Abstract

Purpose

Earlier studies tried to predict and explain adult-onset offending, most often by comparing risk factors for juvenile and adult onset of criminal behavior. Little is known, however, about how criminal careers of adult-onset offenders develop. The aim of this study is to describe and compare juvenile- and adult-onset criminal careers of both men and women in terms of frequency, intensity, duration, recidivism, crime mix, seriousness, and specialization.

Methods

Using a sample of 43,338 offenders who all had a criminal record in 2013, criminal careers are reconstructed retrospectively up to age 12 and prospectively up to the 1st of July, 2014. Male and female juvenile- and adult-onset offenders are identified and compared on the abovementioned parameters of their criminal careers.

Results

Compared to all other groups, female adult-onset offenders commit fewer crimes, offend at a lower rate, desist from crime earlier, have lower recidivism risks at least up to the tenth crime, commit different types of offenses, commit more minor and less serious crimes, and are more specialized in the types of crime they commit. Male juvenile-onset offenders have the most serious career in terms of these career dimensions.

Conclusions

Criminal careers of adult-onset offenders, both men and women, develop differently on all dimensions. Implications for life-course criminological theories and prevention strategies are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crime onset is a critical component of criminal careers as it might give insight into the causes of crime. Onset is the moment at which individuals show discontinuity in their behaviors for the first time; they make a transition from non-offender to offender. Most life-course studies have traditionally focused on the onset of criminal behavior and its correlates in children and adolescents [18, 40]. The advent of the group-based trajectory methodology [43] enhanced the attention for other, less traditional, crime patterns such as a delayed start of offending. For some individuals, criminal behavior was found only to unfold later on in life.

Some scholars question the existence of true adult-onset offenders (onset at or after age 18) and argue that adult onset in crime is so rare that it does not deserve research attention at all [42]. Others contend that adult-onset offenders are an artifact of the use of register data and that adult-onset offenders have most characteristics in common with early-onset offenders [51, 70]. Over the last years, however, the study of adult-onset offending has multiplied and provided evidence that “offending is not predominantly a teenage phenomenon” ([14], p. 235), there is “a non-negligible amount of adult onset” ([22], p. 523), “evidence is mounting that late criminal onset exists, and that it can be predicted early in the life course” ([73], p. 297). DeLisi and Piquero [8] identified this understudied group of offenders as an important research gap in life-course criminology that deserves serious research attention in the future. Also, more recently, Sapouna [56] endorsed this argument by stating that “there is a non-negligible proportion of adult-onset offenders that merits further research”.

Earlier studies have tried to predict and explain adult-onset offending, most often by comparing risk factors for an early and adult onset of criminal behavior (e.g., [1, 11]). It was found that several correlates do predict early-onset offending but do not relate to adult-onset offending or vice versa (e.g., [10, 22, 35, 73, 74]). It was to a lesser extent studied, however, how criminal careers of adult-onset offenders develop. While other studies tried to identify psychological or criminogenic correlates of a criminal onset, this study will rather describe and compare criminal patterns of men and women with a juvenile or an adult onset. It contributes to the existing knowledge because it is the first to systematically describe a large set of criminal career dimensions for those with a delayed onset. Not only will main components to the criminal career paradigm—participation, frequency, seriousness, and career length—be analyzed, recidivism, crime mix, seriousness of crimes, and specialization in types of crime will also be examined. Findings for adult-onset offenders will be discussed in comparison to those for juvenile-onset offenders. Moreover, all analyses will be gender-specific, allowing for comparisons between male and female juvenile- and adult-onset offenders.

Theoretical Views on the Prevalence of Adult-Onset Offending

As early as 1986 [5], Blumstein and colleagues recognized that not all offenders start early and estimated that four to five out of ten adult offenders do not have juvenile records. Eggleston and Laub [11] confirmed the existence of those with a delayed onset and challenged Moffitt et al. [42] by stating that “adult onset was not a rare event” in their study. Up to date, however, it is unclear how large this group is and how their behavior evolves.

Adult-onset offenders are disregarded by propensity and control theories, which predominantly explain criminal behavior by a relatively stable underlying trait. According to such theories, individuals with certain characteristics are predisposed to engage in crime [23, 41, 51]. This propensity for offending is more or less constant over time and therefore, “adult antisocial behavior virtually requires childhood antisocial behavior” ([51], p. 611).Footnote 1 The only explanation, according to this theory, for official adult-onset offending is that prior offending (before age 18) simply has gone undetected and therefore adult onset is an artifact of the use of register data. Following this argument, Moffitt et al. [42] argue that the “onset of antisocial behavior after adolescence is extremely rare.” The traditional distinction of adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent offenders does not allow for a delayed onset, i.e., after the age of 18 [41]. Also, more recently, it was argued by Beckley et al. [2] that the amount of adult-onset offending is unremarkable and that, if existing at all, it can be explained in the same way early-onset offending is explained.

Another line of reasoning is followed by dynamic life-course theories, explaining delinquent and criminal behavior not only by personal characteristics but also by the settings and opportunities for crime. Such theories allow for individual change in offending at all times during the life course. Adult-onset offending is explained in different, but related, ways by several dynamic theories. In their age-graded theory of informal social control, Sampson and Laub [55] focus on the strength of bonds to society, such as attachment to parents, (delinquent) friends, school, work, and supervision by parents or others. Changes over time in the strength of these bonds, whether or not as a result of significant life events, can result in a turning point in behavior and alter an individual’s choices. Individuals earlier engaged in crime can desist from crime as a result of a positive life event (e.g., getting a job, marriage, becoming a parent), but a negative life event (e.g., losing a job, divorce) can just as well be a stimulus to engage in crime for individuals who have never engaged in crime before [53]. Individuals with strong social bonds during childhood and adolescence may make the transition to crime when these bonds weaken during the transition to adulthood or later in adulthood and therefore, adult-onset offending is explained by transitions in adult life circumstances [54].

From an interactional perspective, different factors explain crime onset at different ages [64]. Important factors explaining an onset in early childhood (before age 6), for example, are neuropsychological deficits and poor parenting. Individuals starting to offend in later childhood (6–12 years) are influenced by their family and neighborhood, while adolescent-onset offenders (12–18 years) act on the influence of their peers. According to Thornberry and Krohn [64, 63], adult-onset offenders share individual and psychological deficits with their early-onset counterparts, but differ from early-onset offenders in that they had a supporting (family) environment that prevented them from involvement in crime during childhood and adolescence. When individuals with such strong ties make the transition to adulthood and independence, their buffer disappears, and they are incapable of managing higher education or a job. They are unable to cope with the demands of adult life without the support of their family and as a result, they seek for a solution in crime. Adult-onset offending then is explained by strong family ties that accounted for inhibition of antisocial behavior in the early years and the difficult transition to adulthood when protective factors fade away.

