Abstract

Background and Objective

Several medication adherence patient-reported outcome measures (MA-PROMs) are available for use in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, little evidence is available on the most suitable MA-PROM to measure medication adherence in patients with CVD. The aim of this systematic review is to synthesise the measurement properties of MA-PROMs for patients with CVD and identify the most suitable MA-PROM for use in clinical practice or future research in patients with CVD.

Methods

An electronic search of nine databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, ProQuest Health and Medicine, Cochrane Library, PsychInfo, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science) was conducted to identify studies that have reported on at least one of the measurement properties of MA-PROMs in patients with CVD. The methodological quality of the studies included in the systematic review was evaluated using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist.

Results

A total of 40 MA-PROMs were identified in the 84 included studies. This review found there is a lack of moderate-to-high quality evidence of sufficient content validity for all MA-PROMs for patients with CVDs. Only eight MA-PROMs were classified in COSMIN recommendation category A. They exhibited sufficient content validity with very low-quality evidence, and moderate-to-high quality evidence for sufficient internal consistency. The 28 MA-PROMs that meet the requirements for COSMIN recommendation category ‘B’ require further validation studies. Four MA-PROMs including Hill–Bone Compliance Medication Scale (HBMS), the five-item Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5), Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH), and MUAH-16 have insufficient results with high quality evidence for at least one measurement property and consequently are not recommended for use in patients with CVD. Two MA-PROMs (Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale [ARMS] and ARMS-7) are comprehensive and have moderate to high quality evidence for four sufficient measurement properties.

Conclusion

From the eight MA-PROMs in COSMIN recommendation category A, ARMS and ARMS-7 were selected as the most suitable MA-PROMs for use in patients with CVD. They are the most comprehensive with be best quality evidence to support their use in clinical practice and research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This systematic review used COSMIN guidelines to provide synthesised evidence on the measurement properties of MA-PROMs for patients with CVD. |

ARMS and ARMS-7 were selected as the most suitable PROMs from the eight identified MA-PROMs (ABQ, ARMS, ARMS-7, MAS, MASES-R, MEDS, MTQ-Purposeful action, and SEAMS) for patients with CVD. |

The findings of this review could assist healthcare providers and researchers to select the most suitable PROM to evaluate adherence to medication for CVD in their context. |

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a major public health burden that is impacting on sustainable human development [1]. Worldwide, it is estimated that CVDs affect 422 million people, making them the leading cause of death globally, with an estimated one-third of all death attributed to CVDs [2]. Of these global deaths, in excess of 75% occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [3]. To reduce the risk of developing CVDs, behavioural changes, such as cessation of cigarette smoking, reducing harmful use of alcohol, increased physical activity and a healthy diet, are recommended [4]. In patients with either established CVD or those who are at higher risk for future CVDs, long-term medication usage is required [5], and it is reported that more than half the patients with chronic diseases do not take their medications as prescribed (low medication adherence) [6].

Medication adherence is a complex phenomenon affected by multiple factors. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour—taking medication, following a diet or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” [6, p.3]. There is growing evidence that taking medications as prescribed is linked with better clinical, humanistic and economical outcomes [7]. In patients with CVD, non-adherence could lead to a failure to control disease symptoms, higher risk of future cardiovascular complications, preventable hospital readmissions or early death [8, 9].

Under-utilisation of medications has an economic impact as significant resources are wasted due to healthcare-related costs associated with hospital admissions, readmissions and/or complications occurring when medication is under-utilised [7]. It has been estimated that sub-optimal use of medications resulted in unnecessary costs of US$475B per annum worldwide and non-adherence is considered to contribute 57% (US$269B) of these unnecessary costs [10]. It has been found that medication adherence in patients with congestive heart failure and hypertension reduced average annual total health care spending per individual by US$7823 and US$3908, respectively [11]. Appropriate interventions should be designed to improve medication adherence, thereby promoting better health and reducing wastage of health-care resources [12].

Interventions to improve medication adherence have only demonstrated limited effectiveness in previous research [7, 13]. This could be because the interventions did not necessarily consider multiple facets of non-adherence and were not individualised at the patient level to consider specific reasons for non-adherence, such as intentional or non-intentional non-adherence [14]. Improving medication adherence begins with a valid and reliable assessment of medication adherence through appropriate consideration of the reasons for, and the level of, any non-adherence prior to choosing an appropriate intervention [15].

Currently, there is no consensus on a universal method of adherence measurement and there has been debate over a ‘gold standard’ for measuring adherence [16]. According to the WHO, medication adherence measures are classified into two categories: objective measures and subjective measures [6]. Objective measures of medication adherence are considered to be more reliable and accurate than subjective methods [6, 17], and may include approaches such as electronic monitoring, pharmacy and/or other health-care provider records, pill counts, or biochemical measures. However, objective measures may involve additional costs and the procedures require more time than routine clinical practice allows [17]. Subjective measures involve approaches such as self-report and healthcare provider assessment [6].

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are self-report instruments designed to capture information on patients-reported outcomes (PROs) [18,19,20]. Patient-reported outcomes are defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else” [21], and PROMs are used to collect these data for healthcare decision making [22]. Patient-reported outcomes provide patients’ perspectives on their health condition or health behaviour. Medication-taking behaviour is one of the PROs that could be evaluated in clinical practice and research to inform medication adherence support, treatment benefits or harms, and be used as a proxy indicator of clinical progress, disease complications, hospital admissions, healthcare costs and death [6, 20, 23]. Patient-reported outcome measures are the most extensively used measure of medication adherence, primarily because they are relatively inexpensive, easy to undertake, take a short amount of time, and are less invasive than objective measures. Medication adherence PROMs (MA-PROMs) may use questions about the extent of non-adherence or reasons for non-adherence [15], and can be used in large population samples. Patient-reported outcome measures have two main weaknesses, recall and social desirability bias, which may result in overestimation of adherence [15,16,17]. Medication adherence patient-reported outcome measures should be of sufficient quality to ensure that the results are representative; therefore, the most suitable PROM with evidence of reliability, validity, and comprehensiveness should be selected [15].

A number of different MA-PROMs are available for public use to assess medication adherence for patients with CVDs, and each of these cover a range of methods, domains and measurement properties [24,25,26]. Owing to the vulnerability of PROMs to overestimation, identifying the most suitable PROM requires a rigorous assessment with standardised guidelines. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) group established an international consensus-based taxonomy terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for PROMs [27]. With the clinical utility becoming one of the critical features of PROMs integrated into clinical practice and research [28], clinical utility should be taken into account during selection of suitable PROMs [29]. The term “feasibility” is used in the COSMIN guidelines to refer to clinical utility suggesting that feasibility applies to PROMs, whereas clinical utility is more related to an intervention [29,30,31]. In this review, feasibility (clinical utility) is used to evaluate whether a MA-PROM can be applied easily for the intended context of use (i.e., for evaluation of initiation, implementation or discontinuation phases of medication adherence in people with CVD) considering the constraints of time or cost [29, 32]. Completion time, copyright issue, length of PROM, type and method of administration were included as elements of feasibility in the selection of the MA-PROMs [29, 31].

