Abstract

Western and Central Pacific (WCP) tuna fisheries form part of a broad and complex social and ecological system (SES). This consists of interconnected elements including people (social, cultural, economic) and the biophysical environment in which they live. One area that has received little attention by policy makers is gender. Gender is important because it deepens understandings of behaviours, roles, power relations, policies, programs, and services that may differentially impact on social, ecological, economic, cultural, and political realities of people. This paper contributes a “first step” to examining gender issues in WCP tuna SES. Women’s roles in WCP tuna SES in Fiji are explored and an evaluation of the impact fisheries development policy has on gender equality over the past two decades is revealed. Three key findings emerged from interviews, focus group discussions, and observations: 1) traditional gendered roles remain where women are marginalised in either invisible or low-paid and unskilled roles, and violence is sanctioned; 2) gender mainstreaming of policy and practice remain simplistic and narrow, but are transitioning towards more equitable outcomes for women; and 3) failure to consider gender within the context of WCP tuna SES leads to unintended outcomes that undermine potential benefits of the fishery to broader society, especially to women. A multifaceted approach is recommended to integrate substantive gender equality into SES-based approaches. This research argues educating and getting women opportunities to work on boats falls short of redressing inequality and injustice that is embedded in the social, political, and economic status quo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Western and Central Pacific (WCP) tuna fisheries form part of much larger social and ecological system (SES). These fisheries contribute just over half of the world’s tuna supply while also supporting Pacific island countries’ economies (Williams & Ruaia 2020), food security (Pilling et al. 2015), and sovereignty (Hanich et al. 2010). Developing policies that consider these broader SES and their complex interaction is important. Until recently, however, research on WCP tuna fisheries has focused primarily on biology, stock assessment, and environmental and climate research, with scant attention to gender or the gendered dimensions of fisheries (Evans et al. 2015; Keen et al. 2018; Moore et al. 2020). To date, social research on tuna fisheries has focussed on human rights issues on board vessels and is considered gender blind (Finkbeiner et al. 2017) or focussed on the roles of women in tuna processing factories (Prieto-Carolino et al. 2021). This excludes women’s participation onshore in pre- and post-harvest activities and in reproductive and unpaid support roles. The lack of research into the role of women indicates their social and political marginalisation leaving them socially and economically disadvantaged (Bavington et al. 2004). A growing body of evidence reveals women play key roles in contributing to food security through the harvest and processing of fish, linking poverty reduction and food and nutrition security to Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 (Agarwal 2018; Harper et al. 2013).

SES is a concept focused on the interconnectedness of social and ecological systems (Folke et al. 2005). SES networks are inherently complex and becoming increasingly open because of globalisation (Avriel-Avnia & Dick 2019; Costanza et al. 2014). The WCP tuna SES is no exception, with multiple species of tuna harvested across a vast ocean by distant water fishing nations and Pacific island countries using multiple fishing gear types to access fish in shallow and deep waters. Globalisation compounds complexity and intensifies the disconnect between regions where fish are harvested and consumed (Avriel-Avnia and Dick 2019). Changes to the SES occur across multiple temporal and spatial scales and through multiple SES components, which are sometimes rapid and unpredictable. Moreover, unintended consequences of policy and development occur because many of the relationships, processes, and functions of the system are unknown. This uncertainty not only challenges sustainability of the resource and broader ecosystems, but also presents risks for Pacific Small Island Developing States reliant upon the tuna SES for their wellbeing and livelihood.

Research focused on exploring the role of women in WCP tuna SES can be useful for examining behaviours, gender roles, power relations, policies, programmes, and services that may differentially impact on social, ecological, economic, cultural, and political realities of people (Fortnam et al. 2019; Kawarazuka et al. 2017). We focus on gender relations and how the social construction of gender influences how people relate to one another and, in an SES context, to their ecosystem (Delgado-Serrano and Semerena 2018). Power is integral to these processes as it shapes and coproduces these gender relations (Delgado-Serrano and Semerena 2018). Power is “a social relation built on an asymmetrical distribution of resources and risks” (Hornborg 2001, p. 1; Paulson et al. 2003). Paying attention to gender can broaden understanding of SES networks and how unintended consequences occur.

Research focused on gender and fisheries identifies the male-centric nature of fisheries, the gendered division of roles, and how gendered roles are differentiated spatially and according to resource use (de la Torre-Castro et al. 2017; Fortnam et al. 2019; Prieto-Carolino et al. 2021; Williams 2008). For example, men fish “far and deep” while women stay close to shore (e.g. via gleaning, handlining; (Fortnam et al. 2019)). These generalised assumptions are increasingly challenged by researchers seeking a more nuanced approach to gender in fisheries beyond descriptive accounts of women’s (and men’s) contributions to national economies. Indeed, a shift to consider gender enables greater recognition of the diverse ways in which women participate in, and contribute to, fisheries at multiple scales. As part of this shift, researchers have considered the roles played by women in both historical and contemporary fishing contexts. For example, Manez and Pauwelussen (2016) report research in Oceania dating back to the 1920s revealed women who fished and dived had equal abilities to men, though this varied across Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesian cultures (Manez and Pauwelussen 2016).

Research has considered the roles of women in tuna-processing factories (Prieto-Carolino et al. 2021), women as intermediaries and financiers of fishing expeditions in Ghana, West Africa (O’Neill et al. 2018), and the gendered division of labour whereby women occupy roles requiring attention to detail, receive less money than men, and women’s experiences of sexual harassment (Prieto-Carolino et al. 2021). Moreover, research focused on fisheries governance with roots in equality, such as Ghana’s improved gender policy in fisheries, found increased capacity, confidence, and engagement of women in fisheries management (Torell et al. 2019).

Diffusion of gender into national level policy of Pacific island countries is difficult. In a review of gender policy diffusion in the Pacific region, Song et al. (2019) reveal minimal implementation of global level gender-focused policy commitments in national level policy by Pacific island countries due to a lack of willingness, interest, and importance placed on gender equality in fisheries. This is not confined to Pacific island countries or resource types, however, as Acosta et al. (2019) highlight gender policies within climate change and agriculture sectors of Uganda are watered down at the national level and through policy cycles. Okereke (2008) identify how the diffusion of global equity norms relies on the extent to which norms align with neoliberal ideas and structures. Lawless et al. (2020) highlight how social meta-norms (e.g. human rights, gender equality, equity and environmental justice) face multiple drivers that affect the process of policy diffusion. Drivers include compliance mechanisms, economic benefits, functional interactions, institutional normative environment, norm source, norm issue framing, cultural resonance, and social temper. For example, compliance mechanisms (e.g. treaties, policies and regulations) are challenged by gender equality, equity, and human rights scholars for their ambiguity and their lack of specific obligations and have seen shifts toward soft laws such as codes of conduct or voluntary guidelines (Lawless et al. 2020; Okereke 2008). These “soft laws” are arguably easier to establish and change, but are more effective when coupled with hard law rules. Soft regulatory approaches such as advocacy, encouragement, raising awareness, and benchmarking in the education sector were identified to be successful in New Zealand’s strategy for gender policy (Casey et al. 2011). Lawless et al. (2020) provide important insights into gender policy strategies and frameworks and for gaining necessary buy-in from industry, government, and regional fisheries agencies.

Although there has been more attention given to gender in fisheries management and governance in recent years, fisheries lag behind other fields such as development studies (Desai and Rinaldo 2016; Nightingale 2017; Oberhauser 2017); agriculture (Acosta et al. 2019); education (Manion 2016); water (Khalid Md and Huq 2018); and feminist political ecology (Paulson et al. 2003; Rocheleau 2008; Rocheleau and Edmunds 1997; Rocheleau et al. 1996; Sultana 2011). Relevant learnings that can be applied to fisheries include the need for flexibility in policy and practice to allow for the multiple ways gender can be contextualised through intersections with age, marital status, poverty, and health status. This will avoid interactions that might deepen fisher’s and their family’s vulnerability to negative impacts from the tuna industry. This is highlighted in Alexeyeff (2020) who notes the complexity of intersections between age, socio-economic status, as well as hereditary rank, and argues that gender interventions often produce new forms of inequality and obscure others.

