Abstract

This review summarizes the empirical literature on the effects of natural disasters and weather variations on international trade and financial flows. Regarding the effects on trade, I summarize 21 studies of 18 independent research teams and show that there is a large diversity in terms of motivations, data sets used, methodologies, and results. Still, some overarching conclusions can be drawn. Increases in average temperature seem to have a detrimental effect on export values, mainly on manufactured and agricultural products. Given climate change, this finding is important when it comes to projecting long-term developments of trade volumes. Imports seem to be less affected by temperature changes. Findings on the effects of natural disasters on trade are more ambiguous, but at least it can be concluded that exports seem to be affected negatively by the occurrence and severity of disasters in the exporting country. Imports may decrease, increase, or remain unaffected by natural disasters. Regarding heterogeneous effects, small, poor, and hot countries with low institutional quality and little political freedom seem to face the most detrimental effects on their trade flows. The literature on international financial flows is more limited. This part of the review includes 12 empirical studies. All but one focus on the effect of disasters. The majority of these studies finds that remittances and foreign aid inflows increase slightly after disasters. Potential future research could analyze spillover effects (in terms of time, space, and trade networks), consider adaptation, and use more granular data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

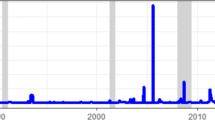

This review summarizes the empirical literature on the effects of natural disasters and weather variations on international trade and financial flows. The volume of international trade has increased in absolute terms and relative to GDP in the last decades, as illustrated by Fig. 1. In 2017, the sum of merchandise exports and imports amounted to 44% of the global production. Nowadays, many production processes are embedded in international supply chain networks and would not be feasible without an intensive cross-border exchange of goods, services and finance (Dietzenbacher et al. 2012; Hummels et al. 2001). Consequently, international trade and the exchange of financial resources are perceived as a driver of economic growth, welfare, political freedom, security, and technological innovation.

Given the high relevance of international trade and financial flows, the quantitative analysis of possible effects of natural disasters and weather variations on these two areas is an interesting research question per se. Climate change, manifested by higher temperatures, changed precipitation patterns, and more frequent and more severe extreme weather events, will further increase the relevance of this topic (IPCC 2012).

In the following, I briefly outline the relation between natural disasters, weather variations, climate and climate change. Weather variation is the temporal stochastic variation of temperature, precipitation and other weather variables (Dell et al. 2014). Natural disasters are major adverse events resulting from natural processes which may cause serious damage and the death of human beings. Except for geological or space disasters, they are usually related to extreme outcomes of weather variables. Climate can be defined as the long term distribution of weather variables (Hsiang 2016). Hence, climate change refers to a change in the stochastic long term distribution of weather. Recent IPCC reports summarize inter alia observed trends in temperature and precipitation, and project their respective future development (IPCC 2013, 2014). The key insights are that global average temperature increased by 0.85 °C between 1880 and 2012, precipitation patterns have changed and the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events have increased in many parts of the world.

Natural disasters and weather variations may affect trade via different channels: Disasters can destroy transport infrastructure such as ports, container terminals, road or railway connections, thereby raising trade costs. Disasters and weather variations can affect production (mainly in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors), and consequently the supply of tradable goods. If income is affected by weather variations or disasters, the demand for imports may change. Furthermore, imports of small developing countries may increase after a major natural disaster as a result of large inflows of external aid. International financial flows, such as foreign direct investments and equity flows, may react to changes in capital productivity induced by disasters and climate change, or – as in the case of foreign aid flows and remittances of emigrants – may be used to assist in the reconstruction process after a natural disaster. In the literature, more mechanisms than the ones already described can be found and will be described in the section on results.

In this context, there is an emerging strand of empirical economic literature which aims to identify and quantify the effects of natural disasters, weather and climatic changes on international trade and financial flows.Footnote 1 In this review, I report the main conclusions, most important data sources, and empirical methods of studies from the gray and peer-reviewed literature. To the best of my knowledge, the review takes account of all publicly available studies that meet the following criteria:

-

1.

The study is an ex-post analysis.

-

2.

The analysis focusses on international trade or financial flows as the dependent variable.

-

3.

The estimation includes dimensions of natural disasters or weather variations as an explaining variable.

-

4.

The analysis is not restricted to a single event.

Many of these studies include brief literature reviews themselves, and most find the empirical literature on the effects on trade in question to be extremely sparse. In fact, the number of the studies referenced ranges from zero to four. In contrast to these assessments, the present review shows that the number of trade studies meeting the abovementioned criteria is actually not that small but amounts to at least 21 papers published since 2008.Footnote 2 These studies can be deemed as reasonably independent from each other as just three authors contributed to more than one study. The existing literature is relatively diverse in terms of regional and temporal coverage, data sets used, disaster and weather definitions, methodologies, and main conclusions, as shown in the remainder of this review. Regarding financial flows, there are at least additional 12 studies published since 2005.

The motivations of the summarized papers are just as diverse as their data and methodology. First and foremost, the mere relevance of international trade for modern economies and societies, alongside with ongoing climate change, is the main motivation for the outlined research question. In the literature on climate change, it is well acknowledged that even if the largest and richest economies of the world were relatively resilient towards the direct (domestic) effects of global warming and natural disasters, they could be severely affected in an indirect way, namely by the impact of climate change or disaster on their trading partners. This indirect effect could even exceed direct effects (Freeman and Guzman 2009; Knittel et al. 2018; Schenker 2013; U.S. Global Change Research Program 2018). There is one particularly interesting question to be answered in the urgently-needed quantitative analysis of this potential channel of climate impacts: Are trade effects of climatic events or changes indeed already observable in ex-post analyses and how large are they?

