Abstract

Background

Heart failure presents a growing clinical and economic burden in the USA. Robust cost data on the burden of illness are critical to inform economic evaluations of new therapeutic interventions.

Objectives

This systematic literature review of heart failure-related costs in the USA aimed to assess the quality of the published evidence and provide a narrative synthesis of current data.

Methods

Four electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, EconLit, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination York Database, including the NHS Economic Evaluation Database and Health Technology Assessment Database) were searched for journal articles published between January 2014 and March 2020. The review, registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019134201), was restricted to cost-of-illness studies in adults with heart failure events in the USA.

Results

Eighty-seven studies were included, 41 of which allowed a comparison of cost estimates across studies. The annual median total medical costs for heart failure care were estimated at $24,383 per patient, with heart failure-specific hospitalizations driving costs (median $15,879 per patient). Analyses of subgroups revealed that heart failure-related costs are highly sensitive to individual patient characteristics (such as the presence of comorbidities and age) with large variations even within a subgroup. Additionally, differences in study design and a lack of standardized reporting limited the ability to compare cost estimates. The finding that costs are higher for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction compared with patients with preserved ejection fraction highlights the need for differentiating among different heart failure types.

Conclusions

The review underpins the conclusion drawn in earlier reviews, namely that hospitalization costs are the key driver of heart failure-related costs. Analyses of subgroups provide a clearer understanding of sources of heterogeneity in cost data. While current cost estimates provide useful indications of economic burden, understanding the nuances of the data is critical to support its application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a large amount of disparate data on medical costs due to heart failure (HF). To better inform cost analyses and economic evaluations, nuances of these data need to be better understood. |

This systematic review provides the most up-to-date overview of HF medical costs in the USA. It assesses the quality of the published evidence, synthesizes cost estimates, and characterizes the heterogeneity in HF costs. |

Analyses of subgroups provide a clearer understanding of the sources of cost heterogeneity (e.g., comorbidities, age, intervention, HF type). |

The review found that there was a paucity of data from perspectives other than the payer and the healthcare sector. |

The review underpins the conclusion drawn in earlier reviews, namely that hospitalization costs are the key driver of HF-related costs. |

The finding that costs are higher for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction compared with patients with preserved ejection fraction highlights the need for differentiating among different HF types in cost analyses. |

1 Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a global epidemic, affecting more than 64 million people worldwide [1]. In the USA, the estimated 2020 prevalence of HF is 6.9 million and is expected to increase by 24% to nearly 8.5 million in 2030 owing to the growth of the US population [2, 3]. Despite current standard of care, the clinical burden remains high. Approximately 30–40% of patients with HF have a history of hospitalization for HF [4, 5], which in turn is linked with worse outcomes. An analysis using data from the large US registry, Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure, linked to Medicare data, reported 5-year all-cause readmission (from index admission), readmission for HF, and mortality rates of 80.4%, 42.3%, and 75.4%, respectively [6].

The economic burden of HF on healthcare systems is considerable and will increase as the prevalence grows [7]. An analysis in 2012 estimated the cost of HF to be, globally, $108 billion per annum [8], with $65 billon attributed to direct costs and $43 billon to indirect costs [8]. In the USA, the total cost of care (direct and indirect costs) for HF in 2020 is estimated at $43.6 billion, with over 70% of costs attributed to medical costs [3]. Without improvements in outcomes, the annual total cost of care in the USA is projected to increase to $69.7 billion by 2030 [3].

As highlighted by Di Tanna et al., the cost of HF hospitalization is among the top reported model drivers in HF cost-effectiveness models [9]. They further suggested that the large uncertainty associated with HF hospitalization costs in the USA, even when focusing on just one jurisdiction, could be minimized with a systematic review of these costs and facilitate better informed economic models [10].

The primary aim of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to provide a qualitative assessment and narrative synthesis of the most up-to-date evidence on medical costs due to HF in the USA. As data on the medical costs associated with HF-related events vary greatly because of differences in study design [11, 12], adding significant complexity to understanding the cost burden, the secondary aim of this review was to understand the heterogeneity between the reported cost estimates. This synthesis of cost evidence can be used to support health technology assessment (HTA) submissions and economic evaluations of new therapeutic interventions that may improve clinical outcomes.

2 Methods

The literature review was conducted in accordance with a prespecified protocol, which was developed in line with methods recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) [13]. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019134201) and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14].

2.1 Search Strategy

Four electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, EconLit, and the CRD York Database, including the National Health Service Economics Evaluation Database and the HTA Database) were searched for journal articles published between January 2014 and March 2020. The search was restricted to studies reporting economic data on patients with HF in the US healthcare system, published in English in the last 6 years to ensure the most up-to-date cost evidence was captured and to increase the relevance of the findings. The MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EconLit databases were simultaneously searched by means of the ProQuest portal. Search strategies were developed individually for ProQuest and CRD, and the keywords adapted according to the configuration of each resource (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] 1 and 2).

The search strategy was developed based on preliminary reviews of background literature and expertise of the review team. It combined relevant search terms comprising indexed keywords (e.g., medical subject headings [MeSH]) and terms appearing in the title and/or abstract of database records. Search terms on the study design were based on the filters provided by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [15] and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health [16, 17].

Supplementary searches were undertaken in conference abstracts and other gray literature from 2016 until the date of search (March 2020), including the American Heart Association, Heart Failure Society of America, American College for Cardiology, American Society of Hematology, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, World Heart Congress, World Congress on Acute Heart Failure, International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, the International Health Economic Association, Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (global), and Research Papers in Economics. The references or citations of the retrieved articles were reviewed for additional articles (citation snowballing).

2.2 Selection Criteria

Studies were screened and selected if they reported cost of illness in adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with HF events in the USA. Studies in mixed populations (i.e., patients with HF and other conditions) were only included if costs relating to a HF event were reported separately. Budget impact analyses, cost-effectiveness studies, and HTA submissions were excluded. However, the original sources of cost inputs from these publications were checked to ensure no relevant (original) studies were missed by the search strategy. In case an economic model study used a de-novo input (for instance, a hospitalization cost from internal sources), the paper was included in the review and considered a primary study. Likewise, systematic reviews and meta-analyses were retrieved only for reference screening.

2.3 Data Extraction

Data were extracted into a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Data were extracted on study characteristics, study methods, and cost outcomes. The study selection process and data extraction were performed by one reviewer with a second reviewer conducting an independent quality check of the data. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

2.4 Quality Criteria

The quality of studies identified in the literature search is discussed based on three criteria: use of appropriate costing methodology (based on a reporting checklist), clearly provided HF-attributable costs, and subgroup cost analyses.

2.4.1 Use of Appropriate Costing Methodology

To assess the costing methodology, a shortened version of the Drummond et al. checklist used by the British Medical Journal to assess economic evaluations was used [18]. This shortened checklist was modified to cover the following: (1) study design: whether the objectives of the study were clearly reported and the economic perspective (i.e., who bears the costs) was reported and justified; (2) data collection: whether the resource use and unit cost data collection was reported; and (3) analysis and interpretation of results: how results were analyzed and interpreted by the authors.

2.4.2 Clearly Provided Heart Failure-Attributable Costs

Heart failure is associated with older age and often occurs in patients with other comorbidities. Such patients are therefore likely to require additional healthcare resources that are unrelated to HF. To avoid overestimating costs, a costing study should include, and clearly state, those costs that are specifically attributable to HF. In addition, HF may induce or aggravate non-related conditions. Therefore, when allowed by the studied samples, studies should compare resource use with and without HF, instead of only reporting all-cause resource use.

