Abstract

Background

Variations in gene allele frequencies can contribute to differences in the prevalence of some common complex diseases among populations. Natural selection modulates the balance in allele frequencies across populations. Population differentiation (FST) can evidence environmental selection pressures. Such genetic information is limited in Puerto Ricans, the second largest Hispanic ethnic group in the US, and a group with high prevalence of chronic disease. We determined allele frequencies and population differentiation for 101 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 30 genes involved in major metabolic and disease-relevant pathways in Puerto Ricans (n = 969, ages 45–75 years) and compared them to similarly aged non-Hispanic whites (NHW) (n = 597).

Results

Minor allele frequency (MAF) distributions for 45.5% of the SNPs assessed in Puerto Ricans were significantly different from those of NHW. Puerto Ricans carried risk alleles in higher frequency and protective alleles in lower frequency than NHW. Patterns of population differentiation showed that Puerto Ricans had SNPs with exceptional FST values in intronic, non-synonymous and promoter regions. NHW had exceptional FST values in intronic and promoter region SNPs only.

Conclusion

These observations may serve to explain and broaden studies on the impact of gene polymorphisms on chronic diseases affecting Puerto Ricans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Close to four million Puerto Ricans live in the United States mainland, representing the second largest Hispanic ethnic group after Mexican-Americans [1]. The few studies on health status or disparities that have focused on Puerto Ricans living on the US mainland consistently show excess chronic health conditions for this population when compared with non-Hispanic whites (NHW) and other Hispanic subgroups [2, 3]. In particular, Puerto Ricans exhibit high prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, depression, and cognitive and functional decline [4–9]; national data points to a 12.6% prevalence of diabetes in Puerto Ricans aged 20 years or older [10], while close to 61% of Puerto Rican adults are overweight or obesity [7], and an estimated 9.3% have depression [11].

The etiology of such conditions is multi-factorial, and most likely, a combination of genetic, social and environmental factors define the health disparities observed in Puerto Ricans. Still, studies on the genetic contribution to such conditions in this population are limited. Generalizing genetic risk to Puerto Ricans based on results obtained from other Hispanic groups is inappropriate due to the unique genetic background of this community, which is quite different from other Hispanic populations studied more often [12–14]. Furthermore, extrapolating results from other broadly researched non-Hispanic populations onto Puerto Ricans could lead to inaccurate conclusions [14].

Several reports have discussed the importance of estimating gene allele frequency in epidemiological and genetic association studies [15–17]. Notably, allele frequencies for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can vary by ethnic group, sometimes drastically [18]. Spielman et al. recently showed that expression of individual genes differed significantly between ethnic populations, and that variation in frequency of specific alleles accounted for some of these differences in gene expression [19]. Such variations in minor allele frequency (MAF), when mapping to or affecting genes pertinent to a given disease, could translate into differences in the prevalence and incidence of disease across ethnic groups [20]. Indeed, several studies have shown differences in allele distribution of SNPs in candidate genes for immune response and lipid metabolism as well as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, [17, 18, 20–23]. Myles et al. suggest that SNPs with a large difference in risk allele frequency between populations are strong candidates to explain the variations in disease prevalence between those populations [24]. These observations strongly suggest that Puerto Ricans may also carry disease-associated alleles at frequencies different from other ethnic groups, and that such differences could play a role in the health disparities documented in this population.

The level of population differentiation shown by diverse ethnic groups is related to the variations in allele frequency for genetic polymorphisms [20]. Natural selection modulates the balance in allele frequencies across populations. Certain environmental conditions can act through selective pressure to alter the frequency of a genetic variant resulting in population-specific allele frequencies. Genomic regions of an excess of ancestral divergence between disease and non-disease groups indicates selection signals [25], which allows identification of genomic regions that contribute the risk of disease. Alternatively, the fixation index (FST) measure quantifies population differentiation and tests for evidence of selection pressures, with higher values of FST indicating local positive adaptation and lower values suggesting negative or neutral selection [26]. Several studies have shown that differentiation can vary by chromosomal region and by function of the SNP. Olshen et al. reported regions in chromosomes 2 and 6 with high local FST values that also differed between ethnic groups [27]. In addition, higher FST estimates have been reported for SNPs in functional or coding regions than in non-functional or non-coding SNPs [26, 28]. Barreiro et al. have shown that non-synonymous and 5'-UTR SNPs present extreme degrees of differentiation and positive selection [29]. It has been proposed that loci showing high FST values, or exceptional variance, should be given high priority for association studies of complex diseases and studies on local adaptation to environmental effects [26, 30]. Positively selected alleles (those with high FST values) in disease-associated SNPs could be responsible for differences between populations in prevalence or progression of disease [24]. Although FST values could denote other forces such as genetic drift, bottleneck or founder effect in the population, it is still a useful measure to identify genomic regions of potential environmental interactions and association with disease. Such measures of genetic diversity within a population of Puerto Ricans have not been reported.

We have estimated the ancestry of the Puerto Rican population as 57.2% European, 27.4% African, and 15.4% Native American [31]. Population admixture could influence allele frequencies and thus disease prevalence. Given the high prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity in this population, the aim of this study was to examine the differences in allele frequencies of 101 disease-associated genetic variants in genes of pathways involving lipid and glucose metabolism and inflammation response, between Puerto Ricans and a non-Hispanic white population, which has a much lower prevalence of such conditions and comprise the major ancestry population for Puerto Ricans. In addition, we aimed to identify patterns of population differentiation for Puerto Ricans in comparison to NHW.

Methods

Study populations

The Puerto Rican sample consisted of unrelated participants of the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a cohort of 1020 Puerto Rican subjects at the time of this analysis, designed to study stress, nutrition, health and aging [32]. Eligible subjects were of Puerto Rican descent, between the ages of 45–75, living in the Boston, MA metropolitan area and able to answer interview questions in either English or Spanish. Subjects self-reported their ethnicity. This study obtained Human Investigation Review Board approval from Tufts Medical Center. Participants provided written informed consent.

