Abstract

Purpose

Theoretical models, such as the transdiagnostic model of eating disorders highlight the role of cognitive factors (e.g., the way people perceive their bodies) and their associations with maladaptive weight management behaviors resulting in underweight. This paper aims at testing the indirect association of adolescent’s body satisfaction and body mass index (BMI) through restrictive dieting, healthy eating or unhealthy eating as well as moderating role of adolescent’s weight status.

Methods

The study was conducted in 16 public middle and high schools in Central and Eastern Poland. A sample of 1042 under- and healthy-weight white adolescents aged 13–20 (BMI: 12.63–24.89) completed two self-reported questionnaires (fruit, vegetable, and energy-dense food intake) with a 11-month interval. Weight and height were measured objectively. Multiple mediation analysis and moderated multiple mediation analysis were conducted to test the study hypotheses.

Results

Adolescents less satisfied with their bodies were more likely to diet restrictively and at the same time ate more unhealthy energy-dense food rather than healthy food, which in turn predicted lower BMI. No moderating effects of weight status were found.

Conclusions

Low body satisfaction is a risk for restrictive diet and unhealthy food intake. Prevention programs may target under- and healthy-weight adolescents who are highly dissatisfied with their bodies, have a high intake of energy-dense food and apply a restrictive diet at the same time.

Level of evidence

Level III: longitudinal cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthy body weight reduces the risk of heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, osteoarthritis and other related health problems [1]. On the other hand, underweight (as well as overweight and obesity) might affect adolescents’ physical and mental health [2], and lead to eating disorders (EDs) (as shown in Zarychta, Mullan, Kruk and Luszczynska [3]) or the development of EDs symptoms that do not meet the diagnostic criteria [4, 5]. Therefore, the identification of modifiable risk factors for underweight and factors promoting healthy body weight is of key importance in the prevention of their consequences in the future.

Theoretical models (e.g., transdiagnostic model of EDs) [6] highlight the role of cognitive factors in explaining eating behaviors and body weight. They focus primarily on the way people perceive their bodies, the contents of their thoughts, and perceptions of body weight and shape. The transdiagnostic model of EDs emphasizes that people let their outer appearance affect their self-evaluations. This leads to an excessive concentration on body weight and shape, and to maladaptive weight management behaviors (i.e., restrictive dieting, compulsive overeating, extremely healthy eating) resulting in underweight.

Body weight perception is one of the key cognitive factors emphasized as a significant determinants of both nutrition behaviors (e.g., Chen et al. [7]) and body mass index (BMI) [8]. Thus, it is important to explore the influence of psychological variables on diet, as they may help promote the uptake and maintenance of healthy behaviors in this population [9, 10]. Body weight-related perceptions (e.g., body satisfaction) are most often tested in over- and underweight groups. However, they are important for adolescents in general, including those with normal body weight, as unfavorable shifts in body weight perceptions may contribute to a development of unfavorable physical and mental health outcomes [11]. The present study fills that gap by investigating body satisfaction in normal weight adolescents with reference to underweight adolescents.

It has been well documented in previous studies that body satisfaction (defined as evaluation of one’s body) and its lower level (which represents body dissatisfaction) [12] is one of the main variables associated with not only EDs [13], but also with body weight status and body mass index [11]. Lower body satisfaction (conceptualized as the equivalent of higher body dissatisfaction in this study) is also linked to other health-related determinants and outcomes including lower self-esteem [14], anxiety and depression [15] or to subclinical eating pathologies [16] and various weight control behaviors [17]. On the other hand, higher body satisfaction is associated with individuals being less likely to diet restrictively or use other weight control behaviors, and with higher frequency of physical activity [18].

Among adolescents with normal weight or underweight, lower body satisfaction leads to lower engagement in healthy eating or excessive physical activity, which in turn leads to weight loss resulting in becoming underweight or underweight maintenance [19]. Thus, research is needed to explore whether body satisfaction predicts healthy or unhealthy eating behaviors, which in turn predicts unfavorable changes in BMI (i.e., body mass reduction) in the group of under- and healthy-weight adolescents. The present study will shed some light on this issue.