2.4.3 Subgroup Cost Analyses

Heart failure populations are diverse, and costs of HF vary substantially between individuals, depending on characteristics such as disease severity, subtype, etiology, age, sex, and comorbidity. Therefore, if feasible, studies should report the costs of HF events according to patient characteristics, event subtype/severity, and etiology. Studies that included subgroup analyses were reviewed to better understand sources of cost heterogeneity.

2.5 Analysis of Cost Estimates

Studies that reported the cost year were included in a comparison and analysis of cost estimates. All costs reported were inflated to 2019 US$ based on the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index, acquired from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [19]. Medical costs refer to the cost of production of healthcare services. They were categorized as total medical costs, HF-specific hospitalization costs, post-discharge costs, readmission costs, outpatient care costs, and other medical costs, and reviewed descriptively. Categorization was based on the cost data description provided in the primary publications. For full transparency, median and interquartile limits (IQL), as well as arithmetic mean and range, were calculated when possible for each group of cost estimates, thereby acknowledging the skewed nature of the cost distributions.

As reductions in the risk of morbidity and mortality as a result of therapy have only been demonstrated in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [20], studies reporting specifically on costs related to HFrEF are highlighted. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, also referred to as systolic HF, is defined by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines as the clinical diagnosis of HF and left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 40% [21]. Understanding the economic impact, as well as clinical impact, of such therapies is critical to support their appropriate utilization.

3 Results

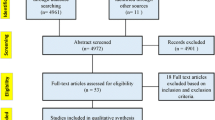

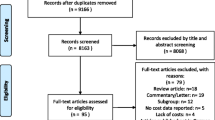

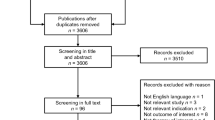

The literature searches retrieved a total of 1480 titles and abstracts (after de-duplication). After screening, 221 references were selected for full-paper screening. After a subsequent detailed review, 81 references were selected as meeting all the inclusion criteria; ESM 7 lists the 140 publications that were excluded after full-paper screening. Nine additional studies were derived from gray literature and citation snowballing. Three of the included studies were each reported in two references (i.e., a conference abstract and a full-text publication). This brought the total to 87 included studies (90 individual references) for data extraction. Figure 1 presents a summary of the searching, screening, and inclusion assessment process in accordance with the PRISMA checklist [14].

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart displaying the number of publications included as well as the number of publications that were excluded, with reasons. CRD Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, HF heart failure, HTA health technology assessment, NHS EED NHS Economic Evaluation Database, SLR systematic literature review

The 87 included studies are summarized in the following section. The studies are described according to the three quality criteria detailed in the Methods section. A complete list of all the studies and their methods are given in ESM 3 (study characteristics) and ESM 4 (applied definition of HF). The results per study are presented in ESM 5.

3.1 Study Population and Design

The majority of the studies (n = 69; 79%) assessed the costs associated with HF-related events among exclusively patients with HF, with some defining in more detail the type of HF (n = 28; 32%) [ESM 3, column ‘population’] [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. The majority of studies (n = 55; 63%) defined the population by the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes (ESM 4). Eight articles referred to both ICD-9 and International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), while 32 did not specify the ICD classification (12 used different definitions, 20 did not provide details of definition). The study population sizes had a range from 135 [50] to 11,723,008 [51]. The mean age of the study populations varied from 59 to 84 years.

The majority of studies were retrospective cohort studies (77/87; 89%), and analyses were based on varied healthcare databases (55/77 studies), six of which explicitly referred to as ‘medical records’ and/or ‘chart reviews’ in the studies, administrative claims data (20/77), registry data (1/77), or combined medical records and claims data (1/77) [ESM 3]. Five studies (5/87) used an economic model populated with data from different healthcare databases [45, 52,53,54,55,56]. A cross-sectional design, where costs were assessed at a discrete point in time, was adopted by three studies [57,58,59]. The remaining two studies used information generated alongside a randomized controlled trial [33, 46]. The vast majority were multi-centered studies (74/87; 85%) using data from inpatient settings (n = 41), while 33 studies combined inpatient and outpatient settings.

The perspective of cost analysis was not clearly stated in most of the studies (67/87; 77%). Thus, the perspective of analysis was often based on the researchers’ interpretation of the data. In 40 (45%) studies [22,23,24, 44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 53, 55, 57, 58, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86], costs for HF-related events were (or appeared to have been) analyzed from a payer’s perspective. Three studies adopted a healthcare sector perspective [87,88,89]. Only two studies adopted the societal perspective [25, 59], one study adopted the viewpoint of the patient [43], and one the hospital perspective [45]. The remaining 40 studies (only published as abstracts) left the perspective undefined entirely.

The method of estimating costs was not explicitly stated in the majority of studies (58/87; 67%) (ESM 3). Based on the reviewers’ interpretation, 41 studies employed a bottom-up approach (cost profile is constructed using disaggregated patient-level data), seven used a top-down approach [47, 64, 65, 71, 74, 76, 90] (total expenditure divided by number of patients treated), and one study [25] used a mixed costing method. Information reported by the remaining studies (n = 38, only published as abstracts) did not allow for conclusions to be drawn on the costing approach.

The earliest cost year used in the studies was 2009 [24], with the latest cost year being 2017 [57]. Forty-four studies did not report a price year for cost estimates.

3.2 Cost Categories

The 87 studies were reviewed and costs assigned to the most appropriate cost category, as per Drummond et al. (Table 1) [91]. The majority of studies (85/87; 98%) included hospital inpatient care costs. A sizable proportion of studies reported outpatient care (also known as ambulatory care) costs (36/87; 41%); this included costs for emergency department services, primary care physician office visits, and pharmacy costs. Costs for home care or nursing home/skilled nursing facility were only included by six (7%) studies. Only four studies reported out-of-pocket costs, while none included travel costs or social benefits. Patients’ productivity losses were not reported. One study reported costs of informal caregivers [59].

3.3 Subgroup Analyses

The studies were furthermore reviewed for subgroup analyses. In total, 48 (55%) studies presented costs for different patient subgroups, of which 12 performed a multivariable analysis to assess predictors of costs. Table 2 lists the different subgroups analyzed across the 48 studies.

3.4 Sources of Heterogeneity

The annual medical costs associated with HF varied greatly because of the presence of comorbidity with a range from $19,537 for patients with HF with hypertension to $77,214 for patients with HF with hyperkalemia [58, 73, 89]. Likewise, the cost of HF hospitalization had a range from $8702 in patients with depression to $40,407 in patients with protein-energy malnutrition [58, 60]. The cost estimates for each comorbidity-related subgroup are presented in ESM 5. The age subgroup analyses showed that the cost of hospitalization was 5–31% higher for patients with HF aged < 65 years than those aged ≥ 65 years [62, 63, 65, 67, 74, 92].

The subgroup analyses across different types of patients with HF showed that the cost per hospitalization episode for patients with HFrEF was 13–100% higher compared with the cost for patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [23, 25, 77, 115]. One study investigated costs of chronic vs acute HF, based on cost per discharge, demonstrating higher costs with chronic disease ($17,771 vs 13,976, in 2019 US$) [25].

The cost of HF hospitalization varied per hospital ownership with higher cost in not-for-profit hospitals, followed by government and for-profit hospitals; however, total charge billed was highest in for-profit hospitals and lowest in government hospitals [63]. Among patients with a liver transplant experiencing a HF event, the HF-related treatment in a transplant center was more costly than the care provided in a non-transplant hospital [22]. The authors concluded that this may be related to selective referral of certain patient phenotypes to transplant centers. Similarly, increased mean hospital charges and length of stay was found for patients with HF with a history of hematopoietic stem cell transplant admitted in teaching hospitals (as compared with non-teaching hospitals) [94].

