Abstract

In Drosophila, maintenance of parasegmental boundaries and formation of segmental grooves depend on interactions between segment polarity genes. Wingless and Engrailed appear to have similar roles in both short and long germ segmentation, but relatively little is known about the extent to which Hedgehog signaling is conserved. In a companion study to the Tribolium genome project, we analyzed the expression and function of hedgehog, smoothened, patched, and cubitus interruptus orthologs during segmentation in Tribolium. Their expression was largely conserved between Drosophila and Tribolium. Parental RNAi analysis of positive regulators of the pathway (Tc-hh, Tc-smo, or Tc-ci) resulted in small spherical cuticles with little or no evidence of segmental grooves. Segmental Engrailed expression in these embryos was initiated but not maintained. Wingless-independent Engrailed expression in the CNS was maintained and became highly compacted during germ band retraction, providing evidence that derivatives from every segment were present in these small spherical embryos. On the other hand, RNAi analysis of a negative regulator (Tc-ptc) resulted in embryos with ectopic segmental grooves visible during germband elongation but not discernible in the first instar larval cuticles. These transient grooves formed adjacent to Engrailed expressing cells that encircled wider than normal wg domains in the Tc-ptc RNAi embryos. These results suggest that the en–wg–hh gene circuit is functionally conserved in the maintenance of segmental boundaries during germ band retraction and groove formation in Tribolium and that the segment polarity genes form a robust genetic regulatory module in the segmentation of this short germ insect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ontogenic stage at which the body plans of animals belonging to the same phylum reach maximum morphological similarity is called the phylotypic stage. In insects and other arthropods, the phylotypic stage is the elongated germband at which the three germ layers have formed and segments are morphologically evident along the entire anterior–posterior axis (Sander 1997). In Drosophila, segment polarity genes, most of which are components of two major signal transduction pathways (the Wingless and Hedgehog signaling pathways), control the formation of grooves between segments and anterior–posterior patterning within each segment. Initially, pair-rule genes activate engrailed (en) expression at the anterior boundary of each parasegment and wingless (wg) at the posterior boundary DiNardo and O'Farrell (1987; Howard et al. 1988; Ingham et al. 1988). Engrailed protein activates expression of hedgehog (hh), which encodes a secreted protein that signals to surrounding cells (Hidalgo and Ingham 1990; Ingham and Hidalgo 1993). Hh signaling leads to the continued activation of wg, whose secreted protein product is necessary for the continued activation of en. This positive feedback loop ensures the interdependence of these three genes for the maintenance of each other’s expression until embryonic stage 9–10 (Forbes et al. 1993). At the end of stage 10, en expression becomes independent of wg, and it is around this stage that segmental boundaries are morphologically visible at the posterior edge of cells expressing en and hh.

Evidence that this segment polarity network might be conserved is primarily based on the expression patterns of en, wg, and more recently, Hh pathway component genes in other insects as well as non-insect arthropods and annelids (Patel et al. 1989; Brown et al. 1994; Kraft and Jackle 1994; Nagy and Carroll 1994; Grbic et al. 1996; Peterson et al. 1998; Damen 2002; Dhawan and Gopinathan 2003; Simonnet et al. 2004). There is also limited data suggesting this network is functionally conserved among insects. Ectopic expression of Drosophila wg in Tribolium induces ectopic en in the anterior half of the parasegment suggesting functional conservation of the wg–en interaction (Oppenheimer et al. 1999). wg and/or en have been implicated by RNAi analyses in the proper formation of segmental boundaries in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus faciatus (Angelini and Kaufman 2005), the honey bee Apis mellifera (Beye et al. 2002), the blowfly Lucilia sericata (Mellenthin et al. 2006) and the beetle Tribolium (Ober and Jockusch 2006). While RNAi analysis of wg and hh in the cricket Gryllus (Miyawaki et al. 2004) failed to reveal significant effects on segmentation, RNAi analysis of armadillo, a wg pathway component, does implicate wg signaling in segmentation in this short germ insect. In the long germ embryo of Drosophila, where all segments initiate virtually simultaneously, loss of any one of these three genes destabilizes the expression of the others and they eventually fade, resulting in shorter embryos that, in addition to the loss of segmental grooves, also show misspecified epidermal cell fates (Ingham et al. 1991; Forbes et al. 1993). We have investigated genes that encode the Hh-signaling pathway components hedgehog (hh), patched (ptc), smoothened (smo), and cubitus interruptus (ci) to determine whether they function with en and wg in the formation of segmental boundaries in this short germ band insect.

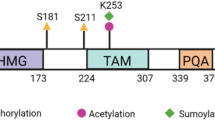

The Hh-signaling pathway is well-conserved between insects and vertebrates (Huangfu and Anderson 2006) and is thus likely to be conserved in Tribolium. The main components were first elucidated in Drosophila, where Hh is secreted by cells in the posterior compartment of embryonic segments and larval imaginal discs. It diffuses to the anterior compartment (Lee et al. 1992; Tabata et al. 1992; Tashiro et al. 1993) where the signal is controlled by two membrane proteins: Patched (Ptc), a twelve pass transmembrane protein (Hooper and Scott 1989; Nakano et al. 1989) and Smoothened (Smo), a seven pass transmembrane protein (Alcedo et al. 1996; van den Heuvel and Ingham 1996). In the absence of Hh signal, Ptc represses Smo activity (Chen and Struhl 1996). Signaling is initiated by binding of Hh to its receptor Ptc, which relieves this repression and allows Smo to signal to a multimeric complex inside the cell. This complex is composed of the serine threonine kinase Fused (Alves et al. 1998), the kinesin related protein Costal-2 (Sisson et al. 1997), a novel cytoplasmic protein Suppressor of fused (Monnier et al. 1998) and a zinc finger transcription factor Cubitus Interruptus (Ci; Motzny and Holmgren 1995). In unstimulated cells, this complex sequesters ci, inhibits nuclear import of the full-length 155 kDa protein and promotes its cleavage to generate an N-terminal 75-kDa form containing the Zn finger DNA-binding domain, which can enter the nucleus and repress transcription of Hh target genes (Aza-Blanc et al. 1997). When Hh signal is transduced, activation of Smo inhibits ci cleavage and activates the full-length protein, which then translocates to the nucleus, resulting in the transcription of Hh-responsive target genes including wg, ptc, gooseberry, and decapentaplegic (Alexandre et al. 1996; Dominguez et al. 1996; Hepker et al. 1997; Ingham and McMahon 2001).

