Abstract

Background and Objectives

Knee osteoarthritis pain is a chronic form of pain for which conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may provide insufficient analgesia. Twice-daily tramadol hydrochloride (65% sustained-release/35% immediate-release) bilayer tablets are a novel formulation of tramadol developed for managing chronic pain. The objectives of this study were to examine the effectiveness and safety of this formulation in patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis pain.

Methods

This was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, treatment-withdrawal study. Patients with a reduction in Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain of ≥2 points during a 1–3-week, open-label, tramadol dose-escalation period (100–300 mg/day) were randomized to continue tramadol or switched to placebo for 4 weeks (double-blind period). Patients with inadequate efficacy (increase in NRS ≥2 points/patient request) were withdrawn. Outcomes included the time to inadequate analgesic efficacy from randomization (primary endpoint), the cumulative retention rate, and safety.

Results

Overall, 249 and 160 patients entered the dose-escalation and double-blind periods, respectively (tramadol 79; placebo 81). Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed superiority of tramadol (log-rank p = 0.042), and a hazard ratio of 0.50 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.25–0.99). Documentation of an inadequate analgesic effect was less frequent in the tramadol group (15.4%, 95% CI 8.2–25.3% vs. 30.9%, 95% CI 21.1–42.1%). The cumulative retention rate was greater in the tramadol group (83.7% vs. 69.0%). Adverse events occurred in 80.6% (200/248) of patients in the open-label period, and in 38.5% (30/78) and 13.6% (11/81) of patients in the tramadol and placebo groups, respectively, in the double-blind period. Opioid-associated adverse events, such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, somnolence, and dizziness, were the most frequent events.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the analgesic efficacy and safety of sustained-release tramadol tablets with an immediate-release component for chronic knee osteoarthritis pain.

Trial registration

JapicCTI-132103 (Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center; registration date February 25, 2015)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This study investigated the efficacy and safety of a twice-daily bilayer tablet formulation of tramadol hydrochloride (65% sustained-release/35% immediate-release) versus placebo in patients with chronic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis. |

Tramadol was associated with prolonged adequacy of pain relief and higher cumulative retention rate than placebo. Adverse events included nausea, vomiting, constipation, somnolence, and dizziness, which are known to be related to opioids. |

The results demonstrate the analgesic efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sustained-release tramadol bilayer tablets with an immediate-release component for managing chronic knee osteoarthritis. |

1 Introduction

Osteoarthritis affects about 20% of adults, and its incidence is expected to increase due to aging of the population, dietary and lifestyle factors, and increasing rates of obesity [1,2,3]. Joint pain, tenderness, and joint stiffness are among the major clinical features that significantly affect the patient’s ability to perform daily life activities [4]. Patients with chronic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis are also at increased risk of early mortality compared with the general population [5].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely considered as the first-line pharmacologic therapy for osteoarthritis pain [6,7,8,9]. However, they are not suitable for all patients due to the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular side effects, and renal side effects [6, 7, 10, 11].

Although osteoarthritis pain is conventionally regarded as nociceptive pain, recent evidence suggests that it also has a significant neuropathic component [3, 12]. NSAIDs and other first-line analgesics may reduce nociceptive pain but often show limited effects on chronic neuropathic pain. Therefore, many patients may require alternatives, such as opioids or serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Tramadol has been incorporated into clinical recommendations, with “weak” or “conditional” recommendations for managing pain associated with knee osteoarthritis [6, 7], reflecting limited clinical studies and potential concern regarding its tolerability or dependency. Tramadol is a μ-opioid receptor agonist that also inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. It is useful for treating pain that is difficult to treat with non-opioid analgesics by targeting neuropathic and nociceptive pain [12, 13].

A variety of formulations of tramadol are available, including immediate-release formulations, administered up to four times per day, and extended-release formulations, administered once- or twice-daily. Clinical trials have demonstrated advantages of extended-release formulations in terms of maintaining pain relief and adherence [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], while avoiding pronounced peaks/troughs in circulating tramadol concentrations that may interfere with its analgesic effects or contribute to adverse events (AEs) [23, 24]. However, patients taking once-daily sustained/extended-release formulations may experience pain aggravation if the circulating tramadol concentration drops below the therapeutic level shortly before the next dose, or if other factors (e.g., missed dose) result in altered pharmacokinetics [25]. Several formulations of tramadol have been developed that combine extended-release and immediate-release components as biphasic tablets or multicomponent capsules [26, 27]. It is anticipated that some patients will benefit from twice-daily administration of such formulations, which maintain the circulating levels of tramadol without significant fluctuations, and thus provide adequate analgesia throughout the day.

Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) developed a twice-daily, bilayer formulation of sustained-release tramadol with an immediate-release component (65% sustained-release/35% immediate-release) (Twotram® tablets) [28]. Following oral administration, the immediate-release component dissolves quickly to provide a rapid increase in the plasma concentrations of tramadol and its active metabolite (M1), as illustrated in a single-dose bioequivalence study (Fig. 1a; NZ-687-BE-1 bioequivalence study). The sustained-release component dissolves more slowly resulting in stable trough plasma concentrations, as illustrated in a multiple-dose pharmacokinetic study (Fig. 1b; NZ-687-I-J2 pharmacokinetic study) [28]. As part of its clinical development, this trial was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of twice-daily administration in patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis pain. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report describing a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, treatment-withdrawal clinical trial of a twice-daily, bilayer tramadol formulation in this setting.

Pharmacokinetics of sustained-release tramadol hydrochloride bilayer tablets with an immediate-release component [28]. a Plasma tramadol and M1 concentrations after a single dose of 50, 100, or 150 mg tramadol in healthy volunteers (NZ-687-BE-1 bioequivalence study). b Plasma tramadol and M1 concentrations in repeated-dose studies with 50 or 100 mg tablets in healthy volunteers (NZ-687-I-J2 pharmacokinetic study). Tramadol tablets were administered once-daily on Days 1 and 7 and twice-daily from Days 2 to 6. The trough concentrations are shown between 24 and 144 hours. Plasma concentrations are shown as the mean ± standard deviation

2 Patients and Methods

2.1 Ethics

This clinical study was performed between May 2013 and December 2014. The study conformed with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Standards for the Implementation of Clinical Trials (Good Clinical Practice), and the study protocol, which was approved by the institutional review boards at the 24 participating medical institutions in Japan. All patients provided written informed consent. This study was registered on the Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center Clinical Trials Information registry (JapicCTI-132103).

2.2 Patients

Patients who met the 1986 American Rheumatism Association criteria for the classification of osteoarthritis with some modifications [29] were eligible if osteophyte, osteosclerosis, or joint space narrowing was observed on radiography with knee osteoarthritis-induced chronic pain symptoms persisting for ≥3 months. Other eligibility criteria were continuous administration of NSAIDs at an approved dosage for ≥2 weeks prior to the trial or patients unable to take NSAIDs due to contraindications, and a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) value for maximum pain of ≥4 for the evaluated knee up to 24 h prior to screening. The exclusion criteria and prohibited therapies are described in Online Resource 1. NSAIDs (for osteoarthritis), aspirin (as antithrombotic medication), and prochlorperazine (as an antiemetic) could be continued at the same dose in patients using these drugs prior to enrolment. Rescue analgesics were not permitted. Antiemetics and laxatives were not permitted until after a patient first experienced nausea, vomiting, or constipation.

2.3 Study Design

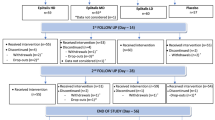

This multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind parallel-group, treatment-withdrawal study comprised the following periods: pretreatment screening/observation period (1 week), open-label dose-escalation period (1–3 weeks), fixed-dose period (1 week), double-blind period (4 weeks), and a post-treatment observation period (2 weeks) (Fig. 2) with a total treatment period of up to 8 weeks (up to nine visits).

Study design. aThe tramadol dose was escalated if the analgesic effect was inadequate (the Numeric Rating Scale [NRS] averaged over the 3 days preceding the visit did not improve by ≥2 points). bPatients were withdrawn from the study if the NRS values averaged over the 3 days preceding the visit did not improve by ≥2 points or if the medication adherence was <70% during the dose-escalation period. cPatients were withdrawn from the study if the NRS averaged over the 3 days preceding the visit did not improve by ≥2 points relative to Visit 1, the difference between the minimum and maximum values over the 3 days preceding Visit 5 was ≥2 points, or if medication adherence was <70% during the fixed-dose period. dPatients eligible for the open-label fixed-dose period skipped the intervening period

All patients who entered the open-label dose-escalation period started tramadol at a dose of 100 mg/day (1 × 50-mg tablet twice-daily) at Visit 1.

The patients recorded their NRS in diaries every day. The values recorded over the 3 days preceding each visit (except screening, which was assessed over 24 h prior to the visit) were arithmetically averaged and rounded to the nearest integer. The averaged values, and the minimum or maximum values, were used to assess the analgesic efficacy in each patient, including satisfaction of the eligibility criteria for each study period. Averaged values were used for data analyses.

