Abstract

Introduction

To determine the disease burden and costs in moderate-to-severe chronic osteoarthritis (OA) pain refractory to standard-of-care treatment in the Spanish National Health System (NHS).

Methods

Ancillary analysis of the OPIOIDS real-world, non-interventional, retrospective, 4-year longitudinal study including patients aged at least 18 years with moderate-to-severe chronic OA pain refractory to standard-of-care with sequential NSAIDs plus opioids. Burden assessment included measurement of analgesia, cognitive functioning, basic activities of daily living, severity and frequency of comorbidities, and all-cause mortality. Costs accounted for healthcare resource utilization and related costs (year 2018).

Results

Records of 13,317 patients were analyzed; 68.9 (14.7) years old, 71.3% (70.5–72.1%) women, 58.1% refractory to NSAID plus weak opioid and 41.9% to NSAID plus strong opioid, accounting for 10.7% (10.5–10.8%) of patients with chronic OA pain. Mean number of comorbidities was 2.9 (1.8) and its severity was 1.8 (1.7). Pain decreased by 0.9 points (12.2%) and cognitive declined by 2.3 points (9.1%, with 4.3% more patients with cognitive deficit) and dependency worsened by 0.4 points (0.5%, with 2.3% more patients with severe-to-total dependence) over a mean treatment period of 188.6 (185.4–191.8) days on NSAIDs followed by 400.6 (393.7–407.5) days on opioids. The adjusted mortality rate was higher in patients with OA taking NSAID plus strong opioids; hazard ratio 1.44 (1.26–1.65; p < 0.001). The 4-year healthcare cost was €7350/patient (€7193–7507 or €1838/year) and was higher in those taking strong versus weak opioids; €9886 (€9608–10,164, €2472/year) vs. €5519 (€5349–5689, €1380/year), p < 0.001. Analgesia cost (16.0% of total cost, 70.2% opioids) was higher with strong versus weak opioids, 19.6% vs. 11.3%, p < 0.001.

Conclusions

In routine clinical practice in Spain, patients with moderate-to-severe chronic OA pain refractory to standard analgesic treatment with NSAIDs plus opioids reported modest reductions in pain, while presenting a considerable burden of comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and dependency. Healthcare costs significantly increased for the NHS particularly with NSAIDs plus strong opioids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint pathology; it has an incidence of 6–24% (patients with chronic OA pain of more than 3 months’ duration) and it is associated with more than one chronic condition |

Refractory pain may persist in patients with OA who are non-responders to first-choice painkillers after combined or sequential treatment with NSAIDs and opioids. Despite its controversy, opioid use has increased in recent decades in Spain, having an impact on society and the related costs of the non-healthcare and healthcare systems |

In this study, we determined the burden and cost of disease in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic OA pain who are refractory to standard analgesic treatment from the perspective of the NHS in Spain |

What was learned from the study? |

In routine clinical practice in Spain, patients with moderate-to-severe OA chronic pain refractory to standard analgesic treatment with NSAIDs plus opioids reported modest reduction in pain, while presenting a considerable burden of comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and level of dependency in a relatively short period of treatment |

Consequently, healthcare costs per patient significantly increased for the NHS, particularly when considering treatments with strong opioids; €2472/year vs. €1380/year with weak opioids |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13348007.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint pathology with prevalence varying depending on the affected joint and the criteria used to define the disease [1, 2]. Between 6% and 24% of adults have OA with chronic pain of more than 3 months’ duration, with incidence increasing with aging [3,4,5]. In Spain, the study on prevalence of rheumatic diseases (EPISER) showed a prevalence of OA in any joint of 29.4% in persons aged over 40 years [5]. In addition to nociceptive pain, OA is accompanied by increased disability for the activities of daily living, which has a negative effect on health-related quality of life and is one of the main causes of absenteeism (days off from work due to sick leave), resulting in high health and non-healthcare costs for health systems and society [2, 5, 6]. Most people with OA have at least one chronic condition, especially cardiometabolic conditions, but also osteoporosis, depression, and other comorbidities [7,8,9]. Therefore, given its high prevalence and impact on the health budget, it should be considered a serious public health problem of considerable magnitude [4, 10].

The goal of treatment is to control symptoms and reduce disease progression [11]. Treatment requires the combination of non-pharmacological (education, exercise, weight loss, etc.) and, when needed, pharmacological therapy (acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], metamizole, symptomatic slow-acting drug in osteoarthritis [SYSADOA], short-term opioids utilization, etc.) [1, 11, 12]. Drug-based treatment should be customized for each patient, considering the benefit–risk balance of therapies and assuming that a safe and efficacious approach is not available at present [12,13,14]. NSAIDs, particularly topical forms, may be used in patients who do not respond to first-choice painkillers such as acetaminophen, which is expected to have little clinical benefit on patient’s pain [14, 15]. Weak and strong opioids are used by primary care physicians and specialist both in moderate-to-severe pain with insufficient response to other treatments based on non-narcotic analgesics and/or NSAIDs, although adverse effects are common and may force treatment abandonment, and effectiveness of pain reduction is modest in magnitude [13, 16, 17]. In fact, opioid use is not without controversy, and some scientific societies such as Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) or the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) do not recommend them [18, 19]. However, refractory pain (pain that cannot be adequately controlled despite non-pharmacological measurements and pharmacological drugs) persists in a percentage of patients after using combinations or sequential treatment with NSAIDs and opioids [20, 21]. As in comparable countries, in Spain opioid use has increased in recent decades [22], although their efficacy in reducing pain is modest and they are accompanied by increased cognitive decline and dependence for activities of daily living, which results in an increase in the burden and cost of the disease for the Spanish National Health System (NHS) [23].