To summarize, traditional propensity theories consider adult-onset offending non-existent or extremely infrequent and are not able to explain adult-onset offending other than as being an artifact of measurement. More recent perspectives take a dynamic or interactional approach by accounting for change in behavior due to changed propensity or opportunities, thereby offering support for the existence adult-onset offending.

Empirical Evidence on the Prevalence of Adult-Onset Offending

Table 1 gives an overview of all known studies that described an offender sample based on register data (police contacts, arrests, and convictions), followed individuals into adulthood, and reported—or presented information enabling the inference of—the proportion of individuals with an official crime onset at or after age 18 (in some studies, adult-onset is defined as 20 or 21 years and older at first conviction).Footnote 2 Excluded are studies on special offender groups, such as samples of frequent or psychiatric offenders (e.g., [12, 50]) and samples that do not reflect a randomly selected sample from a population of individuals or offenders (e.g., [52]). The study conducted by Glueck and Glueck [21], for example, is excluded because two groups of individuals were selected for this study based on whether they committed crimes as juveniles. Therefore, there is no offender group representing the population from which a proportion of adult-onset offenders can be derived. Lastly, studies that used trajectory modeling to identify adult-onset offenders are excluded from the table (e.g., [35]). Trajectories are an approximation of a more complex underlying distribution and not all individuals perfectly fit the trajectory they are classified to; instead, their crime pattern fits that trajectory best [44]. Therefore, it is likely that some of those classified into an adult-onset trajectory, in fact, committed their first crime before age 18.

In all 28 remaining longitudinal studies, evidence was found for the existence of adult-onset offenders, although numbers vary from 9 to 72% of all offenders (Table 1). On average, 39% of the offenders had an adult onset in these studies (median is 38%). In 16 out of 28 studies, more than one third of the sample consists of adult-onset offenders. The wide range of proportions is most likely due to methodological heterogeneity in the sampling procedures of the different studies (see also [2]). Samples used in these studies range from 93 to 40,523 offenders, vary widely in the proportions of males and females included (63 to 100% is male), use different definitions of offending, and differ in follow-up from age 21 to age 72. The broader offending is defined, the earlier crime onset takes place and the less adult onset was found. Secondly, time windows should be wide enough to identify adult-onset offenders in the first place, and to follow their behavioral pattern over time and proportions of adult-onset offenders are likely to rise as individuals are followed for longer periods.

Boys or men are generally found to engage in delinquent behavior at earlier ages than women [50]. It is therefore not surprising that adult-onset offending is most often found to be more prevalent in women than men [2, 4, 11, 25, 28, 34, 45, 57, 59]. As can be seen in Table 1, proportions of adult-onset offenders among male offenders are between 9 and 72% (M = 38%), proportions are between 7 and 90% for females (M = 48%). Some studies, however, found men to be more likely to experience an adult crime onset than women [6, 62, 65, 68]. In other studies, no significant differences were found between men and women in relationship to the amount of adult-onset offending [11, 69].

Official and Self-Reported Adult-Onset Offending

Since most longitudinal studies of crime rely on official data, onset ages reflect behavior that is observed by the authorities and is prohibited by law. Official adult-onset offenders may, therefore, have expressed delinquent behavior before that has gone undetected or was not severe enough to lead to arrest or conviction. Not all criminal behavior is detected, not all detected crime is prosecuted, and not all prosecuted criminals are convicted. Therefore, it is likely that at least some official adult-onset offenders have an unofficial history of criminal behavior [2, 38]. As a result of detection effects in register data, onset age—and the amount of adult-onset offending—to a certain extent is overestimated.

At the same time, other processes may lead to an underestimation of onset age. Firstly, offenders of varying ages have unequal probabilities to get arrested. Older offenders tend to commit offenses with a lower likelihood of detection than younger offenders [38]. Furthermore, it has been found that age in itself affects the chance of arrest. Individuals of different ages receive different levels of official control from the authorities, resulting in a specific bias towards younger individuals [7]. Secondly, study samples often only follow individuals up to a certain age, not covering the total life of individuals. Proportions of adult-onset offenders are likely to increase as individuals are followed up for longer periods (see also [6]). Studies that only have data available up to age 25, for example, miss out on individuals starting to commit crime after that age, lowering the proportion of adult-onset offenders. As a result of judicial selectivity and research samples, onset age—and the amount of adult-onset offending—to a certain extent is underestimated.

These factors influencing under- and overestimation of adult-onset offending are best shown by the study of Zara and Farrington [73, 74]. Based on official records from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (CSDD), they identified 38 late starters (first conviction at age 21 or later), 129 early starters (first conviction before age 21), and 236 non-offenders. Based on these official records, 22.8% of the offenders had an adult onset (38 / (38 + 129)). For all 403 men, Zara and Farrington also had available self-reported information on offending. From the official non-offenders, 16 self-reported offenses in adulthood and eight self-reported offenses before age 18. Out of 38 official late starters, three self-reported offending before age 21. Adjusted for self-reported offending, 51 men had an adult onset (38 + 16 − 3), 140 had an early onset (129 + 8 + 3), and 212 never offended (236 − 16 − 8). Both the group of adult-onset and early-onset offenders became larger after adding information obtained from the individuals themselves. Based on a combination of official and self-reported offenses, 26.7% of the offenders had an adult onset. This shows that, at least in this study, the underestimation of adult-onset offending due to official non-offenders committing crimes in adulthood is larger than the overestimation of adult-onset offending due to undetected crimes before age 18 by official adult-onset offenders.

Other studies containing both official and self-reported measures of offending confirm that self-reported adult-onset offending exists. Lay et al. [29] used a combination of officially recorded and self-reported crime to identify adult-onset offenders in a sample of 321 8-year-olds with behavioral problems followed up to age 25. Using this approach, they identified 45 offenders out of a total of 93 offenders (48%) who were convicted or self-reported crime only during adulthood. Should they have considered official records, only 12 individuals would have been identified as adult-onset offenders (13%). Thus, similar to studies conducted by Zara and Farrington [73, 74], adult onset is not only overestimated by official records, but self-reports also reveal offenders who start committing crime later on in life who would have been classified as non-offender by official data. It was found in studies comparing register data with self-reported information on criminal behavior that a time gap of 3 to 5 years exists between the first self-reported crime and the first official crime onset [27, 30, 33, 42, 61].

Dimensions of Adult-Onset Offending Careers

Although adult-onset offenders are disregarded by some scholars (e.g., [42]), the studies presented in Table 1 show ample evidence of at least a substantial proportion of adult-onset offenders among general offenders samples. Up to date, however, juvenile-onset offending received overpowering research attention while still little is known on those with a later onset in crime. While the correlates of adult-onset offending received more and more attention during the past years, the study of adult-onset offending has to a lesser extent focused on the criminal patterns that follow a crime onset at a later age, although several studies touched upon several criminal career parameters [6, 19, 38]. Some expectations can be derived from these earlier studies and from general conclusions on the relationship between onset age and criminal career characteristics.

