Abstract

In recent years, the concept of circular economy has gained increasing attention from both businesses and governments. The African continent has started to adopt circular economy–related policies at national or regional levels, but it is not yet mainstream. Literature on circular economy has mainly focused on developed countries in the global north with limited attention given to the potential of circular economy for developing countries especially in the context of African islands. In this paper, we fill this gap by providing existing baselines regarding CE for 9 African islands and present their existing strategies that could foster the development of a circular economy. Adopting the Ellen MacArthur Foundation diagram and the ReX framework, we use different components of the combined frameworks to situate the various initiatives. We show that African islands have led an array of initiatives especially in waste management and also in regenerating natural resources. However, various challenges remain, such as the lack of national umbrella frameworks that would ensure circularity across actions. Countries with more favourable socio-economic and political contexts such as Reunion Island or Mauritius implement policies relating to a circular economy. However, these countries and others, such as Maldives or Seychelles, also have a high level of material consumption that requires changes from production to consumption stages. Countries with challenging contexts, such as Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Comoros and to a lesser extent Cabo Verde, have less dedicated policies but various dispersed activities such as using renewable energy that could contribute to circularity. Extraction of natural resources in these countries remains an important source of growth that requires a systemic change towards circularity. Embracing a circular economy presents various opportunities to African islands especially considering the blue economy agendas adopted in these islands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural resource use and material consumption have exponentially increased in the past 20 years [1, 2]. This has led not only to various environmental issues, such as the biodiversity crisis, but also to socio-economic issues, notably with the widening of the inequality gap [3, 4]. The global economic system and the capitalist manners of exploiting natural resources are considered to be major contributors to the situation [5]. Since the 1960s, alternative systems that are restorative by design have been promoted, including the need for a circular economy (CE) [6]. The concept of a CE is progressively evolving into a mainstream idea and has seen its implementation under other concepts such as the green and, more recent, blue economies [7, 8]. The CE is further being associated as a necessary step to achieve sustainable development [9]. It has received increasing attention from governments, the private sector and academia [9, 10]. The European Union (EU), for example, adopted the CE Action plan in 2015 to help stimulate the EU’s transition towards a CE [11]. Countries like France and the Netherlands are seen as championing CE implementation. Global initiatives are also burgeoning, such as the Global Plastic Action Partnership, Circular Electronics Action Partnership or the Global Battery Alliance [12]. For African islands and African countries in general, excluding Reunion Island, the circular economy is still a nascent concept [13]. However, it represents an opportunity to overcome the challenges that the African islands face, including the reliance on import for goods and material, and the accumulation of waste that degrades the environment [14, 15]. The Indian Ocean Commission, through its recent blue economy strategy, has provided a pathway to address these challenges [16].

The aim of this article is to look at the level of implementation of the CE in 9 African islands. For the African continent and islands, the CE is a fairly new concept with a few exceptions, such as South Africa or Reunion Island which have implemented some CE principles and initiatives in the past 10 years [17, 18]. The CE literature in Africa and its islands has mainly focused on the management of e-waste and agricultural waste, the recycling of composite materials, renewable energy and the appropriation and acceleration of CE principles by governments and businesses [13, 19,20,21,22]. For African islands in particular, various initiatives have taken place that are linked to CE without being labelled as such. Our paper is the first of its kind, through assessing existing local and national initiatives and framing them under the CE framework. Furthermore, in the current blue economy agendas that many African islands have adopted, the circular economy concept presents the opportunity to build a strong blue economy that could be less reliant on external inputs. It is especially relevant for key areas of the blue economy that build on harvesting/extraction, the use of renewable and non-renewable resources, and commerce and trade. Implementing a CE presents the opportunity to achieve sustainable and inclusive blue growth. The CE framework that is used in this article is an adapted CE framework combining that of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the ReX frameworks [23, 24].

Following this introduction, the article provides a brief description of the theoretical framework based on the CE system diagram. It then presents the current frameworks and strategies within the 9 islands that can be related to a CE. It continues with a discussion on the state of implementation of the CE and the challenges that African islands face. It concludes with the opportunities that can be developed within African islands to boost their CE and contribute to sustainable blue economies.

Developing a Circular Economy Framework for African Islands

In this article, we use the definition of a CE adopted by Kirchherr et al. [25]. They conceptualised CE as ‘an economic system that replaces the “end-of-life” concept with reducing, alternatively reusing, recycling and recovering materials in production/distribution and consumption processes’. (ibid, p. 264). The CE operates at different levels from the micro-level (products, companies, consumers), the meso-level (eco-industrial parks) and the macro-level (city, region, nation and beyond) (ibid). Under the global framework of sustainable development and more recently the adoption of blue economy agendas, African islands have increasingly adopted sustainable practices in terms of production and consumption. These are, however, dispersed and often siloed under sectoral policies.

While the literature on circular economy has been booming in developed countries looking at strategies in various sectors and linking theory and practice [9, 10], studies in the African context have been limited. Various studies have focused on South Africa which has explored the implementation of circular economy in various sectors such as waste management, renewable energy and manufacture [18, 26]. The subject of recycling and managing e-waste has been addressed in Nigeria and Ghana [27]. Mutezo and Mulopo [22] have explored the potential of circular economy principles applied to the renewable energy sector in Algeria, Nigeria, Morocco, South Africa and Egypt. Desmond and Asamba [13] looked at policy and existing efforts related to circular economy in countries on the African continent. A fewer studies have looked at African islands. Kowlesser [28] investigated the different initiatives related to circular economy in Mauritius and the needed policies to advance the use of the concept. The subject of renewable energy has also been explored in Mauritius and Reunion Island (France) through various options such as cogeneration or wind energy [17, 29].

