Abstract

This paper uses peer comparisons to analyze the impact of different types of inequalities (i.e., within-group, between-group and overall inequality) and reference income on subjective happiness. This study contributes to an emergent strand of research in which both relative levels of economic resources and the income distribution are regarded as determinants of individual happiness. The empirical findings show that overall and within-group inequality negatively affect individual happiness, inequality between reference groups does not affect happiness, and a higher average income of the reference group increases individual happiness. We examine whether people’s aversion to inequality is conditional on their income position within reference group and institutional differences across European countries. These tests indicate that an increase in inequality or a decrease in average income decreases the happiness of both the rich and the poor. Regarding the differences across countries, people who live in more mobile societies with better welfare systems (e.g. Social-Democratic countries) are less adversely affected by inequality than people living in countries with low social mobility and ineffective systems of social protection (e.g. the Mediterranean countries). The analysis is based on data from the European Quality of Life Survey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kahneman (1999), Frey and Stutzer (2004) and Gruber and Mullainathan (2005) are several of the most explicit analyses of the relationship between happiness and utility. See Kimball and Willis (2006) for a discussion of the similarities and differences between utility and happiness. As is common in this literature (e.g., Frey and Stutzer 2000), this paper uses the term “happiness” interchangeably with the terms “satisfaction with life” and “subjective well-being” for the sake of simplicity.

See Alvarez-Cuadrado and Ngo (2012) for a theoretical model of the impact of positional concerns regarding the income distribution.

Corak (2013) provides possible support for the hypothesis that Mediterranean and Social-Democratic countries are on the opposite sides of a European ranking based on social mobility. In his classification of intergenerational earnings mobility, Scandinavian countries emerge as the most mobile societies, while a “Mediterranean” country (Italy) occupies the worst position among the European countries. Again, countries such as Germany and France, for which we obtain mixed results, also occupy intermediate positions in Corak’s ranking.

Falk and Knell (2004) present a theoretical model in which the reference group is endogenous.

Educational attainment is considered preferable to other traits (e.g., income or marital status) because, although education attainment may be affected by student happiness, and both of them can be affected by the same genetic traits, we believe that among the other potential endogenous criteria for clustering, educational attainment is both reasonably stable during adult life and also able to control for other factors that are not directly observable in our dataset (e.g., an individual’s skills, family background).

To ensure that the results are robust to outliers and to make reliable estimates within reference groups, we fix a threshold of the minimum reference group size at 50 individuals. Accordingly, the number of reference groups decreases from the potential (3 × 4 × 3 × 30 =) 1080 to 771, because 309 reference groups contain fewer than 50 individuals. These exclusions also decrease the total sample size by 8.97% (i.e., from 81,060 to 73,786). However, we find that the results are robust to other minimum thresholds (e.g., 20). We also define reference groups further in terms of gender. Although the results are qualitatively the same, the total sample size decreases by 39.77% (i.e., from 73,786 to 44,440) and generates sample bias because the excluded reference groups are concentrated in small countries. That is, we opt to omit gender as a criterion to define a reference group. These robustness checks are available on request from the corresponding author.

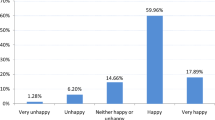

The EQLS happiness question is as follows: Q41: Taking all things together on a scale of 1–10, how happy would you say you are? Here, 1 means you are very unhappy and 10 means you are very happy.

It measures an individual’s real access to economic resources and is usually considered a key determinant of happiness because it is required to meet basic needs. The income used in this analysis is the monthly net household income converted through the OECD equivalence scale. It assigns a value of 1 to the first adult in the household, 0.5 to each remaining adult, and 0.3 to each child. The adjective “real” means that income is converted into euros as of the year 2000. This transformation makes comparable individual income given differences in household size and economies of scale, currencies and inflation rates across waves and countries.

The generalized entropy class of indices is a decomposable class of income inequality measures that are sensitive to a parameter a. If a is close to zero, the index is more sensitive to changes at the lower end of the distribution; it is equally sensitive to changes across the distribution for a=1 (Theil index), and it is sensitive to changes at the higher end of the distribution for higher values (Shorrocks 1984). Moreover, the three parameterizations of a are special cases of income inequality metrics; in particular, Ge(0) is the mean log deviation, Ge(1) is the Theil index, and Ge(2) is half the squared coefficient of variation.

Because Gini is not a decomposable measure of income inequality, we do not report this index.

The countries are grouped by extending the classification of welfare systems, as proposed by Esping-Andersen (1990), Ferrera (1996) and Fenger (2007), as follows: Mediterranean (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Spain, Turkey); Conservative (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands); Social-Democratic (Denmark, Finland, Sweden); Liberal (Ireland, the UK); CEE (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Rep., Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia).

However as a robustness check, we also estimated all the regressions by Ordered Probit, and no relevant differences in coefficients or significance were observed.

These broad definitions of “rich” and “poor” allow us to maintain the sample size.

Note that in a benchmark regression with only controls (see Table 8 in Appendix 2), education levels positively affect individual happiness; however, these effects became statistically insignificant when we include in the model specification indexes of income inequality or a measure of relative income.

