Abstract

Introduction

Body mass index (BMI) is a simple and cost-effective tool for monitoring the clinical responses of patients living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) after antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, especially in resource-limited settings where access to laboratory tests are limited. Current evidence on the association between longitudinal BMI variation and clinical outcomes among adults living with HIV receiving ART is essential to inform clinical guidelines. Therefore, this study examines the association between BMI variation and premature mortality in adults living with HIV on ART.

Methods

An institution-based retrospective cohort study was conducted among 834 adults living with HIV receiving ART from June 2014 to June 2020 at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in Northwest Ethiopia. We first identified predictors of mortality and BMI variation using proportional hazards regression and linear mixed models, respectively. Then, the two models were combined to form an advanced joint model to examine the effect of longitudinal BMI variation on mortality.

Results

Of the 834 participants, 49 (5.9%) died, with a mortality rate of 4.1 (95% CI 3.1, 5.4) per 100 person-years. A unit increase in BMI after ART initiation corresponded to an 18% reduction in mortality risk. Patients taking tuberculosis preventive therapy (TPT), mild clinical disease stage, and changing ART regimens were at lower risk of death. However, patients with ambulatory/bedridden functional status were at higher risk of death. Regarding BMI variation over time, patients presenting with opportunistic infections (OIs), underweight patients, patients who started a Dolutegravir (DGT)-based ART regimen, and those with severe immunodeficiency had a higher BMI increase over time. However, patients from rural areas and overweight/obese patients experienced a lower BMI increase over time.

Conclusion

BMI improvement after ART initiation was strongly associated with a lower mortality risk, regardless of BMI category. This finding implies that BMI may be used as a better predictor tool for death risk in adults living with HIV in Ethiopia. Additionally, patients who took a DGT-based ART regimen had a higher BMI increase rate over time, which aligns with possible positive effects, such as weight gain, of the DGT-based ART regimen in developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Current studies on the association between BMI variation and clinical outcomes in adults living with HIV receiving ART are essential to inform clinical guidelines. |

Therefore, this study examines the association between BMI variation and premature mortality in adults living with HIV on ART. |

This study found that an increase in BMI after ART initiation was strongly associated with a lower risk of mortality in adults living with HIV. |

Patients who took a DGT-based ART regimen had a higher BMI increase rate over time, which aligns with possible positive effects, such as weight gain, of the DGT-based ART regimen in developing countries. |

Introduction

Undernutrition [body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2] is a common problem among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]. The problem is more prominent in Ethiopia as a result of food insecurity and inadequate knowledge about healthy nutrition [2]. Approximately 26% of adults living with HIV in Ethiopia are undernourished [3] as HIV increases nutritional requirements and reduces food intake because of mouth and throat sores, loss of appetite, medication side effects, and household food insecurity. Furthermore, it decreases nutrient absorption because of HIV infection of intestinal cells, diarrhoea, and vomiting [4].

Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) significantly improves PLHIV survival, early mortality from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related illness remains high, notably in SSA [5, 6]. Common factors associated with high premature death in PLHIV are low CD4 cell counts, male gender, advanced clinical disease stage, anaemia, tuberculosis (TB), and low BMI [7,8,9,10]. Studies frequently cited that low BMI at ART initiation is an independent predictor of mortality in adults living with HIV [1, 7, 11, 12], while normal BMI is significantly associated with adequate CD4 cell count response to ART and lower risk of loss to follow-up [13].

The association between BMI and mortality in adults living with HIV is well documented, but most of these studies used baseline BMI only, which is limiting [14,15,16]. A single measurement does not adequately capture body weight variances over time, which limits association with mortality. Furthermore, the association between a single BMI measurement and mortality may be confounded by underlying diseases and health conditions that may cause weight loss [17]. Despite joint modelling being highly recommended to examine the association between time-varying covariates (i.e., BMI) and mortality, previous studies have used standard statistical models (i.e., Cox regression) to assess the association between BMI and mortality [13, 18, 19].

Viral load and CD4 cell count measurements for monitoring patient response after ART initiation are often expensive or unavailable in developing countries, including Ethiopia. Therefore, understanding and developing easy and cost-effective alternative measurements, such as BMI, are critical. Although current Ethiopian ART guidelines include BMI as a clinical indicator for patients living with HIV [20], these guidelines are not evidence informed because of lack of longitudinal studies examining the association between BMI variation and early mortality among adults living with HIV.

This study aimed to assess the impact of BMI variation on early mortality among adults living with HIV receiving ART in Northwest Ethiopia. The findings may assist healthcare professionals and policymakers design evidence-based interventions to improve BMI, eventually reducing nutrition-related mortality. Our findings can inform future Ethiopian ART guidelines.

