Abstract

Background

In a previous report (La et al., Proteins, 2005), we have demonstrated that the identification of phylogenetic motifs, protein sequence fragments conserving the overall familial phylogeny, represent a promising approach for sequence/function annotation. Across a structurally and functionally heterogeneous dataset, phylogenetic motifs have been demonstrated to correspond to a wide variety of functional site archetypes, including those defined by surface loops, active site clefts, and less exposed regions. However, in our original demonstration of the technique, phylogenetic motif identification is dependent upon a manually determined similarity threshold, prohibiting large-scale application of the technique.

Results

In this report, we present an algorithmic approach that determines thresholds without human subjectivity. The approach relies on significant raw data preprocessing to improve signal detection. Subsequently, Partition Around Medoids Clustering (PAMC) of the similarity scores assesses sequence fragments where functional annotation remains in question. The accuracy of the approach is confirmed through comparisons to our previous (manual) results and structural analyses. Triosephosphate isomerase and arginyl-tRNA synthetase are discussed as exemplar cases. A quantitative functional site prediction assessment algorithm indicates that the phylogenetic motif predictions, which require sequence information only, are nearly as good as those from evolutionary trace methods that do incorporate structure.

Conclusion

The automated threshold detection algorithm has been incorporated into MINER, our web-based phylogenetic motif identification server. MINER is freely available on the web at http://www.pmap.csupomona.edu/MINER/. Pre-calculated functional site predictions of the COG database and an implementation of the threshold detection algorithm, in the R statistical language, can also be accessed at the website.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Due to the exponential growth of genomic and protein sequence data, development of automated strategies for large scale functional site identification is an important post-genomic challenge. Many recent efforts predict functional sites from sequence alone. Strong candidates for functional sites include individual highly conserved positions within a sequence alignment and highly conserved sequence motifs [1–5]. Although attractive due to their relative simplicity, conservation-based approaches frequently result in too many false positives to be satisfactory [3]. Further, sequence regions with significant variability can also be functionally important [6], especially when their composition may define sub-family functional specificity. The Evolutionary Trace (ET) procedure [7], and similar approaches [6, 8, 9], address this problem by using evolutionary information to identify subfamily conserved, yet overall variable, positions. It has been demonstrated that the ET methods identify statistically significant structural clusters [10] and has subsequently been established in large scale analyses [11].

Recently, we demonstrated that sequence fragments conserving the overall phylogeny, termed phylogenetic motifs (PMs), are very likely to correspond to protein functional sites [12]. We briefly highlight the key results of our previous report here (see Implementation for a technical description of the approach). Despite little overall sequence proximity, PMs are structurally clustered around a wide variety of protein functional regions, including sites defined by surface loops, active site clefts, substrate binding epitopes, and protein-protein interfaces. Ostensibly, PMs identify sequence clusters of ET positions, and, as expected, the results of the two approaches are similar. However, compared to raw ET predictions, PMs seem to be more structurally focused on active site regions. Lastly, we have demonstrated appreciable tree significance of the fragment windows, especially in PM regions, using bootstrap analysis.

In a recent review, Jones and Thornton [13] classify protein functional site prediction strategies into one of two groups: (1) those based on sequence conservation and (2) those based on "feature" (i.e. phylogenetic) conservation. Congruence between phylogenetic and traditional motifs has been clearly established [12]. As a consequence, PMs bridge the two normally disparate groups. For example, in the case of triosephosphate isomerase, all seven traditional motifs are also identified as PMs, including the PROSITE [14] definition of the family. However, due to the large number of clades within some families (e.g. cytochrome P450) there are instances when PM sequences are not overall conserved. This point is in enticing because it suggests that PMs can sometimes functionally annotate regions that traditional methods would ignore. Furthermore, it has been reported [12] that traditional motifs not conserving phylogeny are less likely to be structurally clustered around known functional sites.

PMs are identified using a sliding sequence window algorithm that exhaustively compares the phylogenetic similarity of each fragment window to the complete familial tree. Phylogenetic similarity z-scores (PSZs), which are defined below, quantify the similarity between the window and familial tree. (Smaller PSZs indicate greater phylogenetic similarity.) In our current approach, all overlapping windows scoring past some PSZ threshold are identified as a PM. The PSZ threshold is manually adjusted to define what constitutes a "hit". Automated threshold determination is a difficult problem because no single threshold value is sufficient for every instance. Each protein family requires a unique value to correctly identify a signal (a PM window) from noise. In our previous work, we manually set threshold values where PSZs strongly deviate from all other values. Structural analyses indicate that ideal PSZ threshold ranges between -1.5 and -2.0. In other words, the ideal phylogenetic similarity cutoff for accurate functional site predictions generally falls between 1.5 and 2 standard deviations away from the mean of the PSZ distribution.

