Abstract

Background

Geographic clines within species are often interpreted as evidence of adaptation to varying environmental conditions. However, clines can also result from genetic drift, and these competing hypotheses must therefore be tested empirically. The striped ground cricket, Allonemobius socius, is widely-distributed in the eastern United States, and clines have been documented in both life-history traits and genetic alleles. One clinally-distributed locus, isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh-1), has been shown previously to exhibit significant correlations between allele frequencies and environmental conditions (temperature and rainfall). Further, an empirical study revealed a significant genotype-by-environmental interaction (GxE) between Idh-1 genotype and temperature which affected fitness. Here, we use enzyme kinetics to further explore GxE between Idh-1 genotype and temperature, and test the predictions of kinetic activity expected under drift or selection.

Results

We found significant GxE between temperature and three enzyme kinetic parameters, providing further evidence that the natural distributions of Idh-1 allele frequencies in A. socius are maintained by natural selection. Differences in enzyme kinetic activity across temperatures also mirror many of the geographic patterns observed in allele frequencies.

Conclusion

This study further supports the hypothesis that the natural distribution of Idh-1 alleles in A. socius is driven by natural selection on differential enzymatic performance. This example is one of several which clearly document a functional basis for both the maintenance of common alleles and observed clines in allele frequencies, and provides further evidence for the non-neutrality of some allozyme alleles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Individuals within populations are under selection pressure to adapt to their environment; these adaptations can be morphological, physiological, or behavioral in nature. However, these diverse adaptations all have a molecular basis and the study of molecular adaptation to environmental conditions is an active area of research within evolutionary biology. One biochemical adaptation that lends itself to empirical study is the kinetic performance of different enzyme alleles (allozymes) under a range of environmental conditions, such as temperature. Allozyme alleles arise when a point mutation in the protein-coding sequence leads to an amino acid substitution which alters the charge, weight, and folding of the protein [1]. Amino acid substitutions may also affect the function of the protein, altering optimal ranges for temperature, pH, or substrate concentration. Most amino acid changes will likely be deleterious and quickly eliminated by purifying selection [2, 3]. However, some substitutions may not significantly affect the function of the protein, and are therefore selectively neutral, while others may improve enzyme function and be favored by selection.

Originally, evolutionary biologists and geneticists thought genetic diversity in populations would be quite low due to purifying selection [3], but early studies of protein polymorphism revealed unexpected levels of polymorphism at most loci, in a range of organisms including mice, humans, and fruit flies [1–3]; as a result of the high levels of diversity revealed, allozymes were thought to be neutral [4, 5]. However, others believed that allozymes would be subject to selection, and subsequent studies have supported selection in many cases [e.g., [4, 6]]. Thus, a debate over whether allozymes were neutral or were subject to selection began soon after their discovery, and it has been stated that "few subjects in biology have been more strongly debated than the evolutionary significance of protein polymorphisms" [7].

As enzyme function depends on temperature, pH, substrate concentration, and other environmental factors, some amino acid substitutions will result in an enzyme that functions best under certain conditions, and these may be favored locally by natural selection, depending on environmental factors. In populations inhabiting heterogeneous environments, multiple alleles at one enzyme locus may be maintained by balancing selection [8–10]. Evidence for selection acting upon allozyme loci includes the presence of clines in allozyme allele frequencies [7], correlations between environmental variables and allozyme allele frequencies [11], differences in chemical properties between allozyme alleles [12], and differential performance and/or fitness differences between individuals with different allozyme genotypes [e.g., [5, 6, 8, 13, 14]]. These types of evidence are often combined within a system, and several lines of evidence together provide support for the hypothesis that selection is acting on certain allozyme loci (see below).

Another important evolutionary question which is often overlooked is 'why are common alleles common?'. Such common alleles may be prevalent across a wide environmental landscape for many reasons, including ancestral inertia, recent range expansion, genetic drift, purifying selection, or some combination of these or other processes. While it is not always possible to determine the underlying processes that drive or maintain the existence of common allozyme alleles, experiments testing for differential enzyme performance of alleles across a wide-range of environmental conditions can shed light on the possibility of commonness being maintained by natural selection.

Numerous studies providing strong evidence for both neutrality and selection of allozyme loci are found in the literature, and only a few will be detailed here. Cases of neutrality include widespread surveys of allelic variation in white spruce [15], Peromyscus mice [16], and several others [4, 17]. In contrast, strong evidence for selection has been found for two well-studied loci, phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi; [11, 13]) and alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh; [4, 18]) in a wide range of organisms, and for other loci on a smaller scale [e.g., [7, 8]]. Another allozyme locus, isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh), has been studied less than the well-known examples above, but evidence of natural selection acting on this locus has been found across a range of taxa, including bacteria [19, 20], plants [21, 22], invertebrates [23, 24], and vertebrates [25, 26]. Isocitrate dehydrogenase is a metabolic enzyme in the Krebs cycle, and its activity is therefore one of several key steps in the generation of ATP from glucose [5]. In the striped ground cricket, Allonemobius socius, there is a naturally-occurring cline in Idh-1 allele frequencies, hypothesized to have resulted from natural selection [14]. Here, we further test this hypothesis using enzyme kinetics (see below).

