Abstract

Rainfall is an important triggering factor influencing the stability of soil slope. Study on some influences of the rainfall on the instability characteristics of unsaturated soil embankment slope has been conducted in this paper. First, based on the effective stress theory of unsaturated soil for single variable, fluid–solid coupling constitutive equations were established. Then, a segment of red clay embankment slope, along a railway from Dazhou to Chengdu, damaged by rainfall, was theoretically, numerically, and experimentally researched by considering both the runoff-underground seepage and the fluid–solid coupling. The failure characteristics of the embankment slope and the numerical simulation results were in excellent agreement. In the end, a sensitivity analysis of the key factors influencing the slope stability subjected to rainfall was performed with emphasis on damage depth as well as infiltration rainfall depth. From the analysis in this paper, it was concluded that the intensity of rainfall, rainfall duration, and long-term strength of soil have most effects on slope stability when subjected to rainfall. These results suggest that the numerical simulation can be used for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Rainfall in mountains and hills regions, such as in Southwest China, is often heavy and prolonged; thus, disasters associated with slope instability induced by rainfall usually happen, resulting in severe impacts to the transportation systems, human beings’ safety, and wellbeing [1,2,3]. Therefore, it has become a significant and urgent subject to take rainfall into account as a considerable factor in slope stabilizing [4, 5].

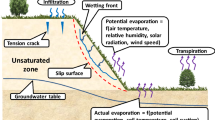

Slope instability induced by rainfall is affected by both water flows on slope surface and water infiltration. Generally, water flow on slope surface produced by rainfall mainly includes two basic types [6, 7], of which one so-called “super-infiltration surface runoff” occurs when the rainfall intensity exceeds the infiltration capacity of the slope, and the other occurs after the rainfall along the instauration shallow regions and finally transfers into surface flow when the regions are saturated. In geotechnical engineering, problem caused by ‘super-infiltration surface runoff’ is not uncommon, so more attention has been paid on it. The process of water infiltration into the slope induced by the rainfall consists of two stages [8]: the first is the “complete-infiltration stage,” which happens when the rainfall intensity and the duration are low. The rain water is able to completely infiltrate into the soil matrix and there is little residual water to form surface runoff. The second is pressured-infiltration stage which forms after the soil has become saturated. These two stages are not strictly separated or sequent because the infiltration and runoff are determined by many factors, such as the soil percolation characteristics, rainfall intensity, rainy duration, and groundwater table. Most of the current analysis methods for rainfall infiltration usually simplify the surface runoff, in which the assumption is taken that the surface runoff completely drains away instantly, and the depth of surface standing water is zero. By this way, the boundary conditions and rainfall influences on slope infiltration are taken into consideration [6, 9,10,11,12]. As a consequence, these analyzing methods cannot completely reflect the actual processes and mechanisms of rainfall infiltration and soil yielding when subjected to runoff [6, 13]. Accurately estimating the runoff in surface areas and also considering the effects of depth of standing water on the infiltration could be helpful to accurately estimate the quantity of the infiltration, as well as the variation of the pore water pressure. Hence a more precise yield analysis of slope stability and slope reinforcement can be presented. At present, the numerical analysis methods of slope stability under rainfall condition have the limit equilibrium method [6, 9,10,11, 14], finite element method [15,16,17], numerical simulation of fluid solid coupling of unsaturated soil [18, 19]. The stabilization enhancement of soil slope can be achieved by various means such as consolidation and compaction, soil replacement, physical and chemical improvement, earth reinforcement, relief well and other anti-water infiltration and retaining engineering facilities [20,21,22,23,24].

With the rapid development of high-speed rail and highways in mountain regions of China, attentions focused on slope instability induced by rainfall, especially for natural soil slope and road cuts, have become higher and higher. This type of slope failure is usually characterized by shallow failure whose destroying depth is usually less than 3 m above the groundwater table, and generally with small volume on steep soil slopes of 30°–50° [25, 26]. In addition to China, in many other regions, such disasters induced by rainfall are also common and confusion, such as Hongkong [25], Taiwan [27], and Korean [28]. Similar researches for the triggering mechanism and treatments of the rainfall inducing slope failure have been performed. Some of these achievements have been combined into the local engineering practices [29,30,31]. In regions of rainfall-induced slope failure, pore water pressure and infiltration force may form in the region of slope surface, and may cause shallow surface failure, then gradually induce complete failure of the entire slope. This problem has gradually gained wide recognition.

