Abstract

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a combined range of measures aimed at providing patients with cardiovascular disease with the optimum psychological and physical conditions so that they themselves can prevent their disease from progressing or potentially reversing its course. The following measures are the three main parts of CR: exercise training, lifestyle modification, and psychological intervention. The course of cardiac rehabilitation generally takes 3–4 weeks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a cost-effective, class 1a recommended part of cardiac care for patients with cardiovascular disease that generally takes 3–4 weeks to complete. |

CR has shown to improve various important patient outcomes, including exercise capacity, control of cardiovascular risk factors, quality of life, hospital readmission rates, and mortality rates. |

This review gives an overview of the current advances in CR and summarizes its benefits. |

What was learned from the study? |

The efficacy of multimodal rehabilitative interventions has been shown in several studies. |

The reduction of risk factors such as physical exercise, nicotine abstinence, weight loss, and cholesterol lowering by CR can improve quality of life and reduce mortality. |

Intensified follow-up programs improve the clinical outcome of patients with cardiac disease and should be offered whenever possible. |

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a cost-effective, class 1a recommended part of cardiac care for patients with cardiovascular disease that generally takes 3–4 weeks to complete [1, 2]. Benefits of CR have been demonstrated for patients with various cardiac diseases, such as for patients after myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass surgery, heart valve repair, percutaneous coronary interventions, stable angina, stable chronic heart failure, heart transplantation, cardiac arrhythmias, or severe arterial hypertension [2]. The goals of CR include improvement in exercise tolerance and optimization of coronary risk factors, including improvement in lipid and lipoprotein profiles, body weight, blood glucose levels, blood pressure levels, and smoking cessation. Additional attention is devoted to stress and anxiety and lessening of depression [2,3,4]. The most important targets are presented in Table 1. CR has been shown to improve various important patient outcomes, including exercise capacity, control of cardiovascular risk factors, quality of life, hospital readmission rates, and mortality rates [3,4,5].

About 10% of the statutory pension insurance budget is spent on patients with cardiovascular diseases. Most of these patients suffer from coronary heart disease (CHD) with or without myocardial infarction [6]. Older patients are more likely to suffer from acute coronary syndrome (ACS). In European registries, 27–34% of the elderly are affected by ACS [7, 8]. Coronary artery disease is closely linked to cardiovascular risk factors such as arterial hypertension, smoking, eating habits, elevated serum cholesterol, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle [9]. Besides CHD, cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation (AF), the most prevalent cardiac arrhythmia in the world today [9, 10] with about nine million patients in Europe [9], can affect a person’s capacity to work and the self-sufficiency of patients [11]. All of this also has an economic impact and CR has been shown to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease on health care.

Several efforts have been made within the field of CR in the past years. This review gives an overview of the current advances in CR and summarize its benefits. The article was written in accordance with the ethical standards given in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Effectiveness

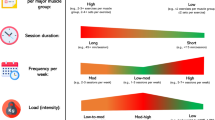

CR is a combined range of measures aimed at providing patients with chronic cardiovascular disease or following an acute incident with the optimum psychological and physical support in order that they themselves can prevent their disease from progressing or even to potentially reverse its course. The following three measures are the main part of CR: Exercise training, lifestyle modification, and psychological intervention (Fig. 1). Current data are sufficiently robust to promote strategies to improve referral to and participation in CR [12, 13]. Heran et al. analyzed 47 studies randomizing 10,794 patients to exercise-based CR or usual care. They found that exercise-based CR reduced overall and cardiovascular mortality [RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.75, 0.99) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.63, 0.87), respectively], as well as hospital admission rates [RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.51, 0.93)] [1]. Home- and clinic-based forms of CR seem to be similarly effective in regards to clinical and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients after MI, revascularization, or with heart failure [14]. Therefore, CR programs are recommended as a standard of care by major clinical guidelines [1, 2, 15].