Development projects to improve gender equality focused on financial and technical developments are argued to fall short of empowering women (Underhill-Sem et al. 2014). This paper responds to the gender gap in fisheries research by examining the multiple roles of women in WCP tuna fisheries using Fiji as a place-specific study. Drawing on a range of theoretical perspectives, including development theory, gender studies, and feminist studies, we consider how gender shapes, defines, enables, or constrains women’s engagement and agency in fisheries-based development premised on economic growth, social development, and wellbeing. To accomplish this, we use a transdisciplinary SES framework (developed in Syddall et al. (2021) and applied here) to elucidate the role of women, and the gender dimensions of WCP tuna SES in Fiji. This paper shows 1) the persistence of gender-based stereotyping and implications for women and gender-based violence; 2) the limitations of gender mainstreaming policy and practice despite evidence of a transition towards more equal outcomes for women; and 3) the potential for unintended outcomes due to a failure to consider gender within the context of WCP tuna SES. We give attention to understanding power relations between fishers located within households, communities, industry, and wider scales but also between women and men.

Place-specific study: Fiji’s tuna fishing industry

Starting in 1970s, large-scale commercial tuna fishing in Fiji was late to develop compared to the rest of the WCP region (beginning in the first half of the twentieth century) (Barclay 2014). Prior to this development, Fiji’s traditional and commercial fishing was focussed inshore (DeMers and Kahui 2012; Gillet 2007). Fijian Government and industry has grasped its geographical opportunity (a south Pacific hub due to its geographic location) and since 2000 has aimed to develop the necessary infrastructure and logistics networks to encourage tuna vessels in the region to come to Fiji (Barclay and Cartwright 2007). Fiji’s national longline fleet predominately targets albacore and in 2018 was made up of the following: 13 vessels less than 21 m in length targeting the fresh sashimi market; 36 21–36-m vessels using slurry and freezers for 3 weeks to 2-month fishing trips; and 46 vessels that are greater than 30 m using freezers that targets albacore, spending more than three months on each trip in and outside of Fiji’s EEZ. Nine of these were charter vessels.

Fiji’s largest cannery is PAFCO based on the island of Levuka. It plays an important role in the economy through the manufacture of canned tuna, as the largest employer in Levuka, and a key economic driver for the Lomaiviti Province. While Fiji’s fishing grounds are not as productive as their Pacific counterparts, they provide a more suitable business environment for foreign countries to invest due to their adequate freight connections, infrastructure, and labour force. This is due to its larger and diversified economy, including tourism that connects the country well to the Pacific and beyond (Mawi 2015) and provides a range of opportunities for employment and for direct and indirect involvement in tuna fisheries across the supply chain.

Materials and methods

A mixed-method, place-specific, case study approach was applied to conduct research in 2018 to 2020. The identification and selection of Fiji as a case study to explore gender in relation to tuna fisheries was determined based on expert opinion of research participants. Participants including WCP fisheries managers, independent consultants, and NGO representatives highlighted the important and increasing roles that Fijian women play in the supply chain (e.g. marketing, processing), current gender-based issues that required further investigation but also noted Fiji as being the home base for gender experts and NGOs such as the Women in Fisheries Network. The place-specific study included a 2-week visit in May 2019 to Fiji’s capital Suva and two small villages, Waiqanake and Kalekana. Research questions included the following: what role(s) do women play in tuna fisheries in Fiji; and how has the development of the fishery impacted these roles? Particular attention was given to understanding who benefits from tuna fisheries development and associated policies, and what the unintended impacts are on women.

Nineteen semi-structured interviews were undertaken with representatives of Fiji’s tuna fishery, who were identified using snowballing techniques. Participants included industry representatives, independent consultants, regional fisheries managers, non-governmental organisations (NGO), academics, recreational fishers, and fishers in Waiqanake Village. One particular NGO representative, Pacific Dialogue (an NGO dedicated to preventing human trafficking in Fiji), was instrumental in locating fishers and fisher’s wives within villages close to Suva, organised meetings, and translated Fijian as well as facilitated the cultural protocol (e.g. sevu sevu ceremony performed for gaining entrance into a Fijian village). Due to the economic, cultural, and political ties of the WCP tuna fishery and the application of snowballing techniques, this led to interviews with observers and fisheries managers from other countries including Federal State of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Tonga. These participants undertook observer training in Fiji or managed WCP tuna fisheries at the regional level. Data collected from these interviews therefore were used to understand and analyse the wider WCP tuna SES.

A semi-structured focus group was conducted with six women from Kalekana Village. This village is close to industry ports and therefore a target of recruiting agents for longline fishing vessels (or via word-of-mouth). Participants were from varied backgrounds, nationality, age, or other identities. Key discussion points included their family member’s employment, stories of their experience on tuna fishing vessels, and the impact of tuna fisheries on the local communities, the women’s lives, and their families. During this focus group, the SES network was imagined and drawn together on paper to explore their role in tuna fisheries. Because these women were indirectly involved in tuna fisheries, this was a useful exercise for the women to see how they fitted within the wider WCP tuna SES.

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in English with the assistance of interpreters, who were on hand to clarify statements for participants and the researcher. Following the interviews and focus groups, the lead researcher met with the interpreter to clarify what was discussed including the translation of terms. Participants’ quotes used in this paper have been translated into English but have not been edited.

Data were also collated from primary and secondary sources from country reports, scientific journals, and reports from science providers and other research or NGOs and field observations were collated.

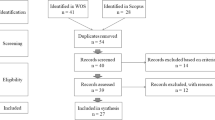

Interviews and focus group discussions were transcribed and inductively coded using nVivo 12 to identify key themes. In addition, data were coded for language that suggested relationships such as “dependence” as well as stories about impacts. A matrix applying a SES framework was used (developed and outlined in Syddall et al. (2021); see Fig. 1) to explore gender with a focus on gendered roles, policy and governance, and social and cultural norms. Using the matrix, a structured approach was used to examine (a) the state of the SES; (b) interlinkages; and (c) changes. Data were cross-referenced with key drivers of the SES identified in Syddall et al. (2021) (Fig. 1). Key drivers include scale (geographical space, institutions, networks), power (power relations between fishers located within households, communities, industry, and wider scales), knowledge (e.g. indigenous, technical, scientific), energy (e.g. biophysical, fossil fuel), and equality. The matrix in Fig. 1 provided a systematized approach to examine gender impacts of the WCP tuna SES on women and men.

SES analysis matrix to explore gender within Fiji’s tuna fishery (adapted from Syddall et al. 2021)

Results

Gendered direct and indirect roles within the WCP tuna SES

Gender-based issues, including gender-based stereotyping and gender-based violence, were found in roles that are directly and indirectly involved in Fiji’s tuna SES. Overall, Fiji’s tuna fishery is “women intensive but male dominated” with women workers consistently over-represented in low skilled, poorly paid, undervalued positions while men dominate more powerful (i.e. higher skilled, better paid, more valued) positions.

Figure 2 shows Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) 2016–2018 data reporting the proportion of women in the most visible roles within the supply chains—processing, harvest, observer, and public sector. Total employment of men and women within these roles in Fiji in 2018 was 4,193 representing 19% of the Pacific region’s employment in tuna industries. Of this, 1,432 or 34% were women. Women dominated processing and ancillary services roles where women represented 61% (1,368) and men 39% (875) of these roles. Men were 100% employed in all other roles including at-sea harvesting, observers, and 73% in public sector roles were men. As shown in Fig. 2, there have been no substantive changes over time to these roles. In terms of indirect and less visible roles, no data exists to summarise those involved. Key drivers impacting the WCP tuna SES, that often have negative outcomes for women were revealed and include price (received for tuna and paid for fuel, labour, and bait), tuna availability (driven by climate fluctuations and fishing), market access (MSC certified, tariffs), and political (in)stability.