In this article, a framework is provided to analyse where African islands are in implementing a circular economy. To address both natural resource extraction and material consumption, the circular economy system diagram of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation is used as a theoretical framework (Fig. 1). The diagram combines the biophysical and technical cycles to address both the use of natural resources and material production and consumption. The framework is based on three principles: preserve and enhance natural capital by controlling finite stocks and balancing renewable resource flows (P1); optimise resource yields by circulating products, components, and materials at the highest utility at all times in both technical and biological cycles (P2); and foster system effectiveness by revealing and designing out negative externalities (P3) [30].

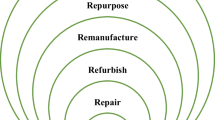

Within the technical cycle that addresses material stock management, we integrated the ReX framework [24]. The ReX framework has been designed to cover 8 different strategies of circularity within material stock management. It includes the concepts under the 3R framework (reduce, reuse, recycle) that is commonly used [31] and it also integrates other concepts that further details strategies under reuse and recycle. These are strategies such as recover, repair, refurbish or repurpose that have been developed within extended frameworks such as 4R or 9R [32,33,34]. The ReX framework also provides a straightforward picture of the three main stages of production ‘Pre-Use, Use and Post-Use’.

Methodological Approach in the African Islands’ Context

The research is based on an analysis of 9 African islands and coastal states: the Union of the Comoros (COI), Cabo Verde (CVI), Guinea-Bissau (GBS), Mauritius (MAU), Madagascar (MDG), the Maldives (MDV), Reunion Island (REU), Seychelles (SEY) and Sao Tome and Principe (STP). Considering the sparse data and the innovative character of implementing a CE in most of the countries studied, we adapted our research methods to gather data from various sources. First, relevant CE-related initiatives were recorded from an online search of key initiatives in each country that could fit under the CE presented above. Keywords from the different components of the ReX framework were used for the search as well as keywords of initiatives of marine resource use and conservation, waste, and plastic management. From this search, different sources emerged including project descriptions and documents, policy and legal texts, consultancy reports and websites of ongoing projects. Second, one of the authors attended a workshop organised by the Indian Ocean Commission in December 2019 during which the 9 islands presented their ongoing efforts towards a CE. The presentation of each country was collected and used to gather information on national initiatives. Third, to further assess the state of CE implementation, various indicators were used to assess the level of material use and resources extraction in the 9 islands (Table 1).

Since the CE is still an innovative concept in most developing countries, common indicators used in European countries (such as recycling rate or biogas production) are not available yet for most African countries and especially islands. We therefore chose publicly accessible indicators that could respond to some aspects of the circular economy and relevant to the islands’ context. Fisheries and extraction of natural resources indicators were key because sectors such as agriculture or mining are driving the economy especially in less developed islands like Comoros, Madagascar and Guinea-Bissau. Renewable energy, as one of the pillars of the circular economy (EMF 2015), is present in the different islands and has the potential to be upscaled. Assessing regeneration is challenging. For islands, protection of the national waters towards biodiversity conservation was chosen as the most applicable because of the countries’ large marine space. Export and import and material consumption were chosen since the insular characteristic of the countries has a strong impact on reliance on external products and ultimately on the ability to have more localised products’ circuit, to reduce waste and to implement reuse strategies. Waste generation is a key indicator for African islands as different key sectors of the economy such as retail, tourism and food consumption generate high levels of waste.

Policy and Legal Frameworks Promoting a Circular Economy in African Islands

For African countries, including African islands, the implementation of the CE concept is still recent [13]. However, most countries have different laws and policies that promote the principles of a CE despite not addressing it directly (Table 2). All 9 African islands have laws and policies that cover the use of natural resource and management of renewable flows. These include texts that regulate forestry and fisheries activities, specific forestry and fisheries codes, environmental laws and biodiversity strategies. They also cover specific texts aimed at protecting ecosystems and species such as protected areas and water codes.

In terms of stock management, all of the countries studied have developed policies and laws that relate to waste management especially regarding solid waste. Most of the African islands have also addressed the issue of plastic by prohibiting the use of plastic bags or single-use plastics. Countries that have not implemented such prohibition have adopted phasing out policies. Some countries also have regulations regarding the activity of recycling.

In terms of performance of the countries regarding CE policy development, Reunion Island is the most advanced. In addition to those mentioned above, it has adopted laws on energy transition (2019), a ban on plastic bags, a recent law on the fight against waste and a policy on the circular economy (2020). Under the impulsion of France, Reunion Island also adopted a Regional Action Plan for the Circular Economy. The plan has five objectives including coordinating the transition towards a CE, activating the levers of the transition, improving production and consumption, and developing loops between resource use and impacts.

Most African islands have also developed blue economy laws and strategies that promote the sustainable use of marine resources, protection of marine ecosystems and waste management. That is the case of Cabo Verde (Blue Growth Charter), Comoros (the Strategic Framework for a Policy National on Blue Economy), Mauritius (Ocean Economy Roadmap), Reunion Island (Law on the Blue Economy) and Seychelles (Blue Economy Strategic Roadmap and Blue Economy Action Plan). Countries that are in the process of developing such blue economy policies include Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar and Sao Tomé and Principe. Blue economy policies that promote the sustainable use of resources within planetary limits can be considered as addressing the renewable flow management part of the CE framework.