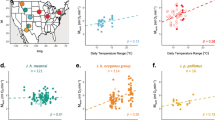

It has been proposed that four criteria are needed to demonstrate selection on a single allozyme locus [27]. First, populations must contain allelic variation at the locus in question. We have previously demonstrated this to be the case for Idh-1 in A. socius, as there is significant geographic variation in the allele frequency distributions of two Idh-1 alleles (1.8 and 2.2), while a third allele (2.0) is found at a frequency of approximately 50% in most locations (Figure 1A). Next, it must be demonstrated that the observed allelic variation is correlated with an ecological variable (or variables), thus linking natural variation in frequencies to a possible selective force. In A. socius, the significant geographic variation in the frequencies of the 1.8 and 2.2 alleles is coupled with significant correlations between allele frequencies and two important environmental variables, temperature (Figure 1B, [14]) and rainfall [14]. Third, there must be phenotypic or fitness consequences to individuals possessing particular alleles in particular environments, providing variation on which selection may act. A previous empirical study of homozygous individuals revealed a significant genotype-by-environment interaction between Idh-1 genotype and temperature on fitness in the direction hypothesized based on the environmental correlations [14], providing experimental evidence supporting temperature-driven selection on the Idh-1 locus in A. socius. The fourth criterion for demonstrating selection on a single enzymatic locus is to show that different allelic variants perform differently under the environmental conditions with which they are correlated (i.e., temperature). Together, these four lines of evidence show that natural variations in allele frequencies are linked to ecologically-relevant differences in enzymatic performance, ultimately leading to differences in organismal fitness on which selection can act [27].

Geographic variation in allele frequencies at the Idh -1 locus in the cricket Allonemobius socius. (A) Allele frequency data from field-collected populations (data from [14]), represented by individual points; lines are least-squares regressions. The 1.8 allele is symbolized by open diamonds and a dashed line, the 2.0 allele by grey squares and a grey line, and the 2.2 allele by black circles and a black line. (B) Relationship between allele frequencies and average summer (June-August) temperature near collection locality.

If selection is acting on a locus of interest, then alleles for that locus which occur at a high frequency across a broad geographic range are expected to outperform less common alleles across a wide range of environmental conditions. Additionally, if clinal variation at a locus of interest is driven by selection, then the common allele in a given environment is expected to outperform less common alleles in that same environment. In contrast, if a locus of interest is evolving under drift, then alleles which occur at a relatively high frequency across a broad geographic range are not expected to perform better than other alleles across a wide range of environmental conditions. Moreover, if clinal variation at a locus is a by-product of drift, then there is no expectation that the common allele in a given environment will perform better than other, less common alleles in that environment. These predictions based on drift also hold for a locus of interest that is evolving neutrally but linked to a locus that is under selection. In both cases, common alleles at the locus of interest in a given environment are not expected to perform better than, or increase fitness relative to, other less common alleles.

Here, we use enzyme kinetics techniques to address the fourth criterion for demonstrating selection acting on a locus for Idh-1 in the model cricket A. socius, and test two specific hypotheses based on the selection vs. drift predictions outlined above: 1) that the 2.0 allele is common across all thermal environments because it performs better than other alleles over a wide range of temperatures, and 2) that the clinal distributions of the 1.8 and 2.2 alleles are due to differences in performance across temperatures, consistent with their geographic distributions. If these two hypotheses are supported, and different alleles perform differently as predicted by their geographic distributions, then there will be strong evidence in support of the fourth criterion required to show selection is acting on the Idh-1 locus in A. socius.

To further explore the hypothesis that selection has shaped allelic distributions of the Idh-1 locus in A. socius, we performed enzyme kinetics assays at a range of ecologically-relevant temperatures (ranging from 18–36°C; see Figure 1B) to explore the molecular basis of the GxE interaction between Idh-1 genotype and temperature. For all 3 kinetic parameters examined (Km, Vmax, and enzyme efficiency), there was a significant GxE between Idh-1 genotype and temperature which affected enzyme performance. Additionally, there were significant differences in performance parameters between alleles at both high and low temperatures. Together, these results provide additional evidence that natural selection underlies the naturally-occurring geographic distribution of Idh-1 alleles in A. socius.

Methods

Study System

Crickets of the genus Allonemobius range from southern Canada to the southern United States, primarily in the East, and are abundant in appropriate habitat throughout their range. Due to their large distribution, abundance in the field, and ease of laboratory maintenance, members of the A. socius complex have been used as a model system for several aspects of evolutionary biology, including studies of speciation and hybrid zone dynamics [28–30], Wolbachia [31, 32], life-history evolution [14, 33–36], and morphological variation [33, 37–39]. Additionally, given their naturally widespread distribution, the A. socius complex is an ideal model system for studying geographic variation in life-history traits and genetic diversity. Within the A. socius complex, clines have been found in ovipositor length [37], diapause occurrence [33, 34, 40], allozyme alleles [14, 28, 30], and nuclear and mitochondrial markers [31].

Members of the A. socius complex are morphologically cryptic, and species were originally discovered and described using allozymes [28, 41, 42]; therefore, much data about the geographic distribution of allozyme alleles are readily available. One locus in particular, isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh-1), is strongly clinal within A. socius, with the 1.8 allele being common in the north and east and the 2.2 allele being common to the south and west (Figure 1A; [14]).

