Abstract

Background

An array of experimental models have been developed in the small model organisms C. elegans, S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster for the study of various neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and expanded polyglutamine diseases as exemplified by Huntington's disease (HD) and related ataxias. Genetic approaches to determine the nature of regulators of the disease phenotypes have ranged from small scale to essentially whole genome screens. The published data covers distinct models in all three organisms and one important question is the extent to which shared genetic factors can be uncovered that affect several or all disease models. Surprisingly it has appeared that there may be relatively little overlap and that many of the regulators may be organism or disease-specific. There is, however, a need for a fully integrated analysis of the available genetic data based on careful comparison of orthologues across the species to determine the real extent of overlap.

Results

We carried out an integrated analysis using C. elegans as the baseline model organism since this is the most widely studied in this context. Combination of data from 28 published studies using small to large scale screens in all three small model organisms gave a total of 950 identifications of genetic regulators. Of these 624 were separate genes with orthologues in C. elegans. In addition, 34 of these genes, which all had human orthologues, were found to overlap across studies. Of the common genetic regulators some such as chaperones, ubiquitin-related enzymes (including the E3 ligase CHIP which directly links the two pathways) and histone deacetylases were involved in expected pathways whereas others such as the peroxisomal acyl CoA-oxidase suggest novel targets for neurodegenerative disease therapy

Conclusions

We identified a significant number of overlapping regulators of neurodegenerative disease models. Since the diseases have, as an underlying feature, protein aggregation phenotypes it was not surprising that some of the overlapping genes encode proteins involved in protein folding and protein degradation. Interestingly, however, some of the overlapping genes encode proteins that have not previously featured in targeted studies of neurodegeneration and this information will form a useful resource to be exploited in further studies of potential drug-targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite major advances, debilitating neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases as exemplified by Huntington's disease (HD) and related ataxias afflict millions worldwide and remains a significant and unresolved burden facing ageing populations. Many genetic factors including specific causative mutations have been identified but therapies for these debilitating and eventually fatal disorders are lacking. These disorders are associated with the unifying theme of accumulation of toxic, misfolded protein aggregates or inclusion bodies followed by progressive neuronal dysfunction, eventual neuronal loss and death. In many cases the mutations in disease-specific proteins that lead to protein aggregation have been indentified and there is growing evidence that the cellular protein quality control systems are an underlying common denominator of these diseases [1]. In different individuals, the susceptibility to disease-related mutations and the time of onset of age-related neurodegeneration differ significantly suggesting the importance of additional genetic factors or genetic variation [2]. Despite this, relatively few genetic factors shared between neurodegenerative diseases have been identified so far.

Knowledge of genetic regulators of neurodegeneration is important not only for an understanding of potential neuroprotective mechanisms but for the identification of potential new drug targets. The use of small model organisms with short generation times such as C. elegans, S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster, has facilitated testing of hypotheses to illuminate a prospective cellular cause of protein-misfolding diseases like HD, PD, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and AD or neuroprotective mechanisms against neurodegeneration [3, 4]. Disease models in these organisms have also allowed screening of potential genetic modifiers of the late-onset cellular and behavioural phenotypes. Screening can be performed by molecular, genetic and chemical manipulations of gene function, i.e. using mutagenesis (deletion libraries, transposon based insertion), transgenic overexpression of exogenous human misfolding disease-related proteins, or RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown to determine the loss- or gain-of-function phenotypes. Previous studies have ranged from the examination of the effects of genetic manipulation of small number of targeted genes to whole genome screens. In addition, a wide range of disease models has been examined. For example in C. elegans, the most widely studied model organism in this context, multiple tissue-specific transgenic models manifesting pathological phenotypes that faithfully recapitulate many cellular and molecular pathologies of complex neurodegenerative disease processes have been used [5, 6]. These models have been based on muscular or neuronal expression of aggregation-prone proteins such as mutant tau, superoxide dismutase (SOD1), α-synuclein, polyQ constructs, Huntingtin fragment and toxic amyloid beta 1-42 (Aβ1-42) [7], and has allowed identification of modifiers and cellular processes of α-synuclein inclusion formation [8, 9], polyQ [10] and mutant SOD1 aggregation [11], α-synuclein and polyQ-induced toxicity [12, 13] and tau-induced pathology [14]. The model organism approach and the various disease models that have been studied have been extensively reviewed in recent years and will not be described further here [5, 6, 15–20].