Subgroup cost analyses per US region, type of hospital admission, and health plan type were each reported by single studies. A review of the data revealed there is regional variation in the cost of HF hospitalization, with higher costs in the West ($9908 per patient) and Northeast ($9022) compared with other regions of the country (Midwest: $8021; South: $7089) [62].

The study by Obi et al. [87] compared annual total medical costs between patients with HF who died to those who survived (stratified by health plan type). Authors found that patients who died incurred substantially higher costs from index to death, as compared with survivors, despite the mean post-index period being 59% shorter compared with survivors (matched cohorts). This trend was observed regardless of health plan type; however, the difference in cost between decedents and survivors was greater for those with commercial plans (2.6-fold higher) than those with Medicare Advantage with Part D plans (1.5-fold higher). The findings from this study offer useful insights on the end-of-life cost burden in patients with HF.

Last, the study by Punekar et al. [88] evaluated total medical costs associated with HF events in patents with hyperlipidemia, per baseline risk of cardiovascular (CV) disease (high risk, primary prevention, secondary prevention), and the number of HF events (only one, two, or three HF events) over a 2-year follow-up. Authors found that the total medical costs were higher among cases (patients with a CV event) compared with controls (patients without a CV event) in all three cohorts, and costs remained higher throughout the follow-up period for HF events. Mean 2-year total costs among patients with only one HF event and only two HF events were highest for the primary prevention cohort ($75,229 and $106,595, respectively) compared with the secondary prevention ($65,649 and $76,760) and high-risk ($65,010 and $90,246) cohorts. Mean 2-year total costs among patients with only three HF events were highest for the high-risk cohort ($108,319) compared with the primary prevention cohort ($104,347) and secondary prevention cohort ($94,548).

3.5 Heart Failure-Related Costs vs All-Cause Costs

Studies were assessed to determine whether published costs were HF related or all cause. Seventy-two (83%) studies estimated costs only attributable to HF events (n = 68), or separate cost estimates were provided for all-cause and HF-related resource use (n = 4) [44, 65, 85, 87]. In the remaining 15 studies, eight (53%) assessed the costs that could be directly attributed to HF by comparing the costs of patients with HF to those with no HF [51, 69, 88, 95, 104, 105, 107, 111]. In the other seven studies [46, 58, 66, 68, 75, 89, 94], it was inferred that all-cause resource use (i.e., no distinction for HF-related resource use) had been included in the analysis.

3.6 Comparable Cost Estimates

Comparable cost estimates are summarized in Table 3. Forty-three studies identified from the SLR included a cost year and could be inflated to 2019 US$. Two of these, however, were excluded from the summary of comparable cost estimates because one study reported only informal caregiving costs [59], while in the other study, patients were identified by the index event of a pharmacy claim rather than an HF event [43]. The 41 remaining studies included in the summary of comparable cost estimates, along with the study-specific cost/price years and the original values are detailed in ESM 5. All studies considered the economic burden of patients with HF in terms of direct medical costs due to inpatient care, outpatient care, and/or medications. Of the 41 studies, 24 only included patients who had been hospitalized for HF, and the remaining 17 included a mix of hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. The reported costs were subject to large variations, which was, in part, owing to how the cost components were defined in the individual studies or how the resource use was valued, i.e., charges vs costs. Charges refer to the initial individual list prices a US hospital typically sets for the services it provides. They are usually higher than costs, which are the actual expenses incurred by a hospital in providing patient care (including the direct costs of patient care such as nursing, room and board, medicines and supplies; as well as overhead costs for administration).

3.6.1 Total Medical Heart Failure-Related Costs

The annual median medical costs for HF care was $24,383 (IQL $20,713–$40,619) per patient (Table 3). Reported charges were substantially higher than reported costs (mean $98,599) and increased to > $100,000 per patient with HF when all-cause readmissions were included in the cost estimation [65].

Costs varied with the presence of a comorbidity and with survival. Analyzing the comparable costs by subgroup with a specified comorbidity, the estimated median annual total medical cost was $46,580 (IQL $39,585–$64,664) per patient, almost double the cost estimated for the general HF population ($24,383) (Table 3). The actual reported costs/charges varied greatly with the specified comorbidity. The cost estimates for each patient subgroup are presented in ESM 5.

One study analyzed costs according to survival [87]. The medical cost per patient accrued within 30 days from the date of the earliest qualifying claim with a diagnosis code for HF varied from $1592 for patients who survived to $19,317 for patients who died. Patients with HF who died within 1 year after an index HF encounter incurred markedly higher per-patient-per-month costs than patients in the survivor cohort, with the majority of costs attributable to hospitalizations for both patient cohorts. Likewise, the all-cause medical cost (including inpatient care, outpatient care, and pharmacy costs) for the same population had a range from $3510 (HF survivors) to $25,510 (HF decedents) per patient per month [87].

3.6.2 Heart Failure-Specific Hospitalization

The median cost for a HF-specific hospitalization was $13,418 (IQL $11,125–$15,667) per patient (Table 3). For patients with co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease), the median HF-specific hospitalization cost was slightly higher, at $14,015 per patient (IQL $11,769–$20,373).

Olchanski et al. [77] estimated mean hospitalization costs by category, stratified by diabetes status and HF subtypes (HFrEF and HFpEF). Mean hospitalization costs were higher for patients with diabetes regardless of HFrEF ($16,679) vs HFpEF ($15,301) status at admission compared with those without diabetes (HFrEF, $12,296; HFpEF, $11,828). The authors also reported on the following subcategories: diagnostic tests (range $933–$1197 per patient), room and board expenses ($4110–$6188), therapies ($339–$753), pharmacy ($445–$729), other expenses ($1144–$1364), and total cost per day alive ($3022–$11,828). Patients with HFrEF had 4–9% higher hospitalization costs compared with patients with HFpEF. Room and board expenses were 12–16% higher for patients with HFpEF compared with patients with HFpEF. Similarly, diagnostic and pharmacy costs were 6% and 23% higher for patients with HFpEF, respectively. Therapy costs were 19–31% higher for patients with HFpEF compared with patients with HFrEF. Last, cost per day alive for patients with HFpEF exceeded corresponding costs for patients with HFpEF by 5–10%. The annual median cost for HF-specific hospitalizations was $15,879 (IQL $9444–$20,933) per patient and for all-cause hospitalizations $20,826 (IQL $18,779–$29,045) per patient.

3.6.3 Post-Discharge Cost

Two studies estimated the average post-discharge cost following a HF hospitalization event [57, 97]. The average 30-day post-discharge cost following a worsening HF admission was estimated at $6283 per patient [57]. It was calculated as the difference between all costs incurred in the 30 days following discharge and the average 1-month cost of a patient with HF [57]. Raju et al. [97] estimated the monthly HF-related post-discharge costs at $1771 per patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and at $1543 per patient without T2DM. The monthly all-cause post-discharge costs were estimated at $8722 and $8055, respectively.

3.6.4 Readmission Cost

One study estimated the cost associated with readmissions for patients discharged following a HF hospitalization [67]. Lahewala et al. [67] estimated the mean cost of care of readmission over a 30-day period after HF hospitalization in the same hospital at $15,732 per patient and in a different hospital at $25,879 per patient (the associated mean length of stay per patient was 6.1 and 7.5 days, respectively).

