Abstract

Background

The Drosophila larval head is evolutionarily derived at the genetic and morphological level. In the beetle Tribolium castaneum, development of the larval head more closely resembles the ancestral arthropod condition. Unlike in Drosophila, a knirps homologue (Tc-kni) is required for development of the antennae and mandibles. However, published Tc-kni data are restricted to cuticle phenotypes and Tc-even-skipped and Tc-wingless stainings in knockdown embryos. Hence, it has remained unclear whether the entire antennal and mandibular segments depend on Tc-kni function, and whether the intervening intercalary segment is formed completely. We address these questions with a detailed examination of Tc-kni function.

Results

By examining the expression of marker genes in RNAi embryos, we show that Tc-kni is required only for the formation of the posterior parts of the antennal and mandibular segments (i.e. the parasegmental boundaries). Moreover, we find that the role of Tc-kni is distinct in these segments: Tc-kni is required for the initiation of the antennal parasegment boundary, but only for the maintenance of the mandibular parasegmental boundary. Surprisingly, Tc-kni controls the timing of expression of the Hox gene Tc-labial in the intercalary segment, although this segment does form in the absence of Tc-kni function. Unexpectedly, we find that the pair-rule gene Tc-even-skipped helps set the posterior boundary of Tc-kni expression in the mandible. Using the mutant antennaless, a likely regulatory Null mutation at the Tc-kni locus, we provide evidence that our RNAi studies represent a Null situation.

Conclusions

Tc-kni is required for the initiation of the antennal and the maintenance of the mandibular parasegmental boundaries. Tc-kni is not required for specification of the anterior regions of these segments, nor the intervening intercalary segment, confirming that Tc-kni is not a canonical ‘gap-gene’. Our finding that a gap gene orthologue is regulated by a pair rule gene adds to the view that the segmentation gene hierarchies differ between Tribolium and Drosophila upstream of the pair rule gene level. In Tribolium, as in Drosophila, head and trunk segmentation gene networks cooperate to pattern the mandibular segment, albeit involving Tc-kni as novel component.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The insect head is composed of several segments and a non-segmental anterior region. However, the exact segmental composition of the insect head has long been a matter for debate [1–7]. The posterior gnathocephalon is made up of the mandibular, maxillary and labial segments that each bear a pair of appendages specialized for feeding. The anterior procephalon consists of anterior non-segmental parts and an antennal segment, which is separated from the mandibular segment by an appendage-free segment (the intercalary segment), whose development in insects is significantly delayed, as well as reduced in size.

The genetic mechanisms of head segmentation were first examined in the dipteran fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster[3]. Its gnathal segments are patterned by the trunk segmentation gene cascade, involving maternal, gap, pair-rule and segment polarity genes [3, 8], while the patterning of the procephalic segments follows a different paradigm [3, 9–15]. Whilst segment polarity genes (i.e. en, wg, hh) are involved in establishing these segments, pair-rule genes are not [3, 10–15]. Four Drosophila head gap genes, orthodenticle (otd), empty spiracles (ems), buttonhead (btd) and sloppy paired are expressed in broad overlapping domains in the developing anterior head [9, 16]. Mutation of these genes leads to classic ‘gap phenotypes’ - the loss of all the adjacent segments covered by their domains of expression [9, 17]. However, mis-expression studies have shown that only otd affects segment polarity gene expression when expressed in ectopic domains, and only ems, with the help of btd, appears to confer identity to head segments [18–20]. Indeed, second order regulators have been identified that operate at levels in between the head gap genes and segment polarity genes: i.e. collier and cap ‘n’ collar[11, 12, 21, 22].

Drosophila exhibits an evolutionary derived mode of head development, in which the larval head is greatly reduced and undergoes ‘head involution’ during which head regions are folded into the body cavity [3]. This situation is far from typical for insects and moreover, the reduced and experimentally inaccessible Drosophila larval head has limited the comprehensive identification and analysis of insect head development genes for technical reasons [1].

In recent years the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum has emerged as a powerful genetic insect model system [23] and offers an opportunity to study the genetic and cellular mechanisms underlying the development of a more insect-typical head [1]. As in Drosophila, the Tribolium gnathal segments appear to be patterned using similar mechanisms to those operating in the trunk, including a central role for pair-rule gene homologues [24–30]. In the anterior head, second order regulators and the segment polarity genes might be relatively well conserved between Drosophila and Tribolium[27, 28, 31–35]. However, clear differences have been identified at the level of the head gap genes, and the maternally provided anterior protein gradients that establish their expression domains [1, 36–40]. For example, while the Tribolium homologue of orthodenticle (Tc-otd) apparently plays a broadly conserved role as a gap gene during head segmentation in Tribolium, it appears to be much more involved in axis formation than its Drosophila orthologue [36, 41, 42]. The expression of the Tribolium homologues of empty spiracles and buttonhead (Tc-ems and Tc-btd) is limited to single segment wide domains instead of large overlapping domains in the blastodermal head anlagen. Tc-ems is required to form parts of the antennal segment only and knockdown of Tc-btd does not lead to a head cuticle phenotype at all [36]. This raised the question of what genes might control development of these head regions in Tribolium. Work by Cerny et al.[43] suggests that the answer to this question is, at least in part, the single Tribolium homologue of the Drosophila genes knirps and knirps-related.

The Drosophila genes knirps and knirps-related encode steroid hormone receptor-like transcription factors [44–46]. Ancestrally, the insect knirps family consisted of two genes, eagle and knirps-related, while knirps arose via a recent gene duplication of the knirps-related gene in the higher Diptera [47]. At the blastoderm stage, knirps and knirps-related are expressed in almost identical anterior and posterior domains [45, 48–50]. Drosophila knirps acts as a canonical gap gene during trunk segmentation [51–53]. In contrast, the anterior mandibular expression domain is not required for head segmentation, since segment polarity gene (i.e. engrailed) expression in the head is not affected in embryos that lack both paralogues [49] while a loss of the stomatogastric nervous system is observed [49].

Cerny et al.[43] have shown that Tc-knirps (Tc-kni), the single Tribolium homologue of the Drosophila knirps-family paralogues, is also expressed in anterior and posterior domains during early development [43]. However, the Tc-kni posterior domain is shifted anteriorly relative to its position in Drosophila, and knockdown of Tc-kni does not lead to a canonical gap phenotype in the trunk, but rather minor defects in the posterior abdomen. The anterior expression domain of Tc-kni is largely conserved. In contrast to Drosophila, the anterior domain does play an essential role in head patterning: Knockdown of Tc-kni leads to loss of both antennae and mandibles [43].

Cerny et al.[43] found early loss of Tc-wg expression in the antennal segment in Tc-kni RNAi while the mandibular domain of Tc-wg expression disappeared at a later stage. Further, they showed that Tc-kni is not needed for correct Tc-wg expression in the intercalary segment. Finally, light abnormalities in the maturation and maintenance of the first pair-rule stripe of Tc-eve expression were observed, where the distance between the first segmental Tc-eve stripe (in the mandibular segment) and the ocular Tc-wg expression domain was reduced in Tc-kni RNAi blastoderms [43]. It has remained unclear, however, whether antennal and mandibular segments are deleted completely and whether the intercalary segment is affected.

In this study we examined the effect of knocking down Tc-kni on a comprehensive set of genes that mark sub regions of the antennal, intercalary and/or mandibular segments. We show that Tc-kni is required for correctly specifying only posterior regions of antennal and mandibular head segments (i.e. the parasegmental boundaries). Interestingly, Tc-kni is essential for the initial specification of the antennal parasegmental boundary, while it is required only for the maintenance of the mandibular parasegmental boundary. The intercalary segment does not appear to be affected. Unexpectedly, we find that the trunk pair-rule gene Tc-even-skipped is required to set the posterior boundary of the mandibular Tc-kni expression. Unlike most RNAi studies, we have good evidence that we were investigating a Null situation due to our finding that antennaless, a Tribolium mutant arising from an EMS screen [54], is a likely regulatory Null-mutation of Tc-kni. Taken together, we show that Tc-kni is not a head gap gene, since its mutation does not lead to the complete deletion of several adjacent segments. Further, we provide a model, for how head and trunk patterning mechanisms cooperate to pattern the mandibular segment in Tribolium, and how these interactions differ between Drosophila and Tribolium.