Methods

Study Design, Period, and Area

This institution-based retrospective cohort study used de-identified data extracted from the medical records of adults living with HIV who received ART between June 2014 and June 2020 at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DMCSH) in Northwest Ethiopia. The DMCSH is located 300 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, and 265 km from Bahir-Dar, the main city of the Amhara Region. It is the only referral hospital in the East Gojjam Zone and serves more than 3.5 million people in its catchment area. The hospital has been providing HIV care and antiretroviral treatment to people living with HIV since 2005. Of the 1209 people living with HIV who received ART at DMCSH between June 2014 and June 2020, 1177 (97.4%) were 15 years of age or older (defined as adults).

Study Participants

Study participants include all adults living with HIV who received ART between June 2014 and June 2020 at DMCSH for at least 1 month and who had at least two BMI measurements. Patients who transferred to DMCSH without baseline information, were pregnant, or did not have the date of the event (death) recorded were excluded.

Sample Size and Sampling

The minimum sample size required for this study was estimated based on the formula for an independent cohort study using the Open Epi Version 3.01 [21]. The following assumptions were made: α of 5%; power of 80%; Zα/2 of 1.96; P0 of 19%; P1 of 27%; r of 1:1. The value of each parameter was obtained from a previous study conducted in Ethiopia [22], resulting in a required sample size of 802. Assuming 10% chart incompleteness, the final required sample was estimated to be 892. There were 1117 adults living with HIV on ART at DMCSH between June 2014 and June 2020. The medical records of 892 study participants were selected using a simple random sampling technique. We obtained the medical registration numbers (MRNs) for all adults living with HIV on ART at DMCSH between June 2014 and June 2020.

Data Collection Procedures

To maintain data quality, a standardized data extraction checklist was used, adapted from the national ART entry and follow-up forms currently employed by Ethiopian hospitals [20]. The data extraction checklist included sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-related variables. Sociodemographic variables were age, sex, level of education, residence, marital status, occupation, family size, and HIV-status disclosure. Clinical variables included baseline opportunistic infections (OIs), CD4 cell counts, World Health Organization (WHO) clinical disease staging, haemoglobin (Hgb) levels, nutritional status, functional status, and ART eligibility criteria. Treatment-related variables consisted of ART adherence, change in ART regimen, taking co-trimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT), taking tuberculosis preventive therapy (TPT), HIV treatment failure based on viral load, and length of time on ART. Laboratory results and measurements recorded during ART initiation were taken as baseline values. All necessary data were extracted manually from patient charts. Two epidemiologists currently working at the study hospital, both with postgraduate qualifications who are specialized in HIV care, were employed as data collectors. Additionally, a biostatistician with extensive experience in secondary data collection closely supervised the entire data collection process.

Study Variables and Measurements

This study had two outcome variables. The primary outcome was survival, determined as the length of time (in months) after ART initiation until a patient died, was lost to follow-up, transferred out to another health facility, or end of follow-up. Death was ascertained by reviewing the patient medical record written by a managing physician. Study participants were classified as event (death) or censoring (other than event). Early mortality was considered when patients died from any cause within the first 24 months of starting ART. The secondary outcome was the BMI variation in the first 2 years after ART initiation. Body weight was measured in kilograms (kg) at baseline (ART initiation) and then every 3 months for 2 years (24 months) with the corresponding BMI for each visit calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the height in metres squared (kg/m2).

Explanatory (independent) variables included sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-related variables (as described in the data collection section). Detailed information, including classification and operational definitions of the explanatory variables, was available as supplementary material (Supplementary Material).

Data Management and Statistical Analyses

Missing Data

The values for some variables were not available because of incomplete medical records. For example, 202 (24%) CD4 counts and 48 (5.7%) haemoglobin levels were not recorded in medical records. Missing values for CD4 counts and haemoglobin levels were accounted for using a multiple imputation method. Little’s missing completely at random test was applied to verify whether the values were missing at random or not before performing the actual multiple imputation [23]. A multivariate normal imputation model was employed for the final imputation. Covariates included in the imputation model were sex, residence, WHO clinical disease staging, ART adherence, nutritional status, baseline OIs, CPT, and TPT.

Longitudinal Model to Assess Variations in BMI over Time

Individual profile plots were used to assess variation in BMI within and between subjects, and a smoothed mean profile plot was used to visualize the average evolution over time. A locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) mean was used because BMI contained unbalanced data. The mean and standard deviation of BMI every 3 months were calculated. The normality assumption was assessed using a Q-Q plot, and model comparison was done using a likelihood ratio (LR) test. A linear mixed model (LMM) with random intercept and slope was used as the final model. Variables with p ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. The model goodness of fit was assessed using a model diagnostic plot.

Survival Model

The survival time of study participants was examined using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Both bivariable and multivariable proportional hazards regression models were fitted to identify predictors of mortality. Only variables with p ≤ 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable models. The proportionality assumption of the Cox-proportional hazards regression model was assessed using the Schoenfeld residual test. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values were used to assess significant predictors of mortality.