Exercise Training

Exercise training is an important aspect during CR in patients with cardiac disease. Pollock et al. published the first recommendations for resistance exercise in CR in the year 2000 [16]. Resistance training is a form of exercise that improves muscular strength and endurance. Pollock and his team recommended that stretching or flexibility activities can begin as early as 24 h after bypass operation or 2 days after acute MI. Current guidelines recommend the careful implementation of dynamic resistance exercise, beginning with training at a low intensity (< 30%) and then an individualized progression up to 60% and sometimes up to 80% in select patients [17]. The beneficial effects of exercise training in patients with heart disease and normal left ventricular systolic function are now well known [18]. However, it has remained unclear whether this also applies to patients with heart failure (HF). Taylor et al. analyzed 44 trials with 5783 HF patients who underwent exercise CR compared with control subjects without exercise CR. Exercise CR did reduce all-cause hospitalization (RR: 0.70; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.83; TSA-adjusted CI 0.54 to 0.92) and HF-specific hospitalization (RR: 0.59; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.84; TSA-adjusted CI 0.14 for 2.46). Furthermore, patients reported improved Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire overall scores (mean difference: − 7.1; 95% CI − 10.5 to − 3.7; TSA-adjusted CI − 13.2 to − 1.0) [19]. However, further studies are needed.

In addition, in patients with AF, regular and moderate exercise training has shown positive effects [20]. CR has been proven to reduce the time in arrhythmia of patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF. In permanent AF, CR may decrease the resting ventricular response rate in patients and therefore improve symptoms related to arrhythmia. Therefore, CR seems to be a safe and manageable option for AF patients [20].

In addition to the well-established training programs, there are several new approaches. For example, Segev et al. reported on the positive effect of a stability and coordination training program for balance in the elderly with cardiovascular disease. Twenty-six patients with cardiovascular diseases (age 74 ± 8 years) were divided randomly into intervention and control groups. The intervention group received 20 min of stability and coordination exercises as part of their 80-min CR program while the control group performed the traditional CR program twice a week for 12 weeks. Balance assessment was based on three tests: the Timed Up and Go test, Functional Reach test, and Balance Error Scoring System test. In the intervention group, 70% of patients adhered to the program, with significant improvement post-intervention in the Timed Up and Go (p < 0.01) and the Balance Error Scoring System (p < 0.05) tests. In the control group, no changes were made. The authors recommended that CR centers should consider including this training alongside the routine CR program [21].

Furthermore, yoga has proven beneficial effects in several studies. Partly, it is already integrated into the standard CR program [22]. Of the seven major branches of yoga, hatha yoga is likely the most common form [23]. Patil et al. found that yoga is more effective than walking in improving cardiac function in the elderly with high pulse pressure [24]. Systolic blood pressure increases and diastolic blood pressure falls with age, leading to widening of the pulse pressure. Pulse pressure is the best tool for measuring vascular aging and a good marker for cardiovascular risk in the elderly. Elderly individuals aged ≥ 60 years with pulse pressure ≥ 60 mmHg were included in the study. The yoga group (study group, n = 30) was assigned yoga training and the walking group (exercise group, n = 30) assigned walking with loosening practices for 1 h in the morning, 6 days a week, over a period of 3 months. The pulse pressure in the yoga group was significantly lower than in the walking group [24]. Amaravathi et al. reported that yoga, in addition to conventional CR, results in higher improvements in quality of life and reduction in stress levels after 5 years after cardiac heart surgery [25]. The results of other major studies, such as the Yoga-CaRe Trial—a multicenter randomized controlled trial of 4014 patients with acute MI from India [26], are pending.

Lifestyle modification

The treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity as well as cessation of smoking is another important assignment of CR, as CR has beneficial effects on them. Mittag et al. summarized findings from a CR program and reported high pre-post effects in functional capacity (ES = 0.94), and medium-sized effects in blood pressure [27]. Excess overweight as measured by BMI is associated with an increased risk of recurrent coronary events following MI, particularly among those who are obese [28]. Jayawardena et al. report on their experience of the “plate model” as a part of dietary intervention for rehabilitation following MI. The concept of the “plate model” is a practical method to overcome the prevailing dietary pattern by reducing the average portion size of staple food in main meals, which could also ensure the sufficient intake of vegetables and protein foods simultaneously. During the 12-week follow-up period, a significant higher mean weight loss (intervention group: − 1.27 ± 3.58 kg; control group: − 0.26 ± 2.42 kg) was observed among the participants of the intervention group than the control group (P = 0.029). In addition, the intervention group showed a non-significant reduction of blood pressure and blood lipid levels [29].

However, it seems to be more difficult for patients with diabetes mellitus to achieve the goals of CR. Wallert et al. reported in their study that patients with first-time MI and diabetes are less likely to attain two of four selected CR goals compared to those without diabetes [30]. Another issue of lifestyle modification is to maintain the positive effects after the 3–4-week CR. Only 15–50% of patients attending CR still do exercise 6 months after CR, and even less after 12 months [31, 32]. Approximately 50% of patients who are smokers prior to a coronary event still smoke 6 months after the cardiac event, and less than 50% of obese patients follow dietary recommendations [33].

