Abstract

Redox fields observed near contaminated sites are related to electrochemical and electrobiological reactions. The term biogeobattery is used to describe the redox processes in underground organic contaminated sites which are biogeochemical systems, where bacteria, conductive minerals, oxygen, and organic contaminants create numerous anode–cathode pairs by transferring electrons from reducing areas under the water table or other anaerobic conditions to oxidizing areas above the water table. A numerical biogeobattery model established based on the geobattery and inert electrode model is the theoretical basis for numerical modeling. A coupled method of tetrahedral finite elements and hexahedral infinite elements is proposed for the algorithm basis of numerical modeling. Then a small-scale biogeochemical system and a field-scale landfill system are modeled using the numerical biogeobattery model and the finite–infinite element coupling method. The results suggest that the accuracy of the coupled method is superior to the finite element method. The amplitude change in the embedded redox field has a great effect on self-potential anomalies, while the gradient change in the embedded redox field has no significant impact on self-potential anomalies. The resolution of the surface self-potential decreases with the depth of biogeochemical systems. The biogeobattery model based on the inert electrode model is an effective numerical model in biogeochemical systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

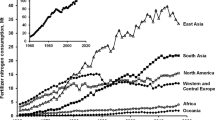

The self-potential (SP) method uses electric potential anomalies measured by nonpolarizing electrodes at the Earth’s surface or in wells to recognize geological, hydrological, biological, and chemical targets [1, 2]. As a passive source method, it is very efficient by getting rid of power supply. Mohd [3] measured the SP data in downhole to enhance the oil recovery monitoring. Safipour [4] studied an SP investigation to explore submarine massive sulfides. Zlotnicki [5] used the SP method to study volcano activities. Chen [6] used the SP skewness and kurtosis to forecast the earthquake. Roubinet [7] modeled SP signals in fractured rock to identify hydraulically active fractures. Ikard [8] studied the surface–groundwater exchange by a floating SP dipole. Ahmed [9] implemented the joint inversion of hydraulic head and SP data associated with harmonic pumping tests. Because of its characteristics, the SP method is supposed to be applied to long-term monitoring of organic-rich contaminated sites or methods of remediation. Naudet [10, 11] and Revil [12] applied it to describe the redox front of contaminated sites. Arora [13] and Gallas [14] successfully monitored the leakage of landfills using this method. Martínez-Pagán [15] simulated the contamination diffusion process through laboratory experiments and verified the feasibility of this method to monitor contamination. Placencia-Gomez [16] took it to investigate the leakage of tailing ponds. Also, Che-Alota [17] and Forte [18] used it to monitor the degradation of hydrocarbon contaminants in the environment. Rittgers [19] studied SP signals generated by the corrosion of buried metallic objects to explain the physical and chemical mechanisms of such electrical signals. Giampaolo [20] performed the monitoring of a crude oil-contaminated site using the SP method. Mao [21] studied the SP tomography by sandbox and field experiments and applied it to groundwater remediation and contaminant plumes. Abbas [22] analyzed the redox field distribution of an organic-rich contaminated site obtained by the inversion of SP data. Cui [23, 24] conducted the sandbox experiments to try to use the SP method to monitor the diffusion and migration of underground contamination. Graham [25] discussed the SP as a predictor of seawater intrusion in coastal groundwater boreholes. Fernandez [26] assessed whether combining electrical resistivity and SP measurements can map the zones affected by anaerobic degradation. These studies show that the laboratory or field observation of the SP method is fast and nondestructive, has no secondary pollution, has real-time monitoring, and is of low cost. And the SP method is sensitive to many kinds of signals associated with contaminant diffusion, such as seepage, redox processes, and microbial activities, which is applicable to the field of biogeophysical exploration, especially the detection and monitoring of underground organic contaminants.

