Abstract

Background

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are used to elicit preferences of current and future patients and healthcare professionals about how they value different aspects of healthcare. Risk is an integral part of most healthcare decisions. Despite the use of risk attributes in DCEs consistently being highlighted as an area for further research, current methods of incorporating risk attributes in DCEs have not been reviewed explicitly.

Objectives

This study aimed to systematically identify published healthcare DCEs that incorporated a risk attribute, summarise and appraise methods used to present and analyse risk attributes, and recommend best practice regarding including, analysing and transparently reporting the methodology supporting risk attributes in future DCEs.

Data Sources

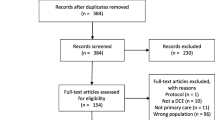

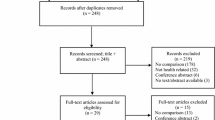

The Web of Science, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Econlit databases were searched on 18 April 2013 for DCEs that included a risk attribute published since 1995, and on 23 April 2013 to identify studies assessing risk communication in the general (non-DCE) health literature.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Healthcare-related DCEs with a risk attribute mentioned or suggested in the title/abstract were obtained and retained in the final review if a risk attribute meeting our definition was included.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods

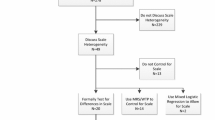

Extracted data were tabulated and critically appraised to summarise the quality of reporting, and the format, presentation and interpretation of the risk attribute were summarised.

Results

This review identified 117 healthcare DCEs that incorporated at least one risk attribute. Whilst there was some evidence of good practice incorporated into the presentation of risk attributes, little evidence was found that developing methods and recommendations from other disciplines about effective methods and validation of risk communication were systematically applied to DCEs. In general, the reviewed DCE studies did not thoroughly report the methodology supporting the explanation of risk in training materials, the impact of framing risk, or exploring the validity of risk communication.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this review was that the methods underlying presentation, format and analysis of risk attributes could only be appraised to the extent that they were reported.

Conclusions

Improvements in reporting and transparency of risk presentation from conception to the analysis of DCEs are needed. To define best practice, further research is needed to test how the process of communicating risk affects the way in which people value risk attributes in DCEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

Tversky A, Wakker P. Risk attitudes and decision weights. Econometrica. 1995;63(6):1255–80.

Hammitt JK, Graham JD. Willingness to pay for health protection: inadequate sensitivity to probability? J Risk Uncertainty. 1999;18(1):33–62.

Visschers VHM, Meertens RM, Passchier WWF, de Vries NNK. Probability information in risk communication: a review of the research literature. Risk Anal. 2009;29(2):267–87.

Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risk: suggested best practices and future recommendations. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):696–713.

Peters E, Hart PS, Fraenkel L. Informing patients: the influence of numeracy, framing, and format of side effect information on risk perceptions. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):432–6.

Corso PS, Hammitt JK, Graham JD. Valuing mortality-risk reduction: using visual aids to improve the validity of contingent valuation. J Risk Uncertainty. 2001;23(2):165–84.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Louviere JJ, Lancsar E. Choice experiments in health: the good, the bad, the ugly and toward a brighter future. Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4(4):527–46.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Johansson P. Evaluating health risks: an economic approach. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Cameron TA, DeShazo JR, Johnson EH. The effect of children on adult demands for health-risk reductions. J Health Econ. 2010;29(3):364–76.

Tsuge T, Kishimoto A, Takeuchi K. A choice experiment approach to the valuation of mortality. J Risk Uncertainty. 2005;31(1):73–95.

Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, Allore HG, Salmon JC, Foody JM, et al. Health outcome priorities among competing cardiovascular, fall injury, and medication-related symptom outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1409–16.

Pignone MP, Howard K, Brenner AT, Crutchfield TM, Hawley ST, Lewis CL, et al. Comparing 3 techniques for eliciting patient values for decision making about prostate-specific antigen screening: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(5):11.

Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, Foody JM, Bianco L, Ginter S, et al. Development of a tool for eliciting patient priority from among competing cardiovascular disease, medication-symptoms, and fall injury outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):730–6.

Oteng B, Marra F, Lynd LD, Ogilvie G, Patrick D, Marra CA. Evaluating societal preferences for human papillomavirus vaccine and cervical smear test screening programme. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(1):52–7.

Sweeting KR, Whitty JA, Scuffham PA, Yelland MJ. Patient preferences for treatment of achilles tendon pain: results from a discrete-choice experiment. Patient. 2011;4(1):45–54.

