Abstract

Background

There is paucity of data describing the rate and quality indices of antibiotics used among hospitalized patients at continental level in Africa. This systematic review evaluated the pooled prevalence, indications, and types of antibiotics used in hospitals across Africa.

Methods

Three electronic databases, PubMed, Scopus, and African Journals Online (AJOL), were searched using search terms. Point prevalence studies of antibiotic use in inpatient settings published in English language from January 2010 to November 2022 were considered for selection. Additional articles were identified by checking the reference list of selected articles.

Results

Of the 7254 articles identified from the databases, 28 eligible articles involving 28 studies were selected. Most of the studies were from Nigeria (n = 9), Ghana (n = 6), and Kenya (n = 4). Overall, the prevalence of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients ranged from 27.6 to 83.5% with higher prevalence in West Africa (51.4–83.5%) and North Africa (79.1%) compared to East Africa (27.6–73.7%) and South Africa (33.6–49.7%). The ICU (64.4–100%; n = 9 studies) and the pediatric medical ward (10.6–94.6%; n = 13 studies) had the highest prevalence of antibiotic use. Community-acquired infections (27.7–61.0%; n = 19 studies) and surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) (14.6–45.3%; n = 17 studies) were the most common indications for antibiotic use. The duration of SAP was more than 1 day in 66.7 to 100% of the cases. The most commonly prescribed antibiotics included ceftriaxone (7.4–51.7%; n = 14 studies), metronidazole (14.6–44.8%; n = 12 studies), gentamicin (n = 8 studies; range: 6.6–22.3%), and ampicillin (n = 6 studies; range: 6.0–29.2%). The access, watch, and reserved group of antibiotics accounted for 46.3–97.9%, 1.8–53.5%, and 0.0–5.0% of antibiotic prescriptions, respectively. The documentation of the reason for antibiotic prescription and date for stop/review ranged from 37.3 to 100% and 19.6 to 100%, respectively.

Conclusion

The point prevalence of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa is relatively high and varied between the regions in the continent. The prevalence was higher in the ICU and pediatric medical ward compared to the other wards. Antibiotics were most commonly prescribed for community-acquired infections and for SAP with ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and gentamicin being the most common antibiotics prescribed. Antibiotic stewardship is recommended to address excessive use of SAP and to reduce high rate of antibiotic prescribing in the ICU and pediatric ward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Antimicrobial resistance remains a major public health challenge in the twenty-first century [1,2,3]. It threatens the use of antibiotics for the prevention of infections due to surgery, dialysis, and chemotherapy [4]. Infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens are associated with high mortality rate [5, 6] and significant morbidity and healthcare costs [3]. Infections caused by resistant pathogens, especially the multidrug-resistant pathogens, are difficult to treat due to limited number of effective antibiotics [6, 7]. Infections due to antibiotic-resistant pathogens cause an estimated 700,000 deaths per year, and this was estimated to increase to about 10 million deaths per year by the year 2050 [8]. This calls for interventions to reduce the burden of antibiotic resistance in healthcare system. Inappropriate use of antibiotics contributes to the emergence and transmission of antibiotic-resistant pathogens [9]. Evidence has shown that about 20–50% of antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate, and this increases the risk of antibiotic resistance [10]. Antimicrobial stewardship program is used as a strategy to tackle inappropriate antibiotic prescription in healthcare facilities and prevent antibiotic resistance [11]. Evidence has demonstrated the effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship in improving antibiotic prescribing practices among prescribers and improving clinical and microbial outcomes [12, 13]. In addition, antimicrobial stewardship has been shown to reduce healthcare cost among patients [14].

Evaluation of antibiotic prescribing pattern among patients in healthcare facilities is used to identify antimicrobial stewardship opportunities to improve appropriate use of antibiotics [15]. Point prevalence studies have been found to be valid and reliable in measuring antibiotic use among hospitalized patients [16]. Available evidence has shown that about 30% and 50% of hospitalized patients in Europe and the USA use at least one antibiotics per day [17, 18]. In Africa, several point prevalence studies have reported high rate of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients and inappropriate use of antibiotics in healthcare facilities [19,20,21,22]. However, there is limited data to describe the point prevalence of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa at a regional level. Understanding the epidemiology of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients and the quality of antibiotic prescribing is important to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions to promote rational use of antibiotics and improve clinical outcomes among patients. The objective of this study is to evaluate the prevalence of antibiotic prescribing among hospitalized patients, the prevalence of antibiotic use in different hospital ward/unit, and the quality indicators of antibiotic prescriptions in healthcare facilities across Africa.

