Abstract

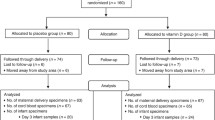

Vitamin D and calcium are essential micronutrients for reproductive success. Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of pregnancy complications including pre-eclampsia and preterm birth (PTB). However, inconsistencies in the literature reflect uncertainties regarding the true biological importance of vitamin D but may be explained by maternal calcium intakes. We aimed to determine whether low dietary consumption of calcium along with vitamin D deficiency had an additive effect on adverse pregnancy outcome by investigating placental morphogenesis and foetal growth in a mouse model. Female mice were randomly assigned to one of four diets: control-fed (+Ca+VD), reduced vitamin D only (+Ca−VD), reduced calcium only (−Ca+VD) and reduced calcium and vitamin D (−Ca−VD), and sacrificed at gestational day (GD) 18.5. Maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D3) levels were lower in each reduced diet group when compared with levels in +Ca+VD-fed mice. While the pregnancy rate did not differ between groups, in the −Ca−VD-fed group, 55% (5 out of 9 pregnant of known gestational age) gave birth preterm (<GD18.5). Of the −Ca−VD animals that gave birth at GD18.5, mean foetal weight increased by 8% when compared with +Ca+VD (P < 0.05) which was associated with increased placental efficiency (P = 0.05) as a result of changes to the placental labyrinth microstructure. In conclusion, we observed an interactive effect of low calcium and vitamin D intake that may impact offspring phenotype and preterm birth rate supporting the hypothesis that both calcium and vitamin D status are important for a successful pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Roberts CT. IFPA award in placentology lecture: complicated interactions between genes and the environment in placentation, pregnancy outcome and long term health. Placenta. 2010;31(Suppl):S47–53.

Cross JC. Formation of the placenta and extraembryonic membranes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:23–32.

Evans KN, Bulmer JN, Kilby MD, Hewison M. Vitamin D and placental-decidual function. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(5):263–71.

Wagner CL, Hollis BW. The implications of vitamin D status during pregnancy on mother and her developing child. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:500.

Shahbazi M, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Zareie M, Salek-Moghaddam A, Akhondi MM, Bahmanpoor M, et al. Expression profiling of vitamin D receptor in placenta, decidua and ovary of pregnant mice. Placenta. 2011;32(9):657–64.

Tesic D, Hawes JE, Zosky GR, Wyrwoll CS. Vitamin D deficiency in BALB/c mouse pregnancy increases placental transfer of glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2015;156(10):3673–9.

Wilson RL, Buckberry S, Spronk F, Laurence JA, Leemaqz S, O’Leary S, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene ablation in the conceptus has limited effects on placental morphology, function and pregnancy outcome. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131287.

Liu NQ, Ouyang Y, Bulut Y, Lagishetty V, Chan SY, Hollis BW, et al. Dietary vitamin D restriction in pregnant female mice is associated with maternal hypertension and altered placental and fetal development. Endocrinology. 2013;154(7):2270–80.

Lehmann B. The vitamin D3 pathway in human skin and its role for regulation of biological processes. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81(6):1246–51.

Holick MF. Vitamin D: a D-Lightful health perspective. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(10 Suppl 2):S182–94.

Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D and pregnancy: skeletal effects, nonskeletal effects, and birth outcomes. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92(2):128–39.

Lerchbaum E, Obermayer-Pietsch B. Vitamin D and fertility: a systematic review. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2012;166(5):765–78.

Aghajafari F, Nagulesapillai T, Ronksley PE, Tough SC, O’Beirne M, Rabi DM. Association between maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:f1169.

Wei SQ, Qi HP, Luo ZC, Fraser WD. Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2013;26(9):889–99.

Liu NQ, Hewison M. Vitamin D, the placenta and pregnancy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523(1):37–47.

Kumar R, Cohen WR, Silva P, Epstein FH. Elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D plasma levels in normal human pregnancy and lactation. J Clin Invest. 1979;63(2):342–4.

Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double-blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26(10):2341–57.

Weisman Y, Harell A, Edelstein S, David M, Spirer Z, Golander A. 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in vitro synthesis by human decidua and placenta. Nature. 1979;281(5729):317–9.

Novakovic B, Sibson M, Ng HK, Manuelpillai U, Rakyan V, Down T, et al. Placenta-specific methylation of the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene: implications for feedback autoregulation of active vitamin D levels at the fetomaternal interface. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(22):14838–48.