The proportion of women employees in roles (where data are known) in tuna fishery in Fiji and FFA PIC member countries from 2016 to 2018. Notes: 2019 data for Fiji was provisional for Fiji and therefore excluded. ‘FFA PIC member countries’ includes the 15 FFA PIC members: Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu

At-sea roles

At-sea roles are almost exclusively men on board tuna fishing longline vessels; however, this research revealed women were beginning to occupy these roles. Ten women were reported by industry representatives to work as crew for New Zealand owned Solander Limited (seven women) and Fijian owned Fiji Fish Marketing Group Limited (Fiji Fish; three women, Table 1), representing 0.6% of the total employment of the harvesting sector in Fiji. Women are also becoming observers on board tuna longline vessels. Upskilling (inhouse, industry-led and through the Fiji Maritime Academy) has meant there are opportunities for women to go to sea on board tugboats and longline vessels. The Fiji Fish representative said women enjoyed their roles as deckhands and work in the icehouses on board. A change of culture was reported where “it’s definitely changed the attitude of the male crew having a female crew on board, in a good way, the boys, they end up treating her like their sister, you know how close the Fiji families are” (Fiji Fish Interviewee, Fiji, 2019).

Barriers remain to women in harvesting roles including cultural beliefs and norms, on board conditions, particularly on smaller longline vessels, and the length of fishing trips that continues to deter women from joining as crew members, observers, or captains. In Fiji, longline vessels are also notoriously bad for workers’ conditions with shared facilities (sleeping, eating, bathing) or no facilities (bathrooms may be absent on smaller vessels). Women who are studying for their Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Fishing Vessel Personnel qualifications are impacted by these constraints and cannot get sea time on fishing vessels. On the Fiji Fish’s larger vessels, there are toilets available for the women; however, all facilities are shared, including the bunks. Participants also reported instances where women were assaulted and harassed while on board vessels.

A PNG observer identified and interviewed through an interviewee from the Women in Fisheries Network commented on her experiences on board a purse-seine vessel where she had been attacked in 2003. While generally being “treated the same” on board by crew, this observer noted the attacker who was a PNG national young crew member “had no experience with female observers before.” Purse-seine vessels were noted by Fiji industry representatives and other interviewees to provide better living standards (e.g. separate facilities). Nevertheless, this did not deter the assault where she was “strangled from behind with rope” because the attacker wanted her camera that had photos of illegal fishing activity. Moreover, while the number of women on vessels are low in Fiji due to barriers to get on these boats, this was an example of where even if other barriers are removed, gender-based violence can still deter involvement.

Post-harvest roles

Regionally, and in Fiji, women’s involvement in the offshore fisheries sector has been predominantly in the processing and post-harvest sector (Fig. 2, Table 1). In small-scale fisheries, participants highlighted women’s role was selling fresh and value-added reef fish (and FAD caught tuna, e.g. Rakiraki) in markets, roadsides, and other outlets. In larger scale industrial fisheries, companies hiring the most women within Fiji’s tuna-processing sector include PAFCO, Viti Foods, and Tri-Pacific (Industry Interviewee, Fiji, 2019). PAFCO is the largest employer of women in the tuna industry in Fiji (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008). In 2017, women represented 64% of the total employees at PAFCO, primarily in production roles but also in “back office” roles (664 of the 1,036 workers) (Parliament of the Republic of Fiji Standing Committee on Economic Affairs 2019). In an earlier study, jobs held by women included butchery, canning, cleaning, drivers, labellers, moulders, skinners, sorters, supervisors, unloaders, mechanics, and day carers (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008). Male-dominated roles in PAFCO included skinning of the fish whereas women dominated the processing lines (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008). Ninety percent of workers at PAFCO were non-salaried women on an hourly paid rate (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008). Workers were then estimated to earn between F$2.75 (floor workers) to F$3.50 (senior staff) per hour. These rates are influenced by a combination of the minimum wage, marketplace, and employee-employer bargaining (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008). Dominance of women in processing may be due to men refusing to undertake “monotonous and demeaning” tasks whereas women who are unskilled, accept lower wages, and have minimal education are more willing and see these jobs as opportunities for earning income for the family (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008).

Conversely, companies including Solander, Golden Ocean, and Fiji Fish were reported by one industry representative to have “mandatory physical work in their processing factories, lifting and carrying of frozen/fresh fish” and therefore hire more men than women. In 2019, Fiji Fish had 10 women and 10 men (50:50), Golden Ocean had 127 men and 18 women (88:12), and Solander had 13 men and 1 woman (93:7) in their processing and packing departments. A representative of Golden Ocean explained that when hiring factory line workers “we try to get them [sic] men” due to the “dangerous high-risk job.” The representative noted that they do hire women but that they are restricted to “the vacuum machine and [sic] make the easy job for the female, easy careful job for them.” Women hired at Fiji Fish were reported to have generally completed secondary school. No women were reported to own or manage longline vessels at either Golden Ocean, Solander, or Fiji Fish.

Administration and advocacy roles

Several participants acknowledged that women are increasingly taking up fisheries administrative roles and were considered by an independent consultant to be the “bedrock” of fisheries administration. Women traditionally hired as “data entries” (data administrators) in the offshore division within the Ministry of Fisheries, are increasingly being hired in senior management roles (e.g. the Director of Fisheries at the Ministry of Fisheries was a woman). Until the early 2000s, Pacific region fisheries policy was “very much male dominated” (previous Chair of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, WCPFC, Online, 2019).

Regional fisheries manager representatives from the WCPFC and Tonga corroborated changes in hiring practices and workforce composition within national administrations. Both representatives noted the increased participation of women in national administrations, regional organisations, and international forums including in lead delegations. For example, as one participant reported, “it’s no longer a novelty to see an all women delegation” (WCPFC Interviewee, Online, 2019). Although, in reporting their own experiences, they have experienced gender-based stereotyping. For example, one woman participant who at the time was working in an administrative role for Cook Islands Ministry of Marine Resources reported being asked to enter a beauty pageant by her boss. This was at a time when she was considering further studies and therefore felt this made her decision easier. She felt there was generally “quite a lot of chauvinism in some of the fishery’s circles” and linked this to her experience of gender-based stereotype. Another participant reported her experience of “a lot of doubt from others, a lot of scepticism” in her abilities to be Chair (WCPFC Interviewee, Online, 2019). She explained:

I was more determined to prove any doubters wrong, a women couldn’t handle a fishery meeting that I couldn’t handle a commission meeting and I know that people were surprised by the reactions I got because the compliments were always sort of, “oh, good job” kind of like “I am surprised you were able to do it” … I could just tell from the tone of the feedback that there was surprise that I could manage it, but I try really hard not to make generalities and stereotype, but I do feel fairly strongly that women have a stronger skill in multitasking and organising.

Other roles within industry include CEOs, marketing managers, accounts administration, and other administrative roles (Table 1). In FAD fishing villages, such as those in Ra Province, women are also community representatives that monitored the FAD caught tuna catch for the Ministry of Fisheries’ records (Conservation International Interviewee, Fiji, 2019). There are also many women and organisations who lead policy advocacy work in the tuna fisheries domain. This includes the Women in Fisheries Network, established in 1993, which “facilitates networks and partnerships to enable opportunities for women to be informed about all aspects of sustainable fisheries in Fiji and to increase the meaningful participation of women in decision-making and management at all levels of sustainable fisheries in Fiji.” Its focus is on lobbying the government to change policies in relation to their mission. In addition, WWF-Fiji, Pacific Dialogue, Women in Fisheries Network, Conservation International, and other local NGOs advocate for gender equality and equity in tuna and other fisheries.