Methods

Study Design

This systematic review of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement 2020 [23].

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

-

1.

Point prevalence studies conducted among hospitalized patients in acute care settings in Africa

-

2.

Studies published between January 2010 and 3 November 2022. The review was limited to studies published from January 2010 in order to provide estimates of the outcomes based on recent studies. In addition, most point prevalence surveys conducted among hospitalized patients in Africa were published from 2010 onwards.

-

3.

Studies conducted in all age groups and all inpatient settings

-

4.

Studies that were published in English language and available as free full text

Exclusion Criteria

-

1.

Longitudinal studies that accessed antibiotic use among hospitalized patients

-

2.

Point prevalence studies that evaluated antibiotic use in outpatient settings. This is because the current review was focused on antibiotic use among hospitalized patients only.

-

3.

Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in a specific patient population such as COVID-19 patients only was excluded.

-

4.

Studies that described antibiotic consumption in defined daily doses without the rate of antibiotic use

-

5.

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses, editorials, letters to editors, commentaries, and unpublished articles of antibiotic use

Information Sources

Three electronic databases including PubMed, Scopus, and African Journals Online (AJOL) were searched to identify eligible articles. The search was conducted using the search terms described under search strategy. Google Scholar search was also conducted to find eligible articles. Additional search was conducted by checking the reference lists of selected articles.

Search Strategy

The search terms used include “point-prevalence study,” “antibiotic use,” and “Africa” along with their synonyms. The terms were combined using Boolean operators. The search terms used for the electronic search are as follows: Antibiotic use OR Antibiotic prescribing OR Antimicrobial use OR antimicrobial prescribing AND hospitalized patients OR acute care patients AND Africa AND point prevalence survey OR point-prevalence study.

Selection Process

The results of the electronic search were combined and checked for the removal of duplicate articles. Screening of the titles and abstracts of non-duplicate articles was conducted to identify potentially eligible articles. Ineligible articles at this stage were excluded. The full text of the articles that fulfilled eligibility criteria were assessed for final selection and for data collection.

Data Collection Process

The selected articles were assessed for quality and reviewed for data collection using a predesigned form. Data was extracted by one independent reviewer (UA), and the extracted information was checked by the second reviewer. Consensus was used to address any disagreements between the reviewers.

Data Items

The data items collected from the selected articles include first author’s name and year of publication, country, study setting/number of center(s), study design, study duration, number of patients involved, PPS protocol used (ECDC, CDC, or as defined by the authors), overall prevalence of antibiotic use, prevalence of antibiotic use in different wards, indications for antibiotic use, types of antibiotic, and quality indicators such as duration of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis, redundant antibiotic use, and documentation of reason for antibiotic use.

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment for the selected articles was performed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) [24]. The NOS consists of three sections including selection, comparability, and outcomes. Quality assessment was conducted by an independent reviewer (MS), and the result was randomly checked by a second reviewer (UA). Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through consensus.

Results

Study Selection

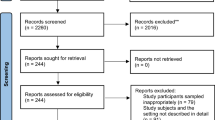

The search conducted on PubMed, Scopus, and African Journal Online databases yielded 6761, 306, and 91 articles, respectively. A total of 96 articles were identified after screening the first 1000 results from Google Scholar. Overall, 7254 articles were retrieved from the databases after the search. Of the 7254 articles, 22 duplicate articles were identified and removed. The title and abstract of the remaining articles were screened to remove articles that were not relevant to this systematic review and meta-analysis. The full text of 60 articles was assessed for inclusion based on the eligibility criteria, and 28 articles from 28 studies were selected. Figure 1 illustrates the procedure used during the screening and selection process.

Characteristics of Selected Studies

Most of the selected studies were from Nigeria (n = 9), Ghana (n = 6), Kenya (n = 4), Tanzania (n = 2), and South Africa (n = 2). Most of the studies (n = 17) involved multiple centers and 9 and 2 studies conducted in single and two centers, respectively. Majority of the studies were conducted before COVID-19 pandemic with 10 studies conducted in 2019 and four each in 2016 and 2017. There were two studies conducted in 2021 and one study in 2020. The number of patients involved in the selected studies ranged from 113 to 4407 patients. Most studies (n = 24) included patients from different wards while two studies each involved only surgical and pediatric population. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the selected studies.