Consistent with reports on other arthropods, we found that the expression patterns of hh, ci, smo, and ptc were largely conserved in Tribolium. Using RNAi to study the function of these genes during segmentation in Tribolium, we followed embryonic development in these embryos using En as a marker of segment development and integrity. When the Hh signal was depleted by RNAi, segments were specified normally in the posterior growth zone and the embryos elongated as fully as wild-type. En and wg expression in these embryos, although properly initiated, was not maintained and defects appeared during germ band retraction, resulting in tiny, sphere-shaped embryos lacking segmental grooves. On the other hand, overactivation of the pathway by ptc RNAi produced embryos with transient ectopic segmental grooves and embryonic cuticles with enlarged heads and thoracic appendages. All together, these results indicate that Hedgehog signaling is an essential component of the segment polarity network in Tribolium, which is necessary to maintain segmental integrity during germband retraction after the segments have been enumerated in the growth zone. The conserved function of an en–wg–hh gene circuit during segmentation suggests that the segment polarity genes constitute a robust gene regulatory module in this short germ insect.

Materials and methods

Beetle husbandry

Tribolium castaneum strain GA-1 was reared in whole wheat flour supplemented with 5% dried yeast at 30 C (Beeman et al. 1989).

Identification of hedgehog pathway component genes in the Tribolium genome

Partial cDNAs of tc-hh, tc-ci, tc-smo and tc-ptc, cloned into the pCR4TOPO vector (Invitrogen), were obtained from Y. Tomoyasu. Orthologs of each gene were identified in the annotation of the Tribolium genome (the Tribolium genome consortium, in review). The sequences of the partial cDNAs matched those deduced from the gene models with minor differences. hh, glean gene number tc01364 or NCBI mRNA accession number XM961615, is located on LG 2; smo, TC05545 or XM966834, is on LG 8; ci, TC03000 or XM965017, is on LG 3 and ptc, TC04745 or XM962700 is on LG 1 = X.

In situ hybridization and immunostaining

Whole mount in situ hybridizations were performed according to established protocols (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989). Expression of Engrailed in Tribolium embryos was determined using the α-Invected antibody, 4D9 which cross-reacts with Tc-En (Brown et al. 1994). Double staining for the different mRNAs in addition to En protein was performed simultaneously according to the protocol of Nagaso et al. (2001).

RNA interference (RNAi)

Templates for dsRNA synthesis were amplified as described (Tomoyasu et al. 2007). Double stranded RNA was synthesized using the T7 MEGAscript kit (Ambion) and purified using the MEGAclear kit (Ambion). Different amounts of dsRNA (Table 1) were mixed with injection buffer (5 mM KCl, 0.1 mM KPO4 pH 6.8) prior to injection. Parental RNAi was performed and affected embryos were analyzed as previously described (Bucher et al. 2002).

Microscopy and imaging

Stained embryos and larval cuticles were documented with a Nikon Digital DXM 1200F camera on an Olympus BX50 microscope using Nikon ACT-1 version 2.62 software. Brightness and contrast of all images were adjusted and some were placed on a white background using Adobe Photoshop 7.0.1 software.

Results

Expression patterns of Tc-hh, Tc-smo, and Tc-ci

Tc-hh transcripts are first detected in the presumptive head lobes on either side of the ventral mesoderm (arrowhead in Fig. 1a) and at the posterior end of the embryo. As the embryonic rudiment condenses, faint stripes of Tc-hh expression appear immediately posterior to the intense stripes in the head lobes and in the presumptive mandibular segment (arrowheads in Fig. 1b). Gnathal and trunk stripes appear in an anterior to posterior progression (Fig. 1c). Double staining for En expression revealed that Tc-hh and Tc-En are coexpressed in cells of the posterior compartment in each segment (Fig. 1d). During germband elongation, expression at the posterior end of the embryo resolves into spots on either side of the mesoderm and eventually into a ring surrounding the proctodeum (Fig. 1b–d and arrowhead in f). In the head, twin spots appear on either side of the presumptive stomodeum. As the head lobes mature, expression in the anterior region of the developing stomodeum increases (Fig. 1c,d and black arrowhead in e), while the anterior-most stripes of Tc-hh expression resolve into spots in the brain that overlap with the Tc-En-expressing cells (Fig. 1c,d and blue arrowhead in e). Expression at the posterior end of the embryo continues throughout germ band extension (Fig. 1b,d and f) eventually surrounding the proctodeum as it invaginates (Fig. 1f). As segments mature, Tc-hh expression at the ventral midline clears and Tc-hh is not expressed in the CNS. In total, there are three gnathal, three thoracic, and ten abdominal Tc-hh stripes with additional expression in the stomodeum, proctodeum, antennae, and brain (Fig. 1d).

Expression of Tc-hh, Tc-ci, and Tc-smo in Tribolium during segmentation. In these ventral views, anterior is to the left. a–c Tc-hh; d–f Tc-hh (purple) and Tc-En (gold); g–h Tc-smo; i–k Tc-ci; l, m Tc-ci (purple) and Tc-En (gold); a Anterior stripes of Tc-hh (arrowhead) in the presumptive head lobes of a blastoderm embryo. Expression at the posterior end of the embryo is not in the plane of focus. b Weak stripes appear in the antennal and mandibular segments (arrowheads) posterior to the dark stripes in the head lobes. Twin spots of expression flank the mesoderm at the posterior end of the embryo and near the stomodeum. c In addition to expression in the head lobes and antennae, three gnathal stripes and one trunk stripes appear in an elongating germband embryo. d Coexpression of Tc-En (gold) and Tc-hh (purple) in the posterior compartment of each segment. Note Tc-En expression at the ventral midline in the absence of Tc-hh. e–f Tc-hh expression in the stomodeum and the proctodeum (arrowheads) in the absence of Tc-En. Expression of Tc-hh in the head lobes has resolved into spots that overlap Tc-En expression (blue arrowhead). g Ubiquitous expression of Tc-smo in an early germ band embryo. h In an elongating germ band embryo, Tc-smo expression appears ubiquitous with some segmental modulation (arrowheads). i Expression of Tc-ci at the anterior edge of the head lobes (arrowhead) of a young germband embryo. j Gnathal stripes appear first in a slightly older embryo. Expression throughout the posterior region of the embryo fades anteriorly. k Wide Tc-ci stripes in the head lobes and antennal segments as well as in the gnathal and thoracic segments of an elongating germ band embryo. l Tc-En (gold) expression does not overlap Tc-ci (purple) expression in cells of the anterior compartment of each segment. m Enlarged view of a few thoracic segments from the embryo shown in l reveals a gap of two or three rows of cells anterior to the Tc-En stripes that do not express Tc-ci (arrowhead)

Tc-smo is expressed ubiquitously in the germband (Fig. 1g) in Tribolium. As the germ band elongates, expression appears to modulate slightly within each segment (arrowheads in Fig. 1h). smo transcripts are expressed in a similar manner in Drosophila (Alcedo et al. 1996).