Survival and Longitudinal Joint Modelling

Association between BMI variation and early mortality was assessed using joint modelling. We compared various specifications of the baseline risk function for the survival sub-model using the Akaike information and Bayesian information criteria. Lastly, a linear mixed-effects model and a relative risk model with a piecewise-constant baseline risk function (piecewise PH-GH) were used. For all models, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16 and R version 4.1.2 statistical software.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical approvals and permissions were granted from the DMCSH Medical Director’s Office, the University of Technology Sydney Health and Medical Research Ethics Committee (ETH20-5044), and the Amhara Regional Public Health Research Ethics Review Committee (Ref. no: 816). As the study was based on existing medical records of PLHIV, obtaining participants' verbal or written informed consent was not feasible, and a waiver of consent was granted. Data were completely de-identifiable to the authors as the data abstraction tool did not include participants’ unique ART numbers and names.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Of the 892 sampled patient charts, 58 records were excluded for the following reasons: transferred to DMCSH without baseline information (n = 21), pregnant women (n = 20), weight measured only once (n = 3), the treatment outcome date was not recorded (n = 10), and height recorded only once (n = 4). In total, 834 adult records were included in the final analysis. About one-fifth (21.8%, n = 182) were from rural areas and 41.6% (n = 347) were male. The median age of participants at ART initiation was 32 years [interquartilerange (IQR): 14 years]. One quarter (25.7%; n = 214) of participants were divorced and almost one-third had no formal education (30.3%; n = 253). More than two-thirds (67.2%; n = 560) of participants disclosed their HIV status and more than half (55.2%; n = 460) came from families with fewer than three family members. See Table 1 for detailed participant sociodemographic characteristics.

Clinical and Treatment-Related Characteristics

Three hundred thirty-six (40.3%) patients presented with OIs at ART initiation with 83.1% (n = 693) classified as working functional status. One-third (33.0%; n = 275) were severely immunocompromised, and 28.3% (n = 236) were classified as having advanced disease. More than half (55.2%; n = 460) initiated ART through test and treat strategy. One-fifth (20.5%, n = 171) of participants were anaemic, with mean haemoglobin level and the median CD4 count at ART initiation being 13.8 g/dl (SD ± 2.3 g/dl) and 318.9 cell/m3 (IQR: 344 cell/m3), respectively. Most participants (87.2%; n = 727) started on the Efavirenz-based ART regimen and three-quarters (74.9%; n = 625) demonstrated good adherence to ART. About one-third (31.8%; n = 265) changed from their initial ART regimen during the study, with the availability of new drugs being the most common reason for regimen change (n = 228, 84.1%). Most patients underwent TPT and CPT with 62.8% (n = 524) and 73.6% (n = 614), respectively. ART treatment failure occurred in 23 individuals (2.7%) (see Table 2).

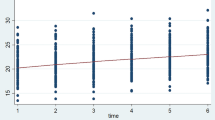

Exploratory Data Analysis of Body Mass Index Variation Over Time

At ART initiation, 223 (26.7%) participants had BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), with minimum and maximum BMI recorded during the 24 months of follow-up being 12.9 and 33.6 kg/m2, respectively. The minimum and maximum BMIs recorded during the 24 months of follow-up were 12.9 and 33.6 kg/m2, respectively. The participants' mean BMI at baseline was 20.5 kg/m2 (SD ± 3.1 kg/m2) and at termination was 22.6 kg/m2 (SD ± 3.3 kg/m2). On average, participants' mean BMI increased by 0.14 kg/m2 per month in the first 12 months and increased by 0.03 kg/m2 in the second year (see Table 3). Individual profile plots of 50 randomly selected patients showed that BMI varied significantly between individuals at ART initiation and during follow-up. However, less variability was observed within individuals (Supplementary Material). The overall smoothed mean profile plot showed a linear increase in average BMI (see Fig. 1).

Incidence of Early Mortality During ART Follow-Up

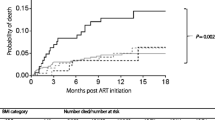

Participants were followed for a minimum of 3 months and a maximum of 24 months, contributing to 14,277 person-months. Two-year follow-up showed 49 (5.9%) participants died resulting in a mortality rate of 4.1 (95% CI 3.1, 5.4) per 100 person-years. Of these deaths, 49% (n = 24), 75.5% (n = 37), and 79.6% (n = 39) happened within the first 6, 12, and 18 months of ART follow-up, respectively. The cumulative survival probability at the end of 24 months was 0.92 (95% CI 0.89, 0.94). The mean survival time for the entire cohort was 23 months (95% CI 22.7, 23.3 months) (see Fig. 2).

