Abstract

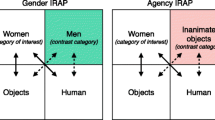

The IRAP (Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure) is a procedure developed for the assessment of beliefs, attitudes, and other implicit cognitive elements. Stimuli-related variables that influence IRAP performance have been studied, but not the influence of social situation variables of the test itself. Gender stereotypes are one of the implicit beliefs most studied with the IRAP. Gender bias relational responses may be brought under the functional control of situational social variables, such as responding in a mixed gender group or responding in a single gender group (women only/men only). One hundred and ten undergraduates (65 women and 45 men; aged 18–22) performed a collective IRAP application about gender stereotypes. In the first experimental condition, the test was applied in mixed gender groups. In the second experimental condition, the test was applied in single gender groups. The results showed that gender stereotypes were present in men’s and women’s responses to the IRAP. Both male and female participants showed greater gender bias when responding in single gender groups than in mixed gender groups in all the IRAP trial types. The social context in which IRAP was applied influenced the participant's performance. The advantages of collective IRAP applications are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Power, P., Hayden, E., Milne, R., & Stewart, I. (2006). Do you really know what you believe? Developing the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a direct measure of implicit beliefs. Irish Psychologist, 7(32), 169–177.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., & Boles, S. (2010). A sketch of the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the relational elaboration and coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record, 60(3), 527–542.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Hayden, E., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2008). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a response-time and event-related- potentials methodology for testing natural verbal relations: A preliminary study. The Psychological Record, 58(4), 497–516.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Murphy, A., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2010). The implicit relational assessment procedure: Exploring the impact of private versus public contexts and the response latency criterion on pro-white and anti-black stereotyping among white Irish individuals. The Psychological Record, 60, 57–80.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Waldron, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2009). Testing the validity of the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the implicit association test (IAT): Measuring attitudes towards Dublin and country life in Ireland. The Psychological Record, 59, 389–406.

Bast, D. F., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2015). Developing an individualized implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a potential measure of self-forgiveness related to negative and positive behavior. The Psychological Record, 65(4), 717–730.

Blum, R. W., Mmari, K., & Moreau, C. (2017). It begins at 10: How gender expectations shape early adolescence around the world. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S3–S4.

Castillo-Mayén, R., & Montes-Berges, B. (2014). Análisis de los estereotipos de género actuales. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1044–1060.

Daniels, E. A., Layh, M. C., & Porzelius, L. K. (2016). Grooming ten-year-olds with gender stereotypes? A content analysis of preteen and teen girl magazines. Body Image, 19, 57–67.

Dawson, D. L., Barnes-Holmes, D., Gresswell, D. M., Hart, A. J. P., & Gore, N. J. (2009). Assessing the implicit beliefs of sexual offenders using the implicit relational assessment procedure: A first study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research & Treatment, 21(1), 57–75.

Döring, N., Reif, A., & Poeschl, S. (2016). How gender-stereotypical are selfies? A content analysis and comparison with magazine adverts. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(B), 955–962.

Fernandez, J., Quiroga, M. A., Escorial, S., & Privado, J. (2014). Explicit and implicit assessment of gender roles. Psicothema, 26(2), 244–251.

Finn, M., Barnes-Holmes, D., Hussey, I., & Graddy, J. (2016). Exploring the behavioral dynamics of the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure: The impact of three types of introductory rules. Psychological Record, 66, 309–321.

García-Vega, E., Menéndez Robledo, E., García Fernández, P., & Rico Fernández, R. (2010). Influencia del sexo y del género en el comportamiento sexual de una población adolescente. Psicothema, 22(4), 606–612.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. an improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (Eds.). (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). A functional approach to the study of implicit cognition: The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the relational elaboration and coherence (REC) model. In S. Dymond & B. Roche (Eds.), Advances in relational frame theory and contextual behavioural science (pp. 97–125). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Instituto de la Juventud (INJUVE) (2010). Jóvenes y sexo, el estereotipo que obliga y el rito que identifica [Youth and gender, the stereotype that obligate and the rite that identify]. Retrieved from http://injuve.es/sites/default/files/jovenes_y_sexo.pdf).

Kavanagh, D., Hussey, I., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016). Using the IRAP to explore natural language statements. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(4), 247–251.