Quality Assessment of Selected Studies

Almost all the studies included a population that is either truly or somewhat representative of the target population. Similarly, almost all the included studies had a sample size that is satisfactory and justified. The quality score among the included studies ranged from 4 to 9 with 23 studies (82.1%) scoring >7 points. Overall, 24 studies (85.7%) were found to have good quality while 3 studies had fair quality. One study was adjudged to have poor quality. Table 2 shows the quality assessment results of the studies included in this review.

Qualitative Summary of Results

Overall Prevalence and Prevalence of Antibiotic Use in Different Wards/Units Among Hospitalized Patients in Africa

Overall, the prevalence of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa ranged from 27.6 to 83.5% [28, 39]. The prevalence of antibiotic use was higher in West Africa (ranged from 51.4 to 83.5%) [19, 21, 22, 25,26,27, 29, 33, 35,36,37, 39,40,41, 47, 48], followed by North Africa (79.1%) [20], East Africa (ranged from 27.6 to 73.7%) [28, 30,31,32, 34, 38, 42,43,44], and South Africa (ranged from 33.6 to 49.7%) [45, 46]. The highest prevalence of antibiotic use was found in Nigeria (83.5%) [39], Ghana (82%) [25], Egypt (79.1%) [20], and Uganda (73.7%) [34]. The lowest rate of antibiotic use was observed in Malawi (27.6%) [28], followed by South Africa (33.6%) [45] and Tanzania (44.0%) [31]. Table 1 summarizes the prevalence and types of HAIs reported in the selected studies. The prevalence of antibiotic use was higher among patients admitted to the ICU (64.4–100%; n = 9 studies) [30, 32, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 47], followed by pediatric medical (10.6–94.6%; n = 13 studies) [21, 22, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 47, 48], neonatal (45.5–93.7%; n = 7 studies) [22, 32, 36, 38, 40, 42, 47], pediatric surgery (56.7–90.7%; n = 6 studies) [22, 30, 35, 36, 40, 47], and adult surgical (22.9–82.9%, n = 12 studies) [21, 22, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 47] ward. The rate of antibiotic use among patients hospitalized on other wards includes neonatal ICU (53.1–76.8%; n = 3 studies) [30, 36, 40], adult medical (19.5–73.6%; n = 13 studies) [21, 22, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 47, 48], and OBG/postnatal (6.7–92.5%; n = 8 studies) [21, 22, 30, 32, 35, 38, 42, 43] wards.

Indication for Antibiotic Use and the Routes of Administration

The indications for antibiotic use among hospitalized patients varied between the studies. Community-acquired infections were the most common indication for antibiotic use and ranged from 27.7 to 61.0% (n = 19 studies) [19,20,21,22, 27, 30,31,32,33,34,35, 38,39,40,41,42, 44, 47], followed by surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis (14.6–45.3%; n = 17 studies) [19,20,21,22, 27, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 47]. Hospital-acquired infections (1.2–40.3%; n = 19 studies) [19,20,21,22, 27, 30,31,32,33,34,35, 38,39,40,41,42, 44, 47] and medical prophylaxis (0.5–29.1%; n = 17 studies) [19,20,21,22, 27, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 47] were the other indications for antibiotic use in African settings. Both oral and parenteral antibiotics are used among hospitalized patients in Africa. The parenteral antibiotics were the most commonly used and accounted for 54.0–98.6% of all antibiotics (n = 18 studies) [19,20,21,22, 30, 32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41, 42, 45,46,47,48] while oral antibiotics accounted for 11.0–46.0% (n = 11 studies) [19, 21, 22, 32, 34, 37, 39, 42, 45,46,47].

Antibiotic Used Among Hospitalized Patients

A total of 15 studies reported top five most commonly prescribed antibiotics in inpatient settings in Africa. Based on the results, ceftriaxone (n = 14 studies) and metronidazole (n = 12 studies) were the most commonly used antibiotics, and the rates ranged from 7.4 to 51.7% [19, 21, 22, 27, 28, 31, 33,34,35,36, 38, 39, 41, 44, 46] and 14.6 to 44.8% [19, 21, 22, 28, 31, 33,34,35,36, 38, 39, 41, 44], respectively. This was followed by gentamicin (n = 8 studies; range: 6.6–22.3%) [19, 21, 22, 27, 31, 33, 34, 38, 44, 46], ampicillin (n = 6 studies; range: 6.0–29.2%) [27, 29, 31, 34, 44, 46], cefuroxime (n = 6 studies; range: 5.4–18.4%) [21, 27, 35, 36, 39, 41], ciprofloxacin (n = 6 studies; range: 7.8–17.4%) [21, 22, 27, 28, 33, 36], and amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 6 studies; range: 8.8–13.4%) [22, 33, 35, 36, 41, 46]. Other antibiotic used include ampicillin-cloxacillin combination (n = 3 studies; range: 6–17.0%) [31, 33, 34, 44] and amoxicillin (n = 3 studies; range: 24.1–36.5%) [27,28,29]. Overall, only seven studies described antibiotics used based on the access, watch, and reserve (AWaRe) classification. The access group was the most commonly used antibiotics and ranged between 46.3 and 97.9% [20, 21, 32, 34, 45, 46], while the watch and reserve group accounted for 1.8–53.5% [20, 21, 32, 34, 45, 46] and 0.0–5.0% [20, 21, 32, 34, 45, 46], respectively.