Patients who satisfied both of the following criteria at Visit 2 or 3 in the dose-escalation period were eligible for transition to the open-label fixed-dose period: (a) improvement by ≥2 points in the NRS value preceding the visit and (b) a compliance rate of ≥70% during the dose-escalation period. If criterion (a) was not met at Visit 2 or 3, the tramadol dose was escalated to 200 mg/day (2× 50-mg tablets twice-daily) at Visit 2 and to 300 mg/day (3× 50-mg tablets twice-daily) at Visit 3. Patients who did not meet criterion (b) at either visit were withdrawn from the study. Patients who did not meet both criteria at Visit 4 were withdrawn from the study.

In the 1-week open-label fixed-dose period, patients continued tramadol at the dose reached in the dose-escalation period. Patients who satisfied the following criteria were eligible for randomization in the double-blind period: (a) improvement in the NRS value of ≥2 points between Visit 1 (baseline/Week 0) and Visit 5; (b) difference between the minimum and maximum NRS value of ≤2 points during the 3 days preceding Visit 5; and (c) compliance rate of ≥70% during the fixed-dose period.

Eligible patients were randomized (at Visit 5) to either tramadol or placebo at the dose (i.e., number of tablets) used during the open-label fixed-dose period (see Online Resource 1 for the randomization procedure). During this 4-week period, the allocated drug was discontinued if the analgesic effect became inadequate with an increase in the NRS value of ≥2 points averaged over the 3 days preceding Visits 6–9 relative to the value recorded at randomization (Visit 5/Week 0). To maintain blinding, the tramadol and placebo tablets were indistinguishable in appearance and packaging. Patients could withdraw in either period if they felt the analgesic effect was insufficient.

After the double-blind period or following discontinuation of the allocated drug, the patients entered a 2-week post-treatment observation period to evaluate the ongoing safety and tolerability.

2.4 Clinical Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the time (in days) to when the analgesic effect of the investigational drug became insufficient after entering the double-blind period. The secondary endpoints were the percentages of patients in whom the analgesic effects became insufficient in the double-blind period, and the changes in NRS values and Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (JKOM) [30, 31] scores in the open-label and double-blind periods. The NRS is an 11-point scale, where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst possible pain [32]. The JKOM is a 25-item questionnaire that yields an overall score and four domains: knee pain/stiffness (8 items), condition in daily life (10 items), general activities (5 items), and health conditions (2 items). Each item is scored on a range of 1–5, where 1 = best function and 5 = worst function; the scores for all 25 items are summed to yield the overall score with a possible range of 25–125 [30, 31]. The JKOM was completed at Visits 1, 5, and 9, or at the time of discontinuation.

Safety was assessed in terms of AEs, adverse reactions, abnormal laboratory test results, abnormal vital signs, and abnormal 12-lead electrocardiography documented between Visit 1 and the end of the post-treatment observation period. AEs were coded using the MedDRA/J (Version 17.1) by system organ class and preferred term.

Drug dependency was evaluated using a seven-item questionnaire at the end of the double-blind period (for randomized patients) or at the end of the open-label period (for patients who did not enter the double-blind period) (Online Resource 1).

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Efficacy data were analyzed using full analysis sets for the open (FAS-O) and double-blind (FAS-DB) periods. The FAS-O comprised all patients who started tramadol at Visit 1 in the open-label dose-escalation period for whom efficacy data were available. The FAS-DB comprised all patients who received at least one dose of the investigational drug in the double-blind period for whom data related to the primary endpoint were available. Safety analyses were performed using safety analysis sets for the open (SAF-O) and double-blind (SAF-DB) periods, which comprised patients who received at least one dose of the investigational drug in the corresponding period.

The log-rank test was used to compare the time from the start of the double-blind period until the analgesic effect of the study drug became insufficient (number of days; i.e., primary endpoint) to verify the superiority of tramadol over placebo. As a secondary analysis, the Cox regression model was used to determine point estimates of the hazard ratios (HRs) for tramadol versus placebo with two-sided 95% CIs for the primary endpoint. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to plot cumulative survival curves from the start of the double-blind period to the documentation of an inadequate analgesic effect, and the numbers at risk at each time-point were calculated. Safety outcomes were analyzed descriptively for the open-label and double-blind periods separately.

