Abstract

Background

Patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) have high healthcare resource use (HRU) due to respiratory and nutritional complications resulting from progressive muscle atrophy. While previous studies estimate the direct costs to be US$113,000 to US$121,682 per year in the US, they potentially understate costs for type 1 SMA (SMA1). This study analyzed HRU in hospitalizations with a diagnosis of SMA1 and compared it with hospitalizations with complex chronic conditions (CCC) other than SMA1 or those with no CCC.

Methods

This retrospective analysis of a defined subset of the 2012 Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) compared a nationally estimated number of hospitalizations of children (aged < 3 years) categorized into three groups: (1) SMA1 (n = 237 admissions), (2) no CCC (n = 632,467 admissions), and (3) other CCC (n = 224,953 admissions).

Results

Mean total charges were higher for SMA1 admissions compared with admissions with no CCC (US$150,921 vs US$19,261 per admission, respectively; costs: US$50,190 vs $5862 per admission, respectively; both p < 0.0001). A larger proportion of SMA1 admissions were billed for one or more procedure codes (81.9%) than in the no CCC group (39.4%) or other CCC group (70.1%; both p ≤ 0.0003). SMA1 admissions had a longer length of stay compared with admissions with no CCC (15.1 vs 3.4, respectively; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

The average total charges for a single SMA1 admission were higher than those of the no CCC group. Because most infants with SMA1 require multiple hospitalizations per year, previous estimates may dramatically underestimate the direct costs associated with HRU. Further studies are required to determine the indirect costs and societal impacts of SMA1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mean total charges for spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1) admissions were higher than those with no complex chronic conditions (CCC) (US$150,921 vs US$19,261, respectively); the total costs were also higher in SMA1 admissions |

SMA1 hospitalizations were 4.4-fold longer compared with those of children with no CCC (15.1 vs 3.4 days, respectively); a larger proportion of SMA1 admissions were billed for one or more procedures (81.9% vs 39.4%, respectively) |

The average total charges for a single SMA1 admission exceeds the yearly estimates of all care costs previously reported for SMA patients. Because children with SMA1 experience an average of 4.2 hospitalizations annually, the annual charges for the care of SMA1 patients may be far higher than previous studies suggest |

1 Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disease that is characterized by alpha motor neuron degeneration in the spinal cord and subsequent muscular atrophy and weakness, resulting from the loss or dysfunction of survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1). The incidence of SMA is approximately 1 in 10,000 live births, with a carrier frequency of 1 in 54 [1]. SMA is classified into four subtypes (1–4), of which 60% of patients are diagnosed with the most severe form, SMA type 1 (SMA1) [2]. Most SMA1 patients have two copies of SMN2 and experience disease onset before 6 months of age, marked by progressive hypotonia, severe weakness, and nutritional and ventilatory failure. By definition, these children never gain the ability to sit [3].

SMA1 management requires close monitoring and proactive supportive care as a result of progressive pulmonary failure and swallowing dysfunction, leading to chronic aspiration and failure to thrive [4]. In recent years, the clinical management of SMA1 patients has evolved with advances in multidisciplinary supportive care such that the basic care needs of the patient are emphasized [5]; advances include early, proactive pulmonary care (e.g., airway clearance and noninvasive ventilatory support [5]), scoliosis surgical strategies [6], and nutritional support optimization [4]. As a result, a greater proportion of SMA1 children are receiving supportive care [3, 7]. The proportion of patients receiving ventilatory support increased from 31% in patients born in 1980–1994 to 82% in those born in 1995–2006; the proportion receiving gastrostomy tube feeding increased from 40 to 78%, respectively [7]. Early respiratory and nutritional management has altered the natural history of SMA1 patients by increasing their survival [7, 8]. However, the increased survival has not been accompanied by concomitant improvements in motor function or milestone achievement [9], or health-related quality of life [10].