The purpose of this project was to undertake a systematic review of the available MA-PROMs for people with CVD, evaluate their quality and feasibility, and to decide if they are adequate for purpose; could be improved; or if an entirely new MA-PROM is required. A preliminary search was conducted in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, and no systematic reviews were found on the quality of MA-PROMs in CVD.

2 Methods

This systematic review used the COSMIN guidelines to evaluate the measurement properties of MA-PROMs [29, 31, 33, 34] and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [35]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42019124291) and published in JBI Evidence Synthesis [36].

The search strategy for this systematic review followed a priori published protocol [36], the three-step method was used [37] and COSMIN guided the choice of major concepts [29]. The main concepts were generated based on Population (patients aged ≥ 18 years with CVD, i.e., hypertension, dyslipidaemia, congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease or stroke either alone or with other diseases). Instrument (any PROM), Construct (at least one of the three phases of medication adherence (initiation, implementation or discontinuation) and Outcome (at least one of the following measurement properties: content validity, structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance, reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, hypothesis testing for construct validity or responsiveness). The authors used the sensitive search filter for measurement properties developed by Terwee et al. [38].

Nine databases including PubMed, ProQuest Health and Medicine, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus were searched from inception to Dec 31, 2021. Forward citation tracking was conducted from databases to include additional articles. All articles published in any language were included with no date limit. Non-English studies were included until data extraction to acknowledge their existence and a possible language bias [29].

The authors included studies of any study design that reported on the measurement properties of MA-PROMs among adults with CVD. Based on the COSMIN guidelines [29] studies that used a PROM only to measure outcomes or to validate other PROMs as a comparator, were excluded. Three levels of screening were performed, namely title screening, abstract screening and full-text screening using EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA). Two reviewers (HGT and JS, SW or ETE) independently screened the titles then abstracts of articles for eligibility for further evaluation. Full-text articles were obtained and independently reviewed by two authors (HGT and JS, SW or ETE) to confirm if the article met the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The process of identifying relevant articles was reported in a PRISMA flow chart [39]. The inclusion criteria and operational definitions based on COSMIN guidelines on measurement properties [27] were described in detail in a priori published protocol [36].

Data were extracted from articles included in the review using data-extraction tools guided by the COSMIN checklist [31]. The data-extraction tools were pilot tested on five randomly selected studies. The pilot study was conducted by two authors until both authors (HGT and JS) were able to record all identified relevant information and were both in agreement. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer (HGT) and cross-checked by a second reviewer (JS, SW or ETE). Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the authors.

The nominated corresponding author of an article was contacted to request missing information when necessary. If authors did not respond, the requested information was reported as “unknown”.

Descriptive statistics were used for the general characteristics of the studies and MA-PROMs. The data from the included studies were synthesised using tables for the risk of bias, and results of measurement properties. The adherence domain(s) that each MA-PROM measured were described using Medication Adherence Model (MAM), which depicts both intentional and unintentional reasons for non-adherence [40]. Medication Adherence Model has nine domains for non-adherence, three related to each of unintentional reasons (Pattern Behaviour), intentional reasons (Purposeful Action) and Feedback [40]. In this review, a MA-PROM is said to be comprehensive if the items of the PROM capture information on the extent of both medication-taking and prescription filling and at least two domains each from intentional reasons (Pattern Behaviour) and unintentional reasons for non-adherence (Purposeful Action and Feedback) in the MAM framework (Table 2).

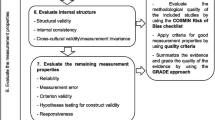

Ten COSMIN boxes containing standards were used to evaluate risk of bias/methodological quality of studies on PROM development (COSMIN box 1), content validity (COSMIN box 2) and eight other measurement properties (COSMIN boxes 3 to 10) [29, 31, 34]. The methodological quality for each measurement property and study, including PROM development studies, was evaluated and an overall rating score given for each PROM using COSMIN scoring [34, 41]. The quality of evidence was graded as high; moderate; low; or very low for the overall ratings using a modified GRADE approach for content validity [29, 34]. For PROMs with inadequate quality of development study, and inadequate quality or no content validity studies, the quality of evidence for content validity was obtained from reviewer’s ratings and graded as “very low” [34]. The risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, and indirectness were considered to downgrade quality of evidence [29].

2.1 Formulating Recommendations for the Use of MA-PROMs in Patients with CVD

To select the most suitable MA-PROM for evaluation of medication adherence for people with CVD, recommendations were generated in relation to both the construct (medication adherence) and target population (patients with CVD) based on the methodological quality and sufficiency of results. Three categories of recommendations based on COSMIN guideline were used for this review [29].

-

A.

Patient-reported outcome measures with any level of evidence for sufficient content validity AND at least low-quality evidence for sufficient internal consistency.

-

B.

Patient-reported outcome measures categorised not in A or C.

-

C.

Patient-reported outcome measures with high-quality evidence for an insufficient measurement property

We can recommend MA-PROMs in category ‘A’ for use in the evaluation of medication adherence in patients with CVD, as these MA-PROMs can be seen trusted. There is a potential to use MA-PROMs in category ‘B’, but further validation study is required to evaluate the quality of these MA-PROMs. Medication adherence PROMs of category C should not be recommended for use. COSMIN guidelines suggest that if no PROMs from category ‘A’ are identified and only PROMs from category ‘B’ are available, the PROM with best evidence on sufficient content validity can be recommended on a preliminary basis, until further evidence is obtained [31].

The COSMIN guideline recommends selecting the most suitable PROM from category “A” [29]. Further comparison of these PROMs was performed based on additional measurement properties, other than content validity and internal consistency, with the best evidence. Finally, contexts and feasibility aspects were considered to select the most suitable MA-PROM for people with CVD.

3 Results

The search strategy identified 8691 records. After removal of duplicates, title/abstract and full test screening processes, 69 records met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Five articles using backward citation tracking from the reference list, and 10 articles with forward citation tracking were included, resulting in a final sample of 84 articles. A PRISMA flow-diagram of the search procedures and results is provided in Fig. 1.

The study characteristics of the 84 included articles [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125], each reporting a unique study, are presented in Supplementary data, Table S1. Of these, nine studies [47, 51, 65, 66, 78, 80, 118, 119, 125] evaluated two MA-PROMs simultaneously, whereas one study [85] included three MA-PROMs. The largest number of studies were conducted in the USA (26/84). Only two studies were undertaken in Africa [85, 99]. English was the most common target language for MA-PROMs within the studies (n = 31, 37%), while there were seven studies in Chinese, six studies in Persian, five each in Brazilian Portuguese, German, and Turkish, four studies in Arabic, three each in Korean, Polish and Spanish, and two in European Portuguese. The MA-PROM language was not described in five studies conducted in Brazil (3), Denmark (1), and India (1). Other eight MA-PROM languages were used once as a target language for the MA-PROM, including Czech, French, Kannada, Malay, Runyankore/Rukiga, Thai language and Xhosa. The most common study setting was hospital-outpatient services (n = 39, 46%). Patients with a single specific disease were recruited in 76% of the studies (n = 64), of which 48 studies (75%) included patients with hypertension. Nearly 95% (n = 80) of the included studies employed a cross-sectional design to evaluate MA-PROMs for their measurement properties.