The objective of this study was to estimate the burden and cost of the disease in patients with chronic OA pain in any joint refractory to usual treatment based on drug analgesia with an NSAID followed by a sequential or concomitant opioid, in addition to usual non-pharmacological measures. The analysis was carried out under real-world conditions of usual medical practice from the perspective of the Spanish NHS.

Methods

Design, Site, and Data Source

Secondary analysis of a non-interventional, multicenter, longitudinal, retrospective study using electronic medical records (EMR): the Outcomes in Patients usIng Opioids In Painful Disorders in Spain (OPIOIDS) study, whose design, methods, and main findings are available elsewhere [23]. The study population was obtained from the health records of health providers unified in the BIG-PAC anonymized database, registered with the European Network of Centers for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP®) which is coordinated by the European Medicines Agency (http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=29236). Data came from computerized medical records and complementary databases of financing/provision of public services of seven Spanish Autonomous Communities, with an assigned population of approximately 1.81 million (81.2% [95% confidence interval 81.1–81.3%] adults aged at least 18 years). The patient data included in the database are de-identified as specified in Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, On the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights. Permission to abstract data was obtained by database owner.

Study Population (Cohort)

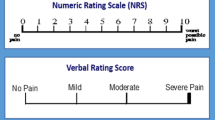

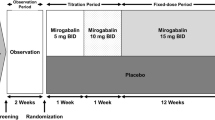

The patient cohort analyzed includes EMR of patients with a diagnosis of chronic OA pain as defined in the following section who were unresponsive to an analgesic therapy consisting of a combination of an NSAID plus an opioid. Unresponsive was considered if the pain, after receiving such combination at the recommended posology and dose, still scored 5 or more on a pain numeric rating scale of 11 points (0 no pain, 10 worst possible pain) [24], which was the criterion of refractoriness considered in the analysis. NSAID plus an opioid could be taken sequentially or added concomitantly. Before opioid initiation, the EMR evaluated must belong to active patients (with at least two health records) in the database in a minimum of 12 months before the index date showing that they had received at least two prescriptions of an NSAID with any active substance, alone or combined with another usual non-narcotic analgesic such as metamizole or acetaminophen. Patients could have taken another common analgesic, such as acetaminophen or metamizole concomitantly, in addition to educational measures, lifestyle changes, dietary measures, and physiotherapy according to the recommendations on OA treatment in Spain [25]. Discontinuation was defined as more than 30 days without renewing the last opioid prescription in those patients who have been dispensed at least two prescriptions of the same opioid in the community pharmacy during the study period. Refractory patients could discontinue the study by switching to an analgesic other than those previously used, by switching to a strong opioid if a weak opioid was used as the inclusion criterion, referral to the pain unit or surgery for invasive treatments, loss to follow-up, and/or death from any cause. EMR of patients not tolerating NSAID or opioid drugs were not included in this analysis. The recruitment period for the initiation of the opioid drug was January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015 (index date), and patients were followed from the index date up to a maximum of 3 years and/or until treatment discontinuation (follow-up period), as defined below.

The inclusion criteria were (a) age at least 18 years, (b) diagnosis of OA with chronic nociceptive pain of more than 3 months’ duration with International Classification of Diseases (10th edition) Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes as defined below, (c) active patients (at least two health records) in the database a minimum of 12 months before index date, (d) inclusion in the chronic prescription program (with a proven record of the daily dose, the time interval, and duration of each treatment administered (at least two prescriptions during the follow-up period), and (e) guaranteed regular follow-up of patients (at least two health records in the computer system) from the index date onwards. Exclusion criteria were (a) subjects transferred to other centers, displaced, or out of area; (b) permanently institutionalized patients; (c) terminal disease and/or on dialysis (ICD-10 code N18); or (d) with neuropathic pain/radiculopathy (ICD-10 code G50–65) or associated cancer (ICD-10 code G89.6). The EMR of patients who abandoned any of the treatments that defined participation in this study as a result of problems of tolerability (more than 30 days without renewing the initial medication dispensed in the community pharmacy and without refills during the study follow-up) and those who did not have a prescription fulfilled by a pharmacy after a prescription by the physician (primary failure of therapeutic adherence) were discarded.

Definition of Diagnosis

Records of patients with OA were obtained using the ICD-10-CM. Chronic pain was defined as pain that persisted for more than 3 months [20, 21] and refractory pain as previously defined. The joints of pain were (a) hip and knee (M16, M17), (b) spine (M54.5), and other joints (M15, M18, M19, M40, M41).

Treatment Description, Adherence, and Persistence

The drugs indicated for the treatment of chronic OA pain were obtained according to the Anatomical Chemical Therapeutic Classification System (ATC, N02AA01 to N02AX06). The information was obtained from the records of drug prescriptions. The choice of drug in a specific patient was at the discretion of the physician (clinical practice). The medical specialty that initiated the prescription was determined. We included (a) non-opioid analgesics (NSAIDs, acetaminophen, metamizole), (b) weak opioids (codeine, dihydrocodeine, tramadol, tramadol in combination, dextropropoxyphene), and (c) strong opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone plus naloxone, oxycodone, pethidine, tapentadol). The study records were obtained during the 12 months before and 36 months after index date (total 4 years). The index date was the start of a new weak or strong opioid treatment from the date of diagnosis of chronic nociceptive pain due to OA.

Adherence was defined as the percentage of patients who, at 12, 24, and 36 months after the index date, remained in the study on the initial opioid that led to study inclusion [26]. The medication possession ratio (MPR) was measured as the ratio between the number of days on the medication dispensed and the days of follow-up (time in treatment) in the study, expressed as a percentage. Persistence was defined as the days of follow-up in the study and was calculated as the difference between the start date of the medication (day of prescribing of the NSAID which was followed by an opioid) and the date of the patient’s completion of the study [26]. Persistence was counted for NSAIDs and opioids. The completion date was that which occurred first during the 3 years of follow-up after adding an opioid: (a) adherence to the opioid initially prescribed after an NSAID, (b) discontinuation for a cause other than problems of tolerability (as defined above), (c) switch to analgesic treatment with a drug other than an opioid or switch to a strong opioid after treatment with a weak opioid, (d) loss to follow-up, and (e) all-cause death. The analysis did not include the EMR of patients who dropped out of the study because of problems with tolerability, as defined above.