Quality Indicators for Antibiotic Prescribing Among Hospitalized Patients

Eight studies describe the documentation of the reasons for antibiotic prescribing in patient notes [20, 27, 33, 34, 36, 38,39,40]. The results indicated that the rate of documentation ranged between 37.3 and 100%. The documentation of dates for stop/review ranged from 19.6 to 100% (n = 5 studies) [20, 33, 36, 39, 40] while taking specimen for microbiology culture ranged between 2.7 and 25% (n = 3 studies) [19, 20, 27]. The quality of antibiotic prescribing varied with the prevalence of prolonged surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis (administration for more than 24 h) ranging from 66.7 to 100% (n = 14 studies) [19,20,21,22, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 39,40,41, 45, 46]. One study reported that 6.2% of hospitalized patients with two or more antibiotics had redundant antibiotic prescriptions [22]. Table 3 shows the quality indicators of antibiotic prescribed among hospitalized patients.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the prevalence, indication, and types of antibiotics used among hospitalized patients in Africa, as well as the quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing. The study found that there are limited studies that reported the prevalence of antibiotics used among hospitalized patients, particularly in the central and North African regions, where there was paucity of studies. The studies used different protocols including the World Health Organization protocol, global point prevalence survey protocol, and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control protocol to conduct the studies reflecting absence of an African protocol for conducting point prevalence of antibiotic use in African hospitals. Most of the included studies included were found to have good quality. The results showed that the prevalence of antibiotic use in inpatient settings in Africa is higher than the prevalence reported in Europe (30.5%) [17] and the USA (49.9%) [18]. This could be explained by the lack of adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines among prescribers [49, 50], inadequate knowledge of antibiotic prescribing among prescribers, and the misuse of antibiotics for the management of viral infections [51, 52]. The high rate of antibiotics used in inpatient settings in Africa highlights the need for antimicrobial stewardship program to promote rational use of antibiotics. ICU had the highest prevalence of antibiotic use, similar to the finding of the global point prevalence survey of 53 countries [53]. This was followed by pediatric medical, neonatal, and pediatric and adult surgical wards. This finding indicates the inpatient wards that should be prioritized for the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship program.

The current study also found that the most common indication for antibiotic use among inpatients in Africa was community-acquired infections. This is consistent with the finding in Europe [17], the USA [18], and the global PPS of antimicrobial use [53]. This result indicates the need to promote infection control and prevention strategies among the public to reduce the burden of community-acquired infections and eventually reduce the use of antibiotics. Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis was the second most common indication for antibiotic use in African inpatient settings. This is not in agreement with the result of the global PPS where hospital-acquired infection is the second most common indication. It is important to note that about two-thirds to 100% of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis was prolonged beyond 24 h. In a similar study, more than half of the surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis prescriptions were prolonged beyond 24 h [17]. Excessive use of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis contributes the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance. This result confirms the findings of previous studies that have demonstrated excessive use of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis [22, 54]. Prolonged use of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis is attributed to lack of knowledge among prescribers [55] and the use of antibiotics to augment suboptimal infection control and prevention practices. Therefore, surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis represents an important priority for the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship program in Africa. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship in improving the use of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis and improving patient outcomes [12]. The results also showed that a considerable amount of antibiotics are used for hospital-acquired infections. High rate of hospital-acquired infections is attributed to poor infection control and prevention practices due to lack of training, lack of infrastructure, and high workload among healthcare workers in Africa [56, 57]. Therefore, infection prevention and control strategies including training of healthcare workers and promoting hand hygiene practices are recommended to reduce the burden of healthcare-associated infections and subsequently reduce antibiotic use in inpatient settings.