Another study evaluated costs for patients with hyperlipidemia with one, two, or three HF hospitalization events [88]. The associated mean 2-year costFootnote 1 range was from $65,010 to $75,229 (one HF event), $76,760–$106,595 (two HF events), and $94,548–$108,319 (three HF events), respectively, depending on pre-index clinical characteristics of the patients (high risk, primary prevention, or secondary prevention). A third study estimated the cost of 30-day all-cause readmission for patients discharged following a HF hospitalization at $7583 [53].

3.6.5 Outpatient Care Cost

Most of the included studies captured costs for outpatient medication and physician visits within the total medical cost estimated; only seven studies itemized outpatient visit costs separately from other medical costs [25, 34, 46, 57, 64, 76, 86], which had a range from $297 [86] to $3859 [64] per patient. Yoon et al. [76] estimated the annual average cost per patient per type of outpatient healthcare, including medical/surgical costs ($8487), diagnostic costs ($2178), behavioral costs ($550), other costs ($973), and pharmacy costs ($2904).

Six studies reported the cost of the emergency department services [24, 25, 55, 57, 58, 64]. The median cost per visit was $1441 (IQL $829–$1933). A seventh study estimated the annual HF-related emergency service cost at $212–$291 per patient, averaged over a cohort of 1-year survivors and 1-year decedents post-index HF claim, respectively [87]. Per-patient estimates reflecting only those patients who did visit the emergency department were not provided. The same study estimated the annual average HF-related ambulatory costs at $930 and $1902 per patient among patients with HF who died and those who survived, respectively. The respective cost estimates per patient per month were $18–$93 and $156–$192 for HF-related emergency and ambulatory services, respectively [87].

3.6.6 Other Medical Costs

The economic burden of home healthcare was estimated only by Echouffo-Tcheugui et al. at $2227 per patient per year [64]. The same study provided an average annual cost estimate of $813 per patient, for a list of services including nursing home, rehabilitation, vision, medical supplies, and dental services. The study reported cross-sectionally on patients with a HF diagnosis (10-year inclusion window), with no requirements for hospital admission.

3.6.7 Costs for Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

Five studies reported costs for patients with HFrEF [23, 25, 34, 44, 77]. The median HF-specific hospitalization cost (including room and board, diagnostics, therapies, pharmacy, emergency department, and overhead costs) was $12,915 (IQL $12,156–$13,664) per stay [23, 25, 77]. One study estimated the mean HF-specific hospitalization cost at $12,915 in patients with T2DM and at $10,103 in patients without T2DM [77]. The same study further estimated the total cost per day of HF-specific hospital stay at $2205 and $2115 in patients with T2DM and without T2DM, respectively.

Two studies estimated charges (rather than costs) for HF-related care [34, 44]. Givertz et al. looked at HFrEF in patients who had been hospitalized and/or required intravenous diuretic because of worsening HF (0.7 hospitalizations per person during the first 30 days after HF onset). The mean medical charges (including dispensed prescriptions and number of private healthcare and hospital-facility visits) accrued within the first 30 days following the event were $31,300; monthly mean charges for the remaining year was $32,524 per patient [34]. Bress et al. [44] assessed resource utilization and associated charges among a real-world cohort of patients with HFrEF in an academic medical center setting. The median hospital charges for an all-cause, HF-specific, and 30-day all-cause readmissions were $25,545, $26,393, and $31,503, respectively. Index hospitalizations were included in the charge analysis. Cost estimates specific to other types of HF (with preserved ejection fraction [diastolic HF]; acute decompensated HF) were reported in five studies [23,24,25, 49, 72].

3.7 Quality Assessment

The quality of this review is in part limited by the quality of the identified studies. The studies that do not report the cost year of the provided estimates were considered of insufficient quality and were excluded from further quality assessment. Therefore, quality assessment is provided for 43 studies.

Only studies that reported a cost/price year were included in a comparison and analysis of cost estimates. All studies included in the analysis of comparable costs met the quality criteria for economic evaluations as used by the British Medical Journal [18] and were therefore concluded to be of high quality. An overview of adherence of the studies to each of the items used for the quality assessment is presented in Fig. 2.

All the studies that were subject to the quality assessment (n = 43) clearly stated the research question and defined the target population. The study setting (inpatient/outpatient) and location was well reported in all but one study [59].

The perspective of the economic analysis was adequately reported and justified in 19 studies (44%); less than half (21/43; 40%) [22, 24, 25, 44, 46, 47, 49, 53, 59, 60, 63, 65, 67,68,69, 74, 81, 87,88,89, 116] did not clearly define the perspective but the available information allowed for interpretation in line with published definitions [117]; three studies (10%), only published as abstracts, left the perspective completely undefined [34, 90, 97].

Sources of resource use and unit costs, currency and cost year, and the methods of resource use valuation (i.e., cost/charge, cost-to-charge ratio) were well defined in all studies. The majority of studies (26/43; 60%) reported adequately on the methodology of estimating costs [22,23,24, 43, 44, 49, 50, 57,58,59,60, 63, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72, 75,76,77, 85, 87, 88, 116]; in 14 (33%), the costing approach was concluded by the information reported and relevant guidelines by Drummond et al. [91], although not explicitly stated [25, 45,46,47, 53,54,55, 64, 65, 81, 86, 89, 90, 118]; three studies (10%), only published as abstracts, did not provide any information on the costing methodology [34, 73, 97].

Time horizon was reported by 38 studies, with the majority (33/43; 77%) estimating costs over a relatively short time frame of up to 1 year. Only five studies estimated the costs for a HF event for a period greater than 1 year [44, 46, 71, 75, 88], and only one of them discounted costs incurred after the first year. Time horizon was not applicable for the remaining five economic model studies, from which only de-novo cost inputs were extracted [45, 53,54,55, 74]. In all the studies, the answer to the study question was given, conclusions followed from the data reported, and in all but six studies (14%, only published as abstracts) [34, 49, 73, 86, 90, 97] the conclusions were accompanied by the appropriate caveats.

4 Discussion

This SLR provides a current assessment of medical costs due to HF-related events in the USA, capturing data published from 2014 to 2020. It is the first effort to systematically appraise costs in patients with HF. While the SLR identified 87 studies reporting cost data, there was a large variation in study design and reporting detail. Only 43 studies provided sufficient data to enable inflation to 2019 US$ and 41 of them allowed a comparison of cost estimates (Table 3). The majority of studies were retrospective database analyses.

Hospitalization because of acute decompensation is a common outcome in patients with HF. All 43 studies included in the detailed cost review captured hospitalizations as part of their cost estimates. This review showed that hospitalization is the major contributor to the overall direct costs for HF; based on median data, HF hospitalization costs make up 65% of all medical HF costs over a 1-year treatment period from the index hospitalization event. This is in agreement with a recently published review that showed that the costs for hospitalization account for 44–96% of the overall direct costs for HF [11]. Owing to the dominance of hospitalization in HF costs, highlighted in this and other studies, it is not surprising that hospitalization is among the first reported outcomes and the common driver in HF cost-effectiveness models [9, 10].

Of note, several studies focus on group-level comparisons and therefore the estimates for hospitalization costs appear to reflect per-patient averages, including patients who were not hospitalized [24, 29, 34, 44, 50, 76, 87]. Bress et al., Givertz et al., and Yoon et al. report per-patient numbers of hospitalizations of 0.5, 0.7, and 0.83 (medical/surgical stays) over varying periods of time [34, 44, 76]. Storrow et al. report on patients that entered the emergency department, with 83.7% leading to admission [24, 34]. However, being charges rather than costs, the estimates reported by Bress et al., Givertz et al., and Storrow et al. were not taken into account by the authors of this review when calculating the overall HF-specific hospitalization cost (Table 3) [24, 34, 44]. Last, Fitch et al., Jackson et al., and Voigt et al. concern samples of patients who were not per se hospitalized,Footnote 2 but the cost estimates appeared to reflect only hospitalized patients [25, 57, 58].