In this report, we describe an automated algorithm for determining proper PSZ thresholds. Structural analyses and comparisons to our previous manual thresholds indicate that the approach retains functional site prediction accuracy. The method utilizes significant raw data preprocessing that eliminates unnecessary (redundant) data points. Subsequently, the robust Partition Around Medoids Clustering (PAMC) algorithm is employed to automatically determine the appropriate PSZ thresholds. The implemented approach is computationally efficient and demonstrated to be suitable for large, heterogeneous datasets, which remains a difficult bioinformatic problem [15].

Implementation

Phylogenetic motif identification

During PM identification, we mask the multiple sequence alignment by purging all highly (more than 50%) gapped positions. The masked alignment is parsed into a series of sequence fragment windows of fixed width. In this report, a window width of five, which has previously been shown to be most sensitive for identifying functional sites [12], is used throughout. Except for the copper, zinc superoxide dismutase and myoglobin families, which use the same datasets as before [12], all sequences are taken from the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) database [16]. Only COGs with more than 25 sequences are investigated to ensure proper and significant tree construction. Pairwise tree similarity is calculated using a modified partition metric algorithm [17], which counts the number topological differences between the fragment window and familial trees. Thus, smaller partition metric scores correspond to greater tree similarity. Phylogenetic similarity is measured using z-scores calculated from the raw partition metric distribution. Although not the best alignment method for distantly related sequences, ClustalW (v1.83) alignments are used throughout [18]. Given the similarity within the COG families, ClustalW alignments are satisfactory.

Phylogenetic trees are constructed using the neighbor-joining implementation within ClustalW. Neighbor-joining is a distance-based approach for constructing phylogenetic trees commonly used for bootstrap analysis that requires massive tree sampling [19]. Similarly, due to the large number of window trees required here, the algorithmic efficiency of distance-based methods is necessary. For example, in the medium-sized triosephosphate isomerase protein family, over 250 trees must be calculated. Furthermore, as Kuhner and Felsenstein point out [20], distance-based approaches actually outperform maximum-likelihood methods when applied to short sequences. MINER, our web-based implementation of the PM identification algorithm, is available online at http://www.pmap.csupomona.edu/MINER/[21]. A standalone version of MINER, implemented in PERL, is freely available to the Academic community upon request.

Raw data preprocessing

Empirically, our manual assessment of functional site prediction accuracy indicates that all PSZs below χ ≈ -2 should be identified as PMs, whereas PSZ's above -1 should never be considered. In the subsequent clustering step, only scores between -1 and χ are used to define the PSZ. This simplification is taken because the objective of this work is to automatically classify windows whose determination remain in question. The significance of the PSZs outside this range is known a priori, thus they can be eliminated from further consideration. Clustering of the data points between -1 and χ (termed the "gap") was originally expected to automatically determine the appropriate PSZ threshold. However, several different clustering techniques (hierarchical, k-means, PAMC, and expectation-maximization) have failed to provide satisfactory results.

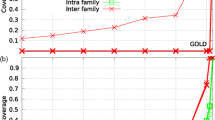

In order to accentuate differences within the PSZ distribution, and thus simplifying the clustering problem, the following preprocessing procedure is employed. As stated above, all overlapping windows scoring past some predetermined threshold are defined as PMs. We use the same rationale in detecting PSZ thresholds. The process begins by identifying all overlapping windows scoring past -1. For the purpose of threshold detection only, we "sharpen" these regions by selecting the lowest window score as a reference; all other scores are eliminated. This process has the effect of reducing the number of contiguous and related PSZ scores (corresponding to overlapping windows) into a single value (see Figure 1). After accentuating the high phylogenetic similarity regions, PAMC can robustly identify the ideal PSZ threshold. Several different upper bounds have been considered, but our empirical results indicate that -1 is best.