Circular Economy Indicators in African Islands

The first part of our analysis consisted of establishing the levels of resources used in the 9 African islands. To comply with the adapted CE framework we developed, we looked at indicators that would provide a baseline for the two main parts of the framework. For renewable flow management, we assessed the levels of extraction of natural resources as well as the levels of protection that could lead to regeneration of stocks. For the material stock management, we assessed the level of material consumption and waste generation.

State of Natural Resource Extraction

For African islands, the extraction of natural resources is an essential part of their economies. Most African islands have experienced an increase in their domestic extraction in the past 40 years with countries like Cabo Verde or Comoros seeing an increase of more than 500% in domestic extraction [35]. Every year, about 45 million tonnes of resources are extracted from the African islands, with Madagascar and Mauritius extracting the most resources including biomass and non-metallic minerals (Fig. 2).

For a further look at the extraction of living resources, the case of fisheries, aquaculture and bio-prospection represents sectors for African islands that are integral parts of the CE. In fisheries, the 9 African islands have important production levels (Table 3) that are key to the national economies and food security of the countries. The African islands studied have a combined yearly production of around 500,000 tonnes every year [37].

In a CE, extraction is aimed at manufacturing products with the design that products have multiple life cycles. For the case of fisheries, fisheries products can have various uses beyond consumption, the production of fishmeal from fish waste is widely practised within the African islands. However, the production is low. The entire African production of fishmeal does not exceed 200,000 tonnes (as of 2018) which represents less than 3% of global production [37]. Some islands have also invested in producing by-products using fish parts. One such example is in Mauritius, where, operated by some private companies (for example, Marine Biotechnology Products, Goia Tuna Oil), fish oil is produced from tuna heads unused in the canning industry. The fish oil is sold as a food supplement.

For aquaculture, the production within African islands is still very low following the trend in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fish production from aquaculture in Sub-Saharan African still represents less than 1% of the global production. African island countries such as Madagascar, Reunion Island and Mauritius are involved in aquaculture and mariculture. While the aquaculture sector within the Indian Ocean Commission countriesFootnote 1 alone is estimated at EUR 23.3 million per year, the production is mainly for consumption and export [38]. Activities to improve life cycles for the countries involved in aquaculture would include waste management and water treatment, two aspects that are recognised as requiring improvement in aquaculture practices.

For non-living resources such as oil and gas as well as renewable energy and minerals, African islands have not fully developed activities in these areas, despite the substantial potential.

Regarding oil and gas, in 2014, important deposits were discovered within the Mozambique Channel and provide potential of extraction for countries in the region [39]. African islands such as Maldives and Guinea-Bissau also have existing deposits that present the opportunity of exploitation. Since the discovery of oil and gas deposits within African islands’ marine space, exploration activities have taken place in countries like Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau and Seychelles. Since extraction itself has not taken place yet, it is not possible to assess how the CE principles are implemented. However, water and technical materials from refineries have been recycled and reused in other countries [40, 41].

For renewable energy, African islands have different levels of consumption (Fig. 3). Countries like Guinea-Bissau and Madagascar strongly rely on renewable energy whereas countries like Maldives, Mauritius or Sao Tomé and Principe have a very low consumption [42].

The western Indian Ocean has been assessed presenting the potential for developing energy from ocean-based sources such as deep-ocean temperatures, tidal energy, ocean currents and wave energy [39]. The technologies for such options are not yet available for the countries of the Indian Ocean.

Levels of Ecosystem and Species Protection

Another important principle within the CE is regeneration or ‘the promotion of self-renewal capacity of natural systems with the aim of reactivating ecological processes damaged or over-exploited by human action’ [43, p. 769]. Within a CE, high priority is given to natural systems both for the use of their ecosystem services and for their protection and restoration to allow them to flourish.

For the African islands, in addition to terrestrial systems, the marine system plays an essential role in sustaining economies especially considering the large national water and high seas that surround the islands. Therefore, various biodiversity conservation policies and actions as well as initiatives towards sustainable management of fisheries and marine resources can be included within this regeneration. To assess the level of regeneration in the cases studied, the indicator used was the level of protection of the marine ecosystem, mainly through marine protected areas (Table 4). While there are a number of marine conservation–related activities in the region, it is difficult to quantify their impact on the regeneration of renewable flows.

Material Stock Indicators

To assess the level of material used and investigate the level of stock management according to the framework we developed in the ‘Developing a Circular Economy Framework for African Islands’ section, we used existing indicators linked to levels of consumption and waste generation mobilised in other studies (see, for example, in [36, 44]).

For material consumption, in line with their development status, more advanced African islands have higher material consumption [35] and waste per capita [45, 46] compared to developing African islands (Figs. 4 and 5). These are key indicators that show potential challenges in implementing circularity in waste management sector especially in more advanced islands. The issue of plastic in particular represents an important threat to the ecosystems of the African islands. With a total plastic consumption of more than 450,000 tonnes in 2010 [47], the African islands, especially more developed ones such as Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles, have extremely high quantities of plastic per capita (Fig. 6). All African islands studied (apart from Reunion Island where data was not available) have high number of products that are imported which is can be problematic in implementing circularity and reduce strategies (Fig. 7).

Domestic material consumption per capita within African islands (excluding Reunion Island: 10.4 tones/capita in 2015). Source: materialflows.net. Accessed October 8th, 2020 and [36]

Plastic waste generated in kg per capita/per day within African islands (excluding Reunion Island). Source: [47]

Number of products exported and imported within African islands (excluding Reunion island). Source: https://wits.worldbank.org/. Accessed October 8th, 2020

Beyond Indicators: a Qualitative Analysis of Existing CE Strategies

This section moves to a more qualitative assessment of CE strategies in African islands. As material consumption and waste management have matured into more pressing issues, especially in the African islands, we will mobilise the ReX framework (presented in Fig. 1) to provide a picture of existing initiatives within the strategies of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Recover. We will then present some key regeneration strategies that exist within the case studies that could contribute to the regenerative part of the CE presented above.