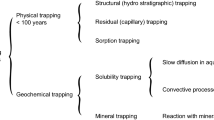

There are two main contributions of measured SP data, namely the streaming potential associated with pore water flow or geothermal systems in saturated and unsaturated regions and the redox potential associated with redox processes of orebodies or organic contaminants. In environmental contamination investigations, abnormal redox potential gradients on the ground help determine the location of contaminants. Microorganisms (or bacteria) are believed to be responsible for these redox processes in contaminant plumes [10,11,12,13, 27,28,29,30,31], where every element of the redox interface (e.g., the water table) behaves like a dipole with cathodic half-cell reactions occurring at the upper, more oxidizing end, and anodic half-cell reactions at the lower, more reducing end [13]. Microorganisms support the migration of electrons which flow from the anode through the electrical circuit toward a terminal redox electron acceptor at the cathode [12]. Sato and Mooney [2] first attempted to construct a galvanic cell model to evaluate redox fields for the application of the SP method in mineral exploration. Krauskopf [32] studied the formula for the SP generated by redox reactions. The inert electrode model (IEM) proposed by Stoll [33] and Bigalke [34] is the formulation that takes into account the subsurface redox conditions and provides a mathematical basis for calculating the theoretical redox field of minerals. Mendonça [35] conducted 2D forward and inversion studies of mineral redox potential based on the IEM. Castermant [36] calculated the distribution of the SP generated by redox reactions during underground metal corrosion. Mohamad Sadegh and Ali [37, 38] carried out the forward modeling and physical experiments of the SP based on geobattery models, and successfully inverted experimental observation data. Targeted numerical modeling of the redox processes is helpful to identify the characteristics of the SP anomalies caused by microbial degradation of organic contaminants. Accordingly, it can provide a forward algorithm and numerical foundation for applying the SP method in environmental contamination fields. In order to improve the calculation accuracy of numerical modeling, the Astley uni-directional mapping infinite element is introduced to realize an effective coupling of tetrahedral finite elements and hexahedral infinite elements in spacial and physical properties. Then based on theories of the geobattery and the IEM which provides a consistent electrochemical model and the SP fields from a set of current sources, a numerical biogeobattery model is established for the three-dimensional (3D) numerical modeling of redox potentials from the microbial degradation of organic contaminants.

2 Numerical biogeobattery model

2.1 Geobattery

In mineral exploration, the subsurface redox process is characterized by negative SP anomalies on the ground [39,40,41]. The main reason for the formation of orebody redox fields is the penetration of rainwater and the diffusion of oxygen, which forms an oxidizing environment in the shallow layer and a reducing environment in the deep. The orebody connects the shallow and deep regions, causing electrons to flow upward [35]. As a result, the upper part releases electrons to form the cathode of a battery and the lower part acquires electrons to form the anode. “Geobattery” is used to describe this system [2, 12, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 42].

2.2 Biogeobattery

The term “biogeobattery” coined by Revil and his coworkers [10,11,12, 29] is used to describe the electron-transfer mechanism of a biogeochemical system which is an interdisciplinary system of geophysics, geochemistry, and microbiology. Revil [12] proposed a biogeobattery linear model to explain the redox fields of thin, flat, and contaminated aquifers. Hubbard [43] and Fachin [44] studied the SP data from an analog biogeobattery model through experiments. Also, Risgaard-Petersen [45] measured the electric fields generated in a biogeobattery model with microelectrodes.

In a biogeobattery system, the growth of bacterial colonies is associated with organic contaminants and oxygen levels. Therefore, those bacteria that can participate in the degradation of underground organic contaminants and produce redox processes are likely to be confined to the water table, where contaminated water mixes with oxygen-rich meteoric water [12, 13]. The electron-transfer mechanism can be summarized into three categories: (1) The first mechanism (named model I, see Fig. 1a) shows that conductive minerals and the bacteria are found near the water table [12, 13, 46,47,48]; (2) the second mechanism (named model II, see Fig. 1b) suggests that different bacterial populations form nanowire networks by conductive pili [49,50,51]; (3) the third mechanism (named model III, see Fig. 1c) shows that the filamentous bacteria can also transfer electrons alone [52].

