Abstract

The organ shortage has become a crisis for transplant candidates with end-stage renal disease, and a significant number of them either die while waiting or become too sick to transplant. A consequence, worldwide, has been the development of unregulated markets for donation; these markets have been associated with poor outcomes for both donors and recipients. In contrast, a regulated system of incentives might increase donation rates while also providing a benefit to donors. Criteria for an acceptable system have been proposed: protection of the donor and recipient, regulation, transparency, and oversight. Many of the concerns about the implications and impact of such a system could be answered with a clinical trial in a country (or countries) that can meet the described standards. Yet the debate about the advisability of developing such a system continues, even as the waiting lists grow and candidates die while waiting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The optimal treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease is a kidney transplant. Yet most countries that offer transplants have a shortage of organs. As a consequence, waiting times are long, and many accepted candidates either die while waiting or become too sick to transplant.

No single cause accounts for the organ shortage. Some countries have active living donor programs, but limited (or no) deceased donor programs. For some countries, the cost and logistics of developing a national deceased donor program can be prohibitive; other countries face insurmountable cultural barriers such as stigma associated with donation, or religious beliefs about the care of the body [1•]. Conversely, some countries have emphasized deceased donation and have not encouraged living donation. Finally, some countries have maximized (or nearly maximized) both living and deceased donation — and still have a significant shortage. A consequence of the organ shortage is that unregulated, underground markets for donation have developed in many countries (over many continents) [2–18].

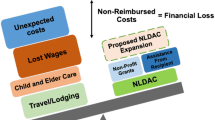

Living donor transplants are associated with the best outcomes after kidney transplantation. In most countries, however, the financial disincentives to living donation are numerous (Table 1). Living donors not only give up a significant amount of their time, but also undertake the risks of surgery for a procedure that is of no physical benefit to them. In many countries, donors and donor candidates must, in effect, pay for the “privilege” of being a donor: they bear both the expense of traveling to the transplant center for evaluation and then, if approved, the expense of traveling to the transplant center for the surgery. Most living donors are not reimbursed for lost wages or for any other costs of donation, such as child care.

In 2006, Clarke et al reviewed 35 studies from 12 countries that looked at living donor costs. Of those studies, 17 (49 %) were from the United States, 12 from Western Europe, two each from Canada and Australia, and one each from Japan and Iran [19]. Of the living donors described, 9 % to 99 % of them claimed travel and/or accommodation costs (costs that were higher in countries with a larger land mass). In addition, 14 % to 30 % of the living donors in those 35 studies incurred costs for lost income; 9 % to 44 %, costs for dependent care; and 8 %, costs for domestic help.

A subsequent study from Australia found that the major financial concerns for living donors were the costs of testing, the extra costs associated with living in a nonurban area, and lost wages [20]. Even though Australia has a public health system, prospective donors living in nonurban areas often had no local access to the system, and consequently, underwent initial testing at a private hospital where they had to pay upfront.

In a more recent study of 100 prospectively enrolled living donors in Canada, the economic consequences of donation were evaluated at 3 and 12 months postdonation [21••]. The authors reported that 96 % of donors suffered economic consequences; 94 % incurred travel costs, and 47 % lost wages. The average cost per donor was $3,268 (SD, $4,704); 33 % had costs greater than $3,000 and 15 % greater than $8,000.

In the United States, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) established a grant to help remove donor financial disincentives [22]. For living donors to be eligible, the grant must be the payer of last resort (i.e., they must have no other funds from federal, state, or local government or from health insurance); moreover, both the donor and the recipient must meet strict eligibility guidelines (Table 2). To date, a total of 1,941 approved applicants have proceeded to donation; the average mean expenses for travel have been $2,767.

Most countries performing living donor transplants have not specifically looked at out-of-pocket donor costs. Sickand et al compiled a list of what many countries do and do not support [23]. In the United States, the importance of costs in the decision-making process of prospective donors can be seen in the relationship between living donation rates and the economy [24]. When the economy deteriorated in 2004, living donation rates either remained unchanged or improved among the segment of the US population with income in the top 40 %, but donation rates fell significantly among those in lower income brackets.