Frequency, Intensity, and Duration

It was often found that an earlier onset in crime predicts a lengthier and more frequent career [15, 20]. In line with this finding, adult-onset offenders were previously found to offend less frequently than those who had an early start in crime [2, 6]. For example, adult-onset offenders in the large-scale Queensland Longitudinal Dataset comprise 52% of the sample, but only are responsible for one out of four offenses [62]. In the CSDD, adult-onset offenders committed 2 crimes on average in their careers, while early-onset offenders on average committed 6 crimes in their careers [75]. Also, when comparisons are restricted to crimes committed in adulthood, juvenile-onset offenders still tend to commit more offenses than adult-onset offenders [48]. In most studies, it was found that the average career length decreases as onset age increases [38, 65, 75]. In contrast to these findings, Thornberry and Krohn [64] in their interactional theory predict that individuals starting their criminal career in late adolescence or emerging adulthood have more cognitive deficits and thus show more continuity in offending than individuals with an early crime onset.

Recidivism

In general, it was found that offenders with a late crime onset recidivate less often than offenders with an early crime onset. Of the late-onset offenders in the CSDD, 40% committed more than one crime compared to 80% of the early-onset offenders [72]. In the Queensland Longitudinal Dataset, most adult-onset offenders only offended once (57%) or twice (19%). Only 9% of the adult-onset offenders committed more than five offenses [62]. McGee and Farrington [38] found that the odds of becoming a recidivist were six times lower for adult- than for juvenile-onset offenders.

Crime Mix

The onset of some offenses takes place at earlier stages in life than other types [32]. For example, shoplifting, burglary, and vandalism tend to occur before adulthood, while robbery, drug trafficking, and rape are typically first committed in adulthood [26, 30]. This tendency also emerges when the crime mix of juvenile- and adult-onset offenders are compared. It was, for example, found that adult-onset offenders are relatively often involved in sex offenses, theft from work, vandalism, fraud, and carrying an offensive weapon. Compared to juvenile-onset offenders, they are less likely to be involved in robberies, burglaries, drug offenses, and (vehicle) thefts [38, 56].

Seriousness of Offending

In general, an early onset is found to be an indicator of a more serious criminal career [48]. Previous findings on the seriousness of adult-onset offending are scarce, and those studies that report on the seriousness of adult-onset offenders produce mixed findings. In some studies, it was found that crimes committed by adult-onset offenders on average are less severe than those committed by juvenile-onset offenders [2, 6]. For example, Thompson et al. [62] identified more than half of their large sample as adult-onset offenders, and 95% of these adult-onset offenders had brief offending careers and only committed minor offenses. One out of ten adult-onset offenders ever committed a serious offense; 43% of the adult-onset offenders only committed minor offenses [62]. Conversely, Wolfgang et al. [71] found that crimes committed by adult-onset offenders are significantly more serious than crimes committed by juvenile-onset offenders.

Offense Specialization

Overall, little specialization has been found over the life course [47]. Up to age 20, offenders become more and more versatile as they are committing more and more offenses [16]. From age 20 on, however, levels of specialization increase as offenders age and gain experience [39, 46]. Piquero et al. [46] studied specialization in early- and late-onset offender groups from the 1958 Philadelphia Birth Cohort and found that offenders with an early onset were more diverse than late-onset offenders. After controlling for age, this association was no longer significant, indicating that aging in itself attributes to increasing levels of specialization.

This Study

This study adds to the few recent studies that specifically focused on adult-onset offending in several ways. First, the studies on this specific offender group mostly focused on the correlates of adult-onset offending, trying to explain onset of offending in adulthood (e.g., [22, 73, 74]). The current study shows how dimensions of adult-onset criminal careers resemble or differ from those of juvenile-onset careers. Second, the limited number of studies that specifically focused on adult-onset offenders used rather small samples, from 93 to 385 individuals (e.g., [29, 58]).Footnote 3 This study uses a large recent sample (N = 43,338), which represents a proportionally stratified sample from a nationwide cohort of offenders and their criminal careers. Third, most of the studies only followed individuals up to their 20s [29, 62] or 30s [2, 11, 22, 58], missing out on individuals with an even later onset.Footnote 4 The current study follows individuals far into adulthood, up to 94 years of age. Fourth, the current study includes both men and women and is therefore able to compare juvenile- and adult-onset careers across gender.

The central aim of the study is to identify, describe, and compare criminal careers of men and women with a different onset age in terms of frequency, intensity, duration, recidivism, crime mix, seriousness, and specialization. For each measure of the criminal career, gender-specific comparisons are carried out between juvenile- and adult-onset offenders (respectively onset before and after age 18) and onset-specific comparisons are made between male and female offenders. This results in four comparisons:

-

(1)

juvenile-onset males vs. adult-onset males

-

(2)

juvenile-onset females vs. adult-onset females

-

(3)

juvenile-onset males vs. juvenile-onset females

-

(4)

adult-onset males vs. adult-onset females

Overall, it is expected that juvenile-onset offenders have more serious careers (highest frequency, highest intensity, highest recidivism rates, most serious crime, and most diverse crime mix) than adult-onset offenders and that men have more serious careers than women. Based on previous studies, it is expected that male juvenile-onset offenders have the most serious criminal careers and that female adult-onset offenders have the least serious criminal careers.

Data and Methods

Sample and Offending Careers

For this study, a representative sample of 50,000 from all 140,649 individuals (35.5%) who had a criminal record in the Netherlands in 2013 is used.Footnote 5 The sample is proportionally stratified by onset age and type of first offense in a way that the distributions of these two variables in the sample resemble the distributions in the population. The sample consists of 40,164 men (80.3%) and 9836 women (19.7%) committing a crime in 2013 in the Netherlands. Information on all judicial records from age 12 up to 1 July 2014 is derived from the Dutch Judicial Documentation System (JDS), which contains information on all judicial contacts that resulted in a conviction, acquittal, prosecutorial fine, or waiver.Footnote 6 Every record of a judicial contact contains information on the crime (e.g., date, type of crime), the individual committing the crime (e.g., gender, year of birth), and the way the crime was handled by the authorities (e.g., sentence). For the purpose of this study, traffic offenses were excluded. For the remaining 43,338 individuals (13% of the sample only committed traffic offenses), all criminal records from age 12 to his or her age at the end of the observation period or death are available.Footnote 7 We have information available on 988,152 age-years and together, the individuals are responsible for 241,915 criminal records. The data are mainly retrospective; individuals were selected because they had a judicial record in 2013; information is gathered on their criminal behavior from age 12 up to 1 July 2014. A small number of individuals died between their 2013 crime and the end of the observation period (N = 161, 0.4%). They are followed up to the date of their death. Because an offender cohort is used, individuals are followed up to different ages. Offenders were between 13 and 95 years of age at the end of the observation period (M = 34.8, sd = 14.3).