Results and discussion

Early Tc-kniexpression prefigures the appearance of the anterior head anlagen

First, we studied in more detail the dynamics of anterior Tc-kni expression because previous studies had focused on posterior aspects [43]. Zygotic Tc-kni expression in the syncytial blastoderm begins as a broad domain covering most of the anterior half of the blastoderm, only absent from a small region around the anterior pole (Figure 1A). Tc-kni expression then retreats from the anterior pole, but much more so on the dorsal side of the egg, clearing from regions that will later become the extra-embryonic serosa (Figure 1B) [55]. Tc-kni expression is maintained in the anterior/ventral regions that will become head tissue [55] (Figure 1C). These early shifts in expression occur before embryonic and extra-embryonic tissue can be distinguished at the level of nuclear morphology (Figure 1A’-C’ and Cerny et al.[43]). When this distinction becomes apparent (Figure 1D’-F’), the uniform anterior Tc-kni expression domain splits into two anterior lateral domains at the boundary between each head lobe and the abutting extra-embryonic tissue (black arrows), and a more posterior stripe marking the future anterior compartment of the mandibular segment (black arrowheads) (Figure 1D-F). These domains are maintained through subsequent blastoderm (Figure 1G-I) and early germband (Figure 1J, K) stages, before fading (Figure 1L, M) and then disappearing completely during mid-germband elongation stages. Hence, the early uniform domain of Tc-kni expression (Figure 1C) encompasses the entire future anterior head anlagen; i.e. everything anterior to the parasegment 0/1 boundary.

Embryonic expression of Tc-kni and the Tc-kni head cuticle phenotype. A-M: Expression of Tc-kni during blastoderm (A-H’) and early germband stages (I-M). See text for a detailed description. Panels A’-H’ show inverted DAPI images of the embryos in panels A-H respectively. Black arrows in panels D-M mark Tc-kni expression at the anterior border of one or both head lobes. Black arrowheads in panels D-M indicate the stripe of Tc-kni expression marking the anterior compartment of the mandibular segment. White arrowheads in panels E-M mark the posterior domain of Tc-kni expression which first becomes visible within the primitive pit as it forms (E-I) and later resolves into a stripe marking segment A1 (J-M). Anterior is to the left in panels A-H’ and to the top in panels I-M. Panel B shows a dorso-lateral view, panels D, E and G show ventro-lateral views, panel C and F lateral views, and panels H-M are all ventral views. N-O: In contrast to wildtype (N), antennaless mutant first instar larvae (O) lack antennae (black arrows in panel N) and mandibles (black arrowhead in panel N). All lateral and dorsal head bristles are however present.

Antennaless is likely a regulatory mutation at the Tc-knilocus

In most RNAi experiments outside Drosophila, it remains unclear to what extent a genetic Null-situation is phenocopied. We aimed at determining the Null situation by studying a genetic mutant.

Antennaless is a homozygous lethal mutation that was recovered from an EMS mutagenesis screen [54]. The cuticular phenotypes of antennaless mutant larvae are highly reminiscent of Tc-kni RNAi phenotypes (Tc-kniRNAi) [43]. Larvae of the antennaless mutant lack antennae and mandibles, and occasionally also display minor abdominal defects, very similar to those previously reported for weak Tc-kniRNAi larvae (Figure 1N, O and Cerny et al.[43]). In order to check for defects in dorsal and lateral head tissues which are derived from pre-antennal and intercalary regions, respectively [32, 36, 56], we scored both sides of 20 antennaless larval cuticles for the head bristle pattern. All bristles were present, albeit shifted somewhat compared to the wildtype condition in these regions (Figure 1N, O). This is consistent with pre-antennal regions and much of the intercalary segment not being affected in the mutant [32, 43].

The development of both mandibles and antennae was more severely affected at a higher temperature in antennaless mutants. A larval cuticle was scored as an antennaless mutant if either the mandibles or antennae, or both, were reduced or absent. Most of the antennaless mutant larvae (67%, n = 43) lacked both the antennae and mandibles at 25°C. This increased to 75% (n = 32) at 32°C. In a few cases, rudiments of mandibles were found (5% at 25°C and 6% at 32°C). In other cases, antennae or antennal rudiments were found (28% at 25°C and 19% at 32°C). In contrast, and against the general observation that phenotypes tend to be more penetrant at higher temperatures, the frequency of abdominal defects was found to be higher at 25°C than at 32°C. At 25°C, 90.5% (n = 43) of phenotypic larvae displayed defects within segments A5-A8, compared to only 16% (n = 32) at 32°C. An inverse sensitivity with respect to temperature was also observed for defects in the urogomphi, dorsal outgrowths of the ninth segment. At 25°C this structure was defective in 79% of the phenotypic larvae examined (n = 43), compared to 44% at 32°C (n = 32).

In offspring from nine independent pairs of heterozygous parents, the antennaless cuticle phenotype is found in 25% (n = 364) and 27% (n = 267) of larvae at 25°C and 32°C respectively, levels consistent with a highly penetrant homozygous lethal mutation. A significant proportion of mutant larvae were able to hatch despite their lack of antennae and mandibles; 45% at 25°C (n = 91) compared to only 17% at 32°C (n = 72). The vast majority of these larvae died at the L1 stage. Only very rarely did individuals reach the L2 stage. When corrected for a background reduction in hatching rate associated with this shift in temperature (measured from wildtype larvae), these data reveal a 19% increase in sensitivity to temperature with regards to hatching in the antennaless mutant background.

In our Tc-kni RNAi experiments head defects were also found to be more severe at 32°C compared to 25°C (see Additional file 1, compare panel B to panel A). The severity of head defects decreased over time post-injection as expected for parental RNAi experiments [57] (see Additional file 1, panel C). However, as for antennaless, we found inverse temperature sensitivity with respect to defects in segments A5-A8 following Tc-kniRNAi (see Additional file 1, compare panel E to panel D). The frequency of abdominal defects also increased with time post-injection from about 20% (n = 10) at day eight post-injection, to 37% (n = 35) eleven days post-injection, and to 56% (n = 27) thirty-one days post-injection, before dropping again (For eggs at 25°C; see Additional file 1, panel D). This is not in line with the usual observation that in RNAi experiments phenotypic strength decreases over time and indicates a complex relationship between knockdown and phenotype, which we do not fully understand.

Since the antennaless cuticle defects described above are almost identical to the Tc-kniRNAi phenotypes both in terms of physical phenotype and sensitivity to temperature, we suspected Tc-kni as the gene affected by the mutation. We therefore independently sequenced the three Tc-kni exons from the genomic DNA of two first instar larvae that had been identified as homozygous mutant by their cuticle phenotype. We found that the coding sequence of Tc-kni is not altered in mutant beetles (data not shown).

In order to test the hypothesis that antennaless is a regulatory mutation at the Tc-kni locus, we carried out in situ hybridization on embryos from heterozygous mutant parents with a mix of probes targeting Tc-kni and Tc-caudal as positive control. We failed to detect Tc-kni expression in 15% of the offspring examined (n = 100), whereas Tc-caudal was well stained in the same colour reaction in all cases (see Additional file 2). This is consistent with embryos homozygous for the antennaless allele not expressing Tc-kni at levels detectable via in situ hybridization.

Taken together, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that antennaless is a regulatory mutation of Tc-kni, and as such we now refer to it as Tc-kniatl. However, we cannot rule out that antennaless is a mutation in a gene that acts rather exclusively upstream of, or is a required interaction partner of, Tc-kni. Further studies will be necessary to confirm our hypothesis by identifying the cis-regulatory regions that are affected by the mutation.