Furthermore, there is a range of more specific motivations behind the reviewed studies: Some authors focus on developing countries because for many of these economies exports and imports are crucial for their economic development (Andrada da Silva and Cernat 2012; Cuaresma et al. 2008; El Hadri et al. 2018; Heger et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2018; Pascasio et al. 2014). There is also a focus on developing countries in most studies on financial flows, as remittances and foreign aid inflows are often key components of their national income accounts. Another motivation is the usage of trade data (which is often reported by international agencies or customs authorities) as an arguably more reliable and detailed measure of economic activity than national indicators such as GDP, which is reported by the country itself (Hsiang and Jina 2014; Jones and Olken 2010; Li et al. 2015; Mohan 2017). Moreover, some studies focus on the role of institutions and political indicators for the resilience towards natural disasters (Gassebner et al. 2010; Oh and Reuveny 2010). Cuaresma et al. (2008) and Pelli and Tschopp (2017) raise the question whether natural disasters may induce technological change via a build-back better effect and use product-specific trade data to test their hypotheses. Finally, some more isolated motivational settings include the analysis of temporal and spatial displacement of trade flows and the substitutability of ports in the USA (Sytsma 2018a), the disentangling of the total disaster effect on trade into partial effects (El Hadri et al. 2018), the disentangling of total disaster effects on GDP into its national income components (Mohan et al. 2018), and an analysis of economic impacts of hurricanes in a historical setting (Mohan and Strobl 2013).

In the following, I first focus on the effects on trade of goods and services. In this main part of the paper, I summarize the main characteristics of the 21 trade studies, present the datasets on trade, weather variations, and natural disasters, discuss the estimation methods, and synthesize the main conclusions. Second, I briefly review the adjacent literature strand on international financial flows. In the concluding section, I define some common challenges and knowledge gaps and suggest ideas for future research.

Effects on International Trade of Goods and Services

Overview of Studies

Since 2008, at least 21 studies have been published assessing ex-post the effects of climatic changes or natural disasters on international trade. Thirteen of them have been published in peer-reviewed journals, of which nine are associated to economics. Spatially, some papers focus on developing countries, geographical regions, or single countries, while nine studies include all parts of the world. In case of spatially focused studies, the selection of countries is motivated by high trade dependencies or high disaster exposure. Regarding the temporal coverage, all studies but one cover as many and recent time periods as possible. The other one analyzes historical data of the 18th and nineteenth century. While most analyses rely on annual data, a few recent publications introduce monthly estimations. Table 1 presents an overview of the studies included in this review.

Data and Methods

Trade Data

Analyzing quantitative effects on “international trade” is by no means straightforward, as trade may be operationalized in very different ways (see column 2 of Table 1). Many studies use bilateral trade flows as the dependent variable, hence they differentiate along the exporter and importer dimension. However, depending on the concrete research question, it may suffice to look at the aggregate trade flows of a country to “the world”, or to one specific country. Some scholars restrict their analysis to trade flows included in national databases, due to data quality concerns (Jones and Olken 2010). Consequently, they only consider trade flows which are either imports or exports of the given country. Some studies estimate changes in trade variables (Heger et al. 2008; Hsiang and Jina 2014; Jones and Olken 2010; Lee et al. 2018; Pascasio et al. 2014), while the majority uses level data.

Given the formulation of trade, the level of observations ranges from very granular observations (e.g. value of product k traded from exporter j to importer i in time t) to more aggregate units (e.g. total imports to country i in time t).

The data sources of bilateral trade data which are currently maintained are summarized in Table 2. It becomes apparent that most of the available data is based on data collection efforts of the United Nations Statistics Division (UN Comtrade). Some data sources reconcile these original data (e.g., by estimating and deducting freight and insurance costs, adding missing data), or complement it with data from national and regional sources. Beside those data sets, there are national trade statistics (focusing on trade flows of a specific nation), data sets without bilateral resolution, hence only displaying aggregate exports and imports of countries (e.g. IMF World Economic Outlook;Footnote 3 World Development Indicators;Footnote 4 Penn World Tables)Footnote 5, and some datasets which are seemingly not updated any more (e.g. NBER Trade Data;Footnote 6 World Trade Analyzer).

Weather and Disaster Data

Broadly spoken, the presented studies can be divided into two strands of literature, which are relatively independent from each other: The first one covering slow onset weather effects, the second one focusing on natural disaster effects on trade. Column 5 of Table 1 depicts the focus of the studies, showing that a majority of 16 publications analyze trade effects of natural disasters.

Concerning the concrete formulation of weather variables, all authors use the (population-weighted) average annual temperature and precipitation of the trading countries or cities. Dallmann (2019) also studies effects of temperature and precipitation differences between the trade partners, arguing that relative differences between the weather shocks may affect productivity differences, and hence trade flows. The exclusive usage of annual weather data (instead of temporally more disaggregated data) implies that possible intra-annual variations are not yet exploited in this branch of the literature. In contrast, El Hadri et al. (2018) show for the case of natural disasters, that disasters are only harmful for agricultural exports if they hit the exporter during the growing season of its main crop. Concerning temperature and precipitation effects on trade, there no study yet using season-specific weather data. Weather data are available at the grid cell level, in different temporal resolutions and downloadable from various climate data repositories (for a short summary of the most used datasets see Table 3). In general, the operationalization of weather is relatively uniform in this strand of literature.Footnote 7