The NHW sample was comprised of 1506 participants over 18 years of age participating in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study. Participants were recruited from the ongoing NHLBI Family Heart Study in two genetically homogeneous centers (Minneapolis, MN and Salt Lake City, UT) with predominantly NHW populations. Race was self-reported. The primary aim of the GOLDN study was to characterize the role of genetic and dietary factors on an individual's response to fenofibrate. The detailed design and methodology of the study have been described previously [33]. The study was approved by the Human Studies Committee of Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Minnesota, University of Utah, and Tufts Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. To compare with the Puerto Rican population, only data from 597 subjects ages 45–75 years were selected.

Selection of genes and SNPs

Genes and SNPs were selected by bioinformatics analysis, based on previously reported associations or knowledge of their role in known biological pathways such as lipid and glucose metabolism and inflammation response. Briefly, SNP selection took a balanced approach of incorporating results of published studies, of bioinformatics-based predictions of putative functional consequence of the two alleles, and of linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis to diversely and economically sample different genetic blocks. Putative allele-specific function was assessed according to map position within the gene. SNPs in upstream regions and introns were analyzed for altering transcription factor binding sites. Intronic SNPs could also affect mRNA splicing. Non-synonymous SNPs within coding sequences of exons could alter protein sequence, structure and function while synonymous SNPs could call for codons of a different frequency whose effects can be similar to non-synonymous SNPs. Lastly, 3'-UTR SNPs can alter secondary structure which can affect mRNA stability or interactions with small RNAs (e.g., miRNAs). These approaches are detailed elsewhere [34]. A total of 101 autosomal diallelic SNPs from 30 different genes were genotyped. For each SNP, data for the SNP location on the gene and chromosome, function and accession number were obtained from databases published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information [35]. Available information on reported associations with chronic and metabolic conditions was collected by searching the biomedical literature [35]. Only associations for the individual allele or genotype and for healthy adults in the general population were collected, unless otherwise noted. Associations deemed conflicting were not included unless a meta-analysis was available. A list of all genotyped SNPs, with information on chromosome location, variant name, function, and accession number, is included in Additional file 1.

Genotyping

Buffy coats of nucleated cells were obtained from blood samples and genomic DNA was purified using the QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the vendor's recommended protocol. Genotyping was carried out by the 5'-nuclease assay with allele specific TaqMan probes [36]. TaqMan® SNP genotyping assays, either custom (assays-by-design) or pre-designed (assays-on-demand), were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For each reaction, 10 ng of DNA were diluted and aliquoted into 96-well plates. Rapidplate robotic system was used in adding DNA samples from 96-well plates into 384-well plates. For PCR, the DNA was mixed with Taqman Universal PCR MasterMix, Assay and water using a TECAN robotic system. PCR cycles were (1) 10 min at 95°, (2) 15 seconds at 92° and (3) one minute at 60°; repeating steps 2 and 3 for 50 cycles. Blinded no-template controls and replicates of DNA samples were included in the DNA sample plates and routinely checked by the laboratory technicians. Applied Biosystems 7900 was used for allelic discrimination, and Microsoft® Excel macros were used to create the plate records with allele base codes and for cleaning data including: checking on negative controls to ensure the match of plate record and plate, allele frequency calculation to ensure the match of marker name and assay used, and preparation of data ready for export into database. Microsoft® Access was used for data consolidation to ensure accuracy. Quality control estimated the genotyping error rate as less than 1%. The descriptions for primers, probes, and sequences, as well as ABI assay-on-demand ID, are presented in Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 15.0 or Microsoft® Excel. Allele frequencies were estimated based on genotype frequencies. The Puerto Rican sample was analyzed first and minor alleles were assigned based on this population; thus Puerto Ricans have no minor allele frequency greater than 0.50. To calculate the expected MAF of each SNP under an admixture model in Puerto Ricans, we first estimated allele frequency contribution from the European ancestry (57%) and African ancestry (27%) [31], based on the allele frequencies of 73 SNP available in HapMap for the CEU and YRI population reported. As allele frequencies of Native American are not available in HapMap or other sources, we estimated the contribution from Native American ancestry by subtracting the contribution of the European and African ancestries from the observed allele frequencies. The predicted MAF under an admixed model was equal to the sum of contribution from the three ancestries. Pearson's chi-square statistic was used to test Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) for each SNP and to calculate the differences in genotype and allele distributions between Puerto Rican and NHW populations and between the observed and the predicted MAF in Puerto Ricans under an admixture model. Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon non-parametric tests were used to evaluate statistical differences in MAF and FST means between populations and by SNP function. Frequencies and HWE were corroborated on PowerMarker software [37] and no discrepancies were found with the original results. PowerMarker was used to obtain population-specific and between-population FST values (based on the variance of allele frequencies about the means for the population or between populations) for Puerto Rican and NHW populations; the procedure for such measures was formulated in Weir and Hill [38]. Negative FST values were designated as zero, as they cannot be interpreted biologically [39]. Tests between Puerto Rican and NHW populations were deemed statistically significant at P < 0.0005, after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (101 tests); tests at P < 0.0007 were deemed significant for our Puerto Rican sample and the predicted Puerto Rican MAF under an admixture model.

Results

Genotyping data were available for a total of 969 Puerto Rican subjects and 597 NHW subjects. More than 90% of the available samples were genotyped successfully for all but one SNP (FABP1 m2353 in NHW). The two populations were similar in age (mean ± standard deviation = 57.9 ± 7.3 for Puerto Ricans, 57.6 ± 9.2 for NHW), but differed in the distribution of sex, with Puerto Ricans having more female subjects than NHW (72.0% versus 52.6%, respectively). However, females represented the majority of subjects for each group.