Physical appearance (including e.g., weight, height and body fat percentage) significantly changes in adolescence and it becomes especially big concern for teenage girls [20]. On the other hand, lower body satisfaction related to drive for muscularity can also be found in teenage boys [21]. In particular, both females and males want to have a lean and low in body fat physiques, but males additionally desire muscular bodies (e.g., Field et al. [22]). Thus, lower body satisfaction is a growing challenge in adolescences of both genders.

Results of several cross-sectional [13, 23] and longitudinal studies [24, 25] confirmed associations of lower body satisfaction with eating pathologies such as restrictive dieting, which may lead to underweight and/or EDs. On the other hand, very few of these studies clarified the possible mechanism through which body satisfaction may explain body weight. One probable pathway is that if the level of body satisfaction constitutes a risk factor for low levels of healthy eating behaviors which in turn predicts lower healthy body weight. Moreover, most studies focused on restrictive or binge eating but whether the food intake was healthy or not (accounting for high intake of fruit and vegetable, and reducing energy-dense foods or high intake of energy-dense foods) was overlooked. The present study investigated both heathy eating and eating pathologies indicators, such as restrictive dieting or eating energy-dense foods (unhealthy eating).

The majority of previous research referred to general population of adolescents [26] or focused on overweight and obese adolescents [27, 28] suggesting that promoting body satisfaction might be most beneficial for weight loss or maintaining healthy body weight. However, it can be assumed that an investigation of the associations among body satisfaction, healthy and unhealthy eating, and BMI should account also for under- and healthy-weight adolescents.

Furthermore, to fully understand temporal effects among body satisfaction, healthy eating or unhealthy dieting and body mass index (BMI), self-reported variables should be measured at separate time points [29]. Unfortunately, most of research so far has mostly included one measurement point [30,31,32]. The hypotheses in the present study will be tested using two measurement points to establish temporal precedence.

The aim of this prospective study was to investigate the associations between body satisfaction, healthy and unhealthy eating, restrictive dieting, and adolescents’ BMIs in a non-clinical sample of adolescents with underweight or healthy-weight. We hypothesized that the long-term indirect effects of body satisfaction on adolescent’s BMI will go rather through restrictive dieting than through either healthy or unhealthy eating. In particular, we hypothesized that:

-

the indirect effect of body satisfaction (Time 1; T1) on BMI (T2) would be mediated by healthy eating (Time 2; T2); (Hypothesis 1; H1);

-

the indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) on BMI (T2) would be mediated by unhealthy eating (T2) (H2);

-

the indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) on BMI (T2) would be mediated by restrictive dieting (T2) (H3);

-

body satisfaction (T1) associations with healthy eating (T2), unhealthy eating (T2) and restrictive dieting (T2) would be moderated by body weight status (1—underweight, 2—normal weight) (H4).

As previous research established that sex [33, 34], age [35] and BMI [36] may be relevant determinants of the cognitive and behavioral ED risk factors, all three hypotheses were tested accounting for the effects of sex, age and BMI (T1) on the dependent variable, that is BMI at T2.

Method

Participants

At Time 1 (T1; baseline), 1297 adolescents (58.2% girls) aged 13–20 years (M 16.54, SD 0.90) with BMIs ranging from 12.63 to 41.21 (M 22.30, SD 3.77) participated in the study, of whom 33 (2.6%) adolescents were underweight, 888 (69.1%) had normal body weight, 257 (19.8%) were overweight, and 107 (8.2%) obese (calculated according to WHO growth reference for children and adolescents; de Onis et al. [37]). At Time 2 (T2; 11 months later), a total of 911 (52.3% girls) adolescents aged 14–20 years (M 17.19, SD 0.93) with BMIs ranging from 14.24 to 39.66 (M 22.13, SD 3.97) participated in the study. At T2, 33 (3.6%) participants were underweight, 681 (74.8%) had normal body weight, 145 (15.9%) were overweight, 52 (5.7%) or obese. Overweight (n = 257) and obesity (n = 107) were identified as an exclusion criterion in the study, since the mechanisms related to their higher weight might be different than in the groups with underweight or normal weight. All participants were white. The majority (64%) lived in urban areas, with 36% living in rural areas.