Partitioning Around Medoids Clustering (PAMC) is used to partition PSZs between -1.0 and χ = -2.0 into two groups (signal and noise clusters). The results from the (A) raw and (B) sharpened PSZ datasets are shown. Red indicated sharpened data points. We demonstrate two common scenarios (left) triosephosphate isomerase and (right) arginyl-tRNA synthetase. In all cases, it is clear that sharpening the PSZ dataset allows one to more easily discern the number of distinctive potential signals under the partition boundary (gap) in question. (C) The effect of different sharpening ranges is demonstrated. PSZ ranges tested include -1.0 to -2.0 (red), -2.5 (dark orange), and -3.0 (light orange). In the case of triosephosphate isomerase the first two ranges give identical results. The ideal threshold is found to be -1.65 and -2.20 for triosephosphate isomerase and arginyl-tRNA synthetase, respectively.

Automated PSZ threshold determination

PAMC is a partitioning algorithm based on the k-means approach of clustering [22]. In k-means clustering [23], the center of a cluster is represented by its arithmetic average. In PAMC, each cluster is represented by the median value, making PAMC a k-medoids approach. The basic concept of PAMC is to partition a dataset containing a number of points into k number clusters. PAMC starts from an initial random set of medoids and iteratively swaps medoids with non-medoids to evaluate if the total distances between clusters are improved. PAMC is more effective and robust than k-means for small datasets because medians are less biased by outliers deviating from the mean. Our PSZ dataset is small, especially after preprocessing, making PAMC an appropriate clustering choice. In addition, because the goal is to separate signals (cluster one) from noise (cluster two), k-based approaches are ideal. The preprocessed gap is differentiated into k = 2 number of groups. Clustering is performed by the PAMC implementation within the cluster package of the R statistical language [24]. The PAM algorithm implemented in R simply uses the Euclidean measure by default and the Manhattan as a defined alternative. We use the Euclidean measure throughout.

In determining the ideal PSZ threshold value, the number of data points in the signal cluster is counted. If the signal cluster contains five or less data points, the threshold is set to the most accommodating (least negative) value in that cluster. However, an algorithmic override that defines the PSZ threshold at the first (rank ordered) PSZ above χ if any of the following three situations occur: (1) if the signal cluster contains more than five data points, (2) if less than three points reside in the gap – it does not make sense to cluster so few data points into two groups, or (3) no PSZs lower than -2 are present within the distribution. The algorithmic override prevents normalizes the number of putative functional sites, preventing both too many and too few predictions. Empirical results investigating the accuracy of the method's predictions vis-à-vis structure indicate that the algorithmic override maximizes accuracy. For example, in examples where the override reduces the number of predictions, frequently the excluded sites are structurally removed from the active site region. The ideal value of χ is established in the next section.

Quantitative assessment of functional site predictions

The accuracy of the functional site predictions herein is quantitatively determined using the method put forth by Aloy et al. [25]. In the scheme, a known functional site sphere is defined by the location of SITE and ACTSITE records within a PDB file. In line with our previous report [12], we also include residues directly interacting with substrates and catalytically important metal ions, which are identified using LIGPLOT [26]. Prediction spheres are similarly constructed for each PM. The accuracy of each PM prediction is based on the relative location of the known functional site and prediction spheres. If the prediction sphere is completely engulfed within the known functional site sphere, then the prediction is deemed correct. If the two spheres partially overlap, then the prediction provides useful information. And, if there is no overlap between the two spheres, then the prediction is wrong. In the case of the known functional site, the sphere is centered on the geometric center of the CB atoms (CA for glycine) of all functional residues. Similarly, the PM sphere is centered on the geometric center of the corresponding CB atoms (CA for glycine). In both cases, the sphere is made just large enough to include all functional or PM residues.

Results and discussion

Establishing algorithm parameters

As described below, the automatic threshold determination problem is simplified when considering only the most extreme of several contiguous and related, PSZ values. We call this process data sharpening. As a consequence, identification of the true phylogenetic signals is greatly simplified. In contrast, contiguous windows with similar values are the result of a single PM, making it difficult to properly count the number of true signals in an unsharpened dataset. Because PMs are defined as all overlapping windows scoring past the PSZ threshold, reducing the complexity of the problem to be in line with the number of PMs, versus number of windows, makes intuitive sense. For example, if two PMs are considered, the first consisting of three overlapping windows and the second with five, only two unique signals, compared to the eight constituent windows, are considered. Comparisons of sharpened and unsharpened datasets are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Thresholds are determined by first evaluating the optimal range using the PAM clustering algorithm. Determining whether a threshold can be placed within the range of -1.0 and -2.0 allows thresholds to sensitively accommodate more functional sites, widening this range results in more stringent thresholds. Figure 1C illustrates different thresholds determined when considering three different PSZ ranges. By broadening the range of the triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) dataset, two distinct thresholds are found. Ranges of {-1.0: -2.0} and {-1.0: -2.5} identify the same threshold (PSZ = -1.65). However, expanding the gap to {-1.0: -3.0} results in a significantly more stringent threshold (PSZ = -2.86). The former PSZ threshold is more similar to our manual determination of PSZ = -1.5 [12].