Pignone MP, Brenner AT, Hawley S, Sheridan SL, Lewis CL, Jonas DE, et al. Conjoint analysis versus rating and ranking for values elicitation and clarification in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27(1):45–50.

Laba TL, Brien JA, Jan S. Understanding rational non-adherence to medications: a discrete choice experiment in a community sample in Australia. BMC Family Practice. 2012;13:61.

Boeri M, Longo A, Grisolia JM, Hutchinson WG, Kee F. The role of regret minimisation in lifestyle choices affecting the risk of coronary heart disease. J Health Econ. 2013; 32(1):253–60.

Kauf TL, Mohamed AF, Hauber AB, Fetzer D, Ahmad A. Patients’ willingness to accept the risks and benefits of new treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Patient. 2012;5(4):265–78.

Guo N, Marra CA, FitzGerald JM, Elwood RK, Anis AH, Marra F. Patient preference for latent tuberculosis infection preventive treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2011;14(6):937–43.

Scalone L, Watson V, Ryan M, Kotsopoulos N, Patel R. Evaluation of patients’ preferences for genital herpes treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):802–7.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Rose JM, Donkers B, Essink-Bot M-L, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW. Men’s preferences for prostate cancer screening: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):19.

Vlemmix F, Kuitert M, Bais J, Opmeer B, van der Post J, Mol BW, et al. Patient’s willingness to opt for external cephalic version. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2013;34(1):15–21.

Damen TH, de Bekker-Grob EW, Mureau MA, Menke-Pluijmers MB, Seynaeve C, Hofer SO, et al. Patients’ preferences for breast reconstruction: a discrete choice experiment. J Plastic Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(1):75–83.

Regier DA, Diorio C, Ethier MC, Alli A, Alexander S, Boydell KM, et al. Discrete choice experiment to evaluate factors that influence preferences for antibiotic prophylaxis in pediatric oncology. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47470.

Marti J. Assessing preferences for improved smoking cessation medications: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(5):533–48.

Tinelli M, Ozolins M, Bath-Hextall F, Williams HC. What determines patient preferences for treating low risk basal cell carcinoma when comparing surgery vs imiquimod? A discrete choice experiment survey from the SINS trial. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:19.

Johnson FR, Manjunath R, Mansfield CA, Clayton LJ, Hoerger TJ, Zhang P. High-risk individuals’ willingness to pay for diabetes risk-reduction programs. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1351–6.

Doyle S, Lloyd A, Birt J, Curtis B, Ali S, Godbey K, et al. Willingness to pay for obesity pharmacotherapy. Obesity. 2012;20(10):2019–26.

Fiebig DG, Knox S, Viney R, Haas M, Street DJ. Preferences for new and existing contraceptive products. Health Econ. 2011;20 Suppl 1:35–52.

Walzer S. What do parents want from their child’s asthma treatment? Ther Clin Risk Manage. 2007;3(1):167–75.

Chancellor J, Martin M, Liedgens H, Baker MG, Muller-Schwefe GH. Stated preferences of physicians and chronic pain sufferers in the use of classic strong opioids. Value Health. 2012;15(1):106–17.

Lloyd A, McIntosh E, Rabe KF, Williams A. Patient preferences for asthma therapy: a discrete choice experiment. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(4):241–8.

Ossa DF, Briggs A, McIntosh E, Cowell W, Littlewood T, Sculpher M. Recombinant erythropoietin for chemotherapy-related anaemia: economic value and health-related quality-of-life assessment using direct utility elicitation and discrete choice experiment methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(3):223–37.

Lloyd A, McIntosh E, Price M. The importance of drug adverse effects compared with seizure control for people with epilepsy: a discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(11):1167–81.

Shafey M, Lupichuk SM, Do T, Owen C, Stewart DA. Preferences of patients and physicians concerning treatment options for relapsed follicular lymphoma: a discrete choice experiment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(7):962–9.

Essers BA, van Helvoort-Postulart D, Prins MH, Neumann M, Dirksen CD. Does the inclusion of a cost attribute result in different preferences for the surgical treatment of primary basal cell carcinoma? A comparison of two discrete-choice experiments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(6):507–20.

Salkeld G, Solomon M, Short L, Ryan M, Ward JE. Evidence-based consumer choice: a case study in colorectal cancer screening. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27(4):449–55.

McTaggart-Cowan HM, Shi P, Fitzgerald JM, Anis AH, Kopec JA, Bai TR, et al. An evaluation of patients’ willingness to trade symptom-free days for asthma-related treatment risks: a discrete choice experiment. J Asthma. 2008;45(8):630–8.