Relative engineering projects and researches [6, 9, 11, 32] have been conducted by simplifying boundaries of rainfall infiltration. The temporary distribution of matrix suction has been calculated using the unsaturated seepage of underground water, and the stability assessment method of limited-equilibrium theory based on the shear-strength theory of unsaturated double stress invariants \((\sigma - {u_{\text{a}}})\) and \(({u_{\text{a}}} - {u_{\text{w}}}).\) However, the solid–fluid coupling effect during infiltration is sparsely been considered. In addition, the failure of slope is gradual due to the fact that the stress deviates from the average of the soil. Thus, failure first occurs in regions of high shear stress, and then causes the nearby regions to fail as a result of shear stress transfer to the un-softened soil. This process continues until a new equilibrium forms, ending in local failure or complete failure. For road embankments subjected to rainfall, failure of the slope surface often occurs and then causes cracks or subsidence to the entire body, but in short time, total and complete, instability rarely happens. Even so, cracks or subsidence are also not allowed, especially for high-speed railways.

In this paper, the fluid–solid coupling equations of two-phase unsaturated air–water have been established based on the effective stress theory of single variable unsaturated soil. By using the well-known FLAC software [33] and its own FISH program and C++program connector, the solid–fluid coupling program of ground surface flow and underground infiltration has been implemented. At the same time, the road foundation stability under rainfall has been analyzed using the coupling method.

2 Constitutive Model of Runoff-Underground Seepage Coupling

2.1 Flow Model of Surficial Water

For simplification, the rainfall intensity is assumed to be a constant value. In order to consider the influence of slope and rainfall direction to the slope surface, in practice, the Chezy formula or Manning Equation can be taken to substitute the momentum equation, and with unit-width flow, that is \(g=uh\) on the slope surface. Subsequently, the governing formulas of Saint Venant Slope Current can be revised as (1) [34]

where n is the coefficient of roughness as defined by Engman [35]; x is coordinate value of x-axis; g is the acceleration of gravity; and \(u\), \(h\), and q stand for the velocity of flow and location of x on the slope, the water depth as well as the rate of flow, respectively; \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(I\), respectively, express the slope angle, the rainfall direction (which is determined by the intersection angle to the vertical direction, with the counterclockwise direction as the positive direction), and rainfall strength, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1.

2.2 Flow Model of Underground Water

By the continuity equations of the underground water movement, the basic differential equations of two-phase water-air flow in embankment can be deducted from the principle of the mass conservation law, which is detailed as (2)

where \({S_{\text{a}}}\) and \({S_{\text{w}}}\), respectively, are saturations of air and water, and they satisfy the relationship that \({S_{\text{a}}}+{S_{\text{w}}}=1\); \({H^{\text{a}}}\) and \({H^{\text{w}}}\) are the air head and the water head, respectively; \({q_{\text{a}}}\) and \({q_{\text{w}}}\) refer to the sources of air and water, respectively; and \({\rho _{\text{a}}}\) and\({\rho _{\text{w}}}\) refer to density of air and water, respectively; x i is the Cartesian coordinates, i = x, y, and z.

2.3 Implementation of Surface Runoff and Underground Water Infiltration Coupling

In conjunction with the governing equations of surface water and underground water (1)–(3), the coupling is realized by way of infiltration between surface and underground water. The alternating iterative method was taken to analyze the coupling of surface and underground water. The flow chart of the coupling process is provided in Fig. 2.

3 The Fluid–Solid Coupling Model of Unsaturated Soil

The particles of the soil are assumed to be incompressible, and the characteristics of fluid–solid interaction can be stated as follows: (1) the effective stress increment is Terzaghi effective stress, and the pore pressure is replaced by fluid pressure increment of average saturated weight; (2) the volumetric strain is produced by effective stress according to Terzaghi Theory; (3) the volumetric strain affects the changing of fluid pressure; (4) Bishop effective stress [36, 37] is applied to check the plastic yielding of the constitutive model.

Based on Biot consolidation theory, unsaturated soil fluid–solid coupling model must satisfy the fluid equilibrium equation, momentum equilibrium equation, compatibility equation, as well as other requirements such as conduction, capillarity, fluid and mechanical constitutive equation laws, respectively.