Disease Burden

As an approximation to the disease burden, we obtained (a) the change in pain intensity on a pain numeric rating scale of 11 points (0 no pain, 10 worst possible pain) [24]; (b) functional variations in the basic activities of daily living (BADL) using the Barthel index [27]; (c) cognitive changes using the Mini-Mental State Examination scale (MMSE) [28] between the nearest date before the start date (index date) and the end date of the study; (d) the following comorbidity variables (ICD-10-CM): high blood pressure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular event, heart failure, kidney failure, asthma, COPD, dementia, anxiety, depression, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis and malignancy (all types), smoking (daily smoker), and alcohol consumption of greater than 30 g alcohol/day; (e) as a summary variable of general comorbidity, for each patient, the Charlson comorbidity index was used as an approximation to severity [29], and the number of chronic comorbidities mentioned above were measured. Comorbidities and their severity were obtained at the index date. The scales were used in their validated Spanish versions and the absolute change in their natural and relative units was calculated as the percentage change from baseline. For BADL, the criterion of the interpretation of Barthel's scale was followed, considering relevant dependency as a severe-to-total limitation on functionality (limit corrected by covariates no greater than 60 points) [27]. For cognitive functioning, a score on the MMSE of less than 20 [28] was interpreted as a moderate-to-severe cognitive deterioration (cognitive deficit). Finally, the number of all-cause deaths was recorded from the index date with an NSAID and the subsequent follow-up with a weak or strong opioid, and during the 3 years’ follow-up after opioid initiation.

Disease Cost

The Spanish NHS perspective was used to calculate healthcare resource use and related costs. Therefore, only healthcare costs funded by the Spanish NHS relating to healthcare activity (medical visits, days of hospitalization, emergency visits, diagnostic and laboratory tests, referral to specialist and/or pain clinic, and therapeutic requests including drugs to treat pain, rehabilitation, and surgical procedures) carried-out by healthcare professionals were included in the analysis. Costs were expressed in 2018 euros as adjusted mean costs per patient throughout the study period and were calculated by multiplying the unit price/cost of every healthcare resource by the frequency of use during the follow-up. In addition, costs were expressed as the mean daily cost per patient. The costs are presented in aggregate form and separated by healthcare resource, analgesia cost, and type of analgesia (non-narcotic, weak opioid, and strong opioid). Supplementary Table S1 shows the unit costs of healthcare resources applied in the economic evaluation in 2018 euros and Supplementary Table S2 shows the type of opioids dispensed during the study. Prices were based on hospital accounting, except drugs, which were quantified using the retail price per pack at the time of dispensing from the community pharmacy (according to the Drug Catalogue of the General Council of Associations of Official Pharmacists of Spain) [30].

To calculate the annual healthcare budget of moderate-to-severe chronic refractory OA pain funded by the NHS in 1 year (2018), the healthcare cost per patient per year was multiplied by the estimated number of OA refractory patients in Spain in 2018, which was abstracted from the present work (Fig. 1). To estimate the number of patients in 2018, the incidence of initiating an opioid therapy with either a weak or strong opioid in 2010–2015 as shown by the OPIOIDS study [23] was projected onto the Spanish population aged 18 years or more in 2018, fitting the best trend analysis and corresponding mathematical equation (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S2). The statistical interpretation of the evolution of the incidence rate was made using trend analysis, accepting trends with an R2 value of at least 0.7 as relevant (the best fitted equations were linear and had an R2 between 0.96 and 0.99). Once the number of patients with moderate-to-severe chronic OA pain initiating an opioid per year was estimated, the number of such patients considered refractory to sequential therapy with an NSAID plus an opioid (pain severity 5 or higher), as found in the present analysis of the OPIOIDS study, was calculated.

Compliance with Ethics and Reporting Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Patient consent was not obtained as Spanish legislation excludes existing data that are aggregated for analysis and personal data are de-identified as specified in Spanish Law 15/1999, of 13 December, on Personal Data Protection. The study was classified by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products as EPA-OD (Post-authorization study with other design on February 14, 2019) and subsequently approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Terrassa, Barcelona, Spain, (Code: PFI-OP-2018-01) on March 11, 2019. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for reporting observational studies were followed in writing the manuscript [31].

Statistical Analysis

The data was validated in the BIG-PAC database® by computer sentences (specific scripts) and, in addition, in the study database the data was carefully reviewed using exploratory analysis. Likewise, in the preparation of data for analysis, the frequency distributions were observed, searching for possible registration or coding errors. External representativity of the database is also guaranteed [32]. A descriptive univariate statistical analysis was performed, and absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for qualitative data. Quantitative data were expressed using means, standard deviation, median, and the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution (interquartile range). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to estimate the parameters based on the total number of subjects with non-missing values. Statistical tests were used for paired groups (means, proportions). The before–after differences are presented with the 95% CI of the difference calculated by non-parametric resampling (1000 bootstrap iterations). A univariate linear model adjusted for confounders was used to compare healthcare costs when independent groups were compared. Covariates included were sex, age, general comorbidity (number and Charlson index), and time from diagnosis. The Bonferroni correction was applied in the case of multiple comparisons. The frequency of all-cause deaths (in percentages) and fatality rates of patients with refractory OA taking opioids during the 3-year follow-up was expressed as the number of all-cause deaths per 1000 patients with OA and chronic (more than 3 months) pain per year. The Mantel–Haenszel chi2 test was used to compare unadjusted mortality rates and a Cox proportional hazard model was fitted to compare adjusted mortality rates between NSAID plus weak opioid vs. NSAID plus strong opioid. The hazard ratio was calculated by adjusting for the time from the diagnosis of chronic pain, opioid persistence (days), pain severity at initiation of the opioid, age (years), sex, number of comorbidities, Charlson index, number of analgesics taken concomitantly with the opioid, NSAID taken concomitantly with opioid (yes/no), smoking, alcohol consumption, and body mass index. The IBM SPSS, version 23.0, NY, USA software program for statistical processing, was used (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software).