Ceftriaxone, metronidazole, gentamicin, ampicillin, cefuroxime, and ciprofloxacin were the most common antibiotics used among hospitalized patients in Africa. This was not consistent with the finding in Europe where beta-lactam plus beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations including amoxicillin-clavulanate and piperacillin-tazobactam; third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones were the most common antibiotics used in acute care hospitals [17]. In China, third-generation cephalosporin, fluoroquinolones, and metronidazole were the most common antibiotics used among hospitalized patients [58]. These variations are attributed to the differences in the burden of infectious diseases and the difference in antibiotic resistance pattern between the countries. In addition, high rate of ceftriaxone, metronidazole, gentamicin, and ampicillin usage could be attributed to the fact that they are relatively cheaper and have better safety profile than the beta-lactam beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations and fluoroquinolones. The high rate of ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin usage in Africa is another important target for antimicrobial stewardship interventions. This is because these antibiotics are associated with increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection and the emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae.

Most of the antibiotics used in Africa are in the access group while a considerable percentage of antibiotics belong to the watch group. However, the access group accounts for less than 60% of the antibiotics in most of the studies while the watch group accounted for more than 40% of the antibiotics in most of the studies. A previous study revealed that low-income countries had the highest access (62.8%), lowest watch 36.0%), and no reserve antibiotic prescription among adults compared to the other income groups [59]. The results of the current study imply that the antibiotics in the watch group were overused and those in the access group were underused. Therefore, interventions to promote more usage of antibiotics in the access group are recommended. Antibiotics in the watch group have higher potential for antibiotic resistance compared to those in the access group [60]. In addition, antibiotics in the reserve group are used for the treatment of multidrug-resistant infections. The low usage of the reserve antibiotics in Africa may be attributed to the non-availability of the antibiotics [59], and in some cases, the expensive cost of these life-saving medications may limit their use for those who pay for health services out-of-pocket. Therefore, interventions that promote accessibility, affordability, and availability of reserve antibiotics are recommended.

The general principle of antibiotic use requires taking specimen for microbiology culture and sensitive to guide definitive antibiotic therapy and minimize the risk of antibiotic resistance. The current study found that only one-quarter of patients receiving antibiotic therapy had specimen taken for culture. This shows that there is a major gap in the management of infectious diseases in Africa and highlights the need to strengthen laboratory capacity through diagnostic stewardship. The documentation of the reason(s) for antibiotic prescription was observed in most of the cases, although there is still room for improvement. The results also revealed that less than one-third of patients receiving antibiotics in Africa had a review/stop date documented in their case notes. The implication of this finding is the tendency to use antibiotics inappropriately and excessively. There was also report of redundant antibiotic combinations among inpatients in African hospital. These findings highlight some important opportunities for hospital pharmacists across Africa to participate in antimicrobial stewardship program. Therefore, training of hospital pharmacists and pharmacy students on antimicrobial stewardship is recommended [11, 61, 62].

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant disruption in healthcare systems across the world, and Africa is no exemption. The pandemic has affected both antimicrobial stewardship and infection control and prevention programs across the globe. Available evidence has shown that the pandemic has increased the rate of multidrug-resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens [63]. There is paucity of data describing the impact of the pandemic on the prevalence and types of antibiotics prescribed among inpatients in Africa. Therefore, future studies should assess the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic prescribing among inpatients in Africa. This study has a number of limitations including selection bias due to scarcity of point prevalence studies from Central African and North African regions. In addition, the exclusion of studies published in languages other than English language may have excluded relevant articles. Therefore, the findings may not be easily generalizable to the entire continent. Secondly, there was heterogeneity in the reporting of the prevalence as only a few studies reported the 95% confidence interval. This made it difficult to perform a quantitative analysis of the results. Therefore, a standardized protocol for conducting and reporting point prevalence survey of antibiotic use among inpatients in Africa is required to facilitate the performance of meta-analysis in the future. Despite these limitations, the current review provide some insights into the prevalence, indications, and types of antibiotics used among hospitalized patients in Africa as well as the quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing.

Conclusion

The prevalence of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in Africa is relatively high compared to Europe and the USA. The prevalence of antibiotic use was higher in adult intensive care unit and pediatric medical and neonatal wards compared to other wards. Antibiotics were most commonly used for community-acquired infections, followed by surgical antibiotic prophylaxis where more than two-thirds of the prescriptions was prolonged beyond 24 h. Broad spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, gentamicin, and fluoroquinolones were among the most common antibiotics prescribed among inpatients in Africa. Antimicrobial stewardship interventions are recommended, particularly in the surgical, ICU, and pediatric wards, to improve quality use of antibiotics in African hospitals and prevent antibiotic resistance.