The sample size is described in Online Resource 1. The analyses were performed using SAS versions 9.2 and 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Patients

A total of 273 patients provided consent and started the pre-treatment observation period (Fig. 3). Of these, 249 entered the open-label dose-escalation period and started administration of tramadol at a dose of 100 mg/day. Eighty-nine patients discontinued in either the open-label dose-escalation or fixed-dose periods: 59 (23.7%) due to AEs, 25 (10.0%) due to inadequate efficacy, and five (2.0%) for other reasons. Thus, 160 patients entered the double-blind period and were randomized to continue tramadol (n = 79) or switch to placebo (n = 81), of whom 110 completed the double-blind period (tramadol n = 54; placebo n = 56). Twelve patients in the tramadol group and 25 in the placebo group discontinued due to inadequate efficacy. A further 13 patients discontinued in the tramadol group: 12 due to AEs and one for another reason. The SAF-O, FAS-O, SAF-DB, and FAS-DB comprised 248, 245, 159, and 159 patients, respectively. One patient was excluded from the SAF-O and FAS-O due to the loss of medical records. Three patients were excluded from the FAS-O due to missing efficacy data. One patient (tramadol group) was excluded from the SAF-DB and FAS-DB because the investigational drug was not administered in the double-blind period.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the FAS-DB are shown in Table 1. Two-thirds of the patients (67.9%) were female. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age and duration of pain symptoms were 67.3 ± 9.3 years and 46.3 ± 57.1 months, respectively. Most of the patients (95.6%) were previously treated with NSAIDs. The NRS value and JKOM overall score at baseline were 3.3 ± 1.5 and 43.4 ± 10.9 (mean ± SD), respectively. There were no appreciable differences in baseline characteristics between the tramadol and placebo groups that were considered likely to influence the interpretation of the efficacy or safety.

Among 248 patients in the SAF-O, compliance to the investigational drug was <70% in five (2.0%) patients during the 1-week fixed-dose period and in 35 (14.1%) patients during the dose-escalation period. At the end of the dose-escalation period (Visit 3), the tramadol doses were 100, 200, and 300 mg/day in 109, 94, and 46 patients, respectively. Among 181 patients who entered the 1-week fixed-dose period, the tramadol doses at Visit 4 were 100, 200, and 300 mg/day in 74, 78, and 29 patients, respectively. In the double-blind period, the investigational drug was not taken by one of 79 patients (1.3%) in the tramadol group (excluded from the SAF-DB and FAS-DB) and compliance with the investigational drug during the double-blind period was <70% in three (3.8%) patients.

3.2 Efficacy

Figure 4a shows the Kaplan–Meier plot for the primary endpoint, the time from randomization (i.e., Visit 5) to the documentation of an inadequate analgesic effect. The survival curve was consistently higher in the tramadol group, showing superiority of tramadol over placebo (log-rank p = 0.042). The HR was 0.50 (95% CI 0.25–0.99) in favor of tramadol.

Efficacy endpoints. a Kaplan–Meier plot of time from randomization (i.e., Visit 5) to an inadequate analgesic effect of the investigational drug in the double-blind period. b Changes in Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) values over time for all patients with available data at each week in the open-label period (left) and according to treatment group in the double-blind period (right). The NRS values were averaged over the 3 days preceding each visit and rounded to the nearest integer in individual patients before performing statistical analyses. c Changes in JKOM overall scores over time for all patients with available data at each visit. The markers represent the least-squares mean (LSM) (in b) or the arithmetic mean (in c) at each visit. The LSM (in b) or arithmetic mean (in c) changes from baseline in the open-label period (i.e., Week 0/Visit 1) or from randomization in the double-blind period (i.e., Week 0/Visit 5) are indicated next to each marker. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Full analysis set (open-label and double-blind periods). aPatients were treated for up to 4 weeks in the open-label period: 1–3 weeks in the dose-escalation period (depending on when/if they satisfied the dose-escalation criteria for transition to the fixed-dose period) and the 1-week fixed-dose period (for eligible patients only). CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, JKOM Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure, LSM least-squares mean, NRS Numeric Rating Scale, SEM standard error of the mean

Regarding secondary efficacy endpoints, half the number of patients in the tramadol group (n = 12; 15.4%, 95% CI 8.2–25.3) compared with the placebo group (n = 25; 30.9%, 95% CI 21.1–42.1) experienced an inadequate analgesic effect. The cumulative retention rate was also greater in the tramadol group (83.7% vs. 69.0%). The NRS value decreased progressively during the open-label period with least-squares mean (LSM) changes of −1.0, −1.9, −2.6, and −3.1 at Weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, relative to Week 0 (all p < 0.0001; Fig. 4b). The NRS value (mean ± SD) at randomization (i.e., Visit 5) was 3.0 ± 1.4 in the tramadol group and 3.5 ± 1.5 in the placebo group. After randomization, the NRS values remained broadly stable in both groups without significant LSM changes, except for a significant increase at 1 week in the placebo group (LSM change 0.6; p < 0.0001). The NRS values at each time-point/visit in both periods are reported in Online Resource 2.