Results

Of the 1,280,684 patients aged at least 18 years who sought care during the recruitment period, 124,798 had a diagnosis of OA in any joint with chronic pain, representing a prevalence of 9.74% (95% CI 9.69–9.80%). Of these, 13,317 or 1.04% (1.02–1.06%) of patients who sought attention or 10.7% (10.5–10.8%) of patients with chronic moderate to severe OA pain were considered refractory to sequential treatment with an NSAID plus an opioid; 58.1% NSAID plus weak opioid and 41.9% NSAID plus strong opioid, and who met the criteria for inclusion in this secondary analysis of the OPIOIDS study (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics and general comorbidity of study patients; the mean age was 68.9 (SD 14.7) years and 71.3% (70.5–72.1%) were female. The joints with OA were as follows: 54.8% hip/knee, 24.8% spine, and 20.4% other joints. Overall mean treatment duration was 188.6 (185.4–191.8) days with NSAIDs followed by 400.6 (393.7–407.5) days with opioids: 200.3 (195.9–204.7) days with NSAIDs followed by 425.5 (416.1–434.9) days with weak opioids, and 172.4 (167.6–177.2) days with NSAIDs followed by 366.2 (356.1–376.3) days with strong opioids. The mean MPR was 73.4% (71.9–74.9%) and was significantly higher in patients on weak (76.6%; 75.1–78.1%) rather than strong opioids (71.6%; 69.7–72.7%), p < 0.001. The mean number of comorbidities was 2.9 (1.8) and the Charlson index was 1.8 (1.7). The prevalence of the most frequent comorbidities is shown in Table 1. Although opioids are not recommended in these patients, 1.7% (1.5–1.9%) were diagnosed with chronic alcoholism. In general, patients who received a weak opioid had fewer comorbidities (except dyslipidemia and obesity) and severity according to the Charlson index (Table 1). Table 2 shows the disease burden of this cohort of patients. Pain severity fell by 0.9 points on average (relative reduction of 12.2% [95% CI 11.6–12.8%]), cognitive impairment increased by 2.2 points (9.1%, with 4.3% [4.0–4.7%] more patients with cognitive deficits), and the Barthel index worsened by 0.4 points (0.5%, with 2.3% [2.1–2.6%] more patients with severe-to-total dependence) over a median treatment persistence of 182 (84–719) days on opioids, with those on weak opioids having greater persistence; 195 (86–935) days vs. 170 (83–542) days, p < 0.001. Although the differences were small, patients receiving weak opioids showed a greater increase in the proportion of patients with cognitive impairment and the degree of dependence than those who received strong opioids (p < 0.01). The mean unadjusted all-cause mortality rate/1000 patient-years was 1.66 (1.46–1.89) times greater in those on strong compared with weak opioids; 30.98 (28.37–33.76) vs. 18.67 (16.95–20.51) deaths/1000 patient-years, p < 0.001 (Table 2). On average, the adjusted mortality rate was 44% higher in patients on strong rather than weak opioids; hazard ratio 1.44 (95% CI 1.26–1.65), p < 0.001 (Fig. 2).

All-cause mortality rate by type of opioid throughout the follow-up. HR hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval adjusted for time from diagnosis of chronic pain, opioid treatment duration, severity of pain at opioid initiating therapy, age (years), sex, number of comorbidities, Charlson index, number of analgesics taken concomitantly with the opioid, NSAID taken concomitantly with opioid, smoking, alcohol consumption, and body mass index HR: 1.44 (1.26–1.65); p < 0.001

Table 3 details the analgesic medication prescribed during the follow-up periods and the adherence rate of opioids, and Supplementary Table S2 shows the opioids administered and the medical specialty initiating the prescription. During the 12 months before initiation of opioids, the mean number of concomitant drugs was 2.0 (SD 0.7) analgesics per patient, which increased significantly to 2.2 (0.8) at 36 months (p < 0.001) and was more marked in patients receiving weak opioids. This increase is explained not only by the addition of opioids but also because the effects of NSAIDs are not replaced by opioids, and an increase in NSAIDs was observed at 24 and 36 months compared with the 12 months after opioid initiation (Table 3). Virtually all weak opioid prescriptions were for tramadol or tramadol plus paracetamol; 97.9%. The most dispensed opioids were tramadol (57.2% if tramadol is included in combination and alone) and fentanyl (14.0%). Medical specialties who initiated most opioid prescriptions were family medicine (71.1%) and anesthesia/resuscitation (11.6%). Strong opioids were proportionately more prescribed by reference specialists (family medicine/specialist ratio in prescribing weak opioids 3.5 vs. 1.6 for strong opioids [Supplementary Table S2]). At 36 months, overall treatment adherence was 20.9% (20.2–21.6%); 23.7% (22.8–24.7%) for weak opioids and 17.0% (16.0–18.0%) for strong opioids, p < 0.001 (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Table 4 describes the mean healthcare resource use per patient in the 12 months before initiation of an opioid, the 12 months after initiation of an opioid, and throughout the study period (Supplementary Table S3 shows resource use according to the opioid-prescribing specialty). Overall, resource use was significantly lower with patients on NSAIDs plus weak opioid than in those receiving NSAIDs plus strong opioid, p < 0.001 in almost all health resource comparisons, with fewer rehabilitation sessions and laboratory tests in the 12 post-opioid months. Primary care medical visits were the most widely used resource and the only one that fell significantly with the addition of an opioid, while the use of the remaining health resources significantly increased with weak and strong opioid use (except hospital stays, laboratory tests, and axial tomography), although the magnitude of the increases in terms of the effect size was very small. Unsurprisingly, the frequency of specialist visits was significantly higher when the initial opioid prescription was made by specialists rather than the primary care physician, both before prescribing the opioid and in the 12 months after opioid initiation; 5.2 visits versus 1.2, p < 0.001 (Supplementary Table S3). A total of 7.6% (7.2–8.1%) patients underwent surgery, either outpatient or hospitalized for more than 24 h related to OA, with a significantly higher percentage in patients on strong opioids; 15.4% (14.5–16.4%) vs. 1.9% (1.6–2.2%), p < 0.001.