On the other side, the 16 studies on natural disasters come up with more than 16 approaches for measuring disasters or their severity, depending on their concrete research question and data availability. These approaches can be grouped into three categories, depending on how much importance the authors place on the exogenous character of the disaster variable. The first group of studies uses purely physical measures of disasters such as hurricane wind speeds or earthquake magnitudes (El Hadri et al. 2018; Hsiang and Jina 2014; Mohan 2017; Mohan et al. 2018; Pelli and Tschopp 2017; Sytsma 2018a). The sources for such disaster data include the ifo GAME dataset (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014), and several sources for locations and wind speed of tropical storms (see Table 3). The second group is a relatively large body of literature which bases its research on the widely-used international disaster database of the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (EM-DAT) (EM-DAT (n.d.), Guha-Sapir et al. (n.d.)). EM-DAT includes information on occurrence and impacts of natural and man-made disasters since 1900. Despite its unquestioned strengths in terms of temporal and regional coverage, the data set implies some methodological challenges, in particular for economic analyses. An event is classified as a disaster and enters the database if its socioeconomic impacts surpass certain thresholds. This was criticized because the probability that an event is acknowledged as a disaster depends on a country’s socioeconomic variables (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014). Hence there is a selection bias, and the events are not completely exogenous. Some authors try to mitigate this problem by focusing on severe disasters (Andrada da Silva and Cernat 2012; Gassebner et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2018), disaster measures which are apparently orthogonal to economic activities (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2013), and the mere occurrences and number of disasters instead of severity measures (El Hadri et al. 2018; Mohan and Strobl 2013; Oh 2017; Oh and Reuveny 2010; Tembata and Takeuchi 2019). Several authors argue that the physical size of the country should be taken into account and estimate the effects of disasters per km2 (Cuaresma et al. 2008; Gassebner et al. 2010). Finally, Heger et al. (2008) is the only study in the third category, using economic impacts (damage) of natural disasters in the main analysis. Since the economic damage of disasters and their effects on trade may be affected by the same characteristics of a country – e.g. degree of resilience – this approach should be subject to endogeneity concerns.

Control Variables and Heterogeneous Effects

Depending on the empirical strategy, different covariates may be included in the estimation. First let us consider data on the country-year level. Most gravity regressions include the GDP or the GDP per capita of the trading countries. Focusing on agricultural trade, Barua and Valenzuela (2018), El Hadri et al. (2018), and Mohan (2017) extend the usual gravity equation with measures of productivity in the agricultural sector. A number of studies includes indicators of institutional quality or political freedom (Gassebner et al. 2010; Oh and Reuveny 2010). Time-invariant characteristics such as latitude or geographical size are normally controlled for by country-fixed effects. The second set of covariates captures variables at the country-pair-level. These include free trade agreements and other trade policy indicators, the geographical or economic distance between trade partners, the product of both countries’ GDPs, adjacency, common historical relationships, common culture and language, and multilateral remotenessFootnote 8 indicators. However, instead of including numerous time-invariant characteristics of country-pairs, many studies estimate fixed effects for country-pairs.

Many authors are interested in heterogeneities in the effects of weather or natural disasters on trade flows and include interaction terms or divide the sample into subsamples. Thirteen studies mention heterogeneous results as part of their baseline results, sometimes as the central result. Typical sources of heterogeneity are geographical and economic preconditions of the affected country or city, and the quality of institutions.

Estimation Methodologies

The regression models employed in the reviewed studies are as diverse as the formulation of dependent variables and levels of observation. Mostly, the underlying estimation method is a fixed effects panel estimator. However, the source of fixed effects differs dramatically (time, country, country-pair, industry, industry-by-time, country-by-time, country-by-industry, country- or industry-specific time trends …). The same applies to the estimation of standard errors, which are clustered at various units. Another aspect is the treatment of zero-trade flows, which becomes particularly relevant for very granular observations at the product level, and for large panel data of bilateral trade flows. Depending on the level of observation, the majority of trade flows in the data may actually be zero. However, if trade flows are log-transformed, zero-trade flows are omitted. Indeed, most studies seem to omit this considerable data portion, and do not use the full information available in the data (Helpman et al. 2008). The only two exceptions which explicitly tackle this issue employ versions of the Pseudo Poisson Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimator proposed by Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006) to account for zero-trade flows (Dallmann 2019; Felbermayr and Gröschl 2013). Mohan et al. (2018) is the only reviewed study which uses a panel Vector Autoregressive with an exogenous shock (VARX) framework which captures feedback effects between the national income components.

Regarding the estimation of heterogeneity across economic sectors or product categories, there are three broad categories describing how sector-specific results are obtained. First, authors restrict the total analysis on the sector of interest (Barua and Valenzuela 2018; Cuaresma et al. 2008; El Hadri et al. 2018; Mohan and Strobl 2013). Second, they repeat the baseline estimation for different subsamples (Barua and Valenzuela 2018; Dallmann 2019; Jones and Olken 2010; Oh 2017Footnote 9; Mohan 2017; Pascasio et al. 2014; Tembata and Takeuchi 2019). Third, they employ estimations at a level of observation which includes sector or product categories (e.g., at the sector-countrypair-year-level) (El Hadri et al. 2018; Jones and Olken 2010; Li et al. 2015; Pascasio et al. 2014; Pelli and Tschopp 2017).

The diversity regarding dependent variables, covariates, and estimation methods suggests that there is currently no methodology which is widely-accepted as the state-of-the-art for estimating gravity style regressions related to natural disaster or weather effects. There are also no clear differences between peer-reviewed papers and the gray literature in this regard. For bilateral trade flows, however, the PPML approach is definitely a step forward, at least if zero-trade flows are important.

