Abstract

Purpose

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are increasingly used in clinical trials to provide patients’ perspectives regarding symptoms, health-related quality of life, and satisfaction with treatments. A range of guidance documents exist for the selection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in clinical trials, and it is unclear to what extent these documents present consistent recommendations.

Methods

We conducted a targeted review of publications and regulatory guidance documents that advise on the selection of PROMs for use in clinical trials. A total of seven guidance documents from the US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and scientific consortia from professional societies were included in the final review. Guidance documents were analyzed using a content analysis approach comparing them with minimum standards recommended by the International Society for Quality of Life Research.

Results

Overall there was substantial agreement between guidance regarding the appropriate considerations for PROM selection within a clinical trial. Variations among the guidance primarily related to differences in their format and differences in the perspectives and mandates of their respective organizations. Whereas scientific consortia tended to produce checklist or rating-type guidance, regulatory groups tended to use more narrative-based approaches sometimes supplemented with lists of criteria.

Conclusion

The consistency in recommendations suggests an emerging consensus in the field and supports use of any of the major guidance documents available to guide PROM selection for clinical trials without concern of conflicting recommendations. This work represents an important first step in the international PROTEUS Consortium’s ongoing efforts to optimize the use of PROs in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Acquadro, C., et al. (2003). Incorporating the patient's perspective into drug development and communication: An ad hoc task force report of the patient-reported outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value Health, 6(5), 522–531.

Au, H. J., et al. (2010). Added value of health-related quality of life measurement in cancer clinical trials: The experience of the NCIC CTG. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 10(2), 119–128.

Till, J. E., et al. (1994). Research on health-related quality of life: Dissemination into practical applications. Quality of Life Research, 3(4), 279–283.

Lipscomb, J., Gotay, C. C., & Snyder, C. (2004). Outcomes assessment in cancer: Measures, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brundage, M., et al. (2011). A knowledge translation challenge: Clinical use of quality of life data from cancer clinical trials. Quality of Life Research, 20(7), 979–985.

Bezjak, A., et al. (2001). Oncologists' use of quality of life information: Results of a survey of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group physicians. Quality of Life Research, 10(1), 1–13.

Basch, E., et al. (2015). Patient-reported outcomes in cancer drug development and us regulatory review: Perspectives from industry, the food and drug administration, and the patient. JAMA Oncology, 1(3), 375–379.

Basch, E., et al. (2017). Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA, 318(2), 197–198.

Kyte, D., et al. (2019). Systematic evaluation of patient-reported outcome protocol content and reporting in cancer trials. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 111, 1170.

Ahmed, K., et al. (2016). Systematic evaluation of patient-reported outcome (PRO) protocol content and reporting in UK cancer clinical trials: The EPiC study protocol. British Medical Journal Open, 6(9), e012863.

Mercieca-Bebber, R., et al. (2016). The patient-reported outcome content of international ovarian cancer randomised controlled trial protocols. Quality of Life Research, 25(10), 2457–2465.

The PROTEUS Consortium (2020). Retrieved from www.TheProteusConsortium.org. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

Reeve, B. B., et al. (2013). ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Quality of Life Research, 22(8), 1889–1905.

Calvert, M., et al. (2018). Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: The SPIRIT-PRO extension. JAMA, 319(5), 483–494.

Coens, C., et al. (2020). International standards for the analysis of quality-of-life and patient-reported outcome endpoints in cancer randomised controlled trials: Recommendations of the SISAQOL Consortium. The Lancet Oncology, 21(2), e83–e96.

Calvert, M., et al. (2013). Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: The CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA, 309(8), 814–822.

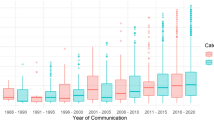

Snyder, C., et al. (2019). Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: Recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Quality of Life Research, 28(2), 345–356.

Wu, A. W., et al. (2014). Clinician's checklist for reading and using an article about patient-reported outcomes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(5), 653–661.