For each SNP, the genotype distribution, minor allele frequency, sample size, and p-value from chi-square test for difference in genotype distribution and allele frequency among the two populations are detailed (Additional file 2). Frequencies did not differ by sex (data not shown). Twelve SNPs in the Puerto Rican group and ten in the NHW group were not in HWE at P < 0.05. After Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests, two SNPs were out of HWE: APOC3 3U386 (rs5128) in Puerto Ricans, and FABP1 m2353 (rs3891700) in both populations. As the genotyping error rate was less than 1%, the lack of HWE could be attributed to chance or to small sample size. None of the SNPs were removed from subsequent analysis.

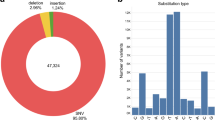

Of the 101 SNPs, 46 (45.5%) showed allele frequency distributions that were significantly different between the two populations at the P < 0.0005 level. Genotype frequencies were significantly different for 41 SNPs. When comparing the observed Puerto Rican MAF versus the predicted MAF under an admixed model, 24 of the 73 (32.9%) SNPs with available data showed significantly different allele frequencies (Additional file 3). Table 1 shows the mean (standard deviation) MAF for Puerto Ricans and NHW by SNP function. There were no statistically significant differences in mean MAF between populations by SNP function. However, for both populations, non-synonymous SNPs had significantly lower MAF than intronic, promoter or synonymous SNPs. Secondary analysis stratifying by chromosome showed that the SNPs in genes mapping to chromosome 8 had significantly lower mean MAF than most chromosomes in both populations, and that for Puerto Ricans, SNPs in chromosome 3 had lower mean MAF than chromosome 2; Puerto Ricans had significantly higher MAF and lower FST for SNPs in chromosome 4 than NHW (data not shown).

To determine if MAF were over- or under-represented on disease-associated SNPs, alleles were categorized as being either protective or risk based on previously reported associations with prevalence or progression of disease. Figure 1 shows the MAF plotted for each population for those alleles classified as either protective or risk, as well as a description of the phenotypes associated with only those SNPs for which MAF is significantly different between populations at the P < 0.0005 level. Puerto Ricans showed significantly lower frequency of the protective minor allele than NHW in four of the nine SNPs examined, including PPARG P12A, GCKR i21532, APOA2 m265 and SCARB1 A350A. These SNPs have been associated with increased high density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and reduced risk or prevalence of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease. Only one protective allele was significantly more frequent in Puerto Ricans, PLIN i5496, which has been associated with lower BMI. The remaining four SNPs did not have significantly different allele distributions between the two populations. For the risk minor alleles, Puerto Ricans showed significantly greater frequency in six of the fourteen examined SNPs. Mainly present in genes of lipid metabolic pathways (APOA5, APOB, APOC3 and LPL), the higher frequency of risk alleles in Puerto Ricans has been associated previously in other populations with unfavorable lipid profile and insulin response, cardiovascular conditions and metabolic syndrome. Only one SNP had significantly lower frequency of the risk allele in Puerto Ricans than NHW, APOB T2515T. The remaining seven SNPs did not have significantly different MAF between populations. Analysis of the 78 SNPs alleles with no conclusive evidence of risk or protection to disease, did not present any differential pattern in MAF distribution between the two populations (data not shown).

Differences in protective (upper panel) or risk (lower panel) minor allele frequency in Puerto Rican versus non-Hispanic whites, by SNP. Tables describe the associated phenotypes for those SNPs with significantly different MAF between populations. *Significantly different MAF between populations, p < 0.0005 Abbreviations: MAF: minor allele frequency; HDL-C: high density lipoprotein; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; CAD: coronary artery disease; BMI: body mass index; TG: triglycerides; LDL-C: low density lipoprotein; VLDL-C: very low density lipoprotein; TC: total cholesterol; IHD: ischemic heart disease; CHD: coronary heart disease; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin.

Additional file 3 lists the FST values for both populations. The population-specific FST was 0.008 for Puerto Rican and 0.039 for NHW, with a between-population FST of 0.020. The between-population FST suggests that the two populations have little differentiation for the markers tested. Population-specific FST has been suggested as the best indicator of selection over between-population FST [30]; thus, we examined the population-specific FST of each SNP for signals of selection. Table 1 shows the mean (standard deviation) and range for FST for Puerto Ricans and NHW by SNP function. There were no statistical differences in FST between populations or by SNP function.

Weir et al. have suggested that when the range of the population-specific value exceeds three standard deviations from the mean, such values can be regarded as exceptionally large and may indicate regions under selection [30]. To identify such exceptional values, Figure 2 shows the FST range (filled circles) for Puerto Ricans (a) and NHW (b) by SNP function, with open squares representing mean FST and bars indicating three standard deviations from the mean for each SNP function category. Exceptionally high values in Puerto Ricans were observed in SNPs located in intronic, non-synonymous and promoter regions, while for NHW they were observed in intronic and promoter SNPs. When stratifying by chromosome during secondary analysis, exceptional FST values were positioned in chromosome 11 for Puerto Ricans, while NHW did not show any exceptional values (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study showed that a group of older adult Puerto Ricans living in the United States had significantly different allele frequency distribution in 101 single nucleotide polymorphisms than similarly aged NHW. Moreover, Puerto Ricans had lower frequency of protective alleles and greater prevalence of risk alleles for SNPs associated with several chronic diseases. Although population differentiation values (FST) did not differ between the two populations, the patterns of FST differed by SNP function in the populations. Puerto Ricans showed exceptional FST values in intronic, non-synonymous and promoter SNPs, while NHW had exceptional values in intronic and promoter SNPs only. These exceptional FST values suggest that selection may be present in genes harboring those SNPs [30].