Results

General Effects (no Interaction Effects)

Given the diversity of the concrete formulation of trade flows, disaster variables and estimation methodologies, a summary of the main findings of the reviewed studies is not straightforward. Table 4 summarizes the baseline results. Note that only results for the full samples, without any subsample analyses or interaction effects, are included.

By tendency, the literature finds negative effects of high temperatures on exports. Apparently, temperature shocks are detrimental to economic activity, and ultimately decreases the supply of tradable goods (this channel is explicitly suggested by Dallmann 2019 and Pascasio et al. 2014). A very robust result is that agricultural exports are particularly affected. In the agricultural sector, production declines sharply under extremely high temperatures (Moore and Lobell 2015; Schlenker and Roberts 2009) and if adverse temperature levels occur in specific phases of the growth cycle (Auffhammer et al. 2012). Beside these phenology-related processes, temperature affects production in the agricultural and other sectors by reducing labor productivity. Heat is related to lower work intensity (Seppänen et al. 2006), cognitive performance (Graff Zivin et al. 2018), and labor supply (Graff Zivin and Neidell 2014). In sum, these effects contribute to an overall lower economic production implied by high temperature (Burke et al. 2015; Dell et al. 2012). Importantly, macro-level analyses show that the evidence for adaptation – in form of a reduced sensitivity towards higher temperatures in more developed countries – is relatively limited (Carleton and Hsiang 2016). This implies that negative effects on exports, induced by heat-related production losses, may further increase with an ongoing climate change. Imports, however, seem to be less responsive to temperature shocks.

Regarding precipitation, there are ambiguous results ranging from negative effects on both kinds of trade flows to positive effects on exports. While equally distributed precipitation may be beneficial for some agricultural products (Barrios et al. 2010), too intensive rainfall may also affect production processes negatively (Fishman 2016). Hence, the distribution of precipitation within a growing season is crucial for how agricultural production is ultimately affected. Note that available studies with a focus on precipitation, by using annually averaged data, cannot depict this inter-annual variation. This may explain the inconclusive results regarding precipitation effects on trade.

Turning to the effects of natural disasters, the body of literature yields partly contradicting results as well. What can be concluded is that exports do not seem to benefit from natural disaster occurrence.Footnote 10 The decline of exports is mostly reasoned by the production losses caused by the disaster (Gassebner et al. 2010; Mohan 2017; Mohan et al. 2018; Mohan and Strobl 2013; Oh and Reuveny 2010). Production losses may occur if disasters destroy productive capital or durable consumption goods (such as housing) which are replaced using funds which are then no longer available for productive investments (Hsiang and Jina 2014; IPCC 2012). Some authors also mention destroyed transport infrastructure as a possible impact channel (El Hadri et al. 2018; Gassebner et al. 2010; Oh and Reuveny 2010; Oh 2017). However, Sytsma (2018a) finds no effect on imports to U.S. ports, which questions the relevance of the infrastructure channel in this specific setting.

Imports may decrease, be unaffected, or increase after a natural disaster struck the importer. Decreases are reasoned by income effects: If available income declines after a natural disaster, the demand for imported goods follows (Hsiang and Jina 2014; Oh and Reuveny 2010; Oh 2017). Obviously, interruptions of transport networks may be relevant for the decline of imports as well. For increases of imports, different channels are hypothesized: First, there may be consumption smoothing – countries increase their imports to replace domestic production (described by Oh and Reuveny 2010, found by Felbermayr and Gröschl 2013). Second, damaged countries may need to import reconstruction goods and capital (Gassebner et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2018; Mohan et al. 2018), which is partly in the form of external disaster relief – this notion is supported by some of the interaction effects and the findings of financial flows studies.

Sector-specific results are only reported in a minority of the natural disaster studies. El Hadri et al. (2018), Mohan (2017), and Mohan and Strobl (2013) focus on exports of agricultural goods, and find mixed results. Tembata and Takeuchi (2019) report relatively larger effects of floods and storms on agricultural exports than on manufactured exports. In contrast, Oh (2017) finds significant positive effects on agricultural trade, while most other industries are negatively affected. Also Pelli and Tschopp (2017) differentiate between economic sectors, focusing on their comparative advantage. These results are presented in the next sub-section.

Interaction Effects

The wide variance of qualitative results, not to speak of quantitative estimates, calls for a deeper investigation of the heterogeneities behind these results. This is often done via the estimation of interaction effects and subsamples. From the review, some quite robust relationships emerge:

Trade (imports and exports) is affected more negatively if a disaster hits a country with low-quality institutions or low levels of political freedom (Dallmann 2019; Gassebner et al. 2010; Oh and Reuveny 2010). The reason given for this is resilience or a lack of it. Well-functioning institutions may be conducive to an economy which is relatively resilient towards natural disasters and climatic changes. Relatedly, effects on imports and exports are more negative in relatively poor economies (Barua and Valenzuela 2018; Cuaresma et al. 2008; Jones and Olken 2010; Li et al. 2015; not confirmed by Pascasio et al. 2014). This may partly be explained by temperature effects on economic production, which may also be more negative in poor countries (Dell et al. 2012), although later studies did not confirm that heterogeneity in the production–temperature relationship (Carleton and Hsiang 2016). In the case that poor countries exhibit more positive disaster effects on their imports, this is often interpreted as inflow of external disaster relief (Lee et al. 2018, Oh and Reuveny 2010, see also section on financial flows). Furthermore, geographically small countries and exporters which have a relatively hot climate face more negative effects on trade flows (Andrada da Silva and Cernat 2012; Dallmann 2019; Gassebner et al. 2010; Li et al. 2015). Some studies suggest that negative effects of high temperature are more pronounced for trade pairs with high initial trade costs (Dallmann 2019; Li et al. 2015), but for natural disasters this interaction effect is not confirmed (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2013).