The geographic distributions of these alleles are also correlated with two important environmental variables, temperature (Figure 1B) and rainfall, with 1.8 at highest frequency in cooler, drier locations while 2.2 is associated with hotter, wetter locations [14]. A third allele, 2.0, is found at intermediate frequencies in most locations (~50%; Figure 1A) and not significantly distributed in relation to geography or climate [14]. In a previous study, we found a significant interaction between Idh-1 genotype and temperature on fitness, such that individuals homozygous for the 1.8 allele laid more eggs at a cool temperature relative to the two faster alleles, and individuals homozygous for the two faster alleles laid more eggs at a warm temperature than 1.8 individuals [14]. However, the molecular basis for this GxE was not examined. Here we use enzyme kinetics to assay differences in performance between these 3 alleles across a range of ecologically-relevant temperatures. Temperatures chosen ranged from 18–36°C, and were chosen to reflect temperatures experienced by populations in the field across the species' range (see Figure 1B).

Kinetic Parameters and Calculations

The initial velocity of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction depends on the initial substrate concentration; this relationship is typically hyperbolic, with a linear increase at lower concentrations until the reaction approaches saturation, at which point further increases in substrate will not increase reaction velocity (see Figure 2A). Two important parameters are typically calculated using kinetic assay data: Vmax, the initial reaction velocity at saturated substrate concentration, and the Michaelis constant, Km, which is a measure of the affinity of the enzyme for the substrate and the rate at which the substrate is converted to product [43]. These parameters are obtained through a double-reciprocal plot of velocity against substrate concentration for the linear portion of the original curve (see Figure 2B). First, least-squares regression is performed on the double-reciprocal data and the slope and y-intercept calculated. Vmax is then calculated from the regression equation, using the formula: Vmax = 1/y-intercept [43]. Next, Km is obtained from the equation: Km = Vmax *slope [43].

Example enzyme kinetics data. Experimental Idh-1 kinetic data using homogenates from 1 cricket (2 legs; solid diamonds) and 2 crickets (4 legs; open squares). (A) Initial reaction velocity as a function of substrate concentration, showing the expected hyperbolic relationship. Reaction velocity increases linearly until approaching the saturation point. (B) Lineweaver-Burk plot, the double-reciprocal method for calculating Km, the Michaelis constant, and Vmax, the maximum reaction velocity, from kinetic assay data.

Because the y-intercept changes with enzyme concentration (Figure 2B), Km and Vmax are also influenced by the initial enzyme concentration, such that the values of both parameters increase when enzyme concentration increases (Table 1). However, the slope of the least-squares line is not dependent on the initial enzyme concentration (Figure 2B, Table 1), and is equal to Km/Vmax, a measure of enzyme efficiency. As Vmax is a measure of reaction velocity, a relatively higher value of Vmax means the reaction can progress faster, and therefore higher values of Vmax indicate better enzymatic performance. Conversely, Km contains a measure of enzyme-substrate affinity, and is the amount of substrate needed to achieve one-half Vmax. Therefore, an enzyme with a lower Km needs less substrate to achieve a given rate than one with a higher Km. Lastly, because enzyme efficiency (as defined above) is calculated from reciprocal plots, a smaller value of this parameter (either due to a lower Km and/or a higher Vmax) means the enzyme is more efficient than a higher value. Here we report all 3 kinetic parameters (efficiency, Km, and Vmax), but note that Km and Vmax may be influenced by variation in amount of enzyme present in each individual. Specifically, differences in these two parameters when comparing two individuals could be due to differences in the relative amounts of enzyme in individuals (see Table 1) or real differences in performance between individuals for these two parameters.

Experimental Methods

Experimental Animals

To further detail the relationship between temperature and enzyme activity in A. socius, we conducted an enzyme kinetics experiment using tissue homogenates derived from laboratory-raised Idh-1 homozygotes. Juvenile crickets were collected in July 2006 from a field population in western North Carolina (35.199°N, 81.371°W), an area known to have all 3 alleles at roughly equal frequencies (see Figure 1 in [14]). Field-collected juveniles were raised to adulthood at 27°C in sex-specific cages to prevent mating. Adults were individually genotyped for malate dehydrogenase (Mdh-1; diagnostic of the A. socius complex relative to other species in the genus) and isocitrate dehydrogenase to screen for individuals homozygous at the Idh-1 locus. Allozyme electrophoresis and staining was performed using standard methods for Allonemobius [28].

Individuals homozygous for each of the 3 alleles (1.8, 2.0, and 2.2) were placed in genotype-specific mating cages and allowed to mate for 2 weeks, producing homozygous offspring. Offspring were raised to adulthood at 27°C and ~10 individuals per genotype were randomly chosen and frozen at -80°C. For these individuals, Idh-1 genotype was confirmed with allozyme electrophoresis on head tissue as above. Enzyme homogenates from 3 individuals of each genotype were generated by homogenizing both rear legs in 25 μl 0.2 M tris-citrate buffer, pH 8.0 [28], centrifuging for 2 minutes at 10,000 × g, and removing the supernatant for use in enzyme kinetics assays.