References

Knight GM, Glover RE, McQuaid CF, Olaru ID, Gallandat K, Leclerc QJ, Fuller NM, Willcocks SJ, Hasan R, van Kleef E, Chandler CI. Antimicrobial resistance and COVID-19: intersections and implications. Elife. 2021;10:e64139.

Ansari S, Hays JP, Kemp A, Okechukwu R, Murugaiyan J, Ekwanzala MD, Ruiz Alvarez MJ, Paul-Satyaseela M, Iwu CD, Balleste-Delpierre C, Septimus E. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global antimicrobial and biocide resistance: an AMR Insights global perspective. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(2):dlab038.

Maragakis LL, Perencevich EN, Cosgrove SE. Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2008;6(5):751–63.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019.

Abubakar U, Tangiisuran B, Elnaem MH, Sulaiman SA, Khan FU. Mortality and its predictors among hospitalized patients with infections due to extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) Enterobacteriaceae in Malaysia: a retrospective observational study. Future J Pharm Sci. 2022;8(1):1–8.

Abubakar U, Zulkarnain AI, Rodríguez-Baño J, Kamarudin N, Elrggal ME, Elnaem MH, Harun SN. Treatments and predictors of mortality for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli infections in Malaysia: a retrospective cohort study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(12):415.

Abubakar U, Sulaiman SA. Prevalence, trend and antimicrobial susceptibility of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Nigeria: a systematic review. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(6):763–70.

O'Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations.

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization; 2014.

CDC A. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019.

Abubakar U, Tangiisuran B. Nationwide survey of pharmacists’ involvement in antimicrobial stewardship programs in Nigerian tertiary hospitals. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:148–53.

Abubakar U, Syed Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Impact of pharmacist-led antibiotic stewardship interventions on compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in obstetric and gynecologic surgeries in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213395.

Kaki R, Elligsen M, Walker S, Simor A, Palmay L, Daneman N. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship in critical care: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(6):1223–30.

Huebner C, Flessa S, Huebner NO. The economic impact of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals: a systematic literature review. J Hosp Infect. 2019;102(4):369–76.

Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, Sharland M, Goossens H, ARPEC Project Group, Calle GM, Garrahan JP, Clark J, Cooper C, Blyth CC. The worldwide Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(4):1106–17.

Ustun C, Hosoglu S, Geyik MF, Parlak Z, Ayaz C. The accuracy and validity of a weekly point-prevalence survey for evaluating the trend of hospital-acquired infections in a university hospital in Turkey. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(10):e684–7.

Plachouras D, Kärki T, Hansen S, Hopkins S, Lyytikäinen O, Moro ML, Reilly J, Zarb P, Zingg W, Kinross P, Weist K. Antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals: results from the second point prevalence survey (PPS) of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2016 to 2017. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23(46):1800393.

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM. Emerging infections program healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use prevalence survey team. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–208.

Bediako-Bowan AA, Owusu E, Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Sunkwa-Mills G, Bjerrum S, Opintan JA, Bannerman C, Mølbak K, Kurtzhals JA, Newman MJ. Antibiotic use in surgical units of selected hospitals in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1.

Ashour RH, Abdelkader EA, Hamdy O, Elmetwally M, Laimon W, Abd-Elaziz MA. The pattern of antimicrobial prescription at a tertiary health center in Egypt: a point survey and implications. Infect Drug Resist. 2022:6365–78.

Aboderin AO, Adeyemo AT, Olayinka AA, Oginni AS, Adeyemo AT, Oni AA, Olabisi OF, Fayomi OD, Anuforo AC, Egwuenu A, Hamzat O. Antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients: a multi-center, point prevalence survey across public healthcare facilities, Osun State, Nigeria. Germs. 2021;11(4):523.

Abubakar U. Antibiotic use among hospitalized patients in northern Nigeria: a multicenter point-prevalence survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. 2021:372.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

Afriyie DK, Sefah IA, Sneddon J, Malcolm W, McKinney R, Cooper L, Kurdi A, Godman B, Seaton RA. Antimicrobial point prevalence surveys in two Ghanaian hospitals: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2(1):dlaa001.