Sketches of three electron-transfer mechanisms in a biogeochemical system. a In model I, bacteria and (semi-) conductive minerals facilitate the transfer of electrons. b In model II, bacterial colonies form nanowire networks by conductive pili. c In model III, electrons transfer from donors to acceptors through insulated internal wires of filamentous bacteria. d Illustration of a biogeochemical system from microbial degradation of organic contaminants. e Illustration of an equivalent circuit of a biogeochemical system. Modified from [11, 12, 44, 52]

2.3 Numerical biogeobattery model from IEM

All above-mentioned electron-transfer mechanisms shown in Fig. 1 are not isolated. As shown in Fig. 1d, a biogeochemical system in which the electron-transfer mechanism may contain one or two, even three mechanisms simultaneously can be simplified into an equivalent circuit, as shown in Fig. 1e. Based on the above discussion, a macroscopic numerical biogeobattery model is established where the model space is constrained by defining interfaces (e.g., the water table) and the thin, flat distribution of primary redox fields [12, 13, 22, 29]. Then the forward modeling of the numerical biogeobattery model can be realized through the IEM.

Numerical modeling of a biogeobattery model can be realized by solving the governing differential equation with numerical methods. The large sparse system of linear equations can be expressed as

where K is the n × n stiffness matrix which is obtained by the finite–infinite element coupling method in this paper, u is an n-dimensional vector with potential values that are unknown and need to be solved, q is an n-dimensional source vector, and n is the number of nodes.

Then, the kth value uk of u can be expressed as

where \({\mathbf{r}}_{k}^{T}\) is the kth row of the matrix K−1, K−1 represents the inverse matrix of K.

The distribution of redox fields and current source densities is assumed to be situated at the thin, flat biogeobattery system which is near the water table and can be regarded as numerous micro-geobatteries (or dipoles) [12, 13, 22, 29]. Then current source intensities can be evaluated by the IEM approximately. The current term qi can be expressed as [34, 35]

where i represents the ith node of the biogeobattery, Ec represents the electrode potential (V), Eh,i represents the redox potential (V), ui is the electric potential (V), and Si represents the electrical conductance (S).

Biogeobattery nodes with index i ≡ i(α), α = 1,…, N are assigned. Substitution of Eq. (2) into Eq. (3) gives

where Ri≡ 1/Si can be regarded as the electrical resistance (Ω).

The charge conservation condition is taken as the N + 1th equation, and then the matrix form of Eq. (4) can be written as

where ri, j is the jth entry of vector ri, i and j represent the nodeID of biogeobattery nodes. Solve Eq. (5) and then get the unknown currents qi in the biogeochemical system.

3 Finite–infinite element coupling method

3.1 Boundary value problem

The Poisson equation in a biogeobattery model can be expressed as

where σ is the electric conductivity, δ(Ai) represents the Dirac delta function of point Ai.

On the air–Earth interface, electric potentials satisfy

On the infinite boundary, the coupling of finite elements and infinite elements is achieved.

3.2 Infinite element

Ungless first proposed the concept of the infinite element [53]. The infinite elements are generally grouped into three types: Astley-mapping infinite elements [54, 55], Bettess mapping infinite elements [56, 57], and Burnett multipole expansion infinite elements [58, 59]. Compared with finite elements, infinite elements are more suitable for solving infinite region problems. The essence of infinite elements is an extension of finite elements in infinite domain or semi-infinite domain problems. Infinite elements can be introduced to couple with finite elements at model boundaries to deal with truncated boundary problems. The finite–infinite element coupling method has also been successfully applied to the direct current resistivity method [60, 61], the electromagnetic method [62, 63], and other geophysical fields.

The coupled relationship between finite elements and the Astley-mapping infinite elements [54, 55] is shown in Fig. 2. The infinite elements have directionalities which take the point M at the center of the ground as the only starting point of the mapping and radially map to infinity through the boundary nodes of the finite elements.

As shown in Fig. 3, the uni-directional infinite element starts from nodes 1, 2, 3, and 4 then passes through the middle nodes 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively, to infinity. The attenuation degree of the SP in the infinite element can be controlled by the distance from M to the surface S5678. Meanwhile, the electric potential values of the four nodes at infinity are zero, which are not considered.