Measures

Official Age of Onset

Onset age is defined as the individual’s age at the first registration. The sample is divided into two groups based on the onset age of official offending. Juvenile-onset offenders are those with an onset before age 18; adult-onset offenders are those with an onset at or after age 18. Reasons for the use of 18 as cutoff age conform with Eggleston and Laub [11]. First, the age 18 defines the start of adulthood in most societies. Second, the age 18 is the legal age of majority in the Netherlands. Third, onset peaks around age 16; therefore, 18 truly is a late onset.

Frequency, Intensity, and Duration

Frequency of offending is the number of offenses committed in a particular period. Crime intensity refers to the average number of crimes per year in a particular period. Intensity is only examined for those individuals who had at least two records over their life course. Both frequency and intensity measures are given for the total career (all crimes and years included) and the adult career (only crimes and years included that were committed at or after age 18). Duration is defined as the number of years between the individual’s earliest registration and the individual’s last registration in the dataset, i.e., the age of desistance or termination. Individuals committing a single crime have a career duration equal to zero.

Recidivism

Recidivism identifies offenders by the number of crimes they commit. One-shot offenders are those who only commit a single crime. Recidivists are offenders who commit two or more crimes in their career. Chronics are offenders who commit ten or more crimes in their career (also including recidivists).

Crime Mix

Offense type is based on the standard classification of the Netherlands Bureau of Statistics. Crimes are classified into one of five types: violent offenses (including also sexual offenses and violent property offenses), property offenses, vandalism, drugs offenses, and other offenses.

Seriousness of Offending

Measuring seriousness is complex as definitions of crime seriousness vary widely [31]. In this study, two simple measures of seriousness are used. Firstly, crime seriousness is measured by the judicial settlement: was an unconditional prison sentence imposed and how long was this prison sentence? Since groups of offenders are compared, this measure results in proportions of offenders who received a prison sentence and means of the length of these prison sentences. A disadvantage of this measure is that judicial settlements are not only based on the seriousness of the crime but also depend on individual circumstances of the offender and the offender’s judicial history. Therefore, a second measure of seriousness, independent of other variables than the crime itself, is used. All crimes are categorized based on their statutory maximum punishment threat under the Dutch law into minor (0 to 4 years punishment threat), moderate (4 to 8 years punishment threat), or severe (8 years or more punishment threat).

Offense Specialization

As a measure of offense specialization, the diversity index is used. This individual measure of crime type versatility “reflects the probability that any two offenses drawn randomly from an individual’s particular set of offenses belong to separate offending categories” ([36], p. 1153). The diversity index is given by:

where p equals the proportion of offenses (i.e., the relative frequencies of each offense category) and m = 1, 2,…, M indicates the offense categories. The minimum value of D equals 0, indicating complete specialization. The maximum value of D when using five offense categories equals 0.8, indicating complete offense versatility.Footnote 8 One of the potential limitations of the diversity index is that the values of the index are confounded by offense frequency [60]. For this reason and next to an overall diversity index, juvenile- and adult-onset offenders with an equal number of total offenses are compared on their level of offense specialization.

Analyses

Because of the large sample sizes, tests for significant differences (t test for ratio variables and χ2 test for dichotomous and categorical variables) as well as effect sizes (Cohen’s d for ratio variables, odds ratio for dichotomous variables, and Cramer’s V for categorical variables) are used to indicate differences between the subgroups. Within each table and for each measure, a letter indicates whether the difference between two subgroups reaches significance with a conservative threshold of p < .001:

M for a significant difference between juvenile- and adult-onset males

F for a significant difference between juvenile- and adult-onset females

J for a significant difference between juvenile-onset males and juvenile-onset females

A for a significant difference between adult-onset males and adult-onset females. Clinical significance is indicated by these letters in bold. In such cases, the effect size d > .5 (for ratio variables), a significant odds ratio (for dichotomous variables), or Cramer’s V is significant (p < .05; for categorical variables).

Findings

Official Age of Onset

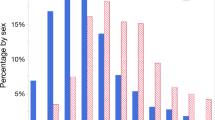

In the total sample, the average age of onset equals 25 years (Table 2). From all individuals, 39% had their first official record before their 18th birthday (juvenile-onset offenders) and 61% experienced a crime onset at age 18 or later (adult-onset offenders). If the first self-reported crime would have been 3 to 5 years earlier than the first official record, as was suggested in earlier studies [27, 30, 33, 42, 61], respectively, 42 to 36% of the sample would have an adult onset. Women are overrepresented among the adult-onset offenders (OR = 2.76, CI = 2.61–2.91). From all female offenders, 78% had an adult onset, compared to 57% from all male offenders. Male and female juvenile-onset offenders do not differ on their onset age (Table 3; both 15.5 years), but adult-onset females on average are a few years older when they start committing crimes than adult-onset males (34.1 vs. 30.0, t(10,775) = − 20.30, p < .001, d = − 0.30).

Adult-onset offenders by definition start offending later in life. An expected consequence of this and of the sampling procedure therefore is that adult-onset offenders are older on average at the end of the observation period than juvenile-onset offenders are. On average, male and female juvenile-onset offenders are followed-up to respectively 29 and 25 years of age. Both male and female adult-onset offenders are on average followed up to 39 years of age. Although information for both juvenile- and adult-onset offenders is available from age 12 on up to at least age 25, criminal careers of juvenile-onset offenders cover a limited number of years compared to those of adult-onset offenders. This should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings.Footnote 9

Frequency, Intensity, and Duration

Altogether, the adult-onset offenders are responsible for 94,720 crimes (39% of all crimes). Juvenile-onset offenders, although representing a smaller part of the sample, together commit 147,195 crimes (61% of all crimes). Both juvenile-onset males and females commit significantly more crimes than their adult-onset counterparts (Table 3; for men, 9.1 vs. 4.0, t(23,336) = 41.35, p < .001, d = 0.45; for women, 4.7 vs. 2.5, t(2277) = 10.69, p < .001, d = 0.31). Although the careers of male juvenile-onset offenders are on average 1.7 times longer than careers of male adult-onset offenders, male juvenile-onset offenders on average commit 2.3 as many crimes. When only taking into account crimes committed in adulthood, male juvenile-onset offenders on average commit 1.6 times more crimes than male adult-onset offenders (6.5 vs. 4.0, t(24,469) = 21.60, p < .001, d = 0.23), while female juvenile- and adult-onset offenders do not significantly differ on the number of crimes committing in adulthood (2.9 vs. 2.5, t(2327) = 2.30, p = .022, d = 0.05). The earlier the crime onset is, the more crimes are committed in the entire criminal career (Fig. 1). However, differences in the intensity of the criminal career between juvenile- and adult-onset offenders are small (for men, 1.0 vs. 0.9, t(19,793) = 12.26, p < .001, d = 0.11; for women, both 0.9, t(2899) = .005, p = .996, d = 0). Adult-onset offenders offend at a lower rate and therefore commit fewer crimes than juvenile-onset offenders. Both for men and women, career duration is longer for juvenile- than for adult-onset offenders (for men, 11.0 vs. 6.6 years, t(31,991) = 39.52, p < .001, d = 0.44; for women, 7.3 vs. 3.6, t(2553) = 16.03, p < .001, d = 0.45).

