Abstract

Background

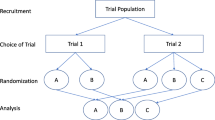

A significant limitation of the traditional randomized controlled trials is that strong preferences for (or against) one treatment may influence outcomes and/or willingness to receive treatment. Several trial designs incorporating patient preference have been introduced to examine the effect of treatment preference separately from the effects of individual interventions. In the current study, we summarized results from studies using doubly randomized preference trial (DRPT) or fully randomized preference trial (FRPT) designs and examined the effect of treatment preference on clinical outcomes.

Methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Studies using DRPT or FRPT design were identified using electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Google Scholar between January 1989 and November 2018. All studies included in this meta-analysis were examined to determine the extent to which giving patients their preferred treatment option influenced clinical outcomes. The following data were extracted from included studies: study characteristics, sample size, study duration, follow-up, patient characteristics, and clinical outcomes. We further appraised risk of bias for the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool.

Results

The search identified 374 potentially relevant articles, of which 27 clinical trials utilized a DRPT or FRPT design and were included in the final analysis. Overall, patients who were allocated to their preferred treatment intervention were more likely to achieve better clinical outcomes [effect size (ES) = 0.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10–0.26]. Subgroup analysis also found that mental health as well as pain and functional disorders moderated the preference effect (ES = 0.23, 95% CI 0.11–0.36, and ES = 0.09, 95% CI 0.03–0.15, respectively).

Conclusions

Matching patients to preferred interventions has previously been shown to promote outcomes such as satisfaction and treatment adherence. Our analysis of current evidence showed that allowing patients to choose their preferred treatment resulted in better clinical outcomes in mental health and pain than giving them a treatment that is not preferred. These results underline the importance of incorporating patient preference when making treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6.

Sidani S, Epstein DR, Bootzin RR, Moritz P, Miranda J. Assessment of preferences for treatment: validation of a measure. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(4):419–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20329.

George SZ, Robinson ME. Preference, expectation, and satisfaction in a clinical trial of behavioral interventions for acute and sub-acute low back pain. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1074–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.016.

Kwan BM, Dimidjian S, Rizvi SL. Treatment preference, engagement, and clinical improvement in pharmacotherapy versus psychotherapy for depression. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(8):799–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.04.003.

Leykin Y, Derubeis RJ, Gallop R, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Hollon SD. The relation of patients’ treatment preferences to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):209–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.002.

Le QA, Doctor JN, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Effects of treatment, choice, and preference on health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Qual Life Res. 2018;27(6):1555–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1833-4.

Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, Manber R, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(3):354–61.

Torgerson D, Sibbald B. Understanding controlled trials: what is a patient preference trial? BMJ. 1998;316(7128):360.

King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Bower P, Chandler M, Morou M, et al. Impact of participant and physician intervention preferences on randomized trials: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293(9):1089–99. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.9.1089.

Walter SD, Turner R, Macaskill P, McCaffery KJ, Irwig L. Beyond the treatment effect: evaluating the effects of patient preferences in randomised trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2014;26(1):489–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280214550516.

Rucker G. A two-stage trial design for testing treatment, self-selection and treatment preference effects. Stat Med. 1989;8(4):477–85.

Torgerson DJ, Klaber-Moffett J, Russell IT. Patient preferences in randomised trials: threat or opportunity? J Health Services Res Policy. 1996;1(4):194–7.

Brewin CR, Bradley C. Patient preferences and randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1989;299(6694):313–5.

Swift JK, Callahan JL. The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(4):368–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20553.

Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):155–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20759.

Lindhiem O, Bennett CB, Trentacosta CJ, McLear C. Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(6):506–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.002.

Preference Collaborative Review Group. Patients’ preferences within randomised trials: systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. Br Med J. 2008;337:1864. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1864.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Public Libr Sci Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Marcus SM, Stuart EA, Wang P, Shadish WR, Steiner PM. Estimating the causal effect of randomization versus treatment preference in a doubly randomized preference trial. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(2):244–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028031.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator [Online calculator]. https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/research-resources/research-for-resources/effect-size-calculator.html. Accessed 10 Jan 2019.

Borenstein M. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03.

McCaffery KJ, Turner R, Macaskill P, Walter SD, Chan SF, Irwig L. Determining the impact of informed choice: separating treatment effects from the effects of choice and selection in randomized trials. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(2):229–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x10379919.

Burke LE, Warziski M, Styn MA, Music E, Hudson AG, Sereika SM. A randomized clinical trial of a standard versus vegetarian diet for weight loss: the impact of treatment preference. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):166–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803706.

Renjilian DA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Anton SD. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(4):717–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.717.

Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, Liu CF, Heagerty P, Felker BL, et al. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):164–73. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3002_9.

Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Ichikawa L, Avins AL, Delaney K, Barlow WE, et al. Treatment expectations and preferences as predictors of outcome of acupuncture for chronic back pain. Spine. 2010;35(15):1471–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c2a8d3.

Mergl R, Henkel V, Allgaier AK, Kramer D, Hautzinger M, Kohnen R, et al. Are treatment preferences relevant in response to serotonergic antidepressants and cognitive-behavioral therapy in depressed primary care patients? Results from a randomized controlled trial including a patients’ choice arm. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1159/000318772.

Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, Kriston L, Niebling W, Harter M. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):324–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023.

Delsignore A, Schnyder U. Control expectancies as predictors of psychotherapy outcome: a systematic review. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46(Pt 4):467–83. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466507x226953.

Bradley C. Designing medical and educational intervention studies. A review of some alternatives to conventional randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(2):509–18.