Forty separate MA-PROMs were evaluated by the 84 studies included in this review. Of the 40 MA-PROMs, the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) (n = 18) was the most frequently evaluated MA-PROM, followed by Morisky Green Levine Scale (MGLS) (n = 8). Characteristics for all included MA-PROMs are provided in Table 1. Most MA-PROMs (n = 32, 78%) were generic measures of medication adherence, and 8 were specific to hypertension [51, 71, 77, 85, 89, 103, 110, 121]. None of the included MA-PROMs evaluated all three phases of medication adherence. Almost all MA-PROMs had items that evaluated the implementation phase (39/40), while 20 MA-PROMs had items dealing with the discontinuation phase. No MA-PROMs had items related to the initiation phase of medication adherence.

The MA-PROMs included between 1 and 28 items [66, 89, 105, 125] and most (35/40) used a Likert scale, with between 3 and 10 points, as a response format for their items. A recall period, from 1 day [50, 95, 103] to 1 year, [103] was specified in 14 of the included MA-PROMs. A combination of different recall periods was used within six MA-PROMs [47, 50, 56, 92, 93, 103] . The recall period for VAS varied across studies [66, 125].

Medication adherence patient-reported outcome measures may have licensing information and cost to use. Two MA-PROMs are licensed and subject to charge [95, 97]. Six MA-PROMs are in the public domain [65, 66, 96, 98, 102, 105, 125] while 12 MA-PROMs are free of charge provided that the specific conditions are met [45, 81, 92, 93, 103, 114, 119, 121].

The included MA-PROMs were classified into three groups based on the information that items asked about. Group-1: items about the extent of non-adherence only [60, 66, 105, 119, 125]. Group-2: items about reasons for non-adherence (intentional, unintentional reasons or both). Ten asked about both intentional and unintentional reasons for non-adherence [51, 71, 86, 96, 97, 102, 116, 119, 121, 122]. Two asked about intentional reasons only [74, 120] and one [73] asked about unintentional reasons only. Group-3: items asks about both the extent of, and reasons for, non-adherence [45, 50, 54,55,56, 65, 67, 77, 78, 81, 85, 89, 91,92,93, 95, 98, 103, 110, 113, 114, 117, 126]. Six MA-PROMs [50, 54, 81, 92, 93, 98] in Group-3 were comprehensive enough to capture information on the extent of both medication-taking and prescription-filling and at least two additional domains from both intentional and unintentional reasons for non-adherence from the MAM framework [40] (Table 2).

3.1 Evaluating the Measurement Properties of MA-PROMs in CVD

3.1.1 Overall Content Validity

Patient-reported outcome measures development was rated for the 24 original MA-PROMs [45, 60, 77, 78, 81, 86, 89, 96, 97, 102, 103, 105, 113, 114, 116, 119,120,121,122, 127,128,129,130] and 13 MA-PROMs [46, 50, 51, 53,54,55,56, 65, 67, 70, 80, 85, 92, 95, 110, 117] were modified versions of the original MA-PROMs. Patient-reported outcome measures development was not rated for 3 MA-PROMs [66, 71, 91, 125], the development studies for two were published in a language other than English [71, 91], and a development study could not be found for one [66]. However, all three of these original MA-PROMs were included in this review because their measurement properties had been evaluated among people with CVD.

The quality PROM development was obtained from PROM design (concept elicitation) and cognitive interview studies (Table 3). The concept elicitation for 21 MA-PROMs did not involve patients in their development and was therefore deemed inadequate [45, 50, 56, 60, 77, 78, 81, 97, 102, 103, 105, 113, 114, 119, 120, 122, 126]. The concept elicitation for one study [98] was rated very good as patients representative of the target population were involved in a qualitative study [130] of very good quality. The concept elicitation was of adequate quality for four MA-PROMs because items were generated from a sample representing the target population using a qualitative study of adequate quality [86, 119, 128, 129].

Cognitive interviews with patients were reported for the development of ten original MA-PROMs [45, 60, 77, 81, 102, 113, 116, 119, 121, 122]. Cognitive interviews were rated doubtful for all of these MA-PROMs because at least one of the standards for cognitive interviews was rated doubtful. The overall quality of PROM development was rated inadequate for most of the MA-PROMs (32/40). Only two had doubtful quality on the overall PROM development, both having doubtful quality for both concept elicitation and cognitive interview parts [116, 121].

Of the 35 studies that evaluated the content validity of an existing MA-PROM, 21 involved only patients [42, 44, 47, 52, 55, 59, 61, 62, 68, 70, 72, 75, 76, 79, 84, 88, 90, 99, 109, 115, 131], 4 involved only experts [67, 89, 103, 124], and 10 involved both patients and experts [46, 54, 63, 64, 73, 74, 86, 108, 117, 123] (Table 4). No studies that were not development studies were found on content validity for 21 of the identified MA-PROMs [45, 50, 51, 56, 60, 66, 71, 78, 80, 85, 91,92,93, 96, 97, 105, 110, 113, 119,120,121, 125]. All 31 content validity studies involving patients were of doubtful quality for relevance and comprehensibility, and none evaluated the comprehensiveness aspect of the content validity. Of the 14 content validity studies involving experts, three studies [54, 103, 117] evaluated comprehensiveness with doubtful quality for two MA-PROMs [54, 117] and inadequate quality for one [103]. Of all studies involving experts, evaluated relevance, only two had adequate quality [89, 123].

3.1.2 Measurement Properties Other Than Content Validity

All 84 included studies evaluated at least one measurement property. The methodological quality ratings for each study of measurement properties for a MA-PROM and the rating for the overall result per MA-PROM are available in Supplementary Data – Table S2. Internal consistency (78 studies) was the most frequently evaluated measurement property. A total of 75 studies were found on construct validity (54 studies on convergent validity and 38 studies on known-group validity [KGV]). Structural validity and reliability were evaluated in 64 and 37 studies, respectively. Only three studies [65, 87, 103] evaluated the structural validity based on item response theory (IRT); two studies [65, 103] using a 2-parameter logistic model, and one study[87] using Rasch model. The remaining studies employed classical test theory (CTT). Five studies [81, 87, 88, 102, 108] on cross-cultural validity, and three studies [49, 77, 96] on responsiveness were found. No included studies evaluated measurement error or criterion validity. The methodological quality was evaluated for each measurement property across studies (Table 4). The quality of structural validity was rated as ‘very good’ in only 35% of studies (23/64). Nearly half of studies (52%, 41/78) on internal consistency had a ‘very good’ quality rating. About 62% of the studies (23/37) on reliability scored either a ‘doubtful’ or ‘inadequate’ quality rating. All but one study scored ‘doubtful’ for cross-cultural validity (5/5). One study reporting on the evaluation of construct validity using KGV had a very good rating [76], the quality of all other studies evaluating KGV was doubtful. All studies reporting on responsiveness (3/3) were rated ‘doubtful’. The highest number of measurement properties, other than content validity, evaluated in a single study was five out eight (Table 4) [81, 102].