Tc-ci expression is first detected at the anterior edge of each head lobe in the early embryonic rudiment (arrowhead in Fig. 1i). Dynamic expression of Tc-ci in the head lobes eventually resolves to a wedge of cells in the lateral eye field (Fig. 1j). Expression is detected in the labrum (Fig. 1l) and in a broad posterior region, which fades toward the anterior (Fig. 1j). As the germ band elongates, Tc-ci is expressed in a broad stripe in every segment in an anterior to posterior progression (Fig. 1i–k). Double staining for Tc-En indicates that Tc-ci is expressed in the anterior compartment where the anterior-most Tc-ci expressing cells are immediately posterior to the Tc-En-expressing cells of the preceding segment (Fig. 1m). Segmentally reiterated stripes of ci expression are also observed in the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori (Dhawan and Gopinathan 2002), the spider Cupiennius salei (Damen 2002), and the millipede Glomeris (Janssen et al. 2004), suggesting that the segmental expression of ci in the anterior region of each segment is conserved among arthropods. Closer examination of Tc-ci expression revealed a gap of two or three rows of cells immediately anterior of the Tc-En-expressing cells that do not express Tc-ci (Fig. lm). In contrast, expression of ci throughout the anterior compartment of each segment in Drosophila is thought to be essential to the function of the Hh-signaling pathway in maintaining wg expression (Orenic et al. 1990; Hepker et al. 1997). Expression of ci immediately anterior to En-expressing cells is conserved in the spider (Damen 2002), but has not been reported for Bombyx or Glomeris. Thus, it is not clear whether this unusual expression pattern is unique to Tribolium.

RNAi analysis of Tc-hh, Tc-smo, and Tc-ci

The conserved expression patterns of Tc-hh and Tc-smo are consistent with the hypothesis that the Hh function in segmentation is conserved in Tribolium, but the lack of Tc-ci gene expression in cells immediately anterior to Tc-hh is not. To determine whether the Hh-signaling pathway is required for proper segmentation, we performed parental RNAi analysis of these Hh pathway components. Three different amounts of Tc-hh and Tc-smo dsRNA were injected, which uncovered a range of hypomorphic phenotypes (Table 1). Similar RNAi phenotypes were produced for both genes, and the RNAi cuticles were classified into three different categories (Class I, II, and III) based on severity as listed in Table 1. Regardless of the severity, none of the RNAi embryos hatched and the cuticle had to be dissected out of the vitelline membranes. Class I cuticles display the weakest phenotypes, in which the head is severely reduced and contains only rudimentary limb structures. The legs are present but slightly warped, and segmental grooves in the abdomen are occasionally fused but all eight abdominal segments are present (Fig. 2b (Tc-hh), f (Tc-smo)). Class II cuticles are small and spherical, with a large protuberance at the anterior end and three small warped pairs of limbs. The presence of the spiracle on the second thoracic segment (arrowhead in Fig. 2c and g) allowed us to identify these structures as rudimentary legs. The small amount of cuticle posterior to these small warped legs is smooth and lacked any abdominal features (Fig. 2c (Tc-hh), g (Tc-smo)). The most severely affected embryos, Class III, produced small spherical cuticles with a large protuberance at the anterior end and no obvious head structures or thoracic limbs (Fig. 2d (Tc-hh), h (Tc-smo)). These cuticles are very smooth on all sides, with no sign of grooves and are quite small relative to the size of similarly aged wild-type cuticles (Fig. 2a Tc-hh, e Tc-smo). The head and gnathal appendages appear to be more sensitive to the depletion of Tc-hh or Tc-smo than the legs, as even in the weakly affected individuals the head, including gnathal segments, failed to form properly (Fig. 2b,f).

Tc-hh, Tc-smo, and Tc-ci RNAi phenotypes in first instar larval cuticles. a–d Tc-hh RNAi; e–h Tc-smo RNAi; i–l Tc-ci RNAi. a Comparison of a severely affected small spherical Tc-hh RNAi cuticle and a wild-type cuticle at the same magnification. b Lateral view of a mildly affected Class I cuticle containing reduced gnathal appendages, normal legs and all abdominal segments. c Ventral view of a Class II cuticle that is similar in size and shape to more severely affected Class III cuticles but retains three pairs of thoracic appendages. Note spiracle on second thoracic segment (arrowhead). d Ventral view of a small spherical Class III cuticle with rudimentary head structures, no appendages and no segmental grooves. e Comparison of a severely affected small spherical Tc-smo RNAi cuticle and a wild-type cuticle at the same magnification. f Class I cuticle with highly reduced head structures and mouthparts but a full complement of body segments. g Class II cuticle with three pairs of legs and rudimentary head structures. Note spiracle on second thoracic segment (arrowhead). h A severely affected Class III Tc-smo RNAi cuticle phenotypically similar to the most severely affected Tc-hh RNAi cuticle. i Comparison of a severely affected small spherical Tc-ci RNAi cuticle and a wild-type cuticle at the same magnification. j Mildly affected Class I cuticle with reduced head structures, three pairs of legs and mildly fused abdominal segments. k Class II cuticles are slightly longer than intermediate Tc-hh or Tc-smo RNAi cuticles with highly fused abdominal segments. l A severely affected Class III Tc-ci RNAi spherical cuticle with three pairs of legs

The phenotypes of Tc-ci RNAi embryos are not as severe as those observed for Tc-hh or Tc-smo. The most weakly affected, Class I Tc-ci RNAi cuticles (Fig. 2j), are shorter and fatter than wild-type with severely reduced heads, but contain all thoracic and abdominal segments. The Class II Tc-ci RNAi cuticles are also shorter than wild-type with a protuberance at the anterior end and fairly normal thoracic limbs, but little to no sign of segmental grooves in the abdomen (Fig. 2k). Similar to Class III RNAi embryos of Tc-hh and Tc-smo, Class III Tc-ci RNAi embryos produced smooth unsegmented cuticles lacking heads and gnathal appendages (Fig. 2l) that are considerably smaller than wild-type cuticles (Fig. 2i). Unlike Tc-hh and Tc-smo Class III RNAi embryos, they still produced fairly normal legs (Fig. 2l). Interestingly, loss of function mutants of ci in Drosophila also produce milder limb phenotypes than do hh mutants (Methot and Basler 1999).