The Tc-kni Null phenotype is revealed by both Tc-kniatl and Tc-kniRNAi

The lack of Tc-kni expression in homozygous Tc-kniatl embryos implies that Tc-kni function is strongly reduced in the mutant. However, it remains possible that some residual function remains. In order to test whether Tc-kniatl constitutes a complete Null phenotype for Tc-kni, we performed Tc-kni RNAi in the Tc-kniatl background, assuming that the added effects should not lead to stronger phenotypes if Tc-kniatl is a Null mutant. The frequency of the Tc-kni phenotype in the pooled offspring from 30 independent pairs of Tc-kniatl heterozygous animals was 11% (n = 149) at 25°C and 17% (n = 82) at 32°C. As expected, after injecting the same females with Tc-kni dsRNA, the frequency of the Tc-kni phenotype strongly increased, to 97% (n = 32; 25°C) and 81% (n = 32; 32°C). Crucially, we did not find evidence for an increase in the severity of the cuticle phenotype: i.e. there were no larvae with phenotypes more severe than those seen in Tc-kniatl or Tc-kniRNAi alone. Hence, unlike in most RNAi experiments, we can be rather confident that the most severe RNAi phenotypes we observe fully phenocopy a Null situation. Therefore, we use results from both mutant and RNAi embryos for this work.

Tc-kniis differentially required for specifying antennal, intercalary and mandibular parasegment boundaries

The cuticle phenotypes reported by Cerny et al.[43] raised the question of whether entire segments are deleted in Tc-kni depleted embryos, or only the posterior parts that give rise to the appendages. These depend on parasegmental boundary formation via the segment polarity genes Tc-engrailed (Tc-en), Tc-hedgehog (Tc-hh) and Tc-wingless (Tc-wg) [5, 10, 13, 21, 22, 27–29]. Therefore, we stained Tc-en and Tc-hh in Tc-kniRNAi embryos as markers for the posterior segment compartment. In the case of Tc-en, embryos were co-stained for Tc-Dfd to help distinguish disrupted mandibular Tc-en expression domains (which are located within the Tc-Dfd domain), from intercalary Tc-en expression domains (arising at the anterior median boundary of the Tc-Dfd domain) (Figure 2J-K, N-O, black asterisks).

Expression of Tc-en and Tc-Dfd in wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. The antennal Tc-en stripe (marked by white arrowhead in wildtype panels A, D, G, J, M) is missing in all Tc-kni RNAi embryos. The mandibular Tc-en stripe (marked by black arrow) forms within the Tc-Dfd expression domain, but is broken (panels B, C, E, H, K, L, N) and often missing (panels F, I, O) in Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Tc-en expression in the intercalary segment (black asterisk in panels J-L, N-O; hidden by antenna in panel M) appears at a variable time point in mid-elongation stage embryos at the anterior border of the Tc-Dfd expression domain in both wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Tc-en expression associated with structures at the base of the antenna is evident in late Tc-kni RNAi embryos (red arrows in panels K-O). Head lobes appear reduced in size (panels A’-C’), and the Tc-Dfd domain slightly narrower (panels G-O) in Tc-kni RNAi embryos, consistent with a failure to specify and form posterior antennal and mandibular tissue. Black arrowheads in panels D-O mark the maxillary Tc-en stripe. Ventral views, and anterior towards the top, in all panels.

We find that both Tc-en (Figure 2) and Tc-hh (Figure 3) expression is absent in the antennal segment in Tc-kniRNAi embryos throughout embryogenesis (marked by white arrowhead in wildtype embryos in Figures 2 and 3). Occasionally, Tc-en and Tc-hh expression associated with structures at the base of the antenna remains in later germband embryos, despite the clear failure of the antenna to form (marked by a red arrow in panels K, L, M, N and O in Figure 2 and panels F and H in Figure 3).

Expression of Tc-hh in wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. The antennal Tc-hh stripe (marked by white arrowhead in wildtype panels A, C, E, G) is missing in all Tc-kni RNA embryos (panels B, D, F, H). The mandibular Tc-hh stripe (marked by black arrow in panels A, C, E, G) is broken (panels B, D) and later missing (panels F, H) in Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Tc-hh expression in the intercalary segment (black asterisks in panels E, F) appears at a variable time point in mid-elongation stage embryos in both wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Tc-hh expression associated with structures at the base of the antenna is evident in late Tc-kni RNAi embryos (red arrow in panels F, H). A black arrowhead in all panels marks the maxillary Tc-hh stripe. Ventral views, and anterior towards the top, in all panels.

The mandibular stripe of Tc-en expression is initiated in early Tc-kniRNAi germband embryos, albeit abnormally; the stripe of expression is broken and in extreme cases only patches of expression are seen (compare panels B and C with panel A in Figure 2; mandibular stripe marked by black arrow). In older Tc-kniRNAi germband embryos, Tc-en expression associated with the mandibular segment is often missing completely (compare panels F, I and O, with panels D, G and M respectively in Figure 2), suggesting a failure to properly maintain Tc-en expression in this segment in strong knockdowns of Tc-kni expression. Similarly, Tc-hh expression in the mandibular segment is greatly reduced in young Tc-kniRNAi embryos, but a thin broken stripe is still detected medially in early germbands (compare black arrows in panels B and D to panels A and C respectively in Figure 3). Later, this Tc-hh expression disappears in contrast to wildtype (compare panels F and H to panels E and G respectively in Figure 3). Note that Tc-en mandibular expression appears to be more sensitive to the loss of Tc-kni expression in lateral regions of the germband (Figure 2E, H, K and N).

Tc-en and Tc-wg expression in the intercalary segment appears relatively late and at a quite variable time point during mid germband elongation in wildtype embryos. Whilst we cannot completely rule out minor disruptions of intercalary Tc-en/Tc-hh expression initiation and/or maintenance in Tc-kniRNAi embryos, we do detect wildtype expression of these genes in late elongation (i.e. post 10 Tc-en stripe embryos) and early fully elongated Tc-kniRNAi embryos (black asterisk in panels K, L, N and O in Figure 2 and black asterisk in panel F in Figure 3).

In conclusion, the disruption of Tc-kni function leads to the complete failure to initiate segment polarity gene expression in the antennal segment, failure to properly maintain segment polarity gene expression in the mandibular segment, and most likely has no effect on segment polarity gene expression in the intercalary segment [43].

Molecular markers show that Tc-kniis not a canonical head gap gene

Segment polarity genes mark a posterior portion of each segment. Therefore, we also asked whether the anterior parts of the segments are miss-specified and/or missing in Tc-kniRNAi embryos by analyzing markers for the anterior regions of head segments. Tc-goosecoid (Tc-gsc) expression [56] initially partially overlaps the ocular Tc-wg domain and extends posterior to it (Figure 4A). Later, this domain widens in lateral regions, forming a wedge shape domain that abuts the antennal Tc-wg stripe as it appears (Figure 4C) but later retracts from it (Figure 4E). Thus, Tc-gsc is a marker for posterior ocular and anterior antennal regions in early embryos but later predominantly marks ocular tissue. In early Tc-kniRNAi germband embryos, Tc-gsc expression is down-regulated in posterior-lateral regions of the wedge shaped expression domain (black arrows in Figure 4B, D; compare to Figure 4A, C respectively). In older Tc-kniRNAi embryos, the Tc-gsc expression domain again closely resembles the wedge shape seen in wild-type embryos at these stages (Figure 4F). This indicates that the ocular parasegment boundary and anterior parts of the antennal segment are not greatly affected by loss of Tc-kni, apart from some degree of lateral down-regulation of Tc-gsc in early germ bands.

Expression of Tc-gsc and Tc-lim1 in wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. All embryos are also co-stained for Tc-wg. Tc-gsc expression is reduced in posterior-lateral regions of its normally wedge-shaped ocular/antennal expression domain in early germband Tc-kni RNAi embryos (black arrows in panels B, D; compare to panels A, C respectively). At slightly later germband stages however, clear differences between the Tc-gsc expression domain in Tc-kni RNAi and wildtype embryos are no longer observed (compare panel F to panel E). Tc-lim1 expression is also irregular and reduced in posterior regions of its wedge-shaped ocular/antennal expression domain in early germband Tc-kni RNAi embryos (black arrowheads in panel H; compare to panel G). At slightly older germband stages clear differences in the Tc-lim1 expression domain are no longer observed between Tc-kni RNAi and wildtype embryos (compre panel J to panel I). In later wildtype germband embryos, the Tc-lim1 ocular/antennal domain splits into two stripes (marked by white arrowheads in panel K). This fails to occur in equivalent stage Tc-kni RNAi embryos, and antennal, mandibular and maxillary expression domains are often fused in lateral regions of the germband (red arrowheads in panel L; compare to panel K). Ventral views, and anterior to the top, in all panels.