Beside these relatively robust interaction effects, some studies introduce more unique interaction effects, motivated by their particular research questions. Pelli and Tschopp (2017) show that hurricanes decrease exports only for industries with low comparative advantage, while they may even increase exports of very competitive industries. The authors conclude that hurricanes, by destroying capital of partly non-competitive industries, induce firms to invest in new technologies during the reconstruction process. In a sense, hurricanes unexpectedly reduce the costs of technological transformation. El Hadri et al. (2018) show that natural disasters only affect agricultural exports negatively if they hit rural areas and occur during the respective growing seasons. Moreover, they suggest that exports to culturally close trade partners do not decline but even increase after natural disasters hitting the exporter – a finding which is interpreted as “solidarity-consistent effect”.

Effects on International Financial Flows

So far, the review has focused on the effects of disasters and weather on international trade of goods and services. Trading, however, constitutes only one part of international economic relations. In this section, I therefore briefly summarize the empirical literature on the effects of natural disasters and weather variations on international financial flows, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign aid, remittances of emigrants, bank lending, and equity flows. Table 5 provides an overview on the 12 studies included in this part of the review.

Looking at the type of financial flows, the spatial coverage, and the disaster or weather variables, one can gain at least two immediate insights: First, the literature focusses on those financial flows which are most relevant in a development context (such as remittances and foreign aid flows). Consequently, the countries studied are predominantly low- or middle income countries, and half of the studies have been published in journals dedicated to development economics. Second, there is only one study which looks at the effect of average weather variations (Arezki and Brückner 2012), while the remainder researches the effects of natural disasters. In terms of datasets, there is much less variation than in the trade literature – ten out of eleven disaster studies are based on the EM-DAT dataset (the only exception being Yang 2008, which is based on HURDAT, see Table 3).

The majority of the studies finds that the inflows of remittances increase after the occurrence of disasters (Amuedo-Dorantes et al. 2010; Bluedorn 2005; David 2011; Mohapatra et al. 2012), although the effect is sometimes very small, delayed or non-significant (Lueth and Ruiz-Arranz 2008; Naudé and Bezuidenhout 2014). Other studies control for heterogeneity in the response of remittances, and find the positive effect to prevail mainly for poor countries (Yang 2008) and for countries with less developed financial systems (Arezki and Brückner 2012; Bettin and Zazzaro 2018). These results are compatible with the notion that emigrated workers support their relatives more in the wake of a disaster. This suggests that remittances have an insurance character, which is most relevant in countries with less developed formal financial markets. In a similar vein, one may expect foreign aid to increase after disasters. Indeed, positive effects are identified (Amuedo-Dorantes et al. 2010; Bluedorn 2005; Yang 2008), albeit Becerra et al. (2014) emphasize that they are relatively minor and Raddatz (2007) does not find any effect. Again, effects seem stronger in poorer countries and after more intense disasters (Becerra et al. 2014; David 2011). Regarding FDI and other private capital flows, the very sparse literature provides a mixed picture. While FDI inflows seem to react negatively to natural disasters in a global analysis (Filer and Stanišić 2016), they are found to be insignificantly affected in developing countries (Yang 2008).

Conclusions and Research Gaps

This review of the empirical literature on the effects of natural disasters and weather variations on international economic relations demonstrates that the body of literature has grown rapidly in recent years. Focusing on the trade of goods and services, I summarize 21 studies of 18 independent research teams and show that there is a large diversity in terms of motivations, data sets used, methodologies, and results. The empirical literature on international financial flows encompasses at least 12 studies published since 2005.

Some overarching conclusions can be drawn which are at least not contradictory to most of the studies. First, increases in average temperature seem to have a detrimental effect on export values, mainly in case of manufactured and agricultural products. Given climate change, this is an important finding for projecting long-term developments of trade volumes. Findings on the effects of natural disasters are more ambiguous, but exports seem to be affected negatively by occurrence and severity of disasters in the exporting country. Imports may decrease, increase, or be unaffected by natural disasters. Regarding heterogeneous effects, apparently small, poor, and hot countries with low degrees of institutional quality and political freedom face the most detrimental effects on their trade flows. Remittances and foreign aid flows may slightly increase in the wake of natural disasters, while the findings on other financial flows are more ambiguous.

While underlying channels and mechanisms are outlined by most studies (most comprehensively by Oh and Reuveny 2010), formal economic theories on the effects on trade flows are discussed relatively rarely. Notable exemptions are Felbermayr and Gröschl (2013), who refer to a theory on consumption smoothing after a disaster shock, and El Hadri et al. (2018), who formally separate the total disaster effect into a transport infrastructure effect, a production effect and a solidarity-consistent effect. Moreover, the studies related to creative destruction (Cuaresma et al. 2008; Pelli and Tschopp 2017) refer to the endogenous growth theory and theories of comparative advantage. In contrast to the literature on trade, most studies on financial flows present deliberate theoretical frameworks, such as the neo-classical growth model, investment theories, risk sharing and consumption smoothing models.