To understand how the segmentation process is affected by loss of Hh signaling, we followed Tc-En expression during elongation and retraction in Class III RNAi embryos (Fig. 3). In RNAi embryos for all three genes, segmental stripes of Tc-En initiate normally during germ band elongation (blue arrowheads in Fig. 3a,d and g). Tc-En expression fades as the segments matured (black arrowheads Fig. 3a,d and g), suggesting that Hh signaling is required for the maintenance of Tc-En. However, Tc-En expression in cells along the midline, presumably in the developing CNS (wild-type, Fig. 3i), is maintained in the RNAi embryos, which allowed us to follow segmentation in RNAi embryos. Tc-hh, Tc-smo, and Tc-ci RNAi embryos completed elongation more or less normally (Fig. 3a,d and g), but abnormalities became evident during retraction. The head lobes fail to mature, and there is no evidence of antennal Tc-En stripes. There is also a protuberance at the anterior end of the embryo that is likely to correspond to the anterior protuberance seen in the RNAi cuticles (Fig. 2d,h and l, and arrow in 3 h). In embryos that completed retraction, the unsegmented germbands are highly compacted, and Tc-En expression pattern is very irregular (Fig. 3c,e and h). Compared to wild-type germ bands at a similar stage, these germ bands occupy only a portion of the egg (Fig. 3j,k). In addition, loss of early Hh signaling at the ventral midline affected cell fate, as indicated by the loss of Tc-En expression here (Fig. 3b,e). Loss of Hh signal in Drosophila similarly affects En expression in midline cells (Bossing and Brand 2006). We also found that Tc-wg expression was initiated but not maintained in these embryos (data not shown), suggesting Tc-wg is a target of the Hh pathway.

En staining in wild-type and severely affected Tc-hh, Tc-smo and Tc-ci RNAi embryos during elongation and retraction. a–c Tc-hh RNAi; d–f, k Tc-smo RNAi; g, h Tc-ci RNAi; i, j wild-type. a Tc-En expression initiated normally in the posterior segments of an elongating Tc-hh RNAi germband embryo (blue arrowhead) but did not persist in older, more anterior segments (black arrowhead). b During germband retraction, patches of Tc-En expression are visible near the ventral midline, and laterally in the posterior segments. c In a highly compacted germ band with fused segments, Tc-En expression is disrupted along the ventral midline. d Expression of Tc-En in an elongating Tc-smo RNAi embryo initiated normally (blue arrowhead) but failed to persist in older, more anterior segments (black arrowhead). e During germband retraction, Tc-En is expressed in patches along the ventral midline, but has faded laterally. f In a highly compacted germ band, persists in a disrupted pattern along the ventral midline. g In an elongating Tc-ci RNAi embryo, similar to Tc-hh and Tc-smo RNAi, Tc-En initiated normally (blue arrowhead) but is not maintained (black arrowhead). h Tc-En expression at the ventral midline of a retracted germband embryo. Note the extended stomodeum (arrowhead) near the anterior end. i Tc-En expression in the CNS along the ventral midline and in the lateral ectoderm of each segment of a wild-type embryo during germband retraction. j Lateral view of a wild-type embryo inside the vitelline membrane at the end of germ band retraction. Tc-En expression persists laterally to the edge of the germband. k Ventral view of a severely affected Tc-smo RNAi embryo located near one end of the egg

hedgehog was first isolated in a screen for mutations that disrupt the Drosophila larval cuticle pattern and identified as one of the segment polarity genes with a ‘lawn of denticles’ phenotype (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus 1980). In segment polarity mutants (e.g., wg, hh, and smo), deletion of a portion of the larval epidermis in each segment is accompanied by a mirror image duplication of the remaining structures. As a result, they contain the normal number of segments, but are smaller than wild-type due to partial deletion of each segment. In our study, we found Tc-hh and Tc-smo RNAi embryos to be smaller in size than the wild-type Tribolium larva (Fig. 2a,e), which may be due to cell death, fusion, or failure of cell division in segments during germ band retraction. The few random bristles produced in severely affected RNAi cuticles do not have any definable polarity suggesting that, unlike Drosophila, loss of function of these genes in Tribolium does not appear to produce mirror image duplications or affect polarity within the segments.

Analysis of Tc-ptc and overactivation of the Hh pathway

Transcripts of Tc-ptc are first detected in a broad domain in the posterior regions of the head lobes in the embryonic rudiment encompassing the antennal segments and the stomodeum, and at the posterior end of the embryo (Fig. 4a). Broad segmental stripes of Tc-ptc appear in an anterior to posterior progression during germband elongation (Fig. 4b). Expression fades in the middle of each initial stripe resulting in two narrow Tc-ptc stripes per segment (Fig. 4c). Double staining with Tc-En and Tc-ptc indicates that in each segment, one of the narrow Tc-ptc stripes marks the anterior boundary of a segment while the other is located immediately anterior to Tc-En-expressing cells (Fig. 4c and arrowhead in inset). This pattern persists even after germ band retraction; the anterior stripe appears stronger than the posterior stripe in each segment. ptc expression during segmentation in Drosophila is similarly dynamic (Nakano et al. 1989; Hidalgo and Ingham 1990).