The total attrition rate was 29.8%. Missing data from those who dropped out at T2 were imputed. Therefore, data collected from N = 1042 adolescents (63.8% girls) aged 13–20 years (M 16.54, SD 0.88) with BMIs ranging from 12.63 to 24.89 (M 22.57, SD 1.98) were included in the analyses.

Procedure

The study was conducted in 16 public middle and high schools in Central and Eastern Poland. For all participants T2 data were collected at 11 months after T1. All potential respondents lived with their parents (98.9%) or other legal guardians (1.1%) at T1 and T2. Participants and parents of individuals younger than 18 years provided informed consent before the study. Adolescents were informed about the objectives, the procedure and the possibility of refusing to participate in the study (in this case access to school’s library or dayroom was provided). Personal codes were assigned to secure anonymity and identification across the measurement points. Participants were asked to provide their data referring to their nutrition behaviors and body satisfaction. At T1, participants completed a questionnaire measuring their body satisfaction, and at T2 participants (70.2% of those who completed T1) filled in a questionnaire regarding their eating behaviors. At both T1 and T2, participants have their height and weight measured. Researchers were available for consultations after the study completion and made multiple efforts to reduce attrition. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee at University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poland. The procedures of the study were described in more detail in a paper by Zarychta et al. [10].

Materials

The hypotheses in the present study are tested using two measurement points to establish temporal precedence [29]. Thus, the independent variable was measured at T1, and the mediators and dependent variable at T2.

Body satisfaction (T1)

Body satisfaction variable consisted of seven items, based on The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire’s Appearance Evaluation Subscale (MBSRQ; Cash [38]). The measure assesses feelings of physical attractiveness or unattractiveness with high scores indicating higher satisfaction with one’s appearance and low scores indicating general unhappiness with one’s appearance. In order to assess it, the respondents were asked to read seven statements (e.g., “I like my looks just the way they are”, “Most people would consider me good-looking” and “I like the way I look without my clothes on”) and decide how much each statement pertains to them. The responses ranged from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree).

Healthy eating (T2)

In order to evaluate healthy eating, two questions adopted from Lally, Bartle and Wardle [39] were used: “How often did you eat a portion of fresh fruit in the last two weeks?” and “How often did you eat a portion of vegetables in the last two weeks (fresh, boiled or fried without fat)?”. The portion was defined as the amount fitting into a cupped hand. The responses were given on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (once a week or less) to 6 (four or more times a day).

Unhealthy eating (T2)

In order to evaluate unhealthy eating, adolescents answered two questions, adopted from Lally, Bartle and Wardle [39]: “How often did you eat fatty foods (e.g., pizza, chips, foods with dressings) in the last two weeks?” and “How often did you eat sweets (e.g., chocolate bars or wafers, cakes) in the last two weeks?”. The responses were given on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (once a week or less) to 6 (four or more times a day).

Restrictive dieting (T2)

In line with research conducted so far on overall diet quality (cf. Loftfield et al. [40]), the measurement of dietary restrictions was based on a single item adopted from MBSRQ [38]: “I am on a restrictive weight-loss diet”. The responses ranged from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree).

Body weight and height (T1 and T2)

Biometric measures were assessed with standard medically approved telescopic height measuring rods and floor scales (scale type: BF-100 or BF-25). Age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles were calculated with WHO AnthroPlus macro [41], based on the WHO growth reference [37] for children and adolescents. BMI z-scores were calculated and used as independent variables in both analyses. Also, two weight status categories were created based on BMIs’ SD cut-offs (− 1—underweight [less than or equal to 2 SD], + 1—normal weight) [37].

