Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically impacted the world lifestyle. Epidemics are well-known to cause mental distress, and patients with a current or past history of obesity are at increased risk for the common presence of psychological comorbidities. This study investigates the psychological impact of the current pandemic in patients participating in a bariatric surgery program.

Methods

Patients were consecutively enrolled during the Italian lockdown among those waiting for bariatric surgery or attending a post-bariatric follow-up, and were asked to complete through an online platform the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 and a self-assessment questionnaire of 22 items evaluating the resilience, change in eating behavior and emotional responses referring to the ongoing pandemic.

Results

59% of the 434 enrolled subjects reported of being worried about the pandemic, and 63% specifically reported of being worried about their or their relatives’ health. 37% and 56% felt lonelier and more bored, respectively. 66% was hungrier with increased frequency of snacking (55%) and 39% reported more impulse to eat. Noteworthy, 49% felt unable to follow a recommended diet. No difference in terms of psychological profile was recorded among pre and post-bariatric subjects. Logistic regression analysis on post-bariatric patients showed a relationship between snacking, hunger, eating impulsivity, and anxiety, stress, and/or depression symptoms.

Conclusion

The pandemic led to increased psychological distress in patients with a current or past history of obesity, reducing quality of life and affecting dietary compliance. Targeted psychological support is warranted in times of increased stress for fragile subjects such as pre- and post-bariatric patients.

Level of evidence

Level V: cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11th 2020 [1]. Italy was the first country to be severely impacted by the virus spread in Europe and was in national quarantine starting on March 9th until May 4th, with all movements to be work-related or certified emergencies, and schools and most commercial services forced to shut down.

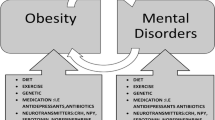

The profound and broad spectrum of psychological implications that epidemics can cause on the individual as a whole is well-established. Previous studies showed that mental disorders may vary from depression, anxiety, panic attacks, somatic symptoms, and symptoms that characterize post-traumatic stress disorder, to delirium, psychosis and even suicide [2, 3]. Regardless of exposure to infection, individuals may experience fear and anxiety of getting sick or dying and may also feel helpless or guilty towards those who have been infected [4]. Furthermore, it has been shown that, a month after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003, approximately 35% of people revealed moderate to severe depressive or anxiety symptoms [5] and, one year after, up to 64% of patients showed high levels of suffering, which were indicative of psychiatric morbidity [6]. Recent studies in mainland China during the current COVID-19 pandemic have shown that 54% of interviewees reported high levels of psychological distress with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression resulting from self-isolation and quarantine [7, 8].

In this context, subjects suffering from obesity represent a highly fragile population since this condition is often associated with significant psychological comorbidity [9], which can further aggravate following a highly traumatic event, causing discontinuous adherence to long-term treatment on top of other obvious psychological repercussions. Among subjects suffering from obesity who request bariatric surgery, in particular, there is a high prevalence of mood disorders, anxiety disorders and eating disorders [10,11,12]. In relation to the mechanisms of psychic functioning, it also emerges that patients suffering from obesity present cognitive, emotional and behavioral patterns characterized by impulsive traits and difficulties in self-regulating emotional states [13, 14]. It should be highlighted that psychological frailty can persist even after surgery: in fact, even if the severity of problematic eating behavior decreases immediately after the bariatric surgery, it tends to increase significantly between the first and third post-operative year [15]. Noteworthy, the prevalence of obesity in Italy is over 10% and rapidly increasing, making the number of patients possibly deriving significant stress and difficulty in adhering to treatment from the current pandemic not to be neglected [16].

Aim

The study aimed at identifying the emotional and relational impact that the COVID-19 health emergency and lockdown had on patients included in a bariatric surgery program, paying particular attention to the difference between patients waiting for surgery and those who had already undergone it. In particular, the elements of psychological frailty, the resources of resilience and the change in eating habits related to the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed.