Even with increased supportive care, SMA1 children continue to have high healthcare resource utilization (HRU) as they commonly develop pulmonary infections and aspiration pneumonia that require intensive pulmonary support superimposed upon chronic ventilatory needs. Care required to manage respiratory illnesses in SMA1 patients often includes invasive ventilatory support and extended hospitalization in an intensive care unit setting. SMA1 children experience an average of approximately 4.2 hospitalizations annually [11] with a mean length of stay that ranges from 10 days [12] to 13 days [13]. The frequent and prolonged hospitalizations result in escalating direct medical costs attributed to inpatient care in addition to outpatient care, ancillary services, and specialized equipment [13, 14]. The national economic burden of early onset SMA in the US in 2010 was estimated to be US$684 million, including US$427 million in medical costs [15]. The total annual direct costs for early-onset SMA children range from US$112,644 to US$121,682 per patient [15, 16]. These cost estimates are likely an underestimation as a more recent analysis by Shieh et al. [11] estimated that the monthly costs of inpatient hospitalization in patients with infantile SMA were US$21,863, increasing to US$52,234 in the first month after adjusting for mortality.

Previous studies of the burden of SMA1 are limited in their small sample size (n = 8 and n = 20 SMA1 patients, respectively) [10, 17]. Also, previous studies did not differentiate between SMA types and were subject to miscoding and misdiagnosis [11, 15, 16]. Thus, the present retrospective study was undertaken to determine the HRU in hospitalizations of SMA1 patients and compare it with hospitalizations of patients with complex chronic conditions (CCC) other than SMA1 as well as hospitalizations of patients with no CCC. We hypothesized that the cost of illness for patients hospitalized with an SMA1 diagnosis is likely much higher than currently estimated.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This retrospective analysis of a defined subset of the most recent complete dataset (2012) from the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) compared the HRU of patients in the following three groups: (1) those with SMA1, (2) those without a CCC (no CCC), and (3) those with types of CCC other than SMA1 (other CCC). Hospitalizations were included if patients were < 3 years of age at enrollment. This age cut-off decision was based upon survival data from previous natural history studies [3, 18]. The KID is divided into three categories: (1) complicated in-hospital births, (2) normal uncomplicated in-hospital births, and (3) all other pediatric cases. The first two categories were excluded from the present analysis.

2.2 Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) Analysis

The KID provides clinical and nonclinical data elements for each hospital stay, including patient demographics (e.g., age in years and sex), expected insurance type, procedure codes billed, length of hospital stay, and total charges for all inpatient services for individual inpatient hospitalizations from hospitals in 44 states in the US [19]. Cost-to-charge ratio files are also included to estimate the resource costs of inpatient care. As part of the Healthcare Cost & Utilization Project (HCUP) Database derived from hospital billing information, it is an all-payer database that includes Medicaid, private insurance, and uninsured claims.

CCC hospitalizations were filtered by ICD-9 codes to identify patients who are at risk for death [20]. CCC categories are neuromuscular (e.g., brain and spinal cord malformations, mental retardation, central nervous system degeneration and disease, infantile cerebral palsy, epilepsy, muscular dystrophies, and myopathies), cardiovascular (e.g., heart and great vessel malformations, cardiomyopathies, conduction disorders, and dysrhythmias), respiratory (e.g., respiratory malformations, chronic respiratory disease, and cystic fibrosis), renal, gastrointestinal, hematology and immunodeficiency, metabolic, other congenital or genetic defect (e.g., chromosomal abnormalities, bone and joint abnormalities, diaphragm, and abdominal wall), and malignancy.

Hospitalizations were categorized as SMA1 if they included an ICD-9CM Diagnosis code of 335.0 ‘Werdnig-Hoffmann disease’ using International Classification of Diseases—9th Revision—Clinical Modification (2009 ICD-9CM). These hospitalizations are considered neuromuscular CCCs. All CCCs other than SMA1 were categorized as ‘other CCC’. Hospitalizations without any CCCs were classified as ‘no CCC’.