It might be expected that common features should underlie the different pathways that lead to or protect from the phenotypes in diverse neurodegenerative diseases. One key question of interest, therefore, is the extent to which the model organism studies have identified common genetic regulators of neurodegenerative disease. While chaperone proteins involved in protein folding have emerged as common factors [1] it has appeared that relatively few overlapping genetic regulators have been identified from genetic screens using different models. For example the same group using a whole genome RNAi screen in C. elegans models of both polyQ and α-synuclein aggregation reported only a single gene overlap from a large number of hits identified [9, 10]. Use of RNAi screens in Drosophila cell lines with similar huntingtin polyQ models identified 21 [21] and 126 [22] regulators respectively. Only three of these identified regulators overlapped between the two studies. In addition, only two regulators from the Drosophila cell line studies overlapped with those found in an assay for polyQ aggregation in human cells [23] and had opposite effects. In another study, regulation of toxicity due to expression of either α-synuclein or a huntingtin fragment in yeast was found to involve non-overlapping sets of genes [24]. One problem in comparing across all screens is the different disease models that have, for example, used toxicity in all or only in specific neurons or alternatively protein aggregate formation in either neurons or muscle as the disease phenotype [5, 6, 17]. An initial analysis of different screens based on the biological function of identified genes did indicate the role of common and differing functional classes of modifier genes involved in various cellular process including regulation of protein homeostasis, vesicular traffic and transcriptional control [17]. A significant problem in understanding the commonality of genetic regulators is the need for careful matching of protein orthologues across the three model species and this has not been carried out systematically.

We have set out to use data from published genetic screens in C. elegans, S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster to generate an integrated data set of genetic regulators of neurodegeneration. In order to do this we have used C. elegans as the reference point since this organism is most applicable for large scale screens and has been very widely used for study of neurodegenerative mechanisms. For C. elegans and D. melanogaster we have focussed on screens at the whole organism level as these have the additional possibility of identifying non-cell autonomous factors. The aim of this study was to give an improved indication of shared genetic factors and to provide a resource for future studies on neurodegeneration and neuroprotection.

Results and Discussion

A series of papers were collated in which genetic approaches were used to identify regulators of neurodegenerative models in S. cerevisiae and diverse whole organism models in C. elegans and D. melanogaster (Figure 1). As well as medium and large scale screens we also included examples of targeted small scale genetic studies of candidate genes to allow inclusion of other regulators. There are additional candidate gene studies or screens on cells lines from Drosophila for example [21, 22, 25] that have not been included. Data from the published literature was first used to compile a list of genes identified as regulators in various neurodegeneration models in C. elegans (Additional file 1). For studies in D. melanogaster and S. cerevisiae, lists of the gene regulators was compiled and then the existence and identity of any C. elegans orthologues was examined for each genetic regulator using the Princeton Protein Orthology Database [26]. Confirmation of the existence of single or multiple potential orthologues generated lists of the C. elegans orthologues of genetic regulators of neurodegeneration from studies in D. melanogaster (Additional file 2) and S. cerevisiae (Additional file 3). From this analysis of a total of 950 identified genetic modifiers of neurodegeneration, 675 were found to have orthologues that could be identified in the C. elegans genome (Table 1). The genes that did not have identifiable orthologues in C. elegans are likely to be yeast- or fly-specific or simply not represented in the C. elegans genome.

From the combined lists, a total of 624 distinct genes encoding genetic regulators were identified (Additional file 4). An initial analysis of the genetic modifiers based on cellular function was carried out. As described previously from this type of analysis [17] it could be seen that the genes covered a wide range of cellular functions covering 17 different classes of biological function (Figure 2). There was, however, a concentration of genes in certain functional classes. Genes involved in protein folding (e.g. heat shock proteins), protein degradation and autophagy were discovered across multiple disease models. Genes involved in transcriptional regulation were identified across all the polyQ and tau-disease models. It was noteworthy that the α-synuclein disease models produced a particular concentration of regulators functional in vesicular transport (e.g. rab-1) although these did appear, albeit less frequently, in studies on other disease models.

Functional profiling of genetic modifiers identified in diverse screens. Comparative analysis of modifiers identified in worm (Ce) models of polyQ, tau, SOD and α-synuclein aggregation, yeast (Sc) models of misfolded α-synuclein and Htt toxicity and fly (Dm) models of misfolded tau and polyQ toxicity from diverse screens reveals that the identified modifier genes function in a wide variety of biological processes as defined in the original studies. The blue filled box indicates that one or more genes in this category were identified. The number of the study indicated refers to the numbering in Table 1.

Of more interest was the potential identification of specific genes with overlapping modifying roles in different disease models and model organisms. Within the set of distinct C. elegans orthologues we found 34 that had been indentified in more than one study. These are shown in Table 2 and in an expanded version with additional information in Additional file 5. Significantly, all of these genes have human orthologues (Additional file 5). The overlapping regulators fell into several different functional classes (Table 3) based on their classification in the original studies.

A recent study has extended the identification of suppressors of polyQ aggregation in C. elegans [10] by examining whether knock down of their human orthologues would suppress aggregation of mutant huntingtin in a human cell line. Of the 177 human orthologues, 26 inhibited aggregation in the HK293 cells supporting the idea that genetic regulators identified in C. elegans would have a conserved function relevant for a human model [23]. Three of the human suppressors correspond to the overlapping regulators in Table 2 (hsp-1, cct-4 and cct-5) and a fourth was an additional subunit of TCP-1 (cct-2).

Many but not all of the overlapping genes in Table 2 are known to be expressed in adult neurons in C. elegans where they could, therefore, have a physiological role in regulating neurodegeneration. This is clearly an important consideration as some of the worm disease models are based on aggregate formation in muscle rather than neuronal cells. It should be noted that the data available in WormBase on the cellular expression of worm proteins is variable and so the question of neuronal expression is uncertain for some of the regulators. Two genes, bli-3 and phi-49 have, however, non-neuronal and restricted cell type expression. This may suggest that they may be unlikely to be physiological regulators of neurodegeneration in the worm but alternatively they could, for example, affect release of extracellular factors that act on neurons.