Methods

Design

A nationwide survey aimed at subjects included in a bariatric surgery program was carried out in Italy during the generalized lockdown. Patients were enrolled through social media according to a consecutive eligibility criterion. In the period from the 6th of April to the 3rd of May 2020 patients who were candidates for a bariatric surgery procedure following a specific consultation or those who had already undergone the intervention were asked to answer a series of questionnaires through an online platform. Exclusion criteria were as follows: impaired ability to provide informed consent or understand or respond to questions due to intellectual impairment or limited Italian language knowledge; age below 18 years old; lack of consent. An anonymous participation and the confidentiality of the information collected were ensured.

The ethics committee of the University Hospital Campus Biomedico of Rome approved this study and its development. All the procedures performed in the study complied with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Measures

The current study involved the administration of a structured interview and a validated self-report questionnaire listed below for the evaluation of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 emergency and lockdown on the enrolled subjects. Patients were evaluated once through an online platform.

-

− A self-assessment interview consisting of personal data and 22 items evaluating the presence of psychological protective and risk factors with respect to the possibility of developing psychological distress. In particular, ability to resilience, change in eating behavior, and the emotional responses to their experience of the pandemic were recorded. The replies “often” and “very often” were grouped to obtain the percentage of patients giving a positive answer to each question (Supplementary Table 1).

-

− Depression anxiety stress scales DASS-21 [17], a validated instrument of 21 items that provides a general assessment of the psychological distress and three specific domains: depression, anxiety and stress perceptions, with high scale scores indicating high distress.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), v.20, was used for statistical analysis. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number and percentage. Normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The primary endpoint was to explore the DASS derived condition of depression, anxiety and stress in the post-operative bariatric population during the COVID-19 emergency in Italy. The secondary outcome was to explore the relationship between depression, anxiety, stress and fear of COVID-19 infection and eating behavior and lifestyle changes in the post-operative bariatric population. In addition, a subpopulation of subjects waiting for bariatric surgery was enrolled to explore whether there was a difference in the psychological response pattern in these subjects as opposed to those who had already undergone surgery. For continuous variables, a t student test to compare the distribution of the psychological parameters was conducted. Chi-square test/Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model was performed to analyze the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic (measured through a questionnaire whose scores were used as independent variable: emotionality domain, resilience domain and eating related) on DASS derived condition of depression, anxiety and stress used as the discrete dependent variable. Univariate analysis was performed by converting continuous variables into dummy dichotomic variables based on median values, while continuous variables were used for multivariate analysis. Multivariate Model: variables with significant univariate association (p value ≤ 0.05) as regressors. R2: the Nagelkerke's R2. Univariate and multivariate ordinal regression model was performed to analyze the effect of depression, anxiety, stress and fear of COVID-19 infection (used as exploratory variables) on eating behavior and lifestyle changes (used as discrete dependent variables). Three discrete and separately analyzed outcomes from the interview questionnaire were used as dependent variables: increased hunger; increased snacking, and increased impulsivity in eating. The univariate analysis was performed using dummy dichotomic variables based on the DASS threshold, which identify the condition of depression, anxiety and stress, while continuous variables were used for multivariate analysis. Multivariate Model: variables with significant univariate association (p value ≤ 0.05) as regressors. R2: the Nagelkerke's R2. The results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Population characteristics

Four hundred thirty-four patients with obesity were enrolled, and their general characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, 55 males (12.7%) and 379 females (87.3%) were enrolled, with an age between 21 and 67 years old, average 45.6 ± 9.62 years old. Among these, 375 (86.2%) had undergone bariatric surgery. Recorded marital status was as follows: 56 (13.6%) were unmarried, 311 (68.8%) were married, 57 (15.4%) were divorced and 10 (2.2%) were widowers. Thirteen subjects (3.4%) had completed primary school, 148 (35.1%) had a secondary junior school degree, 207 (47.4%) had a high school degree, 53 (11.3%) had a university degree; 13 (2.8%) had a Ph.D. Occupation was as follows: unemployed 50 (11.5%), employed 246 (54.8%), freelance 55 (14.1%), housewives 79 (18.8%) and students 4 (0.9%). Subjects who had undergone surgery had one of the following types: sleeve gastrectomy (n = 257, 69.5%), Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGBP) (n = 96, 25.1%), gastric banding (n = 22, 4.2%), Biliopancreatic diversion (n = 1, 0.1%) and Single anastomosis duodeno–ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADIS) (n = 4, 1.1%), Table 2. A stratification based on pre- and post-operative status showed that both populations presented similar general characteristics and exhibited only a significant difference in the marital status, the ones who had already undergone surgery showing a higher percentage of divorces (17.6% V.s. 1.3%, p = 0.008, Table 2).

Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population

The results obtained through the DASS questionnaire and that exploring emotions and eating behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, the study population reported to feel depressed in 26.1% of cases (n = 115), had significant anxiety in 24.7% of cases (n = 102), and was in psychological distress in 18.3% of cases (n = 82). Regarding the emotions domain during the COVID-19 pandemic, more than half of the subjects (57%) reported to be generally worried (often or very often). Specifically, most subjects reported of being worried about their or their relatives’ health (63%). 37% of subjects also described feeling lonelier and 56% reported an increased sense of boredom. In relation to the eating style domain, 66% of the sample reported feeling hungrier with increased frequency of snacking between meals (55%), while 39% of subjects reported a strong impulse to eat during the pandemic. Of note, 49% of the subjects declared that they felt unable to follow a recommended diet.

Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic based on pre or post-operative status

The results obtained through the DASS questionnaire and the COVID-19 related questionnaires based on the operative status of the patients are summarized in Table 3. According to the DASS questionnaire, subjects awaiting for bariatric surgery reported similar rates of depression (n = 16, 21.8% vs. n = 99, 28.8%, p = 0.875, Table 3), anxiety (n = 16, 23.5% vs. n = 86, 24.9%, p = 0.590, Table 3) and stress (n = 9, 12% vs. n = 73, 19.3%, p = 0.519, Table 3) compared to those who had already undergone it. The subjects also showed similar scores regarding depression, anxiety and stress (p = NS, Table 3), as well as the three domains derived from the COVID-19 related questionnaire: emotionality, resilience and eating behavior (p = NS, Table 3).

COVID-19 related psychological markers of depression, anxiety and stress in post-bariatric subjects

Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of COVID-19 related psychological markers of depression, anxiety and stress on post-bariatric subjects are summarized in Table 4.

Regarding the DASS derived depression status, the univariate analysis showed that the three domains from the COVID-19 questionnaire were all significant markers of depression: emotivity (OR 11.91; 95% CI 5.77–24.58; p = 0.0001, Table 4), resiliency (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.09–0.26; p = 0.0001, Table 4) and eating related domain (OR 6.92; 95% CI 3.75–12.76; p = 0.0001, Table 4). Being worried about COVID-19 also showed to be a marker of depression (OR 3.01; 95% CI 1.26–7.19; p = 0.0130, Table 4). A multivariate model using variables with significant univariate association as regressors showed that emotivity, (OR 1.327; 95% CI 1.225–1.437; p = 0.0001, Table 4), resiliency (OR 0.844, 95% CI 0.771–0.925; p = 0.0001, Table 4), and eating behavior (OR 1.073, 95% CI 1.00–1.152; p = 0.049, Table 4) remained significant markers of depression, and this model explained 52% of the variance of depression (R2 = 0.525; p = 0.0001, Table 4).

Regarding the DASS derived anxiety status, the univariate analysis showed that the three domains from the COVID-19 questionnaire were all significant markers of anxiety: emotivity (OR 9.23; 95% CI 4.46–19.12; p = 0.0001, Table 4), resiliency (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.15–0.41; p = 0.0001, Table 4) and eating behavior (OR 5.32; 95% CI 2.87–9.87; p = 0.0001, Table 4). Being worried about COVID-19 also showed to be a marker of anxiety (OR 2.48; 95% CI 1.02–6.02; p = 0.0450, Table 4). A multivariate model built as previously explained showed that emotivity (OR 1.295; 95% CI 1.207–1.39; p = 0.0001, Table 4) and eating behavior (OR 1.069, 95% CI 1.009–1.132; p = 0.024, Table 4) remained significant markers of anxiety, with the model explaining 36.2% of the variance (R2 = 0.362; p = 0.0001, Table 4).