Kovacs CS. Maternal mineral and bone metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(2):449–547.

Hawes JE, Tesic D, Whitehouse AJ, Zosky GR, Smith JT, Wyrwoll CS. Maternal vitamin D deficiency alters fetal brain development in the BALB/c mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2015;286:192–200.

Bergel E, Belizan JM. A deficient maternal calcium intake during pregnancy increases blood pressure of the offspring in adult rats. BJOG. 2002;109(5):540–5.

Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123(11):1939–51.

Goldstein DA. Serum Calcium. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical methods: the history, physical and laboratory examinations. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. p. 677–9.

Quimby FW, Luong RH. Clinical chemistry of the laboratory mouse. In: Fox JG, Barthold SW, Davisson MT, Newcomer CE, Quimby FW, Smith AL, eds. The mouse in biomedical research. Vol 3. 2nd ed. MA, USA: Elsevier; 2007:181.

Roberts CT, White CA, Wiemer NG, Ramsay A, Robertson SA. Altered placental development in interleukin-10 null mutant mice. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl A):S94–9.

Wilson RL, Leemaqz SY, Goh Z, McAninch D, Jankovic-Karasoulos T, Leghi GE, et al. Zinc is a critical regulator of placental morphogenesis and maternal hemodynamics during pregnancy in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15137.

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011.

Prietl B, Treiber G, Pieber TR, Amrein K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients. 2013;5(7):2502–21.

Reynolds LP, Caton JS, Redmer DA, Grazul-Bilska AT, Vonnahme KA, Borowicz PP, et al. Evidence for altered placental blood flow and vascularity in compromised pregnancies. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):51–8.

Johnson LE, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D receptor null mutant mice fed high levels of calcium are fertile. J Nutr. 2001;131(6):1787–91.

Baker AM, Haeri S, Camargo CA Jr, Stuebe AM, Boggess KA. A nested case-control study of first-trimester maternal vitamin D status and risk for spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28(9):667–72.

Shand AW, Nassar N, Von Dadelszen P, Innis SM, Green TJ. Maternal vitamin D status in pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a group at high risk for pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2010;117(13):1593–8.

Dunlop AL, Taylor RN, Tangpricha V, Fortunato S, Menon R. Maternal micronutrient status and preterm versus term birth for black and white US women. Reprod Sci. 2012;19(9):939–48.

Fernandez-Alonso AM, Dionis-Sanchez EC, Chedraui P, et al. First-trimester maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) status and pregnancy outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;116(1):6–9.

Perez-Ferre N, Torrejon MJ, Fuentes M, Fernandez MD, Ramos A, Bordiu E, et al. Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in pregnancy with glucose homeostasis and obstetric and newborn outcomes. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(5):676–84.

Fowden AL, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Coan PM, Constancia M, Burton GJ. Placental efficiency and adaptation: endocrine regulation. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 14):3459–72.

Coan PM, Vaughan OR, Sekita Y, Finn SL, Burton GJ, Constancia M, et al. Adaptations in placental phenotype support fetal growth during undernutrition of pregnant mice. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 3):527–38.

Constancia M, Angiolini E, Sandovici I, et al. Adaptation of nutrient supply to fetal demand in the mouse involves interaction between the Igf2 gene and placental transporter systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(52):19219–24.

Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL, Carlquist JF, et al. Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(7):963–8.

Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Tworoger SS, Willett WC, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1063–9.

Dora KA, Doyle MP, Duling BR. Elevation of intracellular calcium in smooth muscle causes endothelial cell generation of NO in arterioles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(12):6529–34.

Vallotton M. The renin-angiotensin system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1987;8(2):69–74.

Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science (New York, NY). 2014;345(6198):760–5.

Mor G, Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(6):425–33.

Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C. An innate view of human pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1999;20(3):114–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebecca Sawyer for conducting the serum assays, Gary Heinemann and Dylan McCullough for assistance with animal and laboratory work.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) awarded to CTR and PHA (GNT1020754). CTR was supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (GNT1020749) and currently supported by the Lloyd Cox Professorial Research Fellowship, University of Adelaide. PHA is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Award (GNT1051858). RLW and JAL were recipients of Australian Postgraduate Awards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, R.L., Phillips, J.A., Bianco-Miotto, T. et al. Reduced Dietary Calcium and Vitamin D Results in Preterm Birth and Altered Placental Morphogenesis in Mice During Pregnancy. Reprod. Sci. 27, 1330–1339 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-019-00116-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-019-00116-2