For this reason, there are some approaches to get the positive effect of rehabilitation. Close follow-up makes it easier to consolidate what has been learned by the patients during CR. Intensified follow-up after the CR provided positive results in the New Credo Study, a prospective, controlled, multicenter study with four cardiological rehabilitation institutions. In the first phase of this study, patients received standard CR and standard aftercare (control group). In the second phase, patients received CR based on the conditions of “New Credo” with the focus on increasing physical activity (intervention group). Data for evaluation were collected by questionnaires at three points in time. Participants reported high practicability and high satisfaction. Health- related outcomes showed a trend of positive effects in the intervention group. The intervention group shows clear advantage in regards to physical activity [34]. Similar results were provided by the intensified follow-up program IRENA (Intensivierte REhabilitationsNAchsorge) [35]. The follow-up program consists of a maximum of 24 appointments and includes medical training, gymnastics, nutritional advice and medical care.

In addition, apps and telemedicine have been increasingly used. There are some promising results [36, 37], but further studies are needed. The study by Lunde et al. included an experimental, pre-post single-arm trial lasting 12 weeks. All patients received access to an app aimed to guide individuals to change or maintain a healthy lifestyle. During the study period, patients received weekly, individualized monitoring via the app. All 14 patients included in the study used the app to promote preventive activities. Satisfaction with the technology was high, and patients found the technology-based follow-up intervention useful and motivational. Ceiling effect was present in more than 20% of the patients in several domains of the questionnaires evaluating quality of life (36-Item Short Form Health Survey and COOP/WONCA functional health assessments) and health status (EQ-5D) [36]. Johnston et al. reported on 174 ticagrelor-treated MI patients, which were randomized to an interactive patient support tool on their smartphones (active group) or a simplified tool also on their smartphones (control group). The drug adherence was significantly better in the intervention group compared with the control group [37].

Psychological intervention

Stress and anxiety are risk factors for the development of cardiac diseases [38, 39]. Past reports have shown that stress reduction and psychological intervention are associated with positive cardiac outcomes [40]. Wurst et al. report a positive effect of psychological intervention on exercise capacity. The patients who received psychological intervention were more resilient at the end of the CR than the control group. At the 12-month follow-up, the level of physical activity in the intervention group was still 94 min higher per week than in the control group (p < 0.001) [41]. Albus et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis on CR controlled trials and controlled cohort studies to evaluate the additional benefit of psychological interventions, in comparison to exercise-based CR alone, on depression and anxiety. Twenty studies with 4450 patients were analyzed; the results of this meta-analysis have shown non-significant trends for reducing depression and cardiovascular morbidity [42]. A systematic meta-analysis by Richards et al. found small to moderate improvements in anxiety, depression, and stress with additional effects on cardiovascular mortality [43] after CR. Absoli et al. observed a significant reduction of clinical psychological distress after completion of CR [44].

Gender differences

CR improves various clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease, but such programs are particularly underutilized in women [45]. In Germany, approximately 447,918 men and 211,988 women are treated in hospitals each year for coronary heart disease [46]. Approximately 67,789 men and 23,158 women were admitted to rehabilitation in 2016 with this diagnosis [47]. Härtel et al. evaluated gender differences in patients after MI during CR and thereafter in regards to their physical and mental health, the modification of cardiovascular risk factors, in health behavior, returning to work and everyday life. In this observational study, 308 male and 202 female patients after their first MI and not older than 75 years were included. The investigation included extensive medical examinations (12-channel electrogram, transthoracic echocardiography, blood sample at the beginning of CR) as well as standardized surveys (SAFE questionnaire) at different time points (beginning and end of rehabilitation, after 1.5, 3, and 10 years after being discharged home). In this study, it was shown that women, even at the beginning of CR, were significantly more physically impaired, as compared to men of the same age [48]. This was linked to the severity of the coronary heart disease, the ergometric load capacity, the number of additional non-cardiovascular diseases—such as thyroid disorders or osteoporosis—and the classic risk factors such as arterial hypertension, increased cholesterol, and obesity. Furthermore, symptoms of depression at the beginning of CR were more pronounced in women than in men [49]. During CR, risk factors can be modified successfully in male and female patients. However, women often obtain less benefit with regards to blood pressure and cholesterol levels as well as having higher anxiety and depression scores at the end of CR as compared to men [48, 49]. According to Grande et al. women feel more mentally stressed and sometimes have different expectations or personal treatment goals than men [50]. There are also differences between men and women in regards to the satisfaction with the various therapeutic measures and the subjective reasons why longer-term aftercare programs cannot be claimed [48,49,50,51]. More studies are needed to determine the different needs for individualized rehabilitation programs in men and women.