Similarly, the arginyl-tRNA synthetase family is evaluated using the same three gap ranges. Like TIM, the determined threshold becomes more stringent as the gap broadens. However, the three gap ranges result in three distinct PSZ threshold values. The arginyl-tRNA synthetase example is noteworthy because the determined threshold in all three instances is algorithmically set below χ. This occurs because too many points exist in the PAM identified signal cluster. Since we assume functional sites cover only a fraction of the protein sequence space, when the signal cluster is larger than five, it is disregarded and the PSZ threshold is set at the first (rank ordered) PSZ past χ.

Comparison of all three gap ranges on the determined PSZ threshold for the 15 functionally and structurally diverse proteins used previously [12] is partially used to determine the ideal gap range. In all cases, the functional significance of the manually determined threshold has been demonstrated using structural analysis. Additionally, the exact catalytic role of many of the identified PMs (especially TIM [27], enolase [28], inorganic pyrophosphatase [29], copper, zince superoxide dismutase [30], and TATA-box binding protein [31]) has also been delineated. For example, eight PMs are identified in the case of TIM, which cover all eight LIGPLOT [26] identified electrostatic interactions between enzyme and substrate. Furthermore, the flexible "lid" region, which covers the active site during catalysis [32–35], is also identified as a functional site. We have also recently demonstrated that PMs within TIM (and two other TIM-barrel families) also correspond to evolutionarily conserved electrostatic networks that fine-tune the pKa values of catalytic residues [36].

The frequency of threshold values (displayed as kernel density estimates) determined using the three different gap ranges is illustrated in Figure 2 for the entire COG database [16]. Of the three PSZ ranges tested, the threshold distribution resulting from the narrowest range is most similar to the distribution of our structurally verified dataset. Using a two-sample t-test, the statistical significance between the PSZ threshold distributions can be assessed. The t-test results (t = -0.41, p = 0.69) indicate that the manual and {-1.0: -2.0} distributions are not statistically different. However, when evaluating the manual threshold distribution with the other two gap ranges, (t = -6.08, p = 2.14 × 10-05) and (t = -9.49, p = 6.85 × 10-08) for {-1.0: -2.5} and {-1.0: -3.0}, respectively, we find that the differences are highly significant. Furthermore, the distribution of thresholds from the {-1.0: -2.0} show the most frequent PSZ thresholds are set around -1.5 and -2.0, which is in line with our original conclusions. A gap range of {-1.0: -2.0} is used throughout the remainder of this report. Table 1 compares the manually and automatically determined PSZ thresholds.

The frequencies of the three different PSZ thresholds are found on 1571 protein families (all COGs with more than 25 sequences). The normalized frequencies are represented as kernel density estimates. All optimal ranges used consist of two maximum densities from -1.0 to -3.0 (PSZ = -3.04 and -1.82), from -1.0 to -2.5 (PSZ = -2.60 and -1.74), and from -1.0 to -2.0 (PSZ = -2.01 and -1.58). Kernel densities from fifteen manually set thresholds that have been structurally verified also contain two maximum densities (PSZ = -2.12 and -1.53). Of the three ranges tested, the {-1.0: -2.0} gap is the only one that is statistically similar to the structurally verified results. The coloring of the three ranges is the same as in Figure 2C.

Functional annotation of the COG database

Using the procedure established above, we exhaustively functionally annotated the most recent update [16] of the COG database. After parsing out COGs with less than 25 sequences, our dataset is composed of 1571 protein families. The number of PMs identified resembles a bell curve centered on 6.1 motifs per COG (Figure 3A). The standard deviation is 2.9. 24 PMs, the most of any COG investigated, are identified within the cobalamin biosynthesis protein family. Due to the extreme size of this protein, the number of identified PMs is within the expected range – the cobalamin biosynthesis protein family alignment is the second longest in our dataset. Consistent with our earlier qualitative observations [36], Figure 4 reveals a roughly linear correlation between alignment length and the number of phylogenetic motifs identified per COG.