Tc-lim1 is a similar marker for the posterior of the ocular segment and anterior compartment of the antennal segment [56], albeit shifted slightly posteriorly relative to Tc-gsc. In early embryos, expression is partially overlapping the ocular Tc-wg domain and extending posterior to it (Figure 4G). In elongating germbands, Tc-lim1 expression forms a wedge shaped domain that covers all cells between the ocular and antennal Tc-wg stripes (Figure 4I). In the Tc-kniRNAi background, the posterior boundary of this domain is irregular and the domain is somewhat narrower indicating posterior reduction of the Tc-lim marked tissues (Figure 4H). In wild-type elongating germbands, additional Tc-lim1 segmental expression arises that laterally overlaps the segmental Tc-wg domains in gnathal and thoracic segments (Figure 4K). At these stages, the ocular-antennal domain of Tc-lim1 expression splits into a posterior domain that overlaps the antennal Tc-wg stripe, and an anterior domain positioned between the ocular and the antennal Tc-wg stripes (Figure 4K; white arrowheads). Expression in the ocular-antennal region remains also in Tc-kniRNAi germbands, but the domain is not split as in wildtype (upper red arrowhead in Figure 4L) and appears to be fused with the mandibular domain of lateral Tc-lim1 expression (lower red arrowhead in Figure 4L). In extreme cases this domain is also fused to the maxillary Tc-lim1 expression domain (Figure 4L and discussed below). This confirms that anterior antennal tissue is properly specified while the parasegmental boundaries of the antennal and mandibular segments are not formed correctly.

Tc-empty-spiracles (Tc-ems) is expressed in a segmentally reiterated pattern during Tribolium development [36] in mediolaterally-restricted domains that lie anterior to the Tc-wg stripe in each segment [36]. Tc-ems expression therefore predominantly marks the anterior portion of each segment. In contrast to wild-type expression, the antennal and mandibular Tc-ems segmental domains are fused in Tc-kniRNAi embryos (red arrows in Figure 5B), as seen for Tc-lim1. This is consistent with defects being restricted to the posterior compartment of the antennal segment leading to the fusion of the antennal and mandibular Tc-ems expression domains.

Expression of Tc-ems and Tc-slp-1 in wildtype, Tc-kni RNAi and antennaless embryos. Panels B, D, E, G and H represent documentation of fluorescent FastRed stainings of the respective gene and are therefore shown in grayscale. Tc-ems expression in the antennal (white arrowhead, panels A, B) and mandibular (black arrow, panels A, B) segments is abnormally fused in Tc-kni RNAi embryos (red arrows in panel B; compare to panel A). A black arrowhead marks the maxillary domain of Tc-ems expression in panels A, B. The antennal Tc-slp-1 expression domain (white arrowhead, panels C-H) is often expanded, while the mandibular (black arrow, panels C-H) and maxillary (black arrowhead, panels C-H) Tc-slp-1 expression domains are fused (red arrows in panels D-E, G-H) in Tc-kni RNAi and antennaless embryos. Ventral views, and anterior to the top, in all panels.

Tc-sloppy-paired-1 (Tc-slp-1) is also expressed in a segmentally reiterated pattern in the developing Tribolium head (Figure 5C, F and [25, 32]). Tc-slp-1 expression domains overlap the Tc-wg stripe in each head segment, but also extend further into the anterior compartment, as well as a little across the parasegmental boundary into the posterior compartment [25, 32]. Tc-slp-1 expression therefore predominantly marks a posterior portion of the anterior segment compartment. Tc-slp-1 is expressed in a stripe in the antennal and each gnathal head segment in both Tc-kniRNAi and Tc-kniatl embryos (Figure 5D, E and G, H), as in wild-type embryos (Figure 5C, F). However, the antennal stripe often appears to broaden (white arrowhead in Figure 5D, E, H), and the distance between the mandibular and the maxillary Tc-slp-1 stripes is often decreased, completely fusing in lateral regions (red arrows in Figure 5D, E and G, H). These data indicate that overall the Tc-slp-1 stripes are not dramatically affected by Tc-kni RNAi. However, the decreased distance between the mandibular and maxillary stripes could indicate incorrectly specified tissue in the intervening posterior compartment of the mandibular segment.

A normal complement of bristles and setae in lateral regions of Tc-kniatl larval heads implies the retention of intercalary segment derived cuticle in Tc-kni knockdown embryos (Figure 1 and [32]). Since Tc-labial (Tc-lab) is expressed during embryogenesis throughout the presumptive intercalary segment [58], and is required for its formation [32], we used it as a molecular marker for the presence/absence of the intercalary segment. In Tc-kni RNAi embryos (Figure 6G-L), Tc-lab expression appears prematurely but with similar dynamics as in wildtype (Figure 6A-F). The premature Tc-lab expression domain first appears medially as a pair of dots on either side of the median mesoderm (Figure 6G; compare to wild-type in Figure 6A). Tc-lab expression then extends into more lateral and medial regions. Expression is not entirely wildtype, as it may form an unusual regular stripe without the typical median expansion (compare Figure 6H, L with D, F), or it may be laterally reduced (Figure 6I, J, K). However, in all instances, the stripe was present indicating that the intercalary segment is present albeit its morphology appears not to be entirely unaffected by adjacent defects.

Expression of Tc-lab in wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Tc-lab expression appears prematurely in Tc-kni RNAi embryos (panels G, H, I; compare to equivalent stage wildtype embryos in panels A, B, C respectively). In Tc-kni RNAi embryos Tc-lab expression is always present but somewhat disturbed, including lack of median enlargement (H, I, L, compared to wildtype embryos in panels D, F) or lateral reduction (I, J, K, compare to wildtype embryos in panels D, E). See text for further details. The red background staining in each panel is weak FastRed signal for Tc-wg.

We also examined the expression of another marker for the intercalary segment in Tc-kniRNAi embryos, the second order regulator Tc-collier (Tc-col), also called Tc-knot. Tc-col acts downstream of Tc-lab and is required for wildtype expression of Tc-en in the intercalary segment [31]. Aside from a slight delay in the initial appearance of the Tc-col expression domain in early embryos (Figure 7 compare B, C with A) we found no evidence of strong disruption of Tc-col expression in a Tc-kniRNAi background (Figure 7). Besides, this staining confirmed the identity, and wildtype appearance, of the intercalary spots of Tc-en in late elongating and early fully elongated embryos (black asterisk in panels K, L, N and O in Figure 7).

Expression of Tc-col and Tc-en in wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi embryos. Abnormalities in Tc-en expression in Tc-kni RNAi embryos are similar to those seen in Figure 2 and described in the text. The appearance of the Tc-col domain in early germband embryos may be slightly delayed following Tc-kni RNAi (compare panels B, C to panel A). Apart from minor irregularities, the Tc-col expression domain is not strongly altered in Tc-kni RNAi embryos (compare wildtype to Tc-kni RNAi embryos in panels D-O). The co-expression of Tc-col and Tc-en in a medial region of the head in mid-to-late germband embryos (black asterisk in panels J-L, N-O, obscured by antennae in M) confirms the identity and presence of intercalary Tc-en expression in a Tc-kni RNAi background. White arrowheads: Tc-en antennal stripe. Black arrows: Tc-en mandibular stripe. Black arrowheads: Tc-en maxillary stripe. Red arrows: Residual Tc-en expression associated with structures at the base of the antennae. Ventral views, and anterior towards the top, in all panels.