3.2 Evidence Synthesis per PROM

Medication adherence patient-reported outcome measures were classified into three groups based on whether the items gathered information on the extent of and/or the reasons for medication non-adherence (Table 5). They were also grouped with regard to the quality of the overall evidence for each measurement property [29, 31].

Eight MA-PROMs were classified in COSMIN recommendation category ‘A’; four in each of Group-2 [74, 97, 102, 122] and Group-3 [45, 65, 67, 81]. These MA-PROMs had sufficient results for both content validity (with very low quality of evidence) and internal consistency (with moderate-to high-quality evidence). The four MA-PROMs in Group-3 with category ‘A’ were prioritised for MA-PROM selection as they are more comprehensive. Of these MA-PROMs, Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) [81] or ARMS-7 [67] have high-quality evidence for sufficient results on a higher number of measurement properties, including structural validity, internal consistency, reliability (moderate-quality for ARMS), and construct validity. In addition, the original ARMS had sufficient result on measurement invariance with low-quality evidence. Consequently, the most suitable MA-PROMs for people with CVD are ARMS or ARMS-7.

Four MA-PROMs had high quality evidence of insufficient results for at least one measurement property and were classified in COSMIN recommendation category ‘C’. Two MA-PROMs in Group-2 (Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension [MUAH], and MUAH-16) and two in Group-3 (Hill–Bone Compliance Medication Scale [HBMS] and the five-item Medication Adherence Report Scale [MARS-5]). There was high-quality evidence on insufficient structural validity for MUAH, insufficient internal consistency for MAUH-16 and MARS-5, and insufficient construct validity for HBMS.

Most of the MA-PROMs had very low-quality evidence for content validity. Only two MA-PROMs [54, 117] had moderate-quality evidence for sufficient results on overall content validity based on the evidence from more than one content validity study with doubtful methodological quality. There was no high-quality evidence on insufficient content validity for any of the MA-PROMs; consequently, the other measurement properties for each MA-PROM were further evaluated.

The most commonly used MA-PROM, the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), exhibited high-quality evidence for sufficient construct validity, and low-quality evidence for sufficient reliability (downgraded due to risk of bias and inconsistent results). However, the overall rating of MMAS-8 on internal consistency cannot be determined because the results per study on structural validity of MMAS-8 were inconsistent (only 57% of studies had the same factor structure with inconsistent results (should be 75% or greater).

The 4-item Morisky Green Levine Scale (MGLS) from Group-2 was the second most frequently evaluated MA-PROM, and there was low-quality evidence for sufficient structure validity and responsiveness, and very low-quality evidence for sufficient reliability, but it exhibited insufficient internal consistency with low-quality evidence, and insufficient construct validity with moderate-quality evidence (downgraded due to inconsistent results).

4 Discussion

This systematic review used the COSMIN guidelines to evaluate measurement properties [29, 33, 34] and feasibility [29, 132] to select the most suitable MA-PROM for people with CVD. Results on the evaluation of medication adherence using the selected PROM(s) should be trustworthy for use in patients with CVDs. A suitable PROM requires at least both sufficient content validity with any level of evidence and sufficient internal consistency with at least low-quality evidence [132] according to COSMIN guidelines [29, 31]. Eight of the 40 identified MA-PROMs were found to have sufficient content validity (all with very low quality evidence), and sufficient internal consistency with moderate to high quality evidence based [29, 31, 45, 46, 65, 74, 81, 97, 102, 122]. Of these eight MA-PROMs, only ARMS and ARMS-7 are comprehensive and have moderate to high quality evidence for three other measurement properties, including structural validity, reliability, and construct validity.

Despite favourable findings on the quality of measurement properties, previous systematic reviews [133, 134] did not recommend ARMS and ARMS-7 as suitable MA-PROMs. The primary reason for this difference is that both reviews [133, 134] did not follow the COSMIN category of recommendations, which requires sufficient content validity with any level of evidence, and sufficient internal consistency with at least low-quality evidence as a prerequisite for category “A”. Instead, the previous reviews [133, 134] recommended PROMs with a higher number of measurement properties with at least moderate-quality evidence for sufficient results. One review [133] found that the ARMS exhibited strong evidence of sufficient content validity and internal consistency which, according to the COSMIN guideline, should have been classified as recommendation category “A”. On the other hand in the review [133], MMAS-8 showed insufficient internal consistency with strong evidence and no content validity rating (COSMIN recommendation category “C”) and was recommended as a suitable MA-PROM for people at risk of metabolic disorders [133]. The other review [134] reported that both ARMS and ARMS-7 have high-quality evidence for sufficient internal consistency and low-quality evidence for sufficient content validity (ARMS) and indeterminate content validity (ARMS-7) [134]. Consequently, according to the COSMIN category of recommendations [29, 31] the ARMS should have been recommended at least as a suitable MA-PROM by the authors [134]. Another issue in the previous reviews [29, 31, 133, 134] is that the summarised result with a level of evidence for content validity was not rated for some MA-PROMs. According to COSMIN criteria, content validity should be rated as either sufficient, insufficient, or inconsistent, but not indeterminate. The result of content validity should be rated at least with the reviewers’ rating of the PROM itself and grading the evidence with very-low quality when the development study is inadequate and there is no or inadequate content validity studies [34].

Content validity is the first and most important measurement property to be considered for the selection of a PROM because there should be evidence to confirm that the items of a PROM are relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible in relation to the construct (e.g., medication adherence) and target population (e.g., people with CVD) [34, 132]. The lack of high-quality evidence on content validity of PROMs to measure medication adherence for people with CVD is highlighted by this review. Most of the MA-PROMs had very low-quality evidence for content validity. For MA-PROMs that were developed without patient involvement, in both concept elicitation and cognitive interview, content validity should be evaluated for a use in patients with CVD. This is because content validity studies can provide stronger evidence than the PROM development study. Poorly developed PROM (inadequate quality) can have high quality evidence on content validity provided that there is at least one content validity study with very good or adequate quality [34]. Additional content validity studies are also required for all MA-PROMs included in this review to provide high quality evidence for sufficient relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility. The content validity studies should include both patients and experts in the field [34].

Apart from content validity, the most frequently evaluated measurement properties were construct validity, internal consistency and structural validity. Consistent findings of internal consistency, construct validity, and structural validity in a previous systematic review of MA-PROMs for patients at risk of metabolic syndrome were found [133], while construct validity and internal consistency in another review of MA-PROMs for all chronic diseases [134] were found as the most frequently evaluated measurement properties.

No studies in the current review evaluated criterion validity, which is consistent with a previous review [134]. Criterion validity was reported in the other review for studies that reported correlations, area under the curve, sensitivity, or specificity regardless of the type of outcome comparator used [133]. However, the COSMIN guidelines [31, 33] suggested that there is no gold standard measure for PROMs, unless the original PROM is used as a comparator for the validation of the modified version PROM. In such a case, the original PROM becomes the default gold standard measure [31]. None of the studies evaluating a modified version of a MA-PROM used original PROM as a comparator for validation purposes in the current review.