Ahoyo TA, Bankolé HS, Adéoti FM, Gbohoun AA, Assavèdo S, Amoussou-Guénou M, Kindé-Gazard DA, Pittet D. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and anti-infective therapy in Benin: results of the first nationwide survey in 2012. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(1):1–6.

Amponsah OK, Buabeng KO, Owusu-Ofori A, Ayisi-Boateng NK, Hämeen-Anttila K, Enlund H. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic consumption across three hospitals in Ghana. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(1):dlab008.

Bunduki GK, Feasey N, Henrion MY, Noah P, Musaya J. Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in surgical wards of a large urban central hospital in Blantyre, Malawi: a point prevalence survey. Infect Prev Prac. 2021;3(3):100163.

Nsofor CA, Amadi ES, Ukwandu N. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in major hospitals in Owerri, Nigeria. EC Microbiol. 2016;3.5:522–7.

Fentie AM, Degefaw Y, Asfaw G, Shewarega W, Woldearegay M, Abebe E, Gebretekle GB. Multicentre point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use and healthcare-associated infections in Ethiopian hospitals. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e054541.

Horumpende PG, Mshana SE, Mouw EF, Mmbaga BT, Chilongola JO, de Mast Q. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use in three hospitals in North-Eastern Tanzania. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–6.

Kamita M, Maina M, Kimani R, Mwangi R, Mureithi D, Nduta C, Gitaka J. Point prevalence survey to assess antibiotic prescribing pattern among hospitalized patients in a county referral hospital in Kenya. Front Antibiot. 2022;1:993271.

Fowotade A, Fasuyi T, Aigbovo O, Versporten A, Adekanmbi O, Akinyemi O, Goossens H, Kehinde A, Oduyebo O. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescribing in a Nigerian hospital: findings and implications on antimicrobial resistance. West Afr J Med. 2020;37(3):216–20.

Kiggundu R, Wittenauer R, Waswa JP, Nakambale HN, Kitutu FE, Murungi M, Okuna N, Morries S, Lawry LL, Joshi MP, Stergachis A. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use across 13 hospitals in Uganda. Antibiotics. 2022;11(2):199.

Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Nartey ET, Bjerrum S, Adu-Aryee NA, Ofori-Adjei YA, Yawson AE, Newman MJ. Antibiotic use in a tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana: a point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):1–9.

Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Dayie NT, Egyir B, Sampane-Donkor E, Newman MJ, Opintan JA. Antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients: a multicentre point prevalence survey across seven hospitals in Ghana. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(3):dlab087.

Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Sunkwa-Mills G, Bediako-Bowan A, Akufo C, Bjerrum S, Owusu E, Enweronu-Laryea C, Opintan JA, Kurtzhals JA, Newman MJ. Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric inpatients in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Momanyi L, Opanga S, Nyamu D, Oluka M, Kurdi A, Godman B. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a leading referral hospital in Kenya: a point prevalence survey. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8(3):149.

Nnadozie UU, Umeokonkwo CD, Maduba CC, Onah II, Igwe-Okomiso D, Ogbonnaya IS, Onah CK, Okoye PC, Versporten A, Goossens H. Patterns of antimicrobial use in a specialized surgical hospital in Southeast Nigeria: need for a standardized protocol of antimicrobial use in the tropics. Niger J Med. 2021;30(2):187–91.

Oduyebo OO, Olayinka AT, Iregbu KC, Versporten A, Goossens H, Nwajiobi-Princewill PI, Jimoh O, Ige TO, Aigbe AI, Ola-Bello OI, Aboderin AO. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescribing in four Nigerian tertiary hospitals. Ann Trop Pathol. 2017;8(1):42.

Ogunleye OO, Oyawole MR, Odunuga PT, Kalejaye F, Yinka-Ogunleye AF, Olalekan A, Ogundele SO, Ebruke BE, Kalada Richard A, Anand Paramadhas BD, Kurdi A. A multicentre point prevalence study of antibiotics utilization in hospitalized patients in an urban secondary and a tertiary healthcare facilities in Nigeria: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2022;20(2):297–306.

Okoth C, Opanga S, Okalebo F, Oluka M, Baker Kurdi A, Godman B. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use and resistance at a referral hospital in Kenya: findings and implications. Hosp Pract. 2018;46(3):128–36.

Omulo S, Oluka M, Achieng L, Osoro E, Kinuthia R, Guantai A, Opanga SA, Ongayo M, Ndegwa L, Verani JR, Wesangula E. Point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use at three public referral hospitals in Kenya. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0270048.