The Drosophila head gap genes lead to the loss of entire adjacent segments but their Tribolium orthologues do not fit this definition [36]. Similarly, taken together, our data (summarized in Figure 8) show that Tc-kni cannot be considered a canonical head gap gene, because Tc-kni function is only required for the posterior parts of the antennal and mandibular segments (the regions shaded grey in Figure 8A). Moreover, Tc-kni is not required for the formation of the intercalary segment, which lies between the affected antennal and mandibular segments. Intercalary segment polarity gene expression is instead likely dependent on a conserved pathway involving Tc-lab and Tc-col[31, 32]. Overall, our data confirm that the regulatory networks underlying the establishment of the anterior head segments have diverged significantly between Tribolium and Drosophila, involving changing roles for knirps, buttonhead and empty spiracles homologues [36].

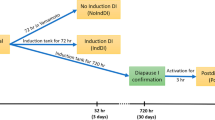

Schematic diagrams summarizing the expression of Tribolium head genes in wildtype and Tc-kniRNAiembryos. Changes in marker gene expression following Tc-kni RNAi are consistent with a failure to specify and form posterior antennal and mandibular segmental regions (marked in grey in A, and deleted in B). Deletion of these regions explains the absence of segment polarity gene expression in antennal and mandibular segments, the deletion of posterior regions of the ocular/antennal domains of Tc-gsc and Tc-lim1 at early stages, the reduced width of the Tc-Dfd domain, and the reduction in distance between antennal, mandibular and/or maxillary domains of Tc-lim1, Tc-ems and/or Tc-slp-1. Abnormalities in the expression patterns of the genes bounded by the horizontal doted lines are most apparent in lateral regions of the germband. Additional defects affecting the maxillary segment have to be assumed to explain the fusion of respective Tc-ems and Tc-slp stripes. These could be due to aberrant morphogen signaling of the mandibular parasegment boundary. In Tc-kni RNAi, the antennal parasegment boundary is never established while our model assumes that the posterior of the mandibular segment is lost later due to disturbance of the wg/hh/en regulatory loop. Lightly shaded regions represent early aspects of expression that do not persist to later stages. See Figure 10 and text for details.

The Tc-kniphenotype is due to a failure to correctly specify cell fates

We decided to check whether missing head regions in Tc-kni knockdown and mutant embryos were lost due to a failure to maintain already specified tissue - which might be indicated by high levels of cell death - or through the failure to specify cells to their correct developmental fate. Using TUNEL staining, we did not detect any apoptosis in either the blastoderm (see Additional file 3) or early germband stages (see Additional file 4) in Tc-kniRNAi embryos. In later germband stages there were a few apoptotic cells detectable in the head (as well as the posterior growth zone), but no more than in wild-type embryos, and there was no specific pattern of apoptosis that would indicate the loss of the tissues in question, namely the posterior portions of the antennal and mandibular segments (see Additional files 3 and 4). Thus, the lack of antennae and mandibles in Tc-kniRNAi and Tc-kniatl larvae is not due to tissue degeneration, but rather the failure to specify the respective segmental regions.

The posterior border of the anterior Tc-kni expression domain is regulated by Tc-even-skipped

In the Tribolium blastoderm, expression of Tc-kni and the pair rule genes occurs at the same time, opening the possibility Tc-kni could be regulated by pair rule genes. Indeed, in Tc-eveRNAi blastoderm embryos, we found that the anterior domain of Tc-kni expression expanded into more posterior regions (Figure 9: compare panel B to panel A). In contrast, expression defects in this Tc-kni mandibular domain were not seen in Tc-oddRNAi or Tc-runRNAi germbands (Figure 9: compare panels C and D with A). This is consistent with the first pair-rule and/or segmental stripe of Tc-eve expression being required to set the posterior boundary of mandibular Tc-kni expression.

Tc-kni is regulated by Tc-eve . The Tc-kni head expression domain, which covers the anterior compartment of the mandibular segment (bounded by black horizontal lines in panels A, C, D) extends posteriorly (arrowhead in panel B), in a Tc-eve RNAi background, but not in Tc-odd RNAi (panel C) or Tc-run RNAi (panel C) embryos. This is consistent with Tc-eve expression in the posterior compartment of the mandibular segment setting the posterior boundary of the Tc-kni head expression domain.

Head and trunk segmentation gene networks cooperate to establish the mandibular segment in a different way in Tribolium and Drosophila

In Drosophila, the anterior head gene regulatory network (through btd, col and cnc) and the gnathal/trunk regulatory gene network (through eve) cooperate to pattern aspects of the mandibular segment (Figure 10A and [11, 12]). In this study we provide evidence that this is also true in Tribolium. Both Tc-eve and Tc-kni RNAi lead to the failure to properly maintain mandibular Tc-en stripe expression and as a result to loss of the mandible itself (this study and [24, 43]). In our model (Figure 10B) Tc-kni contributes to the activation of mandibular Tc-wg expression. This interaction could be direct because the respective expression patterns overlap. Tc-eve in turn could be directly involved in activating Tc-hh and Tc-en within its anteriormost expression domain. Subsequently, the interactions of the Wnt and hh pathways ensure maintenance of the parasegement boundary. In the absence of Tc-kni expression, Tc-eve still partially initiates Tc-en/Tc-hh expression in the posterior compartment, which leads to partial initiation of Tc-wg in the anterior adjacent cells (through Hedgehog signaling). However, absence of Tc-kni leads to failure to maintain Tc-wg expression, and as a result failure to maintain Tc-en expression in posterior adjacent cells (through Wingless signaling). Interestingly, in Drosophila, the maintenance of en and wg expression in the mandibular segment appears more interdependent in dorsal regions [13]. The same might also be true in Tribolium, since both Tc-en and Tc-wg expression is maintained more often in medial (i.e. ventral) regions in Tc-kni mutant and knockdown embryos. Taken together, it appears to be a conserved feature of insects that two systems cooperate in patterning the mandible, but the molecular details of this cooperation have diverged significantly between Drosophila and Tribolium (Figure 10).

The genetic interactions that help establish the PS0/PS1 parasegmental boundary in Drosophila and Tribolium . In Drosophila (A), expression of the mandibular engrailed (en) stripe is dependent on the activity of buttonhead (btd) [9]. In contrast, in Tribolium (B), expression of the mandibular Tc-en stripe is dependent on the combined activity of Tc-kni in the anterior compartment (PS0) (this study) and Tc-eve in the posterior compartment (PS1) [24]. Cap‘n’collar (Cnc) may limit positive regulation of hh by col to the intercalary segment by physically interacting with Col in the mandibular segment [22]. The interactions between the segment polarity genes in the mandibular segment in Tribolium are assumed from what is known in Drosophila[13]. Black symbols: Possible direct genetic interactions. Gray symbols: Direct interactions shown in [22].

Conclusions

In this study we show that anterior regions of the antennal and mandibular segment, as well as the intervening intercalary segment, are correctly specified in the absence of Tc-kni function. Moreover, we identify key differences in the role of Tc-kni in setting up the non-adjacent antennal and mandibular parasegment boundaries. We identify the pair-rule gene Tc-even-skipped as a potential positive regulatory input that enables the initial specification (but not maintenance) of the mandibular parasegmental boundary in the absence of Tc-kni function. We also present the first evidence that, as in Drosophila, head and trunk gene regulatory networks cooperate to specify the mandibular segment. However, our data, and those of others, point to significant divergence in the molecular interactions involved in mandibular patterning between Drosophila and Tribolium.

A recent study of the expression and function of head patterning genes in the hemimetabolous insect Oncopeltus fasciatus suggests that the developmental gene networks operating in Tribolium castaneum more closely resemble the ancestral insect condition, perhaps not surprisingly given the highly derived Drosophila larval head [59]. Indeed, recent data from a myriapod suggest that the developmental genetic basis of Tribolium larval head development might even closely resemble the ancestral arthropod condition [60, 61]. It will be interesting to see whether studies on other arthropods reveal an ancestral role for knirps-family homologues in head segmentation, which would imply ems and btd have usurped the role of knirps, and potentially other genes, in the lineage leading to Drosophila.