Kinetics Assays

Enzyme kinetics assays were performed in 96-well microplates using a temperature-controlled microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT), similar to the procedure described by [44]. A pilot study was conducted using a wide range of substrate concentrations and standard Idh staining media optimized for Allonemobius ([28]; 0.2 M tris-citrate buffer, pH 8.0 with 1 mg/ml MgCl2, 0.2 mg/ml NADP, 0.2 mg/ml NBT, and 0.04 mg/ml PMS; all reagents from Sigma-Aldrich) to determine the range of concentrations which produced a linear relationship between initial reaction velocity and substrate concentration (see Figure 2A; [43]). This staining solution produces a purple color as the reaction progresses, and absorbance was read at 595 nm using the microplate reader. Although this assay measures combined activity for Idh-1 and Idh-2, the Idh-2 locus is monomorphic in A. socius (and all species of Allonemobius; [14, 29, 30, 42]); therefore, all differences observed between Idh-1 genotypes should result from variation in performance of Idh-1 alleles. From these preliminary data, four concentrations of isocitric acid were used for further assays (0.077, 0.055, 0.043, and 0.035 mg/ml).

Next, assays were performed on 3 individuals per genotype (i.e., 1.8, 2.0, and 2.2 homozygotes) at 7 ecologically-relevant temperatures (18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, and 36°C; see Figure 1B). For each individual, at each temperature and substrate concentration, a 1 μl aliquot of enzyme homogenate was added to 25 μl of staining media and used in an assay following the protocol outlined above. All samples for each temperature were conducted simultaneously with absorbance readings taken for every 15 sec for 20 minutes (yielding 80 absorbance readings per aliquot).

Using standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics [e.g., [43, 45]] implemented by the program KC3 (Bio-Tek Instruments), initial reaction velocity of the enzymatic conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate was calculated using the linear portion of the curve (approximately 5–15 minutes). For each individual at each assay temperature, the increase in velocity with increasing isocitric acid concentration was plotted and slopes calculated (see Kinetic Parameters and Calculations above; Figure 2B), yielding a measure of enzyme efficiency – i.e., the inverse of the change in the rate of the reaction with increasing substrate concentration. Km, and Vmax were also calculated from the assay data using standard methods as described above.

Statistical Analyses

Kinetic data were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Idh-1 genotype as a between-subjects factor and assay temperature and the interaction of temperature and Idh-1 genotype as within-subjects factors. Enzymatic efficiency, Km, and Vmax were analyzed using separate ANOVA's. Post-hoc ANOVA's were then used to test for significant differences between alleles at each temperature and groupings assigned using Ryan-Einot-Gabriel-Welsch (REGWQ) multiple-range tests [46]. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Learning Edition 4.1 [46]. Statistics were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

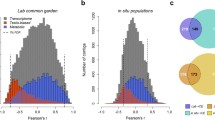

There was a significant interaction between Idh-1 genotype and assay temperature that affected enzyme efficiency, measured as the increase in velocity with increased substrate concentration (Table 2). Because of the inverse relationships plotted by this method, a lower value indicates greater efficiency. Enzyme efficiency was significantly different between alleles at the two lowest temperatures tested (18 and 21°C; Figure 3A), while there was no difference at the higher temperatures tested (24–36°C; Figure 3A). At 18°C, 2.0 individuals outperformed 1.8 and 2.2 individuals, which were not significantly different from each other, while at 21°C, 2.0 and 2.2 individuals were not significantly different and more efficient than 1.8 individuals (Figure 3A).

Kinetic performance across a temperature gradient of 3 Idh -1 alleles in the cricket Allonemobius socius. Enzyme efficiency (A) was measured as the increase in reaction velocity with increasing substrate concentration (see Methods). Km (B) and Vmax (C) were calculated using standard Michaelis-Menten methods. Means ± SE are given (n = 3 individuals per genotype). Individual ANOVA's were used to test for differences between genotypes at each temperature and significant differences indicated (*P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01).

There was also a significant GxE between Idh-1 genotype and assay temperature for Km, the Michaelis constant (Table 3). Km is a measure of the binding affinity between the enzyme and the substrate, and a lower value of Km indicates a higher affinity. There were significant differences in Km between alleles at 3 temperatures (the two lowest temperatures, 18 and 21°C, and the highest temperature, 36°C; Figure 3B). Similar to the results for efficiency (see above), at 18°C, 2.0 individuals had lower Km than 1.8 and 2.2 individuals, which were not different from each other, while at 21°C, 2.0 and 2.2 individuals were not significantly different from each other and had lower Km than 1.8 individuals (Figure 3B). At 36°C, individuals of all three alleles were significantly different from each other, with 2.0 having the lowest Km, followed 1.8 and 2.2 (Figure 3B).

Lastly, the maximum reaction velocity, Vmax, was affected by a significant GxE between Idh-1 genotype and assay temperature (Table 4). At 36°C, 2.2 had a significantly higher Vmax than 1.8 and 2.0, which were not significantly different (Figure 3C). These data indicate that the 2.2 allele encodes an enzyme with the highest velocity but also the highest Km at 36°C, an expected tradeoff between velocity and affinity [5].

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the effect of temperature on enzyme performance can affect many aspects of organismal fitness, including growth rate and size at maturity [47]. Thus, based on previous geographic and empirical data for A. socius, we hypothesized that the observed distributions of Idh-1 alleles, including the high frequency of the 2.0 allele and the cline in the frequency of the 2.2 allele, had resulted from natural selection on differential enzymatic performance across thermal environments. By conducting kinetics assays, we found a significant GxE between Idh-1 genotype and temperature on 3 measures of enzyme kinetic performance in A. socius. Additionally, we found significant differences in performance among alleles at the two lowest and one highest temperatures.