Howard K, Salkeld G. Does attribute framing in discrete choice experiments influence willingness to pay? Results from a discrete choice experiment in screening for colorectal cancer. Value Health. 2009;12(2):354–63.

Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Ali S, Hashmi N, Newal D, Najib H. Preferences for antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2011;108(6):868–73.

Lloyd A, Penson D, Dewilde S, Kleinman L. Eliciting patient preferences for hormonal therapy options in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11(2):153–9.

Hall J, Kenny P, King M, Louviere J, Viney R, Yeoh A. Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to evaluate the introduction of varicella vaccination. Health Econ. 2002;11(5):457–65.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Hofman R, Donkers B, van Ballegooijen M, Helmerhorst TJM, Raat H, et al. Girls’ preferences for HPV vaccination: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine. 2010;28(41):6692–7.

Ratcliffe J, Buxton M, McGarry T, Sheldon R, Chancellor J. Patients’ preferences for characteristics associated with treatments for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43(3):337–45.

Pereira CC, Mulligan M, Bridges JF, Bishai D. Determinants of influenza vaccine purchasing decision in the US: a conjoint analysis. Vaccine. 2011;29(7):1443–7.

Lee WC, Joshi AV, Woolford S, Sumner M, Brown M, Hadker N, et al. Physicians’ preferences towards coagulation factor concentrates in the treatment of Haemophilia with inhibitors: a discrete choice experiment. Haemophilia. 2008;14(3):454–65.

Scalone L, Mantovani LG, Borghetti F, Von MS, Gringeri A. Patients’, physicians’, and pharmacists’ preferences towards coagulation factor concentrates to treat haemophilia with inhibitors: results from the COHIBA Study. Haemophilia. 2009;15(2):473–86.

Mantovani LG, Monzini MS, Mannucci PM, Scalone L, Villa M, Gringeri A, et al. Differences between patients’, physicians’ and pharmacists’ preferences for treatment products in haemophilia: a discrete choice experiment. Haemophilia. 2005;11(6):589–97.

Espelid I, Cairns J, Askildsen JE, Qvist V, Gaarden T, Tveit AB. Preferences over dental restorative materials among young patients and dental professionals. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114(1):15–21.

Lee A, Gin T, Lau AS, Ng FF. A comparison of patients’ and health care professionals’ preferences for symptoms during immediate postoperative recovery and the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(1):87–93.

Eberth B, Watson V, Ryan M, Hughes J, Barnett G. Does one size fit all? Investigating heterogeneity in men’s preferences for benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment using mixed logit analysis. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(6):707–15.

van Dam L, Hol L, de Bekker-Grob EW, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Habbema JD, et al. What determines individuals’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening programmes? A discrete choice experiment. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(1):150–9.

Torbica A, Fattore G. Understanding the impact of economic evidence on clinical decision making: a discrete choice experiment in cardiology. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(10):1536–43.

Nayaradou M, Berchi C, Dejardin O, Launoy G. Eliciting population preferences for mass colorectal cancer screening organization. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):224–33.

Griffith JM, Lewis CL, Hawley S, Sheridan SL, Pignone MP. Randomized trial of presenting absolute v. relative risk reduction in the elicitation of patient values for heart disease prevention with conjoint analysis. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(2):167–74.

Weston A, Fitzgerald P. Discrete choice experiment to derive willingness to pay for methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy versus simple excision surgery in basal cell carcinoma. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(18):1195–208.

Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Falvey H. Treatment preferences and medication adherence of people with type 2 diabetes using oral glucose-lowering agents. Diabet Med. 2009;26(4):416–24.

Schaarschmidt ML, Schmieder A, Umar N, Terris D, Goebeler M, Goerdt S, et al. Patient preferences for psoriasis treatments: process characteristics can outweigh outcome attributes. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(11):1285–94.

Schmieder A, Schaarschmidt ML, Umar N, Terris DD, Goebeler M, Goerdt S, et al. Comorbidities significantly impact patients’ preferences for psoriasis treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(3):363–72.

Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Watson ME, Johnson FR, Hernandez JE. Benefits, risk, and uncertainty: preferences of antiretroviral-naive African Americans for HIV treatments. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(1):29–34.

Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–8.

Salisbury LC, Feinberg FM. Alleviating the constant stochastic variance assumption in decision research: theory, measurement, and experimental test. Mark Sci. 2010;29(1):1–17.

Fiebig DG, Keane MP, Louviere J, Wasi N. The generalized multinomial logit model: accounting for scale and coefficient heterogeneity. Mark Sci. 2010;29(3):393–421.