Regarding the DASS derived stress status, the univariate analysis showed that the three domains from the COVID-19 questionnaire were all significant markers of stress: emotivity (OR 24.93; 95% CI 7.68–80.93; p = 0.0001, Table 4), resiliency (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.09–0.30; p = 0.0001, Table 4) and eating behavior (OR 4.95; 95% CI 2.56–9.57; p = 0.0001, Table 4). Being worried about COVID-19 was not a marker of stress (p = NS, Table 4). A multivariate model built as previously explained showed that emotivity, (OR 1.38; 95% CI 1.26–1.52; p = 0.0001, Table 4) and resiliency (OR 0.812, 95% CI 0.742–0.888; p = 0.0001, Table 4) remained significant markers of stress, with the model explaining 53.6% of the variance (R2 = 0.536; p = 0.0001, Table 4).

DASS derived depression, anxiety and stress as markers of lifestyle and eating related behavioral characteristic during COVID-19 pandemic in post-bariatric subjects

Univariate and multivariate ordinal logistic regression analysis of depression, anxiety and stress as markers of lifestyle and eating related behavioral characteristic during COVID-19 pandemic in the bariatric operated population are summarized in Table 5.

Regarding the increased hunger, the univariate analysis showed that the three statuses from the DASS questionnaire were all significant markers of changes in the hunger domain: depression (B: 0.30; 95% CI 0.23–0.36; p = 0.0001, Table 5), anxiety (B: 0.25, 95% CI 0.18–0.33; p = 0.0001, Table 5), and stress (B: 0.21, 95% CI 0.16–0.26; p = 0.0001, Table 5). Being worried about COVID-19 was not a marker of increased hunger (p = NS, Table 5). A multivariate model built as previously explained showed that only anxiety (B: 0.25; 95% CI 0.15–4.85; p = 0.0001, Table 5), remained a significant marker of increased hunger and this model explained 23.1% of the variance of increased hunger (R2 = 0.231; p = 0.0001, Table 5).

Regarding the increased snacking, the univariate analysis showed that the three statuses from the DASS questionnaire were all significant markers of changes in the snacking domain: depression (B: 0.21; 95% CI 0.16–0,27; p = 0.0001, Table 5), anxiety (B: 0.19, 95% CI 0.12–0.26; p = 0.0001, Table 5), and stress (B: 0.18, 95% CI 0.13–0.23; p = 0.0001, Table 5). Being worried about COVID-19 was not a marker of increased snacking (p = NS, Table 5). A multivariate built as previously explained showed that only depression (B: 0.14; 95% CI 0.05–0.23; p = 0.002, Table 5), remained a significant marker of increased snacking, with the model explaining 15% of the variance of increased snacking (R2 = 0.15; p = 0.0001, Table 5).

Regarding the increased impulsivity in eating, the univariate analysis showed that the three statuses from the DASS questionnaire were all significant markers of changes in the impulsivity in eating domain: depression (B: 0.24; 95% CI 0.18–0.30; p = 0.0001, Table 5), anxiety (B: 0.22, 95% CI 0.15–0.29; p = 0.0001, Table 5), and stress (B: 0.20, 95% CI 0.15–0.25; p = 0.0001, Table 5). Being worried about COVID-19 was not a marker of increased impulsivity in eating (p = NS, Table 5). A multivariate model built as previously explained showed that only depression (B: 0.14; 95% CI 0.05–0.23; p = 0.002, Table 5) and stress B: 0.099; 95% CI 0.02–1.18; p = 0.019, Table 5), remained significant markers of increased impulsivity in eating, with the model explaining 18% of the variance of increased impulsivity in eating (R2 = 0.18; p = 0.0001, Table 5).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically changed lifestyles and daily routines around the world. In particular, during the lockdown period, citizens were called to self-distancing measures, travel restrictions, limited access to services and family isolation to prevent the spread of the virus. In addition, many families have experienced significant financial difficulties resulting from precarious work and, in some cases, from job loss [18]. Moreover, early during the pandemic, many studies have reported an increased risk of developing severe complications following COVID-19 infection in patients with obesity [19,20,21,22]. The finding has been given wide attention by media, possibly contributing to worsen the sense of fear of those with a current or past history of weight excess.

