Abstract

In this work, different approaches to fibre-metal laminates modelling are presented. Micromechanical, mesomechanical and macromechanical models are discussed. The application of these approaches for exemplary fibre-metal laminate made of aluminium and epoxy resin/glass fibre layers are shown. The classical laminate theory was used to obtain engineering constants for the macroscopic solid model and Puck criterion to obtain material data about epoxy resin/glass fibre layer. Various simulations using different simulation techniques were carried out in Simulia ABAQUS environment and results were compared with experimental data found in the literature. In conclusions, described approaches from the viewpoint of numerical simulation and experiment were evaluate. Research proves that mesoscopic (with distinguished layers of material) approach along with solid model gives the best results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

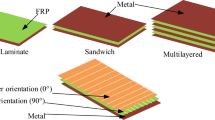

Fibre-metal laminates (labelled often as FML) are a relatively new group of materials. FMLs are structural composites that have the form of a laminate. The key characteristic of this material is the fact that this is composed of both metal and composite layers, which is the reason why they are often called hybrid composites. In present aluminium and ordinary composites materials (i.e. matrix reinforced with fibres) can be used in constructions instead of steels for cost and weight reduction purposes. However, the use of these materials also has some disadvantages such as poor fatigue strength in aluminium, low impact strength, and low residual strength. To minimize these disadvantages, it was proposed to use both materials at the same time. Researchers from Delft University of Technology showed that the rate of crack growth is lower in the material formed by bonded layers than in a homogeneous material [1].

Fibre-metal laminates as relatively new materials are not yet widely used in all branches of industry. The main obstacle is the high price and technical difficulties in processing, which is the reason why they are currently only used on a larger scale in the aviation industry. In the Airbus A-380 version, 800 large sections of the plating are made of a fibre-metal laminate called Glare [1] [2]. Other FML material called ARALL was used in Boeing C-17 Cargo and Fokker 27 constructions [1] [3].

Initially, research in aircraft industry was conducted i.e. [4]. In the last few years, an increasing number of research projects in the area of fibre-metal laminates can be observed. Papers are focused on various issues i.e. delamination process [5], low-velocity impact behaviour [6] or fatigue [7].

2 Approaches to modelling fibre-metal laminates in simulation using the finite element method

The problem of numerical analysis of laminates can be approached in various ways. Soltani et al. in their work [8] they distinguish three approaches:

-

Micromechanical—in this approach individual materials are differentiated in the model including fibres and matrix. This is the most complex approach of all described. Potentially, it is the most realistic as well, but it requires partitioning model into a lot of very small parts. This can be unfavourable so it is usually better to consider the next two approaches.

-

Mesomechanical—in this approach a laminate was considered as a system of independent layers with specific mechanical properties. Similar to the previous approach there is some simplification in skipping the issue of layers boundary. But in fact, we don’t consider it until delamination process occurs, so within the scope of the application, it is not a critical problem. The criteria of decohesion is another important issue in describing fibre-metal laminates and will be the subject of future works.

-

Macromechanical—in this approach it was described the laminate as a homogeneous body with anisotropic mechanical properties. This approach can be described as a generalization. A very simple model of material is generated—whole fibre-metal laminate is described using a few engineering constants.

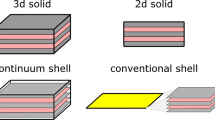

Further, the environment used in the simulation from the Simulia ABAQUS user point of view will be described. The application of the macroscopic model is the simplest solution in ABAQUS. It is possible to use built-in types of an elastic constitutive model called respectively Lamina and Engineering Constant. As described before in this approach we treat laminate as a homogeneous anisotropic material. This is possible by providing 9 engineering constants during the material creation (Young’s modulus in all three directions, three Kirchhoff modules, and three Poisson numbers), i.e. by defining material behaviour in each direction. Due to the layered structure (sometimes symmetric), laminates do not show anisotropy in all directions, so some of these constants will be equal. In ABAQUS, the type of material Lamina can also be used, which requires six constants—Young’s modulus in the plane of laminate layers, Poisson’s number and three Kirchhoff modules. The problem with this approach is obtaining the data of this imaginary homogenous material which would be a replacement for our lamina. One of the possible solutions is the use of Classical Laminate Theory which will be further described in the next chapter.