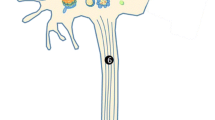

The overlapping gene set included regulators identified in more than one study but only using the same or similar type of disease model in a single species (Table 2). Others, however, had been identified in multiple models and/or species. Amongst the latter were, unsurprisingly, members of families with functions related to protein folding such as hsp-1, hsf-1, dnj-13, cct-4, and cct-5 which have key roles in proteostasis [27]. In addition, three genes encoding enzymes involved in ubiquitination, chn-1, ubc-8, and let-70 were identified in more than one study. The mammalian orthologues, CHIP and Ube2D2 respectively, of chn-1 (an E3 ligase) and let-70 (E2 conjugating enzyme) are known to interact directly [28, 29] as are CHIP and p97 (cdc-48.1) [30]. Interestingly, CHIP also provides a further link between ubiquitination and protein folding pathways based on its known interactions with and ability to ubiquitinate Hsc70 and HSF1 (Figure 3). These data would put CHIP at a key point in two pathways that modify neurodegeneration. The idea that CHIP is a key player in the regulation of neurodegeneration is reinforced by the evidence that it has been shown to ubiquitinate α-synuclein [31] and ataxin-1 [32] and to stimulate the ubiquitin ligase activity of the PD gene product Parkin [33]. In addition, CHIP has a neuroprotective role in the neurotoxicity caused by over-expression of ataxin-1 in a fly model [32]. Taken together with the screens included here [14, 34] in which CHIP orthologues were found to modify neurodegeneration models including those based on tau-induced pathology, polyQ-related disorders and α-synuclein over-expression, it appears that CHIP could play a key protective role in multiple neurodegenerative diseases.

The diagram shows known binary protein-protein interactions between the molecular chaperone and ubiquitin-related overlapping regulators in Table 2. The interactions are included if they were identified between orthologues of the proteins from any species and are shown labelled with the names of the human orthologues with those involved in protein folding (chaperones) in blue and those in ubiquitin-related pathways in red. The human orthologues and their corresponding C. elegans orthologues are as follows: HSF1, hsf-1; Hsc70, hsp-1; DnaJB5, dnj-13; CHIP, chn-1; p97, cdc-48.1; Ube2D2, let-70.

Another significant functional grouping in the shared modifiers is the three histone deacetylases, sir-2.1, hda-1 and sin-3 which were identified in both polyQ and α-synuclein disease models in flies and worms. The mammalian orthologues of hda-1 (human HDAC1) and sin3 (human SIN3B) interact directly and function as part of a protein complex to repress gene transcription [35, 36]. A selective study on histone deacetylases in C. elegans showed opposing effects of different deacetylases but loss of either hda-1 or sir-2.1 exacerbated neurodegeneration due to polyQ toxicity [37]. Overexpression of sir-2.1 had been suggested to increase longevity in C. elegans [38] leading to widespread study of the potential anti-aging effects of the related sirtuins in many species including a possible role in the effects of calorie-restriction on life span in C. elegans [39] and other species [40]. It might be thought that its neuroprotective effect could be related to its general effect on ageing. Recent work has, however, largely eliminated a role for sir-2.1 in increasing lifespan following the removal of an additional unrelated mutation in the worm strain studied. In contrast, a neuroprotective effect on a polyQ model of neurodegeneration remained associated with sir-2.1 overexpression [41]. A neuroprotective role of calorie restriction in C. elegans has also been shown to be mediated by sir-2.1 [42]. SIRT1, the mammalian orthologues of sir-2.1 and other histone deacetylases have been well established to regulate neurodegeneration and have been suggested as potential drug targets [43, 44]. The use of histone deacetylases inhibitors is currently being examined for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases but there are concerns about the potential detrimental effects of these inhibitors [43, 45].

The epsilon isoform of the 14-3-3 proteins (CG31196) was identified in screens in the fly as a regulator of polyQ-mediated neurotoxicity. This fly protein has two worm orthologues (ftt-2 and par-5). One of these, ftt-2 has also been shown to be neuroprotective when over-expressed in a worm model of α-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity [46]. It has been shown that 14-3-3 proteins may increase lifespan and can interact with sir-2.1 [47, 48]. Recent work [49] has suggested that the neuroprotective role of 14-3-3 proteins in mammalian cells may be due to inhibition of the apoptotic factor Bax [49].