Less visible roles

Roles indirectly linked to the WCP tuna SES are also less visible than tuna fishery supply chain roles, because less quantitative data exists. Research revealed these roles include sex work and carer roles. Both these roles are excluded from formal labour frameworks (sex work is considered illegal in Fiji and carer work is unpaid) and are not measured in gross domestic product (GDP). Research highlights the negative gendered effects of these roles where women, who typically carried out these roles in the Pacific (Mathew 2019) are more vulnerable to experience social and economic disempowerment (UN Women 2018). For example, sex workers are vulnerable to abuse, violence and health threats such as HIV (Shannon et al. 2009).

Sex work and sex trafficking were described as the “underbelly” and part of the tuna fisheries “fabric” and were one of the more talked-about roles by participants for women (compared to other roles overall), but one with the least amount of data. This is particularly prevalent for Fiji as an important hub of the Pacific shipping and tuna industry. Sex work in the Pacific region is reported in ports where fishing vessels are docked (McMillan and Worth 2017; UNICEF et al. 2006; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2011). The place-specific study in Fiji confirmed this role with stories shared by participants that sex trade and sex work is used as a touristic attraction using hotels/motels and bars for Chinese and other foreign boats to come into Fiji ports for economic growth (Pacific Dialogue Interviewee, Fiji, 2019). A Women in Fisheries Network representative and independent consultant also shared their experience of witnessing schoolgirls working on tuna fishing vessels while in port as sex workers in Kiribati. Sex workers have been associated with the tuna fishery in Kiribati (McMillan and Worth 2019; Vunisea 2005c), Marshall Islands (Vunisea 2005a), and Fiji as well as many other Pacific Island countries (Barclay 2010; McMillan and Worth 2019).

Sex work in tuna fisheries is largely an under-researched area with little concrete evidence (Barclay 2010) and thus gender inequalities are less well known. Earlier research has commented on the social problems experienced by sex workers (unplanned pregnancies, violence, sexually transmitted infections such as HIV, Barclay 2010; Vunisea 2005b). McMillan and Worth (2011) discuss the complexity of issues and argue they are dependent on the livelihoods of the women themselves. For example, women in Kiribati undertake sex roles on board foreign tuna fishing vessels due to “overcrowded living conditions, a culture of hardship, the domestic oppression of women, and the endemic nature of physical and sexual abuse” (McMillan and Worth 2019, p. 1942). In Fiji, studies note the economic, education, family violence context as a key factors driving choices to undertake sex work (McMillan and Worth 2011).

While family members are away for long periods of time, carer roles are exclusively carried out by women. Another important yet overlooked role described by participants included women who are mothers / wives / daughters / sisters to crewmen aboard tuna vessels who are away at sea from two weeks to years at a time. These women reported relying on their family member’s employment in tuna fisheries for income for their household. The interrelationships between these women and their seafaring husband / son / brother / father is complex. Here, we focus on violence perpetrated against men and the flow on impacts this gender-based violence has on men and women’s gender-based roles in the household. Violence is an ambiguous term (Stanko 2003) and is considered contextual based on legal, political, social, cultural, personal, and temporal contexts (Kaladelfos and Featherstone 2014). It also involves acts that result from a power relationship and includes threats and intimidation, neglect or acts of omission (as in the case of men who did not receive adequate access to clean water, sanitation, food, and medical attention) as well as the more obvious acts (physical, psychological, and sexual) (Bott et al. 2005; World Health Organisation 2022). Gender-based violence is commonly discussed and researched in reference to violence against women and girls (Carpenter 2006). The little research that examines gender-based violence against men tends to centre on sexual violence or military violence (Carpenter 2017; Christian et al. 2011; Peretz and Vidmar 2021). We therefore adopt the following definition of gender-based violence, “violence that is targeted at women or men because of their sex and/or their socially constructed gender roles” (Carpenter 2006, p. 83). This paper uses an inclusive definition of gender-based violence to discuss a range of harms that are not currently understood as such within the fisheries industry community.

Professions on board tuna fishing foreign vessels are generally acknowledged as risky and violent. When disaster strikes (men are killed, or kill their boss when their treatment is unbearable, or disappear at sea, or are badly maimed in the course of their work), the event is generally framed within human rights discourse (for example, as part of transnational organised crime (Chapsos and Hamilton 2019)). However, the everyday violence that precedes the most violent acts is documented in “slavery at sea” literature, but not tagged as gender-based violence. We, however, characterise violence on board tuna fishing vessels as gender-based violence, noting that the strong gender divisions of labour in tuna (and other fish) value chains result in certain workspaces that are highly masculine or feminine in their composition (Barclay et al. 2021). Violence by men against men tends to be positioned as a manifestation of hegemonic masculinity (Cornwall and Lindisfarne 2006), along with gender-based assumptions whereby “dangerous” seafaring roles are the domain of men (Fortnam et al. 2019). Cornwall and Lindisfarne (2006) investigate taken-for-granted assumptions regarding men (as an unmarked category) and masculinity (as social construction) to distinguish variants of masculinity and to elucidate how gender and power are negotiated in relation to social interactions. In dismantling hegemonic masculinity, Cornwall and Lindisfarne (2006) also argue the need to problematise the essentialist male/female dichotomy because it does not allow for different conceptions and performances of gender to be recognised and it disregards how cultural and historical context can give rise to gender variants in different places at different times. Thus, they emphasise seeing notions of masculinity (and femininity) as fluid and situational (Cornwall and Lindisfarne 2006). From this perspective, violent acts on board fishing vessels between men are gendered but the fact they are men-to-men is less important than how violence reflects social differences between men with unequal power (driven by economic, social, and racial/ethnic factors), which conditions social interactions from the moment of recruitment and is used to dominate and justify violent acts. Carpenter (2006) asserts this argument by stating that gendered roles (such as seafarer roles in our example) intersect with race, ethnicity, class, and economic status and that these intersections justify the act.

This research revealed men, all in their 20s and 30s, to have been mistreated and/or injured and therefore unable to work, or worse, they have been murdered or died while on the job. Fijian women in focus discussion groups reported injury, death and murder on board Chinese, Fijian, Korean, and Taiwanese vessels typically with mixed nationality crews (including Philippines, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India). The women also referred to the Fijian vessel that sunk during a cyclone and had an all Fijian crew (Pacific Islander deaths on board tuna fishing vessels are reported in Komaisavai and Magick (2019) and include some of these women’s husbands). Violence was also reported by a representative of Fiji Fish, who noted the troubles they encounter from the Taiwanese and Chinese vessels which use its processing facilities. Instances were reported by Fiji Fish representative where murders and stabbings have almost occurred during fights at Fiji Fish premises where alcohol has been involved. The Fiji Fish represented commented on how “they come and drink, and you know, and it’s just all the pressure gets released and they just fight… they are not my crew, they are contracted.”

Women reported how their husbands loved fishing from their early childhood (Focus group, Kalekana Village, 2019). Fishing was valued by men to support their family. However, the impact that tuna fisheries have on men and their bodies and the flow on impacts this has on their families is immense and should not be overlooked. In 2019, Human Rights at Sea showcased the experiences of Josaia Cama, from Waiqanake fishing village who was crew on a CKP Fishing company (south Korean) tuna longliner (Human Rights at Sea 2019). Josaia was also a participant of this study. His experience of forced labour, which led to the loss of all his fingers, is instructive for this study. Forced labour, according to the International Labour Organisation, 1930 (No.29) is “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.” Josaia’s account of his experiences draws attention to how power and social constructions of gender condition social interactions:

we finish the fishing aye … we on the upper deck yeh … They [Taiwanese boatman / supervisor] said for us to go down again into the bottom freezer … you unload and you the job is finished aye … they pull up the ladder, like this aye … this is the second time, I was forced two hours … I was cold … they give us gloves but the cotton gloves to make the work easier … the rest who, the older ones see they have experience in, because … Vaseline and they drink rum to keep them warm, but we had none … the other Fijian boy he was a big man aye, he didn’t want to go in the freezer, he was hiding from the boss … they put the ladder down again and the thing finished. And I start eating I can’t feel my fingers aye so they all numb and it was like someone was banging a hammer … very painful.