Reducing Material Consumption

The concept of reduction (‘Reduce’) at the pre-use stage involves various ideas including eco or sustainable design, designing products that last longer or have multiple life cycles, and the use of less material in production or dematerialisation [10]. It also covers the idea of consuming less, using products for longer or building more emotional attachments to products to avoid discard [24].

For the African islands, a range of activities and initiatives are in place to promote the reduction of consumption, especially linked to single-use plastics. Industries such as tourism and fisheries are at the forefront of taking part in such initiatives. Common initiatives across the African islands include campaigning against the use of plastic bags and bottles (see, for example, in Table 5), environmental education of the general public regarding reduction of consumption, and waste management or the use of biodegradable fishing aggregating devices (FADs) rather than plastic-based FADs in tuna fisheries in the Indian Ocean.

There are also Reduce schemes established in specific countries. Mauritius, for example, has developed two schemes. First is the deposit-refund scheme on glass bottle, led by local companies. The scheme establishes a deposit fee for 700-ml and 330-ml glass bottles. It helps to ensure that the glass bottles are returned to the retailer and then collected by the beverage manufacturers [28]. Second is the duty excision on non-biodegradable plastic food containers. The scheme promotes responsible consumption and production by imposing a tax on single-use plastic food containers, thereby reducing the generation of single-use non-biodegradable plastic food containers (ibid). In Madagascar, the government has supported the creation of ecovillages within which ecological materials found locally are used to build houses [48].

Reusing Natural Biomass

The concept of ‘Reuse’ covers various strategies within the CE and promotes a sharing economy. According to Sihvonen and Ritola [24], Reuse includes strategies from direct reuse to remanufacture or resynthesis (Table 6).

For the 9 African islands, the reuse strategy can reduce their reliance on imports but it also constitutes an important element towards circularity. The initiatives that are shared and mainstream amongst the African islands include compost production and repurposing (Table 7), and campaigns against food waste.

Recycling Organic and Plastic Waste

Recycling (‘Recycle’) is one of the most mainstream and accepted strategies within the production and consumption cycle. Recycling can be defined as ‘any recovery operations by which waste materials are reprocessed into products, materials or substances whether for the original or other purposes’ [24, p. 642]. Recycling involves restoring products through their original or downgraded state so that they can be suitable for different purposes.

For the African islands, the strategy of recycling has been adopted at different levels and in different forms. We identified four common initiatives: (1) the integration of recycling within waste management policies, including through the creation of recycling centres, (2) establishing collecting points of recyclable waste, (3) the development of recycling activities at different levels, including within communities (for the case of Maldives and Seychelles), the private sector (for the case of Mauritius, Reunion Island, Guinea-Bissau and Comoros) and at the state level (for the case of Madagascar and Cabo Verde), and (4) the transformation of recycling waste into needed material, including for construction and public infrastructure such as streets (Table 8)

Recovering Energy and E-waste Parts

Recovery (‘Recover’) is one of the less mainstream strategies with the R framework. Although it was adopted by the European Union (2008) [28] and exists within the 4R to 9R framework, it is less developed in terms of its implementation globally and especially in developing or coastal countries [45]. Sometimes considered as covering Reuse and Recycle, the Recover strategy in the ReX framework involves retrieving valuable or hazardous materials during the post-use phase [24]. This strategy involves, for example, energy or metal compound recovery processes (ibid).

For the African islands, the strategy of recovery can be embedded within recycling practices. The generation of biogas from household waste, a practice developed in various African islands, can be considered an energy recovery strategy.

In terms of material recovery, countries have had different involvements. A common practice within the African islands and especially in less developed African islands like Madagascar, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde, is the recovery of metal and other components by informal recyclers [49, 50]. These recovery activities target different types of metal as well as e-waste [50]. For more advanced countries such as Mauritius and Reunion Island, the private sector has been a key player in developing recovery activities including the recovery of energy and metal from old batteries and e-waste. Companies (Wecycle, Recyclage Valorisation Environnement—RVE) have developed processes to collect and recover material from e-waste that can be reused for refurbishment purposes or for different uses entirely. Another initiative in Reunion Island is the industrial waste collection and recovery, where a private company (Inter’Val) collects and recovers parts of industrial waste (filters, containers, paints, etc.) to be exported.

Regeneration Strategies

African islands share common practices of regeneration (‘Regenerate’) that, while not labelled as such, contribute to the reactivation of ecological processes, as described in the EMF framework. Amongst all of the African islands, the establishment of marine protected areas has taken place (Table 6). Each African island has established one or more marine protected areas to help species flourish without the threat of human action. The countries studied have also adopted legislation protecting endangered species, such as sharks, from being harvested. Initiatives such as protection and restoration of coral reefs, mangroves and other wetlands are also taking place.