The positive direction of ξ points to infinity, and spatial coordinates of any point in infinite elements can be expressed as

where ξ, η, and ζ are local coordinates in parent elements, x1, x2,…, x8, y1, y2,…, y8, and z1, z2,…, z8 are spatial coordinates of infinite element nodes, Mi (ξ, η, ζ) represents the mapping function which can be expressed as

The SP value of any point in infinite elements can be expressed as

where Ni is the shape function which satisfies

3.3 Infinite element analysis

In finite elements, the Jacobi matrix is calculated by the shape function, while the Jacobi matrix in infinite elements is calculated by the mapping function, which can be expressed as

Let ∂Ni/∂x = Fix, ∂Ni/∂y = Fiy, and ∂Ni/∂z = Fiz, then the stiffness matrix of any infinite element can be expressed as

where i, j = 1,…, 8, and Kij represent the stiffness value of infinite elements.

3.4 Finite–infinite element coupling

As shown in Fig. 4, in order to fit complex terrains better, all hexahedral finite elements are further subdivided into tetrahedral finite elements. The stiffness matrix of every finite element and infinite element is n × n dimensional, where n is the number of element nodes and it is 4 and 8 in tetrahedral finite elements and hexahedral infinite elements, respectively. In the coupled process, just the stiffness matrix values calculated by finite elements and infinite elements are added to the corresponding position of the total stiffness matrix according to the nodeID, respectively.

where Kij represents the stiffness value of the coupled method, K 1ij is the stiffness value of finite elements, K 2ij is the stiffness value of infinite elements, and i and j are nodeID.

4 Numerical modeling

4.1 Algorithm validation

The correctness and effectiveness of the coupled method are verified by a point source model (see Fig. 5) in homogeneous half-space. In this validation model, the finite element region with dimensions (length × width × height) of 15 m × 15 m × 10 m is subdivided into 30 × 30 × 20 hexahedral elements, the background resistivity is 100 Ω-m, and the point source with 1 amp is at the surface center. The accuracy of the coupled method with different infinite element dimensions in the mapping direction is also discussed. As shown in Fig. 6, when the term “Multiple,” which means the multiple of the infinite element dimension in the mapping direction to the distance from the mapping origin M to the boundary of the finite element region, is 2.5, the minimum mean-square error (MSE) is 0.0292 (see Fig. 6a). The result of the ground SP curves (see Figs. 6b–c) shows that the accuracy of the coupled method is better than the traditional finite element method with the mixed boundary condition (MSE = 0.3158) or the Dirichlet boundary condition (MSE = 3.2570) under the same subdivision conditions, and the results of the coupled method coincide exactly with the analytical solution. The “Multiple” is set as 2.5 in the following models.

Algorithm validation of the coupled method. a Accuracy of the coupled method with different infinite element dimensions, where the term “Multiple” means the multiple of the infinite element dimension in the mapping direction to the distance from the mapping origin M to the boundary of the finite element region; b Electrical potential curves of different conditions, where the “Multiple” is 2.5; c The relative error of the three conditions to the analytical solution, where the “Multiple” is 2.5

4.2 Test—variable redox decay of biogeobattery

The 2D cross-sectional structure of the 3D geoelectric model is shown in Fig. 7. The resistivity (100 Ω-m) model has dimensions of 5 m × 5 m × 5 m. A thin, flat biogeobattery system (10 Ω-m) with dimensions of 3 m × 3 m × 0.2 m is embedded into this model. The water table is at a depth of 0.5 m, and presupposed four redox fields shown in Fig. 7 are embedded into the biogeobattery to evaluate the dependence of SP anomalies on redox fields. The redox potentials A–D shown in Fig. 7 start from 50 mV at a depth of 0.4 m and decrease to preset values at a depth of 0.6 m, which are − 50, − 50, 0, and 20 mV, respectively [35]. Assume that Ri equals to zero.

The numerical results (see Fig. 8) show that in cases A and B, larger SP anomalies obtained from higher redox amplitudes are observed. Correspondingly, smaller SP anomalies are obtained in cases C and D. There is an important conclusion that the gradient change in the embedded redox field has no obvious effect on SP anomalies, which is of great significance on field measurements of primary redox fields in contaminated sites.