(A) Histogram tabulating the number of phylogenetic motifs per COG. (B) Histogram tabulating phylogenetic motif width (note logarithmic scale). The theoretical lower bound on motif width (five, which equals one fragment window) occurs 51% of the time. The {-1.0: -2.0} gap range is used in both cases.

Number of phylogenetic motifs per COG, using the {-1.0: -2.0} gap range, is plotted against alignment length. As expected, there is a direct correlation between the two quantities. At least one phylogenetic motif is identified in each COG. Conversely, in large COGs 10+ phylogenetic motifs are routinely identified.

In total, 9558 PMs are identified. Compared to the number of PMs per COG, there is much more heterogeneity within the motif width distribution (Figure 3B). The theoretical lower bound on PM width is five (one fragment window); whereas there is no limit on their maximum size. A motif width of five is by far the most common, occurring 51% of the time. The maximum width observed, which occurs in the methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein family, is 42 (occurring once). The large motif corresponds to the chemotaxis transduction 2 domain. As a stark contrast, only one other PM (width = 5) is identified within this family. The second, and much smaller, motif coincides with the PROSITE [14] definition (R-T-E- [EQ]-Q) of the family. The [EQ] position is a site of reversible methylation.

The large-scale nature of this analysis provides an opportunity to assess the dependence of several factors on the automatically determined PSZ thresholds. Correlations between the determined PSZ thresholds and number of PMs identified, number of sequences in the dataset, and alignment length are calculated (see Table 2). As discussed, a roughly linear (R = 0.68) correlation between number of PMs identified and alignment length is identified (Figure 4). However, no other strong correlations are identified between any of the probed characteristics. While more-or-less uninteresting, this result is actually encouraging because it indicates that PMs, in addition to being accurate, represent a robust functional site prediction algorithm suitable for large, heterogeneous datasets.

Molecular examples

Clustering of the three different TIM gap ranges uncovers two putative PSZ thresholds (see Figure 1C). We demonstrate above that the narrowest gap range (and as a consequence, the most lenient PSZ threshold) to be appropriate. In this case, however, both the {-1.0: -2.0} and the {-1.0: -2.5} gap ranges set the threshold at -1.83. The determined threshold sensitively accommodates the complete substrate binding epitope, including all eight enzyme-substrate electrostatic interactions. However, the {-1.0: -3.0} range identifies a more stringent threshold (-2.75), which misses one enzyme-substrate salt bridge and one hydrogen bond. Several other less drastic differences also occur. A structural analysis of these automatically set thresholds is shown in Figure 5. Despite the differences between the two thresholds, both identify PMs that correspond to the PROSITE [14] definition of the family, the flexible "lid", and most of the enzyme-substrate contacts. In both cases, all identified PMs are structurally clustered at the C-terminal end of the barrel.

Triosephosphate isomerase phylogenetic motifs identified at the two different PSZ thresholds. Colored spheres indicate phylogenetic motif α-carbons identified past the (A) -1.83 and (B) -2.75 thresholds, which correspond to gap ranges of {-1.0: -2.0} and {-1.0, -3.0}, respectively. The {-1.0: -2.5} gap range identifies the same threshold as (A). The substrate analog is colored white. Making the threshold more stringent fails to identify residues (the red phylogenetic motif) involved in two stabilizing enzyme-substrate interactions (a salt bridge and an H-bond).

We also structurally verify functional site prediction accuracy within the arginyl-tRNA synthetase family, which is a previously unreported example. As with TIM, we evaluate the same three gap ranges. Structural verification and comparison of these three thresholds is illustrated in Figure 6A–C. The more accommodating PSZ threshold identifies two structurally unique PM clusters. The first is composed of four PMs, and corresponds to the enzyme active site. Several stabilizing enzyme-tRNA and enzyme-Arg interactions are included in this region (Figure 6D). The second PM structural cluster is composed of a single PM, and corresponds to three enzyme-tRNA H-bonds at the tRNA anticodon arm [37]. Making the PSZ threshold more stringent, by widening to the gap range to {-1.0: -2.5}, eliminates two PMs, including the anticodon arm PM. Only one PM is identified at the most stringent level. Like with TIM, the ends of the identified PMs are trimmed at increasingly stringent PSZ thresholds.