Josaia explained how he and two other Indonesian crew were forced to offload frozen tuna from the vessels’ air blast freezer (~ − 40 °C) in Japan (Human Rights at Sea 2019). He described how crew were not normally asked to work in the freezer, only the “iceman”, and that he was given inappropriate protective gear (the “iceman” was given proper gloves but this meant you couldn’t feel the fish), which did not keep his hands warm. This ultimately led to Josaia having all ten of his fingers amputated in Fiji after developing gangrene as a result of severe frostbite. Josaia also reported his contract, a copy of which he never received, stipulated a US$400 per month income (around FJ$800) but he only received FJ$400 per month and he never received his promised bonuses for catching sharks (used for their fins) (Human Rights at Sea 2019). These physical injuries had an impact on his ability to support his family (and therefore also impacted upon his family), as well as his perception of his masculinity and status as a man: “because of my disability I cannot help care for my family as a man should, so Virisila [wife] has had to take on that task as well as doing the jobs women do in a family” (Josaia Cama interview, also reported in Human Rights at Sea (2019)). Women who participated in the focus group and interviews commented on the poor work standards the men had endured including lack of access to clean water, food, and adequate sleep (Focus group, Kalekana Village, 2019). Josaia shared his experience of feeling that his company had taken advantage of him and not paid him properly “because maybe my appearance and my looks, I was discriminated, aye” (Josaia Cama, Waiqanake Village, 2019).

This research reveals that benefits of tuna fishing do not trickle-down to the families of injured crew who are left worse off than if their family member had not gone on the boats in the first place. Fishers and their families reported receiving minimal or no pay for when the fisher was unwell (or dead) and unable to work. After injuries or death, these families reported having not received any support for funerals. Families faced the burden of losing the family income earner along with the grief associated with losing a loved one or having to care for the injured as well as payments for additional medical care. Women were left behind to provide for the family, often with one or more children to look after, and relying heavily on their local qoliqoli (traditional fishing ground) for food and income. Sons of these men, as young as 14 years old, were reported to have left school early to take over their father’s role. Meanwhile, mothers also explained how tuna fisheries affected their children because of social problems such as drug use and prostitution. In one instance, the whole family of a crewman was ostracised from their village because of their inability to contribute to village activities. Some women expressed their regret that they never knew what had happened to their family members or did not find out the fate of their husbands until they went to the company to pick up their husband’s pay cheque. In the case of Fijian Joeli Nailati, a crewman murdered in Solomon Islands while aboard YuhYih no. 12 LL, an investigation by Pacific Dialogue uncovered to his wife that a Chinese man was convicted of his murder and was still serving his sentence.

Some women received government or company compensation of up to FJ$24,000 (US$11,000 current value; for example, in the case where a man had been stabbed to death in 2006). In the case of the sunken vessel, Wasawasa, Fiji Fish compensated with tuna fish and FJ$50 weekly (US$23 current value) from 1997 until 2000 then after the coups, the court ruled that each family was entitled to FJ$15,000 (US$7,000 current value) plus a tuna fish weekly allowance until 2007. No compensation was provided for those families of fishers who had illnesses and died such as loss of wages during the time on board vessels but not working due to illness or death. The women who depended on these men were left unsupported financially and have no alternative but to work harder and longer no matter what the consequence on their bodies, their families, or their qoliqoli.

Gender intersects with other identities such as race and class, which can amplify risks of gender-based violence on board vessels. Recruited women in this research had all lost someone in the tuna fishery or relied on men that had been injured and were unable to contribute to the household or village income and activities. On board fishing vessels, power-relations are unequal and in favour of fishing companies (owners and captains of vessels). Intersectional subjectivities and a risk-taking culture tied to performances of masculinity on board vessels, often amplified by excessive drinking and sexual promiscuity, is confirmed in Allison (2013) who explored masculinity in shipside culture. Moreover, while Fijian-owned longliners with national crew are family oriented, international vessels with mixed nationality crew are predatory.

The industry was perceived by focus group women and fishers interviewed as hiding behind a corporate veil that blanketed human rights violations. This was evidenced by the lack of labour contracts, forced labour, and misinformation on deaths. Women interviewed were unaware of the causes of death, the outcomes of justice, nor did they receive equitable compensation for impacts on their welfare. For the PNG observer assaulted on the purse-seine vessel, due to lack of evidence, her case was dropped after three years, and she never saw the assailant again. Her boss at work provided support but no counselling was offered to her. She says she has got over it in time and still goes out to sea.

Gender, policy, and governance in Fiji

Pacific regional projects such as those developed by FFA (described further below) show some promising approaches including gender diagnosis through to action (e.g. placing gender/women equality on agendas; policy change; strategies and targets set; action resources, formal reporting and accountability). However, gaps remain in mainstreaming gender in regional and national tuna fisheries policies. The WCPFC currently does not have a gender policy or provisions for the inclusion of gender equality in its conservation and management measures (CMMs). WCPFC’s Resolution on Labour Standards for Crew on Fishing Vessels (Resolution 2018–01) includes the minimum labour employment conditions and international human rights standards. A participant who was a former Chair of the WCPFC commented that WCPFC’s Harvest Strategy for Key Fisheries and Stocks in the WCP (CMM2014-06) are still economic and science focussed,

Social and gender issues are just starting to come out in discussions on harvest strategy objectives, management objectives, but I don’t think I could say that there are in any way a focus. The focus is still very much on economics and then informed by the science, but yes social issues are getting more attention and gender issues, gender is really in my experience, a focal point, but in the discussion of harvest strategy management objectives it will come out as discussions progress it just hasn’t been a lot of discussion yet on management objectives. Social issues are definitely there, I think that with more women leading delegations and potentially with a lot of women at FFA you might see gender discussions coming up here (Former Chair of the WCPFPC, Online, 2019).

The comment that gender will “come out” in WCPFC management forums is yet to be seen.

FFA do have gender-focused policies including its 2017 Gender Equity Framework consisting of Pacific Leaders Gender Equality Declaration (2012), The Framework for Pacific Regionalism (2014), and FFA’s Strategic Plan 2014 – 2020, which promotes gender equality and “equitable access to fisheries resources” to “lift the status of women in the Pacific” and “empower them to be active participants in economic, political and social life.” However, while FFA’s Harmonised Minimum Terms and Conditions (revised 2016) includes minimum labour employment and conditions, international human rights standards, and considers ecosystem issues, there is no mention of women or gender (see https://www.ffa.int/system/files/HMTC_as_revised_by_FFC110_May_2019_-_FINAL.pdf).

A local gender expert argued that gender had not been mainstreamed into many policies in the Pacific; however, governments were beginning to realise the importance of considering gender but they “don’t know how to do it” in the absence of appropriate tools and support (Chair of Women in Fisheries Network Interviewee, Fiji, 2019). Consequently, challenges remain in understanding gender-based issues in tuna fisheries. At FFA’s Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) workshop in 2020, Dr Tupou-Roosen (FFA Director, Online, 2019) stated “We need to make every effort to understand the specific barriers faced by women and other marginalised demographic groups in the fisheries supply chain, so policies and practices are more intentionally inclusive.”

Political (in)stability was identified as a key driver of change of Fiji’s tuna SES, often having flow on impacts for women. Up until 2000, the industry was development-driven (as opposed to policy-driven). Alongside policy, Fiji saw a proliferation of women’s networks as a key outcome of the United Nations Decade for women (1975–1985). This included groups such as the Women in Fisheries Network (established 1993) and Fiji Women’s Rights Movement (established 1986).