Contraindications for CR

Patients with chronic heart failure, stage IV according to WHO (World Health Organization) or cardiac arrhythmias with hemodynamic instability are not capable of CR, but these patients with CAD and/or stable chronic heart failure, regular physical training leads to an improvement in physical performance, a reduction in symptoms and thus an improvement in quality of life [1,2,3,4, 52]. Therefore, these patients should undergo a CR promptly after inpatient hemodynamic stabilization. Inpatient CR is more suitable as an outpatient CR for patients who are difficult to stabilize [52]. A contraindication can also result from the lack of motivation of the rehabilitant in terms of diagnostics and therapy. These patients should be given detailed information and motivation so that a CR is possible.

Conclusions

The efficacy of multimodal rehabilitative interventions has been shown in several studies. The reduction of risk factors such as physical exercise, nicotine abstinence, weight loss, and cholesterol lowering by CR can improve quality of life and reduce mortality. Intensified follow-up programs improve clinical outcome of patients with cardiac disease and should be offered whenever possible. In addition, CR programs have to be designed for the different needs of female and male patients. In addition, the study results of new innovations such as yoga or new apps are eagerly awaited. It remains to be seen which aspects will be permanently integrated into the CR in the future.

References

Heran BS, Chen JM, Ebrahim S, Moxham T, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD001800.

Wenger NK. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;5:1619–31.

Balady GJ, Ades PA, Bittner VA, et al. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:2951–60.

Goel K, Pack QR, Lahr B, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation is associated with reduced long-term mortality in patients undergoing combined heart valve and CABG surgery. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:159–68.

Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:571–84.

Haaf HG. Ergebnisse zur Wirksamkeit der Rehabilitation. Rehabilitation. 2005;44:e1–20.

McCune C, McKavanagh P, Menown IB. A review of current diagnosis, investigation, and management of acute coronary syndromes in elderly patients. Cardiol Ther. 2015;4:95–116.

Wienbergen H, Gitt AK, Schiele R, Juenger C, Heer T, Vogel C, et al. Different treatments and outcomes of consecutive patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction depending on initial electrocardiographic changes (results of the Acute Coronary Syndromes [ACOS] Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1543–6.

Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. New Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018–22.

Schnabel RB, Wilde S, Wild PS, Munzel T, Blankenberg S. Atrial fibrillation: its prevalence and risk factor profile in the German general population. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:293–9.

Younis Arwa, Shaviv Ella, Nof Eyal, Israel Ariel, Berkovitch Anat, Goldenberg Ilan, Glikson Michael, Klempfner Robert, Beinart Roy. The role and outcome of cardiac rehabilitation program in patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1170–6.

Wita K, Wilkosz K, Wita M, Kułach A, Wybraniec MT, Polak M, Matla M, Maciejewski K, Fluder J, Kalańska-Łukasik B, Skowerski T, Gomułka S, Turski M, Szydło K. Managed Care after Acute Myocardial Infarction (MC-AMI)—a Poland’s nationwide program of comprehensive post-MI care—improves prognosis in 12-month follow-up. Preliminary experience from a single high-volume centre. Int J Cardiol. 2019.

Oldridge N, Pakosh M, Grace SL. A systematic review of recent cardiac rehabilitation meta-analyses in patients with coronary heart disease or heart failure. Future Cardiol. 2019;15:227–49.

Taylor RS, Walker S, Ciani O, Warren F, Smart NA, Piepoli M, Davos CH. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for chronic heart failure: the EXTRAMATCH II individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23:1–98.

Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, Benson AC. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: is there an international consensus? Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2016;23:1715–33.

Pollock ML, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: an advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association; Position paper endorsed by the American College of Sports Medicine. Circulation. 2000;101:828–33.