Recidivism

The odds of being a recidivist (two or more offenses) is 5.6 times higher for juvenile-onset males than for adult-onset males (Table 4; 87 vs. 54%, OR = 0.18, CI = 0.17–0.19) and 4.3 times higher for juvenile-onset females than for adult-onset females (72 vs. 38%, OR = 0.23, CI = 0.21–0.26). Also, adult-onset males recidivate more than adult-onset females (54 vs. 38%, OR = 0.52, CI = 0.49–0.55). Almost half of all male adult-onset offenders is a one-shot offender, while almost nine out of ten male juvenile-onset offenders recidivate. Chronics (ten or more offenses) are overrepresented among the juvenile-onset males (27%) compared to the adult-onset males (8%, OR = 0.24, CI = 0.23–0.26). Also, compared to adult-onset females, adult-onset males more often are chronics (OR = 0.36, CI = 0.31–0.42).

Figure 2 shows conditional probabilities differentiated by onset and gender. Conditional probabilities give the probability of committing crime k given that crime k − 1 is committed. The conditional probability for the third crime, for example, gives the probability of committing a third crime given that a second crime has been committed. Since we use an offender sample, all individuals commit at least one offense and therefore the conditional probability of the first crime equals 1. All groups show the same upward trend; the more crimes are committed, the higher probabilities are for a next crime. In other words, an offender who already committed ten crimes is more likely to commit an 11th crime than an offender who committed his second crime is to commit a third crime. As can be seen in Fig. 2, conditional probabilities are highest for male juvenile-onset offenders, while female adult-onset offenders have the lowest conditional probabilities. Once a juvenile man commits his first crime, he is very likely to continue his criminal career. An adult woman committing a first or second crime is less likely to commit a next crime. Conditional probabilities for the tenth offense and next offenses converge for the different groups; once an offender commits about ten crimes, he or she is likely to pursue committing crimes, irrespective of gender and onset age.

Crime Mix

A comparison of the first crime and total career in terms of crime mix between the four offender groups is shown in Table 4. The type of the first crime is different for males with a juvenile and adult onset (χ2 = 2553.88, df = 4, p < .001; Cramer’s V = 0.27, p < .001). While juvenile-onset males more often start a criminal career with a property crime (adjusted residual = 30.5) or vandalism (adjusted residual = 14.7), adult-onset males more often commit drug-related crimes (adjusted residual = − 22.0) or violence (adjusted residual = − 2.0). Women with a juvenile and adult onset also differ on their first crime (χ2 = 672.76, df = 4, p < .001; Cramer’s V = 0.28, p < .001); juveniles more often start by committing vandalism (adjusted residual = 17.3) or violence (adjusted residual = 12.0), while adults tend to start committing a drug-related crime (adjusted residual = − 9.2) or property crime (adjusted residual = − 2.3). Adult-onset offenders of a different gender also differ on their first crime (χ2 = 1164.87, df = 4, p < .001; Cramer’s V = 0.21, p < .001); men are more likely to commit vandalism (adjusted residual = 20.8) or violence (adjusted residual = 16.5), while women more often start their criminal career by committing a property crime (adjusted residual = − 29.2) or drug-related crime (adjusted residual = − 1.6).

Next to the type of the first offense, it can be questioned to what extent the types of crimes committed later on in the lives of juvenile- and adult-onset offenders differ. On average in their total career, male juvenile-onset offenders commit more crimes than male adult-onset offenders of every offense; they commit more violent crimes (1.9 vs. 0.8, t(23,794) = 44.71, p < .001, d = 0.51), more property crimes (4.6 vs. 1.6, t(23,039) = 30.53, p < .001, d = 0.34), more vandalism (1.5 vs. 0.6, t(25,431) = 44.63, p < .001, d = 0.52), more drug-related crimes (0.4 vs. 0.2, t(26,276) = 16.89, p < .001, d = 0.23), and more other types of crime (0.8 vs. 0.7, t(34,721) = 7.36, p < .001, d = 0.08). Male adult-onset offenders, however, commit more crimes of each type than female adult-onset offenders do.

Seriousness of Offending

Offenders of the same gender but with a different onset (juvenile vs. adult) do not significantly differ on the probability of a prison sentence after the first offense (Table 5). Adult-onset offenders, however, who are imprisoned, receive longer prison sentences than juvenile-onset offenders of the same gender (men, 0.8 vs. 0.2 years, t(827) = −9.04, p < .001, d = 0.49; women, 0.8 vs. 0.2 years, t(92) = −4.11, p < .001, d = −0.60). First crimes of adult-onset offenders more often are minor (men, 33%; women, 31%), while juvenile-onset offenders more often commit moderate (men, 78%; women, 84%) and serious crimes (men, 9%; women, 4%). More than half of the juvenile-onset males received a prison sentence at some point in their careers compared to 29% of the adult-onset males (OR = 0.32, CI = 0.30–0.33). Juvenile-onset compared to adult-onset females also twice as often are imprisoned at some points in their lives (26 vs. 12%, OR = 0.39, CI = 0.34–0.45).

On average, juvenile-onset males more often received prison sentences than adult-onset males (2.7 vs. 0.9, t(22,158) = 37.22, p < .001, d = 0.42) and also spent more time in prison in total (1.7 vs. 1.4 years, t(7563) = 5.90, p < .001, d = 0.12). Compared to adult-onset females, adult-onset males more often received prison sentences (0.9 vs. 0.4, t(17,049) = 17.59, p < .001, d = 0.20) and spent more time in prison (1.4 vs. 0.7, t(685) = 8.89, p < 001, d = 0.37). More juvenile- than adult-onset males ever committed a minor crime (58 vs. 52%, OR = 0.78, CI = 0.75–0.81). More juvenile- than adult-onset males ever committed a moderate crime (93 vs. 76%; OR = 0.23, CI = 0.21–0.25) and ever committed a serious crime (38 vs. 13%; OR = 0.25, CI = 0.24–0.26). Like men, juvenile- and adult-onset females show about the same difference regarding moderate and serious crimes. However, adult-onset females as often as juvenile-onset females commit at least one minor crime (40 vs. 37%, χ2 = 4.37, df = 1, p = .037).

Some types of crime are more serious in nature than other types. Therefore, offense seriousness is also distinguished by offense type for all offender groups (Table 6). Within most types of crime and both for men and women, offenses committed by juvenile-onset offenders more often are serious and less often are minor. Only for some offenses, where the level of seriousness is mostly low (other) or moderate (property), numbers are equal for juvenile- and adult-onset offenders. An exception is female adult-onset offenders, who commit more serious vandalism than female juvenile-onset offenders do.