The JKOM overall score improved significantly between Visits 1 and 5 (mean change: −11.2, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4c), which was driven by improvements in knee pain and stiffness in knees (−5.5) and condition in daily life (−4.2) (Online Resource 3). During the double-blind period, there was a significant improvement in the JKOM overall score in the tramadol group (−2.1, p = 0.0082), suggesting it improved further during the double-blind period in this group. By contrast, the JKOM overall score increased (i.e., worsened) by 2.1 in the placebo group although this change was not significant (p = 0.0707). During the double-blind period, there were small decreases in the scores for pain and stiffness in knees, condition in daily life, and general activities in the tramadol group, and slight increases in pain and stiffness in knees and condition in daily life in the placebo group (Online Resource 3).

3.3 Safety and Tolerability

In the open-label period, AEs occurred in 80.6% of patients (200/248 patients) (Table 2). AEs (by preferred term) that occurred in ≥5% of patients in this period were nausea in 44.4% (110/248 patients), constipation in 40.7% (101/248), somnolence in 21.4% (53/248), vomiting in 17.7% (44/248), and dizziness in 8.5% (21/248) of patients. One patient experienced a serious AE (hyperventilation) at a tramadol dose of 100 mg/day. The patient recovered following the discontinuation of tramadol and admission to hospital with appropriate treatment. This event was considered to be associated with the investigational drug. Tramadol was discontinued due to AEs in the open-label period in 65 patients (26.2%). AEs that led to treatment discontinuation in ≥5% of patients were nausea in 16.1% (40/248), vomiting in 8.5% (21/248), and constipation in 5.6% (14/248). AEs occurred in 65.7% (163/248), 50.4% (70/139), and 44.4% (20/45) of patients using tramadol at doses of 100, 200, and 300 mg/day in the open-label period (Online Resource 4). The most common types of AEs included nausea, constipation, somnolence, vomiting, and dizziness, which are known AEs for tramadol [33]. The frequencies of AEs did not increase with increasing tramadol dose.

In the double-blind period, AEs occurred in 38.5% (30/78) of patients in the tramadol group and 13.6% (11/81) of patients in the placebo group. There were no serious AEs in the double-blind period. The investigational drug was discontinued due to AEs in 9.0% (7/78) of patients in the tramadol group. The only AE that led to treatment discontinuation in ≥5% of patients was nausea in 5.1% (4/78). AEs did not result in discontinuation of the investigational drug in any patients in the placebo group. AEs occurred in 43.3% (13/30), 34.3% (12/35), and 38.5% (5/13) of patients using tramadol at doses of 100, 200, and 300 mg/day, respectively (Online Resource 5). The frequencies of AEs were low in the double-blind period; only nausea, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, and constipation were reported in two or more patients at any dose of tramadol.

3.4 Drug Dependency

The drug dependency questionnaire revealed no notable differences in the percentages of patients who answered “no” to each question between the placebo and tramadol groups (Online Resource 6). Over 75.0% of patients reported “no” to each question in both groups in the double-blind period. Furthermore, among 87 patients who did not enter the double-blind period, over 87% reported “no” for each question (Online Resource 7).

4 Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of twice-daily, sustained-release tramadol tablets in patients with chronic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis that was difficult to treat with nonopioid analgesics, such as NSAIDs. The results showed that the time to onset of inadequate pain relief in the double-blind period was significantly longer in the tramadol group than in the placebo group, and the cumulative treatment retention rate was higher in the tramadol group. The NRS value and JKOM scores improved during the open-label period and were maintained in the tramadol group during the double-blind period, whereas slight worsening of these endpoints occurred in the placebo group. It is likely that the magnitudes of differences in NRS and JKOM in the double-blind period would have been greater if patients were not withdrawn from the study due to inadequate analgesic effects.

The LSM change in the NRS value during the open-label period was − 3.1. Based on data from ten studies comprising 2724 patients (including patients with osteoarthritis), Farrar et al reported that a decrease in NRS values of at least 2 points from baseline is a clinically important difference [32]. Thus, the improvement in the open-label period in the present study is likely to indicate a clinically meaningful improvement in pain. This was accompanied by an improvement in the JKOM overall score of − 11.2, which was driven by an improvement in pain and stiffness in knees (− 5.5) and the condition in daily living (− 4.2). These results may suggest that the improvement in pain reported during the open-label period was accompanied by decreased stiffness and greater ability to perform general activities. Exercises and physical activity remain the cornerstone for managing the symptoms of osteoarthritis [6, 7, 9], but pain is a major barrier, resulting in a sedentary lifestyle. Thus, the pain relief provided by tramadol in the open-label period and maintained in the double-blind period allowed the patients to increase their activities and ultimately improve their quality of life. Indeed, the JKOM score tended to worsen in the placebo group during the double-blind period, with a significant improvement in the tramadol group.