We address this caveat by clustering standard errors at the level of reference groups.

An alternative rationale for this result is also possible: in countries with inadequate social mobility (e.g., Mediterranean countries), higher inequality means that economic disparities will remain wide in the future; thus, given that inequality is a form of income concentration, the poor are more numerous than the rich, and thus, the estimated overall effect is guided by the disadvantageous prospects for poor peoples’ incomes, namely, they are likely to continue to be poor in the future \( (\beta_{1}^{Med} < 0) \). Otherwise, in more mobile societies or those with generous welfare systems, income inequality does not affect individual happiness because the overall effect, which is always led by the poor, indicates a greater likelihood that their position in the economic ranking could change in the future.

With exclusion of model IV.6, where \( \alpha_{1}^{{\left( {P - R} \right)}} > 0 \).

This result does not hold for \( P_{i}^{j} \sigma_{j}^{whitin} \), which exhibits statistical significance at the 5% level. However, when we apply the Probit estimator, this coefficient is no longer statistically significant (p value 0.196).

This result does not support the findings of Satya and Guilbert (2013), which are based on Australian data. In their research, an increase in peer group income harms the poor more than the rich.

Alternatively, we could assume that these two opposite effects occur but cancel one another out.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2005) appears to indirectly validate this supposition, since her estimates on Germany change sign and statistical significance when the full sample is split between East and West Germany.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (2001). Why doesn’t the United States have a European-style welfare state? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 187–277.

Alvarez-Cuadrado, F., & Ngo, V. L. (2012). Envy and inequality. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 114, 949–973.

Angeles, L. (2010). Adaptation or social comparison? The effects of income and happiness. Scottish Institute for Research in Economics (SIRE) SIRE Discussion Papers 2010-03.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Argyle, M. (1999). Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 353–373). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bárcena-Martín, E., Cortés-Aguilar, A., & Moro-Egido, A. I. (2016). Social comparisons on subjective well-being: The role of social and cultural capital. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9768-3.

Barro, R. J. (2000). Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. Journal of Economic Growth, 5(1), 5–32.

Bartolini, S., Bilancini, E., & Sarracino, F. (2013). Predicting the trend of well-being in Germany: How much do comparisons, adaptation and sociability matter? Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 169–191.

Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In B. Greve (Ed.), Happiness and social policy in Europe (pp. 174–194). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Blanchflower, D.G., & Oswald, A.J. (2003). Does inequality reduce happiness? Evidence from the States of the USA from the 1970s to the 1990s, paper presented at the conference “The Paradoxes of Happiness in Economics”, Milan.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2011). International happiness, NBER Working Papers 16668, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Bourguignon, F. (1999). Comment on ‘Multidimensioned approaches to welfare analysis’. In E. Maasoumi & J. Silber (Eds.), Handbook of income inequality measurement (pp. 477–484). Boston: Kluwer.

Cameron, C., & Miller, D. L. (2010). Robust inference with clustered data, Working Papers 107. Davis: Department of Economics, University of California.

Clark, A. (2003). Inequality-aversion and income mobility: A direct test. Mimeo. Paris: DELTA.

Clark, A. E., & D’Ambrosio, C. (2015). Attitudes to income inequality: Experimental and survey evidence. In A. Atkinson & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2A). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61, 359–381.

Corak, M. (2013). Inequality from generation to generation: The United States in comparison. In R. Rycroft (Ed.), The economics of inequality, poverty, and discrimination in the 21st century. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Corcoran, K., Crusius, J., & Mussweiler, T. (2011). Social comparison: Motives, standards, and mechanisms. In D. Chadee (Ed.), Theories in social psychology (pp. 119–139). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Delhey, J., & Dragolov, G. (2014). Why inequality makes Europeans less happy: The role of distrust, status anxiety, and perceived conflict. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 151–165.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 851–864.

Diener, E. D., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 27, 35–47.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fahey, T., & Smyth, E. (2004). The link between subjective well-being and objective conditions in European societies. In W. A. Arts & L. Halman (Eds.), European values at the turn of the millennium (pp. 57–80). Leiden: Brill.

Falk, A., & Knell, M. (2004). Choosing the Joneses: On the endogeneity of reference groups. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106, 417–435.

Fenger, H. J. M. (2007). Welfare regimes in Central and Eastern Europe: Incorporating post-communist countries in a welfare regime typology. Contemporary Issues and Ideas in Social Sciences, 3(2), 1–30.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The “southern model” of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 997–1019.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Ramos, X. (2010). Inequality aversion and risk attitudes, SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research 271. DIW Berlin: The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Ramos, X. (2014). Inequality and happiness. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(5), 1016–1027.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic Journal, 110, 918–938.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect well-being. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Economic consequences of mispredicting utility. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 937–956.

Goerke, L., & Pannenberg, M. (2013). Direct evidence on income comparisons and subjective well-being, IAAEU Discussion Papers 201303. Institute of Labour Law and Industrial Relations in the European Union.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4, 107–122.