4.3 Small-scale biogeobattery system

In a small-scale biogeobattery system, the microcolonies are distributed regionally. So, they can be considered as individual biogeobatteries. As shown in Fig. 9, a small-scale (0.1 m × 0.1 m) model with three microcolonies is modeled to explore the SP anomalies of micro-biogeobatteries. As discussed in the Test part, for SP anomalies, the gradient change in redox potentials is negligible. So, the numerical model can be simplified by only considering the redox potential values at the cathode interface and anode interface. Here, they are set as 10 mV and − 10 mV, respectively. When the microcolonies are at a shallow depth (see Fig. 10a), the ground SP anomalies can distinguish the distributions and even the geometries of these individual biogeochemical systems easily. As the depth increases, the ground SP anomalies gradually become blurred and finally present a regional negative anomaly (see Figs. 10b–c), while in a field-scale biogeochemical system, the water table is usually located at a depth of decimeters or even meters. Thus, the ground SP anomaly in field is a macroscopic response of the whole system.

4.4 Field-scale landfill model

In a field-scale biogeochemical system, the water table with rich organic matters and dissolved oxygen can be considered as a thin, flat macro-biogeobattery model. The system usually exists in landfills, where microbial activities drive electrochemical reactions and establish electron-transfer structures through nanowire networks, microorganisms and (semi-) conductive minerals, or filamentous bacteria. These mechanisms can connect the cathode and anode of a field-scale biogeobattery quickly and facilitate the transfer of electrons in separated space, which also means that the resistance parameter is very small in a biogeochemical system.

A landfill model (see Fig. 11) with complex terrains has dimensions of 100 m × 100 m × 50 m, where the biogeobattery space with dimensions of 32 m × 32 m × 1 m is constrained by defining the water table and a thin, flat distribution of redox fields. For the thickness of each layer and its resistivity value (see Fig. 11), refer to Naudet [11]. Here, the redox potential values at the cathode interface and the anode interface are set as 300 mV and − 300 mV, respectively. Ri equals to 1 Ω. The result (see Fig. 12) suggests that the landfill model with a biogeochemical system has obvious negative SP anomalies on the ground surface.

5 Discussion

In this paper, a numerical biogeobattery model and a new numerical modeling method based on the IEM and the finite–infinite element coupling, respectively, are presented to simplify the evaluation of SP anomalies from biogeochemical systems which may easily occur in environments with rich organic matters and an oxidation–reduction interface such as marine sedimentary environments and underground contaminated sites. The numerical examples provide the foundation of data inversion and interpretation in environmental contamination problems like microbial degradation of underground organic contaminants and help to promote the application effect of the SP method in underground contamination detection and monitoring. The numerical result of the effect of preset redox fields and its gradient changes on the ground SP anomaly in the Test part is the same with the work of Mendonça [35], and it provides numerical support and help to simplify the measurement work. The small-scale biogeobattery model and the field-scale landfill model show the negative SP anomaly on the ground, which is consistent with the field work of Naudet [10, 11, 30], Revil [12], Arora [13], Abbas [22], and Linde [29]. The SP surveying is a promising method for environmental problems and can be applied to laboratory experiments or field work relating to 3D time-lapse (4D) monitoring of underground contaminants.

6 Conclusion

The numerical modeling results of the Algorithm Validation and the Test part suggest that (1) the coupled method has high precision, easy implementation, and good processing effects on truncation boundary problems; (2) at least for these models considered here, the preset redox field amplitude is an important factor affecting ground SP anomalies; (3) however, the gradient change in the embedded redox field has no significant effect on ground SP anomalies, which is the foundation of considering a thin, flat IEM as a biogeobattery model. The numerical results in the small-scale biogeochemical system and the field-scale landfill model further show that the biogeobattery model from the IEM is an effective numerical model in biogeochemical systems.