Longitudinal Sub-Model

Results from the longitudinal sub-model revealed no significant difference in mean BMI between urban and rural residents at baseline; however, patients from rural areas had a lower BMI increase over time than urban patients (β = − 0.08; 95% CI: (− 0.1, − 0.02). As the ART treatment duration increased by 1 month, mean BMI increased by 0.2 kg/m2 (β = 0.2; 95% CI 0.1, 0.3). Female participants had lower mean BMI at ART initiation (β = − 0.3; 95% CI (− 0.6, − 0.1), but this difference was not statistically significant over time. Anaemic participants presented with lower mean BMI at ART initiation (β = − 0.4; 95% CI − 0.7, − 0.1), but BMI evolution over time was not significantly different, so the interaction between anaemia and time was excluded from the final model. Mean BMI of ambulatory/bedridden functional status participants was 0.9 kg/m2 lower than that of working functional status participants (β = − 0.5; 95% CI − 0.8, − 0.1) at ART initiation, although the BMI variation over time was not significantly different between groups so this interaction was excluded from the final model.

Participants who had OIs at ART initiation presented with lower mean BMI (β = − 0.3; 95% CI − 0.6, − 0.1) but had a higher rate of BMI increase (β = 0.1, 95% CI 0.03, 0.13) over time compared to non-OI-affected participants. The mean BMI difference between participants who had severe or mild immunodeficiency at baseline was not statistically significant, but increase over time was higher in participants with severe immunodeficiency than in their mildly affected counterparts (β = 0.1; 95% CI 0.07, 0.2). Those who started dolutegravir (DGT)-based ART regimen had lower mean BMI at ART initiation (β = − 1.1; 95% CI (− 1.9, − 0.5) but had a higher rate of mean BMI increase over time (β = 0.2, 95% CI 0.01, 0.4) compared to participants started other ART regimens. Patients receiving TPT had higher mean BMI than those not taking TPT at ART initiation (β = 0.5; 95% CI 0.2, 0.8) but this difference was not statistically significant during follow-up. Underweight patients presented with lower mean BMI at ART initiation (β = − 3.7; 95% CI 4.0, − 3.5) but experienced higher BMI increases over time than normal-weight patients (β = 0.1; 95% CI 0.07, 0.2). Contrarily, overweight/obese patients presented with higher mean BMI at baseline (β = 5.3; 95% CI 4.9, 5.7) but had lower BMI increase over time than normal-weight patients (β = − 0.1; 95% CI: − 0.2, − 0.03) (see Table 4).

Survival Sub-model

Significant predictors of mortality from the survival sub-model were WHO clinical disease stage, ART regimen change, taking TPT, and functional status. Participants with a mild disease stage had a 60% lower risk of death than severe disease stage individuals (AHR: 0.4; 95% CI 0.2, 0.9). Participants who changed their initial regimen had an 80% lower risk of death than participants who did not (AHR: 0.2; 95% CI 0.1, 0.5). Participants who took TPT had a 77% lower risk of death compared to participants who did not take TPT (AHR: 0.23; 95% CI 0.1, 0.5). Risk of death was 2.7 times higher in patients presenting with ambulatory/bedridden functional status as compared to those presenting with working functional status (AHR: 2.7; 95% CI 1.3, 5.4) (see Table 5).

Joint Models

The joint model showed a strong association between longitudinal BMI variation and early mortality with one unit increase in BMI corresponding to an 18% reduction in mortality risk (AHR: 0.82; 95% CI 0.75, 0.9) (see Table 5).

Discussion

This institution-based retrospective cohort study used separate models to identify mortality and BMI variation predictors in Ethiopian adults living with HIV on ART. A joint model approach examined the association between longitudinal BMI variation and early mortality. Our survival analyses identified that patients who changed their initial ART regimen, took TPT, and had mild clinical disease stage were at lower risk of death. However, patients with ambulatory/bedridden functional status were at higher risk of death. Our longitudinal sub-model also showed that patients presenting with OIs, underweight patients, patients who started a DGT-based ART regimen, and those with severe immunodeficiency had a higher BMI increase over time. However, patients from rural areas and overweight/obese patients experienced a lower BMI increase over time.

Nutritional status was not significantly associated with mortality at ART initiation. However, a unit increase in BMI corresponded to an 18% reduction in mortality risk after ART initiation. This demonstrates the time-dependent nature of BMI, which is consistent with our hypothesis. The association between BMI change and mortality was expected and consistent with previous studies [24,25,26]. This strong association could result from the recovery in adaptive and innate immunity elements after ART initiation [27]. Evidence furthermore suggests that a higher BMI is associated with higher CD4 cell counts at baseline and after 6 months [28]. The association between BMI improvement and early mortality could also reflect a negative association between BMI on OIs since OIs are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among PLHIV [29].