Arginyl-tRNA synthetase phylogenetic motifs at the three PSZ thresholds are highlighted. Residues colored red indicate phylogenetic motifs identified using the (A) -2.04, (B) -2.93, and (C) -3.26 PSZ thresholds, which correspond to gap ranges of {-1.0: -2.0}, {-1.0, -2.5}, and {-1.0, -3.0}, respectively. The arginine substrate is colored yellow; the tRNA is colored blue; and the anticodon is color cyan. Using (A), two structurally unique clusters of phylogenetic motifs are identified. One corresponds to the enzyme active site, whereas the other corresponds to three H-bonds between the enzyme and the anti-codon arm of tRNA. (D) is the same (A), but with the rest of the enzyme removed for clarity.

Assessment of functional site predictions

The quantitative assessment of functional site predictions from computational predictions remains an open problem in bioinformatics. Much of the difficulty arises from the fact that function and more specifically, functional sites, are ill defined concepts [38]. Aloy et al. [25] have attempted to standardize assessment of functional site predictions through comparisons to catalytically important residues (see Methods for technical details). Predicting functional sites with an automated evolutionary trace method [7] utilizing structural information on 86 protein families, Aloy et al. demonstrate impressive results: 79% correct, 15% useful information, and 6% Wrong. We use the same assessment strategy on 30 sampled protein families from the COG database (see Table 3). Fourteen of the analyzed families correspond to our earlier manual analysis [12] and the remaining are arbitrarily picked from examples with at least one solved structure. Figure 7 demonstrates that the PM functional site predictions are of similar quality to the overall accuracy reported by Aloy et al. Note that the dataset analyzed in Aloy et al. is not the same as the dataset analyzed here. This result is particularly encouraging due to the lack of structural details in the PM technique.

Pie chart describing the relative accuracy of the automated phylogenetic motif (PM) method using the {-1.0: -2.0} gap range. Assessment is determined using the structure-based approach described in [25]. The relative accuracy of the automated PM method is encouraging as it does not require any a priori structural information.

As Aloy et al. [25] point out, while the quality and robustness of SITE and ACTSITE records within PDB files is of varying quality, their approach does provide an automated and unbiased method for assessing functional site predictions. However, in automated efforts, examples of known "functional sites" will always be missed. For example, assessment of the TIM PM predictions indicates that 3 are correct, 4 provide useful information, and 1 is wrong. The "wrong" prediction actually corresponds to an evolutionarily conserved dimer interface epitope (see Figure 5) that includes several stabilizing monomer-monomer interactions [39]. Despite being far removed from the active site, binding of a small molecule at the dimer interface can inactivate the enzyme [40]. One of the three enzyme-inhibitor contacts occurs from Phe75, which is a residue within the "wrong" PM prediction. As a consequence, it could be argued that this PM is functional. This discussion is included here to encapsulate the ambiguity involved in functional site definitions and the difficulty in assessing their predictions.

Conclusion

In this report, we present an automated algorithm which determines appropriate PSZ thresholds appropriate to functional site predictions. We demonstrate that our methodology is robust enough for large-scale analyses, while sensitive enough to identify known functional sites. For example, the method predicts all structural contacts, including the catalytic residue, between triosephosphate isomerase and its substrate. Additionally, the functionally important flexible "lid" is also identified. In the case of arginyl-tRNA synthetase, PMs correspond to regions surrounding both the amino acid/tRNA acceptor stem and enzyme-anticodon interactions. Using a quantitative structure-based functional site assessment algorithm, we demonstrate that the sequence-only PM predictions compare favorably to those from evolutionary trace approaches that are dependent upon solved structures.