References

Corwin RF (1990) The self-potential method for environmental and engineering applications. Geotech Environ Geophys 1:127–145

Sato M, Mooney HM (1960) Electrochemical mechanism of sulfide self-potentials. Geophysics 25(1):226–249

Mohd TAT, Jaafar MZ, Ali Rasol AA, Hamid MF (2017) Measurement of streaming potential in downhole application: an insight for enhanced oil recovery monitoring. MATEC Web Conf 87(03002):1–8

Safipour R, Hölz S, Halbach J, Jegen M, Petersen S, Swidinsky A (2017) A self-potential investigation of submarine massive sulfides: palinuro Seamount. Tyrrhenian Sea. Geophys 82(6):A51–A56

Zlotnicki J, Vargemezis G, Johnston MJS, Sasai Y, Reniva P, Alanis P (2017) Very-low-frequency resistivity, self-potential and ground temperature surveys on Taal volcano (Philippines): implications for future activity. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 340:180–197

Chen HJ, Chen CC, Ouillon G, Sornette D (2017) Using geoelectric field skewness and kurtosis to forecast the 2016/2/6, M L 6.6 Meinong, Taiwan Earthquake. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci 28(5):745–761

Roubinet D, Linde N, Jougnot D, Irving J (2016) Streaming potential modeling in fractured rock: insights into the identification of hydraulically active fractures. Geophys Res Lett 43:4937–4944

Ikard SJ, Teeple AP, Payne JD, Stanton GP, Banta JR (2018) New insights on scale-dependent surface-groundwater exchange from a floating self-potential dipole. J Environ Eng Geophys 23(2):261–287

Ahmed AS, Jardani A, Revil A, Dupont JP (2016) Joint inversion of hydraulic head and self-potential data associated with harmonic pumping tests. Water Resour Res 52(9):6769–6791

Naudet V, Revil A, Bottero JY (2003) Relationship between self-potential (SP) signals and redox conditions in contaminated groundwater. Geophys Res Lett 30(21):1–4

Naudet V, Revil A, Rizzo E, Bottero JY, Begassat P (2004) Groundwater redox conditions and conductivity in a contaminant plume from geoelectrical investigations. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 8(1):8–22

Revil A, Mendonça CA, Atekwana EA, Kulessa B, Hubbard SS, Bohlen KJ (2010) Understanding biogeobatteries: where geophysics meets microbiology. J Geophys Res 115(G1):1–22

Arora T, Linde N, Revil A, Castermant J (2007) Non-intrusive characterization of the redox potential of landfill leachate plumes from self-potential data. J Contam Hydrol 92(3):274–292

Gallas JDF, Fabio Taioli, Filho WM (2011) Induced polarization, resistivity and self-potential: a case history of contamination evaluation due to landfill leakage. Environ Earth Sci 63(2):251–261

Martínez-Pagán P, Jardani A, Revil A, Haas A (2010) Self-potential monitoring of a salt plume. Geophysics 75(4):17–25

Placencia-Gomez E, Parviainen A, Hokkanen T, Loukola-Ruskeeniemi K (2010) Integrated geophysical and geochemical study on AMD generation at the Haveri Au-Cu mine tailings. SW Finl Environ Earth Sci 61(7):1435–1447

Che-Alota V, Atekwana Estella A, Atekwana Eliot A, Sauck William A, Werkema DD Jr (2009) Temporal geophysical signatures from contaminant-mass remediation. Geophysics 74(4):B113–B123

Forte SA, Bentley LR (2013) Mapping Degrading Hydrocarbon Plumes with Self Potentials: investigation on Causative Mechanisms using Field and Modeling Data. J Environ Eng Geophys 18(1):27–42

Rittgers JB, Revil A, Karaoulis M, Mooney MA, Slater LD, Atekwana EA (2013) Self-potential signals generated by the corrosion of buried metallic objects with application to contaminant plumes. Geophysics 78(5):EN65–EN82

Giampaolo V, Rizzo E, Titov K, Konosavsky PK, Laletina D, Maineult A, Lapenna V (2014) Self-potential monitoring of a crude oil-contaminated site (Trecate, Italy). Environ Sci Pollut Res 21(15):8932–8947