3.1 Conduction Law

The governing equations of water and air migrations can be expressed as (3) by Darcy’s Law:

where \({k_{ij}}\) is saturated flow coefficient, which is a tensor defined as the ratio of intrinsic permeability to dynamic viscosity; \({\kappa _{\text{r}}}\) is relative permeability of the fluid, an empirical function of saturation \({S_{\text{w}}}\); \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity; P is the pore pressure; \(\rho\) is the fluid density; g is the acceleration of gravity.

3.2 Capillary Law

Capillary pressure is the difference of pore pressure in the fluid, expressed as \({P_{\text{c}}}=({P_{\text{g}}} - {P_{\text{w}}})\), which is an empirical function of effective saturation.

3.3 Flow Equilibrium Law

For the slightly compressible fluid, the equilibrium relation is as follows:

where \(\xi\) is the change of fluid volume (that is the change of the volume of unit-volume fluid in the porous material); \({q_v}\) is the volume strength of fluid source.

3.4 Fluid Constitutive Law

where \({K_{\text{w}}}\) and \({K_{\text{g}}}\) are bulk modulus of fluid and air, respectively; \(\varepsilon\) is the volumetric strain.

By combining Eqs. (4) and (5), one gives

3.5 Momentum Equilibrium Equations

where \(\rho\) is the volume density, and \(\rho ={\rho _{\text{d}}}+n({s_{\text{w}}}{\rho _{\text{w}}}+{s_{\text{a}}}{\rho _{\text{a}}}),\) in which \({\rho _{\text{a}}}\) and \({\rho _{\text{w}}}\) are air and fluid densities, respectively; \({\rho _{\text{d}}}\) is the dry density of the soil; and \(\dot u\) is the velocity.

3.6 Mechanical Constitutive Law

The incremental constitutive model of the pore matrix is expressed as

where \(\Delta {\sigma '_{ij}}\) is the change of the effective stresses, whose expression is \(\Delta {\sigma '_{ij}}=\Delta {\sigma _{ij}}+\bar \Delta \bar P{\delta _{ij}}\), in which \(\bar \Delta \bar P={S_{\text{w}}}\Delta {P_{\text{w}}}+{S_{\text{a}}}\Delta {P_{\text{a}}}\) [36, 37]; H is the functional form of the constitutive law. The Coulomb–Mohr Strength Model was adopted in this paper; \(\kappa\) is the parameter of stress-paths.

3.7 Geometric Compatibility Equation

According to the assumption of small-strain and the assumption that the compressive strain is set as positive, the geometric equations of soil are expressed as

4 The Influence of Fluid–Solid Coupling on the Stability of a Slope

4.1 Basic Conditions of the Slope

To ensure whether the influence of fluid–solid coupling on the embankment should be considered, the finite element meshed model shown in Fig. 3 is established. Due to symmetry of the embankment, only the left part of the embankment is illustrated, in which, the height of the slope is 10 m, the slope ratio is 1:1.5, and the width of the slope crest is 10 m too. Only the infiltration produced by the vertical rainfall on the slope surface has been considered, and the flow of air is also allowed. In this model, the fillers of the embankment consist of red clay soil (whose particles were crushed to below 2 mm), the compaction coefficient is 0.9 (defined as the ratio of dry density to the maximum dry density). The soil parameters are listed in Table 1, where the parameters of unsaturated soil were inversely deduced based on RBF neural network model [38], the coefficient of roughness is 0.035, and the initial saturation \({S_{\text{w}}}\) is 0.5. The rainfall intensity is 100 mm h−1; the duration of rainfall is 3 h, so the rainfall total sums up to 300 mm. The analyses are carried out respectively with and without consideration of the fluid–solid coupling.

4.2 “Factor of Safety (FOS)” Distribution

Figures 4 and 5, respectively, show the zones where the FOS is less than 1.0, which are actually the potential failure ones in the slope. In Fig. 4, the fluid–solid coupling (in which the unsaturated infiltration calculation is ahead of the mechanical calculation) is not considered, whereas, in Fig. 5, the fluid–coupling effect was considered.

The FOS is defined as follows:

where \({c_{\text{s}}}\) and \({\phi _{\text{s}}}\) are cohesion strength and internal friction angle, respectively, under the corresponding water saturation of “1”; \({\sigma '_1}\) and \({\sigma '_3}\) are the maximum and the minimum principal effective stresses based on the Bishop effective stress principle [37].