Vanhees L, Rauch B, Piepoli M, et al. Importance of characteristics and modalities of physical activity and exercise in the management of cardiovascular health in individuals with cardiovascular disease (Part III). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:1333–56.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23: NP1–NP96.

Taylor RS, Long L, Mordi IR, Madsen MT, Davies EJ, Dalal H, Rees K, Singh SJ, Gluud C, Zwisler AD. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: Cochrane systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019.

Robaye B, Lakiss N, Dumont F, Laruelle C. Atrial fibrillation and cardiac rehabilitation: an overview. Acta Cardiol. 2019;22:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015385.2019.1565663.

Segev D, Hellerstein D, Carasso R, Dunsky A. The effect of a stability and coordination training programme on balance in older adults with cardiovascular disease: a randomised exploratory study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;21:1474515119864201.

Kaushik Chattopadhyay, Ambalam M. Chandrasekaran, Pradeep A. Praveen, Subhash C. Manchanda, Kushal Madan, Vamadevan S. Ajay, Kavita Singh, Therese Tillin, Alun D. Hughes, Nishi Chaturvedi, Shah Ebrahim, Stuart Pocock, K. Srinath Reddy, Nikhil Tandon, Dorairaj Prabhakaran, Sanjay Kinra. Development of a Yoga-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation (Yoga-CaRe) Programme for Secondary Prevention of Myocardial Infarction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019; Published online 2019 May 2. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7470184.

Papp Marian E, Lindfors Petra, Nygren-Bonnier Malin, Gullstrand Lennart, Wändell Per E. J effects of high-intensity hatha yoga on cardiovascular fitness, adipocytokines, and apolipoproteins in healthy students: a randomized controlled study. Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:81–7.

Patil SG, Patil SS, Aithala MR, Das KK. Comparison of yoga and walking-exercise on cardiac time intervals as a measure of cardiac function in elderly with increased pulse pressure. Indian Heart J. 2017;69:485–90.

Amaravathi E, Ramarao NH, Raghuram N, Pradhan B. Yoga-based postoperative cardiac rehabilitation program for improving quality of life and stress levels: fifth-year follow-up through a randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga. 2018;11:44–52.

Chandrasekaran AM, Kinra S, Ajay VS, Chattopadhyay K, Singh K, Singh K, Praveen PA, Soni D, Devarajan R, Kondal D, Manchanda SC, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N, Roberts I, Pocock S, Ebrahim S, Reddy KS, Tandon N, Yoga-CaRe Trial Team. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a Yoga-based Cardiac Rehabilitation (Yoga-CaRe) program following acute myocardial infarction: study rationale and design of a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2019;280:14–8.

Mittag O, Schramm S, Böhmen S, et al. Medium-term effects of cardiac rehabilitation in Germany: systematic review and meta-analysis of results from national and international trials. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18:587–693.

Rea TD, Heckbert SR, Kaplan RC, et al. Body mass index and the risk of recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:467–72.

Jayawardena R, Sooriyaarachchi P, Punchihewa P, Lokunarangoda N, Pathirana AK. Effects of “plate model” as a part of dietary intervention for rehabilitation following myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2019;9:179–218.

Wallert J, Mitchell A, Held C, Hagström E, Leosdottir M, Olsson EMG. Cardiac rehabilitation goal attainment after myocardial infarction with versus without diabetes: a nationwide registry study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;292:19–24.

Pinto BM, Goldstein MG, Papandonatos GD, Farrell N, Tilkemeier P, Marcus BH, Todaro JF. Maintenance of exercise after phase II cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:274–83.

Moore SM, Charvat JM, Gordon NH, Pashkow F, Ribisl P, Roberts BL, Rocco M. Effects of a CHANGE intervention to increase exercise maintenance following cardiac events. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:53–62.

Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Rydén L, Jennings C, Gyberg V, Amouyel P, Bruthans J, Castro Conde A, Cífková R, Deckers JW, De Sutter J, Dilic M, Dolzhenko M, Erglis A, Fras Z, Gaita D, Gotcheva N, Goudevenos J, Heuschmann P, Laucevicius A, Lehto S, Lovic D, Miličić D, Moore D, Nicolaides E, Oganov R, Pajak A, Pogosova N, Reiner Z, Stagmo M, Störk S, Tokgözoğlu L, Vulic D. EUROASPIRE Investigators EUROASPIRE IV: a European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:636–48.