Specifically, at 18°C, 2.0 was more efficient because of higher substrate affinity (lower Km) of the Idh enzyme than the 1.8 and 2.2 alleles. At 21°C, the 2.0 and 2.2 alleles both had higher substrate affinities that that of 1.8 for those two parameters; there was no significant difference among alleles in Vmax at low temperatures. At 36°C, there was no significant difference in overall efficiency between alleles. However, Km and Vmax were significantly higher for the 2.2 allele. Km and Vmax for 2.0 were lower than the other alleles at this temperature, while the 1.8 allele had intermediate values for Km and Vmax when compared to the other two. Overall, we found that Km and Vmax varied at critical temperatures for all 3 alleles, in contrast to the results of Johns and Somero [48], who found that a cold-adapted allele of lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh-4) had a higher Km than warm-adapted alleles across all assay temperatures in Pacific damselfishes.

The kinetics results, in general, are consistent with hypothesized results based on the naturally-occurring distribution of Idh-1 allele frequencies and previous fitness data [14]. Specifically, the 2.0 allele was the most efficient allele at lower temperatures (≤ 27°C) and equivalent in efficiency to the other two alleles at higher temperatures (> 27°C; Figure 3A); these data indicate that the 2.0 allele performs well across the widest range of temperatures, and it is therefore not unexpected that it occurs at approximately 50% frequency in all populations in the eastern United States (Figure 1A; [14]). Conversely, the 2.2 allele had the highest maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) at higher temperatures (≥ 27°C); this allele occurs at approximately equal frequency with the 2.0 allele at lower latitudes, but is not as common to the north (Figure 1A). However, it is somewhat surprising that the 1.8 allele did not perform better at lower temperatures (18 and 21°C), given the earlier fitness data and its geographic distribution (Figure 1; [14]). At the lowest assay temperature (18°C), the 1.8 allele was equivalent to the 2.2 allele in both efficiency and substrate affinity, while the Vmax of all 3 alleles were not significantly different. Thus, we hypothesize that the increased frequency of the 1.8 allele in northern latitudes may be more reflective of processes such as genetic drift, rather than a strict by-product of natural selection. In all, our findings support the hypotheses that 1) the 2.0 allele is common across all thermal environments due to superior performance, for at least some kinetic parameters, relative to the other two alleles at many different temperatures, and 2) the clinal distribution of the 2.2 allele is driven by selection on thermal performance. Combining these data with an earlier study on geographic variation, environmental correlates, and fitness data [14], Idh-1 in A. socius now meets the criteria described by Mitton [27] and others (e.g, [5–8, 11–13]) for demonstrating selection on a single enzyme locus.

In general, enzymatic performance depends on temperature and typically decreases at high temperatures due to degradation and inactivation of enzyme molecules [5, 49–52]. Interestingly, we did not observe a decrease in performance, even in our highest temperature assays (Figure 3). Therefore, the temperature range over which we conducted our assays appears not to have exceeded the thermostability threshold of the isocitrate dehydrogenase enzyme over the time period of the assay, which is not surprising given that temperatures were chosen to reflect the natural conditions experienced by field populations.

At extreme reaction temperatures (cold or hot), researchers typically observe a tradeoff between Km and Vmax. Although an enzyme may tightly bind a substrate, the rate at which the substrate is converted to product may be lower [5, 13, 53–56]. Our data appear to show this tradeoff at our highest assay temperature (36°C), as the 2.2 allele has both the highest Km and Vmax, while 2.0 has the lowest (Figure 3). These data may be influenced by overall differences in amounts of Idh enzyme produced by individuals of different genotypes. However, if differences in performance of alleles at 36°C were due to differences in Idh concentrations among the samples, we would expect alleles to show similar patterns of performance for these two parameters across all temperatures, not just 36°C. Overall, we found that at low temperatures all three alleles have a similar Vmax but significant differences in efficiency and Km, while at high temperatures all three alleles have the same efficiency but significant differences in Km and Vmax (see Figure 3). These findings point to a clear performance tradeoff, in that a single allele cannot perform optimally for all measures of kinetic performance across all temperatures.

When one genotype produces different phenotypes over a range of environmental conditions, the relationship between the phenotype produced and the environment is known as a reaction norm [57]. Similarly, a genotype-by-environment interaction (GxE) occurs when different genotypes produce different reaction norms across the same environmental conditions. Reaction norms and GxE interactions are thought to be adaptive for species living in temporally-variable environments or with wide geographic ranges, as populations may experience different environmental conditions across the species' range or during the year. Such environmental variation can lead to balancing selection on alternative alleles and/or the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Given GxE and spatially- or temporally-variable environments across a species' range, balancing selection is predicted to maintain genetic diversity in natural populations [5, 9, 10, 58]. It appears that all 3 alleles are being maintained in A. socius, possibly due to differences in GxE across temperatures.

There are a few alternative explanations for the allele-frequency distributions observed in natural populations of this species. For example, it is also possible that Idh-1 is linked to another locus which is under temperature-driven selection, and that the allele frequencies observed in nature reflect this linkage disequilibrium [5, 27]. However, our kinetics assays were designed to specifically measure Idh activity, and we observed significant GxE. Alternatively, there could be other genes in the Krebs cycle or other metabolic pathways which are affected by Idh-1 activity and that selection is acting on the pathway as a whole [5]. To further test the hypothesis that natural selection (and/or genetic drift) is acting specifically on the Idh-1 locus in A. socius, we are currently sequencing the protein-coding region for all alleles from multiple individuals spanning the geographic range of this species.