Seni J, Mapunjo SG, Wittenauer R, Valimba R, Stergachis A, Werth BJ, Saitoti S, Mhadu NH, Lusaya E, Konduri N. Antimicrobial use across six referral hospitals in Tanzania: a point prevalence survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042819.

Skosana PP, Schellack N, Godman B, Kurdi A, Bennie M, Kruger D, Meyer JC. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2021;19(10):1353–66.

Skosana PP, Schellack N, Godman B, Kurdi A, Bennie M, Kruger D, Meyer JC. A national, multicentre, web-based point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use and quality indices among hospitalised paediatric patients across South Africa. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021.

Umeokonkwo CD, Madubueze UC, Onah CK, Okedo-Alex IN, Adeke AS, Versporten A, Goossens H, Igwe-Okomiso D, Okeke K, Azuogu BN, Onoh R. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescription in a tertiary hospital in South East Nigeria: a call for improved antibiotic stewardship. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:291–5.

Manga MM, Ibrahim M, Hassan UM, Joseph RH, Muhammad AS, Danimo MA, Ganiyu O, Versporten A, Oduyebo OO. Empirical antibiotherapy as a potential driver of antibiotic resistance: observations from a point prevalence survey of antibiotic consumption and resistance in Gombe, Nigeria. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2021;22(2):273–8.

Gasson J, Blockman M, Willems B. Antibiotic prescribing practice and adherence to guidelines in primary care in the Cape Town Metro District, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(4):304–10.

Obakiro SB, Napyo A, Wilberforce MJ, Adongo P, Kiyimba K, Anthierens S, Kostyanev T, Waako P, Van Royen P. Are antibiotic prescription practices in Eastern Uganda concordant with the national standard treatment guidelines? A cross-sectional retrospective study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2022;29:513–9.

Md Rezal RS, Hassali MA, Alrasheedy AA, Saleem F, Md Yusof FA, Godman B. Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions and behaviour towards antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2015;13(5):665–80.

Chukwu EE, Oladele DA, Enwuru CA, Gogwan PL, Abuh D, Audu RA, Ogunsola FT. Antimicrobial resistance awareness and antibiotic prescribing behavior among healthcare workers in Nigeria: a national survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1–2.

Versporten A, Zarb P, Caniaux I, Gros MF, Drapier N, Miller M, Jarlier V, Nathwani D, Goossens H, Koraqi A, Hoxha I. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(6):e619–29.

Abubakar U, Syed Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Utilization of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for obstetrics and gynaecology surgeries in Northern Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(5):1037–43.

Abubakar U, Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Knowledge and perception regarding surgical antibiotic prophylaxis among physicians in the department of obstetrics and gynecology. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;37(1):108–13.

Abubakar U, Amir O, Rodríguez-Baño J. Healthcare-associated infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of point prevalence studies. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2022;15(1):1–6.

Abubakar U. Point-prevalence survey of hospital acquired infections in three acute care hospitals in Northern Nigeria. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–7.

Xie DS, Xiang LL, Li R, Hu Q, Luo QQ, Xiong W. A multicenter point-prevalence survey of antibiotic use in 13 Chinese hospitals. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(1):55–61.

Pauwels I, Versporten A, Drapier N, Vlieghe E, Goossens H. Hospital antibiotic prescribing patterns in adult patients according to the WHO Access, Watch and Reserve classification (AWaRe): results from a worldwide point prevalence survey in 69 countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(6):1614–24.

World Health Organization. WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016-2018 early implementation.

Abubakar U, Sha’aban A, Mohammed M, Muhammad HT, Sulaiman SA, Amir O. Knowledge and self-reported confidence in antimicrobial stewardship programme among final year pharmacy undergraduate students in Malaysia and Nigeria. Pharm Educ. 2021;21:298–305.

Abubakar U, Muhammad HT, Sulaiman SA, Ramatillah DL, Amir O. Knowledge and self-confidence of antibiotic resistance, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and antibiotic stewardship among pharmacy undergraduate students in three Asian countries. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2020;12(3):265–73.

Abubakar U, Al-Anazi M, Alanazi Z, Rodríguez-Baño J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on multidrug resistant Gram positive and Gram negative pathogens: a systematic review. J Infect Public Health. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2022.12.022.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Usman Abubakar and Muhammad Salman. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Usman Abubakar, and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abubakar, U., Salman, M. Antibiotic Use Among Hospitalized Patients in Africa: A Systematic Review of Point Prevalence Studies. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 1308–1329 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01610-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01610-9