Analysis of Tc-ptc in Tribolium. a–c Tc-ptc expression in wild-type embryos; d–f Tc-ptc RNAi cuticles; g wild-type; h–m Tc-ptc RNAi. a Expression of Tc-ptc in three gnathal stripes, in a broad posterior region of the head lobes and in the posterior region of an early germ band embryo. b Segmental stripes appear sequentially during elongation and resolve in double stripes. c Tc-En (gold) expression in the posterior compartment abuts, but does not overlap the double Tc-ptc stripes (extent denoted by black lines) in the anterior compartment of each segment. Inset: enlarged view of Tc-ptc stripes adjacent to a stripe of Tc-En (arrowhead). d A mildly affected Class I Tc-ptc RNAi cuticle with deformed legs and head appendages. e A more severely affected Class II cuticle with enlarged misshapen legs but a normal complement of abdominal segments. f Comparison of a Class II Tc-ptc RNAi cuticle and a wild-type cuticle at the same magnification. g Expression of Tc-En (gold) and Tc-wg (purple) in a wild-type embryo during elongation. h Segmental expression of Tc-En and Tc-wg initiated fairly normally in a Tc-ptc RNAi germband. Tc-wg expression domains in the head lobes and around the proctodeum are expanded. i Expanded expression of Tc-wg in a slightly older embryo. j Ectopic stripes of Tc-En expression (blue arrowhead) in a germband undergoing retraction. k Ectopic expression of Tc-En at the ventral midline (arrowhead) in a close up of the embryo in h. l Transient grooves (arrowheads) around expanded Tc-wg expression domains in a close up of the embryo in i. m Ectopic Tc-En stripes (blue arrowhead) between each set of normal Tc-En stripes (black arrowhead) in a close up of the embryo in j. T1, first thoracic segment

As discussed above, Ptc is a negative regulator of the Hh-signaling pathway in Drosophila. Depletion of a negative regulator of the pathway would ectopically activate the pathway. To understand what happens when the Hh pathway is overactivated in Tribolium, we performed parental RNAi using two different amounts of Tc-ptc dsRNA (Table 1). The resulting cuticles (Fig. 4d,e,f) are very different from the ones described above for the other three genes. In mildly affected embryos (Class I), the head appendages are misshapen, while the legs are relatively normal (Fig. 4d). In the most severely affected embryos (Class II), all segments are present, but the head and thoracic appendages are enlarged and misshapen (Fig. 4e,f).

To understand the phenotype of the Tc-ptc RNAi embryos, we examined the expression of Tc-wg and Tc-En. In Tc-ptc-depleted embryos, segmental expression of Tc-En and Tc-wg is initiated normally (Fig. 4h), although the domains of Tc-wg expression in the head and at the posterior end of the embryo are expanded. Closer inspection revealed ectopic Tc-En expression at the ventral midline (Fig. 4k). In slightly older embryos, Tc-wg is expressed more intensely than normal in enlarged domains (Fig. 4i,l). Cells surrounding the expanded Tc-wg domains appear to be invaginating, as if beginning to form grooves. Closer inspection revealed a row of non-Tc-wg-expressing cells between the Tc-wg domain and the grooves (Fig. 4l). Tc-En is expressed in ectopic stripes that, in combination with the normal Tc-En stripes, would surround the expanded Tc-wg domains (Fig. 4j,m). In addition to the normal grooves that form posterior to the normal Tc-En stripe, ectopic grooves initiate anterior to the ectopic Tc-En stripes. Thus, overactivation of the Hh-signaling pathway in Tribolium leads to overexpression of Tc-wg, and ectopic expression of Tc-En, which results in ectopic groove formation. In Drosophila, binding of Hh to Ptc receptor relieves repression of wg and allows expression of target genes. In Drosophila ptc mutants, ectopic induction of wg and En result in the formation of extra grooves (Nakano et al. 1989), suggesting that the functional role of Ptc is highly conserved between these two species. However, unlike Drosophila, the ectopic grooves in Tribolium are transient and it appears that a late regulatory action restores the normal number of segments in this insect.

Discussion

Expression patterns suggest that the function of the Hh-signaling pathway is conserved in several developmental pathways in Tribolium.

In Tribolium, the expression patterns of the four Hh-signaling pathway components we examined are highly similar to those of their Drosophila counterparts. In both Drosophila and Tribolium, the domains of Tc-hh are very similar to those of Tc-En. However, there are some significant differences in their expression dynamics. For example, the antennal Tc-En stripes appear after the three gnathal Tc-En stripes, whereas antennal Tc-hh stripes appear before the gnathal Tc-hh stripes. Each metameric stripe of Tc-hh is laterally continuous across the width of the germband after mesoderm invagination. Later, Tc-hh expression has disappeared at the ventral midline in anterior segments, while in posterior segments the stripes are still continuous. In contrast, Tc-En expression continues in the CNS after Tc-hh expression has faded there. Tc-hh expression in the stomodeum and at the posterior end of the blastoderm embryo in the absence of Tc-En suggests that, similar to hh in Drosophila (Lee et al. 1992; Mohler and Vani 1992; Tashiro et al. 1993), Tc-hh is involved in some En-independent processes in these regions.

In both Drosophila and Tribolium, expression of segment polarity genes is initiated by pair-rule genes (recently reviewed by Damen 2007). Soon thereafter, their expression is controlled by interactions between the segment polarity genes themselves. In Drosophila, Ptc is constitutively active unless or until Hh represses Ptc activity. In the absence of Hh, unbound Ptc keeps the pathway switched off. One of the targets of the Hh pathway is ptc itself. In cells where its activity is antagonized upon binding of Hh, ptc continues to be expressed, but ptc expression disappears in cells that do not receive the signal. Thus, an initially broad domain of ptc expression resolves into two narrow stripes flanking the En expression domain. Tc-ptc expression pattern is similar: each broad stripe splits into two, such that each En stripe is bracketed by two Tc-ptc stripes, suggesting that Tc-ptc itself might also be a target of the Hh pathway in Tribolium.

The expression patterns of Hh pathway component genes are highly conserved between Drosophila and Tribolium, except for that of Tc-ci (Fig. 1l,m). In Drosophila, ci transcripts are initially expressed uniformly in the early cellular blastoderm and persist until the end of germ band elongation. At that point, ci expression is directly repressed by En in cells of the posterior compartment in each segment. In Tribolium, expression of Tc-ci is somewhat different in that there is a narrow region of two to three cells between the Tc-ci and En-expressing cells that does not express Tc-ci. In Tribolium, the absence of Tc-ci transcripts in cells just anterior to En-expressing cells might suggest the existence of an En-independent mechanism regulating Tc-ci expression. Alternatively, it is possible that Tc-ci transcripts turn over rapidly in these cells, but the expression pattern is conserved at the protein level. In Drosophila, ci is regulated post-transcriptionally. At stage 11, ci transcripts are localized throughout the anterior compartment of each segment whereas protein levels are lower at the center of each transcriptional stripe and higher in cells that bracket the En-expressing cells (Motzny and Holmgren 1995; Slusarski et al. 1995) much like what we describe here for ptc transcription in Tribolium and previously for Ptc protein levels in Drosophila. It will be interesting to see if Tc-ci is also post-transcriptionally regulated in Tribolium.