Specific regeneration initiatives have also been undertaken by some countries and can be recorded as contributing to more sustainable use of marine resources. Madagascar, Mauritius and Comoros have established fisheries closures for species such as octopus, crab or lobster. They are managed under temporary closures of the fishery to ensure that juveniles are not caught so that species reach reproductive maturity [51]. Madagascar, and recently the Seychelles, has also established LMMAs—locally managed marine areas. LMMAs are specific marine areas, often coastal, that are managed by local communities. The management is shaped by a set of rules that prevent destructive use and designates specific areas that cannot be accessed by users in order to protect juvenile species [52]. In Seychelles, a Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) process has taken place that allows government and natural resource users to determine together the various uses and zoning of national waters. Seychelles has been leading such a process and finalised its MSP in 2019. Through MSP, the Seychelles managed to designate 30% of its national waters to be protected under different types of zoning [53]. In the Maldives, certification schemes such as the Marine Stewardship Council for fisheries products, such as tuna, allow the resources to be managed under environmental criteria and rules that the fish stocks benefit from [54]. Finally, member parties to the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission established catch limits to allow the overfished yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean to recover. These catch limits aim to reduce fishing effort in the Indian Ocean region [55].

Discussion

African islands have had different levels of involvement in implementing CE concepts (Table 9). Regarding the extraction of natural resources, African islands are involved in various management initiatives from which lessons could be shared including in terms of fisheries and aquaculture as well as renewable energy. For other fields such as oil and gas, offshore renewable energy and bioprospection, the African islands studied have not yet developed these activities. This represents an opportunity to build frameworks and policies for these activities that comply with the needs of a circular economy. African islands have also progressed towards protecting natural systems from degradation. However, efforts are still limited in terms of protecting marine areas in comparison to the size of EEZs. Efforts are also not consistent within the region with some countries like Seychelles and Mauritius further advanced in achieving protection targets. Considering the reliance of the African islands on the oceans, regeneration is a key component in achieving a CE. While there are initiatives that constitute a good start on energy recovery and feedstock extraction, these are localised and of small scale. Activities that specifically address marine ecosystems are also limited but could be enhanced through ongoing conservation activities.

Implementation of CE concepts within the ReX framework has also been highly variable, which is not surprising considering the diversity of socio-economical contexts of the islands, as well as the relative novelty of CE concepts. Within the Reduce strategy, especially within the production cycle and promotion of sustainable designs, there are few recorded initiatives thus far. Since African islands strongly rely on imports for their goods, production is also often out of the hands of the countries.

African islands have developed a vast array of initiatives for the Reuse strategy. One of the challenges of the Reuse strategy for the African islands is to build the capacity in the different industries to repair, repurpose and refurbish products. However, in developing African islands, the informal sector represents a rich field of exploration as it is where different activities relating to repair, reuse or resale take place widely. There is, however, limited data regarding these practices that are key to the CE. This requires more research and investigation on the potentiality presented by such activities.

In terms of recycling strategies, the market presents various opportunities with existing operators not able to respond to the large demand that waste management requires in each country. So far, only key products such as PET and glass bottles are widely recycled. There is a need to better investigate the availability of other types of recyclable waste and especially build technical skills at different levels to implement transformation activities. The activities presented above show the diversity of experiences within the African islands and from which the replicability could be studied. Countries with similar socio-economic contexts such as Mauritius, Maldives, Reunion Island and the Seychelles could learn from each other, as could less advanced countries such as Comoros, Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde.

There are few records of initiatives that directly refer to the Recover strategy. It is, however, highly probable that the recovery sector is more developed than what it appears within African islands especially considering the informal activities that take place in some of the countries. What is therefore missing is a promotion and boosting of these activities to create more value for the countries, and the provision of benefits for workers involved in such activities.

The Need for Technical Capacity

One of the key challenges that African islands face in transitioning to a CE is the limited technical capacity. The low population in most of the African islands often results in the inability to implement interventions or develop national strategies due to lack of technical capacity. Even in Reunion Island, the boosting of the CE stems from France’s advanced CE policy. One of the key challenges for African islands is therefore the limited human resources that have the expertise to develop technically advanced CE activities. The African islands also lack human resources to implement activities such as those within the ReX framework, and especially in waste management. For the latter in particular, recycling and recovering of waste is often not considered an attractive employment for local people and is sometimes associated to a marginalised segment of the population [45, 50].

Another important gap is the limited data available as well as the capacity for data collection. Lack of data affects both knowledge on natural flows as well as knowledge on material and waste. Consequently, it can be difficult to adopt the best strategy in the different spheres of the CE where data is scarce for the needs of new initiatives. Furthermore, there is also limited collection of data that assess the effectiveness of existing projects.

African islands require capacity building in six key areas: the development of a CE national strategy; technical knowledge in energy recovery and feedstock extraction initiatives; expertise in expanding recycling beyond plastic and PET bottles; technical knowledge in material recovery; data collection regarding natural flows and material use; and data collection assessing existing initiatives and projects.

The field of reuse within African islands is also one that requires more development. While some skills might be available for small repair of material, and common in developing economies, capacities around refurbishment and remanufacturing are close to non-existent.

In terms of management of natural flows, the African islands have succeeded in adopting environmental policies and implementing projects and activities towards the protection of natural ecosystems and marine resources. These, however, still need reinforcing. A number of lessons learned within the African islands (presented in the ‘Regeneration strategies’ section) could guide countries that are less advanced.

In terms of awareness about the CE, further campaigns are needed at all levels of the population, but especially at the production and policy levels. Within the general public, knowledge about the CE economy is extremely limited, if not non-existent. However, the African islands’ populations are increasingly aware of the need for environmental protection and waste management, including problems related to consumption and plastic. What is thus missing is a broader awareness campaign on how current and future initiatives could contribute to a circular economy that would be beneficial to the African islands’ populations.