The differences in allele frequency and population differentiation between the two studied populations may seem surprising as Puerto Ricans comprise an admixed population with European, African and Native American (Taíno) heritage [31]. The value of 45.5% of SNPs showing difference in MAF between the two populations reported here is higher than such differences reported in other populations possibly more distant than Puerto Ricans and NHW. Bamshad et al. found that 41% of SNPs differed significantly between African Americans and European Americans [40]. Moreover, Burchard et al. reported that studies examining the allele frequency distribution among racial groups had found differences of 15% to 20% between groups [41]. Those authors argue that differences in frequency among ethnic groups are typically not as large as those we observed. It is possible that the origins of the white component of the two populations studied here contribute to some of the observed allele frequency differences. The NHW population shares ancestry primarily with individuals from northern and western Europe, while the Puerto Rican population shares ancestry primarily with peoples of the Iberian Peninsula. To determine the contribution of ancestral populations, we calculated the predicted MAF for Puerto Ricans under an admixture model. Close to a third of the SNPs with available data on predicted MAF showed significantly different allele frequencies from our Puerto Rican sample, suggesting that for those loci, the frequencies cannot be explained by admixture alone. However, for the majority of the analyzed SNPs showing similar observed and expected MAF, each ancestral population may be contributing unequal allele frequencies, supporting our conclusion on the large difference between our Puerto Rican sample and the NHW population. The observation that the MAF in Puerto Ricans tended to be lower for protective alleles and higher for risk alleles in disease-associated SNPs is notable. This could be an important factor in the disparities in chronic diseases observed in Puerto Ricans.

Within genomic regions, other groups have found higher MAF in non-coding regions than in coding regions, reflecting the deleterious effect of mutations in coding regions, with promoter regions having the highest MAF [17]. Our observations agree with these previous results, where non-synonymous SNPs have lower mean MAF than SNPs with other functions. We obtained very low FST values for both populations, suggesting very little population differentiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of population differentiation for Puerto Ricans. FST estimates for other racial groups have been reported in a wide range from 0.009 in Ashkenazi Jews and HapMap European populations [27] to 0.11 for SNPs across four HapMap populations [29]. The variations are most likely due to differences in sample size and tested markers.

When assessing exceptional FST values by functional categories of the SNP, our study shows that Puerto Ricans had exceptional FST values in intronic, non-synonymous and promoter SNPs. Analysis of data from NHW exhibited a preponderance of exceptional FST values in SNPs mapping to intronic and promoter regions. In secondary analysis, Puerto Ricans showed a prevalence of exceptional FST SNPs mapping to chromosome 11. Interestingly, chromosome 11 includes four clustered apolipoprotein genes (APOA1, APOA4, APOA5 and APOC3), for which several gene-environment interactions have been reported. In a study with a Puerto Rican sample, Tang et al. showed an excess of Native American ancestry in chromosome 11, which also harbors an olfactory gene cluster that is a target of ongoing positive selection [25]. Kullo and Ding showed high FST values for SNPs in genes of the blood circulation and gas exchange pathways as well as the lipoprotein metabolism pathway in African versus NHW or Asian populations [26]. These observations agree with the prospect that SNPs with high or exceptional FST values should be considered priority candidates for studies on association with complex diseases and local adaptation to environmental influences. Future studies in these populations should focus on intronic, promoter and non-synonymous SNPs for Puerto Ricans, and promoter and intronic SNPs for NHW.

There are limitations to this study. First, the tested SNPs were not randomly selected and thus the frequencies and FST measures may not represent actual distributions, as selective pressures may cause over- or under-representation in disease-associated genes. However, it has been shown that disease-associated SNPs do not show greater population differentiation than SNPs chosen at random [42]. Here, a limited number of tested markers yielded results that could be due to a particular selection. Additionally, statistical power might be limited when stratifying by SNP function (or by chromosome in secondary analysis). Nonetheless, other studies have reported similar measures using fewer SNPs [23, 24]. Furthermore, FST values can also indicate genetic drift and bottleneck effect of the populations. Conclusions about selection based on single marker FST values should be interpreted with caution [24]. Still, the FST estimates provide a practical portrayal of the adaptation processes of Puerto Ricans and surely merit further research. Alternatively, genome-wide genotyping using microarrays will allow detection of selection signal at a genome scale based on an excess of ancestral divergence between disease and non-disease groups [25]. It will also be useful to increase the list of tested markers and of biological pathways, as well as to expand into other genetic measures such as linkage disequilibrium in this Puerto Rican cohort. Finally, we defined risk (or protective) allele based on studies on other, often non-Hispanic, populations assuming these alleles would exert the same impact in Puerto Ricans. The amount of risk or protection conferred by a given allele or the extent of change in a biomarker of disease status may be different in Puerto Ricans, and further association studies should be done to corroborate this.

Alternatively, our study has several strengths. First, noting that there are fluctuations in allele and genotype frequencies in control populations by age and sex [43], we sought to compare the two populations using data from individuals within the same age range. We did not observe any differences by sex. Second, our study has a fairly large sample size. Taioli et al. showed that the deviation of the estimate of allele frequency calculation from the true frequency decreases with increasing sample size, with sample sizes above 500 having almost no deviation [15]. The same principle applies to FST estimates. Third, Akey et al. demonstrated that the average FST values could be affected by genotyping error rates as low as 2–5% [39], but our methods, validated repeatedly, produce less than a 1% genotyping error rate, greatly decreasing the impact of such errors in the FST estimates.

The results of this study have implications in the generation of new hypotheses and selection of candidate genes for association studies and gene-environment interaction studies. Allele frequency variations and FST patterns guide the identification of markers that may have been more prone to local adaptation by past environmental influences that contrast sharply with the environmental pressures faced by Puerto Ricans living in Boston, MA at the present time, namely poor nutritional habits [32]. Such markers are more likely to respond to environmental signals in a manner that manifests as an association with disease status or progression. The observed differences in allele frequency and population differentiation for disease-associated SNPs may explain the disparities in disease prevalence observed in Puerto Ricans. For example, it has been shown that carriers of the variant allele of the Pro12Ala polymorphism in the PPARG gene have a beneficial effect on the measures of glucose metabolism with higher fish intake [44]. Taínos (the Amerindian heritage of modern Puerto Ricans) consumed a diet based on fish, tropical fruits and vegetables, and some small animals [45]. Today, major contributors to the Puerto Rican diet are rice, starchy roots, milk, fried meat products, and processed, Westernized foods, with little consumption of fish [46, 47]. Interestingly, Puerto Ricans from our cohort had significantly higher frequency of this minor allele than NHW; yet the beneficial effect may have been lost with the low consumption of fish in this population today. This warrants assessment of the contribution of this, and other, polymorphisms to the high prevalence of diabetes in Puerto Ricans [4, 48].