In line with previous reports [23,24,25,26], the present study showed that more than half of the study population was generally very concerned about the current pandemic. The prevalent concerns focused mainly on the fear for one's own health and for that of family members. About one fourth of the subjects reported of feeling depressed, anxious or stressed. Moreover, recent research stresses that high levels of suffering related to COVID-19 can lead to emotional dysregulation resulting in maladaptive eating behaviors, such as binge eating, grazing and emotional eating both before and after bariatric surgery [27]. As previously pointed out, the state of alarm and reactive concern to the current pandemic situation enter a context of particularly fragile patients [28, 29], possibly impacting in particular on the ability to maintain a healthy lifestyle and proper eating behavior. In fact, the present study showed that during the lockdown period, the majority of the study population felt hungrier and increased the frequency of snacking. Many declared an uncontrollable urge to eat and, in general, that they felt unable to follow the prescribed diet. From the data obtained, it may be postulated that the difficulty of regulating a pre-existing eating misbehavior was further aggravated during the pandemic, and the increased sense of loneliness and boredom might have contributed to further increase the eating dysregulation. It is also possible that a feedback circle is created between anxiety, concern related to the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and maladaptive eating behavior.

Noteworthy, no significant difference between candidates to the intervention and those who had already undergone it were present regarding mental distress, eating disorder and resilience. We may therefore assume that the experience of anguish, stress and anxiety is a transversal element that impacts all people with a current or past history of obesity.

The conducted study highlights a prevalence of clinically significant mental distress that varies between 12 and 26% of symptoms of clinically significant anxiety, depression and stress. The obtained results show, in particular, a relationship between snacking, increased hunger, increased impulsivity in eating, and the presence of significant anxiety and/or depression symptoms. This picture can be interpreted in the light of previous reports showing that mental distress tends to significantly reduce the quality of life and inevitably has an impact on the compliance to dietary treatments [30]. Odom et al. [31] highlight, in particular, that the risk of weight regain in obese patients is closely linked to a worsening in the depressive state. Mc Guire et al. [32]confirm this fact, claiming that the severity of depression is an important risk factor for weight regain. In the present research, the variable resilience intended as a protective factor with respect to psychic discomfort was also considered. In literature, resilience expresses, in fact, the ability to maintain one’s orientation towards existential purposes, despite lasting adversities and stressful events. It foresees an attitude of perseverance in front of an obstacle and openness to change. This concept can therefore be understood as the ability to persistently face the difficulties encountered in the different areas of one's life, maintaining a good awareness of oneself and one's internal coherence [33]. As hypothesized and in line with what is expressed in the literature, we showed that the presence of resilience resources decreased the possibility of manifesting clinically significant depressive and stress symptoms in post-bariatric patients.

The strong connection between mental status and food behavior warrants first of all an accurately targeted psychological support in order to favor compliance to dietary treatments. However, some dietary manipulations including certain foods [34, 35], food supplements [36, 37], and dietary patterns [38,39,40,41,42,43] together with pharmacological treatment [44, 45] have been shown to impact appetite and mood and/or proved particularly beneficial in subjects with severe obesity and in post-bariatric patients. Such measures should be therefore taken into consideration in the next months in order to favor dietary adherence and metabolic improvement, leveraging a multidisciplinary approach to treat those severely obese seeking bariatric surgery and those who have lost weight but need lifelong follow-up after bariatric surgery [46].