Structural validity is the second measurement property to be considered for the selection of PROM and it is also a prerequisite for internal consistency [132]. Few studies had very good quality on structural validity using CFA or IRT/Rasch model. According to COSMIN guidelines, the use of Cronbach’s alpha for the total score of multidimensional scale cannot be interpreted unless there is evidence for unidimensionality from a high-order or bi-factor CFA [29].

Most reliability studies had doubtful or inadequate methodological quality. As a result of an inappropriate time interval for test-retest, different test conditions, or choice of statistical methods. A 2-week time interval is often deemed appropriate for the evaluation test-retest reliability [135]. The test and the retest conditions, such as mode of administration, and settings, should be similar. For PROMs with continuous scores, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) should be calculated [135] using a two-way random effects model [136]. The methodological quality for all studies on KGV (except for one study) was doubtful, mainly because the important characteristics, such as age, gender, etc., were not reported for the two groups (e.g., between groups with controlled and uncontrolled blood pressure) when comparing the score of a PROM [31]. Responsiveness can only be evaluated in studies that use a longitudinal study design to measure changes over time in medication adherence. Consequently, only three studies [49, 77, 96] evaluated responsiveness.

Four of the identified MA-PROMS (MUAH, MUAH-16, HBMS and MARS-5) cannot be recommended for use in patients with CVD as they were classified in COSMIN recommendation category ‘C’. Most of the identified MA-PROMs, including MMAS-8, were classified in the COSMIN recommendation category of ‘B’. These MA-PROMs could still potentially be recommended; however, further validation studies are required.

The MMAS-8 was the most frequently evaluated MA-PROM for patients with CVD. It has inconsistent structural validity and indeterminate internal consistency and was classified in the COSMIN recommendation category of ‘B’. Consequently, it requires further validation studies to provide evidence for sufficient structural validity and to obtain interpretable and sufficient internal consistency with at least low-quality evidence. Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 exhibited sufficient construct validity with high-quality evidence, and sufficient reliability with low-quality evidence. Using the 2010 COSMIN guidelines [137] and different target populations, a previous review-1 by Kim et al reported that MMAS-8 had strong evidence for sufficient structural validity, and insufficient internal consistency for people at risk for metabolic syndrome [133]. In the Kwan et al review-2 [134], MMAS-8 exhibited inconsistent structural validity, internal consistency and construct validity with high quality evidence for people with any medical condition. Another review-3 of reliability and validity of MMAS-8 in chronic diseases found that MMAS-8 had sufficient pooled results of internal consistency but the reliability (test-retest) and criterion validity were not sufficient in hypertensive patients [138]. A difference between the current review and the review-3 [138] may be attributable to the use of different guidelines for methodological quality assessment (COSMIN vs QUADAS-2).

The eight MA-PROMs in COSMIN category “A” should be used with caution considering different contexts such as the domains, phases of medication adherence to be measured or target language, and feasibility, including cost and time to complete the PROM. In terms of context, MA-PROMs that have items about extent of non-adherence, intentional and unintentional reasons for non-adherence, and measure both implementation and discontinuation phases are more comprehensive and can be prioritised to select the most suitable MA-PROM. Defined by Vrijens et al [139], that adherence to medication is the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed, further divided into three quantifiable phases: ‘Initiation’, ‘Implementation’ and ‘Discontinuation’, is reported in the current review. Most MA-PROMs had items that could evaluate the implementation of prescribed medications. Of the eight MA-PROMs in COSMIN recommendation category “A”, only Adherence Barriers Questionnaire (ABQ), ARMS and ARMS-7 measure both the implementation and discontinuation phases of medication adherence. Considering domains of medication adherence, ABQ has items that ask about reasons for non-adherence (intentional and unintentional), whereas ARMS and ARMS-7 are more comprehensive having items that capture information about the extent of (medication taking, and refills), unintentional and intentional non-adherence. Unlike ARMS, ARMS-7 does not seek information on the routine subdomain of unintentional non-adherence, and is missing some important items including skipping doses (extent of non-adherence), and being careless (remembering), changing dosing to suit needs (routine), forgetting to take medication due to frequent dosing (remembering), and not refilling medication due to high cost (access).

Feasibility aspects (clinical utility) should also be taken into consideration when selecting a PROM and may include any costs for using the PROM (i.e., copyright), time required to complete the PROM, length of the PROM, mode of administration, and response format [132]. Of the MA-PROMs categorised in COSMIN recommendation category ‘A’, only ABQ is licensed and subject to charge [95, 97]. Response format of the PROM should consider different factors including the intended target population; for example, the visual analogue scale (VAS) response format is not appropriate for patients with visual impairment [140]. Ceiling or floor effects could be avoided by using PROMs with a polytomous response format, such as a ≥4-item Likert scale [21]. The ARMS and ARMS-7 have a frequency response format with 4-point Likert scale, and free of charge for students and not-for-profit organisations.

4.1 Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

The current study has gone some way towards enhancing understanding of the quality and clinical usability of the available MA-PROMs for people with CVD. Cardiovascular medications are an important intervention for the prevention of CVD, control of symptoms, and reduction of complications and their associated hospital admission. Non-adherence could mask the benefits of treatment leading to misinformed decisions in clinical practice and research, necessitating the need to monitor medication adherence. Clinicians or researchers can use MA-PROMs to monitor medication adherence and assist in the identification of whether treatment failure is due to non-adherence or ineffective treatment and therefore facilitate informed treatment decisions [15]. Another use of MA-PROMs is to identify patients at risk for non-adherence, along with possible reasons for non-adherence, assisting patient-clinician interaction and shared decision making, to facilitate tailored care and ultimately improve CVD treatment outcomes [141, 142].

Before the integration of MA-PROMs into clinical practice and research, a number of factors need to be considered. MA-PROMs should be chosen on the basis of demonstrated feasibility, reliability and measurement accuracy rather than popularity. Clinicians and researchers should ensure items of the selected MA-PROM capture the important information relevant to the targeted CVD and medication adherence. Before using a PROM in clinical practice there should be evidence that a change in the PROM score is due to a 'true' change in the construct of interest rather than by chance. A measurement obtained using selected MA-PROM (adherent or non-adherent) should be meaningfully linked to one of the targeted clinical endpoints of CVD, such as blood pressure, cholesterol level, or symptom control. This information could be obtained using a known-group validity or discriminative validity [29, 31].

COSMIN guidelines are currently being used to evaluate the clinimetric properties of PROMs [143,144,145] and a recent review by Carrozzino et al has advocated the use of a clinimetric methodological approach to evaluate PROMs for clinical use [28]. Authors of future systematic reviews of PROMS for clinical use should consider whether to use COSMIN guidelines, clinimetric methodological approach or a combination of the two.

4.2 Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this review lie in the methods including the use of the latest 2018 COSMIN guidelines [29, 33, 34], following a prior published protocol [36], and using a published sensitive search terms for measurement properties [38]. Another strength of this review is that PROM development and content validity studies were evaluated because content validity is the first and most important measurement property for decision in the selection of suitable PROMs. In addition to measurement properties, the context and feasibility aspects of the MA-PROMs were evaluated to guide the selection of the most suitable MA-PROM for people with CVD.