Functional analysis of Hh pathway component genes supports conserved roles in segment boundary formation.

In Drosophila, mutations in genes encoding positive regulators of the Hh pathway including hh, smo, and ci produce smaller than wild-type embryos with asegmental phenotypes (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus 1980). In Tribolium, Tc-hh, and Tc-smo RNAi embryonic phenotypes are nearly identical; both produce highly compacted spherical cuticles with no evidence of appendages or segmental grooves. The most severe Tc-ci RNAi phenotypes are not as severe as those of Tc-hh or Tc-smo RNAi. Interestingly, the ci94 allele in Drosophila is a null allele (Slusarski et al. 1995; Methot and Basler 1999) and these mutant embryos differ considerably from hh mutants. hh mutants are much shorter in length and have a continuous ‘lawn of denticles’ phenotype whereas ci94 mutants are almost normal in size and have alternating naked cuticle and denticle belts on the ventral surface. Target genes of hh are partially derepressed in the absence of ci, producing a ci phenotype that is milder than that of hh (Methot and Basler 2001). An analogous situation has been described for the Wingless signaling pathway in Drosophila where derepression of target genes in the absence of pangolin results in a milder segment polarity phenotype compared to that of wg null mutants (Cavallo et al. 1998; Waltzer and Bienz 1998). In hh and smo mutants, only the repressor function of ci remains, producing the catastrophic phenotype. In contrast, loss of both the activating and repressor forms results in the milder phenotype seen in ci null mutants. In Tribolium, the most severe Tc-ci RNAi phenotype is milder than the most severe Tc-hh RNAi phenotype, suggesting similar regulation of the Hh pathway in the beetle.

In Drosophila, loss of Wg or Hh-signaling results in larvae that are smaller than wild-type due, at least in part, to epidermal cell death during and after germband retraction (Martinez-Arias and Lawrence 1985) or a combination of transformation and cell death (Klingensmith et al. 1989). In Tribolium, hh, smo, and ci RNAi individuals are greatly reduced in size compared to the wild-type (Fig. 2). These embryos go through the events of early embryogenesis normally, producing the full complement of segments and initiating Tc-En and Tc-wg expression. Tc-En and Tc-wg expression fade and the segmental remnants become highly compacted along the anterior–posterior axis during retraction. Tribolium embryos lacking Tc-wg also elongate normally but fail to maintain En expression and form shorter than wild-type embryos during retraction (Ober and Jockusch 2006). While it is likely that cell proliferation and programmed cell death both contribute to shaping the embryo in Tribolium, during normal development cells divide randomly throughout the elongating germ band (Brown et al. 1994); organized patterns of cell division or cell death have not been reported. Similarly, it is likely that excessive cell death or the lack of cell proliferation contributes to the severely compacted terminal phenotype of Tc-hh, Tc-smo or Tc-ci RNAi embryos, but closer examination will be required to determine if this is so.

In Drosophila ptc mutants, deletion of the midregion of each segment is accompanied by a mirror image duplication of the remaining denticles (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus 1980). In contrast, Tribolium Tc-ptc RNAi embryos, which also display the correct number of segments, are characterized by distended gnathal and thoracic appendages. Although there are some random bristles, we could not identify any noteworthy difference in the polarity of these bristles that could be attributed to a characteristic loss of function phenotype for genes belonging to this class. This suggests that unlike Drosophila, the loss of segment polarity gene function in Tribolium does not result in any morphologically identifiable polarity defect in the cuticle.

In the absence of ptc in Drosophila (DiNardo et al. 1988) and Tribolium, En expression is established properly; but later, de novo En stripes appear between the normal stripes. Ectopic expression of En in Drosophila is not due to regulation of ptc by pair-rule factors (DiNardo et al. 1988). In the absence of ptc, the wg expression domain broadens anteriorly. Expanded wg expression induces ectopic En stripes, which cause ectopic groove formation, suggesting that the principal function of Ptc is to repress wg. Similar expression of Tc-ptc in Tribolium, considered with the expanded Tc-wg domains that are surrounded by ectopic Tc-En-expressing cells and the ectopic grooves transiently formed in Tc-ptc RNAi embryos suggest that the role of Tc-ptc is likely to be functionally conserved between Drosophila and Tribolium. However, in Tc-ptc RNAi embryos, ectopic Tc-En is also detected along the ventral midline, a phenotype that has not been described for Drosophila ptc mutants. hh RNAi has been attempted in the orthopteran Gryllus bimaculatus (Miyawaki et al. 2004). Unfortunately, this organism seems to be resistant to hh dsRNA. In the RNAi embryos, the level of hh is not reduced. The embryos develop normally and hatched larvae show no cuticular defects. Lack of ptc analysis in other insects makes it difficult to speculate as to whether this novel expression of Tc-En along the ventral midline is specific to Tribolium, or a general feature related to short germ development. Finally, although ectopic grooves appear to form around the expanded Tc-wg domains, they are not detected in the terminal cuticles, implying that events late in embryogenesis restore the normal number of segmental grooves.

Conservation of the hh–wg–en gene circuit in short germ segmentation

Several lines of evidence suggest that the segment polarity gene circuit, in which the expression of the hh, wg, and en genes are dependent upon one another in the long germ mode of segmentation elucidated in Drosophila, is conserved in the short germ mode of segmentation found in Tribolium. As in Drosophila, in the absence of smo, hh, ci (this paper), or wg (Ober and Jockusch 2006) in Tribolium, En expression is not maintained. In addition, Tc-wg mRNA fails to persist in Tc-hh, Tc-smo and Tc-ci RNAi embryos (data not shown). Furthermore, expression patterns and RNAi phenotypes of the Hh pathway components we examined (Tc-hh, Tc-smo, Tc-ci, and Tc-ptc) suggest that the regulation of the Hh pathway is also conserved. Segment polarity genes, which function last in the segmentation gene hierarchy, are expressed in segmental fields that have been predefined by genes at higher levels (gap and pair rule). Conservation of the segment polarity gene circuit in Tribolium suggests that that segment polarity genes form a robust regulatory module in the short germ mode of segmentation in this beetle and their expression patterns in numerous insects and chilicerates suggest that this module is likely to be conserved among the Insecta, and perhaps the Arthropoda.