Healthcare costs as well as costs of non-narcotic analgesia and opioids per patient per day are shown in Table 5. At the end of the study period, the total cost was €17.95 million. The mean adjusted health cost per patient during the 12 months pre-opioid was €1628 (1587–1669), while during the following 12 months it was €2007 (1947–2068), p < 0.001. At 48 months, the mean cost per patient was €7350 (7193–7507), equivalent to €1838 per year, and was significantly higher in those on strong opioids; €9886 (€9608–10,164, €2472/year) vs. €5519 (€5349–5689, €1380/year), respectively, p < 0.001, due to the greater cost of health resources, but also the cost of opioids that clearly compensated for the reduction in the cost of non-narcotic analgesia (Table 5). The cost of analgesia represented 16.0% (11.3% with weak opioids and 19.6% with strong opioids) of health costs, while the cost of opioids accounted for 70.2% of the cost of analgesia (46.2% with weak opioids and 81.0% with strong opioids). The mean cost/day of analgesia at 48 months was €3.38 (€2.93–3.83); €0.46 for non-opioid analgesics (€0.45–0.47), and €2.92/day for opioids (€2.77–3.07); €0.88/day for weak opioids and €5.97/day for strong opioids.

The annual healthcare costs in 2010–2018 from the Spanish NHS perspective in patients with moderate-to-severe refractory chronic OA pain as defined in this secondary analysis of the OPIOIDS study are shown in Table 6. The projection of health costs to the national total according to the expected prevalence of patients with chronic moderate-to-severe pain due to OA and the subgroup of patients refractory to usual NSAID plus opioid treatment was €602 and €286 million/year in 2018, respectively. The costs of total analgesia and opioid analgesia were €56 million and €48 million, respectively, in patients refractory to NSAID plus opioid, and €132 million and €112 million in all patients with moderate to severe chronic pain due to OA.

Discussion

This was a secondary analysis of the OPIOIDS study [23], which estimated the disease burden and cost in patients with OA in any joint with chronic moderate-to-severe pain refractory to standard-of-care with an NSAID followed sequentially or concomitantly by an opioid drug, plus the usual non-pharmacological treatment recommended in Spain [25]. The analysis was carried out in conditions of usual medical practice, from the perspective of the NHS in Spain, which is a valuable source of information for health decision-makers that is based on real-world data. We found that 10.7% of all patients with chronic moderate-to-severe OA pain or 1% of people aged at least 18 years who sought care were refractory to treatment, resulting in a considerable disease burden and costs. In terms of the disease burden, refractory patients showed a modest reduction in pain, while presenting a considerable burden of comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and level of dependency in a relatively short treatment period; a median treatment persistence of 182 days on opioids. Wei et al. [33] showed evidence of the economic impact of opioid use and the small improvement in pain intensity, like our results. The increased costs did not correlate with an improvement in health, and a considerable increase in cognitive decline and the degree of dependence for the basic activities of daily living, of similar magnitude to that observed with some psychotropic drugs, was seen in a short period of time [34, 35]. The comorbidities observed, in terms of type and frequency, were in line with those observed by other authors. It is estimated that 59–87% of people with OA have at least one other chronic condition. We found that refractory patients had a mean of 2.9 comorbidities, compatible with the 2.6 moderate-to-severe comorbidities found in the study by van Dijk et al. [7], and 33.2% had four or more chronic conditions, similar to the findings of other studies [8, 9]. In addition, the prevalence of obesity in this cohort of patients with OA (27.8%) was substantially higher than the prevalence of obesity in the general Spanish population aged 15 years and over, which was 17.4%, according to the 2017 National Health Survey [36]. Non-harmonized metabolic syndrome was more common in patients with OA than in the general population (30.5% vs. 24.2%) [9, 37]. Cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and ischemic heart disease), osteoporosis, anxiety, and major depressive disorders were also more prevalent in these patients with refractory OA than in the general population [36]. Lastly, a potential risk for death related to opioid drugs, mainly strong opioids, has been identified in the literature, among other adverse events [38, 39]. In our study, we found a meaningful excess in all-cause mortality in comparison with the mortality rate of the general population in Spain by the National Institute of Statistics [40]: 9.1 deaths/1000 inhabitant-years in 2018 vs. 23.8 deaths/1000 patient-years in our study. Also, as has been found by others [39], the mortality rate was significantly associated with use of strong opioids compared with weak opioids; an excess of 44% on average.