Cook T, Campbell D. Quasi-experimentation: design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1979.

Bower P, King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Sibbald B. Patient preferences in randomised controlled trials: conceptual framework and implications for research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):685–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.010.

Janevic MR, Janz NK, Dodge JA, Lin X, Pan W, Sinco BR, et al. The role of choice in health education intervention trials: a review and case study. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2003;56(7):1581–94.

Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte-Rivera V, Mletzko-Crowe T, Kinkead B, Ritchie JC, et al. Effects of patient preferences on outcomes in the predictors of remission in depression to individual and combined treatments (PReDICT) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(6):546–56. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050517.

Stewart MJ, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Nicholas MK. Patient and clinician treatment preferences do not moderate the effect of exercise treatment in chronic whiplash-associated disorders. Eur J Pain. 2008;12(7):879–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.12.009.

Yancy WS Jr, Mayer SB, Coffman CJ, Smith VA, Kolotkin RL, Geiselman PJ, et al. Effect of allowing choice of diet on weight loss: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(12):805–14. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-2358.

Shay LE, Seibert D, Watts D, Sbrocco T, Pagliara C. Adherence and weight loss outcomes associated with food-exercise diary preference in a military weight management program. Eat Behav. 2009;10(4):220–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.004.

Adamson SJ, Sellman DJ, Dore GM. Therapy preference and treatment outcome in clients with mild to moderate alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24(3):209–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230500167502.

Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.1.14.

Cockayne S, Hicks K, Kangombe AR, Hewitt C, Concannon M, Thomas K, et al. The effect of patients’ preference on outcome in the EVerT cryotherapy versus salicylic acid for the treatment of plantar warts (verruca) trial. J Foot Ankle Res. 2012;5(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1146-5-28.

Bowling A, Rowe G. “You decide doctor”. What do patient preference arms in clinical trials really mean? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2005;59(11):914–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.035261.

Corbett MS, Watson J, Eastwood A. Randomised trials comparing different healthcare settings: an exploratory review of the impact of pre-trial preferences on participation, and discussion of other methodological challenges. BioMed Central Health Services Res. 2016;16(1):589. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1823-6.

McKay JR, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Snider EC, O’Brien CP. Effects of random versus nonrandom assignment in a comparison of inpatient and day hospital rehabilitation for male alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(1):70–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.1.70.

Rokke PD, Tomhave JA, Jocic Z. The role of client choice and target selection in self-management therapy for depression in older adults. Am Psychol Assoc. 1999;14:155–69.

Noel PH, Larme AC, Meyer J, Marsh G, Correa A, Pugh JA. Patient choice in diabetes education curriculum. Nutritional versus standard content for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(6):896–901.

Long Q, Little RJ, Lin X. Causal inference in hybrid intervention trials involving treatment choice. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(482):474–84. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214507000000662.

Clark NM, Janz NK, Dodge JA, Mosca L, Lin X, Long Q, et al. The effect of patient choice of intervention on health outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(5):679–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.002.

Zoellner LA, Roy-Byrne PP, Mavissakalian M, Feeny NC. Doubly randomized preference trial of prolonged exposure versus sertraline for treatment of PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(4):287–96. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17090995.

Moffett JK, Torgerson D, Bell-Syer S, Jackson D, Llewlyn-Phillips H, Farrin A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of exercise for low back pain: clinical outcomes, costs, and preferences. BMJ. 1999;319(7205):279. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7205.279.

Thomas E, Croft PR, Paterson SM, Dziedzic K, Hay EM. What influences participants’ treatment preference and can it influence outcome? Results from a primary care-based randomised trial for shoulder pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(499):93–6.

Carr JL, Klaber Moffett JA, Howarth E, Richmond SJ, Torgerson DJ, Jackson DA, et al. A randomized trial comparing a group exercise programme for back pain patients with individual physiotherapy in a severely deprived area. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(16):929–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500030639.

Moffett JK, Jackson DA, Richmond S, Hahn S, Coulton S, Farrin A, et al. Randomised trial of a brief physiotherapy intervention compared with usual physiotherapy for neck pain patients: outcomes and patients’ preference. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):75. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38286.493206.82.

Moffett JK, Jackson DA, Gardiner ED, Torgerson DJ, Coulton S, Eaton S, et al. Randomized trial of two physiotherapy interventions for primary care neck and back pain patients: ‘McKenzie’ vs brief physiotherapy pain management. Rheumatology. 2006;45(12):1514–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel339.

Salter GC, Roman M, Bland MJ, MacPherson H. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain: a pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BioMed Central Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-7-99.

Johnson RE, Jones GT, Wiles NJ, Chaddock C, Potter RG, Roberts C, et al. Active exercise, education, and cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent disabling low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32(15):1578–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318074f890.

McLean SM, Klaber Moffett JA, Sharp DM, Gardiner E. A randomised controlled trial comparing graded exercise treatment and usual physiotherapy for patients with non-specific neck pain (the GET UP neck pain trial). Man Ther. 2013;18(3):199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.09.005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QAL conceived the research and contributed to the development of the study design. Both authors screened a portion of abstracts and performed full-text review. DD oversaw quality appraisal tasks and drafted the manuscript. Both authors provided critical review in the draft of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Unrestricted funding was received through the PhRMA Foundation Value Assessment Research Award.

Conflict of Interest

Dimittri Delevry and Quang A. Le have no conflicts of interests that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Electronic Supplementary Material files.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delevry, D., Le, Q.A. Effect of Treatment Preference in Randomized Controlled Trials: Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Patient 12, 593–609 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00379-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00379-6