Clearly, the goal is to assess genetic and/or environmental contribution to disease to help solve these disparities with targeted interventions and not to create any bias against the populations under study based on genetic profile. Several examples of such ethnicity-based prospective interventions and drug therapies have been reported, such as the population-specific drug-metabolizing capabilities due to various polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes [49]. Finally, this study does not define Puerto Ricans on a genetic level, as they are already a well-defined ethnic group with distinct cultural and social norms and environmental influences, even while sharing some characteristics with other Hispanic subgroups. Further studies on genetic and environmental determinants of disease by ethnic or racial groups should recognize the unique genetic and cultural traits of Puerto Ricans.

Conclusion

Puerto Ricans have significantly different genotype and allele frequency distributions than those of NHW for SNPs in lipid and glucose metabolism, and inflammation response. Puerto Ricans tend to carry risk minor alleles at higher frequency and protective minor alleles at lower frequency than the NHW population. Additionally, patterns of population differentiation were different between the two populations by SNP function. Characterizing the genetic profile of Puerto Ricans will give a solid foundation to the role of genetic variation in disease in an understudied population, support research of genetic interactions with environmental contributors, and help craft interventions to alleviate health disparities in Puerto Ricans.

References

United States Census Bureau: United States General Demographic Characteristics: 2004 American Community Survey. [http://factfinder.census.gov/]

Zsembik BA, Fennell D: Ethnic variation in health and the determinants of health among Latinos. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (1): 53-63. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.040.

Hajat A, Lucas JB, Kington R: Health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups: data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992–95. Adv Data. 2000, 1-14. 310

Cleghorn GD, Nguyen M, Roberts B, Duran G, Tellez T, Alecon M: Practice-based interventions to improve health care for Latinos with diabetes. Ethn Dis. 2004, 14 (3 Suppl 1): S117-121.

Lin H, Bermudez OI, Falcon LM, Tucker KL: Hypertension among Hispanic elders of a Caribbean origin in Massachusetts. Ethn Dis. 2002, 12 (4): 499-507.

Falcon LM, Tucker KL: Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000, 55 (2): S108-116.

Denney JT, Krueger PM, Rogers RG, Boardman JD: Race/ethnic and sex differentials in body mass among US adults. Ethn Dis. 2004, 14 (3): 389-398.

Bermudez OI, Tucker KL: Total and central obesity among elderly Hispanics and the association with Type 2 diabetes. Obes Res. 2001, 9 (8): 443-451. 10.1038/oby.2001.58.

Tucker KL, Falcon LM, Bianchi LA, Cacho E, Bermudez OI: Self-reported prevalence and health correlates of functional limitation among Massachusetts elderly Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and non-Hispanic white neighborhood comparison group. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000, 55 (2): M90-97.

American Diabetes Association: Total Prevalence of Diabetes &Pre-diabetes. [http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics/prevalence.jsp]

Oquendo MA, Lizardi D, Greenwald S, Weissman MM, Mann JJ: Rates of lifetime suicide attempt and rates of lifetime major depression in different ethnic groups in the United States. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004, 110 (6): 446-451. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00404.x.

Martinez-Cruzado JC, Toro-Labrador G, Viera-Vera J, Rivera-Vega MY, Startek J, Latorre-Esteves M, Roman-Colon A, Rivera-Torres R, Navarro-Millan IY, Gomez-Sanchez E, et al: Reconstructing the population history of Puerto Rico by means of mtDNA phylogeographic analysis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005, 128 (1): 131-155. 10.1002/ajpa.20108.

Gonzalez Burchard E, Borrell LN, Choudhry S, Naqvi M, Tsai HJ, Rodriguez-Santana JR, Chapela R, Rogers SD, Mei R, Rodriguez-Cintron W, et al: Latino populations: a unique opportunity for the study of race, genetics, and social environment in epidemiological research. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95 (12): 2161-2168. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668.

Choudhry S, Coyle NE, Tang H, Salari K, Lind D, Clark SL, Tsai HJ, Naqvi M, Phong A, Ung N, et al: Population stratification confounds genetic association studies among Latinos. Hum Genet. 2006, 118 (5): 652-664. 10.1007/s00439-005-0071-3.

Taioli E, Pedotti P, Garte S: Importance of allele frequency estimates in epidemiological studies. Mutat Res. 2004, 567 (1): 63-70. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.06.001.

Race, Ethnicity, Genetics Working Group: The use of racial, ethnic, and ancestral categories in human genetics research. Am J Hum Genet. 2005, 77: 519-532. 10.1086/491747.

Goddard KA, Hopkins PJ, Hall JM, Witte JS: Linkage disequilibrium and allele-frequency distributions for 114 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in five populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2000, 66 (1): 216-234. 10.1086/302727.

Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA: 'Racial' differences in genetic effects for complex diseases. Nat Genet. 2004, 36 (12): 1312-1318. 10.1038/ng1474.

Spielman RS, Bastone LA, Burdick JT, Morley M, Ewens WJ, Cheung VG: Common genetic variants account for differences in gene expression among ethnic groups. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (2): 226-231. 10.1038/ng1955.

Lan Q, Shen M, Garcia-Rossi D, Chanock S, Zheng T, Berndt SI, Puri V, Li G, He X, Welch R, et al: Genotype frequency and F ST analysis of polymorphisms in immunoregulatory genes in Chinese and Caucasian populations. Immunogenetics. 2007, 59 (11): 839-852. 10.1007/s00251-007-0253-3.