The cost of the disease, expressed as healthcare costs funded by the NHS, increased significantly, and were considerable, particularly in patients on strong opioids; €1838 per patient per year (€2472 in patients receiving strong opioids and €1380 in those on weak opioids). Primary care medical visits were the most widely used resource and the only one that decreased significantly after the initiation of opioids, while other health resource utilization, particularly specialist visits in patients on strong opioids, although not hospital stays, laboratory tests, or axial tomography, increased significantly when patients were receiving weak or strong opioids, although the magnitude of the increases in terms of the effect size, according to Kazis et al., was small [41]. Nonetheless, our frequency data were consistent with those reported by the EPISER study (28.9%), which also found that medical visits were the healthcare resource most used by patients with rheumatic diseases [42]. Another Spanish study in patients with knee and hip OA (ARTROCAD) also found that the most important component of healthcare costs was medical visits, accounting for 24% of the total [43]. In our analysis, the use of almost all healthcare resources, especially medical visits, was significantly more common in patients on strong rather than weak opioids. In addition, as expected, the cost of analgesia (16% of the total healthcare cost) was significantly higher in patients on strong versus weak opioids; 20% vs. 11%, respectively. The highest analgesia cost together with more healthcare resource use explains the annual cost being significantly higher in patients receiving strong opioids. However, we found no similar report in the literature that enabled us to compare these findings. The projection of these costs to the national total, according to the expected prevalence of patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain due to OA, and in particular, patients refractory to usual treatment, is considerable for the Spanish NHS, reaching €602 million and €286 million per year in 2018, or 0.9% and 0.4% of total public health expenditure, respectively [44]. A review by Xie et al. [45] found that direct costs (mean/year) in the USA ranged between $1442 and $21,335 and concluded that the costs of OA are considerable. Salmon et al. [46], and Chen et al. [47], also highlighted the heterogeneity of studies and the lack of methodological consensus in obtaining comparable estimates of the disease cost and underlined the high healthcare costs (€500–10,900) of OA.

Up to 15% of patients with moderate-to-severe pain may be resistant to drug treatment, and specialized pain treatment [20, 21]. However, it should be considered before classifying patients as refractory that sometimes the diagnosis is made after a deficient evaluation and/or an incorrect use of non-pharmacological and/or pharmacological treatments [48]. In other cases, “refractory” may be used to describe all patients who require more specialized treatment [48, 49]. A review by Borsook [50] shows the wide range of potential factors and interactions (bio-psycho-social) that may cause patients to become refractory to treatment. Therefore, the definition may cause disagreement. According to our study criteria, the percentage of patients with refractory pain could be underestimated. First, because this type of pain is difficult to control, with clinical problems in determining the intensity, the development of drug tolerance, and other unconsidered factors. Secondly, because we could not quantify the different clinical scales used to measure pain and other health outcomes in all patients.

A successful treatment for chronic pain may, in our view, always depend on adequate follow-up and monitoring that permit the adjustment of the therapeutic strategy to the analgesic needs. Depending on the results, the World Health Organization (WHO) pain scale becomes, in many cases, a barrier to the proper treatment of many types of pain, as it follows pharmacological steps until the best drug for the individual is found. Refractory pain management is a challenge to all parts of the healthcare system to correctly use the available pharmacological arsenal, including referring these patients to pain units. There seems to be a pharmacological gap in this group of patients, which may be solved by new types of drugs that could control the pain, without resorting to interventional or surgical strategies. The data suggest high consumption of weak and strong opioids, which is continuing to increase, for the treatment of refractory chronic pain associated with OA, even though neither OARSI nor the ACR recommends them, but rather they emphasize the use of non-pharmacological measures. This is because they consider the benefit/risk of current drug treatments to be weak [18, 19], particularly as two-thirds of patients with chronic OA pain are aged 65 years or more according to the Spanish National Health Survey 2017 [36], and that this population group is more prone to use NSAIDs or opioids [34, 35]. However, our study highlights the increase in this group, in line with current trends around the world [22, 51, 52]. We do not know if health professionals have made an individual valuation (benefit–risk) before starting treatment, although this kind of treatment was common and seems to be increasing. As an example, Ackerman et al. [52] quantified the current use of opioids for OA pain in Australia and concluded that OA-related opioid use will continue to increase substantially, and that these projections represent a conservative estimate of the total financial burden, given the costs associated with the adverse effects of these drugs, especially in older people [34, 35]. Except for methodological differences, our results are in line with the literature reviewed, and are worrisome given the fact that the expected trend in future utilization of opioid drugs in Spain is increasing considerably [22, 53]; then, as population aging progresses, one may anticipate a substantial increment in health expenditures but also more disability for patients with OA and premature death. It is also worrisome that despite recommendations from scientific societies, it seems that, to date, there are no specific measurements from health authorities to counterbalance such an increment in opioid utilization. Perhaps, and as mentioned above, novel analgesic therapies based on antibodies that inhibit the function of nerve growth factor that should be available soon could minimize the epidemic of opioid use [53, 54].

Study Limitations

The possible limitations of the study affect those of all retrospective studies, such as the under-recording of the disease or the possible variations in professionals and patients as a result of the observational design, and even the measurement system used for the main variables, or the possible existence of classification or selection bias. In this respect, the possible inaccuracy of the definition of refractory pain in the diagnosis of OA, or missing variables that could have influenced the results, should be considered as limitations. Another possible limitation was due to treatment discontinuation because of poor tolerability being assumed after more than 30 days without renewing the initial medication dispensed in the community pharmacy and without refills during the study follow-up, whereas in cases of abandonment the cause could not be identified, and possible combinations of analgesic medication with other non-pharmacological therapies were not taken into account. Another possible limitation refers to considering patients who continued to show a pain intensity of 5 or higher on the pain scale after the NSAID plus opioid sequence as refractory, regardless of the relative reduction in pain intensity. We suggest, as do other authors [46,47,48], that a pain intensity of greater than 5 is enough to consider that the therapeutic goal of pain reduction has not been achieved. In our study, only 246 of the 2782 patients (8.8%) who continued to be treated with the initial opioid at 36 months showed a reduction in pain of more than 30% of the baseline value, and only 72 (2.6%) achieved a reduction of 50% or higher, which means that despite continuing treatment with an opioid, patients with OA and chronic pain require further reductions in than those conferred by the NSAID plus opioid treatment sequence.