Following initial HF hospitalization, all-cause readmission rates are high, with approximately 20% of patients being readmitted within 30 days, further driving medical costs and poor outcomes [119,120,121]. Annual medical charges for patients with HF, including all-cause readmissions exceed > 185,000 US$ (2018), of which nearly half were due to non-HF readmissions [65]. The consideration of readmission rates (both HF specific and all cause) should be an important factor when building a cost-of-illness profile for patients hospitalized for HF, and when developing economic evaluations. Steps to reduce readmission would not only improve patient outcomes but also reduce both direct costs and readmission penalties, imposed on hospitals by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for higher readmissions rates than expected [122]. The high economic burden of readmissions of patients with HF is well acknowledged, and reducing readmissions may provide large cost savings [123, 124].

Previous studies highlight the wide variation in HF costs [11, 12, 125], an observation that was also noted in this review. As a second objective, this study also sought to characterize the heterogeneity in HF costs. Reporting costs due to HF, without taking into account the impact of some of these sources of heterogeneity, may limit the usefulness of the data when assessing the cost effectiveness of HF interventions. Of the 87 studies identified in the literature review, 48 provided cost data for patient subgroups or predictors of costs. Of these studies, HF costs according to comorbidities, intervention, age, and type of HF were most commonly studied. However, heterogeneity due to other factors such as the number of HF events, CV risk level, US region, health plan type, and type of hospital admission were not so well studied, calling for further research in these areas. Conclusive research findings solely on the basis of a single study is likely to be less credible, as their representativeness and generalizability to other settings may be limited [126].

While a review of subgroup analyses did provide a clearer understanding of sources of cost heterogeneity, what also became evident is how variable cost data are even within subgroups. For example, depending on the specific comorbidity, HF hospitalization costs varied by nearly five-fold [58, 60] and total medical costs over 1 year by nearly four-fold [73, 89]. Surprisingly, younger patients (aged < 65 years) were associated with higher costs than older patients (aged ≥ 65 years); the cost increase range was 5–31% [62, 63, 65, 67, 74, 92]. The lower costs among the older patients may reflect a higher rate of mortality, which affects both the number of admissions and the length of hospital stay of older patients. Heart failure hospitalization costs were higher for patients with HFrEF, compared with patients with HFpEF, even though patients with HFpEF were older and had more comorbid conditions; the cost increase range was 13–100% [23, 25, 77, 115]. Costs were largely driven by the length of stay, with a higher heart rate at admission, lower systolic blood pressure, and higher creatinine associated with higher inpatient costs [23, 25, 77, 115]. These findings are consistent with a recently published cohort study indicating higher costs for patients with HFrEF than for patients with HFpEF over a 2-year follow-up period [127]. These data highlight how sensitive cost data are to individual patient characteristics. Because of a lack of cost estimates among the reviewed studies, this review falls short of providing an assessment of the impact of disease severity, for instance, as measured by the New York Heart Association classification, on HF-related costs. While fully capturing or adjusting for these variables in economic evaluations is likely to be virtually impossible, understanding the limitations of cost estimates in terms of variation is important when using the data.

Another gap identified during this review was the paucity of data from perspectives other than the payer and the healthcare sector. Only four of the total 87 studies provided societal, patient, or hospital cost perspectives of HF events [25, 43, 45, 59]. Social care costs are an important element of longer term care for patients with debilitating events. Absenteeism, presenteeism, and informal care are related to considerable indirect costs (i.e., non-medical costs comprising resources that support the provision of healthcare services). It is estimated that the total loss of earnings attributed to HF morbidity and mortality will be $12.4 billion in 2020 in the USA [3]. Furthermore, approximately one in three patients with HF require informal care averaging at 45 h per week [128]. Joo et al. reported an average annual cost of informal caregiving of $836 per patient [59]. Focusing only on the payer perspective obscures our understanding of disease burden on patients and their families. A part of HTAs is to ensure equity in allocation of resources. Therefore, cost reviews and economic models adopting a societal perspective should consider the indirect costs in addition to the direct costs related to HF events.

The majority of studies reported costs over a short time horizon. Only five studies estimated the costs for a HF event for a period greater than 1 year [44, 46, 71, 75, 88]. Punekar et al. [88] and Mark et al. [46] estimated total medical costs associated with HF event(s) over a 2-year follow-up (i.e., year 1 and 2), Henk et al. [75] reported similar costs over 1, 2, and 3 years separately, and Ward et al. [71] estimated the cost per patient reflecting annual resource use required beyond the first year for the ongoing management of the HF complication, which applies while that particular health state is present for the remainder of the patient’s life (ESM 6). Last, Bress et al. [44] estimated HF hospitalization charges (rather than costs) among patients with HFrEF over a 2-year follow-up. The short time horizons in the majority of studies might explain why 45–87% of overall HF costs were attributable to initial hospitalization costs alone [34, 71, 76, 87]. This also highlights the need for more long-term studies, and a clearer understanding of ambulatory costs to determine the lifetime costs of HF.

To minimize bias, studies were assessed to determine if costs were directly attributable to or associated with HF. In the majority of studies, the costs were attributable to an HF event. Heart failure-specific costs were sometimes reported either alongside or instead of total costs [75, 88, 95]. Some studies used a matched cohort method to attribute costs specifically to a HF event as opposed to those that might have been incurred without the HF event. This method allowed the assessment of costs over and above what might have been experienced by patients with similar characteristics [69, 73, 75, 87, 88, 95].

Like other reviews of cost outcomes, comparison of cost data in this review was substantially limited because of unstandardized reporting. For example, a breakdown of the cost estimates in terms of the cost components was sometimes missing or poorly reported. Furthermore, variability in study design made it difficult to compare event costs, as well as contributing to data heterogeneity. This included the duration of follow-up or the method of estimating costs. Standardized approaches to conducting and reporting cost data would reduce this data heterogeneity and enable better cost comparisons between studies.

Finally, because of poor and unstandardized reporting, a review of the studies involved some subjective interpretation, leading to potential bias. The wide variation in the definition and terminology used to describe the cost components across studies, for example, required the cost estimates to be grouped under broadly comparable headings (total medical costs, HF-specific hospitalization cost, post-discharge cost, readmission cost, outpatient care cost, and other medical cost) based on the reviewers’ interpretation of the data. The perspective of the cost analysis and methods of estimating costs were also frequently subject to reviewer interpretation.

Our review aimed to provide HF-related costs in the USA. Therefore, the absolute cost estimates cannot be transferred to other jurisdictions with different systems of healthcare delivery. However, the findings on the main contributors to overall direct costs for HF, such as hospitalizations and readmission rates, along with the presence of comorbidity, are expected to be more generalizable.

5 Conclusions

Heart failure is a growing clinical and economic burden. This systematic review provides the most up-to-date overview of HF medical costs in the USA. For the purpose of economic evaluations, the current study assessed the quality of the published evidence and synthesized cost estimates. It underpins the conclusion drawn in earlier reviews, namely that hospitalization costs are the key driver of HF-related costs. However, there is a considerable degree of heterogeneity in published HF costs, owing in part to specific medical needs of different patient subgroups. Another source of heterogeneity is variation in study design and reporting, which also hinders cost comparisons. There is a large amount of disparate data on medical costs as a result of HF; however, to better inform cost analyses, the nuances of these data need to be better understood. This could be achieved through improved and standardized reporting of data.