Other disincentives to living donation exist. In countries without universal health care, prospective donors might not have insurance to cover subsequent complications or even to pay for routine follow-up care. Often, prospective donors are concerned that donation might limit their employment opportunities; lessen their ability to change jobs, for fear of being unable to obtain health insurance; or increase their life or health insurance premiums or, even worse, lead to denial of insurance altogether. Boyarsky et al, in a single-center study in the United States, surveyed former donors to determine whether or they had difficulty either changing or initiating health or life insurance postdonation; 7 % reported problems with health insurance and 25 % with life insurance [25•].

A regulated system of incentives might alleviate problems for both living donors and recipients. Such a system might increase donation rates, eliminate donor disincentives, and provide an incentive to balance both the risk and the time taken. Thus, the overall rationale for considering a system of incentives is that it might increase donation, thereby saving lives and increasing the quality of life of recipients while at the same time compensating donors for their health and financial risks.

An additional potential advantage of a regulated system is that the associated increase in organ donation might decrease the current illegal business of unregulated, underground kidney markets.

Varying Views

Public Opinion on Incentives

To date, surveys from a number of countries—Canada, the Netherlands, the Philippines, the United States—have suggested that the public is in favor of incentives and/or would be more likely to donate if incentives existed [26•, 27–44]. In actuality, a truly universal viewpoint does not exist and may vary between countries, just as cultures vary between countries.

Donor Motivations

An important component of the discussion on incentives for donation is consideration of the significance of altruism. Often, opponents of incentives naively create a dichotomy between “altruism” and “incentives,” insisting that all donations must be purely altruistic. (That insistence is what has led to a shortage of organs worldwide.) In reality, published studies suggest that, rather than a dichotomy, more of a continuum prevails, with mixed motives for living donation [45, 46, 47••]. For example, the three major Western religions all put high value on the saving of a life. Each has a saying similar to “the person who saves a life saves the world.” Living donors with altruistic motives might also need and/or appreciate any benefits that are provided, or they might even donate, at least in part, because of such benefits and still have altruistic motives. Because of the complexities of motivations and the immeasurable value of saving a life, both the Philippines and Iran [47••, 48–53], two countries with a system of incentives in place, consider the incentive as a token of appreciation: in their system, the donor is respected and rewarded for the act of donation.

A few studies have specifically addressed the question of whether individuals would be more likely to donate if an incentive were involved. Each of those studies found that the majority of those individuals said that an incentive would not change their mind, but a significant percentage stated they would be more likely to donate. (To put this into perspective, in the United States, more than 100,000 transplant candidates are on the kidney waiting list; if only 0.03 % obtained a living donor because disincentives were removed and an incentive provided, the waiting list could be eliminated.)

Cultural Context

All countries performing transplants have an organ shortage. Still, it is unclear whether or not a universal decision could or should be made to implement incentives for living donors. Those of us in the transplant community might all agree, in theory anyway, on certain principles, e.g., opposition to exploitation of poor and vulnerable people. Yet, within that context, cultures (including the realities of medical practice) differ from country to country, and potential solutions to the organ shortage similarly differ. Examples of cultural differences are delineated in the ethnographic work of Fry-Revere in Iran and Moazam in Pakistan [47••, 54].

Writing about the differences in informed consent practices in Iran (versus developed countries in the Western world), Fry-Revere notes that physicians respect the concept of informed consent. But, in part because of physician shortages, they feel that, if they took the time to answer all patient and family questions, the “process of treatment would get bogged down” and they would not be able to see as many patients in 1 day; in fact, some patients “might not be seen in time and some might not be seen at all” [47•• p.48].

Writing about kidney donation in Pakistan, another developing country, Moazam makes similar comments about informed consent [54 p. 25]. In that culture, patients trust that physicians will respect them and will make the right decision for them. Importantly, Pakistan has very limited resources for dialysis, and physicians often need to decide who to accept (versus deny) for dialysis [54 p. 91]. Those who are accepted most often must pay for dialysis; and, the vast majority of the population cannot pay for long-term dialysis. In this context, Moazam notes that “patients are perceived as powerless in the face of life-disease” and that “each patient is seen as deserving of a cure [whose] vulnerability is seen as compounded in instances where none of their family members are willing to donate a kidney.” Accordingly, physicians and other members of the health care staff feel “an ethical duty” to such vulnerable patients “to come to the rescue.” Moazam points out that “the staff begins with the premise … (that) an autonomous decision is unlikely by patients and their family members” and therefore (the staff) “do not travel the path of noninterference paved with intellectual detachment and information provided in a dispassionate manner.” Instead, they “interfere actively in the lives of patients and their families as they attempt to ferret out donors; they reason, but they also prod, push, control, and threaten [54 p.111].”