Data analysis

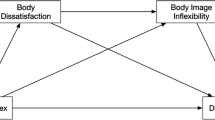

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. Multiple mediation analysis was performed to test the relation between body satisfaction, healthy eating, unhealthy eating or restrictive dieting, and adolescents’ BMIs with the use of PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 10,000 bootstraps [42]. Analyses were conducted accounting for the covariates (T1 BMI, age and sex [coded as 1 for males and 2 for females]). Results are presented using two types of coefficients: (1) the regression coefficient for each parameter (see Fig. 1), and (2) the indirect effect coefficient (B) for each indirect pathway between the independent variable (T1 body satisfaction) and the dependent variable (T2 BMI), accounting for respective mediators (see Fig. 1; Table 2). Furthermore, sex, age, and BMI (T1) were included into each regression model as predictors of the dependent variable, BMI at T2. This way potential confounders and BMI at T1 were controlled for.

Additionally, moderated multiple mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro (Model 58). In particular, these analyses tested if the associations between (1) the independent variable and the mediator, and (2) the mediator and the dependent variable are moderated by participants’ weight status.

In the current study the independent variable (IV) was body satisfaction (T1); the dependent variable (DV) was BMI z-score measured at T2; the mediators were healthy eating (T2), unhealthy eating (T2) and restrictive dieting (T2); moderator was weight status (T1) coded as − 1 for underweight and + 1 for normal body weight.

In order to establish temporal precedence [29], the variables were measured at different time points (T1 and T2). Missing data were imputed with multiple imputation method [43]. A total of 5.9% of the completers’ data were missing. The attrition analysis is presented below.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive findings and attrition analysis

Means, standard deviations, results of variance analyses and reliability coefficients are presented in Table 1.

Completers did not differ from those who dropped out at T2 in terms of the body satisfaction, healthy eating, unhealthy eating, restrictive dieting and BMI, all Fs < 3.21, ps > 0.15, or sex, χ2 (1) = 2.70, p = 0.14. Dropouts and completers differed in terms of age, F (1, 1296) = 62.17, p < 0.0001 with dropouts being slightly older (M 16.82, SD 0.64) than completers (M 16.40, SD 0.98, Cohen’s d = 0.50 [95% CI 0.46–0.55]).

Correlation analyses and comparisons between adolescents with underweight and normal body weight

Correlations between study variables for the study sample (N = 1042) are presented in Table 1. There were weak negative correlations between body satisfaction (T1) with restrictive dieting (T1 and T2), adolescents’ BMI (T1 and T2), their age and sex. Healthy eating (T1 and T2) was weakly and negatively associated with restrictive dieting (T1 and T2). On the other hand, unhealthy eating (T1 and T2) was weakly and positively associated with restrictive dieting (T1 and T2). Moreover, restrictive dieting (T1 and T2) was weakly and negatively correlated with adolescents’ BMI (T1 and T2), and their sex (see Table 1).

No significant differences were found between adolescents with underweight and normal body weight in terms of body satisfaction (T1), healthy eating (T2), unhealthy eating (T2) or restrictive dieting (T2), all Fs < 2.12, ps > 0.15 (see Table 1).

Indirect effect of body satisfaction mediated by healthy eating

For the first three hypotheses one multiple mediation model (Model 4, which allows up to 10 mediators operating in parallel) was conducted.

H1 tested the indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) (IV) on adolescents’ BMI (T2) (DV) mediated by healthy eating (T2) (see Fig. 1). It was measured controlling for BMI (T1), adolescents’ sex and age.