Lanfear DE, Marsh S, Cresci S, Shannon WD, Spertus JA, McLeod HL: Genotypes associated with myocardial infarction risk are more common in African Americans than in European Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 44 (1): 165-167. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.053.

Chandalia M, Grundy SM, Adams-Huet B, Abate N: Ethnic differences in the frequency of ENPP1/PC1 121Q genetic variant in the Dallas Heart Study cohort. J Diabetes Complications. 2007, 21 (3): 143-148. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.11.003.

Pemberton TJ, Mehta NU, Witonsky D, Di Rienzo A, Allayee H, Conti DV, Patel PI: Prevalence of common disease-associated variants in Asian Indians. BMC Genet. 2008, 9: 13-10.1186/1471-2156-9-13.

Myles S, Davison D, Barrett J, Stoneking M, Timpson N: Worldwide population differentiation at disease-associated SNPs. BMC Med Genomics. 2008, 1: 22-10.1186/1755-8794-1-22.

Tang H, Choudhry S, Mei R, Morgan M, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Burchard EG, Risch NJ: Recent genetic selection in the ancestral admixture of Puerto Ricans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81 (3): 626-633. 10.1086/520769.

Kullo IJ, Ding K: Patterns of population differentiation of candidate genes for cardiovascular disease. BMC Genet. 2007, 8: 48-10.1186/1471-2156-8-48.

Olshen AB, Gold B, Lohmueller KE, Struewing JP, Satagopan J, Stefanov SA, Eskin E, Kirchhoff T, Lautenberger JA, Klein RJ, et al: Analysis of genetic variation in Ashkenazi Jews by high density SNP genotyping. BMC Genet. 2008, 9: 14-10.1186/1471-2156-9-14.

Rockman MV, Hahn MW, Soranzo N, Zimprich F, Goldstein DB, Wray GA: Ancient and recent positive selection transformed opioid cis-regulation in humans. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3 (12): e387-10.1371/journal.pbio.0030387.

Barreiro LB, Laval G, Quach H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L: Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (3): 340-345. 10.1038/ng.78.

Weir BS, Cardon LR, Anderson AD, Nielsen DM, Hill WG: Measures of human population structure show heterogeneity among genomic regions. Genome Res. 2005, 15 (11): 1468-1476. 10.1101/gr.4398405.

Lai CQ, Tucker KL, Choudhry S, Parnell LD, Mattei J, Garcia-Bailo B, Beckman K, Burchard EG, Ordovas JM: Population admixture associated with disease prevalence in the Boston Puerto Rican health study. Hum Genet. 2009, 125 (2): 199-209. 10.1007/s00439-008-0612-7.

Tucker KL: Stress and nutrition in relation to excess development of chronic disease in Puerto Rican adults living in the Northeastern USA. J Med Invest. 2005, 52 (Suppl): 252-258. 10.2152/jmi.52.252.

Lai CQ, Arnett DK, Corella D, Straka RJ, Tsai MY, Peacock JM, Adiconis X, Parnell LD, Hixson JE, Province MA, et al: Fenofibrate effect on triglyceride and postprandial response of apolipoprotein A5 variants: the GOLDN study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007, 27 (6): 1417-1425. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.140103.

Lai CQ, Tucker KL, Parnell LD, Adiconis X, Garcia-Bailo B, Griffith J, Meydani M, Ordovas JM: PPARGC1A variation associated with DNA damage, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Diabetes. 2008, 57 (4): 809-816. 10.2337/db07-1238.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Livak KJ: Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5' nuclease assay. Genet Anal. 1999, 14 (5–6): 143-149.

Liu K, Muse SV: PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21 (9): 2128-2129. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti282.

Weir BS, Hill WG: Estimating F-statistics. Annu Rev Genet. 2002, 36: 721-750. 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.050802.093940.

Akey JM, Zhang G, Zhang K, Jin L, Shriver MD: Interrogating a high-density SNP map for signatures of natural selection. Genome Res. 2002, 12 (12): 1805-1814. 10.1101/gr.631202.

Bamshad M, Wooding S, Salisbury BA, Stephens JC: Deconstructing the relationship between genetics and race. Nat Rev Genet. 2004, 5 (8): 598-609. 10.1038/nrg1401.

Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, Mountain JL, Perez-Stable EJ, Sheppard D, Risch N: The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348 (12): 1170-1175. 10.1056/NEJMsb025007.

Lohmueller KE, Mauney MM, Reich D, Braverman JM: Variants associated with common disease are not unusually differentiated in frequency across populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2006, 78 (1): 130-136. 10.1086/499287.

Payami H, Zhu M, Montimurro J, Keefe R, McCulloch CC, Moses L: One step closer to fixing association studies: evidence for age- and gender-specific allele frequency variations and deviations from Hardy-Weinberg expectations in controls. Hum Genet. 2005, 118 (3–4): 322-330. 10.1007/s00439-005-0057-1.

Ylonen SK, Salminen I, Lyssenko V, Virtanen SM, Groop L, Aro A, Saloranta C: The Pro12Ala polymorphism of the PPAR-gamma2 gene affects associations of fish intake and marine n-3 fatty acids with glucose metabolism. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008, 62 (12): 1432-1439. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602882.

Rouse I: The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People who Greeted Columbus. 1992, New Haven: Yale University Press

Lin H, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL: Dietary patterns of Hispanic elders are associated with acculturation and obesity. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (11): 3651-3657.

Tucker KL, Bianchi LA, Maras J, Bermudez OI: Adaptation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998, 148 (5): 507-518.

Tucker KL, Bermudez OI, Castaneda C: Type 2 diabetes is prevalent and poorly controlled among Hispanic elders of Caribbean origin. Am J Public Health. 2000, 90 (8): 1288-1293. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1288.

Belle DJ, Singh H: Genetic factors in drug metabolism. Am Fam Physician. 2008, 77 (11): 1553-1560.