Methods

Antennalessmutant analysis

The antennaless mutant line was maintained as described by Berghammer et al.[62] and Maderspacher et al.[54]. The separation of offspring from single pair crosses was performed after three and six days of egg laying at 32°C and 25°C respectively. Cuticle preparations of mutant larvae were prepared as previously described [54]. Genomic DNA was extracted from individual L1 antennaless mutant and wildtype larvae by first removing flour and chorion by bleaching egg collections two times for four minutes in 100% bleach. Embryos were washed three times with extraction buffer (without proteinase K - see below), put individually into 0.5 ml cups and frozen at −20°C. 10 μl of extraction buffer was added (25 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 200 μg/ml proteinase K) and the embryos macerated with a pipette tip. After 90mins at 42°C, the preparations were shortly spun down and proteinase K was inactivated by three minutes at 95°C. Debris was spun down for two minutes at 14000 rpm and 8 μl of supernatant was transferred to new tubes. 4 μl were used for a 20 μl PCR reaction. The three Tc-kni exons were amplified by PCR using the following four primer combinations: ex1 fw 5′-ACATTCCCCACCATTGAAATCACA-3′; ex1 rev 5′-GGGTTAAGTTTCTCGGTATTGGGACTA-3′; ex2 fw 5′-CCTGTAATGTGTACAGTCACGAGCAG-3′; ex2 rev 5′-ATTCTTGCATCGGCCGAAGTTTACGT-3′; ex3A fw 5′-CGGAAGCTCTGTCAAACAATAATCTCA-3′; ex3A rev 5′-TCCAGGAACACCCGCTTGTTGA-3′; ex3B fw 5′-CGCCGACGTTTCTACCTCCTCA-3′; ex3B rev 5′-TCGACGCTAATAGCTGCCATCATC-3′. Sequencing of the PCR products was performed by Macrogen (Korea).

Expression analysis

Fixation of embryos and enzymatic single and double in situ hybridizations were carried out according to established protocols [63]. For double in situ hybridizations Fastred ® (Sigma) was sometimes used (e.g. for Tc-wg) in place of INT/BCIP (Roche 11-681-460-001) [63]. Probes for in situ hybridization were prepared using either the Digoxigenin RNA Labeling Kit or Fluorescein RNA Labeling Kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim) following established protocols and the manufacturers instructions [63]. The DNA templates used for RNA probe production were in some cases (i.e. for probes detecting Tc-ems, Tc-slp-1, Tc-wg, Tc-eve, Tc-gsc, Tc-hh, Tc-lab, Tc-lim1, Tc-odd, Tc-run) produced by PCR-amplifying DNA fragments of the gene of interest from clones using appropriate vector primers (T3, T7, SP6). In other cases (i.e. for probes detecting Tc-en, Tc-col, Tc-Dfd) clones containing a fragment of the gene of interest were used directly as templates following 5′ linearization using an appropriate restriction enzyme. Clones and information are available on request. Following in situ hybridizations, nuclei in blastoderm and early germband embryos were sometimes counterstained using Hoechst 33258 (Additional file 2), Hoechst 33342 (Additional file 3) or DAPI (Figures 1, 2 and 7).

Parental RNAi

Adult or pupal parental RNAi was carried out using established protocols [64]. dsRNA was produced using the T7 and SP6 MEGAscript High Yield Transcription Kits (Ambion). Template DNA was either PCR-amplified using the vector insert flanking primers T7: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′ and T7-Sp6: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGATTTAGGTGAACACTATAGA-3′) or by using a stock of the linearized plasmid. In this case the antisense and sense strands were amplified separately, and later the ssRNA combined in equimolar amounts. A concentration of between 2 and 4.3 μg/μl of Tc-kni dsRNA was injected in each experiment, since this concentration range has been previously shown to consistently produce fully penetrant Tc-kni RNAi phenotypes [43]. To knockdown Tc-eve, Tc-odd and Tc-runt concentrations of between 2 and 3.5μg/μl of dsRNA were used.

TUNEL staining

Fixed embryos stored in methanol at −20°C were gradually rehydrated by washing in 70% methanol/PBT, then 50% methanol/PBT, then 30% methanol/PBT and finally 100% PBT (PBS + 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20). Embryos were then incubated for six minutes in 1 ml of PBT + 0.5 μl proteinase K (15 mg/ml) and subsequently washed several times in PBT. Embryos were then post-fixed in 1 ml of PBT + 125 μl of formaldehyde (37%) for 20 minutes, before being washed three times in PBT. At this point, positive control embryos were washed three time in DNaseI buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.5, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 6 mM MgCl2), incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in DNaseI buffer with 0.06 U DNaseI per microlitre of buffer, before being washed several times in PBT. All embryos were then incubated for 20 minutes in 0.1% sodium borohydride. During incubation, the embryos were gently shaken several times. The sodium borohydride was then removed by repeated washing with TdT buffer (140 mM cacodylic acid, 1 mM cobalt chloride, 30 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.2). Embryos were then incubated at 37°C in TdT buffer containing 20 μM DIG-UTP and 0.3 U/μl terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (Sigma). In the case of negative control embryos, the TdT was omitted. All embryos were then washed three times for five minutes in TBST (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH7.4, 0.1% Tween-20) at room temperature, before being incubated at 70°C for 20 minutes in TBST. Embryos were then washed three times for five minutes in PBT, before being incubated in PAS (PBT with 10 mg/ml bovine albumine (BSA) and 2% sheep serum) for one hour. Embryos were then incubated in PAS with anti-Dig antibody (1:2000) for one hour. This was followed by several washes in PBT for a total of two hours. Embryos were stored overnight at 4°C in PBT before being washed for 30 minutes at room temperature in PBT prior to NBT/BCIP staining. The staining was stopped by repeated washing in PBT and the embryos stored at 4°C in 1 ml of PBT + 125 μl of formaldehyde (37%).

Microscopy

Most in situ hybridization stained preparations were imaged on an Axioplan 2 photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH, Jena) using a polarized light (DIC) filter with low Normaski contrast (ImageProPlus, Version 5.0 .2.9, MediaCybernetics). For clear detection of the fluorescence signal of the Fastred® color reaction the filter set No. 43 (Cy3) from Zeiss, and a mercury vapor lamp HBO100 as a light source, was used. For the detection of Hoechst 33258 and Hoechst 33342 signal the filter set No. 49 from Zeiss (DAPI filter), and a mercury vapor lamp as the light HBO100 source, was used. A few in situ hybridization stained preparations were imaged on a Leica MZ16F epifluorescence stereoscope with a DFC300FX digital camera (images in Figures 2 and 7). Larval cuticles were imaged using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss) and processed as described [65].

Availability of supporting data

The data set supporting the results of this article is included within the article (and its additional files).

References

Posnien N, Schinko JB, Kittelmann S, Bucher G: Genetics, development and composition of the insect head–a beetle’s view. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010, 39: 399-410. 10.1016/j.asd.2010.08.002.

Scholtz G, Edgecombe GD: The evolution of arthropod heads: reconciling morphological, developmental and palaeontological evidence. Dev Genes Evol. 2006, 216: 395-415. 10.1007/s00427-006-0085-4.

Rogers BT, Kaufman TC: Structure of the insect head in ontogeny and phylogeny: a view from Drosophila. Int Rev Cytol. 1997, 174: 1-84.

Budd GE: A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature. 2002, 16: 271-275.

Schmidt-Ott U, González-Gaitán M, Jäckle H, Technau GM: Number, identity, and sequence of the Drosophila head segments as revealed by neural elements and their deletion patterns in mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91: 8363-8367. 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8363.

Haas MS, Brown SJ, Beeman RW: Pondering the procephalon: the segmental origin of the labrum. Dev Genes Evol. 2001, 211: 89-95. 10.1007/s004270000128.

Rempel GJ: The evolution of the insect head: the endless dispute. Quaest Entomol. 1975, 11: 7-25.

St Johnston D, Nüsslein-Volhard C: The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1992, 68: 201-219. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-P.

Cohen SM, Jurgens G: Mediation of Drosophila head development by gap-like segmentation genes. Nature. 1990, 346: 482-485. 10.1038/346482a0.