Stronger effort to integrate CE approaches is particularly necessary at the production level. Companies extracting natural resources and producing goods in Africa (including in the African islands) have not yet integrated a CE approach [13]. This is mainly due to the fact that production and extraction in African islands (and developing countries in general) tends to follow a linear and accumulative approach that relates to achieving growth (ibid). The benefits of a CE approach are then little known within companies. The experience of Reunion Island in involving companies and promoting the private sector’s involvement in building a CE is a key experience for the African islands and represents an opportunity for exchanges between similar industries.

At the policy level, governments of the African islands have only engaged in CE discussions in the past 5 years, with the exception of Reunion Island. Governments still have limited awareness of the requirements and benefits of the CE especially in achieving a sustainable and inclusive blue economy.

Finally, the limitation of funds is a key challenge in developing and implementing activities within the CE. As a common issue that developing African islands in particular face, the lack of financial resources available and the reliance on foreign aid to develop projects are a significant limitation. Even within the current blue economy agenda, main initiatives are led by funders such as the World Bank or the IOC. Seychelles have managed to raise US$15 million in funds from international investors for ‘blue bonds’ designed to support sustainable marine and fisheries projects [56]. Even with this progress, the results from these blue bonds are yet to be presented. Furthermore, while Reunion Island has raised most of its funds for CE through its state budget, other African islands might not have the budget to specifically foster CE interventions.

The Weight of Differentiated Socio-economic Contexts

African islands have very diverse national priorities. The more advanced countries are at the stage where some reflexion of circularity can be undertaken especially in light of increasing consumption and accumulation of waste. The less advanced countries, however, are still aiming at achieving development often relying on more extractive and linear economies. Waste management cumulatively adds to the issues that developing countries are increasingly facing. That said, a CE economy represents an opportunity for developing countries to achieve development under a CE framework that is more regenerative for natural resources and addresses waste issues from the material production stage to post-use. The challenge then lies within changing the paradigm at the highest level for less advanced countries. African islands like Comoros have already started this reflexion in its blue economy strategy and could serve as an example for other developing African islands.

Another aspect is the engagement of the African islands in developing their blue economies. There is a need to align national priorities with circularity rather than growth. Some prospective activities under the blue economy aspirations of countries are strongly related to linear growth. Visions such as increasing seabed mining or further development of fisheries might have contradicting values with the CE principles. It can therefore be a challenge for countries to achieve blue growth within a CE.

A further obstacle is showing the relevance of CE for local realities. As the implementation of a CE is emerging in western countries, making such a concept applicable to developing African islands is of notable importance. In countries like Madagascar or Guinea-Bissau, extraction of resources is where wealth resides and consumption of goods is seen as a sign of progress. Applying a CE economy approach in such a context therefore can be seen as regression from this perspective. In countries where the majority of the population rely on day-to-day income and expenditure, concepts such as extracting or consuming less can appear contradictory to development and economic growth. Within the developing African islands in particular, CE can be seen as a western concept that will impose limits on individual and national economic growth. On the other hand, in more advanced African islands, the implementation of a CE might affect many industries that have strongly relied on extraction such as fisheries. Industrial fishing, for example, is an important source of revenue for African islands in the Indian Ocean. Implementing a CE might require a different approach to fisheries that is more geared towards the protection of resources and the reduction of production to a more sustainable level. Economies of countries like Seychelles that are highly reliant on tuna fisheries, for example, might need to adjust their industrial fisheries practices for more circularity and better use of resources.

The diverse socio-economic context within African islands can present strong obstacles to a harmonised CE strategy. While the principles of CE could be agreed amongst countries as helping to achieve sustainable development, their implementation requires a highly differentiated approach that considers the specificities of each of the African islands.

Potential Institutional and Political Obstacles

In order to implement a CE, a myriad of institutional and political obstacles would need to be overcome by African islands. While we have shown that there are already opportunities to develop the CE, the disparity of existing initiatives shows that there is also a risk of having uncoordinated and potentially contradictory policies that do not comply with the CE principles. Similarly, laws and regulations on specific CE activities are lacking in all of the African islands, with the exception of Reunion Island.

A second challenge is the limited means that are currently available to implement CE projects and systematic changes at the state level. This includes not only the limited financial means as presented above, but also the lack of institutional structures and infrastructure that are needed to develop and implement circularity. This is evidenced by the fact that current initiatives in waste management are often project-based rather than being long-lasting initiatives. Efforts such as recycling or material recovery require substantial infrastructure and equipment that are not necessarily available within the African islands, especially the developing ones.

The third challenge is political. While the African islands have committed to achieving sustainable development, political will is not homogenous amongst all of the countries. Many of the African islands are also subject to political instability and crisis. In this context, undertaking a systemic transformation such as the shift towards a CE will be highly dependent on national priorities of political leaders. In countries like Madagascar or Guinea-Bissau, recurrent political crises present a serious threat to enabling a systemic change. Governments that have agreed to a CE agenda today could be replaced tomorrow. The lack of policy continuity will strongly affect the ability of politically unstable African islands to fulfil their commitments towards a CE.

In line with this instability and political turnover, power relations between governments and extractive/exploitative industries often dominate decision-making, especially in developing countries [4, 57]. Industries such as mining or industrial fishing have strong influence on state actors and on environmental policy making. Often presenting their financial contribution to national economies, they can be reluctant to agree or adhere to changes in policy and influence decision makers through lobbying. Such power dynamics are often overlooked especially in developing countries and require particular attention if any systemic change is to be achieved.