Despite these limitations, the strengths of the study include the lack of observational studies in real-world conditions in the literature consulted, which makes it difficult to compare the results but enhances the value of this study. In addition, the fact that the study included a large number of subjects from seven Spanish Autonomous Communities increases the representativeness of the results and, therefore, their extrapolation to the entire Spanish NHS. Moreover, the incidence of initiation of treatment of OA with opioids in the study period (2010–2015, both included) shows parallels and magnitudes similar to the study of opioid use in Spain recently carried out by the Spanish Medicines Agency [22], which supports the reliability of the results.

Conclusions

Further studies in usual clinical practice will be required to reinforce the consistency of our results. That is, the treatment of refractory pain due to OA can increase health costs without ostensibly improving pain control and worsening the disease burden in terms of cognitive functioning and the basic activities of daily living. Also, and compared with general population, an excess in all-cause deaths was observed particularly in those taking strong opioids. New therapeutic approaches to the treatment of refractory pain may be necessary, especially in patients most refractory to existing drugs. In conclusion, in usual clinical practice, there was an appreciable percentage of patients with OA refractory to usual pharmacological treatment, which was accompanied by high healthcare costs for the Spanish NHS, while the disease burden worsened substantially in a relative short period of treatment.

References

National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014.

Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araújo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19:1270–85.

O’Neill TW, McCabe PS, McBeth J. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors and disease outcomes of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:312–26.

Martel-Pelletier J, Maheu E, Pelletier JP, et al. A new decision tree for diagnosis of osteoarthritis in primary care: international consensus of experts. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31:19–30.

Blanco FJ, Silva-Díaz M, Quevedo Vila V, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic osteoarthritis in Spain: EPISER2016 study. Reumatol Clin. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2020.01.008.

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333.

van Dijk GM, Veenhof C, Schellevis F, et al. Comorbidity, limitations in activities and pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:95.

Kadam UT, Jordan K, Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in patients with osteoarthritis: a case-control study of general practice consulters in England and Wales. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:408–14.

Puenpatom RA, Victor TW. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with osteoarthritis: an analysis of NHANES III data. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:9–20.

Hawker GA. Osteoarthritis is a serious disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(Suppl. 120):S3–6.

Reginster JY, Reiter-Niesert S, Bruyère O, et al. Recommendations for an update of the 2010 European regulatory guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products used in the treatment of osteoarthritis and reflections about related clinically relevant outcomes: expert consensus statement. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:2086–93.

Nees TA, Schiltenwolf M. Pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis-related pain. Schmerz. 2019;33:30–48.

Majeed MH, Sherazi SAA, Bacon D, Bajwa ZH. Pharmacological treatment of pain in osteoarthritis: a descriptive review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:88.

Mosleh W, Farkouh ME. Balancing cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks in patients with osteoarthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A summary of guidelines from an international expert group. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:68–75.

Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, et al. Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD013273. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013273.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Service U S Department of Health and Human Services. Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30:138–40.

Dennis BB, Bawor M, Naji L, et al. Impact of chronic pain on treatment prognosis for patients with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse. 2015;9:59–80.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:1578–89.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(2):149–62.

Keßler J, Geist M, Bardenheuer H. Treatment-refractory pain. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2018;143:1372–80.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000435.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Utilización de medicamentos opioides en España durante el periodo 2010–2018 (Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Utilization of opioid drugs in Spain in the period 2010–2018). https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/observatorio-de-uso-de-medicamentos/utilizacion-de-medicamentos-opioides-en-espana-durante-el-periodo-2010-2018. Accessed Jan 2020.

Sicras-Mainar A, Tornero-Tornero C, Vargas-Negrín F, Lizarraga I, Rejas-Gutierrez J. Health outcomes and costs in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic pain treated with opioids in Spain: The OPIOIDS Real World study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X20942000.

Vicente Herrero MT, Delgado Bueno S, Bandrés Moyá F, Ramírez Iñiguez de la Torre MV, Capdevila García L. Valoración del dolor. Revisión comparativa de escalas y cuestionarios (Valuation of pain. Comparative Review of scales and questionnaires). Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2018; 25:228–36.

Blanco García FJ. Tratamiento de la artrosis (Treatment of Osteoarthritis). En Manual SER de Enfermedades Reumáticas (Handbook SER on Rheumatic Diseases). 4ª edición. Blanco García FJ, Carreira Delgado P, Martín Mola E y otros ed. Editorial Médica Panamericana. Madrid 2004: 325–30.

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–7.

Mahoney FI, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Maryland State Med J. 1965;14:56–61.

Lobo A, Saz P, Marcos G, et al. Revalidation and standardization of the cognition mini-exam (first Spanish version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination) in the general geriatric population. Med Clin (Barc). 1999;112(20):767–74.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Consejo General de Colegios de Farmacéuticos Oficiales de España (General Council of Official Pharmaceutical Colleges of Spain). Base de Datos del Conocimiento Sanitario (Database on Health Knowledge). https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.aspx. Accessed Sep 2019.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9.

Sicras-Mainar A, Enríquez JL, Hernández I, Sicras-Navarro A, Aymerich T, León M. Validation and representativeness of the Spanish BIG-PAC database: integrated computerized medical records for research into epidemiology, medicines and health resource use (real word evidence). Value Health. 2019;Supplement 3:S734.

Wei W, Gandhi K, Blauer-Peterson C, Johnson J. Impact of pain severity and opioid use on health care resource utilization and costs among patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25:957–65.