Our study also found that patients who took a DGT-based ART regimen had lower mean BMI at ART initiation but a higher BMI increase over time than those receiving other ART regimens. This finding is in line with a previous clinical trial conducted in developing countries [30, 31]. Although the mechanism of DGT-associated weight gain is not fully understood, it could have resulted from its higher tolerability compared to other regimens. Furthermore, patients treated with DGT were found to achieve significant viral suppression and increased CD4 counts [32]. Another possible explanation is that integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) may affect the gut microbiota of patients living with HIV [33]. Evidence suggested that a marker of gut integrity, such as fatty acid-binding protein level, is an independent predictor of weight gain and visceral fat gain in patients living with HIV [34].

In this study, patients who experienced OIs had a lower mean BMI at ART initiation but higher BMI increase over time, which aligns with previous studies [34, 35]. Higher BMI increase over time in patients with OIs could be the restoration of healthy pre-infection weight, known as the “return-to-health” phenomenon [30], reflecting effects of ART, as it significantly reduces the occurrence and recurrence of OIs and improves gastrointestinal function, appetite, and nutrient absorption [30]. Differentiating healthy from unhealthy weight gain is not easy; however, our results suggest that patients with OIs, severe immunodeficiency, and underweight had a higher BMI increase after ART initiation. This indicates that the weight gain seen in this study is more likely due to “returning to health”.

A higher rate of BMI increase was observed during follow-up in participants with severe immunodeficiency, aligning with previous research [24, 36]. Patients with severe immunodeficiency (CD4 cell counts < 200 cell/mm3) are at higher risk of developing life-threatening OIs such as oesophageal candidiasis (which compromises oral intake) [37]. As a result, the rapid weight gain in severely immunocompromised patients in our study may directly result from the beneficial effects of ART. Another reason could be that recovering from OIs can reduce metabolic demands and contribute to weight gain after starting ART. Of note, this study did not consider the time-dependent nature of CD4 cell measurements as routine CD4 cell count measurements to initiate ART were no longer required after 2016.

Patients from rural areas had a lower BMI increase over time than urban patients. A general population study also found that overweight and obesity are more prevalent in urban areas than rural areas [38], which could be due to dietary changes from a traditional diet to high-energy processed foods, fats, animal-derived foods, sugar, and sweet beverages [39]. This pattern of dietary change is more evident in urban than rural residents because of higher incomes and greater availability of processed foods [38].

This study also found a higher BMI increase over time in underweight compared to normal-weight patients. However, overweight/obese patients had a lower rate of BMI increase over time compared to normal-weight patients, which is in line with previous studies conducted in Zambia and the US [40, 41]. Underweight patients may have gained more weight because of increased food intake, reduced metabolic demand, and improved nutritional absorption after ART initiation [42]. A higher weight gain in underweight patients could also result from their desire not to look too thin, leading others to suspect their HIV status [43]. Lastly, continuous nutritional education given by health professionals as recommended by the Ethiopian ART guidelines or dietary supplements may promote healthier diets [20].

The mechanism of weight gain or loss is complex, and observational studies like ours may not address such research questions because molecular studies are needed. However, as our study suggests that patients who failed to gain weight had a higher risk of death, discussing the possible reasons for failure to gain weight in this population is essential to make recommendations. We understand possible explanations for the weight gain in our study might be speculative but are very important.

Our survival analysis found that patients with mild disease stage had a lower risk of death compared to patients with advanced disease stage, which is consistent with previous studies [44,45,46]. Patients with advanced disease stages are at higher risk of developing serious and life-threatening OIs, such as TB, cryptococcal meningitis, and toxoplasmosis [47]. Patients co-infected with TB are more likely to die in the early phase of ART because of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome [48].

Participants who took TB prophylaxis had a lower risk of death compared to participants who did not take TB prophylaxis in our study, similar to previous studies [49, 50]. This study also found that participants who changed their initial ART regimen had an 80% lower risk of death than those who did not. Due to incomplete data, we could not conclude which specific regimens are associated with lower mortality risk. The most (84%) common documented reason for regimen change in our study was the availability of new drugs. Hence, improved survival may be due to the availability of a more effective ART drug, such as DTG. However, we believe that based on the data available in our study, this would be too speculative, and further studies are needed. In response to the WHO’s recommendation, 82 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Ethiopia, reported switching to a DTG-based HIV regimen in 2019 [51].

Similar to findings of previous LMICs-based studies [16, 52,53,54,55,56], we found the risk of death among patients classified as ambulatory/bedridden functional status was much higher than those classified as working functional status. At ART initiation, bedridden functional status (i.e., remain in bed and physically inactive) patients are in an advanced disease stage and severely immunocompromised at ART initiation.