Overall, these findings are consistent with those of prior studies of patients with pain associated with knee osteoarthritis [14, 16, 18, 34, 35], supporting the potential use of tramadol in this setting. However, it is important to consider that the earlier studies predominantly used extended- or sustained-release formulations of tramadol, administered once daily, that slow the release of the drug (and hence delay its metabolism to the highly active metabolite desmethyltramadol) [25,26,27]. These formulations did not show comparable pharmacokinetics, and differences in their pharmacokinetic properties should be considered when choosing the appropriate formulation for individual patients. Thus, formulations containing a sustained-release component with an immediate-release component have been developed to improve the pharmacokinetic profile of tramadol [26,27,28]. The bilayer formulation used in the present study comprises approximately 65% sustained-release and 35% immediate-release tramadol. This formulation provides a rapid increase in the circulating concentrations of tramadol and the M1 active metabolite after a single dose, with stable trough levels after multiple doses (Fig. 1) [28]. It is anticipated that this pharmacokinetic profile will translate into improved pain relief throughout the day.

The present study also examined the safety and tolerability of tramadol in the open-label and double-blind periods. The frequency of AEs was quite high in the open-label dose-escalation period. Although the frequency of AEs was lower in the double-blind period, AEs were more frequent in the tramadol group than in the placebo group, as would be expected. Like other opioid analgesics [10, 14, 16, 18], the most frequent AEs were nausea, constipation, somnolence, vomiting, and dizziness. These AEs led to the discontinuation of treatment, particularly in the initial open-label period. The rate of AEs was quite high, in part because prophylactic administration of antiemetics or laxatives was prohibited in the study protocol. This approach was chosen to help investigate the safety and tolerability of tramadol. However, once a patient experienced these AEs, they could start taking an antiemetic or laxative. The lower incidence of AEs reported in the double-blind period may indicate that patients became accustomed to tramadol. Patients who were unable to tolerate it likely discontinued treatment early. In real-world settings, laxatives or antiemetics may be prescribed to minimize these AEs of tramadol. Furthermore, the frequencies of AEs did not increase in a dose-dependent manner in either study period, even for AEs common to tramadol. This may be due to the dose-escalation process, which allowed patients to tolerate higher doses [36]. Nevertheless, patients should be aware of the potential risk of AEs and options to mitigate common AEs, particularly prophylactic administration of antiemetics and laxatives.

Although some immediate-release formulations are administered up to four times per day, it was reported that twice-daily sustained-release tramadol capsules showed better tolerability than immediate-release tramadol capsules administered four times per day, with equivalent efficacy [37]. Meanwhile, the majority of other sustained-release formulations, including other bilayer formulations, are indicated for once-daily administration. Twice-daily administration is expected to maintain stable circulating tramadol concentrations, while reducing the risk of pain aggravation. In other settings, it has been proposed that twice-daily administration may better fit the patient’s daily lifestyle, with administration at breakfast and dinner [38]. For instance, patients using platelet aggregation inhibitors were less likely to miss two consecutive doses of a twice-daily drug compared with missing a single dose of a once-daily drug with a potential impact on clinical efficacy [38]. Similar considerations favoring twice-daily administration were reported in other clinical settings [39, 40], and may also apply to twice-daily administration of tramadol.

To evaluate whether patients enrolled in this study experienced any dependence to tramadol, patients completed a drug dependence questionnaire after the double-blind period, after the open-label period, and at a follow-up observation 2 weeks after discontinuation. Of note, most patients responded “no” to each item, suggesting a low risk of dependency and its associated problems (Online Resources 6 and 7).

Finally, some limitations warrant mention, including the relatively short treatment period, which may not reflect the chronic nature of pain associated with knee osteoarthritis. Longer studies may be necessary to evaluate whether the improvements in NRS values and JKOM scores are maintained for longer, reflecting clinical practice. Furthermore, patients were withdrawn if their analgesic effect was inadequate, favoring the continuation of patients with less-severe pain in the placebo group. This approach likely attenuated the difference between tramadol and placebo in the double-blind period.

5 Conclusions

Sustained-release tramadol tablets with an immediate-release component formulated as a bilayer are suitable for twice-daily administration. This study demonstrated the formulation’s analgesic effects and tolerability, supporting its clinical use for managing chronic pain associated with knee osteoarthritis that is difficult to treat with nonopioid analgesics such as NSAIDs. The frequency of AEs was relatively high in patients prescribed tramadol, partly due to the study design. A lower frequency may be achieved in clinical practice, where patients may be prescribed supportive prophylactic therapies to reduce the frequency of opioid-related AEs, especially nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

References

Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):376–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60802-3.