Comparing Fig. 4 with Fig. 5, it can be indicated that the slope did not fail when fluid–solid coupling was without considered. Under the condition that the fluid–solid coupling was considered, shear failure zones have extended 0.15 m in depth from the slope toe to 0.33 m from the slope top, forming a concave band whose ends bulge outwards. The bulging zones have formed a range between 0.15 and 1.43 m from the toe, and another range between 0.33 and 1.04 m from the top. The shear failure zones substantially parallel the slope surface. This indicates that the seepage pressure produced by infiltration fluid and the pore pressure changes caused by the volume change is obvious influencing the failure depth and range, so the fluid–solid coupling cannot be neglected.

Figure 6 shows the variation of the FOS at section “1-1.” For plane Section “1-1,” (shown in Fig. 3), due to the shallow failure performance, only a horizontal depth of 1.5 m away the slope surface is considered in this study. From Fig. 6 at the section “1-1,” one can find that the FOS of the slope is all larger than performing in no failure occur when fluid–solid coupling is not considered, whereas, a shear failure zone with a width of 0.21 m developed when the fluid–solid coupling influence has been included.

Distribution of FOS versus the horizontal failure depth away from the slope surface in Section “1-1” (in Fig. 3)

5 A Project Illustration Using the Coupling Model

Along the Dazhou-Chengdu Railway Line (connection two main cities in east and central Sichuan Province, southwestern China) between K240 + 10 and K240 + 70, due to a prolonged rainfall lasting from Aug. 7th–8th 2005, plastic failure occurred on the slope, resulting in the road shoulder’s sinking and cracking. The field investigation revealed that at the bottom of the roadbed there was a lateral slope of about 5°. The length of the right side was 21.5 m and that of the left side was 15.3 m. The slope gradient was 1:1.75; strip rocks were used as the slope protection. Seven arches were formed with it. Each arch was about 6.4 m wide. Five of the arches were squeezed and bulged. The relatively worse soil plastic deformation was notable in two of those arches (Fig. 7). Through field sampling analysis, the soil in the slope body was determined to be red clay fill. The compaction coefficient had a value of 93%, and the moisture content was 11.5%. Based on the local meteorological data, the rainfall intensity was 5 mm h−1 and lasted about 50 h.

The impact of the stone arch slope protection is not considered. Assuming the slope is bare, and adopting the simplified calculating model as shown in Fig. 7, it is found that the zones of plastic failure calculated by numerical calculation conform to the bulging zones observed in the slope. This verifies the feasibility and validity of the coupling analytic and calculating theory determined previously above for the analysis of slope stability during rainfall.

5.1 Investigation of the Effect of Each Factor

In order to demonstrate how each factor impacts the stability of the slope, calculations have been conducted by varying individual factors, such as slope gradient, slope height, percolation properties, rain intensity, compaction coefficient, and long-term strength. Two key indexes “ L/L0” (ratio of failure length to the total length of the slope surface) and failure depth (depth perpendicular to slope surface) are selected to reveal the influences. The soil parameters of the red clay fill are listed in Table 1. The value range of each factor is determined according to relative engineering practices and the authors’ experiences. The values listed have basically concluded the situations of the realistic engineering in similar projects. In the end, the factors which mainly influence the results have been selected on a comparative basis.

5.1.1 The Effect of Slope Gradient

The slope gradient was classified into six cases as 1:1.25, 1:1.35, 1:1.45, 1:1.55, 1:1.65, and 1:1.75. The other conditions are the same as described in Sect. 4.1. The results are shown in Fig. 8, which indicates how the ratio \(L/{L_0}\) varies along with the slope gradient changes after a 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. From Fig. 8, it is found that \(L/{L_0}\) stays in the narrow range of 0.952–0.963. When the slope gradient is 1:1.35 (36.5°), \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its maximum value of 0.963. When the slope gradients are 1:1.55 and 1:1.65 (32.83°) 1:1.55(31.23°), \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its minimum 0.952.