Offense Specialization

Only recidivists (those who commit more than one crime) can be diverse or specialized in their offending. Therefore, one-shot offenders are excluded from the analyses on specialization. Overall, juvenile-onset offenders show higher levels of diversity in their offending than adult-onset offenders (Table 7; men, 0.51 vs. 0.43, t(20,859) = 28.41, p < .001, d = 0.37; women, 0.40 vs. 0.28, t(2876) = 14.97, p < .001, d = 0.50) and men show higher levels of diversity than women (juvenile onset, 0.51 vs. 0.40, t(1509) = 15.77, p < .001, d = 0.51; adult onset, 0.43 vs. 0.28, t(3529) = 26.34, p < .001, d = 0.62). Because the diversity index is confounded by offense frequency, individuals with an equal number of offenses are also compared on their level of offense specialization. These comparisons confirm that, regardless of the frequency of offending, adult-onset offenders show higher levels of offense specialization than juvenile-onset offenders and women show higher levels of offense specialization than men. However, the effect sizes indicate a small to large difference between both offender groups (d = 0.09–1.05).

Conclusions and Discussion

The central aim of this study was to explore the criminal careers of those with a delayed onset of offending. Using a sample of 43,338 offenders with criminal careers spanning from age 12 to a maximum of age 96, the underexplored group of offenders with a delayed onset was compared to those with a juvenile crime onset. Almost two out of three offenders in this study experienced an official onset in adulthood. This proportion is among the higher ones found in offender samples in other studies. Juvenile-onset offenders, however, together commit more crimes than adult-onset offenders; they are responsible for two out of three crimes. While earlier studies showed mixed results in relation to gender and adult-onset offending [4, 6, 62], the current study clearly showed that female offenders are overrepresented among the adult-onset offenders; the odds of being an adult-onset offender is almost three times higher for female offenders than for male offenders.

This study showed that features of criminal careers of adult-onset offenders are significantly different from those of juvenile-onset offenders. The key finding that emerged from the comparison is that criminal careers of both male and female adult-and juvenile-onset offenders do not only differ in the timing of onset, but also in terms of frequency, duration, recidivism, crime mix, seriousness, and specialization. Overall, the same differences between juvenile- adult-onset offenders are found in males and females, except for the prevalence and intensity of offending; juvenile-onset males show a higher intensity of offending than adult-onset males, but no differences in crime intensity were found between juvenile- and adult-onset females. Criminal careers of both male and female juvenile-onset offenders are more serious than those of their adult-onset counterparts; they commit approximately two times more crimes on average, three times more often are chronics, approximately two times more often receive prison sentences and spend almost three times as long in prison in their total careers. Furthermore, the crime mix of juvenile-onset offenders is more diverse; adult-onset offenders show higher levels of crime type specialization. In general, juvenile-onset offenders have more serious criminal careers than adult-onset offenders and men have more serious criminal careers than women. Male juvenile-onset offenders have the highest scores of all groups on most criminal career dimensions; they have the longest careers, commit the most crimes, commit most serious crimes, are imposed the most and longest prison sentences in their careers, most often recidivate, are most often chronics, and have the most diverse crime mix. Female adult-onset offenders, both compared to female juvenile-onset and male adult-onset offenders, have the shortest careers, commit the least crimes, are least likely to recidivate or become a chronic, receive the least prison sentences and spend the shortest time in prison in their career, and have the highest levels of offense specialization.

Most findings from this study are in line with general assumptions on criminal careers; career length decreases as onset age increases [65], recidivism rates decrease when onset age increases [72], an early onset is an indicator of a more serious criminal career [48], and crime type specialization is higher for older offenders [39]. In contrast to earlier findings [38], both male and female adult-onset offenders were found to relatively often start their career with a drug-related crime. Another remarkable finding is that juvenile-onset offenders, both men and women, are more often sentenced to prison following their first crime, but adult-onset offenders are imposed four times longer prison sentences following the first crime than juvenile-onset offenders. A possible explanation for this difference is that adult offenders are considered more responsible for their actions than juveniles.

Several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the current study relies on official data, not including self-reported crime. The relatively high proportion of adult-onset offenders may reflect the fact that not all crimes are detected and solved. However, as argued before, the availability of self-reported offending does not per se lower the proportion of adult-onset offending since official non-offenders also tend to self-report offending that started in adulthood (e.g., [29, 73, 74]). It should be noticed that large proportions of adult-onset offending do not contradict previous findings per se that the onset of offending peaks at age 14 [14]. A juvenile crime onset ranges from the moment individuals can be regarded delinquent to age 17, a period spanning around 10 years. An adult onset can take place not only at age 18, but also at age 70 or even age 90 and any moment in between. Secondly, related to the previous argument, selection bias may have a different effect on different onset and gender groups and therefore may influence the findings of this study. For example, earlier studies show that older offenders and men are less likely to get arrested than younger offenders and women are [7, 9]. Therefore, real differences can be smaller than what is found in the comparisons. Offenses committed by older and female offenders are possibly underestimated since these are less likely to be detected by the authorities. Thirdly, the downside of the large sample of offenders from a crime year cohort is that offenders were born at different moments in time. This raises potential for different patterns of prevalence of different probabilities of apprehension for different offenders. However, as long as such cohort effects apply equally to men and women and juvenile- and adult-onset offenders, these effects can be ruled out and do not influence the group comparisons made in this study. Fourthly, while the data used in this study are rich regarding criminal detail (date and type of offense, sentencing information), it lacks personal information on the offenders except for dates of birth and gender. Therefore, we were not able to analyze criminal development in relation to development on other life domains, such as employment, housing, and parenthood. Differences on such developments between both groups could help explain differences in their offense patterns. For example, if adult-onset offenders are more likely to have children than juvenile-onset offenders, this may affect their offense patterns.

While the theoretical and practical relevance of studying the criminal development of young offenders is widely acknowledged, much less is known about the group of offenders who only start offending later on in life. From a theoretical perspective and in accordance with previous studies [6, 11, 22, 29, 38, 45, 62, 75], the findings of this study contribute to existing knowledge in that it shows that both male and female adult-onset offenders constitute a significant proportion of all offenders and therefore challenges propensity theories of offending which argue that crime onset after adolescence is extremely rare [42, 51]. The findings of this study are more in line with dynamical theories, allowing differences between offenders and changes within individuals over time. This study shows that the timing of onset is related to the offense pattern that follows onset; adult-onset offenders follow different crime patterns than juvenile-onset offenders. In line with these findings, it can be expected that explanations for the criminal behavior of adult-onset offenders may also be different. These empirical results, therefore, challenge the claim that a tailored theory for adult-onset offenders is a pointless exercise [2].