Mao D, Revil A, Hort RD, Munakata-Marr J, Atekwana EA, Kulessa B (2015) Resistivity and self-potential tomography applied to groundwater remediation and contaminant plumes: sandbox and field experiments. J Hydrol 530:1–14

Abbas M, Jardani A, Soueid Ahmed A, Revil A, Brigaud L, Begassat P, Dupont JP (2017) Redox potential distribution of an organic-rich contaminated site obtained by the inversion of self-potential data. J Hydrol 554:111–127

Yi-an Cui, Liu LB, Zhu XX (2017) Unscented Kalman filter assimilation of time-lapse self-potential data for monitoring solute transport. J Geophys Eng 14:920–929

Yi-an Cui, Wei WS, Zhu XX, Liu JX (2017) Time-lapse inversion of self-potential data using Kalman filter. Chin J Geophys 60(8):3246–3253 (in Chinese)

Graham MT, MacAllister DJ, Jackson M, Vinogradov J, Butler AP (2018) Self-Potential as a predictor of seawater intrusion in coastal groundwater boreholes. Water Resour Res 54:6055–6071

Fernandez PM, Bloem E, Binley A, Philippe RSBA, French HK (2019) Monitoring redox sensitive conditions at the groundwater interface using electrical resistivity and self-potential. J Contam Hydrol 226(103517):1–12

Christensen TH, Bjerg PL, Banwart SA, Jakobsen R, Heron G, Albrechtsen HJ (2000) Characterization of redox conditions in groundwater contaminant plumes. J Contam Hydrol 45(3–4):165–241

Christensen TH, Kjeldsen P, Bjerg PL, Jensen DL, Christensen JB, Baun A, Albrechtsen HJ, Heron G (2001) Biogeochemistry of landfill leachate plumes. Appl Geochem 16(7–8):659–718

Linde N, Revil A (2007) Inverting self-potential data for redox potentials of contaminant plumes. Geophys Res Lett 34(14):1–5

Naudet V, Revil A (2005) A sandbox experiment to investigate bacteria-mediated redox processes on self-potential signals. Geophys Res Lett 34(L11405):1–4

Vichabian Y, Reppert P, Morgan FD (1999) [Environment and engineering geophysical society symposium on the application of geophysics to engineering and environmental problems 1999-,] Symposium on the application of geophysics to engineering and environmental problems. Self potential mapping of contaminants, pp 657–662

Krauskopf KB, Bird DK (1995) Introduction to geochemistry, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill International Editions, New York. https://doi.org/10.1029/96eo00064

Stoll J, Bigalke J, Grabner EW (1995) Electrochemical modeling of self-potential anomalies. Surv Geophy 16:107–120

Bigalke J, Grabner EW (1997) The geobattery model: a contribution to large scale electrochemistry. Electrochim Acta 42(23–24):3443–3452

Mendonça CA (2008) Forward and inverse self-potential modeling in mineral exploration. Geophysics 73(1):F33–F43

Castermant J, Mendonça CA, Revil A, Trolard F, Bourrié G, Linde N (2008) Redox potential distribution inferred from self-potential measurements associated with the corrosion of a burden metallic body. Geophys Prospect 56(2):269–282

Mohamad Sadegh R, Ali B (2013) Forward modeling and inversion of self-potential anomalies caused by 2D inclined sheets. Explor Geophys 44(3):176–184

Mohamad Sadegh R, Ali B (2015) Laboratory modelling of self-potential anomalies due to spherical bodies. Explor Geophys 46(4):320–331

Corry CE (1985) Spontaneous polarization associated with porphyry sulfide mineralization. Geophysics 50:1020–1034

Gay SP (1967) A 1800 millivolt self-potential anomaly near Hualgayoc, Peru. Geophys Prospect 15(2):236–245

Goldie M (2002) Self-potentials associated with the Yanacocha high-sulfidation gold deposit in Peru. Geophysics 67(3):684–689

Sivenas P, Beales FW (1982) Natural geobatteries associated with sulphide ore deposits, 1- Theoretical studies. J Geochem Explor 17:123–143