Availability and requirements

-

Project name: MINER

-

Project home page: http://www.pmap.csupomona.edu/MINER/

-

Operating system(s): Platform independent

-

Programming language: PERL

-

Other requirements: Chime

-

License: GNU GPL

-

Any restrictions to use by non-academics: License needed

Abbreviations

- ET:

-

Evolutionary trace

- PM:

-

Phylogenetic motif

- PSZ:

-

Phylogenetic similarity z-score

- PAMC:

-

Partition around medoids clustering

- COG:

-

Clusters of orthologous groups

- TIM:

-

Triosephosphate isomerase

References

Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S: Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J Mol Biol 1999, 294: 1351–1362. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310

Oliveira L, Paiva PB, Paiva AC, Vriend G: Sequence analysis reveals how G protein-coupled receptors transduce the signal to the G protein. Proteins 2003, 52: 553–560. 10.1002/prot.10489

Puntervoll P, Linding R, Gemund C, Chabanis-Davidson S, Mattingsdal M, Cameron S, Martin DM, Ausiello G, Brannetti B, Costantini A, Ferre F, Maselli V, Via A, Cesareni G, Diella F, Superti-Furga G, Wyrwicz L, Ramu C, McGuigan C, Gudavalli R, Letunic I, Bork P, Rychlewski L, Kuster B, Helmer-Citterich M, Hunter WN, Aasland R, Gibson TJ: ELM server: A new resource for investigating short functional sites in modular eukaryotic proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31: 3625–3630. 10.1093/nar/gkg545

Qu K, Martin DL, Lawrence CE: Motifs and structural fold of the cofactor binding site of human glutamate decarboxylase. Protein Sci 1998, 7: 1092–1105.

Lu X, Zhai C, Gopalakrishnan V, Buchanan BG: Automatic annotation of protein motif function with Gene Ontology terms. BMC Bioinformatics 2004, 5: 122. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-122

del Sol MA, Pazos F, Valencia A: Automatic methods for predicting functionally important residues. J Mol Biol 2003, 326: 1289–1302. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01451-1

Lichtarge O, Bourne HR, Cohen FE: An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J Mol Biol 1996, 257: 342–358. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0167

Bickel PJ, Kechris KJ, Spector PC, Wedemayer GJ, Glazer AN: Finding important sites in protein sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99: 14764–14771. 10.1073/pnas.222508899

Armon A, Graur D, Ben Tal N: ConSurf: an algorithmic tool for the identification of functional regions in proteins by surface mapping of phylogenetic information. J Mol Biol 2001, 307: 447–463. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4474

Madabushi S, Yao H, Marsh M, Kristensen DM, Philippi A, Sowa ME, Lichtarge O: Structural clusters of evolutionary trace residues are statistically significant and common in proteins. J Mol Biol 2002, 316: 139–154. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5327

Yao H, Kristensen DM, Mihalek I, Sowa ME, Shaw C, Kimmel M, Kavraki L, Lichtarge O: An accurate, sensitive, and scalable method to identify functional sites in protein structures. J Mol Biol 2003, 326: 255–261. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01336-0

La D, Sutch B, Livesay DR: Predicting protein functional sites with phylogenetic motifs. Proteins 2005, 58: 309–320. 10.1002/prot.20321

Jones S, Thornton JM: Searching for functional sites in protein structures. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2004, 8: 3–7. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.11.001

Hulo N, Sigrist CJ, Le SV, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Bordoli L, Gattiker A, De Castro E, Bucher P, Bairoch A: Recent improvements to the PROSITE database. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32(Database):D134-D137. 10.1093/nar/gkh044

La D, Silver M, Edgar RC, Livesay DR: Using motif-based methods in multiple genome analyses: a case study comparing orthologous mesophilic and thermophilic proteins. Biochemistry 2003, 42: 8988–8998. 10.1021/bi027435e

Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, Rao BS, Smirnov S, Sverdlov AV, Vasudevan S, Wolf YI, Yin JJ, Natale DA: The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 2003, 4: 41. 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41

Penny D, Hendy M: The use of tree comparison metrics. Systematic Zoology 1985, 34: 75–82.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994, 22: 4673–4680.

Felsenstein J: Inferring Phylogenies. 1st edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2004.

Kuhner MK, Felsenstein J: A simulation comparison of phylogeny algorithms under equal and unequal evolutionary rates. Mol Biol Evol 1994, 11: 459–468.

La D, Livesay DR: MINER: software for phylogenetic motif identification. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, in press.

Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ: Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. New York: Wiley; 1990.

MacQueen JB: Some Methods for classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1967:281–297.

Ihaka R, Gentleman R: R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J Comp Grap Stat 1996, 5: 299–314.

Aloy P, Querol E, Aviles FX, Sternberg MJ: Automated structure-based prediction of functional sites in proteins: applications to assessing the validity of inheriting protein function from homology in genome annotation and to protein docking. J Mol Biol 2001, 311: 395–408. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4870

Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM: LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng 1995, 8: 127–134.