The link between allozyme allele frequencies, differential thermal performance of alleles, and natural environmental gradients has been shown in several other recent studies. For example, Piccino et al. [58] found significant differences in phosophoglucomutase (Pgm-1) allele frequencies between populations of the polychaete Alvinella pompejana which inhabited either newly-created or older hydrothermal vents. The enzyme allele at highest frequency in populations living near recently-established, warmer vents was both more thermostable and had higher activity at warmer temperatures than the allele found in populations dwelling in older, cooler vents [59]. Similar results have been found for Ldh in species of Pacific damselfish of the genera Chromis [48] and Sphyraena [60] inhabiting different thermal regimes. Similarly, clines in allele frequencies of Pgi-1 in the leaf beetle Chrysomela aeneicollis were linked to enzyme kinetic performance across ecologically-relevant temperatures, providing strong evidence of temperature-driven selection [61]. Together, these and other studies indicate that some allozyme loci are not neutral markers of diversity, but rather that the geographic distributions of alleles can be a consequence of environmental conditions and the differential performance of alleles in those environments. Thus, common alleles may be common due to their enhanced performance relative to other, less-common alleles, while clinal distributions can be attributed to either selection or drift across thermal gradients. The distribution of Idh-1 alleles in A. socius appears to be another example of this phenomenon, as we are now able to link a GxE between genotype and temperature on enzyme kinetic performance to the natural distribution of alleles in this species.

Conclusion

Clines in allele frequencies within a species can be caused by natural selection on allele variants along an environmental gradient or by genetic drift across the species' range. Similarly, common alleles may be common due to superior fitness or to genetic drift. Previously, we hypothesized that natural selection may be maintaining a natural cline in Idh-1 allele frequencies (1.8, 2.0, and 2.2) in the cricket A. socius, due to both correlations between allele frequencies and environmental conditions and fitness differences between homozygotes of the various alleles across temperatures [14]. Using enzyme kinetics to further dissect the GxE between Idh-1 genotype and temperature at the molecular level, we found significant differences in enzymatic performance between alleles across temperatures. These data suggest that 1) natural selection is maintaining the cline in frequency of the 2.2 allele, 2) the 2.0 allele is common across a wide geographic range because it performs well across a broad range of temperatures, and 3) drift may be acting on the 1.8 allele. Together, our data indicate that natural selection is acting on the Idh-1 locus in A. socius. Although these enzymatic performance data point to selection maintaining the high frequencies of the 2.0 and 2.2 alleles in given environments, we still have not assessed the molecular signature of positive or balancing selection on the Idh-1 locus. To fill this gap, we are currently sequencing Idh-1 alleles from populations that span the geographic range of A. socius and will be assessing patterns of synonymous and nonsynonymous changes to identify any allele-specific signatures of molecular evolution.

Abbreviations

- Idh :

-

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- GxE:

-

genotype-by-environment interaction

- Km:

-

the Michaelis constant, a measure of affinity

- Vmax:

-

the maximum reaction velocity at saturating substrate concentration.

References

Hubby JL, Lewontin RC: A molecular approach to the study of genic heterozygosity in natural populations. I. The number of alleles at different loci in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 1966, 54 (2): 577-594.

Harris H: Enzyme polymorphisms in man. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1966, 164 (995): 298-310. 10.1098/rspb.1966.0032.

Lewontin RC, Hubby JL: A molecular approach to the study of genic heterozygosity in natural populations. II. Amount of variation and degree of heterozygosity in natural populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 1966, 54 (2): 595-609.

Kreitman M, Akashi H: Molecular evidence for natural selection. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1995, 26: 403-422. 10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.002155.

Eanes WF: Analysis of selection on enzyme polymorphisms. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1999, 30: 301-326. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.301.

Watt WB: Allozymes in evolutionary genetics: self-imposed burden or extraordinary tool. Genetics. 1994, 136 (1): 11-16.

Powers DA, Lauerman T, Crawford D, Dimichele L: Genetic mechanisms for adapting to a changing environment. Annual Review of Genetics. 1991, 25: 629-659. 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003213.

Hotz H, Semlitsch RD: Differential performance among LDH-B genotypes in Rana lessonae tadpoles. Evolution. 2000, 54 (5): 1750-1759.

Schmidt PS, Bertness MD, Rand DM: Environmental heterogeneity and balancing selection in the acorn barnacle Semibalanus balanoides. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 2000, 267 (1441): 379-384. 10.1098/rspb.2000.1012.

Wheat CW, Watt WB, Pollock DD, Schulte PM: From DNA to fitness differences: sequences and structures of adaptive variants of Colias phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2006, 23 (3): 499-512. 10.1093/molbev/msj062.

Riddoch BJ: The adaptive significance of electrophoretic mobility in phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1993, 50 (1): 1-17. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1993.tb00915.x.

Fields PA: Review: Protein function at thermal extremes: balancing stability and flexibility. Comp Biochem Phys A. 2001, 129 (2–3): 417-431.

Watt WB: Eggs, enzymes, and evolution: natural genetic variants change insect fecundity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992, 89 (22): 10608-10612. 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10608.