Buzzetti R, Petrone A, Ribaudo MC, Alemanno I, Zavarella S, Mein CA, Maiani F, Tiberti C, Baroni MG, Vecci E, et al: The common PPAR-gamma2 Pro12Ala variant is associated with greater insulin sensitivity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004, 12 (12): 1050-1054. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201283.

Deeb SS, Fajas L, Nemoto M, Pihlajamaki J, Mykkanen L, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Fujimoto W, Auwerx J: A Pro12Ala substitution in PPARgamma2 associated with decreased receptor activity, lower body mass index and improved insulin sensitivity. Nat Genet. 1998, 20 (3): 284-287. 10.1038/3099.

Frederiksen L, Brodbaek K, Fenger M, Jorgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Madsbad S, Urhammer SA: Comment: studies of the Pro12Ala polymorphism of the PPAR-gamma gene in the Danish MONICA cohort: homozygosity of the Ala allele confers a decreased risk of the insulin resistance syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87 (8): 3989-3992. 10.1210/jc.87.8.3989.

Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, Lindgren CM, Vohl MC, Nemesh J, Lane CR, Schaffner SF, Bolk S, Brewer C, et al: The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000, 26 (1): 76-80. 10.1038/79216.

Ludovico O, Pellegrini F, Di Paola R, Minenna A, Mastroianno S, Cardellini M, Marini MA, Andreozzi F, Vaccaro O, Sesti G, et al: Heterogeneous effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2 Ala12 variant on type 2 diabetes risk. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007, 15 (5): 1076-1081. 10.1038/oby.2007.617.

Lohmueller KE, Pearce CL, Pike M, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN: Meta-analysis of genetic association studies supports a contribution of common variants to susceptibility to common disease. Nat Genet. 2003, 33 (2): 177-182. 10.1038/ng1071.

Temelkova-Kurktschiev T, Hanefeld M, Chinetti G, Zawadzki C, Haulon S, Kubaszek A, Koehler C, Leonhardt W, Staels B, Laakso M: Ala12Ala genotype of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2 protects against atherosclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89 (9): 4238-4242. 10.1210/jc.2003-032120.

Sparso T, Andersen G, Nielsen T, Burgdorf KS, Gjesing AP, Nielsen AL, Albrechtsen A, Rasmussen SS, Jorgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, et al: The GCKR rs780094 polymorphism is associated with elevated fasting serum triacylglycerol, reduced fasting and OGTT-related insulinaemia, and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008, 51 (1): 70-75. 10.1007/s00125-007-0865-z.

Xiao J, Zhang F, Wiltshire S, Hung J, Jennens M, Beilby JP, Thompson PL, McQuillan BM, McCaskie PA, Carter KW, et al: The apolipoprotein AII rs5082 variant is associated with reduced risk of coronary artery disease in an Australian male population. Atherosclerosis. 2008, 199 (2): 333-339. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.017.

Delgado-Lista J, Perez-Jimenez F, Tanaka T, Perez-Martinez P, Jimenez-Gomez Y, Marin C, Ruano J, Parnell L, Ordovas JM, Lopez-Miranda J: An apolipoprotein A-II polymorphism (-265T/C, rs5082) regulates postprandial response to a saturated fat overload in healthy men. J Nutr. 2007, 137 (9): 2024-2028.

Roberts CG, Shen H, Mitchell BD, Damcott CM, Shuldiner AR, Rodriguez A: Variants in scavenger receptor class B type I gene are associated with HDL cholesterol levels in younger women. Hum Hered. 2007, 64 (2): 107-113. 10.1159/000101962.

Qi L, Corella D, Sorli JV, Portoles O, Shen H, Coltell O, Godoy D, Greenberg AS, Ordovas JM: Genetic variation at the perilipin (PLIN) locus is associated with obesity-related phenotypes in White women. Clin Genet. 2004, 66 (4): 299-310. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00309.x.

Chien KL, Fang WH, Wen HC, Lin HP, Lin YL, Lin SW, Wu JH, Kao JT: APOA1/C3/A5 haplotype and risk of hypertriglyceridemia in Taiwanese. Clin Chim Acta. 2008, 390 (1–2): 56-62. 10.1016/j.cca.2007.12.014.

Maasz A, Kisfali P, Horvatovich K, Mohas M, Marko L, Csongei V, Farago B, Jaromi L, Magyari L, Safrany E, et al: Apolipoprotein A5 T-1131C variant confers risk for metabolic syndrome. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007, 13 (3): 243-247. 10.1007/BF02893505.

Szalai C, Keszei M, Duba J, Prohaszka Z, Kozma GT, Csaszar A, Balogh S, Almassy Z, Fust G, Czinner A: Polymorphism in the promoter region of the apolipoprotein A5 gene is associated with an increased susceptibility for coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2004, 173 (1): 109-114. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.003.

Wang J, Ban MR, Kennedy BA, Anand S, Yusuf S, Huff MW, Pollex RL, Hegele RA: APOA5 genetic variants are markers for classic hyperlipoproteinemia phenotypes and hypertriglyceridemia. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008, 5 (11): 730-737. 10.1038/ncpcardio1326.

Henneman P, Schaap FG, Havekes LM, Rensen PC, Frants RR, van Tol A, Hattori H, Smelt AH, van Dijk KW: Plasma apoAV levels are markedly elevated in severe hypertriglyceridemia and positively correlated with the APOA5 S19W polymorphism. Atherosclerosis. 2007, 193 (1): 129-134. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.030.

Samuels ME, Forbey KC, Reid JE, Abkevich V, Bulka K, Wardell BR, Bowen BR, Hopkins PN, Hunt SC, Ballinger DG, et al: Identification of a common variant in the lipoprotein lipase gene in a large Utah kindred ascertained for coronary heart disease: the -93G/D9N variant predisposes to low HDL-C/high triglycerides. Clin Genet. 2001, 59 (2): 88-98. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.590205.x.