The review has some potential limitations. The study findings should be interpreted with a degree of caution in terms of clinimetric properties. The measurement properties of MA-PROMs were evaluated based on COSMIN guidelines that are more focused on classical psychometric criteria than clinical criteria and may miss some clinimetric issues. Another limitation is that the review focuses on all types of CVD with more evidence being obtained for HTN than other CVD. Therefore, careful consideration should be taken when a MA-PROM suitable for all CVD is preferred and we recommend selecting a generic PROM with COSMIN recommendation category ‘A’. Non-English articles were not included which may be a source of language bias and results of this review are not generalisable to medical conditions other than CVD.

5 Conclusion

Forty MA-PROMs were identified in this systematic review. Of these, eight were classified using the COSMIN criteria as the most suitable for evaluating medication adherence in people with CVD and four as not recommended. Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale and ARMS-7 were identified as the most suitable MA-PROMs as they had the highest quality evidence for good measurement properties and were the most comprehensive. They measure both implementation and discontinuation phases of medication adherence, have a 4-point Likert scale frequency response format, and are free of charge for use by students and non-profit organisations. Most MA-PROMs require further studies for people with CVD to obtain higher quality evidence, particularly for content validity.

References

Clark H. NCDs: a challenge to sustainable human development. Lancet. 2013;381(9866):510–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60058-6.

Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61682-2.

Bowry AD, Lewey J, Dugani SB, Choudhry NK. The burden of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries: epidemiology and management. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1151–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.028.

World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2022 Sept 1]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44203/9789241563871_eng.pdf.

World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: guidelines for assessment and management of total cardiovascular risk. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007 [cited 2022 Sept 1]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43685.

World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003 [cited 2022 Sept 1]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42682.

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3.

Poluzzi E, Piccinni C, Carta P, Puccini A, Lanzoni M, Motola D, et al. Cardiovascular events in statin recipients: impact of adherence to treatment in a 3-year record linkage study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):407–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-010-0958-3.

Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–35. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.108.768986.

Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–14. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575.

Roebuck MC, Liberman JN, Gemmill-Toyama M, Brennan TA. Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(1):91–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1087.

Kini V, Ho PM. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence: A Review. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2461–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.19271.

Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000011.pub4.

Lowry KP, Dudley TK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence to antihypertensive medication. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(7–8):1198–203. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1e594.

Stirratt MJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Crane HM, Simoni JM, Czajkowski S, Hilliard ME, et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behaviour: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(4):470–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0315-2.

Williams AB, Amico KR, Bova C, Womack JA. A proposal for quality standards for measuring medication adherence in research. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):284–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0172-7.

Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication adherence measures: an overview. Biomed Res Int. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/217047.

Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–8. https://doi.org/10.4137/hsi.S11093.

Rothrock NE, Kaiser KA, Cella D. Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(5):737–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.195.

Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):115–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6.

US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-79.

Johnston BC, Patrick DL, Devji T, Maxwell LJ, Bingham III CO, Beaton DE, et al. Patient‐reported outcomes. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, 2019; p. 479–92. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119536604.ch18

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to Medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra050100.

Garfield S, Clifford S, Eliasson L, Barber N, Willson A. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-149.

Nguyen TM, La Caze A, Cottrell N. What are validated self-report adherence scales really measuring?: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(3):427–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12194.

Rolley JX, Davidson PM, Dennison CR, Ong A, Everett B, Salamonson Y. Medication adherence self-report instruments: implications for practice and research. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23(6):497–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jcn.0000338931.96834.16.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006.

Carrozzino D, Patierno C, Guidi J, Montiel CB, Cao J, Charlson ME, et al. Clinimetric criteria for patient-reported outcome measures. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(4):222–32. https://doi.org/10.1159/000516599.

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3.

Smart A. A multi-dimensional model of clinical utility. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(5):377–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl034.

Mokkink LB, Prinsen C, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC, et al. COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)-user manual 2018. https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/guideline-conducting-systematic-review-outcome-measures/.

Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d’Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(7):745–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013.

Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, et al. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1171–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4.

Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Tegegn HG, Tursan D’Espaignet E, Wark S, Spark MJ. Self-reported medication adherence tools in cardiovascular disease: protocol for a systematic review of measurement properties. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(7):1546–56. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-d-19-00117.

Aromataris E, Riitano D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000446779.99522.f6.

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. Development of a Methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1115–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9528-5.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Johnson MJ. The Medication Adherence Model: a guide for assessing medication taking. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002;16(3):179–92. https://doi.org/10.1891/rtnp.16.3.179.53008.

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):651–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1.

Alhazzani H, AlAmmari G, AlRajhi N, Sales I, Jamal A, Almigbal TH, et al. Validation of an Arabic version of the self-efficacy for appropriate medication use scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211983.

Arnet I, Metaxas C, Walter PN, Morisky DE, Hersberger KE. The 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale translated in German and validated against objective and subjective polypharmacy adherence measures in cardiovascular patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(2):271–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12303.

Aşılar RH, Gözüm S, Çapık C, Morisky DE. Reliability and validity of the Turkish form of the eight-item morisky medication adherence scale in hypertensive patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2014;14(8):692–700. https://doi.org/10.5152/akd.2014.4982.

Athavale AS, Bentley JP, Banahan BF, McCaffrey DJ, Pace PF, Vorhies DW. Development of the medication adherence estimation and differentiation scale (MEDS). Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):577–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1512478.

Barati M, Taheri-Kharameh Z, Bandehelahi K, Yeh VM, Kripalani S. Validation of the Short Form of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS-SF) in Iranian Elders with Chronic Disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2018/37584.12305.

Ben AJ, Neumann CR, Mengue SS. The Brief Medication Questionnaire and Morisky-Green test to evaluate medication adherence. Rev Saude Publica. 2012;46(2):279–89. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102012005000013.

Beyhaghi H, Reeve BB, Rodgers JE, Stearns SC. Psychometric properties of the four-item Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale among atherosclerosis isk in communities (ARIC) study participants. Value Health. 2016;19(8):996–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.07.001.

Blalock DV, Zullig LL, Bosworth HB, Taylor SS, Voils CI. Self-reported medication nonadherence predicts cholesterol levels over time. J Psychosom Res. 2019;118:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.01.010.

Bou Serhal R, Salameh P, Wakim N, Issa C, Kassem B, Abou Jaoude L, et al. A new Lebanese medication adherence scale: validation in Lebanese hypertensive adults. Int J Hypertens. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3934296.

Cabral AC, Castel-Branco M, Caramona M, Fernandez-Llimos F, Figueiredo IV. Developing an adherence in hypertension questionnaire short version: MUAH-16. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(1):118–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13137.

Cabral AC, Moura-Ramos M, Castel-Branco M, Fernandez-Llimos F, Figueiredo IV. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a European Portuguese version of the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale. Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37(4):297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2017.09.017.

Chan AHY, Horne R, Hankins M, Chisari C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: a measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(7):1281–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14193.