Healthcare costs and resource utilization variables for this analysis include hospital admissions, length of stay, and total charges per admission. The complexity of care was also evaluated by assessing the number of procedure codes billed per admission. SMA1 diagnosis and procedure codes are shown in Table 1. The primary outcome measures were hospital charges (total and daily), direct medical costs, number of procedures billed, and length of stay.

2.3 Charges and Costs

In the US healthcare system, hospital charges and costs differ [21]. Total charges are fixed and represent the amount the hospital billed for admission services during the entire hospital stay and exclude professional fees. Hospital costs reflect how much hospital services actually cost to providers. For payers, costs represent the amount paid to providers for services. Costs are based on negotiated rates and differ by payer. Total charges were converted to costs using HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios (CCRs) for each hospital from the KID. CCRs were based on hospital accounting reports from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [20].

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The weighted means and proportions (with 95% confidence intervals) were computed from continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Overall comparisons were performed using t-tests or Chi square tests, as appropriate. Survey procedures were used to account for the unique sampling design of the KID, which included a weighting factor to provide nationwide estimates. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Hospitalizations and Patient Characteristics

This retrospective analysis includes a nationwide estimate of 237 admissions in the SMA1 group, 632,467 hospital admissions in the no CCC group, and 224,953 admissions in the other CCC group. The largest proportion of admissions in this analysis occurred when patients were < 1 year of age in all groups, including 62.7% of the SMA1 group, 63.5% of the no CCC group, and 59.8% of the other CCC group (Table 2). Hospitalizations were classified as female in 56.9% of the SMA1 group, 44.1% of the no CCC group, and 43.6% of the other CCC group (Table 2). Whereas most children were insured by Medicaid in the no CCC and other CCC groups (60.4 and 57.1%, respectively), SMA1 children were primarily insured by either Medicaid or private insurance (45.3 and 45.9%, respectively; Table 2).

3.2 Individual Inpatient Charges and Costs per Hospitalization

The mean total charges billed per admission for SMA1 children is higher when compared with hospitalizations with no CCC (mean US$150,921 vs US$19,261 per admission, respectively; p < 0.0001; Fig. 1a and Table 2). Although the mean total charges for SMA1 hospitalizations were also higher than those of the other CCC group, it was not statistically significant (mean US$150,921 vs US$112,453, respectively; p = 0.0654). The average daily hospital charges for each SMA1 hospitalization were also higher than hospitalizations with no CCC (US$11,143 vs US$5990, respectively; p < 0.0001; Fig. 1b), whereas the average daily charges for each SMA1 hospitalization were marginally higher than those of other CCC hospitalizations (US$10,359; p = 0.3497). The average total cost of each SMA1 hospitalization was also higher than that of no CCC hospitalizations (mean US$50,190 vs US$5862 per admission, respectively; p < 0.0001; Fig. 1c and Table 2).

Total (a) and daily (b) hospital charges and (c) total costs per admission for patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1), no complex chronic conditions (CCC), or other CCC. Box indicates interquartile range, diamond indicates mean values, line within the box indicates median values. Outliers are omitted from the figure

3.3 Length of Hospital Stay

Individual SMA1 hospitalizations were 4.4-fold longer than hospitalizations with no CCC (mean 15.1 days vs 3.4 days, respectively; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2 and Table 2). This mean length of SMA1 hospital stay was also longer than that of hospitalizations categorized as other CCC (11.8 days); however, it was not statistically significant (p = 0.1116). The proportion of individual SMA1 hospitalizations resulting in death (13.4%) was 112-fold greater than amongst children with no CCC (0.12%; Table 2).

Length of hospital stay per admission for patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1), no complex chronic conditions (CCC), or other CCC. Box indicates interquartile range (Q3–Q1); diamond indicates mean values; line within the box indicates median values. Outliers are omitted from the figure

3.4 Procedure Codes per Admission

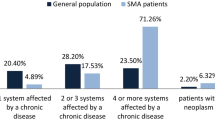

The KID lists up to 50 procedure codes per record with most hospitalizations having one or more procedure codes billed. A larger proportion of SMA1 hospitalizations were billed for one or more procedure codes compared with no CCC or other CCC hospitalizations (81.9% vs 39.4% and 70.1%, respectively; both p ≤ 0.0003; Fig. 3a and Table 2). The proportion of hospitalizations in each group with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥ 5 procedure codes billed per admission is shown in Fig. 3b.