Moazam gives examples of physicians and other staff members telling family members that, unless someone steps forward to be a living donor, dialysis will be stopped. In contrast to their Western medicine counterparts, the encounters of Pakistani physicians with their patients and families are “colored by a Pakistani ethos of relationships and duties.” They would consider as “alien concepts” the following principles, so common in developed countries: “compassion without emotional investment, a concern for the patient uncoupled with personal engagement and a focus on the rights of individuals: [54 p. 121]”.

Unregulated Experience

To date, the experience with incentives for donation has mostly occurred in the context of unregulated, underground markets, which have developed worldwide. As a result, it is unknown how many such transplants have been done; one estimate is 10 % of all transplants worldwide [2]. Also unknown are statistics on donor and recipient outcomes after such transplants. In these unregulated, underground markets, prospective donors are often poorly informed, inadequately screened, not allowed to change their minds, given little postdonation care and no follow-up, and are often not even rewarded with the incentive that was promised [3–14]. In general, reports from the countries that have underground markets indicate that many donors regret their participation; unknown is whether or not any donors from the same countries feel that they benefited. As well, because of poor donor screening, recipients often develop serious infections; some have reportedly returned to their home countries without any information about their immunosuppressive protocol or their immediate posttransplant course. Even worse, recipients have often arrived with concomitant acute rejection and infection [15–17, 55, 56].

An additional problem with these unregulated, underground markets is that the kidney recipients have generally come from two populations: (1) wealthy citizens and (2) foreigners who can afford to travel and pay the market price. Citizens who cannot afford the market price are left to die. Ethically, serious concerns should and do arise about the rich buying from the poor, both within and between countries.

Two exceptions to this general negative experience must be noted: in the Philippines and in Iran. Both of these systems have some element of regulation.

Philippines

Underground, unregulated markets have been reported from the Philippines. However, a hospital in Manila receives government funds to facilitate kidney transplants for individuals who could not otherwise afford one. Within this specific system, a government-approved program allows “gratitudinal gifts” to nonrelated donors. These gifts can include health and life insurance, reimbursement for lost income, an educational plan, and job placement. Although the numbers are small, Manauis et al reported that living donors in Manila benefit from having improved socioeconomic status [48].

Iran

Two bodies of literature, both emanating from within Iran, offer conflicting accounts of the Iranian system. One, represented by Ghods et al, suggests that the incentives system, although not perfect, has had a positive result for both recipients (Iran does not have a long waiting list for kidney transplants) and donors (they benefit from donation and have no regrets) [48–53, 57, 58]. The other body of literature, represented by Zargooshi et al, asserts that the system does not work, that living donors are treated badly, and that they regret proceeding with donation [59, 60]. For those of us outside Iran, knowing where the truth lies is thus difficult.

Recently, Fry-Revere traveled to Iran in an effort to understand better and describe the Iranian system [47••]. While there, she visited different areas of the country and concluded that “one static system” does not exist in Iran; rather, “regulations, guidelines, and practices governing transplantation have evolved over time” and “implementation can vary considerably from region to region” [47•• p. 212]. She noted that the Iranian parliament approved the formation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to work with kidney disease patients and (incentivized) prospective donors, in order to help “depersonalize the process and standardize procedures.” Those NGOs also function as charities to help raise funds to provide to living donors.

The national government in Iran provides a monetary incentive to living donors (which equals about a third of the average individual income), 1 year of health insurance, and, for men, an exemption from the country’s 2-year military service requirement [47•• p. 51]. In many regions, donors receive more than 1 year of health insurance not only for themselves, but also for their families; in some regions, donors can come back indefinitely to their recipient’s clinic for health care postdonation. In addition to these benefits, matched donors and recipients can also negotiate an additional benefit (often the equivalent of 1.3 times the average individual income). In parts of the country where are able to raise money, they provide any negotiated additional donor benefit for recipients who cannot afford it; in reality, for most donors throughout Iran, the benefit is provided by the NGOs (Sigrid Fry, personal communication). The NGOs also pay for all the testing before donation and for all donor travel expenses. Foreigners were initially accepted in the system, but the process has now been restricted to Iranian citizens. Throughout her travels, Fry-Revere interviewed donors, recipients, and administrators. Although she did encounter some donors who felt cheated and mistreated (most often feeling that they should have been paid more), “most did not regret their donation” [47•• p. 91].