Strengths and Limitations

The large sample size (i.e., increased statistical power) and advanced statistical analyses, including missing value handling, are some of the strengths of this study. In addition, as we used longitudinal measurements of BMI, this may reflect the actual relationship between BMI (nutrition) and mortality. However, this study has some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. The values for some important nutritional status and mortality determinants, such as micronutrient deficiency, dietary diversity, and viral load, were unavailable from the routinely collected patient records. Furthermore, cause-specific mortality was not determined, as the specific causes of deaths in PLHIV were not recorded. The long-term effects of weight gain on chronic disease were not reflected in this study because of the short follow-up period (2 years). Lastly, cases of patients who died at home may not be reported to HIV clinics because of a passive reporting system, thereby potentially underestimating the mortality rate.

Conclusion

This study found that BMI improvement after ART initiation was strongly associated with lower mortality risk, regardless of BMI category. This implies that clinicians can predict patients’ prognosis (poor or good) by looking at their BMI evolution after ART initiation. Therefore, patients whose BMI does not improve after ART initiation need special attention and close follow-up because they are at higher risk of early mortality. The longitudinal finding of this study also showed that patients who took a DGT-based ART regimen had a higher BMI increase over time. This finding confirms the possible positive benefits of the DGT-based ART regimen in developing countries, such as weight gain. The study also found that patients with poor clinical conditions (i.e., presence of OIs, underweight and severe immunodeficiency) had higher BMI increase over time. Moreover, the provision of TB prophylaxis should be strengthened based on patients' eligibility. Further prospective follow-up studies are needed to examine the effects of diet, income, nutritional knowledge, exercise, and social and cultural influences on BMI improvement and their association with treatment outcomes. Lastly, the long-term effects of weight gain on chronic comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome and their association with mortality need to be investigated.

References

Alebel A, Demant D, Petrucka P, Sibbritt D. Effects of undernutrition on mortality and morbidity among adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1.

The World Bank: World Bank approves $2.3 billion program to address escalating food insecurity in Eastern and Southern Africa available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/21/world-bank-approves-2-3-billion-program-to-address-escalating-food-insecurity-in-eastern-and-southern-africa.Accessed date 10th of July 2022. In.; 2022.

Alebel A, Kibret GD, Petrucka P, Tesema C, Moges NA, Wagnew F, Asmare G, Kumera G, Bitew ZW, Ketema DB, et al. Undernutrition among Ethiopian adults living with HIV: a meta-analysis. BMC Nutr. 2020;6(1):10.

Enwereji EE, Ezeama MC, Onyemachi PE. Basic principles of nutrition, HIV and AIDS: making improvements in diet to enhance health. In: Nutrition and HIV/AIDS-Implication for Treatment, Prevention and Cure. edn.: IntechOpen London, UK; 2019.

Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG, Friedman RK, Moreira RI, Luz PM, Campos DP, Pilotto JH, Cardoso SW, Keruly JC, Moore RD. Early mortality and cause of deaths in patients using HAART in Brazil and the United States. AIDS. 2009;23(16):2107–14.

Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, Wood R, Laurent C, Sprinz E, Seyler C, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):817–24.

Zachariah R, Fitzgerald M, Massaquoi M, Pasulani O, Arnould L, Makombe S, Harries AD. Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. AIDS. 2006;20(18):2355–60.

Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT, Chandrasekhar A, Gupte N, Bisson GP, Hosseinipour M, Gummadi N. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12): e28691.

Saavedra A, Campinha-Bacote N, Hajjar M, Kenu E, Gillani FS, Obo-Akwa A, Lartey M, Kwara A. Causes of death and factors associated with early mortality of HIV-infected adults admitted to Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:48.

Leite PHAC, Coelho LE, Cardoso SW, Moreira RI, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B, Luz PM. Early mortality in a cohort of people living with HIV in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004–2015: a persisting problem. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):475.

Zhang JH, Li HL, Shi HB, Jiang HB, Hong H, Dong HJ. Survival analysis of HIV/AIDS patients with access to highly antiretroviral therapy in Ningbo during 2004–2015. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2016;37(9):1262–7.

Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, Sandvik L, Matee MI, Aglen HE, Gundersen SG, Bruun JN. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:52.

Evans D, Maskew M, Sanne I. Increased risk of mortality and loss to follow-up among HIVpositive patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis and malnutrition before antiretroviral therapy initiation: a retrospective analysis from a large urban cohort in Johannesburg, South Africa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113(3):362–72.

Tesfamariam K, Baraki N, Kedir H. Pre-ART nutritional status and its association with mortality in adult patients enrolled on ART at Fiche Hospital in North Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):512.

Dao CN, Peters PJ, Kiarie JN, Zulu I, Muiruri P, Ong’Ech J, Mutsotso W, Potter D, Njobvu L, Stringer JSA, et al. Hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypoalbuminemia predict an increased risk of mortality during the first year of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected Zambian and Kenyan women. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27(11):1149–55.

Damtew B, Mengistie B, Alemayehu T. Survival and determinants of mortality in adult HIV/Aids patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:138.