Lewis PR, Karpa KD, Felix TM, Lewis PR. Adverse effects of common drugs: adults. FP Essent. 2015;436:23–30.

Boparai MK, Korc-Grodzicki B. Prescribing for older adults. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(4):613–26.

Ministerio de sanidad, consumo y bienestar social—Encuesta Nacional de Salud España 2017 (Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare—2017 Spanish National Health Survey). https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuesta2017.htm. Accessed June 2020.

Martínez-Larrad MT, Corbatón-Anchuelo A, Fernández-Pérez C, Lazcano-Redondo Y, Escobar-Jiménez F, Serrano-Ríos M. Metabolic syndrome, glucose tolerance categories and the cardiovascular risk in Spanish population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;114:23–31.

Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Phys. 2008;11:S105e20.

Pilgrim JL, Yafistham SP, Gaya S, Saar E, Drummer OH. An update on oxycodone: lessons for death investigators in Australia. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2015;11:3e12.

INE (National Institute on Statistic of Spain), 2018. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176780&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573175. Accessed June 2020.

Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27(suppl):S178–89.

Seoane-Mato D, Martínez Dubois C, Moreno Martínez MJ, Sánchez-Piedra C, Bustabad-Reyes S; en representación del Grupo de Trabajo del Proyecto EPISER2016. Frecuencia de consulta médica por problemas osteoarticulares en población general adulta en España. Estudio EPISER2016. Gac Sanit. 2019. Gac Sanit. 2019: S0213-9111(19)30150-5.

Loza E, Lopez-Gomez IM, Abasolo L, Maese J, Carmona L, Batlle-Gualda E. Economic burden of knee and hip osteoarthritis in Spain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:158–65.

Rodríguez Blas MC. Dirección General de Cartera Común de Servicios del SNS y Farmacia. Secretaría General de Sanidad. Ministerio de Sanidad. Estadística de Gasto Sanitario Público 2018. 2018. (General Directorate of common Services scheme of the National Health System and Pharmacy. General Secretary of Health. Ministry of Health. Statistic of Public Health expenditure 2018) https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/EGSP2008/egspPrincipalesResultados.pdf. Accessed: June 2020.

Xie F, Kovic B, Jin X, He X, Wang M, Silvestre C. Economic and humanistic burden of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of large sample studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:1087–100.

Salmon JH, Rat AC, Sellam J, et al. Economic impact of lower-limb osteoarthritis worldwide: a systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24:1500–8.

Chen A, Gupte C, Akhtar K, Smith P, Cobb J. The global economic cost of osteoarthritis: how the UK compares. Arthritis. 2012;2012:698709.

Deer TR, Caraway DL, Wallace MS. A definition of refractory pain to help determine suitability for device implantation. Neuromodulation. 2014;17:711–5.

Smith BH, Torrance N, Ferguson JA, Bennett MI, Serpell MG, Dunn KM. Towards a definition of refractory neuropathic pain for epidemiological research. An international Delphi survey of experts. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:29.

Borsook D, Youssef AM, Simons L, Elman I, Eccleston C. When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain. 2018;159:2421–36.

Kalkman GA, Kramers C, van Dongen RT, van den Brink W, Schellekens A. Trends in use and misuse of opioids in the Netherlands: a retrospective, multi-source database study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e498–505.

Ackerman IN, Zomer E, Gilmartin-Thomas JF, Liew D. Forecasting the future burden of opioids for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26:350–5.

Rejas-Gutierrez J, Sicras-Mainar A, Darbà J. Future projections of opioids utilization and cost in patient with chronic Osteoarthritis pain in Spain. Value Health 2020; PDG 28. ISPOR Europe 2020, November 14–18, 2020; Milan, Italy.

Wise BL, Seidel MF, Lane NE. The evolution of nerve growth factor inhibition in clinical medicine. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-00528-4.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The OPIOIDS study was funded by Pfizer, SLU, and the sponsor also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

The study was conceived by ASM (ansicras@atryshealth.com), JRG (javier.rejas@pfizer.com) and IL(Isabel.lizarraga@pfizer.com).) ASM, CTT (carlostornero@gmail.com), FVN (fvargasnegrin@gmail.com), JRG, ASN (arsicras@atryshealth.com) and IL participated and contributed to the design of the study. Data collection and statistical analysis was made by ASM and ASN. Interpretation of data was made by all authors. All authors drafted or revised critically and approved the final version of submitted manuscript.

Prior Presentation

The content of the manuscript has been shared as a poster (“Burden and cost-of-disease in chronic osteoarthritis pain patients refractory to standard of care in Spain: Further outcomes of the opioids study”) in the Virtual ISPOR Europe Congress (16–19 November 2020).

Disclosures

Antoni Sicras-Mainar and Aram Sicras-Navarro are employees of Atrys Health SA who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with this manuscript. Javier Rejas-Gutiérrez and Isabel Lizarraga are employees of Pfizer, SLU. Juan Carlos Tornero-Tornero and Francisco Vargas-Negrín declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. The authors state that the manuscript is based on an investigation classified by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) as a Post-Authorization Study—Other Design (EPA-OD) on February 14, 2019, and was approved by the Institutional Research Board of the Hospital de Terrassa in Barcelona (Code: PFI-OP-2018-01) on March 11, 2019. Patient consent was not obtained as Spanish legislation excludes existing data that are aggregated for analysis and personal data are de-identified as specified in Spanish Law 15/1999, of 13 December, on Personal Data Protection.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sicras-Mainar, A., Rejas-Gutierrez, J., Vargas-Negrín, F. et al. Disease Burden and Costs in Moderate-to-Severe Chronic Osteoarthritis Pain Refractory to Standard of Care: Ancillary Analysis of the OPIOIDS Real-World Study. Rheumatol Ther 8, 303–326 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00271-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00271-y