The results of multiple mediation analysis for H1 (see Table 2) indicated no significant indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) on adolescents’ BMI (T2). Also, we did not find any direct associations between these three variables. Additional moderation analysis, assuming that the associations between body satisfaction, healthy eating, and adolescents’ BMI were moderated by sex, indicated that these associations were the same for girls and boys.

Indirect effect of body satisfaction mediated by restrictive dieting

H2 tested the indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) (IV) on adolescents’ BMI (T2) (DV) mediated by unhealthy eating (T2) (see Fig. 1). Analysis was conducted controlling for BMI (T1), adolescents’ sex and age.

The results of multiple mediation analysis for H2 (Table 2) showed that the association between body satisfaction (T1) and adolescents’ BMI (T2) was mediated by unhealthy eating (T2) as indicated by the significant indirect effect. Adolescents who were unhappy with their appearance (T1) eat unhealthy food more often (T2) and predicted lower BMI at T2. Direct association between IV (T1), mediator (T2), and DV (T2) is presented in the Fig. 1.

Indirect effect of body satisfaction mediated by restrictive dieting

H3 tested the indirect effect of body satisfaction (T1) (IV) on adolescents’ BMI (T2) (DV) mediated by restrictive dieting (T2) (see Fig. 1). Analysis was conducted controlling for BMI (T1), adolescents’ sex and age.

The results of multiple mediation analysis for H3 (Table 2) showed that the association between body satisfaction (T1) and adolescents’ BMI (T2) was mediated by restrictive dieting (T2) as indicated by the significant indirect effect. Adolescents who were unhappy with their appearance (T1) were also dieting restrictively more often (T2) and thus had lower BMI at T2. Direct association between IV (T1), mediator (T2), and DV (T2) is presented in the Fig. 1. The analyses assumed that the associations between body satisfaction, restrictive dieting, and adolescents’ BMI were moderated by sex, indicated that these associations were the same for girls and boys.

Testing the moderating role of body weight status

To test whether body weight status act as a moderator of the associations between (1) body satisfaction (T1) (IV) and healthy eating (T2), unhealthy eating (T2) and restrictive dieting (T2) (mediators), and (2) between mediators (T2) and BMI (T2) (DV), moderated multiple mediation analysis (Model 58, which allows up to 10 mediators operating in parallel) was conducted controlling for BMI (T1), adolescents’ sex and age.

The results of moderated multiple mediation analysis (Table 2) showed no significant effects of body weight status on any of above-mentioned associations. Additional multiple moderation analysis, assuming that the associations between body satisfaction, unhealthy eating, and adolescents’ BMI were moderated by sex, indicated that these associations were the same for girls and boys.

Discussion

This study provides novel evidence for the long-term indirect effects of body satisfaction on adolescents’ BMI through restrictive dieting, healthy and unhealthy eating in the non-clinical group of under- and healthy-weight adolescents. The results show that body satisfaction is indirectly linked to adolescents’ BMIs through restrictive dieting but also through unhealthy eating. However, the mediating effects were not found for healthy eating. In particular, lower body satisfaction at T1 predicted more unhealthy eating and restrictive dieting at T2 which in turn predicted lower BMI at T2.

In contrast to previous cross-sectional research (e.g., Tylka [13]) or research which explored direct associations between variables presented in our study (e.g., Mendonça et al. [23]), this research permitted a more thorough testing of associations between body satisfaction, healthy and unhealthy eating, restrictive dieting and BMI in the non-clinical group of under- and healthy-weight adolescents. Thus, our research expands on previous research conducted in general population of adolescents [26] or only in groups of overweight and obese adolescents [27, 28], and shows that these associations are true also across under- and healthy-weight adolescents and in a large sample of both male and female participants. Moreover, we found no significant moderating effect of sex, which means that associations between study variables were the same for both sexes. This is congruent with previous studies (e.g., Field et al. [22]) that indicated that both females and males might behave similarly in terms of eating, but the purposes of such behaviors might be different. For girls it is having a lean body, and for boys it is having lean and muscular body.