In Fig. 8, it is also shown how the failure depth of the slope at section “1-1” varies with slope gradient variation after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfalls. With the slope steepening, the failure depth increases and slowly changes; when the slope gradient remains between 32.83° (1:1.55) and 34.59° (1:1.45), the damaged depth varies greatly and is within a range of 0.12–0.31 m; hereafter the failure depth almost remains constant with further increases in the slope gradient. So in order to decrease the influence of rainfall on the slope and maintain the stability of the slope affected by the rainfall, it is advisable to control the slope gradient below 32.83° (corresponding slope ratio 1:1.55).

5.1.2 The Effect of Slope Height

To analyze the influence of the slope height on the slope stability during rain, the slope height was classified into five cases as 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 m, and the other conditions are set as described in Sect. 4.1. In Fig. 9, it is shown how \(L/{L_0}\) varies with the slope height after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. \(L/{L_0}\) increases continuously with the slope height’s increase. When the slope height is near 6 m, \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its minimum 0.91 and when the height is 14 m, \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its maximum 0.97. The failure depth of the slope at section “1-1” is also shown in Fig. 9. It varies with the slope height changes after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. The failure depth remains nearly constant, at 0.29 m, whatever the slope height.

5.1.3 The Effect of Horizontal Percolation Properties

The vertical permeability was set as a constant \({K_{11}}=2.81 \times {10^{ - 7}}\)m/s, and the ratio of the horizontal permeability parameter to the vertical one was classified into five cases: \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\)=1, 2, 4, 6, 8. The other conditions are the same as described in Sect. 4.1. The results are summarized in Fig. 10. Figure 10 shows how \(L/{L_0}\) varies with \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. From Fig. 10, it is found that \(L/{L_0}\) changes little with \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\)’s increase. When the \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) is 4, the ratio of \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its maximum, 0.992, and when the \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) is 1, \(L/{L_0}\)reaches its minimum 0.952. Figure 10 shows how the failure depth of the slope at section “1-1” varies with \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. This figure indicates that the failure depth increases and slowly changes with the horizontal permeability parameters’ increase; when the ratio of \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) stays within 4 and 6, the failure depth varies greatly with a range of 0.29–0.44 m. Thus, to decrease the effect of rainfall on the slope’s stability, it is advisable to control the ratio of \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) less than 4.

5.1.4 The Effect of Rain Intensity

The rainfall strength was classified into five cases:R = 100 mm h− 1, t = 3 h; R = 80 mm h− 1, t = 3.75 h; R = 60 mm h− 1, t = 5 h; R = 40 mm h− 1, t = 7.5 h; and R = 20 mmh− 1, t = 15 h, and the other conditions are the same as described in Sect. 4.1. Figure 11 shows the results that how \(L/{L_0}\) varies with changing rainfall intensity under a constant rainfall total. From this figure, it is revealed when R = 100mmh− 1 and t = 3 h, \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its minimum 0.952 and when R = 40 mm h−1, t = 7.5 h, the ratio of \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its maximum 1.0. Figure 11 shows how the failure depth of the slope at section “1-1” varies with the rainfall intensity changing under a constant rainfall in total. According to Fig. 11, one finds that with the rainfall strength decreasing and time extending, the failure depth at section of ‘1-1’ increases; however, when the rainfall intensity R stays between 60 and 100 mm h−1, the failure depth only varies a little and reaches about 0.29 m; when R falls less than 60 mm h−1, the failure depth varies much more, and when R reaches 20 mm h−1, the failure depth is up to 0.55 m.

5.1.5 The Effect of the Initial Saturation of Soil

The initial saturation was classified into five cases: \({S_\omega }=\) 0.35, 0.45, 0.55, 0.65, and 0.75, and the other conditions are the same as described in Sect. 4.1. Figure 12 shows how \(L/{L_0}\) varies with the initial saturation changing after the 3-h-long rainfall intensity of 100 mm h−1. From the figure, one can find that \(L/{L_0}\) does not keep decreasing with the initial saturation increasing, and when the initial saturation reaches 0.55, \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its minimum 0.95; hereafter, \(L/{L_0}\) gradually increases, with small changes. Figure 12 also shows how the failure depth of the slope at the section “1-1” varies with the initial saturation after the 3-h-long rainfall intensity of 100 mm h−1. From this figure, it is demonstrated that the failure depth almost remains a constant as 0.29 m no matter how much the initial saturation is.