A screen of genetic regulators of toxicity due to a mutant huntingtin fragment in S. cerevisiae identified Bna4 (kynurenine 3-monooxygenase) as the most potent suppressor [50]. Orthologues of Bna4 exist in D. melanogaster (CG1555) and in C. elegans (R07B7.5) but they were not identified in any of the screens in these organisms in Table 1. Nevertheless, recent studies have identified neuroprotective effects of inhibition or loss of kynurenine 3-monooxygenase and the kynurenine pathway in general in a Huntington's disease model in D. melanogaster and both Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease models in mice [51, 52] suggesting a similar role in different organisms. Significantly, the study in D. melanogaster [52] also showed that loss of function in the tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase gene (vermillion) the first enzyme in the kynurenine pathway was neuroprotective. The C. elegans orthologue of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (C28H8.11) was one of the suppressors of α-synuclein inclusion formation identified in a genome wide screen in C. elegans [9]. These two enzymes can be regarded, therefore, as general regulators of neurodegeneration across species and diseases.

Recent work has implicated defects in autophagy as a contributor to neurodegeneration and the process of autophagy as a key protective mechanism in preventing neurodegeneration [53–56]. Within the list of regulatory genes identified none encoded direct components of the autophagy machinery. Interestingly, however, the list of overlapping genes included sir-2.1 orthologues of which are involved in signalling pathways that control autophagy and thereby lifespan [53, 57]. In addition, rab-1 was discovered in genetic screens as a regulator of α-synuclein-mediated protein aggregation in a yeast model and is also effective in neuroprotection in worms and flies [58, 59]. The orthologues of rab-1 (specifically Rab1a in mammals) were recently shown to rescue an autophagy defect due to α-synuclein overexpression in mammalian cells and in Drosophila implicating the Rab1a isoform in autophagosome formation [54].

A genome-wide screen for genes that modify toxicity of Aβ1-42 in S. cerevisiae has identified 23 suppressor and 17 enhancer genes [60]. Of these 12 have human and 11 C. elegans orthologues. Three of the conserved yeast suppressors (YAP1802, INP52 and SLA1) have known functions in endocytosis. In addition, the human orthologues (PICALM, SYNJ1 and SH3KBP1) have been found from genome-wide association studies to be risk factors themselves (PICALM) or alternatively (SYNJ1 and SH3KBP1) to interact with known risk factors for Alzheimer's disease [61, 62]. Examination of the effect the C. elegans orthologues (unc-11, unc-26 and Y44E3A.4) in a worm Aβ1-42 model confirmed that the endocytic genes had protective roles in this species [60]. Interestingly, a protective role for unc-11 and unc-26 has previously been identified in a C. elegans huntingtin polyQ disease model [13]. Overall these studies suggest an important role for clathrin-mediated endocytosis in regulation of toxicity in different disease models.

The other overlapping modifiers in Table 2 do not fit obviously into related functional classes but some of these genes may be generally significant. One that is noteworthy is the Acyl-CoA oxidase that was identified in all three model species in different disease models. The single orthologue in yeast, pox1, was identified as a regulator of α-synuclein toxicity in yeast [24]. The fly orthologue FBgn0027572 (CG5009) was identified in a genome wide screen for regulators of polyQ ataxin-3-mediated neurodegeneration in the eye where its over-expression suppressed the phenotype [63]. In addition, CG5009 also suppressed tau-mediated toxicity. Search of the Princeton Protein Orthology Database identifies seven orthologues of the yeast and fly genes in C. elegans (C48B4.1, F08A8.2, F08A8.3, F08A8.4, F08A8.1, F59F4.1, F25C8.1) and an additional orthologue has been postulated (F58F9.7) [64]. It is possible that all of the predicted worm acyl CoA oxidases could have overlapping functions. Of these orthologues, however, only the worm F59F4.1 gene was identified as a regulator of α-synuclein aggregate formation in a large scale RNAi screen where its knock down enhanced aggregation [65] suggesting that this particular orthologue has a non-redundant role. Interestingly in the fly model CG5009 was functionally linked to protein folding mechanisms based on an examination of effects of its over-expression on defects due to expression of a dominant negative form of Hsp70 [63]. The effect of over-expression of CG5009 was to enhance the defect, an effect that was also seen with the Hsp70 co-chaperone DnaJ-1. A single orthologue (ACOX1) is present in mammals where it is localised to peroxisomes and functions in β-oxidation of fatty acids. The potential importance of peroxisomes in general and more specifically acyl-CoA oxidase in neuroprotection is highlighted by the Zellweger class of peroxisomal biogenesis disorders in which there are severe neurological abnormalities. Mutations in ACOX1 (OMIM number 609751) are liked to clinical conditions which include a range of neurological problems. The function of acyl-CoA oxidase in fatty acid metabolism and its widespread tissue distribution results, however, in a range of clinical symptoms in conditions of reduced enzyme activity [66]. Acyl CoA oxidase has not previously been given serious consideration as regulator of neurodegeneration in specifically-targeted studies.

Conclusions

An integrated analysis of data available from genetic screens of regulators of neurodegeneration in various disease models in yeast, fly and worms has identified 34 shared regulators. This is a higher number than was expected from previous studies. There are some additional candidate gene studies and screens on cell lines that were not included in this analysis and so the number could potentially be increased by incorporation of these. Several of the shared regulators identified here are members of classes of genes encoding proteins involved in protein folding and/or ubiquitin-dependent pathways. These form a group of 6 directly interacting proteins with the E3 ligase CHIP linking the two functional pathways. Other shared regulators that have received previous attention in targeted studies on neuroprotection included histone deacetylases and 14-3-3 proteins. Interestingly, other shared regulators emerged which have not previously been considered as key regulators of neurodegeneration including acyl-CoA oxidase. The role in neuroprotection of acyl-CoA oxidase, in particular, clearly warrants further study.