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and a priori power was not calculated, given the exploratory nature of the study. The design of the study was cross-sectional, making causal correlation assessment not possible. Moreover, anthropometric parameters were not part of the questionnaires, and correction for such possible confounders was therefore not performed. Finally, no in person interview was performed, and psychological assessment solely relied on online administration of questionnaires. Moreover, the COVID-19 specific questionnaire has not been validated yet. However, to the best of our knowledge, no validated questionnaire is currently available in order to explore the domains of interest during a pandemic. Our study also features some strengths. First, the use of questionnaires should not only be viewed as a limitation. In fact, given the nationwide nature of the survey, if in-person psychological assessment were to be chosen, more than one mental health professional would have been involved, possibly accounting for bias. Therefore, the absence of personal interpretation obtained through the choice of questionnaire-driven evaluation has allowed for the absence of operator-dependent variability. Furthermore, patients all over the country replied to the audit, allowing for a generalized picture rather than that of a single region. This is particularly important as COVID-19 has differentially spread across regions, with the north being severely impacted and the south only partially affected.

In conclusion, our study shows that COVID-19 had a significant emotional impact on patients participating in a bariatric surgery program, inevitably affecting eating habits. According to the results, it seems that general concern related to COVID-19, isolation and social distancing, the fear of contagion for oneself and for others may activate depressive states and anxiety and inevitably require good resilience qualities stimulating a process of functional adaptation to one's well-being. Accurately targeted psychological support is warranted in times of increased stress for more fragile subjects such as those with severe obesity or those who have undergone bariatric surgery in order to favor dietary and treatment compliance and prevent both psychological and organic complications.

What is already known on this subject?

The literature supports the broad psychological impact that pandemics over the years have had on the individual as a whole. Obesity identifies a particularly fragile population since the condition is often associated with significant psychiatric comorbidity. Therefore, a pandemic event may aggravate a pre-existing condition of mental discomfort, particularly affecting the patient's ability to maintain a healthy lifestyle and dietary behavior.

What your study adds?

The study shows that patients included in a bariatric surgery program are generally very worried about the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the fears mainly focus on their own health and that of family members regardless of whether they have undergone surgery. The difficulty in regulating eating behavior is further aggravated by the presence of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. However, resources of resilience represent a protective factor in preventing the development of discomfort.

References

Del Rio C, Malani PN (2020) COVID-19-new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3072

Müller N (2015) Infectious diseases and mental health. Key Issues Ment Health 179:14

Sim K, Huak Chan Y, Chong PN, Chua HC, Wen Soon S (2010) Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res 68(2):195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004

Tucci V, Moukaddam N, Meadows J, Shah S, Galwankar SC, Kapur GB (2017) The forgotten plague: psychiatric manifestations of Ebola, Zika, and emerging infectious diseases. J Glob Infect Dis 9(4):151–156. https://doi.org/10.4103/jgid.jgid_66_17

Cheng SK, Wong CW, Tsang J, Wong KC (2004) Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Psychol Med 34(7):1187–1195. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704002272

Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, Chu CM, Wong PC, Tsang KW, Chua SE (2007) Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry 52(4):233–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200405

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R (2004) SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 10(7):1206–1212. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1007.030703

Malik S, Mitchell JE, Engel S, Crosby R, Wonderlich S (2014) Psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates: a review of studies using structured diagnostic interviews. Compr Psychiatry 55(2):248–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.021

Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW (2003) Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 158(12):1139–1147. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg275

Yanovski SZ (2003) Binge eating disorder and obesity in 2003: could treating an eating disorder have a positive effect on the obesity epidemic? Int J Eat Disord 34(Suppl):S117–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10211

Sarwer DB, Allison KC, Wadden TA, Ashare R, Spitzer JC, McCuen-Wurst C, LaGrotte C, Williams NN, Edwards M, Tewksbury C, Wu J (2019) Psychopathology, disordered eating, and impulsivity as predictors of outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 15(4):650–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2019.01.029

Herpertz S, Kielmann R, Wolf AM, Hebebrand J, Senf W (2004) Do psychosocial variables predict weight loss or mental health after obesity surgery? A systematic review. Obes Res 12(10):1554–1569. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.195