Notes

Heart failure total cost includes inpatient care, outpatient care, and pharmacy costs for all medical events during the follow-up period (i.e., 2 years).

Eligibility of patients in the study was based on HF diagnosis, not HF admission/hospitalization.

References

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32279-7.

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):E67–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558.

Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–19. https://doi.org/10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a.

Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(6):613–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.566.

Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, Duffy CI, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.070.

Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(20):2476–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Savarese G, Lund LH. Global public health burden of Heart Failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3(1):7–11. https://doi.org/10.15420/cfr.2016:25:2.

Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171(3):368–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.028.

Di Tanna GL, Chen S, Bychenkova A, Wirtz HS, Burrows KL, Globe G. Economic evaluations of pharmacological treatments in heart failure patients: a methodological review with a focus on key model drivers. Pharmacoecon Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-00173-y.

Di Tanna GL, Bychenkova A, O’Neill F, Wirtz HS, Miller P, Hartaigh BO, et al. Evaluating cost-effectiveness models for pharmacologic interventions in adults with heart failure: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(3):359–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0755-x.

Lesyuk W, Kriza C, Kolominsky-Rabas P. Cost-of-illness studies in heart failure: a systematic review 2004-2016. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-018-0815-3.

Liao L, Allen LA, Whellan DJ. Economic burden of heart failure in the elderly. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(6):447–62. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826060-00001.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009.

LA Moher D, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Scottisch Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN search filters 2015. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/search-filters.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

Glanville J, Fleetwood K, Yellowlees A, Kaunelis D, Mensinkai S. Development and testing of search filters to identify economic evaluations in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Strings attached: CADTH database search filters. Ottawa: CADTH; 2016. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/strings-attached-cadths-database-search-filters. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

Drummond MFJT. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ: the BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers: medical care in U.S. city average. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIMEDSL. Accessed 23 Apr 2020.

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019.

Khurmi NS, Chang Y-H, Eric Steidley D, Singer AL, Hewitt WR, Reddy KS, et al. Hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease after liver transplantation in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1398–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25055.

Olchanski N, Vest AR, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, DeNofrio D. Cost comparison across heart failure patients with reduced and preserved ejection fractions: analyses of inpatient decompensated heart failure admissions. Int J Cardiol. 2018;261:103–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.024.

Storrow AB, Jenkins CA, Self WH, Alexander PT, Barrett TW, Han JH, et al. The burden of acute heart failure on U.S. emergency departments. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(3):269–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.01.006.

Voigt J, Sasha JM, Taylor A, Krucoff M, Reynolds MR, Gibson MC. A reevaluation of the costs of heart failure and its implications for allocation of health resources in the united states. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37(5):312–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22260.

Afzal A, Nisar T, Kluger A, Jamil A, Felius J, Hall SA, et al. National trends in systolic and diastolic heart failure from 2004 to 2014. Circulation. 2018;138:A17241.

Ahsan SA, Dehkordi SHH, Gholitabar F, Lee S, Lemor A, Gholitabar N, et al. Decreasing mortality and hospital costs: trends in congestive heart failure exacerbation admissions from 2004 to 2014. Circulation. 2017;136:A20946.

Al Emam ARA, Khattab B, Chamsi-Pasha M, Vongooru H. Changes in outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute on chronic diastolic heart failure in the United States over the last decade. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1465.

Albert N, Swindle J, Buysman E, Chang C. Reduction in hospitalization and medical costs among patients initiated with sacubitril/valsartan: insights from an administrative database in the united states. J Manage Care Special Pharm. 2017;23:S59–60.

Al-khafaji N, Aggarwal S, Loomba RS, Aggarwal G, Alla V. Trends in usage and outcomes associated with ultrafiltration in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134:A16047.

Anand V, Garg SK, Koene R, Thenappan T. National trends in hospital readmission rates in congestive heart failure patients. Circulation. 2016;134:A17286.

Anand V, Roy S, Koene R, Thenappan T. Trends in the hospitalizations for acute on chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the United States from 2003 to 2013. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1464.

Djawid Hashemi D, Dettmann L, Trippel TD, Bobenko A, Gelbrich G, Lindhorst R, et al. Economic impact of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from the prospective, randomized placebo-controlled ALDO-DHF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:155. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.833.

Givertz MM, Fonseca E, Yang M, Phess G, Rhodes T, Manzi MA, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs among us patients with worsening chronic heart failure: analysis of pinnacle registry linked with claims data. Circulation. 2017;136:A15468.

Krittanawong C, Yue B, Rivera MRR, Klomjit S, Wei X, Khandaker M, et al. Predicting hospital cost in patients with HFPEF: a contemporary analysis of national population-based cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(18)31317-2.

Lemor A, Lee S, Gholitabar F, Gongora CA, Castaneda D, Dominguez AC, et al. Impact of month of the year and weekend admissions on inpatient mortality and cost burden for congestive heart failure in 2013. Circulation. 2016;134:A15775.

Lemor A, Lee S, Gholitabar F, Gongora CA, Dominguez AC, Kroner PT, et al. Elective admissions for congestive heart failure are associated with higher inpatient mortality and hospital costs, a nationwide analysis using the national inpatient database of 2013. Circulation. 2016;134:A15637.

Mallikethi-Reddy S, Siddiqui F, Briasoulis A, Trehan N, Ashraf S, Kottam A, et al. Hospitalization burden of diastolic heart failure in the United States: 2007–2012. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(17)34281-X.

Masoomi R, Dawn B, Gupta K. Contemporary trends in pulmonary artery catheterization use in congestive heart failure: results from the United States national inpatient sample database. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:119. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw431.

Rich J, Miller L, Bostic R, O’Connell J, Mehra M. The epidemiology and economic burden of advanced stage heart failure in U.S. medicare beneficiaries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1368.

Yue B, Krittanawong C, Fang S, Wei X, Khandaker M, Weiss A, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is associated with lower inhospital mortality compared to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a nationwide analysis. Circulation. 2017;136:A19112.

Yue B, Krittanawong C, Wei X, Dominguez AC, Fang S, Khandaker M, et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea in patients hospitalized for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a nationwide analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(18)31425-6.

Albert NM, Swindle JP, Buysman EK, Chang C. Lower hospitalization and healthcare costs with sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker in a retrospective analysis of patients with heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(9):e011089. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011089.

Bress AP, King JB, Brixner D, Kielhorn A, Patel HK, Maya J, et al. Pharmacotherapy treatment patterns, outcomes, and health resource utilization among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction at a U.S. academic medical center. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(2):174–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1701.

Costanzo MR, Fonarow GC, Rizzo JA. Ultrafiltration versus diuretics for the treatment of fluid overload in patients with heart failure: a hospital cost analysis. J Med Econ. 2019;22(6):577–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2019.1584109.

Mark DB, Cowper PA, Anstrom KJ, Sheng S, Daniels MR, Knight JD, et al. Economic and quality-of-life outcomes of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(21):2551–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2184.

Park JD, Kim E, Werner RM. Inpatient hospital charge variability of U.S. hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1627–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3352-0.

Nguyen C, Zhang X, Evers T, Willey VJ, Tan H, Power TP. PCV55 treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilisation, and costs of care among patients with newly diagnosed systolic and diastolic heart failure in a US real-world setting. Value Health. 2019;22:S129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.491.

Shamliyan T, Nambiar S, Martin A. PCV63: what’s the cost of hospitalisations due to heart failure with preserved ejection fration in the United States? Value Health. 2019;22:S552–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.09.788.

Corbisiero R, Buck DC, Muller D, Bharmi R, Dalal N, Kazemian P. What is the cost of non-response to cardiac resynchronization therapy? Hospitalizations and healthcare utilization in the CRT-D population. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2016;47(2):189–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-016-0180-z.

