Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare the acceptability, validity and concordance of discrete choice experiment (DCE) and best–worst scaling (BWS) stated preference approaches in health.

Methods

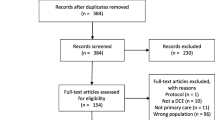

A systematic search of EMBASE, Medline, AMED, PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and EconLit databases was undertaken in October to December 2016 without date restriction. Studies were included if they were published in English, presented empirical data related to the administration or findings of traditional format DCE and object-, profile- or multiprofile-case BWS, and were related to health. Study quality was assessed using the PREFS checklist.

Results

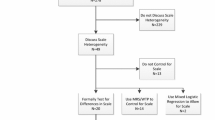

Fourteen articles describing 12 studies were included, comparing DCE with profile-case BWS (9 studies), DCE and multiprofile-case BWS (1 study), and profile- and multiprofile-case BWS (2 studies). Although limited and inconsistent, the balance of evidence suggests that preferences derived from DCE and profile-case BWS may not be concordant, regardless of the decision context. Preferences estimated from DCE and multiprofile-case BWS may be concordant (single study). Profile- and multiprofile-case BWS appear more statistically efficient than DCE, but no evidence is available to suggest they have a greater response efficiency. Little evidence suggests superior validity for one format over another. Participant acceptability may favour DCE, which had a lower self-reported task difficulty and was preferred over profile-case BWS in a priority setting but not necessarily in other decision contexts.

Conclusion

DCE and profile-case BWS may be of equal validity but give different preference estimates regardless of the health context; thus, they may be measuring different constructs. Therefore, choice between methods is likely to be based on normative considerations related to coherence with theoretical frameworks and on pragmatic considerations related to ease of data collection.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1697.

Cheung KL, Wijnen BF, Hollin IL, Janssen EM, Bridges JF, Evers SMAA, Hiligsmann M. Using best–worst scaling to investigate preferences in health Care. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34:1195–209.

Whitty JA, Lancsar E, Rixon K, Golenko X, Ratcliffe J. A systematic review of stated preference studies reporting public preferences for healthcare priority setting. Patient. 2014;7(4):365–86.

Whitty JA, Ratcliffe J, Kendall E, Burton P, Wilson A, Littlejohns P, et al. Prioritising patients for bariatric surgery: building public preferences from a discrete choice experiment into public policy. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e008919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008919.

Marsh K, Ijzerman M, Thokala P, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kalo Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—emerging good practices: report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(2):125–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.016.

Thokala P, Devlin N, Marsh K, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kalo Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—an introduction: report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.003.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Nord E, Street A, Richardson J, Kuhse H, Singer P. The significance of age and duration of effect in social evaluation of health care. Health Care Anal. 1996;4(2):103–11.

Olsen JA, Donaldson C. Helicopters, hearts and hips: using willingness to pay to set priorities for public sector health care programmes. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(1):1–12.

Ryan M, Scott DA, Reeves C, Bate A, van Teijlingen ER, Russell EM, et al. Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(5):1–186.

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2014;32(9):883–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x.

Thurstone LL. A law of comparative judgment. Psychol Rev. 1994;101(2):266–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.2.266.

McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press; 1974.

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN. Using best–worst scaling choice experiments to measure public perceptions and preferences for healthcare reform in Australia. Patient. 2010;3(4):275–83.

Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. 1966;74:132–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/259131.

Whitty JA, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Scuffham PA. Australian public preferences for the funding of new health technologies: a comparison of discrete choice and profile case best–worst scaling methods. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(5):638–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x14526640.

Finn A, Louviere JJ. Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: the case of food safety. J Public Policy Mark. 1992;11(1):12–5.

Louviere JJ, Woodworth GG. Best–worst scaling: a model for largest difference judgments, Working Paper. Faculty of Business, University of Alberta; 1990.

Marley AAJ, Louviere JJ. Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best–worst choices. J Math Psychol. 2005;49(6):464–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmp.2005.05.003.

Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best–worst scaling: theory, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

Flynn TN. Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: recent developments in three types of best–worst scaling. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.10.29.

Cheung KL, Wijnen BF, Hollin IL, Janssen EM, Bridges JF, Evers SM, et al. Using best–worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(12):1195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0429-5.

Ratcliffe J, Flynn T, Terlich F, Stevens K, Brazier J, Sawyer M. Developing adolescent-specific health state values for economic evaluation: an application of profile case best–worst scaling to the child health utility 9D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(8):713–27. https://doi.org/10.2165/11597900-000000000-00000.

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:458–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X10381280.

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Estimating preferences for a dermatology consultation using Best–Worst Scaling: comparison of various methods of analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-76.

Yoo HI, Doiron D. The use of alternative preference elicitation methods in complex discrete choice experiments. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1166–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.09.009.

Coast J, Flynn TN, Natarajan L, Sproston K, Lewis J, Louviere JJ, et al. Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):874–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.015.

Coast J, Salisbury C, de Berker D, Noble A, Horrocks S, Peters TJ, et al. Preferences for aspects of a dermatology consultation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(2):387–92.

Cameron MP, Newman PA, Roungprakhon S, Scarpa R. The marginal willingness-to-pay for attributes of a hypothetical HIV vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31(36):3712–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.089.