The purpose of these networks is to bring women together across levels of action to share information and resources and to strategize ways to improve gender equality in Fiji. By 2000, there had been some efforts to promote women’s participation in society and the economy including the Equal Employment Opportunity Policy in 1999 providing Ministries with guidelines and benchmarks from which they could devise their own policies, and the Health and Safety in the Work Place Act 1996 to address women’s health issues in tuna industries (Arama and Associates Ltd. 2000). The Government at the time was also reconsidering its minimum wage policy for factory workers (Arama and Associates Ltd. 2000). However, as many participants discussed, the 2000 coup damaged tuna industries for a period, and halted any social policy development the Labour Government had in mind. Moreover, the coups of 2000 presented considerable uncertainty for the country, including the tuna fishing industry. This period was described as “quiet” by one interviewee as the industry was unsure about the political stability of the country until 2006. While tuna fishing continued, Fijians continued to experience gender-based issues and lacked much-needed support from the Government.

After the coups, the Fijian Government became more policy-centric and adopted policy to develop the port to attract distant water fishing nations to Fiji. However, as some participants noted, the development of the port led to an increase in sex work, which has led to associated negative social impacts. Conversely, a major upside of the coups was Government policies encouraging greater participation by indigenous Fijians in ownership of tuna businesses. Over a decade later, gender equality was still off the agenda in fisheries policy. While emphasis was placed on minimising social impacts in the development of the Tuna Management and Development Plan (2014–2018), the first formal mention of gender was not noted until recently in the draft Offshore Fisheries Management and Development Plan (2021–2026). However, the gender policy within this draft Plan remains simplistic and narrow, and focuses on increasing women’s participation, improving data collection, and promoting achievements made. Although data collection including sex disaggregated data and increasing women’s participation is a step towards gender equality, this is short of a more comprehensive and multi-scalar approach required to achieve gender equality (e.g. multi-level strategies (Lawless et al. 2021); collaborative gender networks (Barclay et al. 2021; Mangubhai et al. 2022)). Gender policies are slowly becoming mainstreamed across Fijian national policy including the 2017 National Development Plan, the 2014 National Gender Policy, and the National Women’s Plan of Action (2010–2019) as part of its international obligations.

NGOs (such as World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Women in Fisheries Network), the tuna fishing industry, and government have worked collaboratively to upskill and increase women’s participation in the tuna fishery. Besides national policy, industry and NGOs also have their own internal gender policies (informal and formal). Industry use in-house and external training for their employees through the Fiji Maritime Academy and The Pacific Community (SPC). Moreover, an NZ Aid programme was reported to require 50% women’s participation in Fiji Maritime Academy training. Companies like Solander and Fiji Fish, in collaboration with Fiji Maritime Academy, provide opportunities for women to gain experience for their training towards becoming a captain (STCW-F and national certificates). Other training programmes are facilitated through FFA and other organisations such as Women in Fisheries Network (post-harvest fisheries training). However, there remains a risk of policies aimed to increase women’s participation in tuna fisheries to expose women to gender-based violence and human rights violations. An Independent Consultant expressed concern about the movement for increasing women’s participation on board tuna vessels, “that’s a fight for gender, but for me, I don’t totally believe in it because you don’t have the safety.”

Culture, a major barrier for gender equality in Fiji

Marine ecosystems were revealed to be fundamentally important in Fijian culture. The marine ecosystem is described as the “cultural glue that maintains the fabric of how they interact with each other” (Conservation International Interviewee, Fiji, 2019). Fijian people’s connection to the ocean and beliefs regarding women’s role in fisheries, households, and the village community underpin women’s roles and access, control, and ownership of tuna resources for food and for income generating activities. The intersection of culture, technology, and women’s biology was discussed by a participant,

Women don’t go on the boats, their supposed to be a taboo, if they go on the boats, there’s no fish, so that has carried on up until now and if they have their menstruation then there will be no fish, all this kind of taboo against women fishing that’s why they’re not really into the big fishing thing (Independent Consultant Interviewee, Fiji, 2019).

This was confirmed by a Ministry of Marine Resources Cook Islands representative who commented on cultural influences and the importance of women’s role in the household and community that ties women to stay “close” to the home and village,

I really think that's cos [sic] of the Pacific culture, in particular, women are sort of underpin [sic] a lot of foundation of our communities so their not only mothers and caregivers but they actually ensure the wellbeing of families and extended families which, as you’ll know, include the wider or broader communities that they live in and so there's this continued need or pull for them to be shore-based more so than any other role (Representative of Marine Resources Cook Islands, Online, 2019).

Interrelations between roles of women in tuna fisheries and their roles in inshore fisheries are complex and are important to consider. The importance of Fijian women’s economic role in communities in fishing have been described in earlier studies (Quinn and Davis 1997). Focus group women discussed the need to rely on their qoliqoli more as a source of food and income while men were away fishing. Moreover, within the tuna industry, cultural challenges also remain for women to enter the labour market and upskill into higher paid roles from the lower paid processing roles. This has been attributed to women being unable to spend the time advancing their career in their traditionally multitasking household, fishing, and customary roles alongside their waged job (Sullivan and Ram-Bidesi 2008).

Women interviewed in this research revealed that they juggled waged work with fishing, carer, village, and household responsibilities. The connection of women’s economic role, health, culture, fishing, and power relations within villages was made by a representative of Fiji Locally Managed Marine Area Network, who also noted women are in water for long periods of time (sometimes 7 am to 2 pm) during which they are exposed to the sun and cold as well as water “covering their womb”. Reflecting on women’s absence in decision making roles in the village, the interviewee noted that women needed to “discuss with men [these issues] and to get traditional leaders on board to support them” in relation to their health and obtaining fishing licences.

Meanwhile, Fijian men’s household and village role has allowed them to access offshore pelagic ecosystems. Tuna fisheries are generally capital intensive and in Fiji are generally accessed by industrial fishing vessels, which are male dominated both in terms of crew, captains, and ownership (Parris 2010). This culture flows throughout the SES. Characterisation of the WCP tuna SES also affirms the technocratic and male-centric culture of the tuna fishery. For example, the fishery’s worker model was described as “masculine” (Independent Consultant Interviewee, Fiji, 2019) and economically focussed. Investors and governments outside of Fiji are complicit in this system because men are identified as economic actors and heads of households. Moreover, science, industry, and policy representatives defined the WCP tuna SES using technocratic approaches to understand its complexity and contextual/socially constructed system and boundaries. Although the tuna fishery is male dominated, men also experience powerlessness (as discussed in Sect. 3.1.4).

Discussion

The findings of this study show that, despite recent attempts to improve gender equality, women directly and indirectly involved in the tuna fishery continue to be affected by gender-based discrimination leading to disadvantage and ongoing inequality (O’Neill et al. 2018; Prieto-Carolino et al. 2021). Moreover, evidence from this research demonstrates unintended outcomes for women because of policy initiatives focussed on addressing inequality and enhancing women’s involvement in tuna fisheries, specifically in the form of gender-based violence.

Gender-based stereotyping, discrimination, and violence are outcomes of culture and globalisation, which are antagonistically interlinked with the WCP tuna SES. Firstly, liberalisation of trade and finance, which provide new economic possibilities, have changed the pace, scale, and dynamic by which marine resources are utilised. Secondly, gendered power relations have been fundamental to the functioning of culture, the household, and the natural resources industry in the Pacific Islands, including Fiji (Murrary 2000; Underhill-Sem et al. 2014).