Number of procedure codes billed per admission (a) and proportion of patients in each group with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥ 5 procedure codes billed per admission (b). Box indicates interquartile range (Q3–Q1); diamond indicates mean values; line within the box indicates median values. Outliers are omitted from the figure

As shown in Fig. 4a, 38.3% of SMA1 hospitalizations had procedure codes billed for nutritional support compared with 2.9% in the no CCC group and 19.3% in the other CCC group. In addition, 66.1% of SMA1 admissions had procedure codes billed for ventilatory support compared with 3.3% in the no CCC group and 20.3% in the other CCC group. Figure 4b and c show a more detailed analysis of the top ten SMA1 procedure codes, including continuous positive airway pressure, continuous mechanical ventilatory support ≥ 96 h, enteral infusion nutritional support, continuous mechanical ventilatory support < 96 h, insertion of an endotracheal tube, other gastrostomy, other venous catheter, creation of an esophageal sphincter, parenteral infusion of nutrition substances, and closed bronchial biopsy. With the exception of other venous catheter and parenteral infusion of nutrition substances, which were similar in both the SMA1 and other CCC admissions (Fig. 4c), all of the other top SMA1 procedures were billed in a higher proportion of SMA1 admissions.

The proportion of admissions including procedure codes for nutritional and ventilatory support (a) and proportion of admissions involving each of the top ten billed procedures for type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1), presented for each group (SMA1, no complex chronic conditions [CCC], and other CCC) (b, c)

4 Discussion

Data from the KID demonstrated that SMA1 hospitalizations were lengthy and extremely costly, particularly when compared with hospitalizations with no CCC. The average total hospital charges per SMA1 hospitalization were US$150,921 (US$11,143 per day) compared with those of the no CCC group, which were US$19,261 (US$5990 per day). Moreover, the average total hospital costs per SMA1 hospitalization were higher than those in the no CCC group (US$50,190 vs US$5862, respectively). SMA1 hospitalizations were longer than those of the no CCC group (15.1 vs 3.4 days, respectively). SMA1 hospitalizations billed for more procedures than hospitalizations with no CCC (81.9% vs 39.4% billing for one or more procedure codes, respectively); many of these procedures were for nutritional and ventilatory support. Thus, the high hospitalization charges observed for SMA1 hospitalizations appear to be due to both the longer duration and increased complexity of the care provided.

Although more recent studies analyzing the burden of SMA in the US have reported high annual direct costs [11, 15, 16], they fail to analyze costs associated with specific SMA types. Specifically, the total healthcare expenditures associated with patients with an SMA diagnosis at ≤ 3 years of age ranged from US$112,644 [16] to US$121,682 [15]. After adjusting for mortality, the total costs for infantile SMA patients were 14-fold higher than matched non-SMA patients in the first month (US$52,234 vs US$3731, respectively). By month 30, this gap widened to 56-fold (US$574,197 vs US$9828) [11]. In line with clinical experience and studies suggesting the high annual cost of care for SMA1 children [11, 15,16,17], we found that the average total hospital charges for a single hospitalization for SMA1 patients were US$150,921 with total costs of US$50,190. Given that SMA1 children experience an average of approximately 4.2 hospitalizations annually [11], and care requirements for SMA1 children also include outpatient care, ancillary services, specialized equipment, and prescription costs, the results suggest that the annualized HRU for SMA1 patients is potentially far beyond that previously reported in small data sets likely biased towards older, long-lived patients with relatively mild disease.