Muhlbacher AC, Lincke HJ, Nubling M. Evaluating patients’ preferences for multiple myeloma therapy, a Discrete-Choice-Experiment. Psychosoc Med. 2008; 5:Doc10.

Shackley P, Slack R, Michaels J. Vascular patients’ preferences for local treatment: an application of conjoint analysis. J Health Services Res Policy. 2001;6(3):151–7.

Bridges JF, Searle SC, Selck FW, Martinson NA. Designing family-centered male circumcision services: a conjoint analysis approach. Patient. 2012;5(2):101–11.

Goto R, Takahashi Y, Ida T. Changes in smokers’ attitudes toward intended cessation attempts in Japan. Value Health. 2011;14(5):785–91.

Ashcroft DM, Seston E, Griffiths CE. Trade-offs between the benefits and risks of drug treatment for psoriasis: a discrete choice experiment with U.K. dermatologists. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(6):1236–41.

Yeung RYT, Smith RD, Mcghee SM. Willingness to pay and size of health benefit: an integrated model to test for ‘sensitivity to scale’. Health Econ. 2003;12(9):791–6.

Heberlein TA, Wilson MA, Bishop RC, Schaeffer NC. Rethinking the scope test as a criterion for validity in contingent valuation. J Environ Econ Manage. 2005;50(1):1–22.

Carson RT, Flores NE, Meade NF. Contingent valuation: controversies and evidence. Environ Resour Econ. 2001;19(2):173–210.

Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Mansfield C, Hass S, Miller DW, Siegel CA, et al. Crohn’s disease patients’ risk–benefit preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):769–79.

Johnson FR, Van Houtven G, Ozdemir S, Hass S, White J, Francis G, et al. Multiple sclerosis patients’ benefit–risk preferences: serious adverse event risks versus treatment efficacy. J Neurol. 2009;256(4):554–62.

Johnson FR, Hauber AB, Ozdemir S, Lynd L. Quantifying women’s stated benefit-risk trade-off preferences for IBS treatment outcomes. Value Health. 2010;13(4):418–23.

Telser H, Zweifel P. Measuring willingness-to-pay for risk reduction: an application of conjoint analysis. Health Econ. 2002;11(2):129–39.

Telser H, Zweifel P. Validity of discrete-choice experiments evidence for health risk reduction. Appl Econ. 2007;39(1):68–78.

Berry D, Raynor T, Knapp P, Bersellini E. Over the counter medicines and the need for immediate action: a further evaluation of European Commission recommended wordings for communicating risk. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):129–34.

Cuite CL, Weinstein ND, Emmons K, Colditz G. A test of numeric formats for communicating risk probabilities. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(3):377–84.

France J, Keen C, Bowyer S. Communicating risk to emergency department patients with chest pain. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(5):276–8.

Galesic M, Garcia-Retamero R, Gigerenzer G. Using icon arrays to communicate medical risks: overcoming low numeracy. Health Psychol. 2009;28(2):210–6.

Gyrd-Hansen D, Halvorsen P, Nexoe J, Nielsen J, Stovring H, Kristiansen I. Joint and separate evaluation of risk reduction: impact on sensitivity to risk reduction magnitude in the context of 4 different risk information formats. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(1):E1–10.

Hilton NZ, Carter AM, Harris GT, Sharpe AJB. Does using nonnumerical terms to describe risk aid violence risk communication? Clinician agreement and decision making. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(2):171–88.

Waters EA, Weinstein ND, Colditz GA, Emmons K. Formats for improving risk communication in medical tradeoff decisions. J Health Commun. 2006;11(2):167–82.

Brewer NT, Tzeng JP, Lillie SE, Edwards AS, Peppercorn JM, Rimer BK. Health literacy and cancer risk perception: implications for genomic risk communication. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(2):157–66.

Davis JJ. Consumers’ preferences for the communication of risk information in drug advertising: most consumers want drug side-effect information to be rich in detail and easily accessible. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):863–70.

Steiner MJ, Dalebout S, Condon S, Dominik R, Trussell J. Understanding risk: a randomized controlled trial of communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):709–17.

Carling CLL, Kristoffersen DT, Montori VM, Herrin J, Schunemann HJ, Treweek S, et al. The effect of alternative summary statistics for communicating risk reduction on decisions about taking statins: a randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000134.

Cheung YB, Wee HL, Thumboo J, Goh C, Pietrobon R, Toh HC, et al. Risk communication in clinical trials: a cognitive experiment and a survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2010;10:55.