While the expression patterns of segment polarity orthologs are highly conserved, the expression patterns of pair-rule gene orthologs vary greatly among insects and other arthropods (recently reviewed in Tautz 2004; Peel et al. 2005; Damen 2007). Functional analysis in Tribolium indicates that interactions among pair-rule gene homologs differ from those of their Drosophila counterparts (Choe et al. 2006) and that some secondary pair-rule genes function in opposite parasegmental registers in Drosophila and Tribolium (Choe and Brown 2006). These findings suggest that the inputs from pair-rule genes to the segment polarity gene module are likely to be quite different in each of these insects. Functional analysis of how pair-rule genes regulate the alternating expression of en and wg in Tribolium will provide insight into these differences, which will ultimately help us understand the evolution of genetic regulatory networks. Interestingly, the segment polarity gene module seems to be resilient enough to withstand such evolutionary changes in input from the pair-rule gene module.

References

Alcedo J, Ayzenzon M, Von Ohlen T, Noll M, Hooper JE (1996) The Drosophila smoothened gene encodes a seven-pass membrane protein, a putative receptor for the hedgehog signal. Cell 86:221–232

Alexandre C, Jacinto A, Ingham PW (1996) Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev 10:2003–2013

Alves G, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Tricoire H, Brissard-Zahraoui J, Lamour-Isnard C, Busson D (1998) Modulation of Hedgehog target gene expression by the Fused serine-threonine kinase in wing imaginal discs. Mech Dev 78:17–31

Angelini DR, Kaufman TC (2005) Functional analyses in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus (Hemiptera) support a role for Wnt signaling in body segmentation but not appendage development. Dev Biol 283:409–423

Aza-Blanc P, Ramirez-Weber FA, Laget MP, Schwartz C, Kornberg TB (1997) Proteolysis that is inhibited by hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell 89:1043–1053

Beeman RW, Stuart JJ, Haas MS, Denell RE (1989) Genetic analysis of the homeotic gene complex (HOM-C) in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol 133:196–209

Beye M, Hartel S, Hagen A, Hasselmann M, Omholt SW (2002) Specific developmental gene silencing in the honey bee using a homeobox motif. Insect Mol Biol 11:527–532

Bossing T, Brand AH (2006) Determination of cell fate along the anteroposterior axis of the Drosophila ventral midline. Development 133:1001–1012

Brown SJ, Patel NH, Denell RE (1994) Embryonic expression of the single Tribolium engrailed homolog. Dev Genet 15:7–18

Bucher G, Scholten J, Klingler M (2002) Parental RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera). Curr Biol 12:R85–86

Cavallo RA, Cox RT, Moline MM, Roose J, Polevoy GA, Clevers H, Peifer M, Bejsovec A (1998) Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 395:604–608

Chen Y, Struhl G (1996) Dual roles for patched in sequestering and transducing Hedgehog. Cell 87:553–563

Choe CP, Brown SJ (2006) Evolutionary flexibility of pair-rule patterning revealed by functional analysis of secondary pair-rule genes, paired and sloppy-paired in the short germ insect, Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol 302(1):281–294

Choe CP, Miller SC, Brown SJ (2006) A pair-rule gene circuit defines segments sequentially in the short-germ insect Tribolium castaneum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:6560–6564

Damen WG (2002) Parasegmental organization of the spider embryo implies that the parasegment is an evolutionary conserved entity in arthropod embryogenesis. Development 129:1239–1250

Damen WG (2007) Evolutionary conservation and divergence of the segmentation process in arthropods. Dev Dyn 236:1379–1391

Dhawan S, Gopinathan KP (2002) Molecular cloning and expression pattern of a Cubitus interruptus homologue from the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori. Mech Dev 118:203–207

Dhawan S, Gopinathan KP (2003) Spatio-temporal expression of wnt-1 during embryonic-, wing- and silkgland development in Bombyx mori. Gene Expr Patterns 3:559–570

DiNardo S, O'Farrell PH (1987) Establishment and refinement of segmental pattern in the Drosophila embryo: spatial control of engrailed expression by pair-rule genes. Genes Dev 1:1212–1225

DiNardo S, Sher E, Heemskerk-Jongens J, Kassis JA, O'Farrell PH (1988) Two-tiered regulation of spatially patterned engrailed gene expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Nature 332:604–609

Dominguez M, Brunner M, Hafen E, Basler K (1996) Sending and receiving the hedgehog signal: control by the Drosophila Gli protein Cubitus interruptus. Science 272:1621–1625

Forbes AJ, Nakano Y, Taylor AM, Ingham PW (1993) Genetic analysis of hedgehog signalling in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Suppl:115–124

Grbic M, Nagy LM, Carroll SB, Strand M (1996) Polyembryonic development: insect pattern formation in a cellularized environment. Development 122:795–804

Hepker J, Wang QT, Motzny CK, Holmgren R, Orenic TV (1997) Drosophila cubitus interruptus forms a negative feedback loop with patched and regulates expression of Hedgehog target genes. Development 124:549–558

Hidalgo A, Ingham P (1990) Cell patterning in the Drosophila segment: spatial regulation of the segment polarity gene patched. Development 110:291–301

Hooper JE, Scott MP (1989) The Drosophila patched gene encodes a putative membrane protein required for segmental patterning. Cell 59:751–765

Howard K, Ingham P, Rushlow C (1988) Region-specific alleles of the Drosophila segmentation gene hairy. Genes Dev 2:1037–1046

Huangfu D, Anderson KV (2006) Signaling from Smo to Ci/Gli: conservation and divergence of Hedgehog pathways from Drosophila to vertebrates. Development 133:3–14

Ingham PW, Baker NE, Martinez-Arias A (1988) Regulation of segment polarity genes in the Drosophila blastoderm by fushi tarazu and even skipped. Nature 331:73–75

Ingham PW, Hidalgo A (1993) Regulation of wingless transcription in the Drosophila embryo. Development 117:283–291