EMA. (2016). Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. The use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies. Amsterdam: EMA.

US Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration.

Lohr, K. N. (2002). Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research, 11(3), 93–205.

Eichenfield, L. F., et al. (2017). Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: A comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 139(4s), S49–S57.

Makady, A., et al. (2017). Policies for use of real-world data in health technology assessment (HTA): A comparative study of six HTA agencies. Value Health, 20(4), 520–532.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Patrick, D. L., et al. (2011). Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: Part 2–assessing respondent understanding. Value Health, 14(8), 978–988.

Patrick, D. L., et al. (2011). Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 1–eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health, 14(8), 967–977.

Rothman, M., et al. (2009). Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: The ISPOR good research practices for evaluating and documenting content validity for the use of existing instruments and their modification PRO task force report. Value Health, 12(8), 1075–1083.

COSMIN Initiative. (2020). Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://www.cosmin.nl/finding-right-tool/select-best-measurement-instrument/.

Prinsen, C. A., et al. (2018). COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1147–1157.

Terwee, C. B., et al. (2018). COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Quality of Life Research: AN International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 27(5), 1159–1170.

Mokkink, L. B., et al. (2018). COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1171–1179.

Prinsen, C. A. C., et al. (2016). How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”—A practical guideline. Trials, 17(1), 449.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Patient-focused drug development: Collecting comprehensive and representative input, in draft guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Valderas, J. M., et al. (2008). Development of EMPRO: A tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures. Value in Health, 11(4), 700–708.

Evaluating Measures of Patient-Reported Outcomes (EMPRO). (2019). Retrieved December 16, 2019, from https://medicine.exeter.ac.uk/research/healthresearch/healthservicesandpolicy/projects/proms/theemprotool/.

Luckett, T., & King, M. T. (2010). Choosing patient-reported outcome measures for cancer clinical research – Practical principles and an algorithm to assist non-specialist researchers. European Journal of Cancer, 46(18), 3149–3157.

Revicki, D., et al. (2008). Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 1102–1109.

Mokkink, L. B., et al. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 539–549.

Wild, D., Eremenco, S., Mear, I., et al. (2009). Multinational trials – recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: The ISPOR patient reported outcomes translation & linguistic validation good research practices task force report. Value in Health, 12, 430–440.

Wild, D., et al. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health, 8(2), 94–104.

Dewolf, L., et al. (2009). EORTC Quality of life group translation procedure (3rd ed.). Brussels: EORTC. https://abdn.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/eortc-quality-of-life-group-translation-procedure. Accessed 9 Sep 2020.

Basch, E., et al. (2012). Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(34), 4249–4255.

Kluetz, P. G., O'Connor, D. J., & Soltys, K. (2018). Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. The lancet Oncology, 19(5), e267–e274.

Mercieca-Bebber, R., et al. (2018). The importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and strategies for future optimization. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 9, 353–367.

COSMIN Study Design checklist for Patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf#. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

European Medicines Agency. (2005). Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency.

Aaronson, N. K., et al. (1991). Quality of life research in oncology. Past achievements and future priorities. Cancer, 67(S3), 839–843.

European Medicines Agency. (2018). Guideline on the development of new medicinal products for the treatment of Crohn’s Disease. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency.

European Medicines Agency. (2018). EMA regulatory science to 2025. Amsterdam: European Medicines Agency.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many guidance authors who responded to our requests for feedback.

Funding

Funded by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Eugene Washington Engagement Award (12565-JHU). Dr. Snyder is a member of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins (NCI P30 CA006973).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MC reports grants from Macmillan Cancer Support, Innovate UK, Health Data Research UK, UCB Pharma the NIHR, NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC) at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, and personal fees from Astellas, Takeda, Glaukos and Merck outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crossnohere, N.L., Brundage, M., Calvert, M.J. et al. International guidance on the selection of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical trials: a review. Qual Life Res 30, 21–40 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02625-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02625-z