-3754. 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2168.

Shih AH, Abdel-Wahab O, Patel JP, Levine RL: The role of mutations in epigenetic regulators in myeloid malignancies. Nature reviews Cancer. 2012, 12 (9): 599-612. 10.1038/nrc3343.

Marcucci G, Metzeler K, Schwind S, Becker H, Maharry K, Mrózek K, Radmacher M, Kohlschmidt J, Nicolet D, Whitman S, et al: Age-related prognostic impact of different types of DNMT3A mutations in adults with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012, 30 (7): 742-750. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2092.

Ostronoff F, Othus M, Ho PA, Kutny M, Geraghty DE, Petersdorf SH, Godwin JE, Willman CL, Radich JP, Appelbaum FR, et al: Mutations in the DNMT3A exon 23 independently predict poor outcome in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a SWOG report. Leukemia. 2013, 27 (1): 238-241. 10.1038/leu.2012.168.

Ribeiro AF, Pratcorona M, Erpelinck-Verschueren C, Rockova V, Sanders M, Abbas S, Figueroa ME, Zeilemaker A, Melnick A, Lowenberg B, et al: Mutant DNMT3A: a marker of poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012, 119 (24): 5824-5831. 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367961.

Roller A, Grossmann V, Bacher U, Poetzinger F, Weissmann S, Nadarajah N, Boeck L, Kern W, Haferlach C, Schnittger S, et al: Landmark analysis of DNMT3A mutations in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2013, 27 (7): 1573-1578. 10.1038/leu.2013.65.

Renneville A, Boissel N, Nibourel O, Berthon C, Helevaut N, Gardin C, Cayuela JM, Hayette S, Reman O, Contentin N, et al: Prognostic significance of DNA methyltransferase 3A mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association. Leukemia. 2012, 26 (6): 1247-1254. 10.1038/leu.2011.382.

Thol F, Damm F, Lüdeking A, Winschel C, Wagner K, Morgan M, Yun H, Göhring G, Schlegelberger B, Hoelzer D, et al: Incidence and prognostic influence of DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011, 29 (21): 2889-2896. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4894.

Russler-Germain DA, Spencer DH, Young MA, Lamprecht TL, Miller CA, Fulton R, Meyer MR, Erdmann-Gilmore P, Townsend RR, Wilson RK, et al: The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers. Cancer cell. 2014, 25 (4): 442-454. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.010.

Kim SJ, Zhao H, Hardikar S, Singh AK, Goodell MA, Chen T: A DNMT3A mutation common in AML exhibits dominant-negative effects in murine ES cells. Blood. 2013, 122 (25): 4086-4089. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-483487.

Kronke J, Bullinger L, Teleanu V, Tschurtz F, Gaidzik VI, Kuhn MW, Rucker FG, Holzmann K, Paschka P, Kapp-Schworer S, et al: Clonal evolution in relapsed NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013, 122 (1): 100-108. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479188.

Hou HA, Kuo YY, Liu CY, Chou WC, Lee MC, Chen CY, Lin LI, Tseng MH, Huang CF, Chiang YC, et al: DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: stability during disease evolution and clinical implications. Blood. 2012, 119 (2): 559-568. 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369934.

Challen G, Sun D, Jeong M, Luo M, Jelinek J, Berg J, Bock C, Vasanthakumar A, Gu H, Xi Y, et al: Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nature genetics. 2012, 44 (1): 23-31.

Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, Chen WC, Brandwein JM, Gupta V, Kennedy JA, Schimmer AD, Schuh AC, Yee KW, et al: Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014, 506 (7488): 328-333. 10.1038/nature13038.

Andronesi OC, Rapalino O, Gerstner E, Chi A, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Sorensen AG, Rosen BR: Detection of oncogenic IDH1 mutations using magnetic resonance spectroscopy of 2-hydroxyglutarate. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013, 123 (9): 3659-3663. 10.1172/JCI67229.

Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Margeson D, Holland KB, Whitman SP, Becker H, Schwind S, et al: IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010, 28 (14): 2348-2355. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730.

Walker A, Marcucci G: Molecular prognostic factors in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Expert review of hematology. 2012, 5 (5): 547-558. 10.1586/ehm.12.45.

DiNardo CD, Propert KJ, Loren AW, Paietta E, Sun Z, Levine RL, Straley KS, Yen K, Patel JP, Agresta S, et al: Serum 2-hydroxyglutarate levels predict isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013, 121 (24): 4917-4924. 10.1182/blood-2013-03-493197.

Nomdedeu J, Hoyos M, Carricondo M, Esteve J, Bussaglia E, Estivill C, Ribera JM, Duarte R, Salamero O, Gallardo D, et al: Adverse impact of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in primary AML: experience of the Spanish CETLAM group. Leukemia research. 2012, 36 (8): 990-997. 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.03.019.

Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Habdank M, Kronke J, Bullinger L, Spath D, Kayser S, Zucknick M, Gotze K, et al: IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010, 28 (22): 3636-3643. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762.

Green C, Evans C, Hills R, Burnett A, Linch D, Gale R: The prognostic significance of IDH1 mutations in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia is dependent on FLT3/ITD status. Blood. 2010, 116 (15): 2779-2782. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270926.

Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E, Straley K, Kernytsky A, Liu W, Gliser C, et al: Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science. 2013, 340 (6132): 622-626. 10.1126/science.1234769.

Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C, Tsoi J, Clark O, Oldrini B, Komisopoulou E, et al: An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013, 340 (6132): 626-630. 10.1126/science.1236062.

IDH mutant specific inhibitors AG-221 and AG-120. [http://www.agios.com/pipeline-idh.php]

FROM AACR-Haematological cancer: AG-221, first-in-class IDH2 mutation inhibitor shows promise. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2014, 11 (6): 302-

Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, James C, Trannoy S, Masse A, Kosmider O, Le Couedic JP, Robert F, Alberdi A, et al: Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. The New England journal of medicine. 2009, 360 (22): 2289-2301. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069.

Solary E, Bernard OA, Tefferi A, Fuks F, Vainchenker W: The Ten-Eleven Translocation-2 (TET2) gene in hematopoiesis and hematopoietic diseases. Leukemia. 2013

Metzeler KH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Margeson D, Becker H, Curfman J, Holland KB, Schwind S, Whitman SP, et al: TET2 mutations improve the new European LeukemiaNet risk classification of acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011, 29 (10): 1373-1381. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7742.

Chou WC, Chou SC, Liu CY, Chen CY, Hou HA, Kuo YY, Lee MC, Ko BS, Tang JL, Yao M, et al: TET2 mutation is an unfavorable prognostic factor in acute myeloid leukemia patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics. Blood. 2011, 118 (14): 3803-3810. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339747.

Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Spath D, Habdank M, Kohne CH, Germing U, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Held G, Horst HA, Haase D, et al: TET2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis of the AML study group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012, 30 (12): 1350-1357. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2886.

Wakita S, Yamaguchi H, Omori I, Terada K, Ueda T, Manabe E, Kurosawa S, Iida S, Ibaraki T, Sato Y, et al: Mutations of the epigenetics-modifying gene (DNMT3a, TET2, IDH1/2) at diagnosis may induce FLT3-ITD at relapse in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2013, 27 (5): 1044-1052. 10.1038/leu.2012.317.

Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA: MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007, 7 (11): 823-833. 10.1038/nrc2253.

Abdel-Wahab O, Levine R: Mutations in epigenetic modifiers in the pathogenesis and therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013, 121 (18): 3563-3572. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-451781.

Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, Bonansea J, Cervera N, Carbuccia N, Lagarde A, Prebet T, Nezri M, Sainty D, et al: Mutations of polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. British journal of haematology. 2009, 145 (6): 788-800. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07697.x.

Tefferi A: Novel mutations and their functional and clinical relevance in myeloproliferative neoplasms: JAK2, MPL, TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH and IKZF1. Leukemia. 2010, 24 (6): 1128-1138. 10.1038/leu.2010.69.

Schnittger S, Eder C, Jeromin S, Alpermann T, Fasan A, Grossmann V, Kohlmann A, Illig T, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, et al: ASXL1 exon 12 mutations are frequent in AML with intermediate risk karyotype and are independently associated with an adverse outcome. Leukemia. 2013, 27 (1): 82-91. 10.1038/leu.2012.262.

Metzeler K, Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher M, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, Nicolet D, Whitman S, Wu Y-Z, Schwind S, et al: ASXL1 mutations identify a high-risk subgroup of older patients with primary cytogenetically normal AML within the ELN Favorable genetic category. Blood. 2011, 118 (26): 6920-6929. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-368225.

Abdel-Wahab O, Gao J, Adli M, Dey A, Trimarchi T, Chung Y, Kuscu C, Hricik T, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lafave L, et al: Deletion of Asxl1 results in myelodysplasia and severe developmental defects in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013, 210 (12): 2641-2659. 10.1084/jem.20131141.

Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, Abdel-Wahab O, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lobry C, Figueroa M, Vasanthakumar A, Patel J, Zhao X, et al: Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer cell. 2011, 20 (1): 11-24. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.001.

Altucci L, Clarke N, Nebbioso A, Scognamiglio A, Gronemeyer H: Acute myeloid leukemia: therapeutic impact of epigenetic drugs. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2005, 37 (9): 1752-1762. 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.019.