Previous research [18, 44] confirmed that body satisfaction mattered, being a predictor of dieting and other types of weight control behaviors or binge eating. However, no studies tested if body satisfaction predicts healthy or unhealthy eating behaviors, which in turn predicts unfavorable changes in BMI. The present study filled that gap indicating that body satisfaction is not only a predictor of restrictive dieting, but also of unhealthy eating, and both these associations mediate the relationship between body satisfaction and adolescents’ BMIs. Thus, theoretical models analyzing body satisfaction role (e.g., Fairburn [6]) should account not only for dietary restrictions but also for energy-dense eating.

The main limitation of the study refers to an exclusion of affective and other cognitive processes which explain ED symptoms and body weight according to cognitive-behavioral models. Assuming small effects of cognitions and behaviors on changes in body mass (T1–T2), an addition of further emotional, cognitive and behavioral processes would require a larger sample to secure good power of analyses. Moreover, it has to be taken into account that the outcomes may be affected by social desirability bias and the composition of the study sample, i.e., a non-clinical sample of under- and healthy-weight adolescents. This study aimed at indicating potential mechanisms of developing ED (and lower body weight as one of its main symptoms), though. Therefore, a clinical sample of patients with ED has been found to be inappropriate to achieve this aim. Yet, there was no screening for ED symptoms performed in this study. Thus, the results may refer to a general population including both adolescents with and without ED symptoms. Another limitation are low beta coefficients obtained in this study indicating weak associations between the variables and in consequence the results should be interpreted cautiously. Reliability of the single-item measure of dieting may be limited, but its usage has been justified in previous research [e.g., 40]. Alternatives may be considered in the future, though. Moreover, body weight depends on eating behaviors but also on energy expenditure levels, that is physical activity. Thus, to fully understand the links between body satisfaction and body weight, both eating behaviors and physical activity should be accounted for in future research. Finally, we did not account for other factors previously found to be significant for the association between body satisfaction and ED symptoms, such as negative affect [45], depressed mood [46], emotion regulation [47], gender differences and personality traits [48], maladaptive perfectionism [49], self-esteem [50] or socio-economic status [51].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study confirmed associations between body satisfaction, unhealthy eating and restrictive dieting and adolescents’ BMIs, specifically in the group of under- and healthy-weight adolescents. These results indicate that the inclusion of cognitive factors such as body satisfaction, and behavioral symptoms of ED such as unhealthy eating and restrictive dieting in most treatment and prevention programs of ED is justified and should continue. Our findings, however, suggest that ED prevention or treatment programs might target not only adolescents from clinical samples, but also under- and healthy-weight adolescents who are at risk of unhealthy eating and at the same time dieting restrictively, and who are highly dissatisfied with their bodies, especially.

References

Stein CJ, Colditz GA (2004) The epidemic of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(6):2522–2525. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0288

Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2015) Adolescent eating disorders. Update on definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 24(1):177–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.08.003

Zarychta K, Mullan B, Kruk M, Luszczynska A (2017) A vicious cycle among cognitions and behaviors enhancing risk for eating disorders. BMC Psychiatry 17(1):154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1328-9

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Zarychta K, Luszczynska A, Scholz U (2014) The association between automatic thoughts about eating, the actual-ideal weight discrepancies, and eating disorders symptoms: a longitudinal study in late adolescence. Eat Weight Disord Stud 19(2):199–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0099-2

Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. The Guilford Press, New York

Chen H, Lemon SC, Pagoto SL, Barton BA, Lapane KL, Goldberg RJ (2014) Personal and parental weight misperception and self-reported attempted weight loss in US children and adolescents, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2008 and 2009–2010. Prev Chronic Dis 11:140123. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.140123

Perkins JM, Perkins HW, Craig DW (2010) Peer weight norm misperception as a risk factor for being over- and underweight among UK secondary school students. Eur J Clin Nutr 64:965–971. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.106