The mesomechanical model can be realised in ABAQUS in various ways. For thin objects, it is possible to use the shell model. In such a model structure of laminate is represented by Composite Layup. In this layup, there are defined all layers and their parameters such as orientation, thickness, material data, and relative location. Another possibility is to use a solid model. Using partitioning tool separated layers were extracted and all material data was defined for each of these layers separately. Regardless of the model choice, it is crucial to define local material orientation.

3 Classical laminate theory

The classic theory of laminates [9], [10] enables the description of their behaviour under the external loads based on engineering constants of particular laminate layers assuming some simplifications listed below:

-

Perfect joint with no thickness between layers,

-

No inter-layer shear effect,

-

No slip between layers,

-

Meeting the assumptions of the thin plate theory, i.e.:

-

No length and deformation change of the central plane,

-

Points contained in the normal direction to the plane also contained in this direction after deformation,

-

-

Stresses in the normal direction to the central plane are insignificantly smaller compared to in-pane stresses.

The external loads work on a single layer of the laminate:

-

In the plane of this layer determined by the directions x, y, i.e. tensile or compressive forces \(\left( {N_{x} , N_{y} } \right)\) and shearing forces \(\left( {N_{xy} } \right)\),

-

Bending (moments \(M_{x} , M_{y}\)) and twisting (\(M_{xy}\)).

For the whole material, the column vector of forces {N} and the column vector of moments {M} were defined. The load on the laminate leads to the existing deformations and curvatures. To describe them a strain tensor ε and tensor curvature κ was used. The occurrence of deformations and curvatures is tantamount to the occurrence of stresses in the material. Linking these quantities for a single layer is possible by using Eq. (1) [9] where the thickness is denoted as \(z\) and a matrix \(Q'\) is the matrix of proportional coefficients.

Using the relationships between forces along with moments and stress showed in Eq. (1), the following equations can be written for the entire laminate using some auxiliary matrixes A, B and D as [9]:

Matrixes A, B, and D have been introduced for clarification purposes and can be defined as:

-

Matrix A—stiffness tensile matrix, it is the only one having non-zero components when the material is in the membrane state of stress. The definition of its components is given in the formula (4). Summation by layers (with thickness denoted as \(z_{k}\)) makes it possible to reproduce the structure of the material;

-

Matrix B—connection stiffness matrix or Coupling Stiffness Matrix. It allows determining the mutual influence of tensioning (compression) and bending. Components of this matrix are zero when there is no bending at perfect stretching. This is possible for objects that are symmetrical in relation to their central plane both in geometry and material. The definition of its components is given by formula (5);

-

Matrix D—bending matrix. It is the only one that has non-zero components when the material is loaded with only bending and torsional moments. The definition of its components is given by the formula (6).

In formulas 4–6 [9]: \(z_{n}\) denote thickness of nth layer, \(\left( {Q'_{ij} } \right)_{k}\) means individual item in \(Q'\) matrix for kth layer, calculated from formula 1.

To simplify Eqs. (2) and (3), it can be written as one matrix equations. This way is shown in Eq. 7. The characteristic matrix which is presented in this equation is called the Matrix ABD. This matrix has rank equal to six and consist of matrixes A, D and two matrixes B.

Engineering constants (Young Modulus E, Kirchhoff Modulus G and Poisson coefficient \(\vartheta\)) of laminates in the membrane state of stress in various direction can be obtained from the following formulas [9]:

Engineering constants (Young Modulus E, Kirchhoff Modulus G and Poisson coefficient \(\vartheta\)) of laminates in the bending state of stress in various direction can be obtained from the following formulas [9]:

The assignation of engineering constants enables the presentation of a laminar material in the form of a homogeneous material with anisotropic properties defined by these constants.