Methods

Literature Mining

Studies using genetic approaches to study genetic regulators of neurodegenerative disease models in C. elegans, S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster were identified using key word searches in PubMed http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez). The identified published literature was manually curated to compile a collection of experimentally delineated genetic modifiers of protein aggregation, misfolding and neurodegeneration in C. elegans, S. cerevisiae and D. melanogaster. Files containing full lists of modifiers in the online supplemental materials of the papers were converted and imported into Microsoft Excel.

Orthologue search

Individual worm orthologues of yeast and fly modifier genes were identified by searching the Princeton Protein Orthology Database (P-POD version 4) (http://ortholog.princeton.edu/findorthofamily.html) [26] and use of OrthoMCL [67] to determine the appropriate orthologues. These identifications were further checked and refined by consulting WormBase (http://www.wormbase.org/) using the "best Blast score", Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (http://www.yeastgenome.org) and FlyBase (http://flybase.org) and use of BLAST searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Information on the list of modifiers was further refined by conducting search queries in the bioinformatic interfaces at WormBase [WormBase Web site, available at http://www.wormbase.org, release version WS224, April, 2011], Biomart [http://www.biomart.org/], and GExplore 1.1 [http://genome.sfu.ca/gexplore/].

Analysis of protein-protein interactions

Known protein-protein interactions amongst orthologues of the overlapping genetic regulators was identified by manual searches using the protein interaction databases BioGrid, IntAct, MINT, the Human Protein Reference Database and by literature searches on PubMed

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer's disease

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- HD:

-

Huntington's disease: PD: Parkinson's disease

- polyQ:

-

polyglutamine

- SOD:

-

superoxide dismutase.

References

Voisine C, Pedersen JS, Morimoto RI: Chaperone networks: Tipping the balance in protein folding diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2010, 40 (1): 12-20. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.007.

Gandhi S, Wood NW: Genome-wide association studies: the key to unlocking neurodegeneration?. Nat Neurosci. 2010, 13 (7): 789-794. 10.1038/nn.2584.

Kearney JA: Genetic modifiers of neurological disease. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2011, 21 (3): 349-353. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.12.007.

Brignull HR, Morley JF, Morimoto RI: The stress of misfolded proteins: C. elegans models for neurodegenerative disease and aging. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 594: 167-189. 10.1007/978-0-387-39975-1_15.

Teschendorf D, Link C: What have worm models told us about the mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction in human neurodegenerative diseases?. Mol Neurodegener. 2009, 4 (1): 1-13. 10.1186/1750-1326-4-1.

Harrington AJ, Hamamichi S, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA: C. elegans as a model organism to investigate molecular pathways involved with Parkinson's disease. Dev Dyn. 2010, 239 (5): 1282-1295.

Link CD: Expression of human beta-amyloid peptide in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995, 92 (20): 9368-9372. 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9368.

Kuwahara T, Koyama A, Gengyo-Ando K, Masuda M, Kowa H, Tsunoda M, Mitani S, Iwatsubo T: Familial Parkinson Mutant α-Synuclein Causes Dopamine Neuron Dysfunction in Transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281 (1): 334-340.

van Ham TJ, Thijssen KL, Breitling R, Hofstra RMW, Plasterk RHA, Nollen EAA: C. elegans Model Identifies Genetic Modifiers of α-Synuclein Inclusion Formation During Aging. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4 (3): e1000027-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000027.

Nollen EA, Garcia SM, van Haaften G, Kim S, Chavez A, Morimoto RI, Plasterk RH: Genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies previously undescribed regulators of polyglutamine aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101 (17): 6403-6408. 10.1073/pnas.0307697101.

Wang J, Farr GW, Hall DH, Li F, Furtak K, Dreier L, Horwich AL: An ALS-Linked Mutant SOD1 Produces a Locomotor Defect Associated with Aggregation and Synaptic Dysfunction When Expressed in Neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5 (1): e1000350-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000350.

Faber PW, Voisine C, King DC, Bates EA, Hart AC: Glutamine/proline-rich PQE-1 proteins protect Caenorhabditis elegans neurons from huntingtin polyglutamine neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99 (26): 17131-17136. 10.1073/pnas.262544899.

Parker JA, Metzler M, Georgiou J, Mage M, Roder JC, Rose AM, Hayden MR, Neri C: Huntingtin-interacting protein 1 influences worm and mouse presynaptic function and protects Caenorhabditis elegans neurons against mutant polyglutamine toxicity. J Neurosci. 2007, 27 (41): 11056-11064. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1941-07.2007.

Kraemer BC, Burgess JK, Chen JH, Thomas JH, Schellenberg GD: Molecular pathways that influence human tau-induced pathology in Caenorhabditis elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2006, 15 (9): 1483-1496. 10.1093/hmg/ddl067.

Rubinsztein D: Functional genomics approaches to neurodegenerative diseases. Mammalian Genome. 2008, 19 (9): 587-590. 10.1007/s00335-008-9130-0.