Emmons KM, Wong M, Puleo E, Weinstein N, Fletcher R, Colditz G. Tailored computer-based cancer risk communication: correcting colorectal cancer risk perception. J Health Commun. 2004;9(2):127–41.

Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M. Communicating treatment risk reduction to people with low numeracy skills: a cross-cultural comparison. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2196–202.

Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M. Using plausible group sizes to communicate information about medical risks. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):245–50.

Graham PH, Martin RM, Browne LH. Communicating breast cancer treatment complication risks: when words are likely to fail. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2009;5(3):193–9.

Ilic D, Murphy K, Green S. Risk communication and prostate cancer: identifying which summary statistics are best understood by men. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(6):497–504.

Knapp P, Raynor DK, Woolf E, Gardner PH, Carrigan N, McMillan B. Communicating the risk of side effects to patients an evaluation of UK regulatory recommendations. Drug Saf. 2009;32(10):837–49.

Miron-Shatz T, Hanoch Y, Graef D, Sagi M. Presentation format affects comprehension and risk assessment: the case of prenatal screening. J Health Commun. 2009;14(5):439–50.

Pighin S, Savadori L, Barilli E, Rumiati R, Bonalumi S, Ferrari M, et al. Using comparison scenarios to improve prenatal risk communication. Med Decis Making. 2013;33(1):48–58.

Sheridan SL, Pignone MP, Lewis CL. A randomized comparison of patients’ understanding of number needed to treat and other common risk reduction formats. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):884–92.

Fair AKI, Murray PG, Thomas A, Cobain MR. Using hypothetical data to assess the effect of numerical format and context on the perception of coronary heart disease risk. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(4):291–6.

Dolan JG, Iadarola S. Risk communication formats for low probability events: an exploratory study of patient preferences. BMC Med Inform Decision Making. 2008;8:14.

Edwards A, Thomas R, Williams R, Ellner AL, Brown P, Elwyn G. Presenting risk information to people with diabetes: evaluating effects and preferences for different formats by a web-based randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(3):336–49.

Fortin JM, Hirota LK, Bond BE, O’Connor AM, Col NF. Identifying patient preferences for communicating risk estimates: a descriptive pilot study. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2001;1:2.

Garcia-Retamero R, Cokely ET. Effective communication of risks to young adults: using message framing and visual aids to increase condom use and STD screening. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2011;17(3):270–87.

Schapira MM, Nattinger AB, McHorney CA. Frequency or probability? A qualitative study of risk communication formats used in health care. Med Decis Making. 2001;21(6):459–67.

Sprague D, LaVallie DL, Wolf FM, Jacobsen C, Sayson K, Buchwald D. Influence of graphic format on comprehension of risk information among american indians. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):437–43.

Berry DC, Michas IC, Bersellini E. Communicating information about medication: the benefits of making it personal. Psychol Health. 2003;18(1):127–39.

Gurmankin AD, Baron J, Annstrong K. The effect of numerical statements of risk on trust and comfort with hypothetical physician risk communication. Med Decis Making. 2004;24(3):265–71.

Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Fagerlin A. Presenting research risks and benefits to parents: does format matter? Anesth Analg. 2010;111(3):718–23.

Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Fagerlin A. The effect of format on parents’ understanding of the risks and benefits of clinical research: a comparison between text, tables, and graphics. J Health Commun. 2010;15(5):487–501.

Ulph F, Townsend E, Glazebrook C. How should risk be communicated to children: a cross-sectional study comparing different formats of probability information. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2009;9:26.

Young S, Oppenheimer DM. Effect of communication strategy on personal risk perception and treatment adherence intentions. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14(4):430–42.

Fraenkel L, Wittink DR, Concato J, Fried T. Are preferences for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors influenced by the certainty effect? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(3):591–3.

Whittington D. Improving the performance of contingent valuation studies in developing countries. Environ Resour Econ. 2002;22(1–2):323–67.

Arrow K, Solow R, Portney PR, Learner EE, Radner R, Schuman H. Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. US Department of Commerce; 1993.

Adamowicz W, Louviere J, Swait J. Introduction to attribute-based stated choice methods. US Department of Commerce; 1998.

Kahneman D, Tversky A. Psychology of prediction. Psychol Rev. 1973;80(4):237–51.

Edwards A, Elwyn G. Understanding risk and lessons for clinical risk communication about treatment preferences. Qual Health Care. 2001;10:I9–13.

Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):263–91.

Spiegelhalter D, Pearson M, Short I. Visualizing uncertainty about the future. Science. 2011;333(6048):1393–400.

Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W, Kurz-Milcke E, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Helping doctors and patients make sense of health statistics. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2007;8:53–96.