Ingham PW, McMahon AP (2001) Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev 15:3059–3087

Ingham PW, Taylor AM, Nakano Y (1991) Role of the Drosophila patched gene in positional signalling. Nature 353:184–187

Janssen R, Prpic NM, Damen WG (2004) Gene expression suggests decoupled dorsal and ventral segmentation in the millipede Glomeris marginata (Myriapoda: Diplopoda). Dev Biol 268:89–104

Klingensmith J, Noll E, Perrimon N (1989) The segment polarity phenotype of Drosophila involves differential tendencies toward transformation and cell death. Dev Biol 134:130–145

Kraft R, Jackle H (1994) Drosophila mode of metamerization in the embryogenesis of the lepidopteran insect Manduca sexta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:6634–6638

Lee JJ, von Kessler DP, Parks S, Beachy PA (1992) Secretion and localized transcription suggest a role in positional signaling for products of the segmentation gene hedgehog. Cell 71:33–50

Martinez-Arias A, Lawrence PA (1985) Parasegments and compartments in the Drosophila embryo. Nature 313:639–642

Mellenthin K, Fahmy K, Ali RA, Hunding A, Da Rocha S, Baumgartner S (2006) Wingless signaling in a large insect, the blowfly Lucilia sericata: a beautiful example of evolutionary developmental biology. Dev Dyn 235:347–360

Methot N, Basler K (1999) Hedgehog controls limb development by regulating the activities of distinct transcriptional activator and repressor forms of Cubitus interruptus. Cell 96:819–831

Methot N, Basler K (2001) An absolute requirement for Cubitus interruptus in Hedgehog signaling. Development 128:733–742

Miyawaki K, Mito T, Sarashina I, Zhang H, Shinmyo Y, Ohuchi H, Noji S (2004) Involvement of Wingless/Armadillo signaling in the posterior sequential segmentation in the cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus (Orthoptera), as revealed by RNAi analysis. Mech Dev 121:119–130

Mohler J, Vani K (1992) Molecular organization and embryonic expression of the hedgehog gene involved in cell–cell communication in segmental patterning of Drosophila. Development 115:957–971

Monnier V, Dussillol F, Alves G, Lamour-Isnard C, Plessis A (1998) Suppressor of fused links fused and Cubitus interruptus on the hedgehog signalling pathway. Curr Biol 8:583–586

Motzny CK, Holmgren R (1995) The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mech Dev 52:137–150

Nagaso H, Murata T, Day N, Yokoyama KK (2001) Simultaneous detection of RNA and protein by in situ hybridization and immunological staining. J Histochem Cytochem 49:1177–1182

Nagy LM, Carroll S (1994) Conservation of wingless patterning functions in the short-germ embryos of Tribolium castaneum. Nature 367:460–463

Nakano Y, Guerrero I, Hidalgo A, Taylor A, Whittle JR, Ingham PW (1989) A protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains encoded by the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched. Nature 341:508–513

Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E (1980) Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 287:795–801

Ober KA, Jockusch EL (2006) The roles of wingless and decapentaplegic in axis and appendage development in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol 294:391–405

Oppenheimer DI, MacNicol AM, Patel NH (1999) Functional conservation of the wingless-engrailed interaction as shown by a widely applicable baculovirus misexpression system. Curr Biol 9:1288–1296

Orenic TV, Slusarski DC, Kroll KL, Holmgren RA (1990) Cloning and characterization of the segment polarity gene cubitus interruptus dominant of Drosophila. Genes Dev 4:1053–1067

Patel NH, Kornberg TB, Goodman CS (1989) Expression of engrailed during segmentation in grasshopper and crayfish. Development 107:201–212

Peel AD, Chipman AD, Akam M (2005) Arthropod segmentation: beyond the Drosophila paradigm. Nat Rev Genet 6:905–916

Peterson MD, Popadic A, Kaufman TC (1998) The expression of two engrailed-related genes in an apterygote insect and a phylogenetic analysis of insect engrailed-related genes. Dev Genes Evol 208:547–557

Sander K (1997) Pattern formation in insect embryogenesis: the evolution of concepts and mechanisms. Int J of Insect Morphol Embryol 25:349–367

Simonnet F, Deutsch J, Queinnec E (2004) hedgehog is a segment polarity gene in a crustacean and a chelicerate. Dev Genes Evol 214:537–545

Sisson JC, Ho KS, Suyama K, Scott MP (1997) Costal2, a novel kinesin-related protein in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell 90:235–245

Slusarski DC, Motzny CK, Holmgren R (1995) Mutations that alter the timing and pattern of cubitus interruptus gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 139:229–240

Tabata T, Eaton S, Kornberg TB (1992) The Drosophila hedgehog gene is expressed specifically in posterior compartment cells and is a target of engrailed regulation. Genes Dev 6:2635–2645

Tashiro S, Michiue T, Higashijima S, Zenno S, Ishimaru S, Takahashi F, Orihara M, Kojima T, Saigo K (1993) Structure and expression of hedgehog, a Drosophila segment-polarity gene required for cell–cell communication. Gene 124:183–189

Tautz D (2004) Segmentation. Dev Cell 7:301–312

Tautz D, Pfeifle C (1989) A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma 98:81–85

Tomoyasu Y, Miller S, Tomita S, Schoppmeier M, Grossmann D, Bucher D (2008) Exploring systemic RNA interference in insects: a genome-wide survey for RNAi genes in Tribolium. Genome Biology 9:R10

van den Heuvel M, Ingham PW (1996) Smoothened encodes a receptor-like serpentine protein required for hedgehog signalling. Nature 382:547–551

Waltzer L, Bienz M (1998) Drosophila CBP represses the transcription factor TCF to antagonize Wingless signalling. Nature 395:521–525

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yoshinori Tomoyasu for the cDNA clones of Tribolium hedgehog, cubitus interruptus, smoothened, and patched. We thank Cassondra Michelle Gordon and Canda Harvey for expert technical assistance and members of the lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NSF grant IOB0321882, NIH grant HD29594 and grants from the TC Johnson Center for Basic Cancer Research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by S. Roth

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Farzana, L., Brown, S.J. Hedgehog signaling pathway function conserved in Tribolium segmentation. Dev Genes Evol 218, 181–192 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-008-0207-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-008-0207-2