Knowledge on criminal career dimensions of adult-onset offenders can further practical understanding of whether adult-onset offenders should be handled in the same way juvenile-onset offenders are handled, in terms of prevention strategies and sentencing. Firstly, prevention strategies should shift part of their focus to older offenders. It was often argued that the best predictor of (criminal) behavior is previous (criminal) behavior, and adult offenders are thought to have a long history of delinquent behavior. Therefore, intervention strategies are mainly aimed at early prevention of juveniles (for a review, see e.g., [67]) and are regarded the most cost effective [24]. The substantial amount of adult-onset offenders found in this study suggests that early prevention strategies should be complemented by a focus on those with a late onset, especially to reduce the total number of offenders.

Secondly, once they have started their criminal career, further prevention should take into account the differences in developmental patterns of those with a different onset age, especially for women where adult-onset offending is even more prevalent than in men. For example, recidivism rates are significantly different for juvenile- and adult-onset offenders. Once an adult-onset offender has committed about ten offenses, however, the probability that he or she recidivates is almost equal to the probability that a juvenile-onset offender recidivates after the tenth offense. Based on the current study, it can, therefore, be argued that a combination of the onset age and the number of previous crimes of an offender should be taken into account when recidivism risks of known offenders are estimated. Another dimension that calls for adjusting prevention and investigation strategies to the type of offender is the specialization of offending. While little specialization in offending is generally found [47], this study shows that differentiation between offenders leads to different offense patterns in terms of specialization. Prevention and investigation strategies may, therefore, be differentiated based on the age at which individuals are first caught. In sum, the findings of this study are a call for a new focus of prevention and intervention strategies, for male, but even more important, for female offenders.

Beyond the scope of this study, an imperative next step would be to explain a delayed crime onset. Understanding of mechanisms underlying crime onset at different ages is crucial to understanding the causes of criminal behavior. Past studies that aimed at explaining adult-onset offending mostly used stable variables measured in adolescence to explain adult behavior. Future research should also incorporate time-varying variables available far into adulthood, such as longitudinal information on marriage, employment, childbirth, life success, and major life events. By doing so, such studies would be able to unravel the mechanisms and circumstances under which an adult onset emerges and adult criminal careers develop.

Notes

It should be noted that definitions of crime can highly influence the assumptions embedded in a theory. For example, Robins’ [51] definition of childhood antisocial behavior is much broader than the legal definition of delinquent or criminal behavior, for example, including fighting and dropping out of school.

One exception is the study by Thompson et al. [62]. They, however, only follow individuals up to age 25.

Because of budgetary reasons, a sample instead of the population was used for this study.

Cases that ended in an acquittal were excluded from the analyses. For more information on the Dutch Judicial Documentation System (JDS), see Wartna et al. [66].

The first record in the dataset is in 1942. In 2013, the mean age of offenders in the sample equals to 33.3 years (sd = 14.3). The youngest offenders were 12, while the oldest offender was 95 in 2013.

The maximum value of D depends on the number of offense categories used and is given by Dmax = (k − 1) / k, where k gives the number of offense categories.

Furthermore, it should be noted that these descriptives are not controlled for by periods of incarceration. However, as can be seen from Table 5, juvenile-onset offenders received three times as many prison sentences and spent more time in prison during their total career than adult-onset offenders. Therefore, differences between frequency, career duration, and intensity would only become larger when periods of incarceration would be taken into account.

References

Andersson, F., & Torstensson Levander, M. (2013). Adult onset offending in a Swedish female birth cohort. Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 172–177.

Beckley, A. L., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Houts, R. M., McGee, T. R., Morgan, N., Schroeder, F., Ramrakha, S., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2016). Adult-onset offenders: is a tailored theory warranted? Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 64–81.

Block, C. R., Blokland, A. A. J., van der Werff, C., van Os, R., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2010). Long-term patterns of offending in women. Feminist Criminology, 5(1), 73–107.

Blokland, A. A. J., & Palmen, H. (2012). Criminal career patterns. In R. Loeber, M. Hoeve, N. W. Slot, & P. van der Laan (Eds.), Persisters and Desisters in crime from adolescence into adulthood: explanation, prevention and punishment (pp. 13–50). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J. A., & Visher, C. A. (1986). Criminal careers and career criminals. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Carrington, P. J., Matarazzo, A., & DeSouza, P. (2005). Court careers of a Canadian birth cohort. Crime and justice research paper series, no. 6. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

Charette, Y., & van Koppen, M. V. (2015). A capture-recapture model to estimate the effects of extra-legal disparities on crime funnel selectivity and punishment avoidance. Security Journal. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2015.30.

DeLisi, M., & Piquero, A. R. (2011). New frontiers in criminal career research, 2000–2011: a state-of-the-art-review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39, 289–301.

Doerner, J. K., & Demuth, S. (2010). The independent and joint effects of race/ethnicity, gender, and age on sentencing outcomes in U.S. federal courts. Justice Quarterly, 27, 1–27.

Donnellan, M. B., Ge, X., & Wenk, E. (2002). Personality characteristics of juvenile offenders: differences in the CPI by age at first arrest and frequency of offending. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 727–740.

Eggleston, E. P., & Laub, J. H. (2002). The onset of adult offending: a neglected dimension of the criminal career. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30, 603–622.

Elander, J., Rutter, M., Simonoff, E., & Pickles, A. (2000). Explanations for apparent late onset criminality in a high-risk sample of children followed up in adult life. British Journal of Criminology, 40, 497–509.

Farrington, D. P. (1983). Offending from 10 to 25 years of age. In K. T. van Dusen & S. A. Mednick (Eds.), Prospective studies of crime and delinquency (pp. 17–37). Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff.

Farrington, D. P. (1986). Age and crime. Crime and Justice, 7, 189–250.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). Developmental and life-course criminology: key theoretical and empirical issues—the 2002 Sutherland Award address. Criminology, 41, 221–255.

Farrington, D. P. (2014). Integrated cognitive antisocial potential theory. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 2552–2564). New York: Springer.

Farrington, D. P., & Maughan, B. (1999). Criminal careers of two London cohorts. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 9, 91–106.

Farrington, D. P., Loeber, R., Elliott, D. S., Hawkins, J. D., Kandel, D. B., Klein, M. W., McCord, J., Rowe, D. C., & Tremblay, R. E. (1990). Advancing knowledge about the onset of delinquency and crime. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology, vol. 13 (pp. 283–342). New York: Plenum.

Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., & Coid, J. W. (2009). Development of adolescence-limited, late-onset and persistent offenders from age 8 to age 48. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 150–163.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age: recent results from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. New York: Springer.

Glueck, S., & Glueck, E. (1968). Delinquents and nondelinquents in perspective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gomez-Smith, Z., & Piquero, A. R. (2005). An examination of adult onset offending. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33, 515–525.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (2016). The criminal career perspective as an explanation of crime and a guide to crime control policy: the view from general theories of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53, 406–419.