Naylor CD, Chen E, Strauss B. Measured enthusiasm: does the method of reporting trial results alter perceptions of therapeutic effectiveness. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(11):916–21.

Bobbio M, Demichelis B, Giustetto G. Completeness of reporting trial results: effect on physicians’ willingness to prescribe. Lancet. 1994;343(8907):1209–11.

Sorensen L, Gyrd-Hansen D, Kristiansen IS, Nexoe J, Nielsen JB. Laypersons’ understanding of relative risk reductions: randomised cross-sectional study. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2008;8:31.

CONSORT Group. The CONSORT Statement. http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/. Accessed 8 Nov 2011.

Krupnick A, Alberini A, Cropper M, Simon N, O’Brien B, Goeree R, et al. Age, health and the willingness to pay for mortality risk reductions: a contingent valuation survey of Ontario residents. J Risk Uncertainty. 2002;24(2):161–86.

Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1436–43.

Kahneman D, Sugden R. Experienced utility as a standard of policy evaluation. Environ Resour Econ. 2005;32(1):161–81.

Weinstein MC, Shepard DS, Pliskin JS. The economic value of changing mortality probabilities: a decision-theoretic approach. Q J Econ. 1980;94(2):373–96.

Viscusi WK. A Bayesian perspective on biases in risk perception. Econ Lett. 1985;17(1–2):59–62.

Tsuchiya A, Dolan P. The QALY model and individual preferences for health states and health profiles over time: a systematic review of the literature. Med Decis Making. 2005;25(4):460–7.

Prosser LA, Wittenberg E. Do risk attitudes differ across domains and respondent types? Med Decis Making. 2007;27(3):281–7.

Prosser LA, Kuntz KM, Bar-Or A, Weinstein MC. The relationship between risk attitude and treatment choice in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Med Decis Making. 2002;22(6):506–13.

Van Houtven G, Johnson FR, Kilambi V, Hauber AB. Eliciting benefit–risk preferences and probability-weighted utility using choice-format conjoint analysis. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):469–80.

Spiegelhalter D. Quantifying uncertainty. In: Skinns L, Scott M, Cox T, editors. Risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 17–33.

Garcia-Retamero R, Galesic M, Gigerenzer G. Do icon arrays help reduce denominator neglect? Med Decis Making. 2010;30(6):672–84.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41.

Seston EM, Ashcroft DM, Griffiths CE. Balancing the benefits and risks of drug treatment: a stated-preference, discrete choice experiment with patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1175–9.

Hauber AB, Johnson FR, Grotzinger KM, Ozdemir S. Patients’ benefit-risk preferences for chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura therapies. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(3):479–88.

Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Beam C, Medjedovic J, Mauskopf J. Patient preferences and assessment of likely adherence to hepatitis C virus treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(9):619–27.

Mohamed AF, Hauber AB, Neary MP. Patient benefit-risk preferences for targeted agents in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(11):2011.

Hauber AB, Gonzalez JM, Schenkel B, Lofland JH, Martin S. The value to patients of reducing lesion severity in plaque psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2011;22(5):266–75.

Hodgkins P, Swinburn P, Solomon D, Yen L, Dewilde S, Lloyd A. Patient preferences for first-line oral treatment for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a discrete-choice experiment. Patient. 2012;5(1):33–44.

Arden NK, Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Peloso PM, Watson DJ, et al. How do physicians weigh benefits and risks associated with treatments in patients with osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom? J Rheumatol. 2012;39(5):1056–63.

Lathia N, Isogai PK, Walker SE, De AC, Cheung MC, Hoch JS, et al. Eliciting patients’ preferences for outpatient treatment of febrile neutropenia: a discrete choice experiment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):245–51.

Hauber AB, Arden NK, Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Peloso PM, Watson DJ, et al. A discrete-choice experiment of United Kingdom patients’ willingness to risk adverse events for improved function and pain control in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(2):289–97.

Aristides M, Weston AR, Fitzgerald P, Le RC, Maniadakis N. Patient preference and willingness-to-pay for Humalog Mix25 relative to Humulin 30/70: a multicountry application of a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2004;7(4):442–54.

Guimaraes C, Marra CA, Colley L, Gill S, Simpson SH, Meneilly GS, et al. A valuation of patients’ willingness-to-pay for insulin delivery in diabetes. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;3:359–66.

Howard K, Salkeld G, Pignone M, Hewett P, Cheung P, Olsen J, et al. Preferences for CT colonography and colonoscopy as diagnostic tests for colorectal cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2011;14(8):1146–52.