In addition to high direct annual costs, SMA is also associated with additional costs, which are often described as ‘hidden costs’, including costs associated with appointments (e.g., transportation costs), time (e.g., time off work and time spent accessing care), financial costs associated with condition management (e.g., private insurance, respite care, and specialist equipment), and psychosocial/health and wellbeing (e.g., disruption of schooling, impact on relationships, and depression). In a nationwide cross-sectional study in Germany that included 189 patients with SMA1-3, the total annual direct medical cost of illness among 12 patients surveyed with SMA1 was €53,707, increasing to €107,807 after the addition of direct non-medical costs as well as indirect costs [17]. Another small population-based cross-sectional study in Spain that included 81 SMA patients reported that the total annual costs for SMA patients were €10,882 in direct healthcare costs and €22,839 in direct non-healthcare costs [10]. Although both the German and Spanish studies were small with relatively few SMA1 patients (n = 12 [6%] in Klug et al. [17] and n = 8 [10%] in Lopez-Bastida et al. [10]) and most of the participants were older and more chronic in their disease, both studies highlight the considerable burden of SMA beyond direct medical costs, including both direct non-healthcare costs and indirect costs.

The high resource use described in the current study is not surprising as it is consistent with standard of care guidelines, which stress the proactive multidisciplinary care necessary to manage SMA1 symptoms [4]. In a retrospective study of 49 SMA1 patients, proactive management of respiratory symptoms, including cough assist, noninvasive ventilatory support, and invasive ventilation (i.e., tracheostomy), was associated with increased survival time compared with supportive care [22]. This proactive care approach also increased the rate of hospitalization for respiratory insufficiency and shortened the time from diagnosis to hospitalization for respiratory insufficiency [22]. Proactive supportive care was also associated with increased care costs compared with supportive care (median costs of US$116,988 vs US$76,746 over a 686-day period, respectively) [22].

In the present study, the total charges were converted to total costs using CCRs provided by the KID. Analysis of the total costs revealed that they were approximately one-third the total charges for each group. This is consistent with previously published HRU studies using the KID, which reported charges that were 2.7- [23] and 3.2-fold [24] higher than the costs.

The present study is limited in that it only focused on the costs associated with individual hospitalizations and does not directly assess per-patient charges as well as the acuity of care. In addition, it was not a longitudinal analysis, and no adjustments were made to control for confounding across the three groups. Furthermore, charge-to-cost conversion ratios were hospital-specific; therefore, the true conversion rate may vary substantially across treatments. In an analysis of the economic burden of SMA, the primary costs were associated with outpatient visits; total prescription costs were also high [16]. Therefore, a large portion of the costs associated with SMA were not captured in the KID dataset. Furthermore, respiratory morbidity is affected by the level of supportive care utilized by the patient. Although standard of care, at the time, specifies ventilatory and nutritional support, use is variable in the general population as some parents elect that their child receive maximal supportive care whereas other select palliative-only care without treatment. Because supportive care use in these cases cannot be determined using the KID dataset, these estimates likely represent a mixture of high-use children and low-use children. Finally, these estimates were made from the KID 2012 dataset, which is before the approval of nusinersen, the first disease-modifying drug approved for SMA; thus, these estimates would not necessarily be generalizable to patients treated with this drug.

5 Conclusions

The average hospitalization charges for a single SMA1 admission exceed the yearly estimates of all care costs previously reported for SMA patients. The per-day hospitalization charges for SMA1 children are nearly double those required for children with no CCC. In addition, the duration of hospitalizations is far longer for SMA1 with an increased number of procedure codes billed, contributing to the high charges observed for hospital care of these admissions. Because children with SMA1 experience an average of 4.2 hospitalizations annually [11], this data suggests that the annual charges for the care of SMA1 patients, none of whom were treated with nusinersen, may be far higher than the current peer-reviewed literature suggests. Further studies are required to determine the complete burden of SMA1 in the US, including indirect costs and societal impacts, and the impact of newly available and emerging therapies on overall care costs.