Huestis DL, Marshall JL: Is natural selection a plausible explanation for the distribution of Idh-1 alleles in the cricket Allonemobius socius?. Ecological Entomology. 2006, 31 (1): 91-98. 10.1111/j.0307-6946.2006.00764.x.

Jaramillo-Correa JP, Beaulieu J, Bousquet J: Contrasting evolutionary forces driving population structure at expressed sequence tag polymorphisms, allozymes and quantitative traits in white spruce. Molecular Ecology. 2001, 10 (11): 2729-2740. 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01386.x.

Storz JF, Nachman MW: Natural selection on protein polymorphism in the rodent genus Peromyscus: evidence from interlocus contrasts. Evolution. 2003, 57 (11): 2628-2635.

Hoffmann AA, Sgro CM, Lawler SH: Ecological population genetics: the interface between genes and the environment. Annual Review of Genetics. 1995, 29: 349-370. 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002025.

McDonald JH, Kreitman M: Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991, 351 (6328): 652-654. 10.1038/351652a0.

Dean AM, Golding GB: Protein engineering reveals ancient adaptive replacements in isocitrate dehydrogenase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997, 94 (7): 3104-3109. 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3104.

Zhu GP, Golding GB, Dean AM: The selective cause of an ancient adaptation. Science. 2005, 307 (5713): 1279-1282. 10.1126/science.1106974.

Hawkins BJ, Sweet GB, Greer DH, Bergin DO: Genetic variation in the frost hardiness of Podocarpus totara. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 1991, 29 (4): 455-458.

Bergmann F, Gregorius HR: Ecogeographical distribution and thermostability of isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh) alloenzymes in European Silver Fir (Abies alba). Biochem Syst Ecol. 1993, 21 (5): 597-605. 10.1016/0305-1978(93)90059-Z.

da Cunha GL, de Oliveira AK: Citric acid cycle: a mainstream metabolic pathway influencing life span in Drosophila melanogaster?. Experimental Gerontology. 1996, 31 (6): 705-715. 10.1016/S0531-5565(96)00056-3.

Sokolova IM, Portner HO: Temperature effects on key metabolic enzymes in Littorina saxatilis and L. obtusata from different latitudes and shore levels. Marine Biology. 2001, 139 (1): 113-126. 10.1007/s002270100557.

Pemberton JM, Albon SD, Guinness FE, Cluttonbrock TH: Countervailing selection in different fitness components in female red deer. Evolution. 1991, 45 (1): 93-103. 10.2307/2409485.

Vrijenhoek RC, Pfeiler E, Wetherington JD: Balancing selection in a desert stream-dwelling fish, Poeciliopsis monacha. Evolution. 1992, 46 (6): 1642-1657. 10.2307/2410021.

Mitton JB: Selection in Natural Populations. 1997, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Howard DJ, Furth DG: Review of the Allonemobius fasciatus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) complex with the description of two new species separated by electrophoresis, songs, and morphometrics. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1986, 79 (3): 472-481.

Howard DJ, Waring GL: Topographic diversity, zone width, and the strength of reproductive isolation in a zone of overlap and hybridization. Evolution. 1991, 45 (5): 1120-1135. 10.2307/2409720.

Britch SC, Cain ML, Howard DJ: Spatio-temporal dynamics of the Allonemobius fasciatus-A. socius mosaic hybrid zone: a 14-year perspective. Molecular Ecology. 2001, 10 (3): 627-638. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01215.x.

Marshall JL: The Allonemobius-Wolbachia host-endosymbiont system: evidence for rapid speciation and against reproductive isolation driven by cytoplasmic incompatibility. Evolution. 2004, 58 (11): 2409-2425.

Marshall JL: Rapid evolution of spermathecal duct length in the Allonemobius socius complex of crickets: species, population and Wolbachia effects. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2 (1): e720-10.1371/journal.pone.0000720.

Mousseau TA, Roff DA: Adaptation to seasonality in a cricket: patterns of phenotypic and genotypic variation in body size and diapause expression along a cline in season length. Evolution. 1989, 43 (7): 1483-1496. 10.2307/2409463.

Mousseau TA: Geographic variation in maternal-age effects on diapause in a cricket. Evolution. 1991, 45 (4): 1053-1059. 10.2307/2409710.

Olvido AE, Busby S, Mousseau TA: Oviposition and incubation environmental effects on embryonic diapause in a ground cricket. Animal Behaviour. 1998, 55: 331-336. 10.1006/anbe.1997.0624.

Huestis DL, Marshall JL: Interaction between maternal effects and temperature affects diapause occurrence in the cricket Allonemobius socius. Oecologia. 2006, 146 (4): 513-520. 10.1007/s00442-005-0232-z.

Mousseau TA, Roff DA: Genetic and environmental contributions to geographic variation in the ovipositor length of a cricket. Ecology. 1995, 76 (5): 1473-1482. 10.2307/1938149.

Fedorka KM, Mousseau TA: Nuptial gifts and the evolution of male body size. Evolution. 2002, 56 (3): 590-596.

Olvido AE, Elvington ES, Mousseau TA: Relative effects of climate and crowding on wing polymorphism in the southern ground cricket, Allonemobius socius (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). Florida Entomologist. 2003, 86 (2): 158-164. 10.1653/0015-4040(2003)086[0158:REOCAC]2.0.CO;2.