Faggioli G, Scalone L, Mantovani LG, Borghetti F, Stella A. PREFER study group. Preferences of patients, their family caregivers and vascular surgeons in the choice of abdominal aortic aneurysms treatment options: the PREFER study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42(1):26–34.

Gidengil C, Lieu TA, Payne K, Rusinak D, Messonnier M, Prosser LA. Parental and societal values for the risks and benefits of childhood combination vaccines. Vaccine. 2012;30(23):3445–52.

Augustovski F, Beratarrechea A, Irazola V, Rubinstein F, Tesolin P, Gonzalez J, et al. Patient preferences for biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a discrete-choice experiment. Value Health. 2013;16(2):385–93.

Bryan S, Buxton M, Sheldon R, Grant A. Magnetic resonance imaging for the investigation of knee injuries: an investigation of preferences. Health Econ. 1998;7(7):595–603.

Bryan S, Roberts T, Heginbotham C, McCallum A. QALY-maximisation and public preferences: results from a general population survey. Health Econ. 2002;11(8):679–93.

Bishop AJ, Marteau TM, Armstrong D, Chitty LS, Longworth L, Buxton MJ, et al. Women and health care professionals’ preferences for Down’s syndrome screening tests: a conjoint analysis study. BJOG. 2004;111(8):775–9.

Lewis SM, Cullinane FM, Carlin JB, Halliday JL. Women’s and health professionals’ preferences for prenatal testing for Down syndrome in Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46(3):205–11.

Lewis SM, Cullinane FN, Bishop AJ, Chitty LS, Marteau TM, Halliday JL. A comparison of Australian and UK obstetricians’ and midwives’ preferences for screening tests for Down syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(1):60–6.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Essink-Bot ML, Meerding WJ, Pols HA, Koes BW, Steyerberg EW. Patients’ preferences for osteoporosis drug treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Osteoporos Int. 2008;7:1029–37.

Bunge EM, de Bekker-Grob EW, van Biezen FC, Essink-Bot ML, de Koning HJ. Patients’ preferences for scoliosis brace treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Spine. 2010;35(1):57–63.

Watson V, Ryan M, Watson E. Valuing experience factors in the provision of Chlamydia screening: an application to women attending the family planning clinic. Value Health. 2009;12(4):621–3.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Essink-Bot ML, Meerding WJ, Koes BW, Steyerberg EW. Preferences of GPs and patients for preventive osteoporosis drug treatment: a discrete-choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(3):211–9.

Kruijshaar ME, Essink-Bot ML, Donkers B, Looman CW, Siersema PD, Steyerberg EW. A labelled discrete choice experiment adds realism to the choices presented: preferences for surveillance tests for Barrett esophagus. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:31.

Hol L, de Bekker-Grob EW, van Dam L, Donkers B, Kuipers EJ, Habbema JD, et al. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening strategies: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(6):972–80.

Wirostko B, Beusterien K, Grinspan J, Ciulla T, Gonder J, Barsdorf A, et al. Patient preferences in the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:229–37.

Flood EM, Ryan KJ, Rousculp MD, Beusterien KM, Divino VM, Block SL, et al. Parent preferences for pediatric influenza vaccine attributes. Clin Pediatr. 2011;50(4):338–47.

Damman OC, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Hendriks M. Creating compact comparative health care information: what are the key quality attributes to present for cataract and total hip or knee replacement surgery? Med Decis Making. 2012;32(2):287–300.

Tong BC, Huber JC, Ascheim DD, Puskas JD, Ferguson TB Jr, Blackstone EH, et al. Weighting composite endpoints in clinical trials: essential evidence for the heart team. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(6):1908–13.

Sung L, Alibhai SM, Ethier MC, Teuffel O, Cheng S, Fisman D, et al. Discrete choice experiment produced estimates of acceptable risks of therapeutic options in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(6):627–34.

Marang-vandeMheen PJ, Elsinga J, Otten W, Versluijs M, Smeets HJ, Vree R, et al. The relative importance of quality of care information when choosing a hospital for surgical treatment: a hospital choice experiment. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(6):816–27.

Watson V, Carnon A, Ryan M, Cox D. Involving the public in priority setting: a case study using discrete choice experiments. J Public Health. 2012;34(2):253–60.

Bijlenga D, Bonsel GJ, Birnie E. Eliciting willingness to pay in obstetrics: comparing a direct and an indirect valuation method for complex health outcomes. Health Econ. 2011;20(11):1392–406.

Bijlenga D, Birnie E, Mol BW, Bonsel GJ. Obstetrical outcome valuations by patients, professionals, and laypersons: differences within and between groups using three valuation methods. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:93.