Mohler J: Spatial regulation of segment polarity gene expression in the anterior terminal region of the Drosophila blastoderm embryo. Mech Dev. 1995, 50: 151-161. 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00332-H.

Crozatier M, Valle D, Dubois L, Ibnsouda S, Vincent A: Collier, a novel regulator of Drosophila head development, is expressed in a single mitotic domain. Curr Biol. 1996, 6: 707-718. 10.1016/S0960-9822(09)00452-7.

Crozatier M, Valle D, Dubois L, Ibnsouda S, Vincent A: Head versus trunk patterning in the Drosophila embryo; collier requirement for formation of the intercalary segment. Development. 1999, 126: 4385-4394.

Gallitano-Mendel A, Finkelstein R: Novel segment polarity gene interactions during embryonic head development in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1997, 192: 599-613. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8753.

Schmidt-Ott U, Technau GM: Expression of en and wg in the embryonic head and brain of Drosophila indicates a refolded band of seven segment remnants. Development. 1992, 116: 111-125.

Vincent A, Blankenship JT, Wieschaus E: Integration of the head and trunk segmentation systems controls cephalic furrow formation in Drosophila. Development. 1997, 124: 3747-3754.

Grossniklaus U, Cadigan KM, Gehring WJ: Three maternal coordinate systems cooperate in the patterning of the Drosophila head. Development. 1994, 120: 3155-3171.

Hülskamp M, Tautz D: Gap genes and gradients–the logic behind the gaps. Bioessays. 1991, 13: 261-268. 10.1002/bies.950130602.

Wimmer EA, Cohen SM, Jäckle H, Desplan C: Buttonhead does not contribute to a combinatorial code proposed for Drosophila head development. Development. 1997, 124: 1509-1517.

Gallitano-Mendel A, Finkelstein R: Ectopic orthodenticle expression alters segment polarity gene expression but not head segment identity in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Biol. 1998, 199: 125-137. 10.1006/dbio.1998.8917.

Schöck F, Reischl J, Wimmer E, Taubert H, Purnell BA, Jäckle H: Phenotypic suppression of empty spiracles is prevented by buttonhead. Nature. 2000, 405: 351-354. 10.1038/35012620.

Ntini E, Wimmer E: Unique establishment of procephalic head segments is supported by the identification of cis-regulatory elements driving segment-specific segment polarity gene expression in Drosophila. Dev Genes Evol. 2011, 221: 1-16. 10.1007/s00427-011-0354-8.

Ntini E, Wimmer EA: Second order regulator Collier directly controls intercalary-specific segment polarity gene expression. Dev Biol. 2011, 360: 403-414. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.035.

Brown SJ, Shippy TD, Miller S, Bolognesi R, Beeman RW, Lorenzen MD, Bucher G, Wimmer EA, Klingler M: The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera): a model for studies of development and pest biology. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2009, 2009: pdb emo126-

Choe CP, Miller SC, Brown SJ: A pair-rule gene circuit defines segments sequentially in the short-germ insect Tribolium castaneum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 6560-6564. 10.1073/pnas.0510440103.

Choe CP, Brown SJ: Evolutionary flexibility of pair-rule patterning revealed by functional analysis of secondary pair-rule genes, paired and sloppy-paired in the short-germ insect, Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol. 2007, 302: 281-294. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.037.

Choe CP, Brown SJ: Genetic regulation of engrailed and wingless in Tribolium segmentation and the evolution of pair-rule segmentation. Dev Biol. 2009, 325: 482-491. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.037.

Farzana L, Brown SJ: Hedgehog signaling pathway function conserved in Tribolium segmentation. Dev Genes Evol. 2008, 218: 181-192. 10.1007/s00427-008-0207-2.

Brown SJ, Patel NH, Denell RE: Embryonic expression of the single Tribolium engrailed homolog. Dev Genet. 1994, 15: 7-18. 10.1002/dvg.1020150103.

Oppenheimer DI, MacNicol AM, Patel NH: Functional conservation of the wingless-engrailed interaction as shown by a widely applicable baculovirus misexpression system. Curr Biol. 1999, 9: 1288-1296. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80050-0.

Sarrazin AF, Peel AD, Averof M: A segmentation clock with two-segment periodicity in insects. Science. 2012, 336: 338-341. 10.1126/science.1218256.

Schaeper ND, Pechmann M, Damen WGM, Prpic NM, Wimmer E: Evolutionary plasticity of collier function in head development of diverse arthropods. Dev Biol. 2010, 344: 363-376. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.001.

Posnien N, Bucher G: Formation of the insect head involves lateral contribution of the intercalary segment, which depends on Tc-labial function. Dev Biol. 2010, 338: 107-116. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.010.

Economou AD, Telford MJ: Comparative gene expression in the heads of Drosophila melanogaster and Tribolium castaneum and the segmental affinity of the Drosophila hypopharyngeal lobes. Evol Dev. 2009, 11: 88-96. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00305.x.

Nagy LM, Carroll S: Conservation of wingless patterning functions in the short-germ embryos of Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 1994, 367: 460-463. 10.1038/367460a0.

Kittelmann S, Ulrich J, Posnien N, Bucher G: Changes in anterior head patterning underlie the evolution of long germ embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2013, 374: 174-184. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.11.026.

Schinko JB, Kreuzer N, Offen N, Posnien N, Wimmer EA, Bucher G: Divergent functions of orthodenticle, empty spiracles and buttonhead in early head patterning of the beetle Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera). Dev Biol. 2008, 317: 600-613. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.005.

Schoppmeier M, Fischer S, Schmitt-Engel C, Löhr U, Klingler M: An ancient anterior patterning system promotes caudal repression and head formation in ecdysozoa. Curr Biol. 2009, 19: 1811-1815. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.026.

Stauber M, Jackle H, Schmidt-Ott U: The anterior determinant bicoid of Drosophila is a derived Hox class 3 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 3786-3789. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3786.

Brown S, Fellers J, Shippy T, Dennell R, Stauber M, Schmidt-Ott U: A strategy for mapping bicoid on the phylogenetic tree. Curr Biol. 2001, 11: R43-R44. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00007-0.

Fu J, Posnien N, Bolognesi R, Fischer TD, Rayl P, Oberhofer G, Kitzmann P, Brown SJ, Bucher G: Asymmetrically expressed axin required for anterior development in Tribolium. PNAS. 2012, 109: 7782-7786. 10.1073/pnas.1116641109.

Kotkamp K, Klingler M, Schoppmeier M: Apparent role of Tribolium orthodenticle in anteroposterior blastoderm patterning largely reflects novel functions in dorsoventral axis formation and cell survival. Development. 2010, 137: 1853-1862. 10.1242/dev.047043.

Schröder R: The genes orthodenticle and hunchback substitute for bicoid in the beetle Tribolium. Nature. 2003, 422: 621-625. 10.1038/nature01536.

Cerny AC, Grossmann D, Bucher G, Klingler M: The Tribolium ortholog of knirps and knirps-related is crucial for head segmentation but plays a minor role during abdominal patterning. Dev Biol. 2008, 321: 284-294. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.527.

Oro AE, Umesono K, Evans RM: Steroid hormone receptor homologs in development. Development. 1989, 107: 133-140.

Rothe M, Nauber U, Jäckle H: Three hormone receptor-like Drosophila genes encode an identicle DNA-binding finger. EMBO J. 1989, 8: 3087-3094.

Gerwin N, La Rosée A, Sauer F, Halbritter H, Neumann M, Jäckle H, Nauber U: Functional and conserved domains of the Drosophila transcription factor encoded by the segmentation gene knirps. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14: 7899-7908.

Naggan Perl T, Schmid BG, Schwirz J, Chipman AD: The Evolution of the knirps Family of Transcription Factors in Arthropods. Mol Biol Evol. 2013, 30: 1348-1357. 10.1093/molbev/mst046.

Rothe M, Wimmer EA, Pankratz MJ, González-Gaitán M, Jäckle H: Identical transacting factor requirement for knirps and knirps-related gene expression in the anterior but not in the posterior region of the Drosophila embryo. Mech Dev. 1994, 46: 169-181. 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90069-8.