Luszczynska A, de Wit JBF, de Vet E, Januszewicz A, Liszewska N, Johnson F, Pratt M, Gaspar T, de Matos MG, Stok FM (2013) At-home environment, out-of-home environment, snacks and sweetened beverages intake in preadolescence, early and mid-adolescence: the interplay between environment and self-regulation. J Youth Adolesc 12:1873–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9908-6

Zarychta K, Mullan B, Luszczynska A (2016) Am I overweight? A longitudinal study on parental and peers weight-related perceptions on dietary behaviors and weight status among adolescents. Front Psychol 7:83. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00083

Quick V, Wall M, Larson N, Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D (2013) Personal, behavioral and socio-environmental predictors of overweight incidence in young adults: 10-year longitudinal findings. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 25:10–37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-37

Stice E, Shaw HE (2002) Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res 53(5):985–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9

Tylka TL (2004) The relation between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology: an analysis of moderating variables. J Couns Psychol 51(2):178–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.178

Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME (2006) Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 35(4):539–549. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5

Presnell K, Stice E, Seidel A, Madeley MC (2009) Depression and eating pathology: prospective reciprocal relations in adolescents. Clin Psychol Psychot 16(4):357–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.630

Allen KL, Byrne SM, La Puma M, McLean N, Davis EA (2008) The onset and course of binge eating in 8- to 13-year-old healthy weight, overweight and obese children. Eat Behav 9(4):438–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.07.008

Westerberg-Jacobson J, Ghaderi A, Edlund B (2012) A longitudinal study of motives for wishing to be thinner and weight-control practices in 7- to 18-year-old Swedish girls. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1145

Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M (2006) Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health 39(2):244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

Mond J, Rodgers B, Hay P, Owen C (2011) Mental health impairment in underweight women: do body dissatisfaction and eating-disordered behavior play a role? BMC Public Health 11:547. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-547

Bratovcic V, Mikic B, Kostovski Z, Teskeredzic A, Tanovic I (2015) Relations between different dimensions of self-perception, self-esteem and body mass index of female students. Int J Morphol 33(4):1338–1342. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022015000400024

Daniel S, Bridges SK (2010) The drive for muscularity in men: media influences and objectification theory. Body Image 7(1):32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.08.003

Field AE, Sonneville KR, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Eddy KT, Camargo CA Jr, Horton NJ, Micali N (2014) Prospective associations of concerns about physique and the development of obesity, binge drinking, and drug use among adolescent boys and young adult men. JAMA Pediatr 168(1):34–39. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2915

Mendonça KL, Sousa ALL, Carneiro CS, Nascente FMN, Póvoa TIR, Souza WKSB., Jardim TSV, Jardim PCBV. (2014) Does nutritional status interfere with adolescents’ body image perception? Eat Behav 15(3):509–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.011

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Calogero R, Fida R, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G (2014) The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(8):997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1

Goldschmidt AB, Wall M, Choo TH, Becker C, Neumark-Sztainer D (2016) Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychol 35(3):245–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000283

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, McLean SA (2014) A biopsychosocial model of body image concerns and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. J Youth Adolesc 43(5):814–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0013-7

Sonneville KR, Calzo JP, Horton NJ, Haines J, Austin SB, Field AE (2012) Body satisfaction, weight gain and binge eating among overweight adolescent girls. Int J Obesity 36:944–949. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.68

van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D (2007) Fat ‘n happy 5 years later: is it bad for overweight girls to like their bodies? J Adolesc Health 41(4):415–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.001

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum, Mahwah

Chang FM, Jarry JL, Kong MA (2014) Appearance investment mediates the association between fear of negative evaluation and dietary restraint. Body Image 11(1):72–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.11.002

Jung J, Forbes GB, Lee Y (2009) Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among early adolescents from Korea and the US. Sex Roles 61(1–2):42–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9609-5