Gruber, J., & Mullainathan, S. (2005). Do cigarette taxes make smokers happier? The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 1(5), 1–45.

Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators Research, 75(2), 169–216.

Helliwell, J. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20(2), 331–360.

Helliwell, J., & Huang, H. (2008). How’s your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. British Journal of Political Science, 38, 595–619.

Hirschman, A. O., & Rothschild, M. (1973). The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4), 544–566.

Johns, H., & Ormerod, P. (2008). Happiness, economics and public policy. London, UK: The Institute of Economic Affairs.

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology, chapter 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kimball, M. S., & Willis, R. (2006). Utility and happiness. Working paper, University of Michigan, Michigan, MI.

Knight, M., Seymour, T. L., Gaunt, J. T., Baker, C., Nesmith, K., & Mather, M. (2007). Aging and goal directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion, 7, 705–714.

Layard, R. (2006). Happiness and public policy: A challenge to the profession. The Economic Journal, 116, C24–C33.

Layte, R. (2012). The association between income inequality and mental health: Testing status anxiety, social capital, and neo-materialist explanations. European Sociological Review, 28(4), 498–511.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 963–1002.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56, 239–249.

McBride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45, 251–278.

Morawetz, D., Atia, E., Bin-Nun, G., Felous, L., Gariplerden, Y., & Harris, E. (1977). Income distribution and self-rated happiness: Some empirical evidence. The Economic Journal, 87(347), 511–522.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100.

Ott, J. (2005). Level and inequality of happiness in nations: Does greater happiness of a greater number imply greater inequality in happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 397–420.

Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 51, 29–49.

Rözer, J., & Kraaykamp, G. (2013). Income inequality and subjective well-being: A cross-national study on the conditional effects of individual and national characteristics. Social Indicators Research, 113, 1009–1023.

Satya, P., & Guilbert, D. (2013). Income–happiness paradox in Australia: Testing the theories of adaptation and social comparison. Economic Modelling, 30, 900–910.

Schepers, J. (2015). On regression modelling with dummy variables versus separate regressions per group: Comment on Holgersson et al. Journal of Applied Statistics, 43(4), 674–681.

Schneider, S. M. (2016). Income inequality and subjective wellbeing: Trends, challenges, and research directions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 1719–1739.

Schwarze, J., & Härpfer, M. (2007). Are people inequality averse, and do they prefer redistribution by the state? Evidence from German longitudinal data on life satisfaction. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 36, 233–249.

Schyns, P. (2002). Wealth of nations, individual income and life satisfaction in 42 countries: A multilevel approach. Social Indicators Research, 60, 5–40.

Senik, C. (2004). When information dominates comparison. Learning from Russian subjective panel data. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2099–2123.

Senik, C. (2009). Income distribution and subjective happiness: A survey. OECD Social, Employment and Migration, Working Papers, 96.

Shorrocks, A. F. (1984). Inequality decomposition by population subgroups. Econometrica, 52, 1369–1388.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 39(1), 1–102.

Thurow, L. (1971). The income distribution as a pure public good. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 83, 327–336.

Tomes, N. (1986). Income distribution, happiness and satisfaction: A direct test of the interdependent preferences model. Journal of Economic Psychology, 7, 425–446.

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Apparent quality-of-life in nations: How long and happy people live. Social Indicators Research, 71, 61–86.

Vendrik, M., & Woltjer, G. (2007). Happiness and loss aversion: Is utility concave or convex in relative income? Journal of Public Economics, 91, 1423–1448.

Verme, P. (2011). Life satisfaction and income inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(1), 111–137.

Wooldrige, J. (2006). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Yamada, K., & Sato, M. (2013). Another avenue for anatomy of income comparisons: Evidence from hypothetical choice experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 89(C), 35–57.

Yamada, M., & Takahash, H. (2011). Happiness is a matter of social comparison. Psychologia, 54, 252–260.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank anonymous reviewers for providing insightful comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors or inaccuracies are, of course, our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

The econometric analysis is based on three cross-sections (waves 2007, 2011 and 2016) of the Integrated European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) dataset.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2018). European Quality of Life Survey Integrated Data File, 2003–2016 [data collection], 3rd Edition. UK Data Service, SN: 7348. http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7348-3

The original dataset collects variables at the individual level for 31 countries (27 EU Member States, Croatia, FYR Macedonia, Turkey and Norway) in the 2007 wave, 34 countries (27 EU Member States and Croatia, Iceland, FYR Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey and Kosovo) in the 2011 wave; and 33 countries (28 EU Member States and Albania, FYR Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey) in the 2016 wave. We include only the 30 countries surveyed in all the three selected waves: the EU 28, FYR Macedonia and Turkey. The survey is publicly available, and all the information can be found on the EQLS website (http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys-eqls).

Appendix 2: Control variables

In this appendix we show the estimates of control variables for Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 in Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11, respectively.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amendola, A., Dell’Anno, R. & Parisi, L. Happiness and inequality in European countries: is it a matter of peer group comparisons?. Econ Polit 36, 473–508 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0130-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0130-6