5.1.6 The Effect of Compaction

In the process of on-site compaction, the slope edge normally could not be tightly compacted due to the slope edge lacking lateral restraints. To analyze the influence of the compaction of the slope edge on the slope stability during raining, the zone 3 m wide from the slope edge to the slope body was assumed weakly compacted and its compaction coefficient was classified into four cases as 87, 90, 93, and 95%, and other zones of the slope were well compacted and their compaction coefficient was 98%. The other conditions are the same as described in Sect. 4.1. Figure 13 shows how the ratio of \(L/{L_0}\) varies with the compaction coefficient changing after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. From this figure, it is revealed that \(L/{L_0}\) does not keep decreasing with the compaction increasing. When the compaction coefficient reaches 0.95, \(L/{L_0}\) reaches its minimum, 0.96; hereafter, \(L/{L_0}\) gradually increases, with small changes. Figure 13 also shows how the failure depth of the slope at section “1-1” varies with the compaction coefficient changing after the 3-h-long 100 mm h−1 rainfall. The failure depth gradually decreases with increasing compaction coefficient; when the compaction coefficient is 0.87, the failure depth reaches its maximum of 0.39 m and when the compaction coefficient is 0.95, the damaging depth reaches its minimum of 0.17 m.

5.1.7 The Effect of the Long-Term Strength

To analyze the influence of the long-term strength on the slope stability during raining time, the short-term strength parameters were \({C_{\text{s}}}=\)28.76 kPa and \({\phi _{\text{s}}}=23.36^\circ\), and the long-term strength parameters were \({C_{\text{s}}}=\)11.22 kPa and \({\phi _{\text{s}}}=34.01^\circ\) are provided for stability analysis. Other parameters are shown in Table 1, and the rest of the information is the same as in Sect. 4.1. Figure 14 shows the potential failure zones with and without considering the effect of the long-term strength. The curves reveal that if the influence of the long-term strength is neglected, the potential failure zones only develop in the zones from A to D and B to D, but if the effect of the long-term strength is considered, the potential failure zones will run through from the slope toe to the slope top, almost parallel to the slope surface, and they will develop in the zones of 0.3 m deep below the slope surface.

5.2 A Brief Discussion on Sensitivity

The slope stability is determined by many factors. The higher the value of \(L/{L_0}\), the more serious the failure; the deeper the failure, the more serious the failure. The results of the analysis indicate that three factors, rainfall intensity, its duration, as well as the long-term strength are the ones most influencing he slope stability. Thus, for a real engineering practice, attention is suggested to be more paid on the influences of these three factors.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, the constitutive model of two-phases coupling of unsaturated water and air has been established based on the single variable effective stress theory of unsaturated soil. With the consideration of the fluid–solid coupling of surface runoff and underground infiltration, the theoretical calculating model has been numerically verified by the engineering case analysis of rainfall-caused slope failure within the part of K240 + 10 and K240 + 70 on the Dazhou-Chengdu Railway Line. The numerical calculation and analysis have been conducted for each main factor that may significantly influence the slope stability. The following conclusions have been obtained:

-

1.

The consideration of fluid–solid coupling of surface runoff and underground infiltration is necessary for the analysis of slope stability. Only in this way can the process of rainfall affecting the slope, as well as the gradual failure process of slope can be revealed accurately. The proposed coupling model is reliable to analyze such coupling effect for slope engineering under rainfall.

-

2.

In order to decrease the effect of rainfall on the slope stability, the whole slope surface should be protected, the slope ratio of 1:1.55 is suggested, the ratio of \({K_{11}}/{K_{22}}\) should be less than 4, the reinforcing depth in the slope should reach about 0.5 m and the compaction coefficient of the embankment slope should be increased as possible;

-

3.

Whatever the slope height and the soil’s initial saturation are, the slope stability under rainfall is little affected by them. Under the conditions of the same rainfall totals, when rainfall strength is below 60 mm h−1 the change of the rainfall intensities has a large influence on the slope stability, whereas when the rainfall intensities are larger than this value, the influence of the variation of the rainfall intensities on the slope stability is relatively much less;

-

4.

Putting together the influences of all factors, the rainfall intensity, the duration, as well as the long-term strength of the soil has the most notable influence on the slope stability under raining conditions.