This review offers some directions for further research. Few studies (Dallmann 2019; Jones and Olken 2010) deliberately raise the issue of price effects. While weather variations or natural disasters may affect the production and supply of sensitive products, their prices may increase after the negative supply shock. As most studies measure trade in monetary terms (the only exceptions being Mohan (2017) and Mohan & Strobl (2013) who use quantities of agricultural goods), the price effect may mask possible supply effects. Dallmann (2019) controls for this by integrating national inflation rates as a robustness check. This takes account of national macroeconomic price changes, but does not capture global price shocks of certain products. The latter are included as product-year-fixed effects by Jones and Olken (2010). Future research could – as a first step – follow these approaches to control for possible price effects, or – going beyond existing approaches – develop estimation models which explicitly estimate and include price shocks.

Another topic which has been addressed by some studies is the temporal persistence of the measured effects. By and large, if lagged effects are estimated, they prove to be significant for considerably long time spans (up to 20 years after a temperature shock as in Dallmann (2019)). Given the variety of results regarding the temporal persistence, more theoretical and empirical studies on the dynamic behavior of trade or financial flows after external shocks may be needed.

On a different note, beside the temporal dimension there may also be spatial spillovers of natural disasters or weather shocks. So far, the shocks were modeled as if they affected only the countries in which they occurred. Future works could try to include possible spillover effects on adjacent countries. Beside this geographical dimension, spillover effects may also occur via supply chains. If country A, due to a natural disaster, cannot export crucial raw materials to country B, the trade of processed goods from country B to country C may be affected as well. Such spillover effects on international trade flows have not yet been analyzed empirically, although there is an emerging strand of literature on similar spillover effects on consumption, output and welfare via trade channels (Barrot and Sauvagnat 2016; Costinot et al. 2016; Sytsma 2018b).

Furthermore, the issue of adaptation deserves higher attention. Dallmann (2019) has suggested to use cross-sectional data to analyze long-term effects of weather variations, implicitly including adaptation behavior. Notwithstanding the methodological challenges of this approach, her finding is that there may be adaptation regarding precipitation shocks (e.g., irrigation technologies), but seemingly no effective adaptation to temperature shocks. Hsiang and Jina (2014) find that the effect of cyclones on imports is larger in countries with less historical cyclone experience, and interpret this finding as an evidence of adaptation. Beside these two – quite generic – formulations of adaptation, this issue is rarely raised in the literature.

Finally, some recent studies demonstrate strategies to use more granular data to refine empirical estimates: The use of trade data with higher temporal, spatial, and sectoral resolution. Monthly trade data become increasingly available (e.g., at UN Comtrade), and are used in an increasing number of studies. However, a global analysis of monthly trade is still missing. Furthermore, available monthly weather data could be used in trade analyses, which would allow analyzing the effects of temperature and precipitation during growing seasons of specific agricultural goods (as done by El Hadri et al. 2018 for natural disasters). Regarding the spatial dimension, Sytsma (2018a, b) introduces estimates at the port level. Thereby he tackles the problem that countries with the highest economic relevance (USA, China) are also geographically large, implying that the exact locations of external shocks are particularly important, but not depicted in many data sets. In terms of sectoral heterogeneity, studies with a high sectoral resolution have shown quite remarkable differences between economic sectors and agricultural products (Dallmann 2019; Jones and Olken 2010; Mohan 2017; Oh 2017). As data on trade and financial flows at sector-, product- or firm-level becomes increasingly available, future research should not neglect these dimensions. Consequently, one possible next step in this literature may be to estimate trade and financial flows at the firm level, accounting for firm heterogeneities and eventually exact locations of the production sites.

Notes

There are related bodies of empirical literature which analyze disaster or climate effects on economic growth (e.g. Cavallo et al. 2013; Noy 2009), migration (Boustan et al. 2012; Marchiori et al. 2012), or conflicts (Slettebak 2012). An excellent overview of climate effects on health, agriculture, income, and conflict is provided by Carleton and Hsiang (2016). In this review, I focus on the effects on international trade and financial flows.

This may partly be explained by the fact that not every author is citing gray literature. Furthermore, most authors working on natural disasters cite mainly literature on those effects, and put less focus on works on weather variations (and vice versa). Given different mechanisms behind the studied effects, this is not necessarily an oversight but often reasonable.

http://www.nber.org/data/, described in Feenstra et al. 2002 and Feenstra et al. 2005

The concept of multilateral remoteness takes into account that not only the simple trade costs between trade partners matters, but also the relative trade costs compared to other potential partners.

The study of Oh (2017) is unique in using the BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis) industry classification. Other studies use SITC or HS product classifications.

If positive effects are obtained, they refer to export per GDP ratios. However, GDP may be negatively affected by natural disasters, resulting in a positive effect on the export per GDP ratio (Heger et al. 2008).

References

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Pozo S, Vargas-Silva C (2010) Remittances in Small Island developing states. J Dev Stud 46(5):941–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220381003623863

Andrada da Silva, J., & Cernat, L. (2012). Coping with loss: the impact of natural disasters on developing countries’ trade flows (EU Commission Chief Economist Note No. Issue 1–2012). Brussels, Belgium

Arezki R, Brückner M (2012) Rainfall, financial development, and remittances: evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. J Int Econ 87(2):377–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.12.010

Auffhammer M, Ramanathan V, Vincent JR (2012) Climate change, the monsoon, and rice yield in India. Clim Chang 111:411–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0208-4

Auffhammer M, Hsiang SM, Schlenker W, Sobel A (2013) Using weather data and climate model output in economic analyses of climate change. Rev Environ Econ Policy 7(2):181–198

Barrios S, Bertinelli L, Strobl E (2010) Trends in rainfall and economic growth in Africa: a neglected cause of the African growth tragedy. Rev Econ Stat 92(2):350–366 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27867541. Accessed 6 June 2019