Ramanathan R, Krishnan AM, Tandon V, Stringer B, Balakumaran K. Healthcare disparities in dementia patients admitted with CHF exacerbation: NIS database analyisis. Chest. 2019;156(4):A289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.340.

Amin A, Neuman WR, Lingohr-Smith M, Menges B, Lin J. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and risk in the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care among hospitalized acutely ill patients in the US: a retrospective analysis. Adv Ther. 2019;36(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0846-2.

Carey K, Stefos T. The cost of hospital readmissions: evidence from the VA. Health Care Manage Sci. 2016;19(3):241–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-014-9316-9.

Hernández-Madrid A, Lu X, Tsintzos SI, Fagan DH, Klepfer RN, Matía R, et al. Heart failure hospitalization reduction and cost savings achieved by improved delivery of effective biventricular pacing: economic implications of the OLE study under the US setting. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;11:385–93. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S205501.

Chung ES, St. John Sutton MG, Mealing S, Sidhu MK, Padhiar A, Tsintzos SI, et al. Economic value and cost-effectiveness of biventricular versus right ventricular pacing: results from the BLOCK-HF study. J Med Econ. 2019;22(10):1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2019.1652184.

Corbisiero R, Kazemian P, Buck D Jr, Bharmi R, Shah R, Muller DR. Healthcare savings associated with improvement of CRT response rate in the United States: medicare perspective. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(5):S190.

Fitch K, Lau J, Engel T, Medicis JJ, Mohr JF, Weintraub WS. The cost impact to medicare of shifting treatment of worsening heart failure from inpatient to outpatient management settings. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:855–63. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S184048.

Jackson SL, Tong X, King RJ, Loustalot F, Hong Y, Ritchey MD. National burden of heart failure events in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(12):e004873. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004873.

Joo H, Fang J, Losby JL, Wang G. Cost of informal caregiving for patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2015;169(1):142–148.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2014.10.010.

Adejumo AC, Adejumo KL, Adegbala OM, Chinedozi I, Ndansi J, Akanbi O, et al. Protein-energy malnutrition and outcomes of hospitalizations for heart failure in the USA. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(6):929–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.12.014.

Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Adegbala O, Sheikh MA, Singh M, Ahmed A, et al. Seasonal variation in in-patient mortality, cost of hospitalization and length of stay in heart failure patients in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):759. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(17)34148-7.

Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, Adegbala O, Sheikh M, Singh M, et al. Regional variation in mortality, length of stay, cost, and discharge disposition among patients admitted for heart failure in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(5):817–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.058.

Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, Orhurhu V, Ibrahim W, Kumar K, et al. Effect of hospital ownership on outcomes of heart failure hospitalization. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(5):831–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.06.009.

Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Bishu KG, Fonarow GC, Egede LE. Trends in health care expenditure among US adults with heart failure: the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2002–2011. Am Heart J. 2017;186:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2017.01.003.

Husaini BA, Levine RS, Norris KC, Cain V, Bazargan M, Moonis M. Heart failure hospitalization by race/ethnicity, gender and age in California: implications for prevention. Ethn Disease. 2016;26(3):345–54. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.26.3.345.

Inampudi C, Akintoye E, Bengaluru Jayanna M, Asleh R, Briasouli A, Alvarez P, et al. Trends in in-hospital mortality, length of stay, nonroutine discharge, and cost among end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis hospitalized with heart failure (2001–2014). J Cardiac Fail. 2019;25(7):524–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.02.020.

Lahewala S, Arora S, Tripathi B, Panaich S, Kumar V, Patel N, et al. Heart failure: same-hospital vs. different-hospital readmission outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 2019;278:186–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.12.043.

Polson M, Lord TC, Kangethe A, Speicher L, Farnum C, Brenner M, et al. Clinical and economic impact of hyperkalemia in patients with chronic kidney disease and heart failure. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:S2–9.

Tuzovic M, Yang EH, Sevag Packard RR, Ganz PA, Fonarow GC, Ziaeian B. National outcomes in hospitalized patients with cancer and comorbid heart failure. J Cardiac Fail. 2019;25(7):516–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.02.007.

Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Wang Y, Shen C, Yeh RW. 30-day episode payments and heart failure outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(5):379–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.11.010.

Ward A, Alvarez P, Vo L, Martin S. Direct medical costs of complications of diabetes in the United States: estimates for event-year and annual state costs (USD 2012). J Med Econ. 2014;17(3):176–83. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2014.882843.

Ziaeian B, Sharma PP, Yu T-C, Johnson KW, Fonarow GC. Factors associated with variations in hospital expenditures for acute heart failure in the United States. Am Heart J. 2015;169(2):282–9.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2014.11.007.

Woolley JM, Betts K, Mu F, Xiang C, Tang W, Wu E. Cost of hyperkalemia among patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134:A20014.

Amin AN, Ortendahl JD, Harmon AL, Kamat SA, Stellhorn RA, Chase SL, et al. Costs associated with unplanned readmissions among patients with heart failure with and without hyponatremia. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(6):374–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxy064.

Henk HJ, Paoli CJ, Gandra SR. A retrospective study to examine healthcare costs related to cardiovascular events in individuals with hyperlipidemia. Adv Ther. 2015;32(11):1104–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0264-7.

Yoon J, Fonarow GC, Groeneveld PW, Teerlink JR, Whooley MA, Sahay A, et al. Patient and facility variation in costs of VA heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(7):551–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2016.01.003.

Olchanski N, Vest AR, Cohen JT, DeNofrio D. Comparing inpatient costs of heart failure admissions for patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction with or without type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020;9(1):17–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCE.0000000000000190.

Corbisiero R, Kazemian P, Bharmi R, Shah R, Muller D. Less with more: hospitalization cost and event rates with quadripolar versus bipolar CRT-D System. Placing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39(10):1038–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.12923.

Kwok CS, Seferovic PM, Van Spall HGC, Helliwell T, Clarson L, Lawson C, et al. Early unplanned readmissions after admission to hospital with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(5):736–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.05.053.

Kwok CS, Zieroth S, Van Spall HGC, Helliwell T, Clarson L, Mohamed M, et al. The Hospital Frailty Risk Score and its association with in-hospital mortality, cost, length of stay and discharge location in patients with heart failure short running title: frailty and outcomes in heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2020;300:184–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.09.064.

Lee CS, Chien CV, Bidwell JT, Gelow JM, Denfeld QE, Creber RM, et al. Comorbidity profiles and inpatient outcomes during hospitalization for heart failure: an analysis of the U.S. Nationwide inpatient sample. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-73.

Doshi R, Majmundar M, Kansara T, Desai R, Shah J, Kumar A, et al. Frequency of cardiovascular events and in-hospital mortality with opioid overdose hospitalizations. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(10):1528–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.07.068.

Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Wang K, Lin Z, Bernheim SM, Xu X, et al. Association of hospital payment profiles with variation in 30-day Medicare cost for inpatients with heart failure or pneumonia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15604.

Valley TS, Sjoding MW, Ryan AM, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Intensive care unit admission and survival among older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, or myocardial infarction. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):943–51. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-847OC.

Kilgore M, Patel H, Kielhorn A, Maya J, Sharma P. Economic burden of hospitalizations of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2017;10:63–70. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.S130341.

Eubanks G, Haywood H, Sanders M, Byku M, Weickert T. Outpatient diuresis clinic: a patient centered and cost saving approach to heart failure management. J Cardiac Fail. 2019;25(8):S137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.07.395.