Lessing D, Bonini NM: Maintaining the brain: insight into human neurodegeneration from Drosophila melanogaster mutants. Nat Rev Genet. 2009, 10 (6): 359-370. 10.1038/nrg2563.

van Ham TJ, Breitling R, Swertz MA, Nollen EAA: Neurodegenerative diseases: Lessons from genome-wide screens in small model organisms. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2009, 1 (8-9): 360-370.

Moloney A, Sattelle DB, Lomas DA, Crowther DC: Alzheimer's disease: insights from Drosophila melanogaster models. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010, 35 (4): 228-235. 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.11.004.

Johnson JR, Jenn RC, Barclay JW, Burgoyne RD, Morgan A: Caenorhabditis elegans: a useful tool to decipher neurodegenerative pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010, 38 (2): 559-563. 10.1042/BST0380559.

Mallik M, Lakhotia SC: Modifiers and mechanisms of multi-system polyglutamine neurodegenerative disorders: lessons from fly models. J Genet. 2010, 89 (4): 497-526. 10.1007/s12041-010-0072-4.

Doumanis J, Wada K, Kino Y, Moore AW, Nukina N: RNAi screening in Drosophila cells identifies new modifiers of mutant huntingtin aggregation. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4 (9): e7275-10.1371/journal.pone.0007275.

Zhang S, Binari R, Zhou R, Perrimon N: A genomewide RNA interference screen for modifiers of aggregates formation by mutant Huntingtin in Drosophila. Genetics. 2010, 184 (4): 1165-1179. 10.1534/genetics.109.112516.

Teuling E, Bourgonje A, Veenje S, Thijssen K, de Boer J, van der Velde J, Swertz M, Nollen E: Modifiers of mutant huntingtin aggregation: functional conservation of C. elegans-modifiers of polyglutamine aggregation. PLoS Curr. 2011, 3: RRN1255-

Willingham S, Outeiro TF, DeVit MJ, Lindquist SL, Muchowski PJ: Yeast Genes That Enhance the Toxicity of a Mutant Huntingtin Fragment or α-Synuclein. Science. 2003, 302 (5651): 1769-1772. 10.1126/science.1090389.

Schulte J, Sepp KJ, Wu C, Hong P, Littleton JT: High-content chemical and RNAi screens for suppressors of neurotoxicity in a Huntington's disease model. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6 (8): e23841-10.1371/journal.pone.0023841.

Heinicke S, Livstone MS, Lu C, Oughtred R, Kang F, Angiuoli SV, White O, Botstein D, Dolinski K: The Princeton Protein Orthology Database (P-POD): a comparative genomics analysis tool for biologists. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2 (8): e766-10.1371/journal.pone.0000766.

Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M: Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011, 475 (7356): 324-332. 10.1038/nature10317.

Soss SE, Yue Y, Dhe-Paganon S, Chazin WJ: E2 conjugating enzyme selectivity and requirements for function of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286 (24): 21277-21286. 10.1074/jbc.M111.224006.

van Wijk SJ, de Vries SJ, Kemmeren P, Huang A, Boelens R, Bonvin AM, Timmers HT: A comprehensive framework of E2-RING E3 interactions of the human ubiquitin-proteasome system. Mol Syst Biol. 2009, 5: 295-

Hatakeyama S, Matsumoto M, Yada M, Nakayama KI: Interaction of U-box-type ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) with molecular chaperones. Genes Cells. 2004, 9 (6): 533-548. 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00742.x.

Kalia LV, Kalia SK, Chau H, Lozano AM, Hyman BT, McLean PJ: Ubiquitinylation of alpha-synuclein by carboxyl terminus Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) is regulated by Bcl-2-associated athanogene 5 (BAG5). PLoS ONE. 2011, 6 (2): e14695-10.1371/journal.pone.0014695.

Al-Ramahi I, Lam YC, Chen HK, de Gouyon B, Zhang M, Perez AM, Branco J, de Haro M, Patterson C, Zoghbi HY, et al: CHIP protects from the neurotoxicity of expanded and wild-type ataxin-1 and promotes their ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281 (36): 26714-26724. 10.1074/jbc.M601603200.

Imai Y, Soda M, Hatakeyama S, Akagi T, Hashikawa T, Nakayama KI, Takahashi R: CHIP is associated with Parkin, a gene responsible for familial Parkinson's disease, and enhances its ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol Cell. 2002, 10 (1): 55-67. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00583-X.

Branco J, Al-Ramahi I, Ukani L, Perez AM, Fernandez-Funez P, Rincon-Limas D, Botas J: Comparative analysis of genetic modifiers in Drosophila points to common and distinct mechanisms of pathogenesis among polyglutamine diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17 (3): 376-390.

Heinzel T, Lavinsky RM, Mullen TM, Soderstrom M, Laherty CD, Torchia J, Yang WM, Brard G, Ngo SD, Davie JR, et al: A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997, 387 (6628): 43-48. 10.1038/387043a0.

Alland L, Muhle R, Hou H, Potes J, Chin L, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho RA: Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997, 387 (6628): 49-55. 10.1038/387049a0.