In Fiji, power relations are partly expressed through cultural-power links and can be described as power between cultures (hegemony; (Gramsci 1971)), but also power within cultures (between individuals or groups of individuals), and its relations to space (Hart 2002). In Fiji, race is reportedly a dominant social marker when compared to gender (Presterudstuen 2019). During interviews and focus groups, participants were most forthcoming on where they were from, and where the crew were from throughout the Pacific. There was a sense of comradery between those who were from other parts of the Pacific Islands compared to those who were considered outsiders such as Taiwanese, Koreans, or Chinese. These two processes (culture and globalisation) have transformed ways in which the marine environment and economy are interlinked with Fijian village life and how women are incorporated. Furthermore, masculinities and femininities in Fijian villages are continually constructed, performed, and negotiated through culture but also, as the research reveals, intersects with wider global and ideological structures of the WCP tuna SES (Presterudstuen 2019; Underhill-Sem et al. 2014).

Fiji has experienced socio-economic impacts that have shaped traditional culture through two distinct waves of globalisation: the “colonial wave” (1870s–1914) and the “neoliberal wave” (1987-present) (Firth 2000). Across the two waves of globalisation, the hierarchy of political economic powers ensued between the Pacific Islands and the rest of the world (and in the context of tuna fisheries, with distant water fishing nations) where they have been a resource supplier stripped of power to influence the terms and conditions of trade. Moreover, the impacts of colonialism, modernisation, and Christian conversion has constructed and altered men and women’s ideals, practices and power structures (Desai and Rinaldo 2016), and, as Presterudstuen (2019) has argued, men’s bodily and social capacities. Tuna fisheries’ development in Fiji was a way for colonial and economic powers of distant water fishing nations such as America, Taiwan, and Japan to exert their influences on regional and national regulations and economies (Havice and Campling 2010). Meanwhile, in the 1980s, women were incorporated into the global marine economy predominately as workers in factories processing tuna fish products for expanding global markets such as America, China, and Japan (Bair 2010). However, gendered power-relations play an important role in shaping patterns of severe labour exploitation within global supply chains such as tuna fisheries. As this research shows, women continue to dominate lower paid and unskilled roles, which is manifested through cultural processes (discussed further below) as well as globalisation that has seen a clashing of the “Fijian way” with a “European way” (or “western way”). This is confirmed in Rodriguez Castro et al. (2016) who argue that women have taken on additional responsibilities without the power of agency where ideas of empowering women into waged work has seen the reinforcement of women as a source of cheap labour.

The interplay between colonial and postcolonial eras, and between different ethnic and cultural groups has shaped the identities of men and women in Fiji villages (Presterudstuen 2019). These global, historically complex, and political, social, and economic processes have reconfigured Fijian tradition and seen the subordination of women (Murrary 2000; Presterudstuen 2019). Male domination and masculine-self identities have often been centred on men’s assigned roles as “bread winners” in families and tribal communities, and in modern societies, the ability to make money (Presterudstuen 2019).

The belief that men are “strong” heads of the household revealed in this research has been identified in other studies that note how cultural values, including strength and humility, are explicitly taught to all Fijian men (Presterudstuen 2019). Cultural values linked to the male body contribute to a complex social order and ethos of authority and hierarchy and have been influenced (modified) by Western or modern culture and norms to generate gender-based stereotypes. Within the WCP tuna SES, these stereotypes can lead to discrimination and violence. For Josaia, his eagerness to support his family by crewing on board a tuna longline vessel was met by forced labour ultimately leading to the loss of his fingers. In this example, alternate conceptions and performances of masculinity that recognise cultural differences and power differentials were not possible or were deemed undesirable because of the persistence of hegemonic masculinity (Cornwall and Lindisfarne 2006). Elsewhere, Pauwelussen (2021) exploration of masculinities and especially transformation of masculinities (and men) in fisheries demonstrates masculinities as performative, embodied and affective whereby masculinity in fishing is provisional and changing rather than a fixed identity. This means fisher bodies, and bodily performances of masculinity, have the potential to transform from muscular and strong bodies to impaired and less mobile bodies, which influences social interactions and mediates social relations. Thus, while much fisheries research has tended to focus on macho-type masculinity and male bodies as strong and risk-taking, Pauwelussen (2021, p. 4) argues the need to look “beyond a hegemonic figure of the “hard-bodied self-contained man” to acknowledge other masculinities. Studies into gender and forced labour in global supply chains, such as the tuna fishery, are limited (LeBaron and Gore 2020). In the case of Josaia, his experience of working in tuna fisheries, a highly (yet narrowly conceived) masculinist and masculinised space, ultimately altered his capacity (as a man) to contribute to the household and village through loss of his wages and an inability to work on village land, which led to his family being ostracised from the village.

The feeling of estrangement articulated by Josaia has also been described in Presterudstuen (2019) with regard to a mining worker who spent time away from the village and who experienced estrangement from village affairs, and loss of respect and connections. For Josaia’s wife, Virisila, Josaia’s injury burdened her with extra responsibilities that her husband was unable to fulfill, while she also had to continue to negotiate power relations in household, community, and economic activities. This experience mirrored those of the women in the focus group who had lost family members and were left to juggle more than their fair share of roles in their household and in their villages.

While efforts have been made to increase women’s involvement in tuna fisheries (administrative, observer, and on board vessel roles), efforts to understand and implement policies to achieve gender equality in tuna fisheries remain in their infancy. Gender equality policy development in Fiji has faced initial international influence from women’s social movements such as the UN Decade for women, giving impetus to establish women’s networks such as the Women in Fisheries Network, but then a period of policy backtracking due to significant political change during the coups.

Gender policy relevant to tuna fisheries since then has developed slowly, in part due to the backlash from the coups but most likely due to a lack in priority and political will from regional bodies such as the WCPFC as well as a lack of understanding how to implement them at the national level. Mainstreaming of gender equality in the Pacific and Fiji has been implemented increasingly across regional and national governance as well as part of donor requirements. Researchers have questioned whether the mainstreaming of gender has led to positive changes in women’s lives (Acosta et al. 2019; Syed and Ali 2019). Gender mainstreaming has been critiqued by development scholars for its universal hegemonic approaches to gender equality representing communities as homogenous (Adusei-Asante et al. 2015; Cornwall and Rivas 2015; Lawless et al. 2021). Further, rhetorical adoption of “shopping list” policies are criticised for their inability to be implemented across geographies and contexts to solve complex, diverse, and evolving issues of inequality (Acosta et al. 2019). Thus, researchers have called for gender-sensitive approaches that are context specific and multi-scalar (international, national, local) (Acosta et al. 2019; Syed and Ali 2019).

Diffusing gender equality into tuna fisheries

Diffusion of gender policies into national offshore fisheries policy in the Pacific has been slow and simplistic (Song et al. 2019) and Fiji is following this trend. This suggests a lack of willingness, interest, and importance placed on gender equality in fisheries. This research has revealed the complex cultural, political, and neoliberal barriers that block diffusion. However, following Lawless et al. (2020) framework for developing buy-in from industry, government, and regional fisheries agencies into gender policy strategies, Fiji and the wider WCP tuna fisheries could be successful in developing a more gender equal WCP tuna SES. This could include 1) “soft” laws including codes of conduct such as WCPFC’s resolutions, advocacy from Fiji’s women network NGOs, and encouragement from government and industry; and 2) “hard” law rules at the national level as well as inclusion of gender equality policy in WCPFC CMM Harvest Strategy (CMM2014-06). Fiji could in the first instance leverage regional efforts of FFA as well as learnings from inshore gender programs such as SPC’s Pacific Handbook for Gender Equity and Social Inclusion in Coastal Fisheries and Aquaculture (https://coastfish.spc.int/en/component/content/article/494-gender-equity-and-social-inclusion-handbook). Other initiatives to promote gender equality policy diffusion could include the development of social ecolabels and application by major markets (including the USA and Europe) to improve compliance.