Comment

Both the isolated setup in the Philippines and the more general one in Iran suggest that developing an acceptable regulated system of incentives might be possible in other countries. Both the Philippines and Iran are working to improve their programs; nonetheless, in both countries, negotiations between donors and recipients persist and are often ethically problematic. In the Philippines, access to transplants is generally limited to the wealthy; the situation in Iran is less clear.

An Acceptable Regulated System?

A fully regulated, government-sponsored system of incentives for donation could minimize the inequalities and abuse that have been reported in unregulated, underground markets. The arguments in favor of such a system have been presented in detail [61–79, 80••]. Such a system would feature full donor evaluations and acceptance criteria similar to the current evaluations of prospective living donors in the United States and other Western countries (United States and other Western countries are cited as examples because the author is familiar with their systems); provision of the incentive by the government (or a government-approved agency), so that all donors would receive something of equal value; anonymity between donors and recipients; allocation of the kidney to the number-one candidate on the waiting list (similar to the allocation algorithm for deceased donors currently in place in the United States and other Western countries), so that all transplant candidates on the list have an opportunity for a transplant; and full protection for donors and recipients.

Each system would be limited to individual countries (or areas such as Eurotransplant that share organs); only that country’s citizens and legal residents would be able to participate. Each country/system would need to determine possible incentives. First, all donor disincentives (e.g., lack of health insurance, costs of traveling to and from the transplant center, and lost wages) should be eliminated. A menu of choices for the incentive could be offered, because different things might be of value to different donors. In 2012, an international group met in Manila to discuss criteria by which a plan of incentives for living donation could be judged to be acceptable. Conclusions were summarized, and outlined in a manuscript prepared by the participants and other interested parties [80••]. Four crucial elements were stipulated for an acceptable system: protection of the donor and recipient, regulation, oversight, and transparency. “Specifically, (i) the donor (or family) is respected as a person who is able to make choices in his or her best interest (autonomy); (ii) the potential donor (or family) is provided with appropriate information to support informed decision making (informed consent); (iii) donor health is promoted at every step, including evaluation and medical follow-up (respect for person); (iv) the live donor incentive should be of adequate value (and able to improve the donor's circumstances); (v) gratitude is expressed for the act of donation [80•• p 308].”

In terms of protection, the risk for living donors should be similar to the risk for currently accepted donors in the United States and other Western countries. In addition, in such a system, donors should benefit in a way that would improve their own or their family’s life: “For this to be acceptable, the donor must be fully informed, understand the risks, understand the nature of the incentive and how it will be distributed, and receive the benefit. There must be follow-up and an opportunity to address any wrong doing” [80•• p308]. In terms of regulation and oversight, all aspects of the process must be clearly defined for outside review (both national and international). Clearly defined policies must be established and implemented for follow-up, outcomes determination, and detection and correction of irregularities. Consequences must be defined for entities within the system that do not adhere to those policies.

In terms of transparency, it must exist throughout the process, so that both national and international observation is possible. Principles of an acceptable system have been formulated (Table 3), and guidelines for its development suggested (Table 4).

Tremendous debate continues about the value versus risk of such a system. As this debate goes on, the waiting list keeps growing longer. In the United States, more than 100,000 candidates are waitlisted for a kidney transplant alone (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network [OPTN] data accessed July 21, 2014). Since 1988, a total of about 119,000 transplant candidates have died while waiting; since 1999, currently, more than 6,000 transplant candidates have died each year while waiting. At the same time, more than 44,000 transplant candidates have been removed from the waiting list after becoming too sick while waiting even to be able to accept a graft.

Opponents to a regulated system argue that some countries would not be able to implement one, and therefore, any regulated system should be prohibited worldwide. The consequences of such a blanket prohibition are severe, including a shortage of organs, death of transplant candidates while waiting, disincentives to living donation, and development of underground, unregulated markets. No doubt, cultures — and the potential for successful regulation — vary between countries. But unregulated markets have developed even in countries prohibiting incentives for donation. At the same time, we have every reason to believe that countries in Western Europe, as well as Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States (and, likely, others) would all be able successfully to establish a regulated system as described above.