Barrot, J.-N., & Sauvagnat, J. (2016). Input specificity and the propagation of idiosyncratic shocks in production networks. Q J Econ, 131(3), 1543–1592. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw018.Advance

Barua, S., & Valenzuela, E. (2018). Climate change impacts on global agricultural trade patterns: evidence from the past 50 years. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Sustainable Development 2018. United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network and Columbia University, USA

Becerra O, Cavallo E, Noy I (2014) Foreign aid in the aftermath of large natural disasters. Rev Dev Econ 18(3):445–460

Bettin G, Zazzaro A (2018) The impact of natural disasters on remittances to low- and middle-income countries. J Dev Stud 54(3):481–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1303672

Bluedorn, J. C. (2005). Hurricanes: Intertemporal Trade and Capital Shocks (Department of Economics Discussion Paper no. 241, University of Oxford). Oxford, UK

Boustan LP, Kahn ME, Rhode PW (2012) Moving to higher ground: migration response to natural disasters in the early twentieth century. Am Econ Rev 102(3):238–244

Burke M, Hsiang SM, Miguel E (2015) Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527:235–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15725

Carleton, T. A., & Hsiang, S. M. (2016). Social and economic impacts of climate. Science, 353(6304), aad9837. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9837

Cavallo E, Galiani S, Noy I, Pantano J (2013) Catastrophic natural disasters and economic growth. Rev Econ Stat 95(5):1549–1561

Costinot A, Donaldson D, Smith C (2016) Evolving comparative advantage and the impact of climate change in agricultural markets: evidence from 1.7 million fields around the world. J Polit Econ 124(1):205–248. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20079

Cuaresma JC, Hlouskova J, Obersteiner M (2008) Natural disasters as creative destruction? Evidence from developing countries. Econ Inq 46(2):214–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2007.00063.x

Dallmann I (2019) Weather variations and international trade. Environ Resour Econ 72(1):155–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0268-2

David AC (2011) How do International financial flows to developing countries respond to natural disasters? Glob Econ J 11(4):1–36. https://doi.org/10.2202/1524-5861.1799

Dell M, Jones BF, Olken BA (2012) Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am Econ J Macroecon 4(3):66–95

Dell M, Jones BF, Olken BA (2014) What do we learn from the weather? The new climate-economy literature. J Econ Lit 52(3):740–798

Dietzenbacher E, Pei J, Yang C (2012) Trade, production fragmentation, and China’s carbon dioxide emissions. J Environ Econ Manag 64(1):88–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEEM.2011.12.003

El Hadri H, Mirza D, Rabaud I (2018) Why natural disasters do not Lead to exports disasters in developing countries. In: University of Orléans. Orléans, France

EM-DAT. (n.d.). The emergency events database. Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) – CRED, Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from www.emdat.be. Accessed 6 June 2019

Feenstra, R. C., Romalis, J., & Schott, P. (2002). U.S. Imports, Exports, and Tariff Data, 1989-2001 (NBER Working Paper No. 9387, National Bureau of Economic Research). Cambridge, MA, USA. https://doi.org/10.3386/w9387

Feenstra, R. C., Lipsey, R. E., Deng, H., Ma, A. C., & Mo, H. (2005). World Trade Flows: 1962–2000 (NBER working paper no. 11040, National Bureau of Economic Research). Cambridge, MA, USA

Felbermayr G, Gröschl J (2013) Natural disasters and the effect of trade on income: a new panel IV approach. Eur Econ Rev 58:18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.11.008

Felbermayr G, Gröschl J (2014) Naturally negative: the growth effects of natural disasters. J Dev Econ 111:92–106

Filer RK, Stanišić D (2016) The effect of terrorist incidents on capital flows. Rev Dev Econ 20(2):502–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12246

Fishman R (2016) More uneven distributions overturn benefits of higher precipitation for crop yields. Environ Res Lett 11(024004)

Freeman J, Guzman A (2009) Climate change and U.S. interests. Columbia Law Review, vol 109, pp 1531–1602

Gassebner M, Keck A, Teh R (2010) Shaken, not stirred: the impact of disasters on international trade. Rev Int Econ 18(2):351–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2010.00868.x

Graff Zivin J, Neidell M (2014) Temperature and the allocation of time: implications for climate change. J Labor Econ 32(1):1–26

Graff Zivin J, Hsiang SM, Neidell MJ (2018) Temperature and human Capital in the Short and Long run. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 5(1):77–105

Guha-Sapir, D., Below, R., & Hoyois, P. (n.d.). EM-DAT: International Disaster Database. Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from www.emdat.be. Accessed 6 June 2019

Heger, M., Julca, A., & Paddison, O. (2008). Analysing the Impact of Natural Hazards in Small Economies The Caribbean Case (research paper no. 2008/25, UNU world Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER)). Helsinki, Finland

Helpman E, Melitz M, Rubinstein Y (2008) Estimating trade flows: trading partners and trading volumes. Q J Econ 123(2):441–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjr050

Hsiang SM (2016) Climate Econometrics. Ann Rev Resour Econ 8:43–75

Hsiang, S. M., & Jina, A. S. (2014). The Causal Effect of Environmental Catastrophe on Long-Run Economic Growth: Evidence from 6,700 Cyclones (NBER working papers no. 20352, National Bureau of Economic Research). Cambridge, MA, USA

Hummels D, Ishii J, Yi K-M (2001) The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade. J Int Econ 54:75–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00093-3

IPCC. (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. (C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, Q. Dahe, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, C. B. Field, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S. K. Allen, M. Tignor, P. M. Midgley, Eds.). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srex/SREX_Full_Report.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019