Hoffer MJ, Bredie SJ, Snieder H, Reymer PW, Demacker PN, Havekes LM, Boomsma DI, Stalenhoef AF, Frants RR, Kastelein JJ: Gender-related association between the -93T-->G/D9N haplotype of the lipoprotein lipase gene and elevated lipid levels in familial combined hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 1998, 138 (1): 91-99. 10.1016/S0021-9150(98)00007-0.

Kastelein JJ, Groenemeyer BE, Hallman DM, Henderson H, Reymer PW, Gagne SE, Jansen H, Seidell JC, Kromhout D, Jukema JW, et al: The Asn9 variant of lipoprotein lipase is associated with the -93G promoter mutation and an increased risk of coronary artery disease. The Regress Study Group. Clin Genet. 1998, 53 (1): 27-33. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1998.531530106.x.

Wittrup HH, Andersen RV, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen GB, Nordestgaard BG: Combined analysis of six lipoprotein lipase genetic variants on triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, and ischemic heart disease: cross-sectional, prospective, and case-control studies from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91 (4): 1438-1445. 10.1210/jc.2005-1725.

Garenc C, Couillard C, Laflamme N, Cadelis F, Gagne C, Couture P, Julien P, Bergeron J: Effect of the APOC3 Sst I SNP on fasting triglyceride levels in men heterozygous for the LPL P207L deficiency. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005, 13 (10): 1159-1165. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201469.

Liu HK, Li XF, Zhang SZ, Ren Y, Yong X, Liu YQ, Wang CT, Chen X, Hu YM, Zhang L: Association of Sst I polymorphism in apolipoprotein C3 gene with hypertriglyceridaemia in coronary atherosclerotic heart disease and type II diabetes mellitus in Chinese population. Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 2005, 32 (1): 11-18.

Russo GT, Meigs JB, Cupples LA, Demissie S, Otvos JD, Wilson PW, Lahoz C, Cucinotta D, Couture P, Mallory T, et al: Association of the Sst-I polymorphism at the APOC3 gene locus with variations in lipid levels, lipoprotein subclass profiles and coronary heart disease risk: the Framingham offspring study. Atherosclerosis. 2001, 158 (1): 173-181. 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00409-9.

Chhabra S, Narang R, Krishnan LR, Vasisht S, Agarwal DP, Srivastava LM, Manchanda SC, Das N: Apolipoprotein C3 SstI polymorphism and triglyceride levels in Asian Indians. BMC Genet. 2002, 3: 9-10.1186/1471-2156-3-9.

Han T, Jiang Z, Suo G, Zhang S: Apolipoprotein B-100 gene Xba I polymorphism and cholesterol gallstone disease. Clin Genet. 2000, 57 (4): 304-308. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.570410.x.

Li S, Lei ZW, Chen Z, Lin D, Ke XS, Zhong YM, Wu SF: [Relationship between apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein B polymorphisms in youths with coronary heart disease]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2003, 20 (3): 241-243.

Bernard S, Charriere S, Charcosset M, Berthezene F, Moulin P, Sassolas A: Relation between XbA1 apolipoprotein B gene polymorphism and cardiovascular risk in a type 2 diabetic cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2004, 175 (1): 177-181. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.03.017.

Hegele RA, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Sun F, Harris SB, Zinman B: Common genomic variation in the APOC3 promoter associated with variation in plasma lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997, 17 (11): 2753-2758.

Martinelli N, Trabetti E, Bassi A, Girelli D, Friso S, Pizzolo F, Sandri M, Malerba G, Pignatti PF, Corrocher R, et al: The -1131 T>C and S19W APOA5 gene polymorphisms are associated with high levels of triglycerides and apolipoprotein C-III, but not with coronary artery disease: an angiographic study. Atherosclerosis. 2007, 191 (2): 409-417. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.009.

Talmud PJ, Hawe E, Martin S, Olivier M, Miller GJ, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA, Humphries SE: Relative contribution of variation within the APOC3/A4/A5 gene cluster in determining plasma triglycerides. Hum Mol Genet. 2002, 11 (24): 3039-3046. 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3039.

Muendlein A, Saely CH, Marte T, Schmid F, Koch L, Rein P, Langer P, Aczel S, Drexel H: Synergistic effects of the apolipoprotein E epsilon3/epsilon2/epsilon4, the cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqIB, and the apolipoprotein C3 -482 C>T polymorphisms on their association with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2008, 199 (1): 179-186. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.030.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, Grant Number P01AG023394 and P01AG023394-S1, by contract 53-K06-5-10 from NIH and 58-1950-9-001 and 58-1950-7-707 from the US Department of Agriculture Research Service, and by NIH Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant U 01 HL72524, Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Triglycerides and HL54776.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JM carried out the conception and design of the study, performed the bioinformatics and statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and prepared the draft of the manuscript. LDP assisted in the conception of the study, carried out bioinformatics analysis, and helped draft the manuscript. CQL and JS were involved in data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the draft of the manuscript. BGB and XA carried out the genotyping and participated in reviewing the draft of the manuscript. DA, SD, KLT and JMO participated in the study design and coordination, data interpretation, and in the revision of the draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12863_2009_703_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Gene and genotyping information for 101 SNPs genotyped in Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic white subjects. Gene variant name, location, function, reference number and the corresponding genotyping primer, probe or assay-on-demand ID for 101 SNPs genotyped in Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic white subjects. (DOC 200 KB)

12863_2009_703_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional file 3: Predicted minor allele frequencies, and measures of population differentiation for Puerto Ricans and non-Hispanic whites. Predicted minor allele frequencies under an admixture model, and measures of population-specific and between-population differentiation for Puerto Ricans and non-Hispanic whites. (DOC 258 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mattei, J., Parnell, L.D., Lai, CQ. et al. Disparities in allele frequencies and population differentiation for 101 disease-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms between Puerto Ricans and non-Hispanic whites. BMC Genet 10, 45 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-10-45

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-10-45