Mandl LA. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: clinical. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(3):359–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.11.001.

Trouvin AP, Perrot S. Pain in osteoarthritis. Implications for optimal management. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(4):429–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.08.002.

Pereira D, Ramos E, Branco J. Osteoarthritis. Acta Med Port. 2015;28(1):99–106. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.5477.

Leyland KM, Gates LS, Sanchez-Santos MT, et al. Knee osteoarthritis and time-to all-cause mortality in six community-based cohorts: an international meta-analysis of individual participant-level data. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(3):529–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01762-2.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(2):149–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24131.

Yeap SS, Tanavalee A, Perez EC, et al. 2019 revised algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis: the Southeast Asian viewpoint. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(5):1149–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01834-x.

Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(8):523–6.

Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(6):568–78. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.22171.

O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(6):331–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.004.

Aweid O, Haider Z, Saed A, Kalairajah Y. Treatment modalities for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of safety. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2018;26(3):2309499018808669. https://doi.org/10.1177/2309499018808669.

van Laar M, Pergolizzi JV Jr, Mellinghoff HU, et al. Pain treatment in arthritis-related pain: beyond NSAIDs. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:320–30. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874312901206010320.

Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17002. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.2.

Babul N, Noveck R, Chipman H, Roth SH, Gana T, Albert K. Efficacy and safety of extended-release, once-daily tramadol in chronic pain: a randomized 12-week clinical trial in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.11.006.

DeLemos BP, Xiang J, Benson C, et al. Tramadol hydrochloride extended-release once-daily in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip: a double-blind, randomized, dose-ranging trial. Am J Ther. 2011;18(3):216–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181cec307.

Fishman RL, Kistler CJ, Ellerbusch MT, et al. Efficacy and safety of 12 weeks of osteoarthritic pain therapy with once-daily tramadol (Tramadol Contramid OAD). J Opioid Manag. 2007;3(5):273–80. https://doi.org/10.5055/jom.2007.0015.

Gana TJ, Pascual ML, Fleming RR, et al. Extended-release tramadol in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(7):1391–401. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079906x115595.

Malonne H, Coffiner M, Sonet B, Sereno A, Vanderbist F. Efficacy and tolerability of sustained-release tramadol in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2004;26(11):1774–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.11.005.

Sorge J, Stadler T. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy and tolerability of tramadol 100 mg sustained-release tablets and tramadol 50 mg capsules for the treatment of chronic low back pain. Clin Drug Investig. 1997;1997(3):157–64.

Vorsanger GJ, Xiang J, Gana TJ, Pascual ML, Fleming RR. Extended-release tramadol (tramadol ER) in the treatment of chronic low back pain. J Opioid Manag. 2008;4(2):87–97. https://doi.org/10.5055/jom.2008.0013.

Lasko B, Levitt RJ, Rainsford KD, Bouchard S, Rozova A, Robertson S. Extended-release tramadol/paracetamol in moderate-to-severe pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with acute low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(5):847–57. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2012.681035.

Park YB, Ha CW, Cho SD, et al. A randomized study to compare the efficacy and safety of extended-release and immediate-release tramadol HCl/acetaminophen in patients with acute pain following total knee replacement. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(1):75–84. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2014.975338.

Pergolizzi JV Jr, Taylor R Jr, Raffa RB. Extended-release formulations of tramadol in the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12(11):1757–68. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2011.576250.

Barkin RL. Extended-release Tramadol (ULTRAM ER): a pharmacotherapeutic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic focus on effectiveness and safety in patients with chronic/persistent pain. Am J Ther. 2008;15(2):157–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e31815b035b.

Kizilbash A, Ngô-Minh CT. Review of extended-release formulations of Tramadol for the management of chronic non-cancer pain: focus on marketed formulations. J Pain Res. 2014;7:149–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/jpr.S49502.

Angeletti C, Guetti C, Paladini A, Varrassi G. Tramadol extended-release for the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. ISRN Pain. 2013;2013:245346. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/245346.

Mongin G. Tramadol extended-release formulations in the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(12):1775–84. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.7.12.1775.

Twotram® (tramadol) tablets, 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg; Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Interview Form, January 2021 (4th Edition). Available at: https://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/interview/1/530288_1149038G2026_1_060_1F.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2021. (In Japanese)

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780290816.

Akai M, Doi T, Fujino K, Iwaya T, Kurosawa H, Nasu T. An outcome measure for Japanese people with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(8):1524–32.