Conclusion: Pathways Towards a CE

Our study has shown that African islands are at different levels of implementing a CE but all have developed discreet CE-related interventions. This is highly relevant for policy-makers and entities that promote CE as we highlighted initiatives that could represent the basis of a CE as well as the challenges that need to be addressed in islands and the African context. Despite the challenges presented above, the CE presents an array of opportunities that the African islands could benefit from. As most of the countries studied have now embraced the blue economy agenda, the CE principles could help the African islands develop ocean-based activities that are both regenerative and rely on the management of material stock. This is particularly relevant for prospective activities within the blue economy such as seabed mining, bioprospection, or offshore oil and gas extraction.

The second substantial opportunity from the CE is job creation. While technical capacity is currently limited within African islands towards the implementation of a CE, there are, however, areas (especially within material stock management) that will lead to job creation. From recycling to reuse and repair frameworks, there are strong opportunities to create jobs and reinforce human resources in these areas. If integrated into national strategies, these activities can be promoted by governments as key to sustainability.

Another opportunity for the blue economy agenda is to strongly address the issue of plastic waste that represents a real threat for the coasts and marine ecosystems of the African islands. By promoting circularity, the question of waste, and plastic waste in particular, is addressed holistically, from reduction of consumption to recycling. Adopting a CE framework would provide African islands a strong framework to tackle plastic waste. It can also bring interest and funding to the African islands.

Waste management has been a key area of progress for different countries that have adopted a CE. It is therefore an important field where the African islands would not only benefit from external experiences but also from support by various entities involved in waste management. Sharing of experiences and best practice can provide countries with support and reassurance in implementing changes toward a circular economy that result in better waste management. An area that our study could not address properly was the opportunities in the informal sector regarding waste management and valorisation due to a lack of data and official records on these activities. Developing African islands in particular have a rich and diverse informal sector regarding waste and require more research on its impact and contribution towards a concept such as CE.

The African islands studied have initiated various strategies that comply with the CE principles and framework. However, they are implemented under different policies and regulations. This prevents a holistic approach in achieving a CE. African islands need overarching frameworks that link natural resource extraction and material consumption as described by a CE. This will allow a more coordinated approach and will promote regenerative activities, such as marine protected areas or waste recycling, that might currently be somewhat marginal.

Notes

The IOC members include the Union of the Comoros, France (for Reunion Island), Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles.

References

Schandl H, Fischer-Kowalski M, West J, Giljum S, Dittrich M, Eisenmenger N, Geschke A, Lieber M, Wieland H, Schaffartzik A, Krausmann F, Gierlinger S, Hosking K, Lenzen M, Tanikawa H, Miatto A, Fishman T (2018) Global material flows and resource productivity: forty years of evidence. J Ind Ecol 22(4):827–838

Wiedmann TO, Schandl H, Lenzen M, Moran D, Suh S, West J, Kanemoto K (2015) The material footprint of nations. PNAS 112(20):6271–6276

Marques A, Martins IS, Kastner T, Plutzar C, Theurl MC, Eisenmenger N, Huijbregts MAJ, Wood R, Stadler K, Bruckner M, Canelas J, Hilbers JP, Tukker A, Erb K, Pereira HM (2019) Increasing impacts of land use on biodiversity and carbon sequestration driven by population and economic growth. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3(4):628–637

Teixidó-Figueras J, Steinberger JK, Krausmann F, Haberl H, Wiedmann T, Peters GP, Duro JA, Kastner T (2016) International inequality of environmental pressures: decomposition and comparative analysis. Ecol Indic 62:163–173

Seis M (2001) Confronting the Contradiction: Global Capitalism and Environmental Health. Int J Comp Sociol 42(1–2):123–144

Winans K, Kendall A, Deng H (2017) The history and current applications of the circular economy concept. Renew Sust Energ Rev 68:825–833

D’Amato D, Droste N, Allen B, Kettunen M, Lähtinen K, Korhonen J, Leskinen P, Matthies BD, Toppinen A (2017) Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. J Clean Prod 168:716–734

Twomey P, Washington H (2016) A future beyond growth: towards a steady state economy. Routledge

Suárez-Eiroa B, Fernández E, Méndez-Martínez G, Soto-Oñate D (2019) Operational principles of circular economy for sustainable development: linking theory and practice. J Clean Prod 214:952–961

D’Adamo I (2019) Adopting a circular economy: current practices and future perspectives. Soc Sci 8(12):328

Domenech T, Bahn-Walkowiak B (2019) Transition towards a resource efficient circular economy in Europe: policy lessons from the EU and the Member States. Ecol Econ 155:7–19

WEF (2020) The circular economy challenge. World Economic Forum

Desmond P, Asamba M (2019) Accelerating the transition to a circular economy in Africa

Dussaux D, Glachant M (2019) How much does recycling reduce imports? Evidence from metallic raw materials. Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy 8(2):128–146

Romero-Hernández O, Romero S (2018) Maximizing the value of waste: from waste management to the circular economy. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev 60(5):757–764

Failler P, Mohabeer R, Bragante D (2020) Regional action plan for the blue economy. 39p

Selosse S, Ricci O, Garabedian S, Maïzi N (2018) Exploring sustainable energy future in Reunion Island. Util Policy 55:158–166

Tahulela AC, Ballard HH (2020) Developing the circular economy in South Africa: challenges and opportunities. Sustainable Waste Management: Policies and Case Studies, 125–133

Boon EK, Anuga SW (2020) Circular Economy and its relevance for improving food and nutrition security in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of ghana. Mater Circ Econ 2(1):5