Taube-Schiff M, Van Exan J, Tanaka R, Wnuk S, Hawa R, Sockalingam S (2015) Attachment style and emotional eating in bariatric surgery candidates: the mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation. Eat Behav 18:36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.011

Nasirzadeh Y, Kantarovich K, Wnuk S, Okrainec A, Cassin SE, Hawa R, Sockalingam S (2018) Binge eating, loss of control over eating, emotional eating, and night eating after bariatric surgery: results from the Toronto Bari-PSYCH Cohort Study. Obes Surg 28(7):2032–2039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3137-8

Watanabe M, Risi R, De Giorgi F, Tuccinardi D, Mariani S, Basciani S, Lubrano C, Lenzi A, Gnessi L (2020) Obesity treatment within the Italian national healthcare system tertiary care centers: what can we learn? Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00936-1

Bottesi G, Ghisi M, Altoe G, Conforti E, Melli G, Sica C (2015) The Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Compr Psychiatry 60:170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.04.005

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395(10227):912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S, Sterling S, Johnson D, Francois F, Stachel A (2020) Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa415

Watanabe M, Risi R, Tuccinardi D, Baquero CJ, Manfrini S, Gnessi L (2020) Obesity and SARS-CoV-2: a population to safeguard. Diabet Metab Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3325

Busetto L, Bettini S, Fabris R, Serra R, Dal Pra C, Maffei P, Rossato M, Fioretto P, Vettor R (2020) Obesity and COVID-19: an Italian snapshot. Obesity (Silver Spring). https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22918

Watanabe M, Caruso D, Tuccinardi D, Risi R, Zerunian M, Polici M, Pucciarelli F, Tarallo M, Strigari L, Manfrini S, Mariani S, Basciani S, Lubrano C, Laghi A, Gnessi L (2020) Visceral fat shows the strongest association with the need of intensive Care in Patients with COVID-19. Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154319

Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P (2004) Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 55(9):1055–1057. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055

Blendon RJ, Benson JM, DesRoches CM, Raleigh E, Taylor-Clark K (2004) The public's response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin Infect Dis 38(7):925–931. https://doi.org/10.1086/382355

Desclaux A, Badji D, Ndione AG, Sow K (2017) Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts' perceptions in Senegal. Soc Sci Med 178:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.009

Reynolds DL, Garay JR, Deamond SL, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R (2008) Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol Infect 136(7). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268807009156

Sockalingam S, Leung SE, Cassin SE (2020) The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Bariatric Surgery: Redefining Psychosocial Care. Obesity (Silver Spring) 28(6):1010–1012. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22836

Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, Courcoulas AP, Pilkonis PA, Ringham RM, Soulakova JN, Weissfeld LA, Rofey DL (2007) Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry 164(2):328–334. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.328(quiz 374)

Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA, Devlin MJ, Strain GW, Elder KA, Marcus MD, Wonderlich S, Christian NJ, Yanovski SZ (2012) Psychopathology before surgery in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery-3 (LABS-3) psychosocial study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 8(5):533–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.07.001

Unal S, Sevincer GM, Maner AF (2019) Prediction of weight regain after bariatric surgery by night eating, emotional eating, eating concerns, depression and demographic characteristics. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 30(1):31–41

Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, Miller WW, Hakmeh B, Zaremba DL, Altattan M, Balasubramaniam M, Gibbs DS, Krause KR, Chengelis DL, Franklin BA, McCullough PA (2010) Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 20(3):349–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-9895-6

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO (1999) What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol 67(2):177–185. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.177

Sisto A, Vicinanza F, Campanozzi LL, Ricci G, Tartaglini D, Tambone V (2019) Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: a literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110745

Tuccinardi D, Farr OM, Upadhyay J, Oussaada SM, Klapa MI, Candela M, Rampelli S, Lehoux S, Lazaro I, Sala-Vila A, Brigidi P, Cummings RD, Mantzoros CS (2019) Mechanisms underlying the cardiometabolic protective effect of walnut consumption in obese people: a cross-over, randomized, double-blind, controlled inpatient physiology study. Diabetes Obes Metab 21(9):2086–2095. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13773