Mäkinen M, Puukko-Viertomies L, Lindberg N, Siimes MA, Aalberg V (2012) Body dissatisfaction and body mass in girls and boys transitioning from early to mid-adolescence: additional role of self-esteem and eating habits. BMC Psychiatry 12:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-35

Donovan CL, Spence SH, Sheffield JK (2006) Investigation of a model of weight restricting behaviour amongst adolescent girls. Eur Eat Disord Rev 14(6):468–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.711

von Soest T, Wichstrom L (2009) Gender differences in the development of dieting from adolescence to early adulthood: a longitudinal study. J Res Adolesc 19:509–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00605.x

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2001) Dietary restraint and negative affect as mediators of body dissatisfaction and bulimic behavior in adolescent girls and boys. Behav Res Ther 39(11):1317–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00097-8

Deschamps V, Salanave B, Chan-Chee C, Vernay M, Castetbon K (2015) Body-weight perception and related preoccupations in a large national sample of adolescents. Pediatr Obes 10(1):15–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00211.x

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85(9):660–667. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.043497

Cash TF (2000) Users’ manual for the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. http://www.body-images.com. Accessed 15 Apr 2017

Lally P, Bartle N, Wardle J (2011) Social norms and diet in adolescents. Appetite 57:323–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.07.015

Loftfield E, Yi S, Immerwahr S, Eisenhower D (2015) Construct validity of a single-item, self-rated question of diet quality. J Nutr Educ Behav 47(2):181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.09.003

World Health Organization (2011) WHO Anthro (version 3.2.2, January 2011) and macros. http://www.who.int/growthref/tools/en. Accessed 12 Apr 2017

Hayes AF (2013) An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. The Guilford Press, New York

Enders CK (2010) Applied missing data analysis. The Guilford Press, New York

Oellingrath IM, Hestetun I, Svendsen MV (2015) Gender-specific association of weight perception and appearance satisfaction with slimming attempts and eating patterns in a sample of young Norwegian adolescents. Public Health Nutr 19(2):265–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001007

Grilo C (2004) Subtyping female adolescent psychiatric inpatients with features of eating disorders along dietary restraint and negative affect dimensions. Behav Res Ther 42(1):67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00073-1

Hinchliff GLM, Kelly AB, Chan GCK, Patton GC, Williams J (2016) Risky dieting amongst adolescent girls: associations with family relationship problems and depressed mood. Eat Behav 22:222–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.06.001

Sim L, Zeman J (2006) The contribution of emotion regulation to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. J Youth Adolesc 2:207–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9003-8

Cuzzocrea F, Larcan R, Lanzarone C (2012) Gender differences, personality and eating behaviors in non-clinical adolescents. Eat Weight Disord 17(4):282–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325139

Costa S, Hausenblas HA, Oliva P, Cuzzocrea F, Larcan R (2016) Maladaptive perfectionism as mediator among psychological control, eating disorders, and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser. J Behav Addict 5(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.004

Raykos BC, McEvoy PM, Fursland A (2016) Socializing problems and low self-esteem enhance interpersonal models of eating disorders: evidence from a clinical sample. Int J Eat Disord 50(9):1075–1083. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22740

Tuinstra J, Groothoff JW, van den Heuvel WJ, Postab D (1998) Socio-economic differences in health risk behavior in adolescence: do they exist? Soc Sci Med 47:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00034-3

Funding

The preparation of this paper was supported by the grant BST/Wroc/2017/B/11 awarded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Republic of Poland to Karolina Zarychta, Ph.D. and by the Grant BST/Wroc/2017/A/07 awarded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Republic of Poland to Aleksandra Luszczynska, Ph.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee at University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poland, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all adolescents participating in the study and from their parents (in case adolescents were younger than 18 years).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zarychta, K., Chan, C.K.Y., Kruk, M. et al. Body satisfaction and body weight in under- and healthy-weight adolescents: mediating effects of restrictive dieting, healthy and unhealthy food intake. Eat Weight Disord 25, 41–50 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0496-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0496-z