Charles RG, Davies ML, Douglas P, Hallin IL, Mabbett I (2019) Sustainable energy storage for solar home systems in rural Sub-Saharan Africa – a comparative examination of lifecycle aspects of battery technologies for circular economy, with emphasis on the South African context. Energy 166:1207–1215

Mativenga PT, Sultan AAM, Agwa-Ejon J, Mbohwa C (2017) Composites in a circular economy: a study of United Kingdom and South Africa. Procedia CIRP 61:691–696

Mutezo G, Mulopo J (2021) A review of Africa’s transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy using circular economy principles. Renew Sust Energ Rev 137:110609

EMF (2019) Circular economy systems diagram. Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Sihvonen S, Ritola T (2015) Conceptualizing ReX for aggregating end-of-life strategies in product development. Procedia CIRP 29:639–644

Kirchherr J, Reike D, Hekkert M (2017) Conceptualizing the circular economy: an analysis of 114 definitions. Resour Conserv Recycl 127:221–232

Mativenga PT, Agwa-Ejon J, Mbohwa C, Sultan AAM, Shuaib NA (2017) Circular economy ownership models: a view from South Africa Industry. Procedia Manufacturing 8:284–291

Maphosa V, Maphosa M (2020) E-waste management in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic literature review. Cogent Business & Management 7(1):1814503

Kowlesser P (2020) An overview of circular economy in Mauritius. In: Ghosh SK (ed) Circular Economy: Global Perspective. Springer, Singapore, pp 269–277

To LS, Seebaluck V, Leach M (2018) Future energy transitions for bagasse cogeneration: Lessons from multi-level and policy innovations in Mauritius. Energy Res Soc Sci 35:68–77

EMF (2015) Towards a circular economy: business rationale for an accelerated transition. Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Jiao W, Boons F (2014) Toward a research agenda for policy intervention and facilitation to enhance industrial symbiosis based on a comprehensive literature review. J Clean Prod 67:14–25

European Union (2008) Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives. L 312/3

Yoshida H, Shimamura K, Aizawa H (2007) 3R strategies for the establishment of an international sound material-cycle society. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 9(2):101–111

Potting J, Hekkert M, Worrell E, Hanemaaijer A (2017) Circular economy: measuring innovation in the product chain

WU Vienna (2019) Country profiles. Visualisations based upon the UN IRP Global Material Flows Database

Cornélus M, Pochat SL, Loisel M, Goethem MV (2016) Etude descriptive et opérationnelle sur l’économie circulaire à l’île de la Réunion – 2016. 70

FAO (2018) Fishery and aquaculture statistics

Breuil C, Yvergniaux Y (2017) Performances socio-économiques du secteur des pêches et de l’aquaculture dans l’espace COI

Richmond M (2016) Oil, gas and renewable energy: Western Indian Ocean, pp. 342–359

Alnuaim S Circular economy: a sustainability innovation and solution for oil, gas, and petrochemical industries

Kun H, Jian Z (2011) Circular economy strategies of oil and gas exploitation in China. Energy Procedia 5:2189–2194

World Bank (2016) Renewable energy consumption (% of total final energy consumption) - Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Cabo Verde, Comoros, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Sao Tome and Principe | Data

Morseletto P (2020) Restorative and regenerative: exploring the concepts in the circular economy. J Ind Ecol 24(4):763–773

Geng Y, Fu J, Sarkis J, Xue B (2012) Towards a national circular economy indicator system in China: an evaluation and critical analysis. J Clean Prod 23(1):216–224

World Bank (2018) What a waste: an updated look into the future of solid waste management. World Bank

Brink ten P, Kettunen M, Watkins E (2017) Expert group on green and circular economy in the outermost regions, 17

Ritchie H, Roser M (2018) Plastic pollution. Our World in Data

Reuters (2015) Eco-village promotes sustainability in Madagascar. News24. Online News Article. https://www.news24.com/news24/green/news/eco-village-promotes-sustainability-in-madagascar-20150323. Accessed November 2020

Ferrari K, Cerise S, Gamberini R, Lolli F An international partnership for the sustainable development of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. 5.

Lazare A, Devignes F, Enda E (2010) Etat des lieux du secteur informel de déchets en Afrique et dans les Caraïbes

Rocliffe S, Harris A (2014) Scaling success in octopus fisheries management in the Western Indian Ocean, 24

Rocliffe S, Peabody S, Samoilys M, Hawkins JP (2014) Towards a network of locally managed marine areas (LMMAs) in the Western Indian Ocean. PLoS One 9(7):e103000

SeyCCAT J (2016) Seychelles Marine Spatial Planning

Edwards Z, Sinan H (2020) State-led fisheries development: enabling access to resources and markets in the Maldives pole-and-line skipjack tuna fishery, in Securing sustainable small-scale fisheries: showcasing applied practices in value chains, post-harvest operations and trade, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

IOTC (2016) Resolution 16/01 on an interim plan for rebuilding the Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna stock in the iotc area of competence

SeyCCAT (2019) Seychelles launches World’s First Sovereign Blue Bond - SeyCCAT - The Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust

Childs J (2018) Extraction in four dimensions: time, space and the emerging geo(-)politics of deep-sea mining. Geopolitics:1–25

Availability of Data and Material

All data used were extracted from online databases and through a literature review.

Code Availability

Not applicable

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding from the Indian Ocean Commission which commissioned an analysis of the implementation of a circular economy in the 9 islands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by both authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M. Andriamahefazafy and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andriamahefazafy, M., Failler, P. Towards a Circular Economy for African Islands: an Analysis of Existing Baselines and Strategies. Circ.Econ.Sust. 2, 47–69 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00059-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00059-4