Deck R, Beitz S, Baumbach C, Brunner S, Hoberg E, Knoglinger E. Rehab aftercare ‘new credo’ in the cardiac follow-up rehabilitation. Rehabilitation. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0899-1444.

Lamprecht J, Behrens J, Mau W, Schubert M. Intensified rehabilitation aftercare (IRENA): utilization alongside work and changes in work-related parameters. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2011;50:186–94.

Lunde P, Nilsson BB, Bergland A, Bye A. Feasibility of a mobile phone app to promote adherence to a earth-healthy lifestyle: single-arm study. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3:12679.

Johnston N, Bodegard J, Jerström S, Åkesson J, Brorsson H, Alfredsson J, Albertsson PA, Karlsson J, Varenhorst C. Effects of interactive patient smartphone support app on drug adherence and lifestyle changes in myocardial infarction patients: a randomized study. Am Heart J. 2016;178:85–94.

Chauvet-Gelinier JC, Bonin B. Stress, anxiety and depression in heart disease patients: a major challenge for cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;60(1):6–12.

Compare A, Mommersteeg PMC, Faletra F, Grossi E, Pasotti E, Moccetti T, et al. Personality traits, cardiac risk factors, and their association with presence and severity of coronary artery plaque in people with no history of cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Med. 2014;15:423–30.

Blumenthal JA, Wang JT, Babyak M, Watkins L, Kraus W, Miller P, et al. Enhancing standard cardiac rehabilitation with stress management training: background, methods, and design for the ENHANCED study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30(2):77–84.

Wurst R, Kinkel S, Lin J, Goehner W, Fuchs R. Promoting physical activity through a psychological group intervention in cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00047-y.

Albus C, Herrmann-Lingen C, Jensen K, et al. Additional effects of psychological interventions on subjective and objective outcomes compared with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation alone in patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:1035–49.

Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, et al. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease: Cochrane review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:247–59.

Gostoli S, Roncuzzi R, Urbinati S, Rafanelli C. Clinical and subclinical distress, quality of life, and psychological well-being after cardiac rehabilitation. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2017;9:349–69.

Supervía M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C, Lopez-Jimenez F, Squires RW, Pérez-Terzic CM, Brewer LC, Leth SE, Thomas RJ. Cardiac rehabilitation for women: a systematic review of barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.

Diagnosedaten der Patienten und Patientinnen in Krankenhäusern. Statistisches Bundesamt, Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.2.1, Wiesbaden 2016.

Diagnosedaten der Patienten und Patientinnen in Vorsorge- oder Rehabilitationseinrichtungen. Statistisches Bundesamt, Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.2.2, Wiesbaden 2016.

Härtel U, Gehring J, Klein G, Schraudolph M, Volger E, Klein G. Geschlechtsspezifische Unterschiede in der Rehabilitation nach erstem Myokardinfarkt. Ergebnisse der Höhenrieder Studie. Herzmedizin. 2005;22:140–50.

Härtel U. Geschlechtsspezifische Unterschiede in der kardiologischen Rehabilitation. In: Hochleitner M, editor. Gender medicine. Wien: Facultas; 2008. p. 165–82.

Grande G, Leppin A, Mannebach H, Romppel M, Altenhöner T. Geschlechtsspezifische Unterschiede in der kardiologischen. Rehabilitation. 2002;41:320–8.

Samayoa L, Grace SL, Gravely S, Scott LB, Marzolini S, Colella TJ. Sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:793–800.

Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Held K, Hoberg E, Karoff M, Rauch B. Deutsche Leitlinie zur Rehabilitation von Patienten mit Herz-Kreislauferkrankungen (DLL-KardReha). Clin Res Cardiol Suppl 2:III/1–III/54, 2007.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Barbara Bellmann participated at the Boston Scientific EP-fellowship. Andreas Rillig received travel grants from Biosense, Hansen Medical, and St. Jude Medical, and lecture fees from St. Jude Medical and Boehringer Ingelheim and participated at the Boston scientific EP-fellowship. Andreas Rillig is a member of the journal’s Editorial Board. Tina Lin received a clinical fellowship from EHRA, travel grants from Biosense Webster, St. Jude Medical, Bayer and Topera Inc, and Speakers honoraria from Servier and Boehringer. Kathrin Greissinger, Laura Rottner, and Sabine Zimmerling have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11627457.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bellmann, B., Lin, T., Greissinger, K. et al. The Beneficial Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Cardiol Ther 9, 35–44 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-020-00164-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-020-00164-9