Lancsar E, Louviere J, Donaldson C, Currie G, Burgess L. Best worst discrete choice experiments in health: methods and an application. Soc Sci Med. 2013;76(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.007.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

Louviere J, Lings I, Islam T, Gudergan S, Flynn T. An introduction to the application of (case 1) best–worst scaling in marketing research. Int J Res Mark. 2013;30(3):292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.10.002.

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best–worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171–89.

Krucien N, Watson V, Ryan M. Is best–worst scaling suitable for health state valuation? A comparison with discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3459.

Mühlbacher AC, Bethge S. Patients’ preferences: a discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(6):657–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0622-4.

Johnson RF, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223.

Lancsar E, Swait J. Reconceptualising the external validity of discrete choice experiments. PharmacoEconomics. 2014;32(10):951–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0181-7.

Mas-Colell A, Green JR. Microeconomic theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, Purnell TS, Bridges JFP. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. PharmacoEconomics. 2013;31(10):877–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0089-7.

Whitty JA, Walker R, Golenko X, Ratcliffe J. A think aloud study comparing the validity and acceptability of discrete choice and best worst scaling methods. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e90635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090635.

Netten A, Burge P, Malley J, Potoglou D, Towers AM, Brazier J, Flynn T, Forder J, Wall B. Outcomes of social care for adults: Developing a preference-weighted measure. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(16):1–166.

Potoglou D, Burge P, Flynn T, Netten A, Malley J, Forder J, Brazier J. Best–worst scaling vs. discrete choice experiments: an empirical comparison using social care data. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1717–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.027.

Coast J, Huynh E, Kinghorn P, Flynn T. Complex valuation: applying ideas from the complex intervention framework to valuation of a new measure for end-of-life care. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(5):499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0365-9.

Flynn TN, Peters TJ, Coast J. Quantifying response shift or adaptation effects in quality of life by synthesising best–worst scaling and discrete choice data. J Choice Model. 2013;6:34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocm.2013.04.004.

Hollin IL, Peay HL, Bridges JF. Caregiver preferences for emerging duchenne muscular dystrophy treatments: a comparison of best–worst scaling and conjoint analysis. Patient. 2014;8(1):19–27.

Janssen EM, Segal JB, Bridges JF. A framework for instrument development of a choice experiment: an application to type 2 diabetes. Patient. 2016;9(5):465–79.

Severin F, Schmidtke J, Muhlbacher A, Rogowski WH. Eliciting preferences for priority setting in genetic testing: a pilot study comparing best–worst scaling and discrete-choice experiments. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(11):1202–8.

van Dijk JD, Groothuis-Oudshoom CGM, Marshall DA, Ijzerman MJ. An empirical comparison of discrete choice experiment and best–worst scaling to estimate stakeholders’ risk tolerance for hip replacement surgery. Value Health. 2016;19(4):316–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.020.

Xie F, Pullenayegum E, Gaebel K, Oppe M, Krabbe PF. Eliciting preferences to the EQ-5D-5L health states: discrete choice experiment or multiprofile case of best–worst scaling? Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(3):281–8.

Weernink MG, Groothuis-Oudshoom CG, Ijzerman MJ, van Til JA. Valuing treatments for Parkinson disease incorporating process utility: performance of best–worst scaling, time trade-off, and visual analogue scales. Value Health. 2016;19(2):226–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.11.011.

Ryan M, Watson V, Entwistle V. Rationalising the ‘irrational’: a think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009;18:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1369.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Deleting ‘irrational’ responses from discrete choice experiments: a case of investigating or imposing preferences? Health Econ. 2006;15:797–811. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1104.

Whitty JA, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Scuffham PA. Australian public preferences for the funding of new health technologies: a comparison of discrete choice and profile case best–worst scaling methods. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:638–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X14526640.

Stafinski T, Menon D, Philippon DJ, McCabe C. Health technology funding decision-making processes around the world: the same, yet different. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(6):475–95. https://doi.org/10.2165/11586420-000000000-00000.

Yoongthong W, Hu S, Whitty JA, Wibulpolprasert S, Sukantho K, Thienthawee W, et al. National drug policies to local formulary decisions in Thailand, china, and australia: drug listing changes and opportunities. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S126–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.003.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. Valuing health states: a comparison of methods. J Health Econ. 1996;15(2):209–31.

Arnold D, Girling A, Stevens A, Lilford R. Comparison of direct and indirect methods of estimating health state utilities for resource allocation: review and empirical analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2688. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2688.

Muhlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Zweifel P, Johnson FR. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best–worst scaling: an overview. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):1–14.

Louviere JJ, Lancsar E. Choice experiments in health: the good, the bad, the ugly and toward a brighter future. Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4(4):527–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133109990193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sofia Gonçalves performed the searches, screened and extracted papers, assessed study quality, drafted the review, and approved the final version of the review prior to submission. Jennifer Whitty coordinated and edited the review, reviewed papers for inclusion, made an intellectual contribution, approved the final version of the review prior to submission and is the guarantor of the review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JW has previously published both DCE and BWS studies in this field. The authors are not aware of any potential conflicts of interest related to the review.

Sources of funding

No funding support was received for this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitty, J.A., Oliveira Gonçalves, A.S. A Systematic Review Comparing the Acceptability, Validity and Concordance of Discrete Choice Experiments and Best–Worst Scaling for Eliciting Preferences in Healthcare. Patient 11, 301–317 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0288-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0288-y