Chen P-F, Chang EH, Unni EJ, Hung M. Development of the chinese version of medication adherence reasons scale (ChMAR-scale). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155578.

Chen YJ, Chang J, Yang SY. Psychometric evaluation of Chinese Version of Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) and Blood-Pressure Control Among Elderly with Hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:213–20. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S236268.

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37(9):846–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199909000-00002.

Cook CL, Wade WE, Martin BC, Perri M III. Concordance among three self-reported measures of medication adherence and pharmacy refill records. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2005;45(2):151–9. https://doi.org/10.1331/1544345053623573.

Cornelius T, Voils CI, Umland RC, Kronish IM. Validity Of The Self-Reported Domains Of Subjective Extent Of Nonadherence (DOSE-Nonadherence) Scale In Comparison With Electronically Monitored Adherence To Cardiovascular Medications. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1677–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S225460.

de Oliveira-Filho AD, Morisky DE, Neves SJ, Costa FA, Lyra de Jr. DP. The 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale: validation of a Brazilian-Portuguese version in hypertensive adults. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(3):554–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.10.006.

de Santa Helena ET, Battistella Nemes MI, Eluf-Neto J. Development and validation of a multidimensional questionnaire assessing non-adherence to medicines. Rev Saude Publ. 2008;42(4):764–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102008000400025.

Dehghan M, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Iranmanesh S. Translation and validation of the Persian version of the treatment adherence questionnaire for patients with hypertension. ARYA Atheroscler. 2016;12(2):76–86.

Dehghan M, Nayeri ND, Karimzadeh P, Iranmanesh S. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Morisky medication adherence scale-8. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;9(9):1–10. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMMR/2015/17345.

Dong XF, Liu YJ, Wang AX, Lv PH. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the self-efficacy for appropriate medication use scale in patients with stroke. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:321–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S101844.

Esquivel Garzón N, Díaz Heredia LP. Validity and reliability of the treatment adherence questionnaire for patients with hypertension. Invest Educ Enferm. 2019. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v37n3e09.

Fernandez S, Chaplin W, Schoenthaler AM, Ogedegbe G. Revision and Validation of the medication adherence self-efficacy scale (MASES) in hypertensive African Americans. J Behav Med. 2008;31(6):453–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9170-7.

Gallagher BD, Muntner P, Moise N, Lin JJ, Kronish IM. Are two commonly used self-report questionnaires useful for identifying antihypertensive medication nonadherence? J Hypertens. 2015;33(5):1108–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000000503.

Gökdoğan F, Kes D. Validity and reliability of the Turkish Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(5): e12566. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12566.

Gozum S, Hacihasanoglu R. Reliability and validity of the Turkish adaptation of medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8(2):129–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.10.006.

Grover A, Oberoi M, Rehan HS, Gupta LK, Yadav M. Self-reported Morisky Eight-item Medication Adherence Scale for Statins Concords with the Pill Count Method and Correlates with Serum Lipid Profile Parameters and Serum HMGCoA Reductase Levels. Cureus. 2020;12(1): e6542. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6542.

Hacihasanoglu R, Gozum S, Capik C. Validity of the Turkish version of the medication adherence self-efficacy scale-short form in hypertensive patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2012;12(3):241–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/akd.2012.068.

He W, Bonner A, Anderson D. Patient reported adherence to hypertension treatment: a revalidation study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15(2):150–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515115603902.

Jankowska-Polanska B, Uchmanowicz I, Chudiak A, Dudek K, Morisky DE, Szymanska-Chabowska A. Psychometric properties of the polish version of the eight-item morisky medication adherence scale in hypertensive adults. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1759–66. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S101904.

Johnson MJ. The medication-taking questionnaire for measuring patterned behaviour adherence. Commun Nurs Res. 2002;35:65–70.

Johnson MJ, Rogers S. Development of the purposeful action medication-taking questionnaire. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(3):335–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945905284726.

Karademir M, Koseoglu IH, Vatansever K, Van Den Akker M. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Hill-Bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale for use in primary health care settings. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15(4):207–11. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814780903452150.

Kim JH, Lee WY, Hong YP, Ryu WS, Lee KJ, Lee WS, et al. Psychometric properties of a short self-reported measure of medication adherence among patients with hypertension treated in a busy clinical setting in Korea. J Epidemiol. 2014;24(2):132–40. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.je20130064.

Kim MT, Hill MN, Bone LR, Levine DM. Development and testing of the Hill-Bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000;15(3):90–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7117.2000.tb00211.x.

Kjeldsen LJ, Bjerrum L, Herborg H, Knudsen P, Rossing C, Søndergaard B. Development of new concepts of non-adherence measurements among users of antihypertensives medicines. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(3):565–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9509-y.

Korb-Savoldelli V, Gillaizeau F, Pouchot J, Lenain E, Postel-Vinay N, Plouin PF, et al. Validation of a French version of the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale in hypertensive adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(7):429–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00634.x.

Koschack J, Marx G, Schnakenberg J, Kochen MM, Himmel W. Comparison of two self-rating instruments for medication adherence assessment in hypertension revealed insufficient psychometric properties. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(3):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.011.

Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Development and Evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009;12(1):118–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00400.x.

Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re RN, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(1):59–66.

Krousel-Wood M, Muntner P, Jannu A, Desalvo K, Re RN. Reliability of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330(3):128–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200509000-00006.

Ladova K, Matoulkova P, Zadak Z, Macek K, Vyroubal P, Vlcek J, et al. Self-reported adherence by MARS-CZ reflects LDL cholesterol goal achievement among statin users: validation study in the Czech Republic. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(5):671–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12201.

Lambert EV, Steyn K, Stender S, Everage N, Fourie JM, Hill M. Cross-cultural validation of the hill-bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale in a South African, primary healthcare setting. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):286–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(02)02817-0.

Lehane E, McCarthy G, Collender V, Deasy A, O’Sullivan K. The reasoning and regulating medication adherence instrument for patients with coronary artery disease: development and psychometric evaluation. J Nurs Meas. 2013;21(1):64–79. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.21.1.64.

Lin C-Y, Ou H-T, Nikoobakht M, Brostrom A, Arestedt K, Pakpour AH. Validation of the 5-item medication adherence report scale in older stroke patients in Iran. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(6):536–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000488.

Lomper K, Chabowski M, Chudiak A, Białoszewski A, Dudek K, Jankowska-Polańska B. Psychometric evaluation of the Polish version of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) in adults with hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2661–70. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S185305.

Ma C, Chen S, You L, Luo Z, Xing C. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Treatment Adherence Questionnaire for Patients with Hypertension. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(6):1402–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05835.x.

Mahler C, Hermann K, Horne R, Ludt S, Haefeli WE, Szecsenyi J, et al. Assessing reported adherence to pharmacological treatment recommendations. Translation and evaluation of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(3):574–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01169.x.

Matta SR, Azeredo TB, Luiza VL. Internal consistency and interrater reliability of the Brazilian version of Martín-Bayarre-Grau (MBG) adherence scale. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2016;52(4):795–800. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-82502016000400025.

Matza LS, Park J, Coyne KS, Skinner EP, Malley KG, Wolever RQ. Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(10):1621–30. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M174.