Kursula I, Partanen S, Lambeir AM, Antonov DM, Augustyns K, Wierenga RK: Structural determinants for ligand binding and catalysis of triosephosphate isomerase. Eur J Biochem 2001, 268: 5189–5196. 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02452.x

Babbitt PC, Mrachko GT, Hasson MS, Huisman GW, Kolter R, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Kenyon GL, Gerlt JA: A functionally diverse enzyme superfamily that abstracts the alpha protons of carboxylic acids. Science 1995, 267: 1159–1161.

Cooperman BS, Baykov AA, Lahti R: Evolutionary conservation of the active site of soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase. Trends Biochem Sci 1992, 17: 262–266. 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90406-Y

Livesay DR, Jambeck P, Rojnuckarin A, Subramaniam S: Conservation of electrostatic properties within enzyme families and superfamilies. Biochemistry 2003, 42: 3464–3473. 10.1021/bi026918f

DeDecker BS, O'Brien R, Fleming PJ, Geiger JH, Jackson SP, Sigler PB: The crystal structure of a hyperthermophilic archaeal TATA-box binding protein. J Mol Biol 1996, 264: 1072–1084. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0697

Joseph D, Petsko GA, Karplus M: Anatomy of a conformational change: hinged "lid" motion of the triosephosphate isomerase loop. Science 1990, 249: 1425–1428.

Rozovsky S, Jogl G, Tong L, McDermott AE: Solution-state NMR investigations of triosephosphate isomerase active site loop motion: ligand release in relation to active site loop dynamics. J Mol Biol 2001, 310: 271–280. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4673

Rozovsky S, McDermott AE: The time scale of the catalytic loop motion in triosephosphate isomerase. J Mol Biol 2001, 310: 259–270. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4672

Wierenga RK, Borchert TV, Noble ME: Crystallographic binding studies with triosephosphate isomerases: conformational changes induced by substrate and substrate-analogues. FEBS Lett 1992, 307: 34–39. 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80897-P

Livesay DR, La D: The evolutionary origins and catalytic importance of conserved electrostatic networks within TIM-barrel proteins. Protein Sci 2005, 14: 1158–1170. 10.1110/ps.041221105

Delagoutte B, Moras D, Cavarelli J: tRNA aminoacylation by arginyl-tRNA synthetase: induced conformations during substrates binding. EMBO J 2000, 19: 5599–5610. 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5599

Whisstock JC, Lesk AM: Prediction of protein function from protein sequence and structure. Q Rev Biophys 2003, 36: 307–340. 10.1017/S0033583503003901

Kursula I, Wierenga RK: Crystal structure of triosephosphate isomerase complexed with 2-phosphoglycolate at 0.83-A resolution. J Biol Chem 2003, 278: 9544–9551. 10.1074/jbc.M211389200

Tellez-Valencia A, Olivares-Illana V, Hernandez-Santoyo A, Perez-Montfort R, Costas M, Rodriguez-Romero A, Lopez-Calahorra F, Tuena DG-P, Gomez-Puyou A: Inactivation of triosephosphate isomerase from Trypanosoma cruzi by an agent that perturbs its dimer interface. J Mol Biol 2004, 341: 1355–1365. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.056

Schorken U, Thorell S, Schurmann M, Jia J, Sprenger GA, Schneider G: Identification of catalytically important residues in the active site of Escherichia coli transaldolase. Eur J Biochem 2001, 268: 2408–2415. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02128.x

Blanchard CZ, Lee YM, Frantom PA, Waldrop GL: Mutations at four active site residues of biotin carboxylase abolish substrate-induced synergism by biotin. Biochemistry 1999, 38: 3393–3400. 10.1021/bi982660a

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for making us aware of the structure-based functional site assessment algorithm described in Aloy et al., J. Mol. Biol., 2001. Shankar Subramaniam is acknowledged for a number of valuable suggestions and proof-reading the manuscript. This work was partially supported by an American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund grant (36848-GB4), a National Science Foundation MRI-grant (0321333), and a supercomputer allocation (MCB00018N) from the National Center for Supercomputing Applications to D.R.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

D. La was primarily responsible for the development and testing of the described methodology. D.R. Livesay oversaw the research. Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

La, D., Livesay, D.R. Predicting functional sites with an automated algorithm suitable for heterogeneous datasets. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 116 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-116

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-116