González-Gaitán M, Rothe M, Wimmer EA, Taubert H, Jäckle H: Redundant functions of the genes knirps and knirps-related for the establishment of anterior Drosophila head structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91: 8567-8571. 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8567.

Nauber U, Pankratz MJ, Kienlin A, Seifert E, Klemm U, Jäckle H: Abdominal segmentation of the Drosophila embryo requires a hormone receptor-like protein encoded by the gap gene knirps. Nature. 1988, 336: 489-492. 10.1038/336489a0.

Riddihough G, Ish-Horowicz D: Individual stripe regulatory elements in the Drosophila hairy promotor respond to maternal, gap and pair-rule genes. Genes Dev. 1991, 5: 840-854. 10.1101/gad.5.5.840.

Pankratz MJ, Seifert E, Gerwin N, Billi B, Nauber U, Jäckle H: Gradients of Krüppel and knirps gene products direct pair-rule gene stripe patterning in the posterior region of the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1990, 61: 309-317. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90811-R.

Clyde DE, Corado MS, Wu X, Pare A, Papatsenko D, Small S: A self-organizing system of repressor gradients establishes segmental complexity in Drosophila. Nature. 2003, 426: 849-853. 10.1038/nature02189.

Maderspacher F, Bucher G, Klingler M: Pair-rule and gap gene mutants in the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev Genes Evol. 1998, 208: 558-568. 10.1007/s004270050215.

Handel K, Grünfelder CG, Roth S, Sander K: Tribolium embryogenesis: a SEM study of cell shapes and movements from blastoderm to serosal closure. Dev Genes Evol. 2000, 210: 167-179. 10.1007/s004270050301.

Posnien N, Koniszewski ND, Hein HJ, Bucher G: Candidate gene screen in the red flour beetle Tribolium reveals six3 as ancient regulator of anterior median head and central complex development. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7: e1002416-10.1371/journal.pgen.1002416.

Bucher G, Scholten J, Klingler M: Parental RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera). Curr Biol 12. 2002, 12: R85-R86. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00666-8.

Nie W, Stronach B, Panganiban G, Shippy T, Brown S, Denell R: Molecular characterization of Tclabial and the 3′ end of the Tribolium complex. Dev Genes Evol. 2001, 211: 244-251. 10.1007/s004270100151.

Birkan M, Schaeper ND, Chipman AD: Early patterning and blastoderm fate map of the head in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus. Evol Dev. 2011, 13: 436-447. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00497.x.

Janssen R, Budd GE, Damen WGM: Gene expression suggests conserved mechanisms patterning the heads of insects and myriapods. Dev Biol. 2011, 357: 64-72. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.670.

Janssen R, Damen WGM, Budd GE: Expression of collier in the premandibular segment of myriapods: support for the traditional Atelocerata concept or a case of convergence?. BMC Evol Biol. 2011, 11: 50-10.1186/1471-2148-11-50.

Berghammer A, Bucher G, Maderspacher F, Klingler M: A system to efficiently maintain embryonic lethal mutations in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev Genes Evol. 1999, 209: 382-389. 10.1007/s004270050268.

Schinko J, Posnien N, Kittelmann S, Koniszewski N, Bucher G: Single and double whole-mount in situ hybridization in red flour beetle (Tribolium) embryos. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2009, 2009: pdb prot5258-

Posnien N, Schinko J, Grossmann D, Shippy TD, Konopova B, Bucher G: RNAi in the red flour beetle (Tribolium). Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2009, 2009: pdb prot5256-

Wohlfrom H, Schinko JB, Klingler M, Bucher G: Maintenance of segment and appendage primordia by the Tribolium gene knödel. Mech Dev. 2006, 123: 430-439. 10.1016/j.mod.2006.04.003.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michalis Averof for the use of reagents and laboratory space and Ernst A. Wimmer for support. This work was funded by Deutsche Forschunggemeinschaft DFG (BU-1443/3-1). MK’s screen for segmentation mutants was funded by DFG grant Kl656/2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AP performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper, DG, JS, FR and GO performed experiments and analyzed the data, JS supervised experiments and analyzed the data, AG drafted the paper, MK identified the atl mutant, and GB designed the study and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Andrew D Peel, Julia Schanda, Daniela Grossmann contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12861_2013_736_MOESM1_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 1: The sensitivity of Tc-kni RNAi head and abdominal larval phenotypes to temperature. (A, B) Head phenotypes are more severe at higher temperatures. Note the higher frequency of strong head phenotypes (up to ~90% vs. circa 70%) and lower frequency of weak head phenotypes (0% at some time points at 32°C) following Tc-kni RNAi carried out at 32°C compared to 25°C. Larvae exhibiting strong head phenotypes lacked both antennae and mandibles, larvae exhibiting medium phenotypes possessed at least one antenna and larvae exhibiting weak phenotypes exhibited at least one antenna and mandibles. (C) The frequency of larval head phenotypes decreases with time post Tc-kni dsRNA injection. (D, E) In contrast to head phenotypes, abdominal phenotypes showed an unusual reverse sensitivity with respect to temperature and time following Tc-kni RNAi injection. Abdominal phenotypes were more common following Tc-kni parental RNAi carried out at 25°C compared to 32°C (compare height of blue bars in panel D vs. panel E). Abdominal phenotypes showed the unusual characteristic of increasing in frequency with time post Tc-kni dsRNA injection. (JPEG 711 KB)

12861_2013_736_MOESM2_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 2: Tc-kni is not expressed in antennaless embryos. Wildtype and antennaless blastoderm (panels A-D) and early germband (panels E-H) embryos co-stained with a mix of Tc-kni and Tc-cad probes detected with the same colour reaction. A probe against Tc-cad was used to control against the possibility that the absence of Tc-kni signal in antennaless embryos was due to technical problems. Blastoderm embryos were stained with Hoechst 33258 (A’-D’) in order to identify similar stage embryos. In antennaless blastoderm embryos, a block of signal (bounded by white lines in panels A, C) corresponding to the anterior head Tc-kni expression domain is missing, whereas the posterior domain of Tc-cad expression is detected. In antennaless early germband embryos the anterior mandibular stripe of Tc-kni expression (black arrowhead in panels E, G) is missing, whereas the posterior growth zone domain of Tc-cad expression is detected. Similar experiments using a Tc-otd probe as control proved that the posterior Tc-kni expression domain is also missing in antennaless blastoderm and germband embryos (data not shown). Panels A-D’: Lateral views, anterior to the left. Panels E-H: Ventral views, anterior to the top. (JPEG 859 KB)

12861_2013_736_MOESM3_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 3: TUNEL stained wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi blastoderm stage embryos. DAPI staining (A’-F’) was used to identify wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi blastoderm embryos of similar stages. No apoptotic nuclei were observed in wildtype or Tc-kni RNAi blastoderm embryos. (JPEG 645 KB)

12861_2013_736_MOESM4_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 4: TUNEL stained wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi germband stage embryos. Apoptotic nuclei were not observed in wildtype or Tc-kni RNAi early germband stage embryos (A-F). A few apoptotic nuclei (arrowheads in panels G-J) were observed in mid-elongation (G-H), late-elongation (I-J) and fully elongated (K-L) wildtype and Tc-kni RNAi germband embryos. However, levels of apoptotic nuclei were no higher in Tc-kni RNAi germband embryos when compared to controls, and apoptotic nuclei were not concentrated in regions within which the antennal and mandibular segments should or would develop. Note that in some cases (panels C, E, G, I, N) TUNEL reactions were developed for much longer than needed to detect apoptotic nuclei, leading to background staining. Note that apoptotic nuclei can nevertheless be distinguished from background (e.g. panels G, I). (JPEG 1 MB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Peel, A.D., Schanda, J., Grossmann, D. et al. Tc-knirps plays different roles in the specification of antennal and mandibular parasegment boundaries and is regulated by a pair-rule gene in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. BMC Dev Biol 13, 25 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-13-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-13-25