4 Numerical analysis of three-point bending of fibre-metal laminates

In this article, there are presented different approaches that vary in complexity and accuracy. To present the difference between these approaches numerical simulations in Abaqus Simulia environment were conducted. In the work of Ostapiuk et al. [11] results of three-point bending experiments are presented. The subject of this research was fibre-metal laminates based on aluminium (2024 T3) and carbon fibre in epoxy resin. It was chosen the same material, so results of numerical simulations using different methods can be compared with the experimental one.

Figures 1, 2 and 3 different composition of FML, which are the subject of research are presented.

In Table 1 important mechanical properties of aluminium 2024 T3 and carbon reinforced composites are shown. Data for composite was calculated based on properties of the epoxy matrix and carbon fibre obtained from Hexcel company. Materials from this producer were used in experimental research by Ostapiuk et al. Afterwards based on this information, parameters for the composite layer are calculated using the rule of mixture (ROM) and Puck methods. Both gave very similar results. In the case of aluminium, besides elastic properties, it is equally important the characteristic plastic part. True stress—true strain data from work was used [12]. In Table 2 typical chemical composition of 2024 T3 alloy is presented.

For the homogeneous model, Classical Laminate Theory was used to obtain the data. A computer program—eLamX (version 2.3), which is developed at the Technische Universität Dresden, was used [15]. This program lets to describe laminate layer by layer using engineering constants and as the effect ABD matrixes are provided as well as a reverse matrix. Mechanical properties shown above in Table 1 were used. Table 3 contains the ABD matrix for \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|0_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) with a thickness of aluminium layer equal to 0.3 mm. In the Table 4, the reverse matrix is presented. Submatrices are highlighted by different colours – respectively blue colour for A Matrix, yellow colour for B Matrices and finally green colour for Matrix D. As expected, matrix B has all the components equal zero. Also the components A16 and A26 are equal zero. This is the result of the symmetrical structure of the laminate, so bending does not cause stretching and vice versa.

Using 8 and 9 formulas it is possible to calculate engineering constants. In these formulas, it is needed to use components from the reverse matrix (Table 4). Three-point bending is, in fact, the problem of complex loading, but one of the basic states must be chosen. In this case, loading is much more similar to the bending state of loading so Eq. 9 will be used. In the numerical simulation, the following unit system was used: \(N - mm - MPa - \frac{t}{{mm^{3} }}\), so obtained modulus of shear and elasticity are expressed in megapascals. All mechanical properties of substitutional homogenous material are shown in the Table 5. For other cases procedure is analogous.

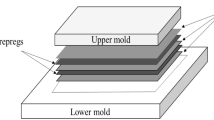

Depending on the case, specimens were modelled as a solid body or shell component. The stamp and the support roller were modelled as the rigid body so they cannot deform but they have discrete elements. Between specimen and rollers (as well as a stamp) proper contact behaviour was made so it is possible to imitate three-point bending test by the controlled move of the stamp. All degrees of freedom were taken from the rollers but the degrees of freedom for specimen were taken into consideration. In all cases, high order finite elements were used for specimens. For shell models, quadratic quadrilateral elements of type S8R were chosen. For solid models, quadratic hexahedral elements of type C3D20R were used. For a rigid body in both cases, quadrilateral elements of type R3D4 were chosen. An exemplary view of the assembly (shell model case) with finite element mesh is presented in Fig. 4. In Figs. 5 and 6 more detailed finite elements mesh is presented (solid model case).

5 Results and discussion

In this section, the results of the simulation are prepared as described in the previous section. In Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8 stress in function of centre beam deflection is presented for three different structure of fibre-metal laminates. For every type of structure various simulation were carried out taking into consideration the different approaches described in the theoretical part of this work. Stress curves obtained as a result of this simulation are compared with experimental results based on work by Ostapiuk et al. [11].