Robins JM. Causal models for estimating the effects of weight gain on mortality. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(Suppl 3):S15-41.

Otwombe KN, Petzold M, Modisenyane T, Martinson NA, Chirwa T. Factors associated with mortality in HIV-infected people in rural and urban South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1).

Naidoo K, Yende-Zuma N, Augustine S. A retrospective cohort study of body mass index and survival in HIV infected patients with and without TB co-infection. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018, 7(1).

Ministry of Health Ethiopia. National comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment training for health care providers. In. Addis Ababa: 2017.

Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD. Methods in observational epidemiology: monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics. 1996.

Teshale AB, Tsegaye AT, Wolde HF. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among adult HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital: a competing risk regression modeling. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0227473.

Little RJ. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–202.

Yuh B, Tate J, Butt AA, Crothers K, Freiberg M, Leaf D, Logeais M, Rimland D, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Ruser C, et al. Weight change after antiretroviral therapy and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(12):1852–9.

Sudfeld CR, Isanaka S, Mugusi FM, Aboud S, Wang M, Chalamilla GE, Giovannucci EL, Fawzi WW. Weight change at 1 mo of antiretroviral therapy and its association with subsequent mortality, morbidity, and CD4 T cell reconstitution in a Tanzanian HIV-infected adult cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(6):1278–87.

Madec Y, Szumilin E, Genevier C, Ferradini L, Balkan S, Pujades M, Fontanet A. Weight gain at 3 months of antiretroviral therapy is strongly associated with survival: evidence from two developing countries. AIDS. 2009;23(7):853–61.

Hughes S, Kelly P. Interactions of malnutrition and immune impairment, with specific reference to immunity against parasites. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28(11):577–88.

Bleasel JM, Heron JE, Shamu T, Chimbetete C, Dahwa R, Gracey DM. Body mass index and noninfectious comorbidity in HIV-positive patients commencing antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. HIV Med. 2020;21(10):674–9.

Alebel A, Demant D, Petrucka P, Sibbritt D. Effects of undernutrition on opportunistic infections among adults living with HIV on ART in Northwest Ethiopia: using inverse-probability weighting. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3): e0264843.

Sax PE, Erlandson KM, Lake JE, McComsey GA, Orkin C, Esser S, Brown TT, Rockstroh JK, Wei X, Carter CC, et al. Weight gain following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: risk factors in randomized comparative clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1379–89.

Thivalapill N, Simelane T, Mthethwa N, Dlamini S, Lukhele B, Okello V, Kirchner HL, Mandalakas AM, Kay AW. Transition to Dolutegravir is associated with an increase in the rate of body mass index change in a cohort of virally suppressed adolescents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(3):e580–6.

Nickel K, Halfpenny NJA, Snedecor SJ, Punekar YS. Comparative efficacy, safety and durability of dolutegravir relative to common core agents in treatment-naïve patients infected with HIV-1: an update on a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):222.

Moure R, Domingo P, Gallego-Escuredo JM, Villarroya J, Gutierrez Mdel M, Mateo MG, Domingo JC, Giralt M, Villarroya F. Impact of elvitegravir on human adipocytes: alterations in differentiation, gene expression and release of adipokines and cytokines. Antiviral Res. 2016;132:59–65.

El Kamari V, Moser C, Hileman CO, Currier JS, Brown TT, Johnston L, Hunt PW, McComsey GA. Lower pretreatment gut integrity is independently associated with fat gain on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(8):1394–401.

Alebel A, Demant D, Petrucka PM, Sibbritt D. Weight change after antiretroviral therapy initiation among adults living with HIV in Northwest Ethiopia: a longitudinal data analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2): e055266.

Tang AM, Sheehan HB, Jordan MR, Duong DV, Terrin N, Dong K, Lien TT, Trung NV, Wanke CA, Hien ND. Predictors of weight change in male HIV-positive injection drug users initiating antiretroviral therapy in Hanoi, Vietnam. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011: 890308.

Ratnam M, Nayyar AS, Reddy DS, Ruparani B, Chalapathi KV, Azmi SM. CD4 cell counts and oral manifestations in HIV infected and AIDS patients. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22(2):282.

Ajayi IO, Adebamowo C, Adami H-O, Dalal S, Diamond MB, Bajunirwe F, Guwatudde D, Njelekela M, Nankya-Mutyoba J, Chiwanga FS, et al. Urban–rural and geographic differences in overweight and obesity in four sub-Saharan African adult populations: a multi-country cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1126.

Sola AO, Steven AO, Kayode JA, Olayinka AO. Underweight, overweight and obesity in adults Nigerians living in rural and urban communities of Benue State. Ann Afr Med. 2011;10(2):139–43.

Koethe JR, Lukusa A, Giganti MJ, Chi BH, Nyirenda CK, Limbada MI, Banda Y, Stringer JS. Association between weight gain and clinical outcomes among malnourished adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(4):507–13.

Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, Headd M, Marconi V, Ganesan A, Weintrob A, Barthel RV, Fraser S, Agan BK. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4): e10106.

Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, del Rio C, Eron JJ, Gallant JE, Hoy JF, Mugavero MJ, Sax PE, Thompson MA, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2016 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2016;316(2):191–210.

Crum-Cianflone N, Tejidor R, Medina S, Barahona I, Ganesan A. Obesity among patients with HIV: the latest epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(12):925–30.

Palombi L, Marazzi MC, Guidotti G, Germano P, Buonomo E, Scarcella P, Doro Altan A, Zimba Ida V, San Lio MM, De Luca A. Incidence and predictors of death, retention, and switch to second-line regimens in antiretroviral- treated patients in sub-Saharan African sites with comprehensive monitoring availability. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):115–22.

Kouanda S, Meda IB, Nikiema L, Tiendrebeogo S, Doulougou B, Kaboré I, Sanou MJ, Greenwell F, Soudré R, Sondo B. Determinants and causes of mortality in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Burkina Faso: a five-year retrospective cohort study. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2012;24(4):478–90.

Workie KL, Birhan TY, Angaw DA. Predictors of mortality rate among adult HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy in Metema Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):27.

Melkamu MW, Gebeyehu MT, Afenigus AD, Hibstie YT, Temesgen B, Petrucka P, Alebel A. Incidence of common opportunistic infections among HIV-infected children on ART at Debre Markos referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):50.

Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):251–61.

Badje A, Moh R, Gabillard D, Guéhi C, Kabran M, Ntakpé JB, Carrou JL, Kouame GM, Ouattara E, Messou E, et al. Effect of isoniazid preventive therapy on risk of death in west African, HIV-infected adults with high CD4 cell counts: long-term follow-up of the Temprano ANRS 12136 trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(11):e1080–9.

Atey TM, Bitew H, Asgedom SW, Endrias A, Berhe DF. Does isoniazid preventive therapy provide better treatment outcomes in HIV-infected individuals in Northern Ethiopia? A retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Treat. 2020;2020:7025738.

World Health Organization. WHO recommends dolutegravir as preferred HIV treatment option in all populations available at https://www.who.int/news/item/22-07-2019-who-recommends-dolutegravir-as-preferred-hiv-treatment-option-in-all-populations. Accessed date 27 May 2022. 2019.

Biadgilign S, Reda AA, Digaffe T. Predictors of mortality among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):15.

Gesesew HA, Ward P, Woldemichael K, Mwanri L. Early mortality among children and adults in antiretroviral therapy programs in Southwest Ethiopia, 2003–15. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(6): e0198815.

Kebede A, Tessema F, Bekele G, Kura Z, Merga H. Epidemiology of survival pattern and its predictors among HIV positive patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Southern Ethiopia public health facilities: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):49.

Muhula SO, Peter M, Sibhatu B, Meshack N, Lennie K. Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of HIV-infected adult patients in urban slums of Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:63.

Bajpai R, Chaturvedi H, Jayaseelan L, Harvey P, Seguy N, Chavan L, Raj P, Pandey A. Effects of antiretroviral therapy on the survival of human immunodeficiency virus-positive adult patients in Andhra Pradesh, India: a retrospective cohort study, 2007–2013. J Prev Med Public Health. 2016;49(6):394–405.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge data collectors (Mr. Yitbarek Tenaw (MPH in Epidemiology) and Mr. Belisty Temesegen (MPH in Epidemiology)) and their supervisor (Mr. Daniel Bekele Ketema (MPH in Biostatistics). We also thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Animut Alebel: Conception of the research idea, design, analysis, interpretation, drafting and reviewing of the manuscript. David Sibbritt and Daniel Demant: Design, interpret results, review, and edit the manuscript. Pammla Petrucka: interpretation of results, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Animut Alebel, David Sibbritt, Pammla Petrucka, and Daniel Demant declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this research.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical approvals and permissions were granted from the DMCSH Medical Director’s Office, the University of Technology Sydney Health and Medical Research Ethics Committee (ETH20-5044), and the Amhara Regional Public Health Research Ethics Review Committee (ref. no: 816). As the study was based on existing medical records of PLHIV, obtaining participants' verbal or written informed consent was not feasible, and a waiver of consent was granted. Data were completely de-identifiable to the authors, as the data abstraction tool did not include participants’ unique ART numbers and names.

Data Availability

The data sets used and/or analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alebel, A., Sibbritt, D., Petrucka, P. et al. Association Between Body Mass Index Variation and Early Mortality Among 834 Ethiopian Adults Living with HIV on ART: A Joint Modelling Approach. Infect Dis Ther 12, 227–244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-022-00726-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-022-00726-5