McKenna, I., Hughes, S., Barnes-Holmes, D., De Schryver, M., Yoder, R., & O'Shea, D. (2016). Obesity, food restriction, and implicit attitudes to healthy and unhealthy foods: Lessons learned from the implicit relational assessment procedure. Appetite, 100, 41–54.

Nicholson, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2012). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a measure of spider fear. The Psychological Record, 62, 263–278.

Nicholson, E., Hopkins-Doyle, A., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, R. A. P. (2014). Psychopathology, anxiety or attentional control: Determining the variables which predict IRAP performance. The Psychological Record, 64, 179–188.

Nicholson, E., McCourt, A., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a measure of obsessive beliefs in relation to disgust. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2, 23–30.

Parling, T., Cernvall, M., Stewart, I., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Ghaderi, A. (2012). Using the implicit relational assessment procedure to compare implicit pro-thin/anti-fat attitudes of patients with anorexia nervosa and non-clinical controls. Eating Disorders, 20(2), 127–143.

Power, P., Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2009). The implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) as a measure of implicit relative preferences: A first study. The Psychological Record, 59(4), 621–640.

Roddy, S., Stewart, I., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2011). Facial reactions reveal that slim is good but fat is not bad: Implicit and explicit measures of body-size bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(6), 688–694.

Rudman, L. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2004). Gender differences in automatic in-group bias: Why do women like women more than men like men? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 87(4), 494–509.

Scanlon, G., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2014). Using the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) to assess implicit gender bias and self-esteem in typically-developing children and children with ADHD and with dyslexia. Behavioral Development Bulletin, 19(2), 48–59.

Skowronski, J. J., & Lawrence, M. A. (2001). A comparative study of the implicit and explicit gender attitudes of children and college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(2), 155–165.

Vahey, N. A., Nicholson, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2015). A meta-analysis of criterion effects for the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) in the clinical domain. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 48, 59–65.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. In this informed consent, participants were told that they were invited to collaborate in a test about reaction times, but they were not told that the aim of the investigation was to study the different reaction times in single gender versus mixed gender groups. It was assumed that this mild deception does not involve ethical consequences. This research was ethically approved by the Department of Psychology at the University of Oviedo.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Instructions of the IRAP Read by the Researchers

Instructions | |

“Good afternoon to all and thank you for coming. We are going to test your reaction times in front of certain stimuli. We are going to explain now what the test is about. We need you to pay close attention. Pairs of words are going to appear on the screen, one at the top of the screen and other at the bottom of the screen. You will have to choose if these two words are related or if they are not. You will not have to answer what you think about whether they are related or not, but what we tell you to answer. That is, you will have to adjust your answers to what the instructions ask you to answer in each case. Sometimes you will be asked to answer according to certain typical or usual stereotypes, and sometimes you will be asked for the opposite. In this case, you will find that it is more difficult to answer, but this is the aim of the current investigation. Look at this example (draw “spider” at the top of the blackboard and “ugly” at the bottom of the blackboard). When you will be asked to answer according to the stereotypes you must answer that the relation is true, whereas when you will be asked to do the opposite, that is, against common stereotypes, you must answer that the relation is false. Let’s see another example (draw “flower” at the top of the blackboard and “ugly” at the bottom of the blackboard). If you are told to follow the stereotypes you must answer that it is false, whereas if you are asked to do the opposite, you must answer that it is true. If you fail you will see a cross indicating that your answer is wrong, and you will have to answer correctly in order to follow. Do not worry, it's easier than it looks. In addition, you will have some practice trials to familiarize yourself with the rules of the test. Remember that this is not a questionnaire to measure your opinions, but a test to see how you follow these rules. Also, it is important that you respond as quickly as you can. Once the test starts no questions will be allowed, so do not raise your hand. In case of doubt, respond what seems more correct to you. When the test has been finished, please remain in your seat, do not raise your hand or speak, and wait new instructions from the researchers.” |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Errasti, J., Martinez, H., Rodriguez, C. et al. Social Context in a Collective IRAP Application about Gender Stereotypes: Mixed Versus Single Gender Groups. Psychol Rec 69, 39–48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-018-0320-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-018-0320-1