Abbreviations

- \({u_{\text{a}}} - {u_{\text{w}}}\) :

-

Matrix suction

- \(n\) :

-

Coefficient of roughness

- \(g\) :

-

Acceleration of gravity

- \(u\) :

-

Velocity of the flow

- \(q\) :

-

Water flow volume rate

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Slope angle

- \(\beta\) :

-

Rainfall direction

- \(I\) :

-

Rainfall intensity

- \({S_{\text{a}}}\) and \({S_{\text{w}}}\) :

-

Mean saturation of air and water

- \({H^{\text{a}}}\) and \({H^{\text{w}}}\) :

-

Air head and water head

- \({q_{\text{a}}}\) and \({q_{\text{w}}}\) :

-

The sources of air and water

- \({\rho _{\text{a}}}\) and \({\rho _{\text{w}}}\) :

-

Densities of air and water

- \(\mu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity

- P :

-

Pore pressure

- \(\xi\) :

-

Fluid volume change

- \({q_{\text{v}}}\) :

-

Volume strength of the fluid source

- \({K_{\text{w}}}\) and \({K_{\text{a}}}\) :

-

Bulk modulus of fluid and air

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Volumetric strain

- \(\rho\) :

-

Volume density

- \(\Delta \sigma ^{\prime}_{{ij}}\) :

-

Change of the effective stresses

- \(\kappa\) :

-

Parameter of stress-paths.

- H :

-

The constitutive law’s functional form

- \({C_{\text{S}}}\) :

-

Cohesion strength

- \({\phi _{\text{S}}}\) :

-

Internal friction angle

- \({\sigma '_1}\) :

-

The maximum principal effective stresses

- \({\sigma '_3}\) :

-

The minimum principal effective stresses

- \(FOS\) :

-

Factor of safety

References

Pan M, Li TF (2002) Catastrophic geology. Beijing Publishing Group LTD, Beijing, pp 40–50 (Chinese)

Yu FC, Chen TC, Lin ML, Chen CY, Yu WH (2006) Landslides and rainfall characteristics analysis in taipei city during the typhoon nari event. Nat Hazards 37(1–2):153–167

Farah K, Ltifi M, Abichou T et al (2014) Comparison of some probabilistic methods for analyzing slope stability problem[J]. Int J Civil Eng 12(3):452–456

Tsaparas I, Rahardjo H, Toll DG, Leong EC (2002) Controlling parameters for rainfall-induced landslides. Comput Geotech 29(1):1–27

Zhang LL, Zhang J, Zhang LM, Tang WH (2011) Stability analysis of rainfall induced slope failure: a review. Geotech Eng 164(5):299–316

Tung YK, Kwok YF, Ng CWW, Zhang H (2011) A preliminary study of rainfall infiltration on slope using a new coupled surface flow model. Rock Soil Mech 25(9):1347–1352

Liu X, Sheng K, Hua JH et al (2015) Utilization of high liquid limit soil as subgrade materials with pack-and-cover method in road embankment construction[J]. Int J Civil Eng 13(3B):167–174

Wang JX, Wang EZ, Wand SJ (2010) Potential description of rainfall free infiltration phase. J Tsing hua Univ 50(12):1920–1924

Chen S.Y (1997) A method of stability analysis taken effects of infiltration and evaporation into consideration for soil slopes. Rock Soil Mech 18(2):8–13. (in Chinese)

Gasmo JM, Rahardjo H, Leong KC (2000) Infiltration effects on stability of a residual soil slope. Comput Geotech 26(2):145–165

Wang XF (2003) Study of effects of rain infiltration on stability of unsaturated slopes, MS Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, pp 6–31 (in Chinese)

Ng CWW, Zhan LT, Bao CG, Fredlund DG, Gong BW (2003) Performance of an unsaturated expansive soil slope subjected to artificial rainfall infiltration. Geotechnique 53(2):143–157

Zhang PW (2002) Study of coupling numerical simulation of saturated-unsaturated soil under rainfall conditions, PhD Thesis, Institute of Civil Engineering and Architecture. Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, p 76 (Chinese)

Vieira CS (2014) A simplified approach to estimate the resultant force for the equilibrium of unstable slopes. Int J Civil Eng 12(1):65–71

Wang XQ, Zhang YX, Zou WL, Xing HF (2010) Numerical simulation for unsaturated road-embankment deformation and slope stability under rainfall infiltration. Rock Soil Mech 31(11):3640–3655 (in Chinese)