One way to assess the value of incentives would be to do clinical trials. To date, we have no data on outcomes after establishment of an acceptable regulated system of incentives. Proponents of incentives argue that a trial would determine whether or not any of the opponents’ concerns are realistic. The trial would have two major goals: (1) to determine whether donation rates increase and (2) to determine donor outcomes. If the trial were to show increased donation rates but poor donor outcomes (in terms of health, psychosocial or social issues, any regret) as compared with conventionally accepted donors, the system would be unacceptable. Without such a trial, the debate and discussion will go on endlessly, while potentially ideal transplant candidates deteriorate and often die while waiting.

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, the worldwide transplant community needs to take seriously the following realities: (1) the lack of effective regulation regarding living donation is dangerous to donors and recipients; (2) a significant number of transplant candidates are either dying while waiting or becoming too sick to transplant; and (3) experience has shown that unregulated, underground markets do not protect donors and recipients. Much of the debate about the potential value of a regulated system could be resolved by a clinical trial. Clearly, such a trial needs to be done in a country (or countries) that can develop acceptable systems, as defined by the principles outlined above.

If the government or its designated agency cannot provide full protection of both the donor and recipient, regulation, transparency, and oversight, then, at least in that country, a regulated system should not be considered. But in countries that have maximized conventional organ donation, continue to have a significant organ shortage and can meet the criteria outlined above, a clinical trial of incentives should be considered .

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Chamsi-Pasha H, Albar M. Kidney transplantation: ethical challenges in the Arab world. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2014;25(3):489–95. Discussion of some barriers to donations. Example of cultural differences.

Shimazono Y. The state of the international organ trade: a provisional picture based on integration of available information. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:955–62.

Budiani-Saberi D, Columb S. Care for commercial living donors: the experience of an NGO’s outreach in Egypt. Transpl Int. 2011;24(4):317–23.

Codreanu I, Codreanu N, Delmonico F. The long-term consequences of kidney donation in the victims of trafficking in human beings (VTHBS) for the purpose of organ removal. Transplantation. 2010;90(2S):214.

Mendoza RL. Colombia’s organ trade: evidence from Bogotá and Medellin. J Public Health. 2010;18(4):375–84.

Goyal M, Mehta RL, Schneiderman LJ, et al. Economic and health consequences of selling a kidney in India. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1589–93.

Moazam F, Zaman RM, Jafarey AM. Conversations with kidney vendors in Pakistan: an ethnographic study. Hastings Cent Rep. 2009;39(3):29–44.

Krishnan N, Cockwell P, Devulapally P, et al. Organ trafficking for live donor kidney transplantation in Indoasians resident in the west midlands: high activity and poor outcomes. Transplantation. 2010;89(12):1456–61.

Moniruzzaman M. ‘Living Cadavers’ in Bangladesh: ethics of the human organ bazaar. PhD, Toronto: University of Toronto.

Naqvi SAA, Rizvi SAH, Zafar MN, et al. Health status and renal function evaluation of kidney vendors: a report from Pakistan. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(7):1444–50.

Padilla BS. Regulated compensation for kidney donors in the Philippines. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(2):120–3.

Scheper-Hughes N. Keeping an eye on the global traffic in human organs. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1645–8.

Malakoutian T, Hakemi MS, Nassiri AA, et al. Socioeconomic status of Iranian living unrelated kidney donors: a multicenter study. Transplant Proc. 2007;29(4):824–5.

Scheper-Hughes N. The last commodity: post-human ethics, global (in)justice, and the traffic in organs. Dissenting Knowledges Pamphlet Series. Penang: Multiversity & Citizens International; 2008.

Ivanovski N, Masin J, Rambabova-Busljetic I, et al. The outcome of commercial kidney transplant tourism in Pakistan. Clin Transplant. 2010.

Alghamdi SA, Nabi ZG, Alkhafaji DM, et al. Transplant tourism outcome: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2010;90(2):184–8.

Salahudeen AK, Woods HF, Pingle A, et al. High mortality among recipients of bought living-unrelated donor kidneys. Lancet. 1990;336:725–8.

Budiani-Saberi DA, Rja KR, Findley KC, et al. Human trafficking for organ removal in India: a victim-centered, evidence-based report. Transplantation. 2014;97(4):380–4.

Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, et al. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors — a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1952–60.

McGrath P, Holewa H. ‘It’s a regional thing’: financial impact of renal transplantation on live donors. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:2144.

Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, et al. Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: a Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916–22. A prospective study of donor out-of-pocket costs in a country with universal health insurance.

Warren PH, Gifford KA, Hong BA, et al. Development of the national living donor assistance center: reducing financial disincentives to living organ donation. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(1):76–81.

Sickand M, Cuerden MS, Klarenbach SW, et al. Reimbursing live organ donors for incurred non-medical expenses: a global perspective on policies and programs. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2825–36.

Gill J, Dong J, Gill J. Population income and longitudinal trends in living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014.

Boyarsky BJ, Massie AB, Alejo JL, et al. Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2014. A single-center experience of post-donation difficulties obtaining insurance. Provides documentation supporting one of the disincentives to living donation.

Barnieh L, Klarenbach S, Gill JS, et al. Attitudes toward strategies to increase organ donation: views of the general public and health professionals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):1956–63. A recent survey on the public’s opinion on incentives for donation.

Bryce CL, Siminoff LA, Ubel PA, et al. Do incentives matter? Providing benefits to families of organ donors. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2999–3008.

Boulware LE, Troll MU, Wang NY, et al. Public attitudes toward incentives for organ donation: a national study of different racial/ethnic and income groups. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2774–85.

Danguilan RA, De Belen-Uriarte R, Jorge SL, et al. National survey of Filipinos on acceptance of incentivized organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(4):839–42.

Ghahramani N, Karparvar Z, Ghahramani M, et al. International survey of nephrologists’ perceptions and attitudes about rewards and compensations for kidney donation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(6):1610–21.

Guttman A, Guttman RD. Attitudes of healthcare professionals and the public towards the sale of kidneys for transplantation. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(3):148–53.

Hensley S, National Public Radio (NPR). Poll: Americans show support for compensation of organ donors. May 6 2012. Available at: http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/05/16/152498553/poll-americans-show-support-for-compensation-of-organ-donors. Accessed 21 Jul 2014.

Jasper JD, Nickerson CA, Hershey JC, et al. The public’s attitudes toward incentives for organ donation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:2181–4.

Kittur DS, Hogan MM, Thukral VK, et al. Incentives for organ donation? The United Network for Organ Sharing ad hoc donations committee. Lancet. 1991;338(8780):1441–3.

Mazaris EM, Crane JS, Warrens AN, et al. Attitudes toward live donor kidney transplantation and its commercialization. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E312–9.

Kranenburg L, Schram A, Zuidema W, et al. Public survey of financial incentives for kidney donation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):1039–42.

Leider S, Roth AE. Kidneys for sale: who disapproves, and why? Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1221–7.

Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Attitudes toward financial incentives, donor authorization, and presumed consent among next-of-kin who consented vs. refused organ donation. Transplantation. 2006;81:1249–56.

Haddow G. ‘Because you’re worth it?’: the taking and selling of transplantable organs. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:324–8.

Rodrigue JR, Crist K, Roberts JP, et al. Stimulus for organ donation: a survey of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons membership. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(9):2172–6.

Oz MC, Kherani AR, Rowe A, et al. How to improve organ donation: results of the ISHLT/FACT poll. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:389–410.

Siminoff LA, Mercer MB. Public policy, public opinion, and consent for organ donation. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2001;10:377–86.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Transplantation: 2012 National survey of organ donation attitudes and behaviors. Available at: http://organdonor.gov/dtcp/nationalsurveyorgandonation.pdf. Accessed 21 Jul 2014

The Wall Street Journal (Harris Interactive). Americans are divided on offering financial incentives to organ donors. 2007. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB117889765086700017. Accessed 21 Jul 2014.

Mauss M. The gift: the form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1990.

Valapour M, Kahn JP, Bailey RF, et al. Assessing elements of informed consent among living donors. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(2):185–90.

Fry-Revere S. The kidney sellers: a journey of discovery in Iran. Durham: Carolina Academic Press; 2014. An outsider’s description of the incentive system(s) in Iran. Important as there is controversy about the success of the Iranian system of incentives for donation.

Manauis MN, Pilar KA, Lesaca R, et al. A national program for nondirected kidney donation from living unrelated donors: the Philippine experience. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(7):2100–3.

Ghods AJ. Renal transplantation in Iran. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:222–8.

Ghods AJ. Governed financial incentives as an alternative to altruistic organ donation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2004;2(2):221–8.