Matza LS, Yu-Isenberg KS, Coyne KS, Park J, Wakefield J, Skinner EP, et al. Further testing of the reliability and validity of the ASK-20 adherence barrier questionnaire in a medical center outpatient population. J Curr Med Res. 2008;24(11):3197–206. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802463642.

Moharamzad Y, Saadat H, Nakhjavan Shahraki B, Rai A, Saadat Z, Aerab-Sheibani H, et al. Validation of the Persian Version of the 8-Item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) in Iranian Hypertensive Patients. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(4):173–83. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p173.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a Medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(5):348–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x.

Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007.

Muller S, Kohlmann T, Wilke T. Validation of the Adherence Barriers Questionnaire—an instrument for identifying potential risk factors associated with medication-related non-adherence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0809-0.

Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME. Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(6):520–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00053-2.

Okello S, Nasasira B, Muiru AN, Muyingo A. Validity and reliability of a self-reported measure of antihypertensive medication adherence in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7): e0158499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158499.

Pedrosa RB, Rodrigues RC, Oliveira HC, Alexandre NM. Construct validity of the Brazilian version of the self-efficacy for appropriate medication adherence scale. J Nurs Meas. 2016;24(1):E18-31. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.24.1.E18.

Prado JC Jr, Kupek E, Mion D Jr. Validity of four indirect methods to measure adherence in primary care hypertensives. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):579–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1002196.

Risser J, Jacobson TA, Kripalani S. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) in low-literacy patients with chronic disease. J Nurs Meas. 2007;15(3):203–19. https://doi.org/10.1891/106137407783095757.

Rodrigues MTP, Moreira TMM, Andrade DFd. Elaboration and validation of instrument to assess adherence to hypertension treatment. Rev Saude Publ. 2014;48(2):232–40. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-8910.2014048005044.

Saffari M, Zeidi IM, Fridlund B, Chen H, Pakpour AH. A Persian Adaptation of Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (MASES) in hypertensive patients: psychometric properties and factor structure. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2015;22(3):247–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-015-0101-8.

Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hay AD, Montgomery A, Peters TJ. Adherence to antihypertensive medication assessed by self-report was associated with electronic monitoring compliance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(6):650–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.013.

Shalansky SJ, Levy AR, Ignaszewski AP. Self-reported Morisky score for identifying nonadherence with cardiovascular medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(9):1363–8. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1E071.

Shilbayeh SAR, Almutairi WA, Alyahya SA, Alshammari NH, Shaheen E, Adam A. Validation of knowledge and adherence assessment tools among patients on warfarin therapy in a Saudi hospital anticoagulant clinic. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(1):56–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0569-5.

Shima R, Farizah H, Majid HA. The 11-item Medication Adherence Reasons Scale: reliability and factorial validity among patients with hypertension in Malaysian primary healthcare settings. Singap Med J. 2015;56(8):460–7. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2015069.

Shin DS, Kim CJ. Psychometric evaluation of a Korean version of the 8-item Medication Adherence Scale in rural older adults with hypertension. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21(6):336–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12070.

Song Y, Han HR, Song HJ, Nam S, Nguyen T, Kim MT. Psychometric evaluation of hill-bone medication adherence subscale. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2011;5(3):183–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2011.09.007.

Strelec MAAM, Pierin AM, Mion D Jr. The influence of patient’s consciousness regarding high blood pressure and patient’s attitude in face of disease controlling medicine intake. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003;81(4):349–54. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0066-782x2003001200002.

Surekha A, Fathima FN, Agrawal T, Misquith D. Psychometric properties of morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS) in known diabetic and hypertensive patients in a rural population of Kolar District, Karnataka. Indian J Publ Health Res Dev. 2016;7(2):250–6. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2016.00102.9.

Suwannapong K, Thanasilp S, Chaiyawat W. The development of medication adherence scale for persons with coronary artery disease (MAS-CAD): a nursing perspective. Walailak J Sci Technol. 2019;16(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.48048/wjst.2019.4046.

Svarstad BL, Chewning BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The Brief Medication Questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37(2):113–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00107-4.

Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polanska B, Chudiak A, Szymanska-Chabowska A, Mazur G. Psychometric evaluation of the Polish adaptation of the Hill-Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0270-y.

Unni EJ, Farris KB. Development of a new scale to measure self-reported medication nonadherence. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2009;11(3):e133–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.06.005.

Unni EJ, Olson JL, Farris KB. Revision and validation of medication adherence reasons scale (MAR-scale). Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(2):211–21. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2013.851075.

van de Steeg N, Sielk M, Pentzek M, Bakx C, Altiner A. Drug-adherence questionnaires not valid for patients taking blood-pressure-lowering drugs in a primary health care setting. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):468–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01038.x.

Voils CI, Maciejewski ML, Hoyle RH, Reeve BB, Gallagher P, Bryson CL, et al. Initial validation of a self-report measure of the extent of and reasons for medication nonadherence. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1013–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e121.

Weinman J, Graham S, Canfield M, Kleinstauber M, Perera AI, Dalbeth N, et al. The Intentional Non-Adherence Scale (INAS): Initial development and validation. J Psychosom Res. 2018;115:110–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.010.

Wetzels G, Nelemans P, van Wijk B, Broers N, Schouten J, Prins M. Determinants of poor adherence in hypertensive patients: development and validation of the “Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH)-questionnaire.” Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):151–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.010.

Wu JR, Chung M, Lennie TA, Hall LA, Moser DK. Testing the psychometric properties of the Medication Adherence Scale in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37(5):334–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.10.001.

Yan J, You LM, Yang Q, Liu B, Jin S, Zhou J, et al. Translation and validation of a Chinese version of the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale in myocardial infarction patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(4):311–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12125.

Yu M, Wang L, Guan L, Qian M, Lv J, Teo JYC, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Medication Adherence Scale in older Chinese patients with coronary heart disease. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(6):1482–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.008.

Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, Battegay E. Patients’ self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(11):2037–43. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.31.2037.

Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440290001502.

Hahn SR, Park J, Skinner EP, Yu-Isenberg KS, Weaver MB, Crawford B, et al. Development of the ASK-20 Adherence Barrier Survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(7):2127–38. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802174769.

Johnson MJ, Williams M, Marshall ES. Adherent and nonadherent medication-taking in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin Nurs Res. 1999;8(4):318–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/10547739922158331.

Johnson MJM. The development and testing of three medication-taking questionnaires for the medication adherence model constructs in hypertensive patients. The University of Utah; 2001.

Ogedegbe G, Harrison M, Robbins L, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP. Barriers and facilitators of medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: a qualitative study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(1):3–12.

Alammari G, Alhazzani H, AlRajhi N, Sales I, Jamal A, Almigbal TH, et al. Validation of an Arabic Version of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS). Healthcare (Basel). 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111430.

Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, et al. How to Select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”—a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17(1):449. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2.

Kim CJ, Schlenk EA, Ahn JA, Kim M, Park E, Park J. Evaluation of the measurement properties of self-reported medication adherence instruments among people at risk for metabolic syndrome: a Systematic review. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(5):618–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721716655400.