Santoso AM, Phoon KK, Quek ST (2001) Effects of soil spatial variability on rainfall-induced landslides. Comput Struct 89(11/12):893–900

Madhav V (2010) Slope stability analysis of basal reinforced embankment under oblique pull[J]. Int J Civil Eng 1(1):01–14

Wong TT, Fredlund DG, Krahn J (1998) Numerical study of coupled consolidation in unsaturated soils[J]. Can Geotech J 35(12):926–937

Xu H, Zhu YW, Cai YQ, Zhu FM (2005) Stability analysis of unsaturated soil slopes under rainfall infiltration. Rock Soil Mech 26(12):1957–1962 (in Chinese)

Afshar JN, Ghazavi MA (2014) simple analytical method for calculation of bearing capacity of stone-column. Int J Civil Eng 12(1):15–25

Heidarzadeh M, Mirghasemi AA, Niroomand H (2015) Construction of relief wells under artesian flow conditions at dam toes: engineering experiences from Karkheh earth dam, Iran. Int J Civil Eng 13(1):73–80

Mir BA (2015) Some studies on the effect of fly ash and lime on physical and mechanical properties of expansive clay. Int J Civil Eng 13(3):203–212

Liu X, Sheng K, Hua JH, Hong BN, Zhu JJ (2015) Utilization of high liquid limit soil as subgrade materials with pack-and-cover method in road Embankment construction. Int J Civil Eng 13(3):167–174

Yildiz A, Uysal F (2016) Modelling of anisotropy and consolidation effect on behaviour of sunshine embankment: Australia. Int J Civil Eng 14(2):83–95

Dai FU, Lee CF, Wang SJ (1999) Analysis of rainstorm induced slide-debris flows on natural terrain of Lantau Inland, Hong Kong. Eng Geol 51:279–290

Huang CC, Yuin SC (2010) Experimental investigation of rainfall criteria for shallow slope failures. Geomorphology 120:326–338

Lin HD, Kung JHS (2000) Rainfall-induced slope failures in Taiwan, Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Unsaturated Soils, Singapore, pp 801–806

Qi H, Gantzer CJ, Jung PK, Lee BL (2000) Rainfall erosivity in the Republic of Korean. J Soil Water Conserv 55(12):115–120

Lin P, Zhao SJ, Li A, Li MH (2002) Effect of infiltration into cliff debris on the stability of slope. Geotech Investig Surv 1:26–28 (in Chinese)

Gao XY, Liao HJ, Ding CH (2002) Seepage effects on soil slope stability. Rock Soil Mech 25(1):69–72 (in Chinese)

Lin HC, Li GX, Yu YZ, Lu H (2007) Influence of matrix suction on shear strength behavior of unsaturated soils. Rock Soil Mech 28(9):1931–1936 (in Chinese)

Ng CWW, Chen SY, Pang YW (1999) Parametric study of effects of rain infiltration on unsaturated slopes. Rock Soil Mech 20(1):1–14 (in Chinese)

Itasca Consulting Group Inc (2005) Fast Lagrangian analysis of continua in two-dimensions, version 5.0 user’s manual: two-phase flow. Itasca Consulting Group Inc, Minneapolis, pp 1–12

Wen K, Jin GS, Li Q (1990) Numerical simulation of surface flow process. China Hydraulic and Electric Power Publishing House, Beijing, p 320

Engman ET (1976) Roughness coefficient for routing runoff. Irrig Drain Eng ASCE 112(1):39–54

Hutter K, Laloui L, Vulliet L (1993) Thermodynamically based mixture of saturated and unsaturated soils. Proc Mech Cohes Frict Mater 4(4):295–338

Schrefler BA, Zhan XY (1993) A full coupled model for water flow and air flow in deformable porous media. Water Resources Res 29:55–167

Liu JX (2007) Study on stability of embankments of red layers subjected to unsaturated seepage. PhD Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu (in Chinese)

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the Emergency Management Project of the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC)(No. 41641023), and the Science and technology support and International Cooperation Project (No. 2016GZ0157) of Sichuan, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Yang, C., Gan, J. et al. Stability Analysis of Road Embankment Slope Subjected to Rainfall Considering Runoff-Unsaturated Seepage and Unsaturated Fluid–Solid Coupling. Int J Civ Eng 15, 865–876 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-017-0194-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-017-0194-7