Obi EN, Swindle JP, Turner SJ, Russo PA, Altan A. Healthcare costs among patients with heart failure: a comparison of costs between matched decedent and survivor cohorts. Adv Ther. 2017;34(1):261–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0454-y.

Punekar RS, Fox KM, Richhariya A, Fisher MD, Cziraky M, Gandra SR, et al. Burden of first and recurrent cardiovascular events among patients with hyperlipidemia. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(8):483–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22428.

Park C, Fang J, Hawkins NA, Wang G. Comorbidity status and annual total medical expenditures in US hypertensive adults. Am J Prevent Med. 2017;53(6S2):S172–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.014.

Adamson PB, Roberts GJ, Gu NY, Bharmi R, Desai AS, Abraham WT. Economic impact of hemodynamic monitoring in heart failure patients: estimating the number-needed-to-treat and the break-even-point using a claims database. J Cardiac Fail. 2016;22:S87.

Drummond MFSM, Torrance GW, O’Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, Adegbala O, Alliu S, Sheikh M, et al. Seasonal variation in hospitalization outcomes in patients admitted for heart failure in the United States. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(11):1105–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22784.

Afzal A, Nisar T, Jamil AK, Kluger AY, Felius J, Hall SA, et al. Use of intra-aortic balloon pump in heart failure admissions requiring inotropic support in the United States between 2004–2014. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2019;38(4):S377–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2019.01.960.

Jatwani K, Jatwani S, Chugh K. Impact of hospital teaching status on hospital costs and length of stay for heart failure patients with history of hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a national inpatient sample analysis 2010–2014. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019;25(3):S377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.613.

Pandya S, Cao Y, Wang L, Baser O. Assessing the economic burden and 30-day readmission rates among patients with heart failure in the US veteran health administration population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:135–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4275.

Patel N, Kalra R, Doshi R, Joly J, Bajaj NS, Arora G, et al. Costs and in-hospital mortality associated with orthotopic heart transplants and left ventricular assist devices: national inpatient sample 2009–2014. Circulation. 2017;136:A20815.

Raju AD, Coutinho AD, Wang W, Shetty S, Sander SS, Coleman CI. Incremental burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients hospitalized for heart failure. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:20–1.

Swindle JP, Obi EN, Turner SJ, Blauer-Peterson CJ, Wacha LA, Altan A. Relationship between heart failure therapy and cost burden of heart failure in a managed care population. Heart Lung. 2016;45(4):374.

Swindle JP, Obi EN, Turner SJ, Russo PA, Chang C-L, Blauer-Peterson CJ, et al. Healthcare costs among patients with heart failure: comparisons between decedents and survivors over one year. J Cardiac Fail. 2016;22:S90.

Tashtish N, Al-Kindi SG, Oliveira GHM, Robinson MR. Length of stay and hospital charges for heart failure admissions in the United States: analysis of the national inpatient sample. J Cardiac Fail. 2017;23(8):S59.

Varma N, Bahu MM, Boehmer JP, Costanzo MR, Gold MR, Hirsh JB, et al. The cost of non-response to CRT: analysis from the Advance-CRT Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15(5):S370.

Alsalem ABZZ, Huang Y, Norton K, Wirth D, Lal AA, et al. Palliative care consultations for advanced heart failure patients: experience from a safety-net hospital. J Cardiac Fail. 2018;24(8):S94.

Desai AS, Bhimaraj A, Bharmi R, Jermyn R, Bhatt K, Shavelle D, et al. Ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring reduces heart failure hospitalizations in “real-world” clinical practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(19):2357–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.009.

Doshi R, Dhawan T, Rendon C, Rodriguez MA, Al-Khafaji JF, Taha M, et al. Incidence and implications of acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Internal and emergency medicine. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(3):421–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-019-02188-z.

Annavarapu S, Ghosh S, Li Y, Moretz C, Shetty S, Prewitt T. Healthcare resource utilization and costs among patients with cardiovascular, heart failure, or renal-related hospitalizations and type 2 diabetes. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:S40.

Krishnan AM, Tandon V, Ramanathan R, Mukarram O, Tabtabai S, Balakumaran K. Racial disparities in women admitted with peripartum cardiomyopathy: NIS database analysis. Chest. 2019;156(4):A1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1032.

Stafkey-Mailey D, Fuldeore R, Shetty S, Coutinho A, Landsman-Blumberg P, Sander S, et al. The cost of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus hospitalized for heart failure. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:S39–40.

Tandon V, Gabriel A, Balakumaran K, Tandon A, Conner C. Healthcare disparities in heart failure between African-Americans and Caucasian populations in the United States: a national review. Chest. 2019;156(4):A427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.457.

Tandon V, Tandon A, Gabriel A, Balakumaran K. Healthcare disparities in heart failure between Caucasian and Asian populations in the United States. Chest. 2019;156(4):A434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.464.

Sangaralingham LR, Sangaralingham SJ, Van Houten HK, Shah ND, Adigun RO, Dunlay SM. Real-world use of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure in the first year following FDA approval. Circulation. 2017;10:A019.

Vu MV, Carvalho N, Buchbinder R, McColl G, Clarke PM, Tran-Duy A. PSY13 impact of comorbid conditions on health care expenditure and work-related outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis using teh medical expenditure panel survey in the period 2006–2015. Value Health. 2019;22:S376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1838.

Munigala SBM, Goff ZD, Sagall R, Hauptman PJ. Evaluation of heart failure medication prescriptions using an online drug discount program. J Cardiac Fail. 2018;24(8):S78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.07.319.

Desai N, Reed P, Alvarez P, Oestreicher N, Owens M. Economic implications of hyperkalemia in a u.s. managed medicaid population. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:S14.

Fitch K, Pelizzari PM, Pyenson B. Inpatient utilization and costs for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(2):96–103.

Yue B, Krittanawong C, Wei X, Moradi A, Khandaker MK, Fang S, et al. Heart failure admission on weekends is associated with shorter length of stay and lower healthcare costs compared to weekdays: a nationwide sample during 2014. Circulation. 2017;136:A18745.

Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Adegbala O, Sheikh MA, Singh M, Ahmed A, et al. Regional variation in hospitalization outcomes among patients admitted for heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(17)34160-8.

Garrison LP Jr, Pauly MV, Willke RJ, Neumann PJ. An overview of value, perspective, and decision context: a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force report. Value Health. 2018;21(2):124–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.006.

Amin A, Bucior I, Lingohr-Smith M, Menges B, Lin J, Deitelzweig S. Burden of hospital readmissions for venous thromboembolism among patients hospitalized for non-cancer acute medical illness in the US. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3:765–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12229.

Arora S, Patel P, Lahewala S, Patel N, Patel NJ, Thakore K, et al. Etiologies, trends, and predictors of 30-day readmission in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119(5):760–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.022.

McAlister FA, Youngson E, Kaul P. Patients with heart failure readmitted to the original hospital have better outcomes than those readmitted elsewhere. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5):e004892. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004892.

Kim H, Hung WW, Paik MC, Ross JS, Zhao Z, Kim GS, et al. Predictors and outcomes of unplanned readmission to a different hospital. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(6):513–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv082.

Vidic A, Chibnall JT, Hauptman PJ. Heart failure is a major contributor to hospital readmission penalties. J Card Fail. 2015;21(2):134–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.002.

Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Shi Q, Morlan B, VanHouten H, Hall Long K, et al. Lifetime costs of medical care after heart failure diagnosis. Circulation. 2011;4(1):68–75. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.110.957225.

Stewart SJA, Buchan S, McGuire A, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. The current cost of heart failure to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(3):361–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00198-2.