Harris, P. M. (2011). The first-time adult-onset offender: findings from a community corrections cohort. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55, 949–981.

Harris, D. A. (2012). Age and type of onset of offending: results from a sample of male sexual offenders referred for civil commitment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57, 1226–1247.

Kazemian, L., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Comparing the validity of prospective, retrospective, and official onset for different offending categories. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 21, 127–147.

Kratzer, L., & Hodgins, S. (1999). A typology of offenders: a test of Moffitt’s theory among males and females from childhood to age 30. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 9, 57–73.

Lay, B., Ihle, W., Esser, G., & Schmidt, M. H. (2005). Juvenile-episodic, continued or adult-onset delinquency? Risk conditions analysed in a cohort of children followed up to the age of 25 years. European Journal of Criminology, 2, 39–66.

Le Blanc, M., & Fréchette, M. (1989). Male criminal activity from childhood through youth. New York: Springer.

Liu, J., Francis, B., & Soothill, K. (2011). A longitudinal study of escalation in crime seriousness. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 27, 175–196.

Loeber, R. (1988). Natural histories of conduct problems, delinquency, and associated substance use: evidence for developmental progressions. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology, vol 11 (pp. 73–124). New York: Plenum.

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., & Petechuk, D. (2003). Child delinquency: early intervention and prevention. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Magnusson, D. (1988). Individual development from an interactional perspective: a longitudinal study. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mata, A. D., & van Dulmen, M. H. M. (2012). Adult-onset antisocial behavior trajectories: associations with adolescent family processes and emerging adulthood functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 177–193.

Mazerolle, P., Brame, R., Paternoster, R., Piquero, A., & Dean, C. (2000). Onset age, persistence, and offending versatility: comparisons across gender. Criminology, 38, 1143–1172.

McCord, J. (1978). A thirty-year follow-up of treatment effects. American Psychologist, 33, 284–289.

McGee, T. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). Are there any true adult-onset offenders? British Journal of Criminology, 50, 530–549.

McGloin, J. M., Sullivan, C. J., Piquero, A. R., & Pratt, T. C. (2007). Local life circumstances and offending specialization/versatility: comparing opportunity and propensity models. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 44, 321–346.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E. (2006). A review of research on the taxonomy of life-course persistent and adolescence-limited offending. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & M. Coleman (Eds.), Taking stock: the status of criminological theory. Advances in criminological theory, vol. 15 (pp. 277–311). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Rutter, M., & Silva, P. A. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D. S. (2016). Group-based trajectory modeling and criminal career research. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53(3), 356–371.

Nilsson, A., Bäckman, O., & Estrada, F. (2013). Involvement in crime, individual resources and structural contraints: process of cumulative (dis)advantage in a Stockholm birth cohort. British Journal of Criminology, 53, 297–318.

Piquero, A. R., Paternoster, R., Mazerolle, P., Brame, R., & Dean, C. W. (1999). Onset age and offense specialization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36, 275–299.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2003). The criminal career paradigm. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice a review of research (pp. 359–506). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: new analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pulkkinen, L., Lyyra, A. L., & Kokko, K. (2009). Life success of males on nonoffender, adolescence-limited, persistent, and adult-onset antisocial pathways: follow-up from age 8 to 42. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 117–135.

Robins, L. N. (1966). Deviant children growing up: a sociological and psychiatric study of sociopathic personality. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company.

Robins, L. N. (1978). Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behaviour: replications from longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 8, 611–622.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1990). Crime and deviance over the life course: the salience of adult social bonds. American Sociological Review, 55, 609–627.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2003). Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Criminology, 41, 555–592.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2005). A general age-graded theory of crime: lessons learned and the future of life-course criminology. In D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 165–181). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Sapouna, M. (2015). Adult-onset offending: a neglected reality? Findings from a contemporary British general population cohort. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15622429.

Shannon, L. W. (1988). Criminal career continuity: its social context. New York: Human Sciences Press.

Sohoni, T., Paternoster, R., McGloin, J. M., & Bachman, R. (2014). Hen’s teeth and horse’s toes: the adult onset offender in criminology. Journal of Crime and Justice, 37, 155–172.

Stattin, H., Magnusson, D., & Reichel, H. (1989). Criminal activity at different ages: a study based on a Swedish longitudinal research population. British Journal of Criminology, 29, 368–385.

Sullivan, C. J., McGloin, J. M., Ray, J. V., & Caudy, M. S. (2009). Detecting specialization in offending: comparing analytic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 419–441.

Theobald, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2014). Onset of offending. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 3332–3342). New York: Springer.

Thompson, C. M., Stewart, A. L., Allard, T. J., Chrzanowski, A., Luker, C., & Sveticic J.. (2014). Understanding the extent and nature of adult-onset offending: implications for the effective and efficient use of criminal justice and crime reduction sources. Report to the Criminology Research Advisory Council.

Thornberry, T. P. (2005). Explaining multiple patterns of offending across the life course and across generations. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602, 156–195.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2005). Applying interactional theory to the explanation of continuity and change in antisocial behavior. In D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 183–209). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Tracy, P. E., & Kempf-Leonard, K. (1996). Continuity and discontinuity in criminal careers. New York: Plenum Press.

Wartna, B. S. J., Blom, M., & Tollenaar, N. (2011). The Dutch recidivism monitor. The Hague: WODC.

Welsh, B. C., Farrington, D. P., & Raffan Gowar, B. (2015). Benefit-cost analysis of crime prevention programs. Crime and Justice. A Review of Research, 44, 447–516.

Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (1992). Overcoming the odds: high risk children from birth to adulthood. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

White, N. A., & Piquero, A. R. (2004). A preliminary empirical test of Silverthorn and Frick’s delayed-onset pathway in girls using an urban, African-American, US-based sample. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 14, 291–309.

Wiecko, F. M. (2012). Late-onset offending: fact or fiction. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X12458503.

Wolfgang, M. E., Thornberry, T. P., & Figlio, R. M. (1987). From boy to man, from delinquency to crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zara, G. (2012). Adult onset offending: perspectives for future research. In R. Loeber & B. C. Welsh (Eds.), The future of criminology (pp. 85–93). New York: Oxford University Press.

Zara, G., & Farrington, D. P. (2009). Childhood and adolescent predictors of late onset criminal careers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 287–300.

Zara, G., & Farrington, D. P. (2010). A longitudinal analysis of early risk factors for adult-onset offending: what predicts a delayed criminal career? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20, 257–273.

Zara, G., & Farrington, D. P. (2013). Assessment of risk for juvenile compared with adult criminal onset: implications for policy, prevention, and intervention. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19, 235–249.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a VENI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant number 451-14-008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Koppen, M.V. Criminal Career Dimensions of Juvenile- and Adult-Onset Offenders. J Dev Life Course Criminology 4, 92–119 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0074-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0074-5