Bates EA, Victor M, Jones AK, Shi Y, Hart AC: Differential contributions of Caenorhabditis elegans histone deacetylases to huntingtin polyglutamine toxicity. J Neurosci. 2006, 26 (10): 2830-2838. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3344-05.2006.

Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L: Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001, 410 (6825): 227-230. 10.1038/35065638.

Wang Y, Tissenbaum HA: Overlapping and distinct functions for a Caenorhabditis elegans SIR2 and DAF-16/FOXO. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006, 127 (1): 48-56. 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.005.

Mair W, Dillin A: Aging and survival: the genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008, 77: 727-754. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061206.171059.

Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper MD, Hoddinott M, Sutphin GL, Leko V, McElwee JJ, et al: Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 2011, 477 (7365): 482-485. 10.1038/nature10296.

Jadiya P, Chatterjee M, Sammi SR, Kaur S, Palit G, Nazir A: Sir-2.1 modulates 'calorie-restriction-mediated' prevention of neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans: Implications for Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011

D'Mello SR: Histone deacetylases as targets for the treatment of human neurodegenerative diseases. Drug News Perspect. 2009, 22 (9): 513-524. 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.9.1437959.

Herranz D, Serrano M: SIRT1: recent lessons from mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010, 10 (12): 819-823. 10.1038/nrc2962.

Dietz KC, Casaccia P: HDAC inhibitors and neurodegeneration: at the edge between protection and damage. Pharmacol Res. 2010, 62 (1): 11-17. 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.01.011.

Yacoubian TA, Slone SR, Harrington AJ, Hamamichi S, Schieltz JM, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Standaert DG: Differential neuroprotective effects of 14-3-3 proteins in models of Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1: e2-10.1038/cddis.2009.4.

Wang Y, Oh SW, Deplancke B, Luo J, Walhout AJ, Tissenbaum HA: C. elegans 14-3-3 proteins regulate life span and interact with SIR-2.1 and DAF-16/FOXO. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006, 127 (9): 741-747. 10.1016/j.mad.2006.05.005.

Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L: C. elegans SIR-2.1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins to activate DAF-16 and extend life span. Cell. 2006, 125 (6): 1165-1177. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036.

Slone SR, Lesort M, Yacoubian TA: 14-3-3theta protects against neurotoxicity in a cellular Parkinson's disease model through inhibition of the apoptotic factor Bax. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6 (7): e21720-10.1371/journal.pone.0021720.

Giorgini F, Guidetti P, Nguyen Q, Bennett SC, Muchowski PJ: A genomic screen in yeast implicates kynurenine 3-monooxygenase as a therapeutic target for Huntington disease. Nature genetics. 2005, 37 (5): 526-531. 10.1038/ng1542.

Zwilling D, Huang SY, Sathyasaikumar KV, Notarangelo FM, Guidetti P, Wu HQ, Lee J, Truong J, Andrews-Zwilling Y, Hsieh EW, et al: Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibition in blood ameliorates neurodegeneration. Cell. 2011, 145 (6): 863-874. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.020.

Campesan S, Green EW, Breda C, Sathyasaikumar KV, Muchowski PJ, Schwarcz R, Kyriacou CP, Giorgini F: The Kynurenine Pathway Modulates Neurodegeneration in a Drosophila Model of Huntington's Disease. Curr Biol. 2011, 21 (11): 961-966. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.028.

Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G: Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011, 146 (5): 682-695. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030.

Winslow AR, Chen CW, Corrochano S, Acevedo-Arozena A, Gordon DE, Peden AA, Lichtenberg M, Menzies FM, Ravikumar B, Imarisio S, et al: alpha-Synuclein impairs macroautophagy: implications for Parkinson's disease. J Cell Biol. 2010, 190 (6): 1023-1037. 10.1083/jcb.201003122.

Winslow AR, Rubinsztein DC: Autophagy in neurodegeneration and development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008, 1782 (12): 723-729.

Wong E, Cuervo AM: Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2010, 13 (7): 805-811. 10.1038/nn.2575.

Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, Tsokos M, Alt FW, Finkel T: A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105 (9): 3374-3379. 10.1073/pnas.0712145105.

Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, Liu K, Xu K, Strathearn KE, Liu F, et al: Alpha-synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science. 2006, 313 (5785): 324-328. 10.1126/science.1129462.

Gitler AD, Chesi A, Geddie ML, Strathearn KE, Hamamichi S, Hill KJ, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Cooper AA, Rochet J-C, et al: [alpha]-Synuclein is part of a diverse and highly conserved interaction network that includes PARK9 and manganese toxicity. Nature genetics. 2009, 41 (3): 308-315. 10.1038/ng.300.

Treusch S, Hamamichi S, Goodman JL, Matlack KE, Chung CY, Baru V, Shulman JM, Parrado A, Bevis BJ, Valastyan JS, et al: Functional Links Between Abeta Toxicity, Endocytic Trafficking, and Alzheimer's Disease Risk Factors in Yeast. Science. 2011, 334 (6060): 1241-1245. 10.1126/science.1213210.

Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, Sims R, Gerrish A, Hamshere ML, Pahwa JS, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Williams A, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (10): 1088-1093. 10.1038/ng.440.

Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, Combarros O, Zelenika D, Bullido MJ, Tavernier B, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (10): 1094-1099. 10.1038/ng.439.

Bilen J, Bonini NM: Genome-wide screen for modifiers of ataxin-3 neurodegeneration in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3 (10): 1950-1964.

Gurvitz A, Langer S, Piskacek M, Hamilton B, Ruis H, Hartig A: Predicting the function and subcellular location of Caenorhabditis elegans proteins similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae beta-oxidation enzymes. Yeast. 2000, 17 (3): 188-200. 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)17:3<188::AID-YEA27>3.0.CO;2-E.

Hamamichi S, Rivas RN, Knight AL, Cao S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA: Hypothesis-based RNAi screening identifies neuroprotective genes in a Parkinson's disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105 (2): 728-733. 10.1073/pnas.0711018105.

Ferdinandusse S, Denis S, Hogenhout EM, Koster J, van Roermund CW, L IJ, Moser AB, Wanders RJ, Waterham HR: Clinical, biochemical, and mutational spectrum of peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2007, 28 (9): 904-912. 10.1002/humu.20535.

Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS: OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003, 13 (9): 2178-2189. 10.1101/gr.1224503.

Kuwahara T, Koyama A, Koyama S, Yoshina S, Ren C-H, Kato T, Mitani S, Iwatsubo T: A systematic RNAi screen reveals involvement of endocytic pathway in neuronal dysfunction in α-synuclein transgenic C. elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17 (19): 2997-3009. 10.1093/hmg/ddn198.

Cohen E, Bieschke J, Perciavalle RM, Kelly JW, Dillin A: Opposing activities protect against age-onset proteotoxicity. Science. 2006, 313 (5793): 1604-1610. 10.1126/science.1124646.

Kraemer BC, Schellenberg GD: SUT-1 enables tau-induced neurotoxicity in C. elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16 (16): 1959-1971. 10.1093/hmg/ddm143.

Guthrie CR, Schellenberg GD, Kraemer BC: SUT-2 potentiates tau-induced neurotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2009, 18 (10): 1825-1838. 10.1093/hmg/ddp099.

Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Suzaki T, Ogura T: Analysis of the two p97/VCP/Cdc48p proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans and their suppression of polyglutamine-induced protein aggregation. J Struct Biol. 2004, 146 (1-2): 242-250. 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.11.017.

Yeger-Lotem E, Riva L, Su LJ, Gitler AD, Cashikar AG, King OD, Auluck PK, Geddie ML, Valastyan JS, Karger DR, et al: Bridging high-throughput genetic and transcriptional data reveals cellular responses to alpha-synuclein toxicity. Nature genetics. 2009, 41 (3): 316-323. 10.1038/ng.337.

Blard O, Feuillette S, Bou J, Chaumette B, Frebourg T, Campion D, Lecourtois M: Cytoskeleton proteins are modulators of mutant tau-induced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16 (5): 555-566. 10.1093/hmg/ddm011.

Kaltenbach LS, Romero E, Becklin RR, Chettier R, Bell R, Phansalkar A, Strand A, Torcassi C, Savage J, Hurlburt A, et al: Huntingtin interacting proteins are genetic modifiers of neurodegeneration. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3 (5): e82-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030082.

Shulman JM, Feany MB: Genetic modifiers of tauopathy in Drosophila. Genetics. 2003, 165 (3): 1233-1242.

Ghosh S, Feany MB: Comparison of pathways controlling toxicity in the eye and brain in Drosophila models of human neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2004, 13 (18): 2011-2018. 10.1093/hmg/ddh214.

Fernandez-Funez P, Nino-Rosales ML, de Gouyon B, She WC, Luchak JM, Martinez P, Turiegano E, Benito J, Capovilla M, Skinner PJ, et al: Identification of genes that modify ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration. Nature. 2000, 408 (6808): 101-106. 10.1038/35040584.

Kazemi-Esfarjani P, Benzer S: Genetic suppression of polyglutamine toxicity in Drosophila. Science. 2000, 287 (5459): 1837-1840. 10.1126/science.287.5459.1837.

Auluck PK, Chan HYE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y, Bonini NM: Chaperone Suppression of α-Synuclein Toxicity in a Drosophila Model for Parkinson's Disease. Science. 2002, 295 (5556): 865-868. 10.1126/science.1067389.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a BBSRC Studentship to XC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

XC carried out bioinformatic analyses and interpretation of the data and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. RDB carried out bioinformatic analyses, interpretation of the data and prepared the final version of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2011_3880_MOESM4_ESM.XLSX

Additional File 4: Complied list of all distinct genetic regulators from studies in all three species with orthologues in C. elegans. (XLSX 41 KB)

12864_2011_3880_MOESM5_ESM.XLSX

Additional File 5: Table listing shared genetic regulators found in more than one study of the three model species. (XLSX 16 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Burgoyne, R.D. Identification of common genetic modifiers of neurodegenerative diseases from an integrative analysis of diverse genetic screens in model organisms. BMC Genomics 13, 71 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-71

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-71