Bradford MJ, Roff DA: Genetic and phenotypic sources of life history variation along a cline in voltinism in the cricket Allonemobius socius. Oecologia. 1995, 103 (3): 319-326. 10.1007/BF00328620.

Howard DJ: Speciation and coexistence in a group of closely-related ground crickets. Ph.D. Dissertation. 1982, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Howard DJ: Electrophoretic survey of eastern North American Allonemobius (Orthoptera: Gryllidae): evolutionary relationships and the discovery of three new species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1983, 76 (6): 1014-1021.

Cornish-Bowden A: Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics. 2004, London: Portland Press, 3

Oppert B, Kramer KJ, McGaughey WH: Rapid microplate assay for substrates and inhibitors of proteinase mixtures. BioTechniques. 1997, 23 (1): 70-72.

Levitzki A, Koshland DE: Negative cooperativity in regulatory enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1969, 62 (4): 1121-1128. 10.1073/pnas.62.4.1121.

SAS Institute: SAS Learning Edition 4.1. 2006, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC

Have van der TM, de Jong G: Adult size in ectotherms: temperature effects on growth and differentiation. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1996, 183 (3): 329-340. 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0224.

Johns GC, Somero GN: Evolutionary convergence in adaptation of proteins to temperature: A4-lactate dehydrogenases of pacific damselfishes (Chromis spp.). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2004, 21 (2): 314-320. 10.1093/molbev/msh021.

Daniel RM, Danson MJ, Eisenthal R: The temperature optima of enzymes: a new perspective on an old phenomenon. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001, 26 (4): 223-225. 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01803-5.

Ma YF, Evans DE, Logue SJ, Langridge P: Mutations of barley β-amylase that improve substrate-binding affinity and thermostability. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2001, 266 (3): 345-352. 10.1007/s004380100566.

Peterson ME, Eisenthal R, Danson MJ, Spence A, Daniel RM: A new intrinsic thermal parameter for enzymes reveals true temperature optima. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004, 279 (20): 20717-20722. 10.1074/jbc.M309143200.

Peterson ME, Daniel RM, Danson MJ, Eisenthal R: The dependence of enzyme activity on temperature: determination and validation of parameters. Biochemical Journal. 2007, 402 (2): 331-337. 10.1042/BJ20061143.

Watt WB: Adaptation at specific loci. I. Natural selection on phosphoglucose isomerase of Colias butterflies: biochemical and population aspects. Genetics. 1977, 87 (1): 177-194.

Watt WB: Adaptation at specific loci. II. Demographic and biochemical elements in the maintenance of the Colias PGI polymorphism. Genetics. 1983, 103 (4): 691-724.

Xu Y, Feller G, Gerday C, Glansdorff N: Metabolic enzymes from psychrophilic bacteria: challenge of adaptation to low temperatures in ornithine carbamoyltransferase from Moritella abyssi. Journal of Bacteriology. 2003, 185 (7): 2161-2168. 10.1128/JB.185.7.2161-2168.2003.

Xu Y, Feller G, Gerday C, Glansdorff N: Moritella cold-active dihydrofolate reductase: are there natural limits to optimization of catalytic efficiency at low temperature?. Journal of Bacteriology. 2003, 185 (18): 5519-5526. 10.1128/JB.185.18.5519-5526.2003.

Schlichting CD, Pigliucci M: Phenotypic Evolution: A Reaction Norm Perspective. 1998, Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates

Karl SA, Avise JC: Balancing selection at allozyme loci in oysters: implications from nuclear RFLP's. Science. 1992, 256 (5053): 100-102. 10.1126/science.1348870.

Piccino P, Viard F, Sarradin PM, Le Bris N, Le Guen D, Jollivet D: Thermal selection of PGM allozymes in newly founded populations of the thermotolerant vent polychaete Alvinella pompejana. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 2004, 271 (1555): 2351-2359. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2852.

Holland LZ, McFall-Ngai M, Somero GN: Evolution of lactate dehydrogenase-A homologs of barracuda fishes (genus Sphyraena) from different thermal environments: differences in kinetic properties and thermal stability are due to amino acid substitutions outside the active site. Biochemistry. 1997, 36 (11): 3207-3215. 10.1021/bi962664k.

Dahlhoff EP, Rank NE: Functional and physiological consequences of genetic variation at phosphoglucose isomerase: heat shock protein expression is related to enzyme genotype in a montane beetle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000, 97 (18): 10056-10061. 10.1073/pnas.160277697.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank KL Montooth and MJ Wade for helpful discussions on data analysis and TE Cruickshank, JD VanDyken, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This research was supported by an EPA STAR GRO fellowship to DLH (GAD MA916584), a Highlands Biological Foundation Thelma Howell Memorial Fellowship to DLH, and funding from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station (contribution # 08-386-J) to JLM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DLH co-conceived of the study, carried out laboratory experiments, co-analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. BO helped develop laboratory protocols, supervised laboratory experiments, and contributed to writing of the manuscript. JLM co-conceived the study, co-analyzed the data, and contributed to writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Huestis, D.L., Oppert, B. & Marshall, J.L. Geographic distributions of Idh-1 alleles in a cricket are linked to differential enzyme kinetic performance across thermal environments. BMC Evol Biol 9, 113 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-113