Data Availability Statement

The Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) is one in a family of databases and software tools developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The KID has been released approximately every 3 years since 1997 and includes data elements from hospital discharge abstracts for children in participating states. The KID includes data on diagnoses, procedures, admission and discharge status, demographics, charges and insurance status, length of stay, and hospital characteristics (such as teaching status and size). Data can be accessed after completion of a Data Use Agreement, online training, and an application kit as well as a fee sent to the HCUP Central Distributor at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/centdist.jsp.

References

Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of > 72,400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:27–32.

Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy—a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:124.

Finkel RS, McDermott MP, Kaufmann P, et al. Observational study of spinal muscular atrophy type I and implications for clinical trials. Neurology. 2014;83:810–7.

Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, et al. Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1027–49.

Sproule DM, Kaufmann P. Therapeutic developments in spinal muscular atrophy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:173–85.

Haaker G, Fujak A. Proximal spinal muscular atrophy: current orthopedic perspective. Appl Clin Genet. 2013;6:113–20.

Oskoui M, Levy G, Garland CJ, et al. The changing natural history of spinal muscular atrophy type 1. Neurology. 2007;69:1931–6.

Ioos C, Leclair-Richard D, Mrad S, et al. Respiratory capacity course in patients with infantile spinal muscular atrophy. Chest. 2004;126:831–7.

De Sanctis R, Coratti G, Pasternak A, et al. Developmental milestones in type I spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord: NMD. 2016;26:754–9.

Lopez-Bastida J, Pena-Longobardo LM, Aranda-Reneo I, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Spain. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:141.

Shieh PB, Gu T, Chen E, et al. Treatment patterns and cost of care among patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Orlando: Cure SMA; 2017.

Teynor M, Hou Q, Zhou J, et al. Healthcare Resource Use in Patients with Diagnosis of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in Optum™ U.S. Claims Database (P4.158). Neurology. 2017. pp. 88.

Teynor M, Zhou J, Hou Q, et al. Retrospective analysis of healthcare resource utilization (HRU) in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in MarketScan® (P3.186). Neurology. 2017. pp. 88.

Callan MB, Haskins ME, Wang P, et al. Successful phenotype improvement following gene therapy for severe hemophilia a in privately owned dogs. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151800.

Mendell JR. Reply to letter to the editor. Mol Ther. 2017;25:2238–40.

Armstrong EP, Malone DC, Yeh WS, et al. The economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Econ. 2016;19:822–6.

Klug C, Schreiber-Katz O, Thiele S, et al. Disease burden of spinal muscular atrophy in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:58.

Kolb SJ. Longitudinal results from the NeuroNeXT SMA infant biomarker study. Anaheim: CureSMA Annual Meeting; 2016.

HCUP Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID). Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP). 2012. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. 2012.

Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106:205–9.

Arora V, Moriates C, Shah N. The challenge of understanding health care costs and charges. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:1046–52.

Lemoine TJ, Swoboda KJ, Bratton SL, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy type 1: are proactive respiratory interventions associated with longer survival? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e161–5.

Spencer JD, Schwaderer A, McHugh K, et al. Pediatric urinary tract infections: an analysis of hospitalizations, charges, and costs in the USA. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:2469–75.

Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, et al. Childhood asthma hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1127–33):e3.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the HCUP Data Partners that contribute to HCUP (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/hcupdatapartners.jsp).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have commented on the submitted manuscript and have given their approval for the final version to be published. JM, MM, MH, and DS analyzed the data. JM and MH drafted the manuscript. DS acts as overall guarantor for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by AveXis, Inc.

Conflict of interest

Jessica Cardenas, Melissa Menier, and Douglas M. Sproule are current or former employees of AveXis, Inc. Marjet D. Heitzer is a contract medical writer for AveXis, Inc.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cardenas, J., Menier, M., Heitzer, M.D. et al. High Healthcare Resource Use in Hospitalized Patients with a Diagnosis of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1 (SMA1): Retrospective Analysis of the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID). PharmacoEconomics Open 3, 205–213 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-018-0093-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-018-0093-0