Schenk T, Chen WC, Gollner S, Howell L, Jin L, Hebestreit K, Klein HU, Popescu AC, Burnett A, Mills K, et al: Inhibition of the LSD1 (KDM1A) demethylase reactivates the all-trans-retinoic acid differentiation pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Nature medicine. 2012, 18 (4): 605-611. 10.1038/nm.2661.

Deshpande AJ, Chen L, Fazio M, Sinha AU, Bernt KM, Banka D, Dias S, Chang J, Olhava EJ, Daigle SR, et al: Leukemic transformation by the MLL-AF6 fusion oncogene requires the H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1l. Blood. 2013, 121 (13): 2533-2541. 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465120.

Stewart HJ, Horne GA, Bastow S, Chevassut TJ: BRD4 associates with p53 in DNMT3A-mutated leukemia cells and is implicated in apoptosis by the bromodomain inhibitor JQ1. Cancer medicine. 2013, 2 (6): 826-835. 10.1002/cam4.146.

Genomic and Epigenomic Landscapes of Adult De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013, 368 (22): 2059-2074.

Prebet T, Boissel N, Reutenauer S, Thomas X, Delaunay J, Cahn JY, Pigneux A, Quesnel B, Witz F, Thepot S, et al: Acute myeloid leukemia with translocation (8;21) or inversion (16) in elderly patients treated with conventional chemotherapy: a collaborative study of the French CBF-AML intergroup. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009, 27 (28): 4747-4753. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0674.

Renneville A, Boissel N, Nibourel O, Berthon C, Helevaut N, Gardin C, Cayuela JM, Hayette S, Reman O, Contentin N, et al: Prognostic significance of DNA methyltransferase 3A mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association. Leukemia. 2012, 26 (6): 1247-1254. 10.1038/leu.2011.382.

Yamaguchi S, Iwanaga E, Tokunaga K, Nanri T, Shimomura T, Suzushima H, Mitsuya H, Asou N: IDH1 and IDH2 mutations confer an adverse effect in patients with acute myeloid leukemia lacking the NPM1 mutation. European journal of haematology. 2014

Chotirat S, Thongnoppakhun W, Promsuwicha O, Boonthimat C, Auewarakul CU: Molecular alterations of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) metabolic genes and additional genetic mutations in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia patients. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2012, 5: 5-10.1186/1756-8722-5-5.

Chao HY, Jia ZX, Chen T, Lu XZ, Cen L, Xiao R, Jiang NK, Ying JH, Zhou M, Zhang R: IDH2 mutations are frequent in Chinese patients with acute myeloid leukemia and associated with NPM1 mutations and FAB-M2 subtype. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2012, 34 (5): 502-509. 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2012.01422.x.

Grossmann V, Haferlach C, Nadarajah N, Fasan A, Weissmann S, Roller A, Eder C, Stopp E, Kern W, Haferlach T, et al: CEBPA double-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia harbours concomitant molecular mutations in 76.8% of cases with TET2 and GATA2 alterations impacting prognosis. British journal of haematology. 2013, 161 (5): 649-658. 10.1111/bjh.12297.

Weissmann S, Alpermann T, Grossmann V, Kowarsch A, Nadarajah N, Eder C, Dicker F, Fasan A, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, et al: Landscape of TET2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012, 26 (5): 934-942. 10.1038/leu.2011.326.

Kosmider O, Delabesse E, de Mas VM, Cornillet-Lefebvre P, Blanchet O, Delmer A, Recher C, Raynaud S, Bouscary D, Viguie F, et al: TET2 mutations in secondary acute myeloid leukemias: a French retrospective study. Haematologica. 2011, 96 (7): 1059-1063. 10.3324/haematol.2011.040840.

Pratcorona M, Abbas S, Sanders MA, Koenders JE, Kavelaars FG, Erpelinck-Verschueren CA, Zeilemakers A, Lowenberg B, Valk PJ: Acquired mutations in ASXL1 in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence and prognostic value. Haematologica. 2012, 97 (3): 388-392. 10.3324/haematol.2011.051532.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Saudi Arabia, for funding the strategic grant (09-BIO693-03) and KACST project APR-34-13.

Declarations

Publication charges for this article have been funded by the Center of Excellence in Genomic Medicine Research, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah.

This article has been published as part of BMC Genomics Volume 16 Supplement 1, 2015: Selected articles from the 2nd International Genomic Medical Conference (IGMC 2013): Genomics. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcgenomics/supplements/16/S1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FA, AMI and SA wrote the manuscript. MF, MIN, TAK, MHA and MG edited the final version.

All authors read and approved the final version of MS.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ilyas, A.M., Ahmad, S., Faheem, M. et al. Next Generation Sequencing of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Influencing Prognosis. BMC Genomics 16 (Suppl 1), S5 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-16-S1-S5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-16-S1-S5