Conclusion

To date, empirical insights of new environment-social linkages have not been met with equal efforts to reconceptualise these linkages. As such, out of date approaches to fisheries issues continue to be employed in policy and management. These externalise society and the environment to economies, and fail to incorporate critical linkages, such as power relations, class, race, and culture. As this research has revealed, women are not included in these analyses, yet they play important and varied roles in tuna fisheries. This research reveals gendered power relations and inequalities shape workers vulnerability to forced labour, while also revealing the challenges confronting traditional Fijian village women and men, who must navigate new and old ways of the economy, culture, and power-relations. Research and policy remain focussed on economics and science. Although there are attempts at gender mainstreaming across the region, this remains universalistic and simplistic. Moreover, this has not filtered down to support women in villages or on board vessels. There are gaps in gender equality policy across regional and national levels requiring further policy development for meaningful implementation.

A new approach to the empowerment of women in fisheries is urgently needed as well as recognising women as equal economic actors in which they contribute actively in diverse ways across tuna fisheries supply chains and in their family and village lives. To do this, an appropriate and multi-scalar gender policy is required for the tuna fishery, and women must hold active participation in decision making and leadership roles across scales of governance to influence policy and practice. This research has shown that educating and getting women opportunities to work on boats falls short of redressing inequality and injustice that is embedded in the social, political, and economic status quo.

Data availability

Data used in this paper is not available for use by other researchers. Some of the data is protected by the ethical approval conditions of the research, as is usual for qualitative data where the identity of the speaker may be visible even once their name has been removed.

References

Acosta, M., S. van Bommel, M. van Wessel, E.L. Ampaire, L. Jassogne, and P.H. Feindt. 2019. Discursive translations of gender mainstreaming norms: The case of agricultural and climate change policies in Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum 74: 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.02.010.

Adusei-Asante, K., Hancock, P., & Oliveira, M. (2015). Gender mainstreaming and women’s roles in development projects: a research case study from Ghana. In At the Center: Feminism, Social Science and Knowledge (Vol. 20, pp. 175–198). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-212620150000020019

Agarwal, B. 2018. Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 34: 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.07.002.

Alexeyeff, K. 2020. Cinderella of the south seas? Virtuous victims, empowerment and other fables of development feminism. Women’s Studies International Forum 80: 102368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102368.

Allison, E. H. (2013). Maritime masculinities - and why they matter for management. Paper presented at the Conference People and the Sea VII, Amsterdam. https://genderaquafish.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/04-allison-mare-maritime-masculinities.pdf

Arama & Associates Ltd. (2000). Fiji gender impacts related to development of commercial tuna fisheries: a report to the South Pacific Forum Secretariat. South Pacific Forum Secretariat: Rarotonga Cook Islands.

Avriel-Avnia, N., and J. Dick. 2019. Chapter five - differing perceptions of socio-ecological systems: Insights for future transdisciplinary research. Advances in Ecological Research 60: 153–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2019.03.001.

Bair, J. (2010). On difference and capital: gender and the globalization of production. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 36(1), 203–226. https://doi.org/10.1086/652912

Barclay, K. 2010. Impacts of tuna industries on coastal communities in pacific countries. Marine Policy 34: 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2009.09.003.

Barclay, K., and I. Cartwright. 2007. Capturing wealth from tuna: Case studies from the Pacific. Asia Pacific Press: ANU E Press.

Barclay, K. M., Satapornvanit, A. N., Syddall, V. M., & Williams, M. J. (2021). Tuna is women's business too: applying a gender lens to four cases in the Western and Central Pacific. Fish and Fisheries, 00(n/a), 17. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12634

Barclay, K. (2014). History of industrial tuna fishing in the pacific islands. In J. Christensen & M. Tull (Eds.), Historical Perspectives of Fisheries Exploitation in the Indo-Pacific (pp. 276). Springer Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8727-7

Bavington, D., B. Grzetic, and B. Neis. 2004. The feminist political ecology of fishing down: Reflections from Newfoundland and Labrador. Studies in Political Economy 73: 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2004.11675156.

Bott, S., Morrison, A., & Ellsberg, M. (2005). Preventing and responding to gender-based violence in middle and low-income countries: a global review and analysis.

Carpenter, R.C. 2006. Recognizing gender-based violence against civilian men and boys in conflict situations. Security Dialogue 37: 83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010606064139.

Carpenter, R. C. (2017). Recognizing gender-based violence against civilian men and boys in conflict situations. In R. Jamieson (Ed.), The Criminology of War (pp. 21). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315086859

Casey, C., R. Skibnes, and J.K. Pringle. 2011. Gender equality and corporate governance: Policy strategies in Norway and New Zealand [Article]. Gender, Work & Organization 18 (6): 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00514.x.

Chapsos, I., and S. Hamilton. 2019. Illegal fishing and fisheries crime as a transnational organized crime in Indonesia. Trends Organ Crim 22: 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-018-9329-8.

Christian, M., O. Safari, P. Ramazani, G. Burnham, and N. Glass. 2011. Sexual and gender based violence against men in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Effects on survivors, their families and the community. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 27 (4): 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2011.645144.

Cornwall, A., & Lindisfarne, N. (2006). Introduction. In A. Cornwall & N. Lindisfarne (Eds.), Dislocating masculinity: Comparative ethnographies. Routledge.

Cornwall, A., and A.-M. Rivas. 2015. From ‘gender equality and ‘women’s empowerment’ to global justice: Reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Quarterly 36 (2): 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341.

Costanza, R., R. de Groot, P. Sutton, S. van der Ploeg, S. Anderson, I. Kubiszewski, S. Farber, and R.K. Turner. 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 26: 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002.

de la Torre-Castro, M., S. Fröcklin, S. Börjesson, J. Okupnik, and N.S. Jiddawi. 2017. Gender analysis for better coastal management – increasing our understanding of social-ecological seascapes. Marine Policy 83: 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.05.015.

Delgado-Serrano, M. M., & Semerena, R. E. (2018). Gender and cross-scale differences in the perception of social-ecological systems. Sustainability, 10(9), 2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092983

DeMers, A., and V. Kahui. 2012. An overview of Fiji’s fisheries development. Marine Policy 36 (1): 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2011.05.001.

Desai, M., and R. Rinaldo. 2016. Reorienting gender and globalisation: Introduction to the special issue. Qualitative Sociology 39: 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-016-9340-9.

Evans, K., J.W. Young, S. Nicol, D. Kolody, V. Allain, J. Bell, J.N. Brown, A. Ganachaud, A.J. Hobday, B. Hunt, J. Innes, A.S. Gupta, E. van Sebille, R. Kloser, T. Patterson, and A. Singh. 2015. Optimising fisheries management in relation to tuna catches in the western central Pacific Ocean: A review of research priorities and opportunities. Marine Policy 59: 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.05.003.

Finkbeiner, E.M., N.J. Bennett, T.H. Frawley, J.G. Mason, D.K. Briscoe, C.M. Brooks, C.A. Ng, R. Ourens, K. Seto, S.S. Swanson, J. Urteaga, and L.B. Crowder. 2017. Reconstructing overfishing: Moving beyond Malthus for effective and equitable solutions. Fish and Fisheries 18 (6): 11. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12245.

Firth, S. (2000). The pacific islands and the globalisation agenda. The Contemporary Pacific, 12(1), 178–192. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23717485

Folke, C., T. Hahn, P. Olsson, and J. Norberg. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30 (1): 441–473. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511.

Fortnam, M., K. Brown, T. Chaigneau, B. Crona, T.M. Daw, D. Goncalves, C. Hicks, M. Revmatas, C. Sandbrook, and B. Schulte-Herbruggen. 2019. The gendered nature of ecosystem services. Ecological Economics 159: 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.018.

Gillet, R. (2007). A short history of industrial fishing in the Pacific Islands. http://www.fao.org/3/ai001e/ai001e00.pdf

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. International Publishers.