Farr OM, Tuccinardi D, Upadhyay J, Oussaada SM, Mantzoros CS (2018) Walnut consumption increases activation of the insula to highly desirable food cues: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over fMRI study. Diabetes Obes Metab 20(1):173–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13060

Watanabe M, Gangitano E, Francomano D, Addessi E, Toscano R, Costantini D, Tuccinardi D, Mariani S, Basciani S, Spera G, Gnessi L, Lubrano C (2018) Mangosteen extract shows a potent insulin sensitizing effect in obese female patients: a prospective randomized controlled pilot study. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050586

Poddar K, Kolge S, Bezman L, Mullin GE, Cheskin LJ (2011) Nutraceutical supplements for weight loss: a systematic review. Nutr Clin Pract 26(5):539–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533611419859

Basciani S, Costantini D, Contini S, Persichetti A, Watanabe M, Mariani S, Lubrano C, Spera G, Lenzi A, Gnessi L (2015) Safety and efficacy of a multiphase dietetic protocol with meal replacements including a step with very low calorie diet. Endocrine 48(3):863–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-014-0355-2

Bruci A, Tuccinardi D, Tozzi R, Balena A, Santucci S, Frontani R, Mariani S, Basciani S, Spera G, Gnessi L, Lubrano C, Watanabe M (2020) Very low-calorie ketogenic diet: a safe and effective tool for weight loss in patients with obesity and mild kidney failure. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020333

Castellana M, Conte E, Cignarelli A, Perrini S, Giustina A, Giovanella L, Giorgino F, Trimboli P (2019) Efficacy and safety of very low calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in patients with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-019-09514-y

Watanabe M, Tozzi R, Risi R, Tuccinardi D, Mariani S, Basciani S, Spera G, Lubrano C, Gnessi L (2020) Beneficial effects of the ketogenic diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive review of the literature. Obes Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13024

Basciani S, Camajani E, Contini S, Persichetti A, Risi R, Bertoldi L, Strigari L, Prossomariti G, Watanabe M, Mariani S, Lubrano C, Genco A, Spera G, Gnessi L (2020) Very-low-calorie ketogenic diets with whey, vegetable or animal protein in patients with obesity: a randomized pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa336

Ricci A, Idzikowski MA, Soares CN, Brietzke E (2020) Exploring the mechanisms of action of the antidepressant effect of the ketogenic diet. Rev Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2019-0073

Tuccinardi D, Farr OM, Upadhyay J, Oussaada SM, Mathew H, Paschou SA, Perakakis N, Koniaris A, Kelesidis T, Mantzoros CS (2019) Lorcaserin treatment decreases body weight and reduces cardiometabolic risk factors in obese adults: a six-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Diabet Obes Metab 21(6):1487–1492. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13655

Tsilingiris D, Liatis S, Dalamaga M, Kokkinos A (2020) The fight against obesity escalates: new drugs on the horizon and metabolic implications. Curr Obes Rep 9(2):136–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00378-x

Mariani S, Watanabe M, Lubrano C, Basciani S, Migliaccio S, Gnessi L (2015) Interdisciplinary approach to obesity. In: Lenzi A, Migliaccio S, Donini LM (eds) Multidisciplinary approach to obesity: from assessment to treatment, Springer, Cham, pp 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09045-0_28

Funding

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Data collection for the study benefitted from the annual, faculty-funded eight-week undergraduate summer research internship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The ethics committee of the University Hospital Campus Biomedico of Rome approved this study and its development. All the procedures performed in the study complied with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to start the survey. Completion of the survey pack implied consent.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The article is part of the Topical Collection on Obesity Surgery and Eating and Weight Disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sisto, A., Vicinanza, F., Tuccinardi, D. et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients included in a bariatric surgery program. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1737–1747 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00988-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00988-3