Ghods AJ, Nasrollahzadeh D. Transplant tourism and the Iranian model of renal transplantation program: ethical considerations. Exp Clin Transplant. 2005;3(2):351–4.

Ghods AJ. Ethical issues and living unrelated donor kidney transplantation. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2009;3(4):183–91.

Ghods AJ. Without legalized living unrelated donor renal transplantation many patients die or suffer — is it ethical? In: Gutmann T, Daar AS, Sells RA, Land W, editors. Ethical, legal and social issues in organ transplantation. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2004. p. 337–41.

Moazam F. Bioethics and organ transplantation in a Muslim society: a study in culture, ethnography, and religion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2006.

Canales MT, Kasiske BL, Rosenberg ME. Transplant tourism: outcomes of United States residents who undergo kidney transplantation overseas. Transplantation. 2006;82(12):1658–61.

Gill J, Madhira BR, Gjertson D, et al. Transplant tourism in the United States: a single-center experience. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1820–8.

Ghods AJ, Ossareh S, Savaj S. Results of renal transplantation of the Hashemi Nejad Kidney Hospital. Tehran Clin Transpl. 2000; 203–10.

Ghods A, Savaj S. Iranian model of paid and regulated living-unrelated kidney donation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1136–45.

Zargooshi J. Iranian kidney donors: motivations and relations with recipients. J Urol. 2001;165(2):386–92.

Zargooshi J. Quality of life in Iranian kidney “donors”. J Urol. 2001;166(5):1790–9.

Radcliffe-Richards J. Nefarious goings on: kidney sales and moral arguments. J Med Philos. 1996;21:375–416.

Harris J, Erin C. An ethically defensible market in organs (Editorial). BMJ. 2002;325:114–5.

Gill MB, Sade RM. Paying for kidneys: the case against prohibition. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2002;12(1):17–45.

de Castro LD. Commodification and exploitation: arguments in favour of compensated organ donation. J Med Ethics. 2003;29(3):142–6.

Matas AJ. The case for living kidney sales: rationale, objections, and concerns. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(12):2007–17.

Kishore RR. Human organs, scarcities, and sale: morality revisited. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(6):362–5.

Taylor JS. Autonomy and organ sales, revisited. J Med Philos. 2009;34(6):632–48.

Daar AS. The case for a regulated system of living kidney sales. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2(11):600–1.

Hippen BE. In defense of a regulated market in kidneys from living vendors. J Med Philos. 2005;30:593–626.

Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, et al. Limiting financial disincentives in live organ donation: a rational solution to the kidney shortage. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(11):2548–55.

Matas AJ, Hippen B, Satel S. In defense of a regulated system of compensation for living donation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2008;13(4):379–85.

Radcliffe-Richards J. Paid legal organ donation, pro: the philosopher’s perspective. In: Gruessner RWG, Benedetti E, editors. Living donor organ transplantation. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. p. 88–94.

Goodwin M. Black markets: the supply and demand of body parts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Halpern SD, Raz A, Kohn R, et al. Regulated payments for living kidney donation: an empirical assessment of the ethical concerns. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(6):358–65.

Beard DL, Kasserman DL, Osterkamp R. The global organ shortage: economic causes, human consequences, policy responses. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2013.

Wilkinson S. Bodies for sale: ethics and exploitation in the human body trade. New York: Routledge; 2003.

Wilkinson TM. Ethics and the acquisition of organs. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Taylor JS, Simmerling MC. Donor Compensation without Exploitation. In: Satel S, editor. When altruism isn’t enough. Washington: AEI Press; 2008. p. 50–62.

Becker GS, Elias JJ. Introducing incentives in the market for live and cadaveric organ donations. J Econ Perspect. 2007;21(3):3–24.

Working Group on Incentives for Living Donation, Matas AJ, Satel S, et al. Incentives for organ donation: proposed standards for an internationally acceptable system. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):306–12. A consensus by an international group on the standards a country would have to meet to have an acceptable system of incentives for donation.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mary Knatterud, Rebecca Hays, and Hang McLaughlin for help in writing, editing and preparing this chapter.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Arthur J. Matas declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Live Kidney Donation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matas, A.J. The Rationale for Incentives for Living Donors: An International Perspective?. Curr Transpl Rep 2, 44–51 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-014-0045-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-014-0045-2