Palumbo A, De La FP, Rodriguez M, Sanchez F, Martinez-Salazar J, Munoz M, et al. Willingness to pay and conjoint analysis to determine women’s preferences for ovarian stimulating hormones in the treatment of infertility in Spain. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1790–8.

Muhlbacher AC, Nubling M. Analysis of physicians’ perspectives versus patients’ preferences: direct assessment and discrete choice experiments in the therapy of multiple myeloma. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12(3):193–203.

Manjunath R, Yang JC, Ettinger AB. Patients’ preferences for treatment outcomes of add-on antiepileptic drugs: a conjoint analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24(4):474–9.

Kinsler JJ, Cunningham WE, Nurena CR, Nadjat-Haiem C, Grinsztejn B, Casapia M, et al. Using conjoint analysis to measure the acceptability of rectal microbicides among men who have sex with men in four South American cities. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1436–47.

King MT, Viney R, Smith DP, Hossain I, Street D, Savage E, et al. Survival gains needed to offset persistent adverse treatment effects in localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(4):638–45.

Burnett HF, Regier DA, Feldman BM, Miller FA, Ungar WJ. Parents’ preferences for drug treatments in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a discrete choice experiment. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(9):1382–91.

Bridges JF, Mohamed AF, Finnern HW, Woehl A, Hauber AB. Patients’ preferences for treatment outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a conjoint analysis. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):224–31.

Lee SJ, Newman PA, Comulada WS, Cunningham WE, Duan N. Use of conjoint analysis to assess HIV vaccine acceptability: feasibility of an innovation in the assessment of consumer health-care preferences. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(4):235–41.

Wittink MN, Morales KH, Cary M, Gallo JJ, Bartels SJ. Towards personalizing treatment for depression: developing treatment values markers. Patient. 2013;6(1):35–43.

Zimmermann TM, Clouth J, Elosge M, Heurich M, Schneider E, Wilhelm S, et al. Patient preferences for outcomes of depression treatment in Germany: a choice-based conjoint analysis study. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:210–9.

Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Hauber AB, Lescrauwaet B, Masterson A. Physicians’ stated trade-off preferences for chronic hepatitis B treatment outcomes in Germany, France, Spain, Turkey, and Italy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(4):419–26.

Petrou S, McIntosh E. Women’s preferences for attributes of first-trimester miscarriage management: a stated preference discrete-choice experiment. Value Health. 2009;12(4):551–9.

Sadique MZ, Devlin N, Edmunds WJ, Parkin D. The effect of perceived risks on the demand for vaccination: results from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e54149.

Aristides M, Chen J, Schulz M, Williamson E, Clarke S, Grant K. Conjoint analysis of a new chemotherapy: willingness to pay and preference for the features of raltitrexed versus standard therapy in advanced colorectal cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;11:775–84.

Watson V, Ryan M, Brown CT, Barnett G, Ellis BW, Emberton M. Eliciting preferences for drug treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172(6 Pt 1):2321–5.

Fraenkel L, Constantinescu F, Oberto-Medina M, Wittink DR. Women’s preferences for prevention of bone loss. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(6):1086–92.

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink DR. Preference for hip protectors among older adults at high risk for osteoporotic fractures. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(10):2064–8.

Goto R, Nishimura S, Ida T. Discrete choice experiment of smoking cessation behaviour in Japan. Tobacco Control. 2007;16(5):336–43.

Acknowledgments

Professor Katherine Payne was part funded by a Research Councils UK (RCUK) Academic Fellowship between September 2007 and September 2012. No other sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript. Caroline Vass is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research Studentship. Mark Harrison, Dan Rigby, Caroline Vass, Terry Flynn, Jordan Louviere, and Katherine Payne have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. The authors are grateful to Mary Ingram, Lawrence Library, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, University of Manchester, for assistance in developing the electronic search strategies for both reviews, and to Stuart Wright, Manchester Centre for Health Economics, for double screening the abstract lists for inclusion in this review.

Contributions to authorship

Mark Harrison, Katherine Payne, Terry Flynn, Jordan Louviere and Dan Rigby conceived the idea for this study and produced the protocol which informed the systematic search strategy. Mark Harrison and Katherine Payne applied the inclusion criteria and screening of abstracts, and extracted data from the included studies. Caroline Vass conducted the rapid review. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Katherine Payne acts as the overall guarantor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrison, M., Rigby, D., Vass, C. et al. Risk as an Attribute in Discrete Choice Experiments: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Patient 7, 151–170 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0048-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0048-1