Hubbard CG, West LJ, Morris K, Kulessa B, Brookshaw D, Lloyd JR, Shaw S (2011) In search of experimental evidence for the biogeobattery. J Geophys Res 116(G04018):1–11

Fachin SJS, Abreu EL, Mendonça CA, Revil A, Novaes GC, Vasconcelos SS (2012) Self-potential signals from an analog biogeobattery model. Geophysics 77(4):EN29–EN37

Risgaard-Petersen N, Damgaard LR, Revil A, Nielsen LP (2014) Mapping electron sources and sinks in a marine biogeobattery. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 119(8):1475–1486

Kato S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe K (2012) Microbial interspecies electron transfer via electric currents through conductive minerals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(25):10042–10046

Nielsen L, Risgaard-Petersen N, Fossing H, Christensen P, Sayama M (2010) Electric currents couple spatially separated biogeochemical processes in marine sediment. Nature 463:1071–1074

Summers ZM, Fogarty HE, Leang C, Franks AE, Malvankar NS, Lovley DR (2010) Direct exchange of electrons within aggregates of an evolved syntrophic coculture of anaerobic bacteria. Science 330(6009):1413–1415

Dubey GP, Ben-Yehuda S (2011) Intercellular nanotubes mediate bacterial communication. Cell 144:590–600

Gorby YA, Yanina Svetlana, Mclean Jeffrey S, Rosso Kevin M et al (2006) Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(30):11358–11363

Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Mehta T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MS, Lovley DR (2005) Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435:1098–1101

Pfeffer C, Larsen S, Song J, Dong M, Besenbacher F, Meyer RL, Kjeldsen KU, Schreiber L, Gorby YA, El-Naggar MY (2012) Filamentous bacteria transport electrons over centimetre distances. Nature 491(7432):218–221

Ungless RF (1973) An infinite element. M.S. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

Astley RJ, Macaulay GJ, Coyette JP (1994) Mapped wave envelope elements for acoustical radiation and scattering. J Sound Vib 170(1):97–118

Astley RJ, Macaulay GJ, Coyette JP et al (1998) Three-dimensional wave-envelope elements of variable order for acoustic radiation and scattering, Part I, Formulation in the frequency domain. J Acoust Soc Am 103(1):49–63

Zienkiewicz OC, Bettess P (1977) Diffraction and refraction of surface wave suing finite and infinite elements. Int J Numer Methods Eng 13(11):1271–1290

Zienkiewicz OC, Bando K, Bettess P et al (1985) Mapped Infinite element for exterior wave problems. Int J Numer Methods Eng 21(7):1229–1251

Burnett DS (1994) A three-dimensional acoustic infinite element based on a prolate spheroidal multipole expansion. J Acoust Soc Am 96(5):2798–2816

Burnett DS, Holford RL (1998) Prolate and oblate spheroidal acoustic infinite elements. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 158(1–2):117–141

Xiao X, Yuan Y, Tang JT (2014) 2.5D DC resistivity forward modeling by finite-infinite element coupling method. J Cent South Univ (Sci Technol) 45(8):2691–2700 (in Chinese)

Yuan Y, Qiang JK, Tang JT, Ren ZR, Xiao X (2016) 2.5D direct-current resistivity forward modeling and inversion by finite-element-infinite-element coupled method. Geophys Prospect 64(3):767–779

Tang JT, Zhang LC, Gong JZ, Xiao X (2014) frequency domain-controlled source electromagnetic numerical modeling with coupled finite-infinite element method. J Cent South Univ (Sci Technol) 45(4):1251–1260 (in Chinese)

Zhang LC, Tang JT, Ren ZY, Xiao X (2017) Forward modeling of 3D CSEM with the coupled finite-infinite element method based on the second field. Chin J Geophys 60(9):3655–3666 (in Chinese)

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 41874145);and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant Number 2018JJ2499).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, J., Cui, Ya., Zhang, L. et al. Numerical modeling of biogeobattery system from microbial degradation of underground organic contaminant. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 208 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2008-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2008-9