Analysing above charts it is clear that the best projection is ensured by applying mesoscopic solid model. For \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|45_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) specimen stress-displacement curve obtained from FEM analysis is nearly the same as this obtained from experiment. For other specimens, this results are in good compliance too. In Figs. 9 and 10 Huber-Mises stress map is shown for \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|45_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) and \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|0_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) specimens. Analysis of this charts gives a clue about difference in compliance for different composition of discussed fibre-metal laminate. For \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|0_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) specimen it is observed high stresses region on boundary between aluminium and CFRP layers. This may lead to delamination and in consequence decrease of stress response, as it was observed in the experiment. However, in \([{\mathbf{Al}} 2024 {\mathbf{T}}3|45_{2}^{{\varvec{CFRP}}} ]_{\varvec{s}}\) specimen high stress region is located in aluminium so simulation is a good reflection of real behaviour of specimen under three-point bending.

Numerical simulations were conducted for the medium-fine mesh. Minimum 4 elements in case of thin layer and minimum 2 elements in case of thick layer were used. In the case of shell models, 5 integration points in each layer were used. It was researched that in this case using more fined mesh gives only slightly more smooth curves and no apparent difference in results. Results were acquired every 0.05 mm displacement of the stamp.

6 Conclusions

Different methods of fibre-metal laminates modelling in the numerical environment were shown in this article. The mesoscopic approach gives better results (i.e. more convergent with experimental results) than the macroscopic approach. However, both of these methods are in good compliance with real measurement in the elastic range, so in the area of applicability of described materials. In some cases, proposed models become divergent with experimental results in case of large displacement of the stamp. It is caused by a decohesion process which occurs in the real specimen—especially delamination process. The issue of modelling destruction process will be examined by authors in future works.

References

Sinmazçelik T, Avcu E, Bora MÖ, Çoban O (2011) A review: fibre metal laminates, background, bonding types and applied test methods. Mater Des 32:3671–3685

Dincă I, Ştefan A, Stan A (2010) Aluminum/glass fibre and aluminum/carbon fibre hybrid laminates. Incas Bull 2:2066–2081

Krishnakumar S (1994) Fiber metal laminates—The synthesis of metals and composites. Mater Manuf Process 9(2):295–354

Linde P, Pleitner J, De Boer H, Carmone C (2004) Modelling and simulation of fibre metal laminates. ABAQUS users’ conference. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266268763_Modelling_and_Simulation_of_Fibre_Metal_Laminates

Sosa JL, Karapurath N (2012) Delamination modelling of GLARE using the extended finite element method. Compos Sci Technol 72:789–791

Ma YE, Hu H (2013) Experimental and numerical investigation of fibre-metal laminates during low-velocity impact loading. In: 13th international conference on fracture pp 1–4

Tomasetti T et al (2015) Finite element modeling of fatigue in fiber-metal laminates article in AIAA. Journal 29:2228–2236

Soltani P, Keikhosravy M, Oskouei RH, Soutis C (2011) Studying the tensile behaviour of GLARE laminates: a finite element modelling approach. Appl Compos Mater 18(4):271–282

Dąbrowski H (2002) Strength of polymer fiber composites.Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej (in Polish)

Nettles AT (1994) Basic mechanics of laminated composite plates. NASA Reference Publication, Alabama

Ostapiuk M, Bieniaś J, Surowska B (2018) Analysis of the bending and failure of fiber metal laminates based on glass and carbon fibers. Sci Eng Compos Mater 25(6):1095–1106

Dacko A, Toczyski J (2010) structural response of a blast loaded fuselage. J KONES Powertrain Transp 17(1):10

Prepreg Data Sheet| Hexcel. [Online]. Available: https://www.hexcel.com/Resources/DataSheets/Prepreg. [Accessed: 03-Feb-2019]

Kvackaj T (2011) Aluminium alloys, theory and applications. InTech

“eLamX2—Chair of Aircraft Engineering—TU Dresden.” [Online]. Available: https://tu-dresden.de/ing/maschinenwesen/ilr/lft/elamx2/elamx. [Accessed: 03-Feb-2019]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Smolnicki, M., Stabla, P. Finite element method analysis of fibre-metal laminates considering different approaches to material model. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 467 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0496-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0496-2