Sugita T, Kikuchi Y, Aizawa T, Sasaki A, Miyatake N, Maeda I. Quality of life after bilateral total knee arthroplasty determined by a 3-year longitudinal evaluation using the Japanese knee osteoarthritis measure. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(1):137–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-014-0645-9.

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00349-9.

Langley PC, Patkar AD, Boswell KA, Benson CJ, Schein JR. Adverse event profile of tramadol in recent clinical studies of chronic osteoarthritis pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):239–51. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990903426787.

Burch F, Fishman R, Messina N, et al. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy of Tramadol Contramid OAD versus placebo in patients with pain due to osteoarthritis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(3):328–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.017.

Florete OG, Xiang J, Vorsanger GJ. Effects of extended-release tramadol on pain-related sleep parameters in patients with osteoarthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(11):1817–27. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.9.11.1817.

Tagarro I, Herrera J, Barutell C, et al. Effect of a simple dose-escalation schedule on tramadol tolerability: assessment in the clinical setting. Clin Drug Investig. 2005;25(1):23–31. https://doi.org/10.2165/00044011-200525010-00003.

Raber M, Hofmann S, Junge K, Momberger H, Kuhn D. Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of Tramadol 100 mg sustained-release capsules in patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain. Clin Drug Investig. 1999;17(6):415–23. https://doi.org/10.2165/00044011-199917060-00001.

Vrijens B, Claeys MJ, Legrand V, Vandendriessche E, Van de Werf F. Projected inhibition of platelet aggregation with ticagrelor twice daily vs. clopidogrel once daily based on patient adherence data (the TWICE project). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):746–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12275.

Bialer M. Extended-release formulations for the treatment of epilepsy. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(9):765–74. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200721090-00005.

Flexner C, Tierney C, Gross R, et al. Comparison of once-daily versus twice-daily combination antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naive patients: results of AIDS clinical trials group (ACTG) A5073, a 48-week randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(7):1041–52. https://doi.org/10.1086/651118.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participating patients, the medical institutions in Japan, investigators, sub-investigators, and hospital staff, as well as all persons concerned for their cooperation in conducting this study. The authors also thank Dr. Nicholas D. Smith (EMC K.K.) for medical writing support, which was funded by Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Conflict of Interest

Shinichi Kawai, Satoshi Sobajima, and Masashi Jinnouchi have received research grants from Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Hideshi Nakano, Hideaki Ohtani, Mineo Sakata, and Takeshi Adachi are employees of Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at all 24 participating institutions.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written informed consent. The following investigators gave consent to be named in this report: Atsuyoshi Samura (Hanazono Orthopedic Internal Medicine, Saitama), Akira Kobayashi (Kobayashi Orthopedics, Saitama), Michio Inoue (Inoue Orthopedics, Saitama), Hisayuki Izaki (Otakibashi Orthopedics, Tokyo), Shinichi Yamaguchi (Gonohashi Clinic, Tokyo), Masahiro Ishii (Sakaue Orthopedic Plastic Clinic, Tokyo), Masashi Jinnouchi (Nishi Waseda Orthopedic Surgery, Tokyo), Hisayuki Miyajima (Meguro Yuai Clinic, Tokyo), Masayo Kato (Ando Orthopedics, Kanagawa), Hiroaki Shibata (Shibata Orthopedics, Kanagawa), Shinichi Katsuo (Fukui General Hospital, Fukui), Katsunori Mizuno (Fukui General Clinic, Fukui), Kiyoshi Miura (Kanai Hospital, Kyoto), Satoshi Sobajima (SOBAJIMA Clinic, Osaka), Shinichi Yamaguchi (Yamaguchi Clinic, Osaka), Takehiro Nishimura (Suita Municipal Hospital, Osaka).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

Data curation: M. Sakata, T. Adachi. Formal analysis: T. Adachi. Investigation: S. Sobajima, M. Jinnouchi. Methodology: S. Kawai, H. Ohtani, M. Sakata, T. Adachi. Project administration: H. Ohtani. Resources: S. Sobajima, M. Jinnouchi. Supervision: S. Kawai, H. Nakano, H. Ohtani. Visualization: H. Ohtani. Writing – original draft: S. Kawai, H. Nakano, H. Ohtani, M. Sakata, T. Adachi. Writing – review and editing: all authors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available on the journal’s website.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawai, S., Sobajima, S., Jinnouchi, M. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tramadol Hydrochloride Twice-Daily Sustained-Release Bilayer Tablets with an Immediate-Release Component for Chronic Pain Associated with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Treatment-Withdrawal Study. Clin Drug Investig 42, 403–416 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-022-01139-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-022-01139-5