IPCC. (2013). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. (T. F. stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. M. B. Tignor, K. Allen, Simon, J. Boschung, … P. M. Midgley, Eds.). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/. Accessed 6 June 2019

IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. (C. B. field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, … L. L. White, Eds.). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/. Accessed 5 June 2019

Jones BF, Olken B a (2010) Climate shocks and exports. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 100(2):454–459. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.454

Knittel, N., Jury, M. W., Bednar-Friedl, B., Bachner, G., & Steiner, A. (2018). The implications of climate change on Germanys foreign trade: A global analysis of heat-related labour productivity losses (Graz economics papers no. GEP 2018–20). Graz, Austria

Lee, D., Zhang, H., & Nguyen, C. (2018). The economic impact of natural disasters in Pacific Island countries: adaptation and preparedness (IMF Working Paper No. WP/2018/108). Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/05/10/The-Economic-Impact-of-Natural-Disasters-in-Pacific-Island-Countries-Adaptation-and-45826. Accessed 6 June 2019

Li C, Xiang X, Gu H (2015) Climate shocks and international trade: evidence from China. Econ Lett 135:55–57

Lueth E, Ruiz-Arranz M (2008) Determinants of bilateral remittance flows. B.E. J Macroecon 8(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1690.1568

Marchiori L, Maystadt J-F, Schumacher I (2012) The impact of weather anomalies on migration in sub-Saharan Africa. J Environ Econ Manag 63:355–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.02.001

Mohan P (2017) Impact of hurricanes on agriculture: evidence from the Caribbean. Natural Hazards Review 18(3):1–13

Mohan P, Strobl E (2013) The economic impact of hurricanes in history: evidence from sugar exports in the Caribbean from 1700-1960. Weather, Climate, and Society 5:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-12-00029.1

Mohan PS, Ouattara B, Strobl E (2018) Decomposing the macroeconomic effects of natural disasters: a National Income Accounting Perspective. Ecol Econ 146:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.09.011

Mohapatra S, Joseph G, Ratha D (2012) Remittances and natural disasters: ex-post response and contribution to ex-ante preparedness. Environ Dev Sustain 14(3):365–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-011-9330-8

Moore FC, Lobell DB (2015) The fingerprint of climate trends on European crop yields. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(9):2670–2675. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409606112

Naudé, W. A., & Bezuidenhout, H. (2014). Migrant remittances provide resilience against disasters in Africa. Atl Econ J, 42(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-014-9403

Noy I (2009) The macroeconomic consequences of disasters. J Dev Econ 88(2):221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.02.005

Oh CH (2017) How do natural and man-made disasters affect international trade? A country-level and industry-level analysis. J Risk Res 20(2):195–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2015.1042496

Oh CH, Reuveny R (2010) Climatic natural disasters, political risk, and international trade. Glob Environ Chang 20(2):243–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.005

Pascasio, M. C., Takahashi, S., & Kotani, K. (2014). Effects of climate shocks to Philippine international trade (Economics & Management Series No. EMS-2014–07, International University of Japan, IUJ Research Institute)

Pelli M, Tschopp J (2017) Comparative advantage, capital destruction, and hurricanes. J Int Econ 108:315–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.07.004

Raddatz C (2007) Are external shocks responsible for the instability of output in low-income countries. J Dev Econ 84(1):155–187 Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304387806001842. Accessed 6 June 2019

Santos Silva JMC, Tenreyro S (2006) The log of gravity. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):641–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.641

Schenker O (2013) Exchanging goods and damages: the role of trade on the distribution of climate change costs. Environ Resour Econ 54(2):261–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-012-9593-z

Schlenker W, Roberts M (2009) Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to U.S. crop yields under climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(37):15594–15598

Seppänen, O., Fisk, W. J., & Lei, Q. H. (2006). Room temperature and productivity in office work. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Retrieved from http://www.hut.fi. Accessed 6 June 2019

Slettebak RT (2012) Don’t blame the weather! Climate-related natural disasters and civil conflict. J Peace Res 49(1):163–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311425693

Sytsma, T. (2018a). Boon or Bane? Temporal and Spatial Dynamics in the Response of Port-Level Trade to Hurricanes. (University of Oregon, Department of Economics) retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3067531. Accessed 6 June 2019

Sytsma, T. (2018b). Do Domestic Trade Frictions have Global Consequences ? The Welfare Impact of Hurricanes Activity around US Ports. (University of Oregon, Department of Economics)

Tembata K, Takeuchi K (2019) Floods and exports: an empirical study on natural disaster shocks in Southeast Asia. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 3(1):39–60

U.S. Global Change Research Program. (2018). Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II: Report-in-Brief. (D. R. Reidmiller, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, K. L. M. Lewis, T. K. Maycock, & B. C. Stewart, Eds.). Washington, D.C., USA: U.S. Government Publishing Office. Retrieved from https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/16/. Accessed 6 June 2019

Yang D (2008) Coping with disaster: the impact of hurricanes on international financial flows, 1970-2002. BE J Economic Analysis Policy 8(1)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Suborna Barua, Ingrid Dallmann, Christian Kind, Chang Hoon Oh, Oliver Schenker, Tobias Sytsma, Kaori Tembata, and two anonymous referees for their constructive and precious comments. The underlying research project is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany under the funding ID 01LA1817B. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Osberghaus, D. The Effects of Natural Disasters and Weather Variations on International Trade and Financial Flows: a Review of the Empirical Literature. EconDisCliCha 3, 305–325 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-019-00042-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-019-00042-2